Abstract

Sustainability in the Anthropocene requires social cooperation and learning against a backdrop of increasingly complex, polycentric governance. Here, we introduce an institutional navigation framework emphasizing how individuals pursue their policy goals within polycentric sustainability governance. We illustrate the utility of the framework by exploring how actors navigate institutional complexity to increase collective welfare and adaptive capacity in California’s San Francisco Bay, in contrast with protecting self-interest and constraining adaptive capacity on Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef. Our analysis provides: (1) a normative perspective on how institutional navigation may or may not support sustainability; (2) initial theoretical hypotheses about understudied strategies used by policy actors to advance or constrain sustainability; and (3) some practical ideas for policy actors seeking to strategically achieve complex sustainability goals in polycentric systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Global sustainability challenges such as climate change expose three defining characteristics of the Anthropocene. First, we live in an increasingly interconnected, global society challenged by cooperation problems across multiple scales. Second, global sustainability issues are governed by complex, polycentric institutional arrangements where multiple institutions and actors engage in different forms of self-organization to manage such cooperation problems1,2,3. Third, increasingly complex knowledge systems seriously challenge our ability to deliver salient, credible and legitimate scientific information to policymakers4. These challenges are not limited to climate change1; they also confound problems of global public health5,6, international trade7, national security8, common-pool resources9 and many other pressing sustainability issues.

We argue that a change in thinking is urgently needed from both the scientists studying these multi-level cooperation problems and policymakers striving to solve them. Rather than simply mapping or bemoaning their complexity, we must accept the reality of polycentric governance and learn the art of institutional navigation10,11. Polycentric systems are multiscale political systems with many centres of decision-making, which can be conceptualized as an ecology of games with multiple policy actors, policy venues and interdependent policy issues that require learning and cooperation12. Institutional navigation is the process of strategically selecting which of these venues to participate in, which actors to collaborate with, what issues to focus on and which decision-making strategies to employ across the complex system.

The concept of institutional navigation is important because it emphasizes individual agency: how actors make decisions and provide leadership in polycentric systems to achieve their individual and collective goals11. Individual agency rarely features in analyses of polycentric systems, which are still dominated by normative structural perspectives that describe and often prescribe the connective possibilities of polycentric governance. Indeed, in many analyses, polycentric governance is often promoted as the preferred alternative to centralized, top-down institutional arrangements13,14. However, in reality, most governance is now polycentric; therefore, the important question does not relate to which governance model is most appropriate, but rather how polycentric governance varies across social–ecological contexts to facilitate cooperation and learning15,16,17,18. Answering this question requires analysis of how individual agency interacts within complex institutional structures to produce sustainability governance outputs and outcomes.

In jointly considering individual decision-making and the structure of polycentric governance, we build here on previous actor-centric ideas from across the policy sciences, such as venue shopping19, policy entrepreneurship20 and actor-centred institutionalism21. These previous ideas have not yet explicitly incorporated polycentric governance as a fundamental component of the analysis of individual decision-making. However, policy scientists are increasingly recognizing the importance of polycentric governance for global challenges such as climate change22, and of how individual decision-makers are exerting agency in such systems to pursue sustainability transformations23. The concept of institutional navigation thus links an explicit focus on individual agency with the normative structural approach that dominates the existing literature on polycentric governance.

In this Perspective, we develop a framework for institutional navigation that includes four critical elements (Fig. 1):

-

Knowledge: how do actors cultivate awareness of the science, venues, players, politics and indeed self?

-

Relationships: what does it mean to develop trust, avoid overcommitment, select partners and leverage different types of social capital?

-

Strategies: how do actors choose or shift venues and how do they approach externalities, goal setting, cooperation and leadership allocation?

-

Decisions and implementation: can actors explicitly identify and sequence their sustainability goals and, more broadly, is uncertainty a fact of complex institutional life or a quality to be minimized?

Because polycentric systems involve many centres of decision-making operating at different time scales, feedbacks often occur between these different elements of institutional navigation. Institutional navigation thus does not follow a strictly ordered pathway; rather, strategies and decisions can emerge at any point in time, from a basis of knowledge and relationships that have accumulated over time. The elements offer us a set of working hypotheses to guide analysis of the critically under-researched issue of individual decision-making in polycentric systems.

Our purpose in developing the institutional navigation framework is also not just analytical; it serves two additional purposes: practical and normative. Practically, institutional navigation offers strategic guidance to real-world stakeholders who are seeking to achieve their sustainability goals in the complex, polycentric systems they face every day. Normatively, we argue that while institutional navigation can be used to achieve self-interested goals that decrease sustainability, we recommend that it be used towards the pursuit of collective goals that increase sustainability.

The concept of institutional navigation thus has the potential to connect theories that focus on structure (including polycentric governance12, institutional analysis24,25 and social–ecological systems26,27) with theories of the policy process that emphasize how individual actors strategically participate in different types of policy venue and employ different strategies in each venue21,28,29,30. It enables us to ask what kinds of actors use different strategies of institutional navigation, how often, and what are the consequences for the capacity of polycentric systems to achieve sustainability?

To illustrate the concept’s potential, we explore institutional navigation in two longstanding and intensively studied cases: San Francisco Bay, California (SFB)31,32 and the Great Barrier Reef, Queensland (GBR)33,34, drawing on our own research experience and policy engagement in these cases. In SFB, institutional navigation strategies are being used to enhance coordination for adaptive capacity and sustainability. In contrast, institutional navigation strategies are constraining adaptive capacity and sustainability in the GBR through protecting existing economic activity. These cases are used here as a soft test of the hypotheses or assumptions of institutional navigation. While more fully fledged and comparative analyses across a bigger and more diverse set of social–ecological systems are needed, this is a starting point to illustrate the usefulness of the framework for exploring the full range of opportunities and pitfalls of navigation within polycentric governance systems.

Institutional navigation in polycentric governance

Here, we explore the key elements of institutional navigation depicted in Fig. 1. For each element, we summarize the key idea with reference to existing research. We then explore the practical possibilities through examples in SFB and the GBR.

Knowledge

Navigating a system requires developing knowledge about the biophysical and social aspects of coupled human–natural systems. Deep expertise in one aspect must be complemented with broader knowledge of the overall system to appreciate the interdependencies involved. The most effective leaders within the system—and often the most experienced—may have more complete mental models of the whole system35. Often, when policy scientists present policymakers with a picture of a polycentric system (for example, a visualization of a policy network), the immediate benefit they mention is being able to fully grasp the complexity they face every day (while also appreciating a researcher with a sympathetic ear).

Knowing the science

Incorporating the best available science for evidence-based decisions is a normative goal for governance, and often a legal requirement36. Usually this means understanding the biophysical and social processes in a system that affect the sustainability outcomes that people care about. In polycentric systems, the science enterprise or knowledge system4 is spread across multiple venues and organizations, including researchers in universities, non-governmental agencies and governmental agencies. Data collection and research projects, which are often driven by legal and regulatory mandates, combine to define the overall system. Hence, decision-makers need to understand the drivers of outcomes, as well as the structure of the overall science enterprise, so that they can access the correct knowledge, data and expertise.

Knowing the venues

Polycentric governance systems are composed of multiple policy venues, where groups of policymakers collectively deliberate and make decisions29. As a first step, individual decision-makers need to know which venues exist and how to access them. Effective policy actors seek to understand how the venue was established, as well as the authority and resources that are being considered within the venue. This includes knowing which other organizations are participating in the venue and how decisions made in the venue may affect decisions in other venues and on-the-ground implications for specific environmental issues. It is also important to understand the formal and informal rules governing collective decision-making within the venue, as well as the history of interaction among participating actors, to effectively influence the decision-making process.

Knowing the players

Polycentric systems may involve hundreds of different organizations, some of which can be identified as members of advocacy coalitions30 or issue networks37 pursuing common policy goals. It is important to understand who is currently participating in the system, their policy goals, their reputations based on past interactions, and their levels of political influence. It is also important to know who is currently excluded from the system, either because they should be included for reasons of equity, legitimacy and effectiveness or because they could pursue external political strategies such as litigation or legislation that may threaten cooperation within the system. To effectively bargain over potential policy agreements, it is also important to understand the range of interests and policy preferences held by different decision-makers.

Knowing the politics

Skilful navigation of politics is critical to effective governance38. Broader political context is an important shaper of the relative priorities and influence of key institutions and actors in polycentric systems. By broader political context, we mean, for example: broader ideological, demographic, economic and employment shifts in the community; political changes at higher levels of government; and external and seemingly unrelated political problems such as budget deficits. Changes in the political context often open windows of opportunity for institutional change that might not otherwise be possible. Understanding how decision-makers are affected by this broader political context assists with working out which strategies are politically feasible within a polycentric system, as well as how to navigate around political constraints (such as a budget deficit) and political opportunities (such as an upcoming election).

Knowing the self

Every individual or organization, whether they are a policy practitioner or a policy scientist, has an established set of values, attitudes, beliefs and behavioural routines39. Yet, this established psychological repertoire is rarely examined in a systematic manner, despite influencing decisions every day. Effective policy actors routinely clarify their own values and goals with respect to navigating the system. They also assess their understanding of the system itself: what venues exist, what issues do they address, who are the actors and where can participation make the biggest difference? Policy actors who do not have clear enough answers to these questions can improve their awareness by researching the system and reflecting on the pragmatic power they possess to pursue particular goals and strategies.

Relationships

Effective polycentric governance relies on building relationships with other actors to increase cooperation, facilitate social learning and make policy agreements. Such relationships constitute policy networks that are the basis for policy communities both within and across policy venues40.

Choosing partners

From the perspective of an individual, the best partners are trustworthy, share one’s policy goals and have access to political influence and other resources41. Trustworthy partners are competent and have a reputation for living up to their commitments. Actors who share policy goals can form advocacy coalitions that pool resources to pursue a common agenda across the system. Actors who have political influence or access to expertise or financial resources can usually have a larger effect on decisions and the behaviour of other actors, as well as a higher likelihood of changing the structure of the system42.

It is also important to think about actors who would not be good partners. All policy systems contain individuals or organizations who seek to upset cooperation or political agreements. Sometimes this is just a personality trait (for example, in people who lack empathy or always pursue their individual self-interest over collective benefits). Overall, these personalities are toxic to cooperation and should be avoided when seeking participants in collective decisions. At other times, actors may be seeking to disrupt a system that they view as unfair or believe is not delivering the policies they want. These actors deserve a voice and can also be directed to venues that are more designed for adversarial interaction, such as the courts or legislature. This is not to say that diversity in values, background or policy preferences should be minimized, but rather that cooperation is more likely to evolve when people share the basic values of collaboration.

Developing trust

Cooperation is built on trust and trust emerges from a social process of repeated interaction and norms of reciprocity43,44. Policy actors are more likely to be trusted when they are perceived to keep their promises, be competent and share the same values and goals45,46. Trustworthy actors are more likely to be selected as partners, invited to participate in decisions, survive longer in the system and gain political influence over time. Trust takes time to develop but can be lost quickly.

Mixing bridging and bonding social capital

Social capital is based on networks of relationships that provide some type of value to the individual or group. The most discussed type of social capital is bonding social capital, which entails overlapping and repeated relationships among an enduring community of cooperators47. Bonding social capital is a foundation for cooperation and requires repeated interactions with the same people, usually in the same venues. In contrast, bridging social capital means connecting across social or physical boundaries and developing relationships with new people in new venues. Bridging social capital provides access to new information and resources, as well as opportunities for brokerage and leadership. Effective networking requires developing a portfolio of bonding and bridging social capital, then carefully choosing which actors with whom to form repeated relationships and which new communities to branch out to.

Strategic commitment

It is easy to become overcommitted in polycentric systems because there are so many venues and issues that could be addressed. Practitioners often complain about participation fatigue48. Overcommitted actors often fail to deliver their promises, which reduces trust. A more effective strategy is to strategically choose partners, venues, issues and projects that are important for the overall function of the system. While such strategies typically lead to incremental change, they can accumulate over time to make meaningful changes in the system and sometimes push a system across the threshold for more transformative change19,28.

Strategies

Once sufficient levels of knowledge and relationships are developed, decision-makers can think about what strategies they can adopt to pursue their individual or collective goals. By strategies, we mean actively participating in polycentric systems, and the sequence and nature of decision-making.

Choosing venues

Not all policy venues are created equal; some entail more important decisions than others, depending on the amount of resources allocated, the level of authority to affect different parts of the system, and the political influence of involved players19. Effective policy actors typically seek to participate in the big venues that will make a difference. A good cue for beneficial venues is attention and participation from leaders and big players from other important organizations. Resources expended in less important venues often have low payoffs. There are exceptions to this rule—smaller venues can be useful for creating bridging social capital, for lower-risk innovation or for developing small wins and trust49. Hence, effective decision-makers usually participate in a portfolio of venues.

Thinking about externalities

Decisions made in one venue often have negative or positive spillover effects, or externalities, that affect other venues49. Effective decision-makers always think about how their decisions may shape other parts of the system and how decisions made in other venues may constrain or enable the decisions made in the venue they are currently participating in. For example, decisions about water supply and flooding have direct implications for water quality and biodiversity, and decisions about land use may affect coastal ecosystems. Polycentric systems also generate strategy externalities, where decision-makers export a strategy that was successful in one venue into another venue where the strategy is inappropriate50. Hence, effective decision-makers actively think about which strategies to adopt in different venues, rather than assuming one strategy will work in all situations.

Building on small wins

Success is built iteratively: the reputation of an individual, and overall policy change in a system, does not happen instantaneously. Rather, individual reputation and policy change emerge from a policy process that involves repeated interaction across multiple venues. Pursuing small wins in less important venues is a mechanism for building a trustworthy reputation, as well as establishing the resources and institutional infrastructure for pursuing big wins in more important venues49,51. Small wins may also create knowledge and examples that can be scaled up to larger goals.

Relying on cooperation

Policy actors often express the instinct to rely on sticks or enforcement to compel actors to engage in specific behaviours and sanction undesirable decisions. Existing research clearly supports the importance of graduated sanctions against non-cooperators52. However, sanctions are far more costly than relying on the carrot of cooperation. Other research has shown that without a high level of cooperation, social systems will fall apart—cooperation is the fundamental glue of complex social organization. Hence, cooperation and agreement are typically the first approach, and sanctions and conflict are used only as necessary and in a graduated manner. That said, there are certainly times when enforcement and sanctions are needed to change behaviour or redistribute political power in order to upset political institutions that are undesirable from an individual or collective perspective.

Allocating leadership

Leadership is a crucial resource for the evolution of cooperation in polycentric systems, which involve organizations that are usually complex enough to have specialized divisions, including leadership and staff53. Organizational leaders usually have more political influence than staff, and can speak for and direct the resources of the organization. However, organizational leaders cannot attend every venue all the time—they must strategically choose to attend the highest-priority venues where their influence is most important. Decisions made in these high-priority venues then percolate throughout the system. Lower-level staff can effectively manage other venues, when they involve less important decisions that need to be monitored or require some type of specialized technical expertise that the leaders cannot provide. Staff may also have greater longevity in an organization, which makes them an important source of institutional knowledge and a mechanism for maintaining interorganizational networks of cooperation. Successful organizations need to strategize about the effective allocation of leadership and staff across different types of venue.

Adjusting decision rules

At any given time, a polycentric system features a set of existing policy venues, with rules governing decision-making within each venue, and the potential that decision-making in one venue may purposely or accidentally affect decisions in other venues54,55. These institutional parameters are potentially subject to change in the pursuit of new goals. New venues can be created to address emerging problems or to better integrate across fragmented decision-making. The rules governing existing venues (for example, in relation to the process of making decisions, who is invited to participate, the scope of issues considered or how the venue considers decisions in other venues) could be changed. Existing institutions can sometimes be barriers to achieving goals and should be removed or circumnavigated. However, changing institutions is one of the costliest strategies and may involve extensive political negotiation or movement to higher-level venues such as the legislature or administrative leadership. Hence, in many cases, it may be easier to adjust strategies within the existing institutional structures.

Decisions and implementation

The collective result of individual navigation strategies is a set of decisions and associated policy implementation targeting system-level outcomes. Policy scientists distinguish between outputs such as plans and policy decisions and outcomes for the environmental, economic or social issues targeted by the policies. When policymakers articulate their goals, they are usually referring to producing some type of output or changing some outcome. The outputs are usually necessary but not sufficient initial steps to produce outcomes; there is always a risk of paper plans or symbolic/placebo policy56,57,58.

Explicitly sequencing goals

There are many reasons for explicitly identifying and sequencing desired goals. For example, it makes sense to eliminate or at least neutralize existing perverse incentives that are creating a problem before introducing new constructive instruments addressing that problem. For example, where a tax concession encourages coal mining and induces unacceptable carbon emissions, it is more efficient to remove the tax concession than to prohibit coal mining altogether. Likewise, social and institutional capacity might need to be built into a system before rolling out changes on the ground, such as large-scale ecosystem restoration59. Less intrusive and interventionist outcomes should be ordered before more intrusive ones; this nurtures virtue in the system and means that escalating to more interventionist responses is only necessary when less intrusive outcomes are not enough.

Accepting uncertainty

Uncertainty is an inherent feature of environmental governance. Environmental outcomes are a product of multiple causal processes that operate at different time scales and feature nonlinear dynamics. It is usually very difficult to attribute a policy outcome to one particular venue or decision in a polycentric system and surprise is inevitable. While it is important to utilize the best available science and knowledge at a certain time point, uncertainty should not become an impassable barrier to decision-making. Instead, polycentric systems require adaptive management and monitoring of outcomes over time to make it as easy as possible to adjust institutions considering surprises and new information. Policymakers can achieve this by incorporating scientific uncertainty into decision-making as knowledge, not ignorance60.

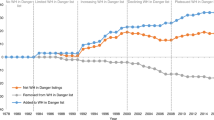

Climate change adaptation in SFB and the GBR

We illustrate the applicability and usefulness of the framework with two cases of polycentric governance of climate adaptation in SFB and the GBR. These cases demonstrate the importance of institutional navigation, and the contrasting adaptation pathways in each of them highlight how institutional navigation can be used to pursue collective goals that may increase sustainability but also self-interested goals that constrain it. While the two cases are not fully representative of the wide range of social–ecological systems to which the framework could be applied, they provide the opportunity to explore institutional navigation in action and how it helps researchers compare adaptation pathways. We selected them because of the authors’ deep research and policy engagement in both cases, and because they are both coastal systems facing a central climate impact: sea level rise and flooding in SFB (Fig. 2); and coral bleaching due to warming waters in the GBR (Fig. 3). Importantly, addressing these impacts requires overcoming the same central governance challenge in both regions: developing new institutional arrangements to coordinate adaptation activities at the regional level. However, the institutional navigation strategies used by the actors in each system have put them on potentially contrasting pathways with respect to adaptive capacity and sustainability. SFB has witnessed a major investment in the development of new governance institutions to address sea level rise, while the impact of warming waters on the GBR has become a political hot potato characterized by placebo policies and governance traps.

The SFB ferry is an iconic component of San Francisco’s coastal infrastructure and is an international tourism hotspot. Sea level rise is an important climate change vulnerability in the SFB area of California, which features high levels of coastal development and critical infrastructure. Credit: California King Tides Project.

The 2019 Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report assessed the overall outlook for the reef as very poor, and in 2020, global heating caused the corals on the GBR to bleach again for the third time in 5 years, generating grave concerns about the ecosystem’s future ability to recover before yet another bleaching event. Credit: Greg Torda, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

The comparison of the two cases using this framework is summarized in Table 1. The main difference is that SFB has experienced a major growth in sea level rise adaptation institutions, which is a signal of a high-capacity system with widespread agreement about the importance of the problem. However, this institutional growth has also exacerbated the coordination and fragmentation problems characteristic of polycentric systems. To address these issues, in 2019, the San Francisco Bay Conservation and Development Commission convened the forum Bay Adapt: Regional Strategy for a Rising Bay with the main goal of identifying a collective vision for sea level rise adaptation, creating the basis for a regional plan and deliberating on potential new institutional arrangements. Bay Adapt highlights several key navigation strategies that help to increase adaptive capacity. Bay Adapt requires knowledge of the existing venues and actors already engaged in some type of climate adaptation, as well as deliberation over how to integrate and coordinate activities towards a common goal. Bay Adapt is designed to develop trust and includes actors from different communities within the governance network known to be influential and with a reputation for being able to collaborate with others. Equity and climate justice are central themes for Bay Adapt, so they have invited participation from established environmental justice leaders and organizations in SFB. Bay Adapt is also seeking to first make a small win by establishing a collective vision and joint platform, which may then pave the way for more permanent institutional change. In other words, the leadership group is sequencing goals rather than attempting to immediately achieve the final goal of identifying and establishing the appropriate institutional arrangements for coordinated adaptation.

In contrast, concerned actors in the GBR must navigate a variety of influential players jostling for power and the increasingly polarized politics of climate change in Australia. To resolve this political problem, the Australian environmental department has recently sought to bypass the traditional lead actors in the system in favour of working directly with a newer and smaller private organization, the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, with the main goal of neutralizing the politics of climate change and creating a basis for industry- and technology-led solutions to adaptation (not mitigation). The alliance with the Great Barrier Reef Foundation illustrates several key navigation strategies that may constrain adaptive capacity. For knowledge, the new leadership group is reshaping the politics of climate change by promoting technology-led adaptation over community-based adaptation and mitigation strategies. For relationships, the new leadership group is using their substantial funding to incentivize weaker actors in the system to support technology-led adaptation solutions33,57. In terms of strategies, the new leadership group is focusing its approach on technology-led solutions in the water (for example, coral shading, cryopreservation and coral-seeding robots), rather than more meaningful changes in the fisheries, tourism, mining and agricultural communities, which are dependent on or immediately adjacent to the reef. In other words, the new leadership group is deliberately circumnavigating existing venues and sequencing goals to reduce the influence of some actors, closing off some potential adaptation pathways altogether.

By recognizing the roles of different actors in polycentric systems, it becomes clear that there are analytical and practical possibilities as a result of institutional navigation, as well as pitfalls. The case studies demonstrate how institutional navigation strategies are present in governance processes that both increase and constrain adaptive capacity to climate change impacts. The contrast in adaptation pathways between the GBR and SFB suggests that further research applying institutional navigation can support practical, normative and analytical goals. Analysing the types of institutional navigation strategies that are most effective for pursuing the normative goals of sustainability can provide the basis for practical recommendations and training of decision-makers.

Pursuing sustainability with institutional navigation

Revitalizing and extending our understanding of institutional navigation provides an important new perspective for polycentric sustainability governance. The framework directs attention to how individual actors strategically participate in polycentric processes to achieve their policy goals. Advancing the approach—as a theory and a practical endeavour—may help to resolve the sustainability problems of the Anthropocene, ranging from short-term, fast-moving crises (such as pandemics and wildfires) to long-term, slow-moving problems (such as sea level rise and recurrent heatwaves). In doing so, institutional navigation builds on other frameworks that emphasize individual agency, and complements recent inroads based on structural analysis of institutional rules and network patterns of participation and collaboration. However, several research and practical challenges remain.

First, a better understanding of the role of professional norms in public and scientific leadership needs to be developed to minimize the risk of institutional navigation being used to achieve self-interested goals that decrease sustainability, rather than collective goals that increase it. The case studies reveal the potential for conflict between the system-level goals of increasing cooperation, resilience and adaptive capacity and the individual goals of specific actors seeking to protect the status quo of existing activities and political power. Policy practitioners and sustainability scientists need advice about how to reconcile their individual policy goals with the collective goals of enhancing the resilience and equity of social–ecological systems. Instilling norms of public service motivation into organizational culture, leadership and individual professional development can help to align navigation strategies with the broader collective goals of sustainability. The aftermath of the 2020 US presidential election and the ongoing fallout from COVID-19 clearly demonstrate the importance of individual actors either undermining or reinforcing collective goals.

Second, the framework inspires important questions for future research on individual decision-making in polycentric systems. For example, which elements of institutional navigation are most important for decision-makers, how do they learn to navigate and how are they effective at achieving policy goals? Also, how does institutional navigation co-evolve and interact with institutional and network structure to affect system performance? This includes recognizing that deploying all elements of institutional navigation may only be possible for high-capacity actors with sufficient resources. There may be trade-offs among different approaches to institutional navigation, and the resource demands of institutional navigation in increasingly complex governance systems have the potential to magnify existing inequities in procedural justice and sustainability outcomes. Research should identify efficiencies and shortcuts in institutional navigation, as well as how to build the capacities of stakeholder groups traditionally marginalized in sustainability governance.

Finally, this Perspective was informed by existing and emerging research on two cases: one in Australia and one in the United States. A more comprehensive set of case studies is needed to directly test the assumptions and working hypotheses of the institutional navigation framework and to understand how it might affect the dynamics and performance of polycentric governance more generally. The framework presented here is a starting point and needs to be tested and revised through additional empirical research well beyond the case studies presented to illustrate the feasibility of the idea. Linking case study analyses through a global network of social–ecological observatories would help answer some of the most important questions about the co-evolutionary dynamics of institutional navigation, actor networks and institutional structure. Such a shared research agenda going forward must include individual decision-making in polycentric governance as a central pillar. It must also draw on early and sustained engagement with the many scientists and policy practitioners resolutely navigating their science policy ships through the Anthropocene’s complex institutional storm.

References

Jordan, A. J. et al. Emergence of polycentric climate governance and its future prospects. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 977–982 (2015).

Galaz, V., Crona, B., Österblom, H., Olsson, P. & Folke, C. Polycentric systems and interacting planetary boundaries—emerging governance of climate change–ocean acidification–marine biodiversity. Ecol. Econ. 81, 21–32 (2012).

Ostrom, E. Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Glob. Environ. Change 20, 550–557 (2010).

Cash, D. W. et al. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 8086–8091 (2003).

DeWitte, S. N., Kurth, M. H., Allen, C. R. & Linkov, I. Disease epidemics: lessons for resilience in an increasingly connected world. J. Public Health 39, 254–257 (2016).

Lieberman, E. S. The perils of polycentric governance of infectious disease in South Africa. Soc. Sci. Med. 73, 676–684 (2011).

Morin, J.-F., Dür, A. & Lechner, L. Mapping the trade and environment nexus: insights from a new data set. Glob. Environ. Politics 18, 122–139 (2018).

Frank, A. B. et al. Dealing with femtorisks in international relations. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 17356–17362 (2014).

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. & Stern, P. C. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302, 1907–1912 (2003).

Berkes, F., Colding, J. & Folke, C. Navigating Social–Ecological Systems: Building Resilience for Complexity and Change (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Olsson, P., Folke, C. & Hughes, T. P. Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 9489–9494 (2008).

Lubell, M. Governing institutional complexity: the ecology of games framework. Policy Stud. J. 41, 537–559 (2013).

Biggs, R., Schlüter, M. & Schoon, M. L. Principles for Building Resilience: Sustaining Ecosystem Services in Social–Ecological Systems (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2015).

Steffen, W. et al. Trajectories of the Earth System in the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 8252–8259 (2018).

Berardo, R. & Lubell, M.Understanding what shapes a polycentric governance system. Public Adm. Rev. 76, 738–751 (2016).

Cole, D. H. Advantages of a polycentric approach to climate change policy. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 114–118 (2015).

Morrison, T. H. et al. The black box of power in polycentric environmental governance. Glob. Environ. Change 57, 101934 (2019).

Aligica, P. D. & Tarko, V. Polycentricity: from Polanyi to Ostrom, and beyond. Governance 25, 237–262 (2012).

Pralle, S. B. Venue shopping, political strategy, and policy change: the internationalization of Canadian forest advocacy. J. Public Policy 23, 233–260 (2003).

Mintrom, M.Policy entrepreneurs and the diffusion of innovation. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 41, 738–770 (1997).

Scharpf, F. W. Games Real Actors Play: Actor-Centered Institutionalism in Policy Research (Westview Press, 1997).

Jordan, A., Huitema, D., Van Asselt, H. & Forster, J. Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Herrfahrdt-Pähle, E. et al. Sustainability transformations: socio-political shocks as opportunities for governance transitions. Glob. Environ. Change 63, 102097 (2020).

North, D. C. Institutions, Institutional Change, and Economic Performance (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990).

Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1990).

Anderies, J. M., Janssen, M. A. & Ostrom, E. A framework to analyze the robustness of social–ecological systems from an institutional perspective. Ecol. Soc. 9, 18 (2004).

Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social–ecological systems. Science 325, 419–422 (2009).

Baumgartner, Frank. R. & Jones, B. D. Agendas and Instability in American Politics (Univ. Chicago Press, 2009).

Fischer, M. & Leifeld, P. Policy forums: why do they exist and what are they used for? Policy Sci. 48, 363–382 (2015).

Sabatier, P. A. & Jenkins-Smith, H. Policy Change and Learning: An Advocacy Coalition Approach (Westview, 1993).

Lubell, M. The Governance Gap: Climate Adaptation and Sea-Level Rise in the San Francisco Bay Area (Univ. California, Davis, 2017).

Lubell, M., Robins, G. & Wang, P. Network structure and institutional complexity in an ecology of water management games. Ecol. Soc. 19, 23 (2014).

Morrison, T. H. et al. Political dynamics and governance of World Heritage ecosystems. Nat. Sustain. 3, 947–955 (2020).

Morrison, T. H. Evolving polycentric governance of the Great Barrier Reef. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E3013–E3021 (2017).

Gray, S. et al. Purpose, processes, partnerships, and products: four Ps to advance participatory socio-environmental modeling. Ecol. Appl. 28, 46–61 (2018).

Cairney, P. The Politics of Evidence-Based Policy Making (Springer, 2016).

Gormley, W. T. Regulatory issue networks in a federal system. Polity 18, 595–620 (1986).

Young, O. R. Political leadership and regime formation: on the development of institutions in international society. Int. Organ. 45, 281–308 (1991).

Henry, A. D., Lubell, M. & McCoy, M. Belief systems and social capital as drivers of policy network structure: the case of California regional planning. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 21, 419–444 (2011).

Robins, G., Bates, L. & Pattison, P. Network governance and environmental management: conflict and cooperation. Public Adm. 89, 1293–1313 (2011).

Berardo, R. & Scholz, J. T. Self-organizing policy networks: risk, partner selection, and cooperation in estuaries. Am. J. Polit. Sci. 54, 632–649 (2010).

Silvia, C. Picking the team: a preliminary experimental study of the activation of collaborative network members. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 28, 120–137 (2018).

Axelrod, R. The Evolution of Cooperation (Basic Books, 1984).

Lyon, F. Trust, networks and norms: the creation of social capital in agricultural economies in Ghana. World Dev. 28, 663–681 (2000).

Hardin, R. The street-level epistemology of trust. Polit. Soc. 21, 505–529 (1993).

Levi, M. & Stoker, L. Political trust and trustworthiness. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 3, 475–507 (2000).

Berardo, R. Bridging and bonding capital in two‐mode collaboration networks. Policy Stud. J. 42, 197–225 (2014).

Wesselink, A., Paavola, J., Fritsch, O. & Renn, O. Rationales for public participation in environmental policy and governance: practitioners’ perspectives. Environ. Plan. A 43, 2688–2704 (2011).

Mewhirter, J., Lubell, M. & Berardo, R. Institutional externalities and actor performance in polycentric governance systems. Environ. Policy Gov. 28, 295–307 (2018).

Bednar, J. & Page, S. Can game(s) theory explain culture? The emergence of cultural behavior within multiple games. Ration. Soc. 19, 65–97 (2007).

Termeer, C. J. & Dewulf, A. A small wins framework to overcome the evaluation paradox of governing wicked problems. Policy Soc. 38, 298–314 (2019).

Gurerk, O., Irlenbusch, B. & Rockenbach, B. The competitive advantage of sanctioning institutions. Science 312, 108–111 (2006).

Wurzel, R. K., Liefferink, D. & Torney, D. Pioneers, Leaders and Followers in Multilevel and Polycentric Climate Governance (Routledge, 2019).

Lubell, M., Mewhirter, J. M., Berardo, R. & Scholz, J. T. Transaction costs and the perceived effectiveness of complex institutional systems. Public Adm. Rev. 77, 668–680 (2017).

Institutional Rational Choice: An Assessment of the Institutional Analysis and Development Framework (Westview Press, 2007).

Lubell, M. Collaborative environmental institutions: all talk and no action? J. Policy Anal. Manag. 23, 549–573 (2004).

Morrison, T. H. et al. Advancing coral reef governance into the Anthropocene. One Earth 2, 64–74 (2020).

Newig, J. Symbolic environmental legislation and societal self-deception. Environ. Polit. 16, 276–296 (2007).

Morrison, T. H. in Contested Country—Local and Regional Natural Resources Management in Australia 227–240 (CSIRO Publishing, 2009).

Bell, J. et al. Maps, laws and planning policy: working with biophysical and spatial uncertainty in the case of sea level rise. Environ. Sci. Policy 44, 247–257 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the US National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) under funding received from the US National Science Foundation DBI-1639145, ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (ARC CoE CRS) under funding received from the Australian Research Council CE-140100020 and National Science Foundation Critical Resilient Interdependent Infrastructure Systems and Processes grant number 1541056.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.L. co-wrote the article and conducted the case study research in SFB. T.H.M. co-wrote the article and conducted the case study research in the GBR. Both authors contributed equally to writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Sustainability thanks Paul Cairney and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lubell, M., Morrison, T.H. Institutional navigation for polycentric sustainability governance. Nat Sustain 4, 664–671 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00707-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-021-00707-5

This article is cited by

-

Moving from measurement to governance of shared groundwater resources

Nature Water (2023)

-

The emerging role of mega-urban regions in the sustainability of global production-consumption systems

npj Urban Sustainability (2023)

-

The governance of forest carbon in a subnational climate mitigation system: insights from a network of action situations approach

Sustainability Science (2023)

-

Incorporating human behaviour into Earth system modelling

Nature Human Behaviour (2022)

-

Urban planning in Swiss cities has been slow to think about climate change: why and what to do?

Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences (2022)