Abstract

Large-scale genetic aberrations that underpin prostate cancer development and progression, such as copy-number alterations (CNAs), have been described but the consequences of specific changes in many identified loci is limited. Germline SNPs in the 3q26.31 locus are associated with aggressive prostate cancer, and is the location of NAALADL2, a gene overexpressed in aggressive disease. The closest gene to NAALADL2 is TBL1XR1, which is implicated in tumour development and progression. Using publicly-available cancer genomic data we report that NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains/amplifications are more prevalent in aggressive sub-types of prostate cancer when compared to primary cohorts. In primary disease, gains/amplifications occurred in 15.99% (95% CI: 13.02–18.95) and 14.96% (95% CI: 12.08–17.84%) for NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 respectively, increasing in frequency in higher Gleason grade and stage tumours. Gains/amplifications result in transcriptional changes and the development of a pro-proliferative and aggressive phenotype. These results support a pivotal role for copy-number gains in this genetic region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PCa) is the most common non-cutaneous cancer in developed countries1,2 and is defined by dynamic genome alterations and both its pathological and genetic heterogeneity3. An important pathological predictor of prostate cancer aggressiveness is Gleason grade, used to assess risk of progression and stratify patients for treatment, however, the underlying genomic changes which accompany more aggressive tumours remains incompletely defined.

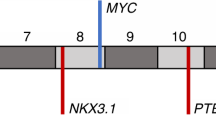

Overall copy-number alteration (CNA) burden has been linked to poorer prognosis in prostate cancer, associating with Gleason grade, biochemical recurrence and prostate cancer specific death, however the exact mechanism driving these prognostic changes is unknown and thought to be primarily driven by general chromosomal instability4,5,6. Changes in specific loci have also been linked to aggressiveness, in particular gains in proliferative genes e.g. MYC (8q24) and loss of tumour suppressors PTEN (10q23) and NKX3-1 (8p21)7,8. Many genetic alterations have been linked with prostate cancer such as point mutations in SPOP, FOXA1, and IDH19. Large-scale oncogenic structural rearrangements, translocations and copy-number changes are also common, often leading to the coordinated dysregulation of multiple elements for example the loss of 21q, which is associated with the TMPRSS:ERG fusion rearrangement and the subsequent rearrangement of SMAD410. Improved understanding of the mechanisms governing disease pathogenesis and progression may allow for better therapeutic exploitation, for example genetic alterations in the DNA repair machinery have been linked to susceptibility to PARP inhibitors in a range of tumour types and alterations in AR confer sensitivity or resistance to androgen deprivation therapy in metastatic castrate resistant prostate cancer (mCRPC)11.

NAALADL2 is located on 3q26.31 and is a member of the glutamate carboxypeptidase II family along with the widely studied PCa marker PSMA (NAALAD1)12, and its expression has previously been associated with prostate tumour stage and grade13 with expression predicting poor survival following radical prostatectomy13. A large genome-wide association study (GWAS) of 12,518 prostate cancer cases found rs78943174, a SNP within the 3q26.31 (NAALADL2) locus was associated with high Gleason sum score14. A further rs10936845 SNP was identified within a GATA2 motif that increases NAALADL2 expression in prostate cancer patients, where increased expression also predicted biochemical reccurence15. The same study showed even higher binding preference to HOXB13 and FOXA1 to this site, suggesting co-occupancy by these important transcription factors, both of which have been shown to be involved in AR cistrome reprogramming15,16.

Adjacent to NAALADL2 in the genome is TBL1XR1, a core component of nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) complex, that acts as a coregulator of nuclear receptors, influencing several cellular functions, including: growth, anti-apoptosis, and inflammation17. TBL1XR1 is also an androgen receptor (AR) co-activator18. Expression of TBL1XR1 has been associated with poor prognosis in several cancers, predicting poor overall survival and lymph node metastasis in gastric19 and ovarian cancers20 and recurrence in colorectal21, breast22 and liver cancers23.

Here we utilise large-scale publicly available genomic data to better characterise the broad somatic copy-number changes occurring within the 3q26.31-32 locus, particularly centred around gains/amplifications in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 and linking them to the clinical characteristics of aggressive prostate cancer.

Results

3q26.31-32 gain frequency is increased in aggressive PCa

Copy-number alterations often alter the expression of the gene in which they occur with gene dosage known to correlate with mRNA expression. Genetic structural variants are also known to alter transcriptional regulation by altering cis-regulatory elements such as promotors and enhancers, resulting in differential expression24,25. Increased NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 expression have previously been linked to poor prognosis in cancers leading us to examine the frequency of somatic copy-number gains in these genes across various prostate cancer subtypes19,20,21,26. Alteration frequency was assessed using data from cBioportal (Fig. 1a) and all study data was processed using a standardised pipeline to ensure comparable results. Alteration frequency was assessed in a total of 3804 patients (4029 samples) in 16 non-overlapping studies (Appendix 1); eleven studies focused on primary prostate cancer, four on metastatic prostate cancer and one on neuroendocrine and castrate-resistant cancers. Significant copy-number increases above a derived background threshold were categorised as ‘gains’ and copy-number decreases as ‘deletions’. Overall, the distribution of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 alterations were significantly different between disease sub-types to that which is expected (Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 1.19 × 10−6 and p = 2.39 × 10−6, Fig. 1a, b), with gains being most frequent in castrate-resistant prostate cancer (26.98% and 25.4% respectively), followed by neuroendocrine (20.45% and 20.45%), metastatic (5.69% and 7.58%) then primary prostate cancer (2.22% and 1.93%, Fig. 1a, b).

a NAALADL2 genetic alteration frequency (%) across different subtypes of prostate cancer. b TBL1XR1 genetic alteration frequency (%) across different subtypes of prostate cancer. P = primary prostate cancer, M = metastatic prostate cancer, NE = neuroendocrine prostate cancer and castrate resistant prostate cancer (CRPC). All annotations were assigned using Genome Nexus and CNAs are called using GISTIC or RAE algorithms. P-values show the results of a Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test to determine if the number of observed patients with each alteration type is different from that which is expected across each cancer subtype. Results detailed in Supplementary data 1.

3q26.31-32 gains extend across an oncogene-rich region of Chr3

As CNA’s are known to associate with more aggressive subtypes of prostate cancer, we investigated their association with clinical characteristics to establish if changes can be detected early in the life history of cancer, predicting more aggressive disease. We utilised copy-number data from primary organ confined disease from both the UK and Canadian International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) cohorts and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). These studies use intermediate-high risk prostate cancer patients with no treatment prior to radical prostatectomy. To allow comparisons between the studies, data were re-analysed using the Genomic Identification of Significant Targets in Cancer 2 (GISTIC2) method, favoured by the broad institute and TCGA27 as it distinguishes between low-level copy number increases (gains) and high-level copy-number increases (amplifications). Within the three cohorts, we found that copy-number gains across both genes were frequent, with gains in NAALADL2 ranging from 6.53% (Canada) to 15.63% (UK) and between 0–2.4% for amplifications (Table 1). TBL1XR1 had an almost identical CNA frequency of between 6.01% (UK) to 15.63 (Canada, Table 1).

We fitted a random-effects model to more accurately estimate the frequency of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gain/amplifications combining the data from all three cohorts, which estimated the true frequencies to be 13.06% (95% CI: 7.85–18.27%) and 12.29% (95% CI: 7.11–17.47%) for NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). Leave-one out analysis and a diagnostic plots revealed that the ICGC Canada study was a significant source of heterogeneity therefore, the study was removed and the model refit. The final estimated frequency of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains/amplifications was 15.99% (95% CI: 13.02–18.95) and 14.96% (95% CI: 12.08–17.84%) respectively in primary prostate cancer.

Due to their close proximity in the genome we investigated if gains/amplifications in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 co-occurred in the same patients using a genome-wide Fisher’s exact test with a false discovery rate correction. NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 significantly co-amplified in all three cohorts; ICGC UK p = 2.31 × 10−12, ICGC Canada p = 1.58e × 10−34 and TCGA p = 1.90 × 10−10, (Supplementary Fig. 2). Additionally, testing confirmed that wide-spanning gains/amplifications occurred in neighbouring regions in the majority of patients. In the ICGC UK cohort (n = 99), there was a significant co-occurrence of somatic copy-number gains/amplifications in NAALADL2 with TBL1XR1 (FDR-corrected Fisher’s exact test = 1.01 × 10−09, Fig. 2a). Gains in this region also significantly correlated with two regions spanning chromosomes 7 and 8, both gains previously described as being abundant in prostate cancer (Supplementary Data 2)28. The Canadian cohort (n = 389) showed a similar pattern of co-occurrence with gains/amplifications spanning the region surrounding NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 (3p25.3 to ~3q29, Fig. 2b). There was also a significant co-occurrence with gains in the beginning of chromosome 4 as well as some sporadic co-occurrence across the genome (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Data 2). These results were supported by the outcome of the same analysis in the TCGA cohort (n = 498), although several large spikes of co-occurrence were also observed in regions not local to NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1, as these spikes were not present in the other two cohorts they most likely represent artefacts (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Data 2). Overall, across the three cohorts, there were was a consistent co-amplification in region spanning 465 genes between 3p14.1 and 3q29. While a number of patients had multiple CNAs, we found no consistent co-occurrence with common CNAs such as MYC gain, FGFR1 gain, PTEN loss, RB1 loss or NKX3-1 loss (FDR-corrected Fisher’s exact test: p > 0.05).

The Y axis shows –log10 q-values from a Fishers exact test between gain/amplifications in NAALADL2 and co-occuring genes. The dotted line represents the threshold for statistical significance after correction for multiple testing. a Significantly co-occurring gains across the genome in the ICGC UK cohort. b Significantly co-occurring gains across the genome in the ICGC Canada cohort. c Significantly co-occurring gains across the genome in the TCGA cohort. NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 cytoband positions are labelled. All Fisher tests use NAALADL2 gain or amplification as the altered group. Full results are detailed in Supplementary Data 2.

The 3q26 region where NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 are located is rich in oncogenes such as PIK3CA, SOX2, ECT2 and PRKCI which may act to drive tumorigenesis29. We determined the number of known oncogenes within this defined region by comparing the 465 overlapping genes that co-amplified with NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 in all three cohorts, against the Network of Cancer Genes database30. This revealed that 67 (14.09%) of genes are known oncogenes including BCL6, ATR and PI3K family members (Supplementary Data 3). These results confirm that a high proportion of prostate cancer patients develop large copy-number gains across multiple oncogenes in this genetic region.

Gains in 3q26.31-32 associate with adverse clinical features

Common prostate cancer CNAs, such as those in MYC and PTEN, are known to associate with higher Gleason grade31. Consistent with these findings, we also found NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 amplifications were highly correlated with Grade Group (GG), showing that the frequency of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains tripling between GG1 and GG2 lesions and more than doubling between GG2 and 3 (Table 2). A Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test showed that the distribution of gains/amplifications between Grade groups was significantly different to the distribution of diploid patients for both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 (p = 7.844 × 10−08 and p = 9.179 × 10−08). When compared to common CNAs such as PTEN loss and MYC gain, the alteration frequency of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 was more correlated with higher Gleason grade groups; Spearmans rho was 0.9 (p = 0.035), 0.9 (p = 0.035) for NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 and 0.6 (p = 0.28), 0.7 (0.19) for PTEN and MYC respectively (Supplementary Fig. 3A).

Moreover, we also noted the same pattern of increasing frequency of gains with T stage (Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 0.00041 and p = 0.0028 respectively, Table 3).

Patients with gains exhibited differences in the location of the tumour within the prostate, with 57.69% and 57.14% of those with NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains having tumours in overlapping and multiple zones compared to just 42.92% and 43.24% for those without gains (Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 0.015 and p = 0.012. There was also an increased relative number of positive surgical margins (Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 0.0013 and p = 0.00059 in patients with gains (48.00% and 47.82%) compared to those without (26.93% and 27.27%). Moreover, of the 401 patients who had their lymph nodes examined, the percentage of patients with lymph node positivity defined through positivity on haematoxylin and eosin staining (H&E) was more than double in patients with NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1 gains (32.35% and 34.92%) compared to those without a gain (16.82% and 16.57%, Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 0.0032 and p = 0.00073. Finally, while only one man in the cohort had evidence of positive findings in his bone scan, we did observe a significant between the number of equivocal bone scans in patients with gains: 8.16% and 8.69% compared to 2.09% and 2.06% in those patients without gains (Chi-squared goodness-of-fit test: p = 0.011 and p = 0.0058 for NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 respectively), however, the number of expected cases in each of these categories was less than 5, adding some uncertainty to this result. We found no significant difference in the mean age between patients with different copy-numbers of NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1 (Kruskall-Wallis rank sum test: p = 0.12 and 0.23).

As gains/amplifications in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 coincide with a cluster of known oncogenes and coincide with clinical variables linked to more aggressive disease, we also compared disease-free survival. Comparing patients with gains/amplifications in NAALADL2 and TBLXR1 to those with diploid copies, we observed no significant association in the ICGC UK cohort (n = 99), although there was a trend towards reduced disease-free survival (Supplementary Fig. 4A). In the larger TCGA cohort (n = 498) there was a significant reduction in disease-free survival in patients with a gain in either NAALADL2 (Log-rank Mantel-Cox: p = 0.019) or TBL1XR1 (Log-rank Mantel-Cox: p = 0.024, Supplementary Fig. 4B).

Univariable Cox regression confirmed that carrying a gain/amplification in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 in the TCGA cohort resulted in reduction in disease-free survival, hazard ratio (HR): 1.73 (95% CI: 1.091–2.914, p = 0.021). For reference, we performed a similar analysis of patients with PTEN deletion or MYC gains, two common copy number alterations with proven association with disease-free survival in prostate cancer32,33. When patients were stratified solely by CNA status and survival compared using the Kaplan-Meier method, those patients with MYC gain or PTEN deletion (homo or hemizygous) showed no significant difference in disease-free survival (Log-rank Mantel-Cox: p = 0.11 and p = 0.077 respectively) while those stratified by NAALADL2 gain, TBL1XR1 gain or both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gain showed significant differences in survival (Log-rank Mantel-Cox: p > 0.024), Supplementary Fig. 5A–E). Univariable Cox regression estimated the hazard ratios for these copy-number alterations as: 1.415 (95% CI: 0.9256–2.163), 1.458 (95% CI: 0.9575–2.22), and 1.897 (95% CI: 1.15–3.131) for MYC, PTEN and NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 respectively. We also compared the disease-free survival of patients with only a copy-number alteration in each of the four genes where each group was mutually exclusive (Supplementary Fig. 5F, G). This showed that on the whole, patients with CNAs in NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 had reduced or equal disease-free survival as those with either only MYC gain or only PTEN loss. Patients with copy number gains in both had a worse prognosis. All clinical data is available in Supplementary Data 4.

As CNAs in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 were associated with clinical characteristics such as Gleason grade group and T stage, we used multivariable Cox regression models to confirm that any changes in survival were driven by these associations and found that copy number gains in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 were no longer significant once corrected for Gleason grade and T stage (p = 0.71184, Supplementary Data 5). These results suggest that the differences in disease-free survival seen when stratified by gain/amplification status are driven by strong association with these clinical variables.

In the ICGC cohorts, individuals with somatic single-base alterations in NAALADL2 also associated with reduced disease-free survival in a combined ICGC cohort as well as associating with reduced disease-free and overall survival in an early onset prostate cancer cohort (ICGC EOPC, Denmark). Single-base substitutions in TBL1XR1 were only associated with disease-free survival in the ICGC EOPC cohort (Supplementary Fig. 6). Single base alterations did not occur with a frequency greater than one in any single base in NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1.

3q26.31-32 gains co-occur with pro-proliferative transcription

To determine the potential functional consequences of gains within the NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 amplicon, mRNA expression profiles were explored using the TCGA RNAseq data. DESeq2 was used to determine differentially expressed genes between patients with copy-number gains for both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1, compared to those without. For NAALADL2 there were 4123 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and 4091 DEGs for TBL1XR1 when the two groups were compared (FDR < 0.05, Supplementary Data 6). Our previous study on NAALADL2 identified nine genes which were reciprocally regulated by overexpression or knockdown of NAALADL226. Of these nine we found that three (cancer antigen XAGE1B, adhesion/motiliy regulator SPON2 and AR regulator HN1) were significantly differentially expressed (p < 0.022) in patients with a NAALADL2 gain and in the same direction as the overexpression model26,34,35,36.

When comparing the DEGs between patients with and without gains/amplifications in either NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1 we observed that 77.9% of the DEGs overlapped between NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 (Fig. 3a). 48.8% (227/465) of the genes were located within the locus we identified as co-amplified with NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 and were differentially expressed, consistent with a mechanism of self-regulating expression24,25. TBL1XR1 was one of the significant overlapping DEGs, NAALADL2 was just on the boundary of statistical significance (FDR corrected Wald test: p = 0.053, Supplementary Fig. 7).

a Venn diagram showing the number and percentage of overlapping DEGs between patients with NAALADL2 gain/amplification and TBL1XR1 gain/amplification (77.9% overlap). b Venn diagram showing the number of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 DEGs and genes with identified AR binding sites (determined through ChIP-Seq and AR knockdown) and genes shown to be androgen regulated following R1881 stimulation. c Unsupervised hierarchal clustering of the top 50 most significant DEGs, bar beneath upper dendrogram shows copy-number status of patients where red is patients with a gain in both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 and grey represents those without gain/amplification in these genes. Heatmap represents mean-centred z scores derived from RKPM values. d Chord diagram showing significantly over-represented GO biological processes and key genes within these processes. All clinical data detailed in Supplementary Data.

NAALADL2 has been shown to be co-expressed with number of androgen regulated proteins and contains a number of AR binding sites and TBL1XR1 is an AR coactivator and may be involved in AR cistrome reprogramming18,26,37,38. We therefore looked at overlap between androgen regulated genes with AR binding sites (full or partial) and genes demonstrated to be androgen regulated following R1881 stimulation in at least two independent studies37,39. 50 shared genes were differentially expressed in patients with NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains/amplifications that contained AR binding sites and demonstrated androgen regulation by R1881, 506 (14.09%) genes had either a AR binding motif, were androgen regulated in two or more studies, or both (Fig. 3b).

Of the overlapping DEGs, a total of 473 (13.15%) were known oncogenes (Supplementary Data 7) which may drive an aggressive clinical phenotype. Of note was PI3K family members: PIK3C2G, PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3R4, Mucin family members: MUC1, MUC4 and MUC6 and other prostate cancer associated genes such as SMAD4, SOX9 and SPOP7,9,40,41. Additionally several genes which form commercial prognostic assays were also differentially expressed, such as the Decipher assay (NFIB, LASP1, ZWILCH, THBS2, COL1A2 and COL5A1)42, Oncotype DX assay (SFRP4, COL1A1, KLK2, TPX2)43,44 and the Prolaris assay (ASPM, BUB1B, CENPF and FOXM1)45.

We inspected of the top 50 most significant shared DEGs using unsupervised hierarchal clustering (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Data 8). DEGs mostly displayed upregulation, consistent with a gene-dosage effect (Fig. 3b)24. Enrichment for biological processes was assessed by Gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains separately, and by over-representation analysis (ORA) on the shared DEG list using WebGestalt46.

GSEA on the individual lists of DEGs showed that, despite a large overlap, the enriched biological processes did differ between the two genes; patients with a gain in NAALADL2 showed enrichment in processes related to NADH dehydrogenase complex assembly (FDR = 0.0030), mitochondrial respiratory chain complex assembly (FDR = 0.0060), translational initiation (FDR = 0.023), cytochrome complex assembly (FDR = 0.029343), protein localisation to endoplasmic reticulum (FDR = 0.035) and cytoplasmic translation (FDR = 0.037, Supplementary Data 9). Patients with a gain in TBL1XR1 showed enrichment in mitotic cell cycle phase transition, chromosome segregation, actin filament-based movement, microtubule cytoskeleton organisation involved in mitosis, regulation of cell cycle phase transition, cell cycle G1/S phase transition (FDR < 0.0001), as well as a number of other processes (Supplementary Data 9).

To understand the combined effect of gains/amplification in these genes, we investigated overrepresentation of processes in the DEGs which were common to both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1. In the shared DEG list, the significantly enriched Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes were all involved in the cell cycle cycle pathway including: mitotic regulation and chromosome segregation (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Data 10). These findings support a hypothesis whereby gains in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 concomitantly bring about mRNA expression changes which support an aggressive pro-proliferative phenotype in primary prostate cancer.

Discussion

In this study we present evidence that somatic copy-number gains in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 are more frequent in high grade and aggressive forms of prostate cancer. These results are bolstered by studies which have identified CNAs in this region in mCRPC, however, to our knowledge this is the first time these gains have been reported in neuroendocrine disease47. We also demonstrate that NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 gains occur in an earlier setting, co-occurring with gains in neighbouring genes. A major barrier to the adoption of CNA based tests in the clinic is the reliance on expensive NGS approaches as well as sufficient sequencing depth and coverage to assess overall copy-number burden. The discovery of smaller clinically significant loci could allow for cheaper, quicker targeted approaches, particularly if a single loci can elude to gains/amplifications in a larger region.

In primary prostate cancer, Gains/amplifications in this region associated with Gleason grade, tumour stage, number of positive lymph nodes, bone scan results and as these variables contribute to time to disease-free survival, patients stratified by NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 status also have altered disease-free survival times. Our work is supported by previous studies that have eluded to the clinical significance of this locus, particularly as germline SNPs within this locus have been associated with higher Gleason grade tumours and more aggressive disease14. This also supports smaller studies such as those by Heselmeyer-Haddad et al., who identified two out of seven patients with gains in TBL1XR1 in recurrent prostate cancer48. However, these studies investigated these genes in isolation, naïve to the larger context in which these alterations occur. Here we have found that gains/amplifications at this locus not only co-amplify with other described oncogenes but associate with much larger transcriptional changes which are consistent with the observed aggressive clinical phenotype.

Overall changes in copy-number burden have been shown to be indicative of genetically unstable tumours and predict prostate cancer relapse5. Many single CNAs have already been described that predict PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy including: PTEN loss, co-occurrence of PTEN, FAS (10q23.31) and PAPSS2 (10q23.2–10q23.31) loss, a loss of 16q with or without a loss of PTEN, a loss within 6q, 13q, gains in MYC, 11q13.17, 7q, and a concurrent loss of 8p22 with a gain of 8q2487,8,9,28,49. Compared to well-known CNAs such as PTEN loss and MYC amplification, we have observed that Gains/amplifications in NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 equally or better segregate patients who will have reduced disease-free survival.

The gains/amplifications in NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 also corresponded to a significant increase in both NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 mRNA, supporting previous studies that have described upregulation of these genes and linked them to poor prognosis in various cancers19,20,21,26. This suggests that gains in these genes may cause increased expression of NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 in cancers. We also noted a number of the differentially expressed genes between patients with and without a gain/amplification in NAALADL2/TBL1XR1 have been shown to be androgen regulated, however further work is required to determine if gains/amplifications in this region cause changes in AR transcriptional regulation through cis regulatory elements or as a direct consequence of the genes altered in this region18,37.

In those patients with these gains, we noted transcriptional changes in several genes associated with aggressive prostate cancer including differential expression of genes appertaining to prognostic assays such as Decipher, Oncotype DX and Prolaris, as well as families such as mucins50,51,52. This may explain the aggressive clinical phenotype observed in these patients. We also observed that when weighted individually, there were differences in enrichment of biological processes between those with NAALADL2 gains and TBL1XR1 gains suggesting that each gene results in some unique cellular changes.

Our finding that gains in the 3q26 locus result in concurrent expression of oncogenes located within this region and their downstream targets identifies multiple potential therapeutic avenues warranting further investigations. This study centred around two genes; NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1, both of which are attractive therapeutic targets with TBL1XR1 previously suggested as a potential cancer target; operating via the TGF-β signalling pathway and potentially regulating AR signalling53,54. Additionally, the tumour specificity of NAALADL2 and basal membranous localisation makes it potentially accessible using antibody-drug conjugates13. This approach may be feasible, if like other family members such as PSMA, antibody binding results in subcellular internalisation12. Moreover, several of the oncogenes in which gains co-occur, as well as the downstream oncogenes activated from gains in the 3q26 region such as: ATR, PI3K family members (PIK3C2G, PIK3CA, PIK3CB, PIK3R4), MUC4, BCL6, SOX9 can be therapeutically targeted or have been suggested as therapeutic targets in cancer51,55,56,57,58. In the PI3K pathway, PIK3CB-specific inhibitors may have utility in patients with mutations, amplifications, and/or fusion of this gene59. These findings may have clinical relevence as it has been reported by de Bono et al., that many individuals who had durable (>1 year) responses to PIK3CB-specific inhibition harboured activating mutation or amplification in PIK3CB60 and phase II trials of ipatasertib, an Akt inhibitor targeting the PI3K-Akt axis has shown promise in late stage mCRPC61. Together, our results suggest that large-scale genomic gains/amplifications occur in the 3q26 region in a high proportion of prostate cancer patients resulting in pro-tumorigenic changes which act to drive cancer aggression. Future work will be required to determine if this genetic alteration can be used to better stratify patients for therapeutics targeting activated downstream pathways.

Methods

Patient cohorts

CNA frequency in prostate cancer subtypes meta-cohort

A non-overlapping meta-cohort of all available PCa studies (accessed:10/06/2018) were assembled using the cbioportal cancer genomics portal and the alteration frequencies were plotted. A full list of all included studies can be found in supplementary methods. All somatic copy-number estimations had been determined using GISTIC2 or RAE to ensure comparability. At the time of analysis, the total cohort comprised n = 3804 patients all included studies listed in Appendix 1. Data downloaded from: https://www.cbioportal.org/.

ICGC Prostate cancer cohorts

The ICGC project was launched to coordinate large-scale cancer genome studies in tumours in 50 tumour types using fresh frozen tissue from surgically resected specimens62. For CNA analysis, the ICGC prostate cancer Prostate Adenocarcinoma United Kingdom (PRAD-UK) and Prostate Adenocarcinoma Canada (PRAD-CA) both had sufficient available data for GISTIC2 analysis (segment mean files). Some patient ID’s were also mapped to the TCGA study therefore, a non-overlapping list of patients resulted in n = 99 for ICGC UK and n = 389 for ICGC Canada. For the somatic single base alteration comparison, data was pooled from the first two cohorts and the Prostate Adenocarcinoma France (PRAD-FR) cohort (n = 566). We also performed similar analysis with the Early Onset Prostate Cancer Germany (EOPC-DE) cohort. Only single base alterations in NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1 were included in the comparison to determine reccurenc free survival following radical prostatectomy. Data downloaded on 10/06/2018 from https://dcc.icgc.org/was used for all analyses.

TCGA prostate cohort

The TCGA cohort is comprised of n = 499 primary prostate carcinomas removed by surgical resection with no prior treatment. 492 patients underwent comprehensive molecular analysis (including somatic copy-number alterations and RNAseq) using fresh frozen tissue. Samples were evaluated by multiple pathologists and cases were excluded if no tumour cells were present or RNA was significantly degraded. The average follow-up time following radical prostatectomy was just under 24 months9. The most recent version of the data (TCGA prostate adenocarcinoma, downloaded 10/06/2018) was used for all analyses and downloaded from http://firebrowse.org/?cohort=PRAD&download_dialog=true.

Statistical analysis and reproducibility

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistical analysis software or R version 3.3.1 and visualised using either R version 3.3.1 (packages: Dplyr and ggplot) or IBM SPSS statistics 24 for Windows version 22.0.

Copy-number estimation

GISTIC2 (version 6.15.28) analysis was performed in the publicly available GenePattern platform (http://genepattern.broadinstitute.org/) using the settings described by the broad institute63. Briefly, GISTIC applies both low- and high-level thresholds to gene copy levels of all patient samples. Those samples which exceed the high-level thresholds (+/−2) are classified as amplifications/deep deletions, and those which exceed the low-level thresholds (+/−1) but not the high-level thresholds are called as gain/shallow deletion. This analysis was ran using seg files containing: sample ID, chromosome name or ID, segment genomic start position, segment end position, number of probes or bins covered by the segment and the seg.mean values.

Combined estimation of copy-number frequency

In order to estimate the true frequency of gains in both genes, we employed the use of a random-effects meta-analysis model as described previously64,65. Breifly, for the three studies: ICGC UK, ICGC Canada and TCGA the number of men with a gain or amplification in either NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1 was extracted as well as the total number of patients in the cohort whom had copy-number assessed. The raw/direct proportions were calculated and we compared the the distribution of untransformed, logit and double-arcsine transformed proportions. The distributions of the proportions were assessed for normality using density plots and tested using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Untransformed proportions most resembled a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test of normality: p = 0.099) therefore, this transformation was used for the analysis. Due to significant and high inter-study variation demonstrated by a high I2 (84.13%, test for residual heterogeneity: p = 0.0019 and 84.2%, test for residual heterogeneity: p = 0.002), a random-effects model was fitted. After fitting a random-effects model to all three studies, leave-one-out analyses (LOO) and accompanying diagnostic plots were used to identify influential studies including several measures such as: externally studentized residuals, difference in fits values (DFFITS), Cook’s distances, covariance ratios, LOO estimates of the amount of heterogeneity, LOO values of the test statistics for heterogeneity, hat values and weights. In the case of the Canadian ICGC all of these measures identified it as a significant source of heterogeneity therefore it was removed and the model re-fitted. All data analysis and visualisation was performed using the R statistical environment (version 3.6.1, 2019-07-05) using the “metafor” and “meta” packages.

Co-occurrence of copy number gains/amplifications

For co-occurrence of CNAs a 2 × 2 contingency table was calculated for each gene where imputs were: the number of samples in altered in group 1 (for example, having a gain in NAALADL2), the number of samples not altered in group 1 (diploid), compared to the equivalent in group 2 (alteration in gene X) then compared using a Fisher’s exact test66. All p values were converted to q values to account for false-discovery rate and account for multiple testing (using the qvalue package). A p value of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant. From the genes identified as co-amplified with NAALADL2 and TBL1XR1, the number of oncogenes was estimated using The Network of Cancer Genes (NCG) tool30.

Clinical variable comparrisons

Chi-squared goodness-of-fit tests were used to compare frequency counts of gains/amplifications between categorical clinical groups such as Grade Group, T stage, tumour location (defined by zone), lymph node positivity and bone scan results. For Grade Group, we also assessed correlation using Spearman’s rho, pseudo-coding Grade Groups as a numeric variable and correlating to alteration frequency. All mean comparisons of continuous were carried out using a one-way ANOVA after confirming normality using Q-Q plots and histograms, if necessary variables were Log2 transformed to resemble a more normal distribution. Where results reached the threshold for significance (p = 0.05) post-hoc multiple comparisons were assessed using a Tukey test. Age in the TCGA did not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk test for normality: p = 0.0087) so a Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare age between classes of CNA.

For all Kaplan–Meier plots/survival analysis, univariable analysis was carried out using Log-Rank (Mantel-Cox) and if significant, univariable and/or multivariable Cox regression model was created which included known prognostic factors (see supplementary data). Throughout analysis, no data was excluded or imputed, any information which was not attained was left blank/missing during analysis. Kaplan–Meier estimator curves were constructed using the “survminer” R package.

All described measurements are from distinct samples and no repeated measures were used in this study.

Identification of androgen regulated DEGs

To identify DEGs that are potentially androgen regulated we identified those genes harbouring androgen response elements (ARE) from a previously described study37. Briefly, palindromic, dihexameric and complete or partial/incomplete AREs were determined by ChIP-Seq analysis. Those genes that also had altered transcriptional expression upon shRNA AR knockdown were considered AR regulated37. Here, all genes which themselves were androgen regulated and contained one or more significant motifs were compared to DEGs in patients with either NAALADL2 or TBL1XR1 gain/amplifications. Additional genes were identified from a review of a number of studies aimed at identifying AR transcriptionally regulated genes using R1881 treated LNCaPs. This produced list of genes occurring in a minimum of two independent studies39 and these two resources were compared with the identified DEGs.

Enrichment analysis

Gene set enrichment analysis and overrepresentation analysis was performed using webGEstalt (version: 0.4.3, accessed 17/05/2019)46 analyses were performed using the most recent biological processes GO annotations (GO:BP – releases/2019-03-19). For GSEA, Log2 fold changes computed using DESeq2 were used as the weighting variable. Parameters for analysis were as follows: organism of interest: Homo sapiens, Method of interest: Gene Set Enrichment Analysis or Overrepresentation analysis, Functional database: geneontology (Biological Process noRedundant), minimum number of genes for a single category was set to 5 and maximum to 2000, with up to 1000 permutations for GSEA.

Data visualisation

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistical analysis software and visualised using either R version 3.3.1 (ggplot2, heatmapper). For the enrichment analysis the most significantly altered genes between groups belonging to enriched biological functions were visualised using the “GOPlot” R package.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in the following repositories: Somatic alterations in meta-cohort from cbioportal: https://www.cbioportal.org/, ICGC cohorts: https://dcc.icgc.org/, TCGA PRAD: http://firebrowse.org/?cohort=PRAD&download_dialog=true. Full links are also provided in the materials and methods section. Data used to construct main figures are also provided as supplementary xls files. All relevant data are stored as plain text or xls files and available from the authors upon request, please contact Hayley C. Whitaker (corresponding author) at Hayley.whitaker@ucl.ac.uk.

Change history

17 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01291-8

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur. J. Cancer 49, 1374–1403 (2013).

Torre, L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. Cancer J. Clin. 2, 87–108 (2015).

Berglund, E. et al. Spatial maps of prostate cancer transcriptomes reveal an unexplored landscape of heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 9, 2419 (2018).

Williams, J. L., Greer, P. A. & Squire, J. A. Recurrent copy number alterations in prostate cancer: an in silico meta-analysis of publicly available genomic data. Cancer Genet. 207, 474–488 (2014).

Hieronymus, H. et al. Copy number alteration burden predicts prostate cancer relapse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 11139–11144 (2014).

Hieronymus, H. et al. Tumor copy number alteration burden is a pan-cancer prognostic factor associated with recurrence and death. eLife 7, e37294. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.37294 (2018).

Fraser, M. et al. Genomic hallmarks of localized, non-indolent prostate cancer. Nature 541, 359–364 (2017).

Ross-Adams, H. et al. Integration of copy number and transcriptomics provides risk stratification in prostate cancer: a discovery and validation cohort study. EBioMedicine 2, 1133–1144 (2015).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. The molecular taxonomy of primary prostate cancer. Cell 163, 1011–1025 (2015).

Baca, S. C. et al. Punctuated evolution of prostate cancer genomes. Cell 153, 666–677 (2013).

Michels, J., Vitale, I., Saparbaev, M., Castedo, M. & Kroemer, G. Predictive biomarkers for cancer therapy with PARP inhibitors. Oncogene 33, 3894–3907 (2014).

Maurer, T., Eiber, M., Schwaiger, M. & Gschwend, J. E. Current use of PSMA-PET in prostate cancer management. Nat. Rev. Urol. 13, 226–235 (2016).

Whitaker, H. C. et al. N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate peptidase-like 2 is overexpressed in cancer and promotes a pro-migratory and pro-metastatic phenotype. Oncogene 33, 5274–5287 (2014).

Berndt, S. I. et al. Two susceptibility loci identified for prostate cancer aggressiveness. Nat. Commun. 6, 6889 (2015).

Jin, H. J., Jung, S., DebRoy, A. R. & Davuluri, R. V. Identification and validation of regulatory SNPs that modulate transcription factor chromatin binding and gene expression in prostate cancer. Oncotarget 7, 54616–54626 (2016).

Pomerantz, M. M. et al. The androgen receptor cistrome is extensively reprogrammed in human prostate tumorigenesis. Nat. Genet. 47, 1346–1351 (2015).

Perissi, V., Aggarwal, A., Glass, C. K., Rose, D. W. & Rosenfeld, M. G. A corepressor/coactivator exchange complex required for transcriptional activation by nuclear receptors and other regulated transcription factors. Cell 116, 511–526 (2004).

Daniels, G. et al. TBLR1 as an androgen receptor (AR) coactivator selectively activates AR target genes to inhibit prostate cancer growth. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 21, 127–142 (2014).

Liu, F., He, Y., Cao, Q., Liu, N. & Zhang, W. TBL1XR1 is highly expressed in gastric cancer and predicts poor prognosis. Dis. Markers 2016, 2436518 (2016).

Ma, M. & Yu, N. Over-expression of TBL1XR1 indicates poor prognosis of serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 241, 239–247 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Correlations between TBL1XR1 and recurrence of colorectal cancer. Sci. Rep. 7, 44275 (2017).

Li, X. et al. Transducin (beta)-like 1 X-linked receptor 1 promotes proliferation and tumorigenicity in human breast cancer via activation of beta-catenin signaling. Breast Cancer Res. 16, 465 (2014).

Kuang, X., Zhu, J., Peng, Z., Wang, J. & Chen, Z. Transducin (Beta)-like 1 X-linked receptor 1 correlates with clinical prognosis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig. Dis. Sci. 61, 489–500 (2016).

Kahlem, P. et al. Transcript level alterations reflect gene dosage effects across multiple tissues in a mouse model of down syndrome. Genome Res. 14, 1258–1267 (2004).

Gamazon, E. R. & Stranger, B. E. The impact of human copy number variation on gene expression. Brief Funct. Genomics 14, 352–357 (2015).

Whitaker, H. C. et al. N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate peptidase-like 2 is overexpressed in cancer and promotes a pro-migratory and pro-metastatic phenotype. Oncogene 33, 5274–5287 (2014).

Mermel, C. H. et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, R41 (2011).

Taylor, B. S. et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 18, 11–22 (2010).

Fields, A. P., Justilien, V. & Murray, N. R. The chromosome 3q26 OncCassette: a multigenic driver of human cancer. Adv. Biol. Regul. 60, 47–63 (2016).

Repana, D. et al. The Network of Cancer Genes (NCG): a comprehensive catalogue of known and candidate cancer genes from cancer sequencing screens. Genome Biol. 20, 1 (2019).

Trock, B. J. et al. PTEN loss and chromosome 8 alterations in Gleason grade 3 prostate cancer cores predicts the presence of un-sampled grade 4 tumor: implications for active surveillance. Mod. Pathol. 29, 764–771 (2016).

Jamaspishvili, T. et al. Clinical implications of PTEN loss in prostate cancer. Nat. Rev. Urol. 15, 222–234 (2018).

Koh, C. M. et al. MYC and prostate cancer. Genes Cancer 1, 617–628 (2010).

Varisli, L. et al. Androgen regulated HN1 leads proteosomal degradation of androgen receptor (AR) and negatively influences AR mediated transactivation in prostate cells. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 350, 107–117 (2012).

Liao, C. H. et al. Positive regulation of spondin 2 by thyroid hormone is associated with cell migration and invasion. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 17, 99–111 (2010).

Egland, K. A., Kumar, V., Duray, P. & Pastan, I. Characterization of overlapping XAGE-1 transcripts encoding a cancer testis antigen expressed in lung, breast, and other types of cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 1, 441–450 (2002).

Wilson, S., Qi, J. & Filipp, F. V. Refinement of the androgen response element based on ChIP-Seq in androgen-insensitive and androgen-responsive prostate cancer cell lines. Sci. Rep. 6, 32611 (2016).

Testa U., Castelli G., Pelosi E. Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying prostate cancer development: therapeutic implications. Medicines. 6, 82 (2019).

Jin, H. J., Kim, J. & Yu, J. Androgen receptor genomic regulation. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2, 157–177 (2013).

Francis, J. C. et al. SOX9 is a driver of aggressive prostate cancer by promoting invasion, cell fate and cytoskeleton alterations and epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget 9, 7604–7615 (2018).

Ma, F. et al. SOX9 drives WNT pathway activation in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 1745–1758 (2016).

Karnes, R. J. et al. Validation of a genomic classifier that predicts metastasis following radical prostatectomy in an at risk patient population. J. Urol. 190, 2047–2053 (2013).

Klein, E. A. et al. A 17-gene assay to predict prostate cancer aggressiveness in the context of Gleason grade heterogeneity, tumor multifocality, and biopsy undersampling. Eur. Urol. 66, 550–560 (2014).

Knezevic, D. et al. Analytical validation of the Oncotype DX prostate cancer assay - a clinical RT-PCR assay optimized for prostate needle biopsies. BMC Genomics 14, 690 (2013).

Cuzick, J. et al. Prognostic value of a cell cycle progression signature for prostate cancer death in a conservatively managed needle biopsy cohort. Br. J. Cancer 106, 1095–1099 (2012).

Wang, J., Vasaikar, S., Shi, Z., Greer, M. & Zhang, B. WebGestalt 2017: a more comprehensive, powerful, flexible and interactive gene set enrichment analysis toolkit. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W130–W137 (2017).

Robinson, D. et al. Integrative clinical genomics of advanced prostate cancer. Cell 161, 1215–1228 (2015).

Heselmeyer-Haddad, K. M. et al. Single-cell genetic analysis reveals insights into clonal development of prostate cancers and indicates loss of PTEN as a marker of poor prognosis. Am. J. Pathol. 184, 2671–2686 (2014).

Ibeawuchi, C. et al. Exploring prostate cancer genome reveals simultaneous losses of PTEN, FAS and PAPSS2 in patients with PSA recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 16, 3856–3869 (2015).

Eminaga, O. et al. MUC1 expression by immunohistochemistry is associated with adverse pathologic features in prostate cancer: a multi-institutional study. PLoS ONE 11, e0165236 (2016).

Gautam, S. K. et al. MUC4 mucin- a therapeutic target for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 21, 657–669 (2017).

Genitsch, V., Zlobec, I., Thalmann, G. N. & Fleischmann, A. MUC1 is upregulated in advanced prostate cancer and is an independent prognostic factor. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 19, 242–247 (2016).

Li, J. Y., Daniels, G., Wang, J. & Zhang, X. TBL1XR1 in physiological and pathological states. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Urol. 3, 13–23 (2015).

Zhao, Y., Lin, H., Jiang, J., Ge, M. & Liang, X. TBL1XR1 as a potential therapeutic target that promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Exp. Ther. Med. 17, 91–98 (2019).

Rundle, S., Bradbury, A., Drew, Y., Curtin, N. J. Targeting the ATR-CHK1 axis in cancer therapy. Cancers 9, 41 (2017).

Yang, J. et al. Targeting PI3K in cancer: mechanisms and advances in clinical trials. Mol. Cancer 18, 26 (2019).

Cardenas, M. G. et al. The expanding role of the BCL6 oncoprotein as a cancer therapeutic target. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 885–893 (2017).

Garros-Regulez, L. et al. Targeting SOX2 as a therapeutic strategy in glioblastoma. Front Oncol. 6, 222 (2016).

Schwartz, S. et al. Feedback suppression of PI3Kalpha signaling in PTEN-mutated tumors is relieved by selective inhibition of PI3Kbeta. Cancer Cell 27, 109–122 (2015).

de Bono, J. et al. Abstract CT328: Exploratory genetic analysis of tumors from a phase I/II dose escalation study of GSK2636771 in patients (pts) with PTEN deficient advanced tumors. CANCER Res. 75, 15 (2015).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Randomized phase II study evaluating Akt blockade with ipatasertib, in combination with abiraterone, in patients with metastatic prostate cancer with and without PTEN loss. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 928–936 (2019).

International Cancer Genome, C. et al. International network of cancer genome projects. Nature 464, 993–998 (2010).

Center BITGDA. SNP6 Copy number analysis (GISTIC2). Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard (2016).

Wang N. How to conduct a meta-analysis of proportions in R: a comprehensive tutorial (2018).

O’Connor, E., Simpson, B. S., Houlden, H., Vandrovcova, J. & Matharu, M. Prevalence of familial cluster headache: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Headache Pain 21, 37 (2020).

Remy, E. et al. A modeling approach to explain mutually exclusive and co-occurring genetic alterations in bladder tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 75, 4042–4052 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of University College London, The University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK. Thanks to the John Black Charitable Foundation, The Urology Foundation and Rosetrees Trust for funding BS and HL. Additionally we are grateful to Prostate Cancer UK and Movember for their support via the Prostate Cancer Centre of Excellence and TLD-PF16-004 grant that supports the work in our laboratory. Finally, we are very grateful to the patients who gave their samples for this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.S. contributed study design, data and statistical analysis, generation of primary hypothesis, wrote manuscript; N.C. conducted additional genomic data analysis and provided bioinformatic expertise; H.L. provided supervision and aided in generation of primary hypothesis; H.P. provided primary data, experimental and data handling guidance, R.F. contributed primary data, genomic and bioinformtic expertise; S.H. provided experimental and biological expertise; J.P. provided primary data and proof-reading of manuscript; C.M.M. contributed supervision and clinical expertise and H.C.W. contributed supervision, aquired funding and aided in generation of primary hypothesis. All authors reviewed and proof-read the manuscript. B.S.S. takes responsibility for veracity of data in this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr Niedzica Camacho is an employee of AstraZeneca, Cambridge, UK. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, B.S., Camacho, N., Luxton, H.J. et al. Genetic alterations in the 3q26.31-32 locus confer an aggressive prostate cancer phenotype. Commun Biol 3, 440 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01175-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-020-01175-x

This article is cited by

-

The oncological relevance of fragile sites in cancer

Communications Biology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.