Abstract

Angiosperms and their insect pollinators form a foundational symbiosis, evidence for which from the Cretaceous is mostly indirect, based on fossils of insect taxa that today are anthophilous, and of fossil insects and flowers that have apparent anthophilous and entomophilous specializations, respectively. We present exceptional direct evidence preserved in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber, 100 mya, for feeding on pollen in the eudicot genus Tricolporoidites by a basal new aculeate wasp, Prosphex anthophilos, gen. et sp. nov., in the lineage that contains the ants, bees, and other stinging wasps. Plume of hundreds of pollen grains wafts from its mouth and an apparent pollen mass was detected by micro-CT in the buccal cavity: clear evidence that the wasp was foraging on the pollen. Eudicots today comprise nearly three-quarters of all angiosperm species. Prosphex feeding on Tricolporoidites supports the hypothesis that relatively small, generalized insect anthophiles were important pollinators of early angiosperms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Among symbiotic relationships unique to land, such as between fungi and plants in the forms of lichens and mycorrhizae, the pollination of angiosperms by insects has special ecological significance. Some 80–95% of the ~295,000 species of angiosperms are pollinated by insects (the proportions vary with ecosystem1,2), a species diversity that is commonly explained as a result of this symbiosis3. Besides promoting heterozygosity and sexual recombination, insect pollination confers critical ecological benefits, by allowing reproduction among distant plants. Dispersed plants can better exploit limiting resources such as light gaps, moisture, and nitrogen, and they have reduced exposure to diseases and defoliating insects that overwhelm dense monocultures4. It is likely, in fact, that insect pollination (entomophily) is the ancestral condition among angiosperms. Some gnetaleans such as Welwitschia and Gnetum, close gymnosperm relatives of angiosperms, are pollinated by assorted flies and beetles5, as are the phylogenetically basal Amborella, Nymphaeales, Illiciaceae, Trimeniaceae, and Austrobaileyales (ANITA) grade of angiosperm families6,7.

The paleontological record is gradually yielding data on the co-occurrence of insects with plant reproductive structures in geological time, providing evidence that is both direct (e.g., a fossil insect with pollen) or inferential (e.g., fossilized floral or foraging structures specialized for entomophily). The most overt insect structure specialized for anthophily is a long proboscis. In this condition the insect mouthpart appendages are extended for reaching into plant reproductive structures for feeding on nectar and pollen, having evolved multiple times among insects in various forms4. The discovery of diverse, long-tongued Mesozoic insects has revealed an unexpected array of specialized early anthophiles8. Although a long proboscis is correlated with anthophily (though not perfectly), the mouthparts in most groups of anthophilous insects in fact are not modified as such; many species are behaviorally specialized. For example, with the exception of the mostly wind-pollinated conifers, basal seed plants (including the ANITA grade of angiosperms) attract small, generalized beetles (e.g., staphylinids and scarabs), Diptera (sciaroid and culicomorphan midges; lauxaniid, ephydrid, and calliphorid flies), and short-tongued halictid bees5,6,7. Many large genera of bees, such as Andrena, Megachile, and Perdita, are morphologically generalized but oligolectic (specializing in feeding on a particular genus or family of angiosperms). Thus, the fossil record of long proboscides may greatly underestimate the extent of early anthophily.

Caution is also required when inferring an insect diet on the basis of just a long proboscis. For example, Early Cretaceous nemestrinid and tabanomorph flies with long proboscides were interpreted as angiosperm pollinators9, but a zhangsolvid fly in Early Cretaceous Spanish amber—with an even longer proboscis—had a pollen load from a gymnosperm in the Mesozoic group Benettitales10. It is possible that these Cretaceous long-tongued flies may have been feeding on early angiosperms as well, but clearly they were not restricted to them. Also, mouthpart structures presumed to be adaptations for floral feeding may well be exaptations that originally arose for other functions, even those predating the appearance of flowering plants. Species of Mesozoic scorpionflies in and related to the family Pseudopolycentropodidae, have long proboscides, apparent perfect fits for probing the narrow pollen tubes of extinct gymnosperms11. The unusual, dipterous Parapolycentropus in Burmese amber, which has a fine, stylet-like proboscis, shares adaptive features with many empidid and ceratopogonid flies that today are insectivorous, a diet typical of mecopterans12, but a specimen of this scorpionfly was recently found with nearby Cycadopites pollen13. It may have actually fed on both: some hematophagous species of mosquitoes also feed on nectar and are effective pollinators14. Pollen on or in the fossil insect provides definitive, direct evidence of diet.

In some reports on Cretaceous insects, the associated pollen was interpreted to be from possible or stem-group angiosperms, but which are actually gymnosperms. The first such reports concern pollen in the digestive tracts of lithified xyelid sawflies from the Early Cretaceous of Baissa, Siberia (Zaza Formation: Hauterivian-Barremian)15,16. Xyelidae are a small, extant Holarctic family of 82 species, the basal-most one in the Hymenoptera, whose fossil record extends to the Triassic. Larvae and adults of modern species feed extensively on the staminate cones of pines (Pinus spp.); adult mouthparts are well adapted for grazing on this and even some angiosperm pollen17. Three of the fossil sawfly species (Anthoxyela anthophaga, Spatoxyela pinicola, and Ceroxyela dolichocera) contained bisaccate and bilobed-monosaccate pollen grains from different species of conifers15,18. Spathoxyella contained pollen from the extinct gnetalean Baisanthus. Another fossil sawfly contained sulcate pollen similar to Eucommiidites (Erdtmanithecales)16, reported as Cryptosacciferites and a possible stem-group angiosperm. Even though Eucommiidites has three colpi as in angiosperms, the massive tectum and alveolate exines of pollen from the Baissa wasp indicate it is gymnosperm (the grains lack the rod-like columellae and roof-like tectum typical of angiosperms). All of these pollen species are abundant in Eurasian Cretaceous strata19,20, which, with their bisaccate structure, are features of wind-transported pollen21. Another insect–pollen relationship from the famous Baissa outcrops involves Classopolis pollen (belonging to the extinct conifer family Cheirolepidiaceae) on a lithified brachyceran fly attributed to Asilomorpha22.

Three instances of Cretaceous insects carrying pollen are in Albian-aged amber from Spain, all involving gymnosperms. One concerns a genus of thrips (order Thysanoptera: family Melanthripidae) with specialized setae apparently specialized for collecting pollen23. Some modern thrips feed on anthophyte pollen, including melanthripids; the one in Spanish amber carried pollen of Cycadopites, which is probably Cycadalean. The second case is a basal brachyceran fly in the extinct family Zhangsolvidae, Buccinatormyia magnifica, with a long, rigid proboscis, found with a clump of Exesipollenites pollen adhering to its body10. Exesipollenites is a gymnosperm probably within the extinct group Bennettitales. The third case concerns an oedemerid beetle preserved with cycad pollen on its body24.

Interestingly, another family of beetles (Boganiidae) has also been found with cycad pollen25, but in amber from the mid-Cretaceous of northern Myanmar, the most diverse Cretaceous deposit in the world and which is steadily yielding other direct insect–pollen evidence, including our present report. A general report on Burmese amber presented good photographic evidence for a permopsocid (small, stem-group relatives of living bark lice and other Psocodea), which has definitive tricolpate pollen in its gut26, but little further study or discussion of this specimen has been made.

Two reports of Cretaceous insects with pollen are difficult to evaluate. One of these was another xyelid sawfly, but in Aptian-aged limestone from the Crato Formation of Brazil27. The pollen in this xyelid was identified as Afropollis, a widespread Cretaceous genus of pollen that is spheroidal, reticulate, acolumellate, and with a loose reticulum, putatively in or close to the basal angiosperm families Winteraceae and Schizandraceae28,29. However, ultrastructural studies of its exine support Afropollis having been produced by a non-angiosperm anthophyte30. Also, this original report27 was unfortunately a meeting abstract without images or other documentation, and efforts by one of us (D.G.) to find this specimen in Brazil failed, so the identity of the pollen is impossible to confirm. The other report31 concerns a fly in Burmese amber that is a stem-group bibionid, a family that today facultatively visits flowers. Photographs of the putative pollen lack detail necessary to determine whether it is angiosperm, even though the author attributed the minute grains to two species of flowers in Burmese amber, based on overlap of the grain size and shape31.

Here we report an exceptional discovery from the Cretaceous record in which definitive angiosperm pollen is preserved with a pollen feeder and possible pollinator. It is one of just a few records of such an association where the pollen is unquestionably angiosperm, in fact belonging to a large, derived lineage of angiosperms, the eudicots. This is also the only such Cretaceous record involving a wasp in the Aculeata (stinging wasps), the major group of insect pollinators that includes the bees. As we discuss later, various aspects of aculeate structure, behavior, and biology make these insects probably the most effective insect vectors of pollen.

Results

The wasp

Family Incertae Sedis

Prosphex Grimaldi and Engel, new genus

ZooBank LSID: urn:lsid:zoobank.org:act:1F27660C-5025-479E-8C4F-F7C10600EF24

Diagnosis: A medium-sized aculeate (body length ca. 4.3 mm, excluding antennae), body compact, with scattered sparse simple setae, where evident such setae minute (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Figs. 1, 2); macropterous, with forewing venation complete and generally plesiomorphic, with 14 well-defined cells, apices of M and Cu nearly reaching wing margin (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3b); basal vein gently arched, slightly distad 1cu-a; R extending along the wing margin beyond marginal cell to the wing apex, marginal cell apex acutely rounded on the anterior wing margin; third submarginal cell broader anteriorly than posteriorly; 1m-cu entering second submarginal cell in proximal quarter; 2m-cu slightly basad 2rs-m, nearly confluent; antenna with 11 flagellomeres, antennal toruli low on face, meeting epistomal sulcus (no subantennal area); compound eyes bare; ocelli either absent (highly unusual) or small and obscure; occipital carina present, pronotal lobe lacking, posterolateral angle of pronotum angulate and extending posteriorly to meet the tegula; mesoscutal sulci reduced to parapsidal lines and incomplete mesoscutal margins, notauli apparently absent; femora not crassate (although metafemur very slightly broader than pro- and mesofemora); tibiae slender and cylindrical; tibial spur formula 1-2-2, metatibial spurs simple; metabasitibial plate absent; pretarsal claws with minute inner tooth, arolium present, and small; propodeum broad (plesiomorphically similar to chrysidoids).

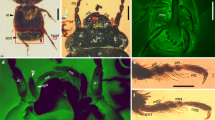

CT images and illustrations of the holotype of P. anthophilos, new genus, new species, AMNH Bu-KL18-31. a CT image, external surface. Portions of thin and/or distorted cuticle are missing, particularly in the mid-section. b, c Two CT slices through (a), showing the longitudinal (b) and dorsoventral flight muscles (c), walls of the crop (b), and a high-density mass in the buccal cavity (c), likely a pollen mass that is partially pyritized. d–h Illustrated rendering of Prosphex, showing the forewing (d, with conventional abbreviations for wing veins and cells) and the hind wing (e) (slightly reconstructed), dorsal view of head and thorax (f), left ventrolateral habitus (g: cx, coxa) and detail of sting (h). Body of the wasp is rendered as preserved, without reconstruction. All images to the same scale (scale line 1.0 mm); h is slightly magnified

Type Species: P. anthophilos Grimaldi and Engel, new species.

Etymology: Greek (masculine), pro- (first, before), and -sphex (wasp, a common suffix for aculeate wasp genera), in reference to the plesiomorphic nature and mid-Cretaceous age of the genus.

Comments: The sting, loss of cerci, and antennal structure (large scape and 11 short, stout flagellomeres) indicate that Prosphex is clearly an aculeate wasp. There are diverse aculeates belonging to ~15 living and extinct families preserved in Burmese amber32,33. Prosphex is distinctively plesiomorphic and does not belong to any of the three main lineages of aculeates as defined on the basis of their modern representatives (Chrysidoidea, Apoidea, and Vespoidea)34,35. The forewing venation is plesiomorphically nearly complete, with even the apices of forewing veins M and CuA1 virtually but not quite reaching the wing margin (Fig. 1d), unlike any living or fossil chrysidoids. Furthermore, the propodeum-metapleural suture appears to be absent, a plesiomorphic feature that would place the current fossil outside of Chrysidoidea. The lack of pronotal lobes excludes Prosphex from the Apoidea (which includes bees, sphecid, crabronid, and other wasps). The presence of 11 flagellomeres in the female excludes Prosphex from the Vespoidea or Apoidea, females of both having 10 flagellomeres (males have 11). The complete wing venation is easily derived from the earliest aculeates, such as Bethylonymidae (a possibly paraphyletic or even polyphyletic group lithified in the Late Jurassic of Kazakhstan) (Figs. 106, 107, 109, and 110 in ref. 36), but those wasps have, e.g., a strong mesoscuto-mesoscutellar sulcus in the middle of the mesosoma. Prosphex has very reduced sulci and the mesoscutellum is much smaller than the mesoscutum. Prosphex appears to be representative of a stem-group lineage that diverged prior to the divergence of the three main lineages of aculeates, although it is uncertain whether the genus could instead be a stem group to chrysidoids, sister to all Aculeata, or even sister to Euaculeata. The eventual discovery of the male and further material would greatly elucidate the phylogenetic placement of this otherwise plesiomorphic wasp.

P. anthophilos Grimaldi and Engel, new species

Diagnosis: As for genus, by monotypy.

Etymology: Greek (masculine), antho (flower or pollen), and -philos (loving), in reference to its preserved pollen meal.

Description: See Supplementary Information.

Holotype: AMNH Bu-KL18-31, from approximately the Albian–Cenomanian boundary of Kachin Province, northern Myanmar; deposited in the American Museum of Natural History, New York.

The pollen

The visible pollen load associated with the fossil wasp contains 656 mapped grains plus a mass of an indeterminate number of grains behind the right mandible and in the buccal cavity (Fig. 2a, b, j and Supplementary Figs. 1–3). This is a minimal estimate, because the number of grains in contact with the body are obscure (there are at least 30) and some were lost when the piece was originally ground and polished after excavation (some grains were exposed at the amber surface; as a result, a few are located micrometers from the surface, allowing observation with a ×100 oil-immersion objective [total ×1000 magnification] [Fig. 2c–h]). Visible grains in contact with the body occur on the right mandible, the prosternum close to the right mandible, and bases of the wings (Fig. 2a, b). Most of the pollen grains are individually scattered in plumes ventral to the body of the wasp (a few grain clusters occur), dissipating anteriorly and ventrally from their concentration near the mouthparts, the apparent source of the plumes. Most pollen grains in the plumes are badly preserved, corresponding to areas of poor preservation of the wasp, each of these grains being surrounded by a thin gas layer and sometimes deformed in the direction of the axis from the wasp. Fortunately, the pollen grains virtually in contact with the amber surface and observed at ×1000 original magnifications are finely preserved.

Angiosperm pollen load of the wasp, P. anthophilos, and pollen grain features (Tricolporoidites sp.). a Map of the preserved pollen grains in contact with (encircled) and surrounding the wasp, and microphotograph of the wasp at the same scale. Scale line 1.0 mm. The grains labeled c–h refer to those shown at high magnification in Fig. 2c−h. b Detail of the concentrated pollen mass on and around the mouthparts (drawing and microphotograph from a; at the same scale). Scale line 0.2 mm. c–e Subprolate pollen grains in equatorial view (note the colpi with poroids). f Prolate and colporoidate pollen grain in equatorial view. g, h Subprolate pollen grain in polar view showing its three colpi (same grain with different focus). Microphotographs c–h taken using a ×100 objective and at the same scale. Scale lines in c–h: 10 μm. i, j High-resolution CT scans of the wasp head (frontal view), showing just the external surface (i) and with the external surface faded to reveal the food mass in the buccal cavity (in green) (j)

The pollen grains (Fig. 2c–h) are tricolporoidate, isopolar, and tectate; the polar axis 14.28–19.00 μm long, equatorial diameter 12.38–14.28 μm, the shape subprolate to prolate (P/E 1.11–1.81), apocolpia rounded. Colpi are long, straight, nearly reaching the poles. In the equatorial area, along the colpi, a somewhat thinner exine is divided, forming small and nearly circular poroids of ~1.43 μm diameter. The exine is 1–1.5 μm thick and the surface psilate to shagrinate.

These pollen grains belong to the angiosperm form genus Tricolporoidites, erected on the basis of pollen in early Cenomanian strata of the Bohemian Basin (Czech Republic)37. This form genus was emended38 based on specimens from the late Albian of the Cheyenne and Kiowa Formations, Kansas (USA), emphasizing an isopolar pattern. Tricolporoidites pollen occurs in mid-Cretaceous amber-bearing strata from Europe39,40. The pollen preserved with the wasp greatly resembles the species Tricolporoidites subtilis Pacltová37 (1971: p. 117, pl. 9, figs. 5–9, 17), which was described from the Upper claystones of the Louny-1 bore in the Peruc Formation (Bohemian Basin). However, the type specimens are clearly smaller in size, ranging from 11 to 13 μm in the polar axis and 10 to 12 μm in equatorial diameter. T. subtilis has also been identified in the early Cenomanian of the Archingeay-Les Nouillers succession (Charentes, W France)40. The grains of Tricolporoidites sp. from Brnik (Bohemian Basin), figured but not described by Pacltová37 (1971: pl. 9, figs. 10–13), are similar in their polar orientation to those in the wasp’s pollen load.

Tricolporoidites was not reported in the short list of palynomorphs from the amber-bearing sediments in northern Myanmar41, which is not surprising, as pollen that is dispersed by wind greatly predominates in the geological strata; entomophilous pollen is generally rare. According to Ward38, the botanical affinity of Tricolporoidites corresponds to a non-magnoliid dicot, but a source family has not yet been determined. Tricolporate pollen occurs in the core eudicots (rosids and asterids, Fig. 3) and also in some basal eudicots such as Buxaceae, Sabiaceae, and Menispermaceae42; tricolporoidate pollen occurs in the core eudicots.

Summary diagram of records of insect–pollen association in the Cretaceous, showing on the left inferential/indirect evidence (features of fossil flowers or insects specialized for entomophily and anthophily, respectively) and direct evidence (an insect having pollen in or on the body). Fossil records are based on various references, many cited in the text4,11,16,23,24,26,42,55,57,64. All angiosperm records or features are depicted in yellow. Relationships among basal lineages of angiosperms are based on APG74; divergence times are arbitrary and are not intended to reflect modeled estimates

Tricolporoidites pollen is distinctive and was not produced from any of the ~15 species (in 5–6 families and 5 orders) of described or undescribed angiosperms preserved as flowers in Burmese amber32,43,44,45,46. Approximate phylogenetic positions of some of these flowers are established, such as in the Laurales and monocots47 and rosids43, but some may be improperly attributed, such as Eoëpigynia being in the Cornaceae48; its epigynous and tetramerous flowers are features found in distantly related groups such as Saxifragales, Myrtales, and Asterales49. The large size and tricolporoidate apertures also distinguish Tricolporoidites from pollen associated with the flowers of Lijinganthus revoluta, attributed to the Pentapetalae in core eudicots44; this flower genus has tricolpate pollen. Tricolpate pollen grains of the genus Nyssapollenites occur within a permopsocidan insect26 in Burmese amber and pollen of Eoëpigynia is putatively tricolpate48 but needs to be confirmed. Most of the Burmese amber flowers are unplaced and require a detailed study.

Recently, Tricolporoidites has been assigned to the eudicot angiosperms40. Tricolpate pollen, in fact, is the single defining mophological feature of the eudicots, a radiation comprising ~72% of the living species of angiosperms42.

Pollen meal

Despite compression and distortion of some portions of the wasp, especially in the propodeal region, the preservation is excellent. Computed tomography (CT) scans reveal even internal organs and tissues preserved with fidelity, the striations and positions of the dorsoventral and longitudinal flight muscles, e.g., intact and easily discerned in slice-away lateral sections, as are the walls of an apparently empty crop, which is the food storage organ (Fig. 1b, c). Three high-density areas were found inside the wasp using CT scanning (Fig. 1c). Areas of similar density were not found anywhere else in the amber. The largest high-density mass was located in the buccal cavity (Fig. 1c and Fig. 2i, j), just posterior to the mandibles, and corresponds to an area where a mass of pollen grains is partially visible behind the right mandible. Two small high-density areas are in the mesosoma, possibly within the esophagus. It is possible that these high-density areas comprised minute granules of pyrite (iron disulfide), as this mineral commonly forms in fine cracks and interstices within the amber, often infiltrating inclusions. Pyrite forms within amber, because amber-bearing sediments are typically highly reducing environments rich in sulphur and iron. However, the granularity of the high-density masses shows no cubic or otherwise geometric crystalline structure in CT scans (rather, they are rounded and amorphous Fig. 2i, j), nor does light microscopy or CT scanning reveal any fine fractures connecting these areas to the amber surface (some fine fractures occur near the wasp, but these are entirely internal, see Supplementary Fig. 2a). Another possibility is that the high-density areas are masses of pollen grains that are also nuclei for the formation of pyritic microcrystals.

Insects visit flowers for many purposes, from occasional perching and basking, to mating, an attraction to odors, adult feeding on pollen and/or nectar, floral deception and oviposition, to the gathering of pollen, nectar, essential oils or other substances for nest provisioning, or mate attraction50. Some of these, particularly the last three behaviors, are associated with insects that are obligate pollinators4. Prosphex doubtlessly was a pollen feeder. The concentration of pollen around the head and especially near the mouthparts, from which plumes of it dissipate (Fig. 2a), the mass in the buccal cavity (Fig. 2i, j), and the three areas where pollen grains adhere to the body, all indicate that the co-occurrence of the pollen and this wasp was not a chance encounter. The visible pollen grains show minimal differences in size and morphology not attributable to differential preservation (Fig. 2c–h), indicating that all are the same Tricolporoidites species, although whether it derived from a single or multiple plants is impossible to say. If additional specimens of P. anthophilos with pollen loads are discovered it would provide direct evidence as to how polylectic or flower constant this species was, much like the series of Early Cretaceous xyelid wasps with gymnosperm pollen meals16.

Discussion

A summary of the evidence for insect pollination in the Cretaceous is provided in Fig. 3, based on both direct (i.e., an insect with pollen) and indirect evidence (i.e., insect taxa that today are pollinators, and insects with conspicuous adaptive features, such as a long proboscis). The evidence for early pollination by insects is rare, mostly indirect and inferential, despite angiosperms preserved in a geological pageant of fossil leaves, stems, wood, and flowers in rocks and amber, as well as pollen that pervades sediments.

The tradeoff in the pollen fossil record is that it is much more extensive than the record of vegetative and reproductive organs, but pollen morphology is insufficient to resolve many lineages, such as among the basal grade of angiosperms with monosulcate pollen42. Tricolpate pollen appears some 25 Ma before the oldest definitive macrofossil eudicots (Fairlingtonia from the Potomac Group of Maryland, USA51, is known only from vegetative remains; it’s position as a eudicot requires further evidence42) (Fig. 3). The gap between the oldest angiosperm pollen (which is monosulcate) and macrofossil is only about 10 Ma (Fig. 3). Gaps are commonly invoked in phylogenomic models of divergence times to explain estimates of angiosperm origins deep into the Mesozoic, even the Triassic52, far preceding direct fossil evidence. A general consensus, although, is that stem-group angiosperms may have originated in the Late Jurassic 150–160 Ma, but would have been extremely scarce and ecologically insignificant42. Definitive evidence for eudicots first appears well before Prosphex was preserved in the Burmese amber, in the latest Barremian to earliest Aptian, based on palynological evidence (possibly even from the mid-Barremian, Isle of Wight53); Eudicots are well represented in the late Albian–early Cenomanian of Myanmar based on diverse floral inclusions in the amber43,44,48,54.

Prior to and including the time of Burmese amber formation 100 Ma, eight of the ten records of Cretaceous insects with pollen involve gymnosperms (Fig. 3). Moreover, these insects are phylogenetically disparate in five orders and many have structures specialized for feeding on gymnosperm cones, strobili and pollen tubes8. A striking pattern is that by the Turonian in the Late Cretaceous—exquisitely preserved as fusainized flowers from the Raritan Formation of New Jersey—there existed a suite of floral features associated with insect pollination: asymmetric and tubular corollas, clawed petals, staminodal nectaries, pollen viscin threads, dioecious flowers, nectary disks, resin glands, and staminal food bodies55. Insects probably began their intimate relationship with angiosperms when these plants debuted in the earliest Cretaceous or Late Jurassic; by 90 Ma, their relationship appears to have been consummated.

The two Cretaceous insects found with angiosperm pollen, both in Burmese amber, involve morphologically generalized insects, a permopsocid and Prosphex. Likewise, two morphologically generalized, stem-group species also in Burmese amber apparently belong to groups that today are major pollinators: the putative bee Melittosphex56 and the flower fly Prosyrphus57. Melittosphex is problematic, because its hairs are barely plumose, it lacks the pronotal lobes typical of apoids, and it has a broad pronotum, like chrysidoids. Burmese amber has been especially revealing, because it was formed and preserved in massive quantities;32 it will no doubt be yielding much further pollen–insect evidence.

Three main factors contribute to the effectiveness of aculeate wasps as pollinators, which apparently pre-adapted bees to become the predominant pollinators, one being the strong, directed flight of the larger species, particularly ones in the Apoidea and Vespoidea. Another is intelligence. All insects undoubtedly are capable of avoidance learning, but longer-lived species that are active foragers, such as aculeates, are adept at associative learning. Honey-bee foragers, for instance, learn and communicate to hive members the direction, distance, and quality of nectar sources, among various other tasks58. Even though sociality is usually associated with keen learning ability, species of solitary, ground-nesting bees, and other wasps, e.g., visually imprint their nest location on a learning flight59. Learning allows an individual to specialize as conditions allow; in pollinators, it promotes foraging fidelity and flower constancy60. Such intelligence has a neurological basis in an area of the insect brain called the mushroom bodies, which function in the processing of olfactory, gustatory, visual, and tactile information, and associative learning. Mushroom bodies are highly developed in apocritan wasps61.

Lastly, the aculeate sting allows wasps to forage exposed on flowers with relative impunity, testament to which are the hundreds of flower-visiting syrphid and conopid flies, beetles, and diurnal moth species that mimic the bold black-and-yellow aposematic color patterns of vespids and bees. Basal lineages of Vespidae existed by the time Burmese amber was formed in the mid-Cretaceous62,63 and a species of zhangsolvid fly even exists in Burmese amber with vespid-like aposematic patterns64. For Prosphex, its body coloration was either uniform or the patterns were not preserved, which is typical of inclusions in amber, the zhangsolvid being a rare exception.

The main radiation of aculeate wasps preceded that of angiosperms by about 30 million years. The oldest direct (fossil) evidence of aculeates is the apparent stem-group family Bethylonymidae, from the Upper Jurassic of Kazakhstan36. By the Early Cretaceous, 140–135 Ma, several extinct and extant families of aculeates existed, with the main radiation of families occurring some 150–135 Ma4. By the time of the main period of angiosperm radiation, some 120–90 Ma, aculeate wasps were well evolved.

Burmese amber was formed in a dense, megathermal conifer forest at or near the paleoequator, in a wet paleoclimate with organisms typical of modern tropical rain forests: velvet worms (Onycophora), diverse ants, and termites, even dicot leaves with well-developed drip tips32. In the understory were diverse herbaceous and shrubby angiosperms, the type of biological community that basal, ANITA-grade angiosperms largely inhabit today65. If the early angiosperms were scattered and localized throughout the forest, growing in light gaps and littoral areas edging streams and ponds65, they would have required efficient, reliable, and competitive pollen vectors, such as aculeate wasps. Despite the diversity of long-tongued insects in the Early Cretaceous, many of these may actually have been gymnosperm pollinators that did not transition to the pollination of angiosperms. The hypothesis that early angiosperms were visited by myriad small, generalized insects4,66 is gathering new supportive evidence. Lastly, the sum of evidence is compelling for entomophily being the ancestral reproductive mode in angiosperms, which may explain a major gap in the pollen fossil record, particularly for the eudicots42 (Fig. 3). The rarity of pollen in the Valanginian has traditionally been attributed to the rarity and dispersion of early angiosperms; however, as entomophilous pollen is far less common in geological sediments, it would further obscure the earliest traces of angiosperms.

Methods

The amber

Burmese amber derives from the middle of the Cretaceous, approximately near the boundary between the Early and Late Cretaceous (Albian–Cenomanian stages, Fig. 3), ca. 100 million years old based on U-Pb isotope dating67. It is the largest and most diverse Cretaceous deposit in the world and is marketed commercially worldwide. The piece of amber studied here, AMNH Bu-KL18-31, was among several hundred pieces that were acquired by the AMNH from Burmese amber dealers. The source of the amber is from outcrops in Kachin Province, northern Myanmar32. Similar to most marketed Burmese amber, the piece was a polished cabochen; subsequently, two flat, opposing surfaces were trimmed, ground, and polished on each side of the wasp and pollen plume, to obtain close views of the insect and pollen inclusions (a water-fed diamond-edged trim saw and Buehler Ecomet lapidary wheel were used). The piece was not embedded in synthetic resin in order to minimize thickness for high-magnification work and to optimize CT scan imaging, but it will be embedded in EpoTek 301-2 to preserve the amber against long-term degradation.

Palynological analysis

Two pollen grains close to the surface of the amber were imaged at the AMNH with a Zeiss LSM710 (AxioObserver) confocal laser-scanning microscope using a Plan-Apochromat ×20/0.8 M27 objective. Fluorescence images (both single and Z-stacks) were taken at an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and an emission wavelength of 621 nm, but resolution was insufficient and background fluorescence too bright for useful images, so the pollen grains were studied at the Museo Geominero in Madrid by wide-field transmitted light microscopy, using an Olympus BX51microscope. Photomicrographs were made with a Color View IIIu digital camera attached to the microscope. Morphology of the studied grains were described using established terminology68,69. Pollen grains were mapped by hand using a camera lucida attached to an Olympus BX41 microscope. The habitus of the wasp showing the pollen load was photographed using a Canon EOS 650D camera with Macrofotografía software, version 1.1.0.5.

CT imaging

The amber piece was examined using X-Ray micro-CT at the American Museum of Natural History Microscopy and Imaging Facility, with a GE Phoenix v/tome/x s240 and 180 kV source. An initial scan at 70 kV and 220 μA with 500 ms exposures established baseline parameters and determined approximate internal preservation of the wasp. A total of 1800 images were taken; for each image 6 exposures were used, from which one was skipped and 5 averaged. The specimen was scanned a second time at greater resolution and significantly longer duration. The cuticle of insects in amber occasionally have X-ray absorption values close to that of the amber itself. Longer scans at lower energies can help achieve greater dynamic range, better differentiating internal and external morphology, but this varies greatly with, e.g., inclusion preservation and composition of the amber (e.g., Fig. 1a). As with the first scan, 1800 images were taken, but at lower beam energy and current (60 kV, 200 μA). Exposures were 1000 ms and as with the first scan each image used six exposures with a skip of 1 and average of 5. Three vertically stacked scans were used to reach a smaller final voxel size of approximately 2.8 μm3.

Volume reconstruction from raw projections used GE Phoenix datos/x 2.3.2. A combination of manual and semi-automatic geometry correction was used and reconstructed volumes were exported as 16 bit TIFF stacks for post-processing. Three sections comprising the second scan were manually combined using Fiji/ImageJ 2.0.070,71 and 3D Stitching72. Volume datasets were exported in NRRD format before segmentation and rendering. Post-processing and isolation of regions of interest via segmentation used the open-source project 3D Slicer (www.slicer.org)73. As the Slicer project is under continuous development, various nightly builds were used, spanning versions 4.7 through 4.11. Segmentation was done with the Segment Editor module, primarily using a combination of thresholding and hand selection of areas of interest. Visualizations were rendered using either 3D Slicer or Blender 2.78c (Blender Foundation) with the Cycles render engine. Differences between a high-density mass in the buccal cavity and the surrounding region were studied by isolating the head capsule as a separate volume dataset, for plotting an intensity histogram. Segmentation used thresholding and was rendered using transparent shaders to illustrate the size, granularity, and location inside the mouthparts.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

CT scan raw files are deposited in and available publicly at https://datadryad.org/stash/share/sSWP3uN9c_08EoYeozfnL_e2usagyA9RhW6FlhQtA-w. The holotype specimen of P. anthophilos is housed at the American Museum of Natural History (Division of Invertebrate Zoology), its collections of which are available for study to qualified researchers.

References

Kress, W. J., & Beach, J. H. in La Selva: ecology and natural history of a neotropical rain forest (eds L. A. McDade, K. S. Bawa, H. A. Hespenheide, and G. S. Hartshorn) pp 161−182, 486 (Univ. Chicago Press, 1994).

Momose, K. et al. Pollination biology in a lowland dipterocarp forest in Sarawak, Malaysia. I. Characteristics of the plant‐pollinator community in a lowland dipterocarp forest. Am. J. Bot. 85, 1477–1501 (1998).

Crepet, W. L. & Niklas, K. J. Darwin’s second “abominable mystery”: why are there so many angiosperm species? Am. J. Bot. 96, 366–381 (2009).

Grimaldi, D. A. & Engel, M. S. Evolution of the Insects (Cambridge Univ. Press, New York/Cambridge, 2005).

Kato, M., Inoue, T. & Nagamitsu, T. Pollination biology of Gnetum (Gnetaceae) in a lowland mixed dipterocarp forest in Sarawak. Am. J. Bot. 82, 862–868 (1995).

Thien, L. B. et al. Pollination biology of basal angiosperms (ANITA grade). Am. J. Bot. 96, 166–182 (2009).

Luo, S. X. et al. The largest early-diverging angiosperm family is mostly pollinated by ovipositing insects and so are most surviving lineages of early angiosperms. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 285, 20172365 (2018).

Labandeira, C. C. The pollination of mid-Mesozoic seed plants and the early history of long-proboscid insects. Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 97, 469–514 (2010).

Ren, D. Flower-associated Brachycera flies as fossil evidence for Jurassic angiosperm origins. Science 280, 85–88 (1998).

Peñalver, E. et al. Long-proboscid flies as pollinators of Cretaceous gymnosperms. Curr. Biol. 25, 1917–1923 (2015).

Ren, D. et al. A probable pollination mode before angiosperms: Eurasian, long-proboscid scorpionflies. Science 326, 840–847 (2009).

Grimaldi, D. & Johnston, M. A. The long-tongued Cretaceous scorpionfly Parapolycentropus Grimaldi and Rasnitsyn (Mecoptera: Pseudopolycentropodidae): new data and interpretations. Am. Mus. Novit. 3793, 1–25 (2014).

Lin, X., Labandeira, C. C., Shih, C., Hotton, C. L. & Ren, D. Life habits and evolutionary biology of new two-winged long-proboscis scorpionflies from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber. Nat. Commun. 10, 1235 (2019).

Larson, B. M. H., Kevan, P. G. & Inouye, D. W. Flies and flowers: Taxonomic diversity of anthophiles and pollinators. Can. Entom. 133, 439–465 (2001).

Krassilov, V. A. & Rasnitsyn, A. P. A unique find: pollen in the intestine of Early Cretaceous sawflies. Paleontol. J. 4, 80–95 (1982).

Krassilov, V., Tekleva, M., Meyer-Melikyan, N. & Rasnitsyn, A. New pollen morphotype from gut compression of a Cretaceous insect, and its bearing on palynomorphological evolution and palaeoecology. Cret. Res. 24, 149–156 (2003).

Vilhelmsen, L. The preoral cavity of lower Hymenoptera (Insecta): comparative morphology and phylogenetic significance. Zool. Scr. 25, 143–170 (1996).

Krassilov, V. A. & Bugdaeva, E. V. An angiosperm cradle community and new proangiosperm taxa. Acta Palaeobot. Suppl. 2, 111–127 (1999).

Krassilov, V. A. Paleoecology of Terrestrial Plants. Basic Principles and Techniques pp. 283 (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1975).

Kvaček, J. & Pacltová, B. Bayeritheca hughesii gen. et sp. nov., a new Eucommiidites-bearing pollen organ from the Cenomanian of Bohemia. Cret. Res. 22, 695–704 (2001).

Abbink, O. A., Van Konijnenburg-Van Cittert, J. H. A. & Visscher, H. A sporomorph ecogroup model for the Northwest European Jurassic–Lower Cretaceous: concepts and framework. Geol. Mijnb. 83, 17–31 (2004).

Labandeira, C. C. in The evolutionary biology of flies (eds D. Yeates and B. M. Wiegmann) pp. 217–273 (Columbia Univ. Press, New York, 2005).

Peñalver, E. et al. Thrips pollination of Mesozoic gymnosperms. PNAS 109, 8623–8628 (2012).

Peris, D., Peñalver, E., Delclòs, X., Barrón, E., Pérez-de la Fuente, R., & Labandeira, C. C. False blister beetles and the expansion of gymnosperm–insect pollination modes before angiosperm dominance. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2017.02.009 (2017).

Cai, Ch., et al. Beetle pollination of cycads in the Mesozoic. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.036 (2018).

Mao, Y., et al. Various amberground marine animals in Burmese amber with discussions on its age. Palaeoentomol. https://doi.org/10.11646/palaeoentomology.1.1.11 (2018).

Caldas, M. B., Martins-Neto, R. G., and Lima-Filho, F. P. Afropollis sp. (polén) no trato intestinal de vespa (Hymenoptera: Apocrita: Xyelidae) no Cretáceo da Bacia do Araripe. Atas II Simpos. Nacion. Estud. Tectonico Soc. Brasil. Geologia 195–196 (1989).

Doyle, J. A., Jardiné, S. & Doerenkamp, A. Afropollis, a new genus of early angiosperm pollen, with notes on the Cretaceous palynostratigraphy and paleoenvironments of Northern Gondwana. Bull. Cent. Recher. Explor. Prod. Elf. Aquitaine 6, 39–117 (1982).

Doyle, J. A., Hotton, C. L. & Ward, J. V. Early Cretaceous tetrads, zonasulcate pollen, and Winteraceae II. Cladistic analysis and implications. Am. J. Bot. 77, 1558–1568 (1990).

Friis, E. M, Crane, P. R. & Pedersen, K. R. Early Flowers and Angiosperm Evolution. pp 585 (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2011).

Poinar, G. Jr Cascoplecia insolitis (Diptera: Cascopleciidae), a new family, genus, and species of flower-visiting, unicorn fly (Bibionomorpha) in Early Cretaceous Burmese amber. Cret. Res. 31, 71–76 (2010).

Grimaldi, D. A. & Ross, A. J. in Terrestrial Conservation Lagerstätten, Windows into the Evolution of Life on Land (eds N. C. Fraser & H.-D. Sues) pp. 287−342 (Dunedin, Edinburg, 2017).

Zhang, Q., Rasnitsyn, A. P., Wang, B. & Zhang, H. Hymenoptera (wasps, bees and ants) in mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber: a review of the fauna. Proc. Geol. Assoc. 129, 736–747 (2018).

Brothers, D. J. Phylogeny and evolution of wasps, ants and bees (Hymenoptera, Chrysidoidea, Vespoidea and Apoidea). Zool. Scr. 28, 233–250 (1999).

Brothers, D. J. & Carpenter, J. M. Phylogeny of Aculeata: Chrysidoidea and Vespoidea (Hymenoptera). J. Hym. Res. 2, 227–304 (1993).

Rasnitysn, A. P. Hymenoptera-Apocrita of the Mesozoic. Trudy Paleontolog. Instit. Akad. Nauk SSSR 147- 1-1321975) [In Russian].

Pacltová, B. Palynological study of Angiospermae from the Peruc Formation (?Albian–Lower Cenomanian) of Bohemia. Sborník Geol. vĕd, Paleontol. Přada 13, 105–139 (1971).

Ward, J. V. Early Cretaceous angiosperm pollen from the Cheyenne and Kiowa Formations (Albian) of Kansas. USA Palaeont. Abteil. B 202, 1–81 (1986).

Barrón, E. et al. Palynology of Aptian and upper Albian (Lower Cretaceous) amber-bearing outcrops of the southern margin of the Basque-Cantabrian basin (northern Spain). Cret. Res. 52, 292–312 (2015).

Peyrot, D., Barrón, E., Polette, F., Batten, D. J. & Néraudeau, D. Early Cenomanian palynofloras and inferred resiniferous forests and vegetation types in Charentes (southwestern France). Cret. Res. 94, 168–189 (2019).

Cruickshank, R. D. & Ko, K. Geology of an amber locality in the Hukawng Valley, Northern Myanmar. J. Asian Earth Sci. 21, 441–455 (2003).

Coiro, M., Doyle, J. A., & Hilton, J. How deep is the conflict between molecular and fossil evidence on the age of angiosperms? New Phytol. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.15708 (2019)

Crepet, W. L., Nixon, K. C., Grimaldi, D. & Riccio, M. A mosaic Lauralean flower from the Early Cretaceous of Myanmar. Am. J. Bot. 103, 290–297 (2016).

Liu, Z.-J., Huang, D., Cai, C., & Wang, X. The core eudicot boom registered in Myanmar amber. Sci. Rep. 8 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35100-4 (2018).

Poinar, G. O. & Chambers, K. L. Palaeoanthella huangii gen. and sp. nov., an early Cretaceous flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. Sida 21, 2087–2092 (2005).

Poinar, G. O. & Chambers, K. L. Endobeuthos paleosum gen. et sp. nov., fossil flowers of uncertain affinity from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber. J. Bot. Res. Instit. Tex. 12, 133–139 (2018).

Poinar, G. O. Programinis burmitis gen. et sp. nov., and P. laminatus sp. nov., Early Cretaceous grass-like monocot in Burmese amber. Austr. Syst. Bot. 17, 497–504 (2004).

Poinar, G. O., Chambers, K. L. & Buckley, R. Eoëpigynia burmensis gen. and sp. nov., an early Cretaceous eudicot flower (Angiospermae) in Burmese amber. J. Bot. Res. Instit. Tex. 1, 91–96 (2007).

Atkinson, B. A., Stockey, R. A. & Rothwell, G. A. Tracking the initial diversification of asterids: anatomicaly preserved Cornalean fruits from the Early Coniacian (Late Cretaceous) of western North America. Int. J. Plant Sci. 179, 21–35 (2018).

Kevan, P. G. & Baker, H. G. Insects as flower visitors and pollinators. Ann. Rev. Entom. 28, 407–453 (1983).

Jud, N. A. Fossil evidence for a herbaceous diversification of early eudicot angiosperms during the Early Cretaceous. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 282, 20151045 (2015).

Magallón, S., Gómez‐Acevedo, S., Sánchez‐Reyes, L. L. & Hernández‐Hernández, T. A metacalibrated time‐tree documents the early rise of flowering plant phylogenetic diversity. New Phytol. 207, 437–453 (2015).

Hughes, N. F. & McDougall, A. B. Barremian-Aptian angiospermid pollen records from southern England. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 65, 145–151 (1990).

Chambers, K. L., Poinar, G. O. & Buckley, R. Tropidogyne, a new genus of Early Cretaceous eudicots (Angiospermae) from Burmese amber. Novon 20, 23–29 (2010).

Crepet, W. L. The fossil record of angiosperms: requiem or renaissance? Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 95, 3–34 (2008).

Danforth, B. N. & Poinar, G. O. Morphology, classification, and antiquity of Melittosphex burmensis (Apoidea: Melittosphecidae) and implications for early bee evolution. J. Paleo. 85, 882–891 (2011).

Grimaldi, D. A. Basal Cyclorrhapha in amber from the Cretaceous and Tertiary (Insecta, Diptera), and their relationships. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 423, 1–97 (2018).

Menzel, R. & Müller, U. Learning and memory in honeybees: from behavior to neural substrates. Ann. Rev. Neurosci. 19, 379–404 (1996).

Zeil, J., Kelber, A. & Voss, R. Structure and function of learning flights in ground-nesting bees and wasps. J. Exp. Biol. 199, 245–252 (1966).

Jones, P. L. & Agrawal, A. A. Learning in insect pollinators and herbivores. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62, 53–71 (2017).

Farris, S. M. & Schulmeister, S. Parasitoidism, not sociality, is associated with the evolution of elaborate mushroom bodies in the brains of hymenopteran insects. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 278, 940–951 (2010).

Carpenter, J. M. & Rasnitsyn, A. P. Mesozoic Vespidae. Psyche 97, 1–20 (1990).

Perrard, A., Grimaldi, D. A. & Carpenter, J. M. Early lineages of Vespidae (Hymenoptera) in Cretaceous amber. Syst. Ent. 42, 379–386 (2017).

Grimaldi, D. A. Diverse orthorrhaphan flies (Diptera: Brachycera) in amber from the Cretaceous of Myanmar. Brachycera in Cretaceous amber, part VII. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 408, 131 (2016).

Feild, T. S., Arens, N. C., Doyle, J. A., Dawson, T. E. & Donoghue, M. J. Dark and disturbed: a new image of early angiosperm ecology. Paleobiol 30, 82–107 (2004).

Grimaldi, D. The co-radiations of pollinating insects and angiosperms in the Cretaceous. Ann. Miss. Bot. Gard. 86, 373–406 (1999).

Shi, G. et al. Age constraint on Burmese amber based on U-Pb dating of zircons. Cret. Res. 37, 155–163 (2012).

Punt, W., Hoen, P. P., Blackmore, S., Nilsson, S. & Le Thomas, A. Glossary of pollen and spore terminology. Rev. Palaeobot. Palynol. 143, 1–81 (2007).

Hesse, M. et al. Pollen Terminology. An Illustrated Handbook. pp. 266 (Springer, Vienna, 2009).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Schindelin, J., et al., The ImageJ ecosystem: an open platform for biomedical image analysis. Mol. Reprod. Develop. PMID 26153368 (2015).

Preibisch, S., Saalfeld, S. & Tomancak, P. Globally optimal stitching of tiled 3D microscopic image acquistions. Bioinformatics 25, 1463–1465 (2009).

Fedorov, A. et al. 3-D Slicer as an image computing platform for the quantitative imaging network. Magn. Reson. Imag. 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

APG-Angiosperm Phylogeny Group IV. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20 (2016).

Acknowledgements

AMNH CT instrumentation was made possible through U.S. NSF grant EAR 0959384. This study is a contribution to the project CRE, funded by the Spanish AEI/FEDER, UE Grant CGL2017-84419. We are grateful to Keith Luzzi, Steve Thurston, and Steve Davis (AMNH) for their contributions to this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.G. was involved in discovery, preparation, study of the specimen, and it’s description. E.P. and E.B. studied the wasp and pollen, respectively, and mapped pollen grains. H.H. worked on CT scanning of the specimen. M.S.E. examined morphology of the wasp. Interpretation of data were provided by all authors. The manuscript was compiled by D.G., E.P., and M.S.E.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grimaldi, D.A., Peñalver, E., Barrón, E. et al. Direct evidence for eudicot pollen-feeding in a Cretaceous stinging wasp (Angiospermae; Hymenoptera, Aculeata) preserved in Burmese amber. Commun Biol 2, 408 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0652-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-019-0652-7

This article is cited by

-

The angiosperm radiation played a dual role in the diversification of insects and insect pollinators

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Necrophagy by insects in Oculudentavis and other lizard body fossils preserved in Cretaceous amber

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Unparalleled details of soft tissues in a Cretaceous ant

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2022)

-

A new marsh beetle from mid-Cretaceous amber of northern Myanmar (Coleoptera: Scirtidae)

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

The earliest beetle with mouthparts specialized for feeding on nectar is a parasitoid of mid-Cretaceous Hymenoptera

BMC Ecology and Evolution (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.