Abstract

Sustainable development of the ocean economy requires a system for measuring progress. The standard system of national accounting provides a solid foundation for doing so, though the scope requires expansion to adequately cover household-produced services; for example, ocean-based leisure, and the role of natural capital in the ocean economy. The accounts summary needs indicators beyond gross domestic product that enable users to choose what is included. New technologies make digital dashboards of indicators easy to produce. Such dashboards facilitate rapid comparison of indicators that cannot be aggregated into a single metric, which enables national ocean accounts to coherently present physical and monetary data.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

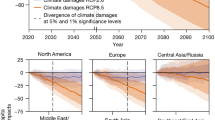

Countries and international organizations are setting ambitious ‘blue economy’ strategies for achieving a sustainable ocean economy1,2,3,4,5. Blue economies are devised to (1) increase production of current consumable output, business transactions and employment related to marine systems (including large lakes), (2) share the proceeds of production in an equitable way as means produced are converted into outcomes and improvements in well-being for people, and (3) conserve marine ecosystems and processes (Fig. 1). The blue economy concept for sustainable ocean development attempts to reconcile trends in the biophysical state of the ocean, such as deep-sea mining or offshore wind energy development, in order to maintain opportunities for future well-being, and enable emerging opportunities for ocean production to enhance current well-being6,7. Balancing new opportunities to produce the means for consuming more today while conserving future market and non-market opportunities requires measurement—to paraphrase Peter Drucker, you “can’t balance (improve) what you can’t measure”. A discussion of the measurement of the ocean economy or a strategy for meeting Sustainable Development Goals 14, 15.9 and 17.19 should start from the existing tools for measuring production, sustainability and social progress. The place to begin is the standardized system of national accounting, known as the System of National Accounts or SNA8. The SNA is the international standardized structure (sequence) of national accounts for measuring a country’s economy8. The SNA is extended for the environment and natural resources by the System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA), which also provides for integrated physical and monetary accounts9. Countries are increasingly implementing SEEA along with the SNA10, and we treat these for present purposes as one system.

Sustainable development at a minimum requires balance of three spheres of interest; production of opportunities today, distribution of those opportunities today, and allocating opportunities between today and tomorrow. Sustainable development is the intersection and balancing of these three areas of concern.

Measuring the blue economy requires more than a single indicator. The current national accounting headline indicator, gross domestic product (GDP), focuses on short-term production or mobilization of resources for current consumption. GDP is not especially useful for measuring blue development. This is because GDP does not reflect the long-term potential, distribution or outcomes of economic activity, among other reasons. GDP is an especially poor measure of development in frontier economies, like the ocean, where a substantial amount of resource mobilization is based on extraction of natural resources11. For the ocean economy, there is a need to fully develop national accounting indicators that capture changes in long-term economic possibilities (wealth) and measure the distribution of well-being (or welfare) and which can be disaggregated. These indicators include changes in the asset balance sheet, which tracks the stocks of assets and the value of assets included in the national accounts, and measures of real income and its distribution, where assets and real income are defined broadly.

Here, we adapt research commissioned by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy12 to examine the extent that the SNA, with its associated SEEA9,13, captures the necessary physical and monetary information for measuring progress towards sustainable (blue) economic development of the ocean. The standards and implementation conventions of the SNA and SEEA provide a solid foundation on which to build. We recommend some renovations to advance the holistic evaluation of ocean sustainability policy goals. These modifications involve reconsidering the scope or ‘boundaries’ of the national accounts and revisiting how the rich information in the accounts is summarized and presented. Rapid changes in technology and data availability and visualization make it feasible to show how multiple indicators change alongside monitoring dimensions.

Current national accounts and sustainable ocean development

An ocean account could be crafted with a subset and re-tabulation of national, regional or sectoral data that are ocean-specific. This would enable computation of ‘ocean GDP’. However, GDP and many other common macroeconomic statistics (for example, interest and unemployment rates) are inappropriate headline indicators to measure whether the ocean economy is developing sustainably. GDP is a macroeconomic aggregate that provides information about short-term production or mobilization of tradeable means. GDP is important for understanding the business cycle and for monetary and fiscal policy14. When production is not overly concentrated, rising GDP generally correlates with increasing well-being, especially in the poorest countries15 and in the post-World War II recovery period16. However, GDP hardly says anything about the second and third objectives of the blue economic development agenda that capture distributional effects and conservation priorities (Fig. 1).

While national accounts provide opportunities for measuring ocean sustainability, the current implementation of the SNA has important shortcomings. Most notably, it skews toward measuring production and promotes GDP as the headline measure. This is a narrower focus than that intended by the theory of national accounts. Besides missing opportunities, this implementation distorts discussions about social progress17,18,19. The SNA (sections 1.40–1.42) prioritizes information to manage fiscal and monetary policy, which leads to apparent inconsistencies; for example, allowing household-generated goods, but not household-generated services—an issue explained below in the section ‘Income, production and asset boundaries’8.

National accounts provide statistics and data beyond GDP that can help countries measure progress in broader terms. These other statistics relate to well-being and sustainability, but need more attention and use to fully realize their potential as indicators of ocean sustainability. The strong foundation provided by the SNA is due, in part, to its rich statistical setup and quadruple entry accounting system, with many internal consistency checks. The SNA includes production accounts (to measure how much producers make and sell); consumption and expenditure accounts (to measure how much households buy and consume); accumulation accounts and balance sheets (to measure the change in assets and their value); supply and use or input–output tables (to describe the interconnections of how goods and services flow through the economy); and guides for indexing changes through time.

The SNA already partially includes the ocean economy. In concept, the SNA includes a national balance sheet that includes ‘non-produced’ assets, which is where many ocean natural assets, such as fish stocks and coral reefs, are supposed to be recorded. Changes in the balance sheets provide a measure of the change in wealth, a key sustainability metric20,21. The supply and use tables provide the foundation for input–output tables that show how sectors in the economy are interconnected. These tables have a similar structure to ecosystem models such as Atlantis and EcoPath/EcoSim22,23,24, which can facilitate integrated assessment of environmental and economic change. Ocean production, such as shipping, and ocean capital investment, such as port expansion, are also within the scope of national accounts. The production, expenditure and income accounts all balance so that GDP and ‘gross domestic income’ are equal—though this measure of income differs from what economists believe is a proper measure of real income17,25,26.

The SNA provides for alternative sectoral-based summaries called ‘satellite’ accounts. These allow for a subset of indicators focused around a particular purpose, including the ocean economy. Countries such as Portugal (https://go.nature.com/3fSAecD) and Canada (https://go.nature.com/3eS0xyi) have physical and monetary satellite accounts for the ocean. The Netherlands has a physical account (https://go.nature.com/2WIyrPU). Australia has produced an experimental account for the Great Barrier Reef under the SEEA–Experimental Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA–EEA) framework (https://go.nature.com/3hmXujq). Other countries, for example, Ghana, produce a headline measure of fishery GDP. The United States, Norway, China and many other countries provide substantial information on the economic activity related to the ocean in their national accounts.

The opportunities for using national accounting to assess progress on blue development cannot be divorced from how the information in the accounts is communicated. Data from national accounts are most commonly communicated as a single GDP-like figure. However, there are also often summaries of high-level industrial output categories and household consumption contained in a static report or sometimes an excel spreadsheet. A few countries provide database-style access to a series of such tables. Implicit in these reports are the aggregation rules, categorization, boundaries, topics where data are missing and decisions about what information is relevant for decision makers.

Challenges for national accounting for the ocean

To apply SNA concepts requires passing through a cascade of filters (Fig. 2). It is important to identify which filters create challenges and lead good ideas—like those in the design of national accounts—to fall short.

The broadest filter relates to whether accounting-style data answer the question being asked. Measures and statistics help achieve goals, but they do not set goals. There are important questions about ocean sustainability that no amount of data or measurement will answer; for example, how much better off society should leave the next generation or what mechanism to use to reallocate income. Yet, measuring the condition of the ocean and ocean economy is important for conversations about what the goals are and assessing progress. It can also help society avoid outcomes that are undesirable, even in the absence of agreement on the desired outcome.

The next filter relates to concepts and theory contained within the system of national accounts. There are many questions national accounts can help answer. But it is imperative to ask the right questions. The questions involve (1) well-being and its distribution (real income)17,18,25; (2) future opportunities for sustainability (wealth)20,21,27,28; and (3) resource production or mobilization (means). Concepts, theory and data to address each of these questions exist. However, national statistics offices do not hold all of these data. Realizing ocean accounts requires extending existing intergovernmental collaboration beyond banks and finance ministries to other government, multinational and non-government organizations—especially those with scientific expertise about the ocean.

The current SNA structure, the third filter, imposes a certain scope or set of boundaries on national accounts. This filter, along with the previous filter, helps answer the question of whether the SNA–SEEA framework is sufficient. The general framework is sound, but the current boundaries are too narrow to address sustainability of the ocean economy or economy in general. Indeed, boundaries have been a challenge from the early days of national accounts16. Because boundaries determine what ocean components are considered or excluded, and to what extent, they are far more than a technicality. Boundaries are something that accounting, economics and physical science cannot address in a disciplinary fashion. Three types of boundaries need to be altered to allow fit-for-purpose subsets of information: the income boundary (and by extension the asset and production boundaries), the sectoral boundary and the physical boundary.

The final filter, convention and current practice, helps answer the question of whether the actual compilation process of national accounts under the SNA is sufficient. Here, we use convention to refer to what is generally done in practice. It leads to three areas that need closer attention. First, when resources for collecting data and producing statistics are constrained, national accountants and statisticians must prioritize certain parts of the national accounts, which influences what boundaries are delineated. This can lead to incomplete development of the statistics that address blue economy goals (2) and (3)—especially when questions are only asked about GDP. Second, which summary statistics are created and communicated is the result of an interaction between the formal structure of the SNA and convention. The SNA encourages a net domestic product and net domestic income summary that would better reflect a change in wealth8, but net rather than gross summary indicators of income and production are far less-frequently provided and discussed. Third, the way the national accounts data are aggregated and communicated needs modernization. Stiglitz et al.18 called for a dashboard presenting multiple summary indicators to provide a broader picture of well-being. New technology enables the realization of the Stiglitz et al. recommendation for interactive digital dashboards that can help address boundary and aggregation challenges through their flexibility. We argue that developing dashboards for the ocean economy is crucial for blue economic development and for increasing the saliency of existing ocean accounts (for example, Portugal, the Great Barrier Reef and so on) and non-GDP statistics for decision makers.

Determining what is in scope

The overall bounds of the national accounts need to be broad enough in concept and practice to enable any subset to be created and compared to the rest of the economy. The ability to create subsets of data along multiple boundaries is critical for ocean accounts because the current accounting boundaries do not encapsulate all the information needed to track changes in comprehensive wealth29,30 to measure welfare and sustainability (see blue economy objectives 2 and 3 in Fig. 1). Furthermore, not all the information needed for ocean partitions of the accounts is currently present. We identify three main challenges to delimit scope, regarding conceptual, physical and sectoral boundaries.

Income, production and asset boundaries

A first boundary challenge is to decide what counts as income, for whom, and how it is distributed. The income boundary is interconnected with the production and asset boundaries in the SNA. The income boundary is challenging to define for national accounts broadly14. The ocean provides many goods and services, and some enter the market while others do not. Importantly, the SNA includes goods—but not services—produced by households for their own use, and admits this decision is a compromise8. This is a problem for three reasons. First, some non-market services are included in the SNA, for example, owner-occupied housing, while other non-market services are excluded altogether, for example, carbon storage and leisure. Certainly, the state of the ocean influences the value of ocean-front property, which has a large impact on the distribution of imputed value for owner-occupied housing. Second, the SNA is not fully implemented in practice. Many subsistence ocean goods which should be included, per the agreed-upon accounting standards, are not. Fish caught for household consumption, for example, should be accounted for according to the SNA, but many national statistics offices do not have capacity to measure subsistence production of fish. Third, SNA guidance and practice interact to make it challenging to account for services with zero marginal cost even as economies become more dependent on them. For example, ocean recreation and contributions to mental health suffer from the same misrepresentation as streaming music services and search engines31. Nonetheless, the notion that ocean assets provide services that are just too hard to value is not credible, and substantial progress has been made in developing methods that are as robust as those used to measure other parts of the economy32,33,34,35.

National statistics offices need to account for the institutional realities of a wider range of goods and services important to well-being than are currently included. Some are formally included within the SNA, but go unmeasured, others are formally excluded from the SNA. Even for relatively well-established income that corresponds to market-linked production, there are further challenges. The SNA boundaries related to the ocean appear to exist in part because of misunderstandings of ocean governance or because of disputes over what counts as governance and ‘economic ownership’. SNA guidelines require that there be an economic owner that can benefit from a stock, in order for that stock to be considered an asset. Ocean governance structures create economic owners—often governments who manage their maritime zones. For example, Part V of the Convention on the Law of the Sea36 moves many ocean biological assets inside the SNA boundaries through establishment of Exclusive Economic Zones. Yet, convention is to assume a lack of governance and leave biological ocean assets off national balance sheets. SNA section 1.43 on the production boundary explicitly excludes the growth of fish stocks “on the high seas” outside of international quotas, while including growth of farmed fish stocks. However, for the asset boundary, the 2008 SNA (section 1.46) says that any wild animal for which an institutional unit is “exercising effective ownership rights” over should be included in the balance sheet. Specifically, the SNA states, “Natural resources such as land… uncultivated forests or other vegetation and wild animals are included in the balance sheet provided that institutional units are exercising effective ownership rights over them, that is, are actually in a position to be able to benefit from them. Assets need not be privately owned, and could be owned by government units exercising ownership rights on behalf of entire communities. Thus, many environmental assets are included within the SNA”. Most fish are caught within Exclusive Economic Zones and are managed by quotas, limited access or other governance structures that countries collectively benefit from. Yet, most countries treat fish stocks as if they are unmanaged high-seas stocks. Only New Zealand has considered moving wild fish populations onto national balance sheets, and this was facilitated by the tradeable quota programme that provides price information without imputation37. It is not just fish that a government can ‘own’ on behalf of communities. Krutilla38 argues that people’s ‘scenic wonder’ is an economic benefit and the destruction of natural wonders reduces real income. Certainly, reefs and mangroves have such qualities and governments often ‘exercise effective ownership’ and are in a position to benefit from resources in terms of factors of production for their citizens.

Once these boundary issues are sorted out, it is relatively straightforward to account for changes in ocean capital. Hulten39 argues that the relevant question for national capital asset accounting is what to do rather than how to do it. The same seems true for other sections of national accounts. Many of the ‘how’ questions have been asked and answered in the literature already. For example, in a case where the boundary issues were relatively easy to resolve, Yun et al.40 showed how ecosystem-based management increases the wealth stored in Baltic Sea fisheries by about 30%. A regular production of accounts, rather than one-offs, will provide the necessary information to learn from past decisions.

The physical boundary

The ocean is often a geographic boundary for a country. Coastal countries have territorial waters, continental shelves and Exclusive Economic Zones, and assets and transactions occurring in these regions need to be included in the broad account.

The ocean economy is usually a subset of the broader economy and also rarely constrained to the water. The ocean, its contents, and its attributes are not static. Even with defined geographic boundaries and clear concepts of ownership and inclusion, null- or double-counting of assets can occur, meaning that the sum of country-level national accounts does not reliably characterize the regional, let alone global, ocean economy. Further, where institutional boundaries dissect physical boundaries, the value of ocean natural resources may hinge on the choice of the economic boundary41. These issues raise questions about how accounts should record activities beyond national boundaries as well as how far inland the boundary of the ocean economy should extend.

The sectoral boundary

Determining which sectors to include in the ocean economy is another challenge. Portugal, for example, includes line items for leather goods and legal services in their satellite account for the sea; a far greater level of detail than existing ocean accounting efforts employ, and one that bends credulity. Shipping, tourism and other activities only tangentially related to the biological condition of the ocean tend to dominate ocean GDP for the countries that compute such a measure. Another industry often included in marine satellite accounts is insurance against storm damage. Expenditures made to insure one’s self against the ocean are hardly value-added from the ocean.

Summary statistics and communication

Existing concepts and theory for measuring the ocean economy are close to what is needed for blue growth, and there is no need for wholly new frameworks42. However, conventions associated with the actual compilation need to change, including issues associated with aggregation and prioritization. Another reasonable critique is that use of details within the national accounts is insufficient for measuring the progress of a sustainable ocean economy, and there is too much focus on aggregates constructed for other purposes. This is primarily a communication challenge that requires asking the right questions and making sure that data from national accounts are accessible so that the right questions can be answered easily.

Asking questions beyond GDP

The ‘P’ in GDP stands for production of means or outputs, but mobilization of means is more accurate. GDP does not distinguish innovation and creation from drawing down on already-produced, or endowed, reserve of capital. This is an important distinction in a frontier economy like the ocean, where fish and minerals appear to be endowments waiting to be harvested. GDP focuses on the fact that no human inputs were needed to create them, but does not account for the opportunity cost of using them today when they may be more valuable in the future. It also does not provide information about the purpose for which means that support consumption are mobilized or who gets access to them. As such, calculating the ocean GDP is not the solution to the problem of measuring the sustainability of the ocean economy. Most of what would show up in an ocean GDP is probably already measured in national accounts and in national GDP. Creating an ocean GDP would not modify headline GDP. As a motivation for ocean conservation, GDP is a problematic non-sequitur. It is the wrong tool for measuring ocean sustainability because biodiversity, for example, has little bearing on ocean GDP, which mostly reflects shipping and other coastal industrial processes. There are three obvious directions to go ‘beyond GDP’18 to address blue development goals (2) and (3) (Fig. 1).

First, national accounts need to provide information on changes in future opportunities afforded by the ocean. Accumulation accounts and balance sheets track wealth—a current assessment of future opportunities. These have been part of the SNA since the early 1990s. The comprehensive and inclusive wealth initiatives that track balance sheet changes29,30 provide a window into the information that balance sheets a broad cross-section of assets could provide. The barrier to moving to balance sheets with substantial coverage of oceans assets is not valuation beyond the market boundary. Fenichel et al.34 provide a theory and method for measuring capital not traded in markets that parallels market prices as one solution. Still, most national balance sheets are incomplete with respect to natural resources and ocean assets. Yet, asking countries to complete balance sheets is not a new request; it is something most countries have already agreed to do. A refocusing of national accounts around the plurality of complete balance sheets rather than singularity of a GDP indicator would catalyse the realization of these agreements and advance efforts to develop a sustainable ocean economy. Importantly, the total value of the ocean balance sheet has little meaning, only the changes matter27, which is why regular production on annual or quarterly intervals is important as are appropriate index numbers43,44.

Second, measures of ocean-related real income and welfare are necessary. Jorgenson and Slesnick17 show how reasonable measures of social well-being or real income45 can be computed from information mostly already in national accounts, also addressing distribution. However, ocean accounts require a greater focus on non-market goods and services because many ocean services are non-market; for example, recreation. While intermediate services from the ocean, like growth of fish stocks, may not enter directly into production and consumption accounts, they can affect the value of ocean capital and the change in the balance sheet. Furthermore, defensive expenditures made to protect ourselves from the ocean probably need to be deducted from production and income statistics25,46, but determining exactly what is a defensive expenditure can be challenging. Expenditures on marine conservation, such as conservation of mangroves, seagrasses and coral reefs, should be treated as investment in capital, not current production.

Third, national accounts are a treasure trove of data, but greater data integration within countries and from international data sources is necessary for ocean accounts. Finnoff and Tschirhart47 and Banerjee et al.48 show how supply and use economic data could be combined with ecological data, often already in a similar format, for integrated assessments of the ocean and ocean economy. Data management is a challenge because of the need to integrate public data with private, sensitive data, and because some data sets, especially physical data sets, are massive49. It is important to merge these data sources because assessing the state of the ocean and the ocean economy requires having measures in physical and monetary terms. Having both provides the lenses for stakeholders with different perspectives to see the same world. This plural approach to measurement is also about communication—a precursor to inclusive decision making. However, few countries produce physical and monetary measures for the ocean, and the few that do seldom connect the two.

Aligning questions with answers

Developing a sustainable ocean economy means changing the questions asked and the paradigm for reporting the answers. There may be disagreements on the appropriate sectoral or physical boundaries, or even what counts as income or wealth, for the ocean economy. However, these disagreements may stem from different questions that require different boundaries, different summaries, or specific details. No report can answer all questions, but there is value in a commonly agreed-upon set of facts to draw upon and in placing them in a complementary, rather than competing, context within a structured family of indicators. Furthermore, ocean accounting tools need to help decision makers guide the ocean economy in ways that are robust to disputed boundaries, or at least provide the information to understand the trade-offs inherent in defining a particular boundary. Keith et al.50 show how this can be done with an example of the tall, wet forests of the Central Highlands in Victoria, Australia.

Digital dashboards enable information about multiple indicators to respond rapidly to user-specified shifts in boundaries and for users to analyse which boundaries matter for indicators, decisions and segments of the ocean economy or society. Digital dashboards also enable drilling down and disaggregating. Linking dashboards to the broader economy, physical state of the ocean, and context enables users to rapidly adjust connections so that they can evaluate the state of the ocean and ocean economy from different perspectives. This helps competing interests appreciate alternative views while maintaining a commonly agreed-upon set of facts. Conversely, static reports or spreadsheets can often only accommodate a single boundary specification—and therefore, a single point of view. This limitation has placed key boundary decisions in the hands of national statisticians, who may be disconnected from policy decision making. Dashboarding technology allows national statisticians and other analysts to focus on data and algorithms rather than final numbers and enables decision makers to choose fit-to-purpose boundaries. Dashboards can facilitate public access and policy dialogue.

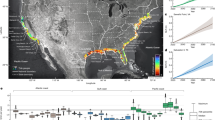

It is time to take the figurative recommendation for dashboards of Stiglitz et al.18 literally and use interactive dashboards that enable fit-to-purpose aggregation and sectoral and location weighting decisions to discuss ocean accounts. The United States has begun producing such dashboards; https://go.nature.com/2ZOTn9M. As a test, we produced a dashboard in about six weeks using off-the-shelf enterprise software and publicly available Norwegian data; https://go.nature.com/39gvD1F (Fig. 3). The tools for building these dashboards are increasingly available, and building basic dashboards requires only slightly greater technical proficiency than a spreadsheet. However, dashboards can fundamentally change the way questions are asked and stories are told.

The interactive version is available at https://go.nature.com/39gvD1F.

The flexibility of dashboards raises concerns about ‘cooking the books’. However, establishing ‘default settings’ or a set of required ‘filters’ for specific treaties or international reporting requirements can mitigate these concerns. Importantly, regularly produced indicators would still sit in established families of indicators—like GDP, change in wealth, or real income distribution—but what is included could be adjusted. Furthermore, dashboards could enable greater third-party exploration of decisions currently made deep inside statistical offices. Using somewhat standardized but poorly fit-to-purpose indicators to hold countries to account seems inferior to facilitating the statistical innovation that dashboards make possible (most countries producing ocean satellite accounts use slightly different boundaries and aggregation rules so they are not truly standardized).

Conclusions

No one wants to fly in a plane with a single instrument dial. Yet, a narrow focus on GDP implies that a single measure is deemed sufficient to discuss social and economic progress—this is no way to manage the ocean and its economy. Technological advances in digital dashboards can facilitate disaggregation of statistics covering a wide range of concerns. The great contribution of the national accounts in the twentieth century was the ability to summarize the human enterprise on a single sheet of paper (or short report) and to provide a measure of a performance measure in a time when there were no comprehensive indicators for the economy. This matched the twentieth century’s industrial push and the drive for economies of scale51. It also aligned with the need to mobilize substantial consumption opportunities to pull much of the world out of poverty, even in what we call rich countries today. The national accounts need to evolve to maintain structure while enabling customization of the dimensions included, for example whether to include seabed mining, marine legal services, reefs or recreational swimming. This is particularly true for ocean accounts. Modern data management and communication can, or will soon, be able to easily and quickly disaggregate data. For example, offering a dynamic dashboard where users can adjust the myriad boundaries of accounts and bring in additional information that is not part of conventional accounts. This tool puts equity weighting back into the hands of policy makers.

A modified and broader system of national accounts can be up to the task of providing a commonly agreed-upon set of facts that is helpful for ensuring a prosperous, inclusive and sustainable ocean economy. Many of the needed reforms are not unique to oceans, but can provide a dashboard for evaluating the performance of policy for all current or future sustainable development goals. Further, a substantial fraction of the areas needing reform are conventions and implementation rather than formal structures and standards, as these as not currently aligned. This points to working with the SNA, SEEA and satellite accounts to address the deficit of convention, implementation and communication. A sustainable ocean economic measurement system needs country-level leadership to enact reforms and develop national accounting strategies, including funding and prioritization for statistics and information. It is not sufficient to get explicit international agreement to consider natural and ocean capital, because existing agreements do it already. Rather, countries need to do the hard work of realizing these agreements. Fortunately, this is starting to happen. Over eighteen countries have committed to producing ocean accounts, and a growing number are joining global collaboration efforts to coordinate the development of ocean accounts aligned with the SNA and SEEA (www.oceanaccounts.org).

Changes in wealth, distribution of welfare, production and the interconnections within the ocean economy are all important. A single aggregate cannot summarize them all effectively, but there is no shortage of potential summary statistics—the challenge is organizing them to be useful52. Services produced and consumed outside the market; for example, climate regulation, ocean-based leisure and coastal erosion, are the targets of policy. For the accounts to remain relevant, they must provide a measure of outcomes for people, not just means mobilized. The income accounts and balance sheets must be developed to completion for the whole economy, and a focus on oceans can provide the pathway to do so. Importantly, the key is to develop structured families of summary statistics within the SNA–SEEA framework rather than a plethora of new metrics53. Perhaps the greatest legacy of securing a sustainable ocean economy is that developing measurement to guide sustainable ocean development can light the way for measurement to a sustainable global economy.

References

Colgan, C. S. Measurement of the ocean economy from national income accounts to the sustainable blue economy. J. Ocean Coast. Econ. 2, 12 (2016).

Eikeset, A. M. et al. What is blue growth? The semantics of “Sustainable Development” of marine environments. Mar. Policy 87, 177–179 (2018).

Report on the Blue Growth Strategy Towards More Sustainable Growth and Jobs in The Blue Economy Report no. SWD(2017) 128 final (European Commission, 2017).

European Union DG of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Joint Research Centre The 2018 Annual Economic Report on the EU Blue Economy (European Union, 2018).

The Blue Economy: Growth, Opportunity and a Sustainable Ocean Economy (The Economist Intelligence Unit, 2015).

Golden, J. S. et al. Making sure the blue economy is green. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0017 (2017).

Posner, S. M. et al. Boundary spanning among research and policy communities to address the emerging industrial revolution in the ocean. Environ. Sci. Policy 104, 73–81 (2020).

System of National Accounts 2008 (European Commission, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, United Nations, World Bank, 2009).

United Nations, European Union, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, The World Bank System of Environmental Economic Accounting 2012—Central Framework (United Nations, 2014).

Hein, L. et al. Progress in natural capital accounting for ecosystems. Science 367, 514–515 (2020).

Kuznets, S. Modern economic growth: findings and reflections. Am. Econ. Rev. 63, 247–258 (1973).

Fenichel, E. P. et al. National Accounting for the Ocean and Ocean Economy (World Resources Institute, 2020); https://go.nature.com/30W16Cm

United Nations, European Union, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, The World Bank System of Environmental Economic Accounting 2012—Experimental Ecosystem Accounting (United Nations, 2014).

Landefeld, J. S. GDP: one of the great inventions of the 20th century. Surv. Curr. Bus. 80, 6–9 (2000).

Jorgenson, D. W. Production and welfare: progress in economic measurement. J. Econ. Lit. 56, 867–919 (2018).

Coyle, D. GDP: A Brief but Affectionate History-Revised and Expanded Edition (Princeton Univ. Press, 2015).

Jorgenson, D. W. & Slesnick, D. T. in Measuring Economic Sustainability and Progress (eds Jorgenson, D. W. et al.) 43–88 (Univ. Chicago Press, 2014).

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A. & Fitoussi, J.-P. Mis-measuring our lives: why GDP doesn’t add up, the report by the Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress (The New Press, 2010).

Fitoussi, J.-P. & Durand, M. Beyond GDP Measuring What Counts for Economic and Social Performance: Measuring What Counts for Economic and Social Performance (OECD Publishing, 2018).

Matson, P., Clark, W. C. & Andersson, K. Pursuing Sustainability: A Guide to the Science and Practice (Princeton Univ. Press, 2016).

Arrow, K. et al. Are we consuming too much? J. Econ. Perspect. 18, 147–172 (2004).

Audzijonyte, A., Gorton, R., Kaplan, I. & Fulton, E. A. Atlantis User’s Guide Part I: General Overview, Physics & Ecology (CSIRO, 2018).

Collie, J. S. et al. Ecosystem models for fisheries management: finding the sweet spot. Fish Fish. 17, 101–125 (2016).

Steenbeek, J. et al. Ecopath with Ecosim as a model-building toolbox: source code capabilities, extensions, and variations. Ecol. Model. 319, 178–189 (2016).

Nordhaus, W. D. & Tobin, J. in Economic Research: Retrospect and Prospect Vol. 5 (eds Nordhaus, W. D. & Tobin, J.) 1–80 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1972).

Heal, G. Valuing the Future: Economic Theory and Sustainability (Columbia Univ. Press, 1998).

Dasgupta, P. Human Well-Being and the Natural Environment (Oxford Univ. Press, 2001).

Hamilton, K. & Clemens, M. Genuine savings rates in developing countries. World Bank Econ. Rev. 13, 333–356 (1999).

Lange, G.-M., Wodon, Q. & Carey, K. The Changing Wealth of Nations 2018: Building a Sustainable Future (World Bank, 2018).

Managi, S. & Kumar, P. Inclusive Wealth Report 2018 Measuring Progress Towards Sustainability (Routledge, UNEP, and Urban Institute, 2018).

Brynjolfsson, E., Diewert, W. E., Eggers, F., Fox, K. J. & Gannamaneni, A. The digital economy, GDP and consumer welfare: Theory and evidence. In ESCoE Conference on Economic Measurement, Bank of England; 2018 16–17 (Bank of England, 2018).

Barbier, E. B. Pricing nature. Annu. Rev. Res. Econ. 3, 337–353 (2011).

Mendelsohn, R. & Olmstead, S. The economic valuation of environmental amenities and disamenities: methods and applications. Annu. Rev. Env. Res. 34, 325–347 (2009).

Fenichel, E. P., Abbott, J. K. & Yun, S. D. in Handbook of Environmental Economics Vol. 4 (eds Smith, V. K. et al.) 85–142 (North Holland, 2018).

Phaneuf, D. J. & Requate, T. A Course in Environmental Economics Theory, Policy, and Practice (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2017).

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (United Nations, 1982).

Hammond, K. Statistical benefits of individual transferable quotas for valuing natural capital 2005. In EASDI Conference 2005 (Stats NZ, 2005); https://go.nature.com/30RNpo5

Krutilla, J. V. Conservation reconsidered. Am. Econ. Rev. 57, 777–786 (1967).

Hulten, C. R. in A New Architecture for the U.S. National Accounts (eds Jorgenson, D. W. et al.) Ch. 5 (Univ. Chicago Press, 2006).

Yun, S. D., Hutniczak, B., Abbott, J. K. & Fenichel, E. P. Ecosystem based management and the wealth of ecosystems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 6539–6544 (2017).

Addicott, E. T. & Fenichel, E. P. Spatial aggregation and the value of natural capital. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 95, 118–132 (2019).

Guerry, A. D. et al. Natural capital and ecosystem services informing decisions: from promise to practice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7348–7355 (2015).

Fenichel, E. P. & Obst, C. Discussion paper 5.3: a framework for the valuation of ecosystem assets. In Expert Meeting on Advancing the Measurement of Ecosystem Services for Ecosystem Accounting (SEEA, 2019); https://go.nature.com/2EhThPJ

Fenichel, E. P. et al. Wealth reallocation and sustainability under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 237–244 (2016).

Hicks, J. R. Value and Capital: An Inquiry into Some Fundamental Principles of Economic Theory (Oxford Univ. Press, 1939).

Muller, N. Z., Mendelsohn, R. O. & Nordhaus, W. D. Environmental accounting: methods with an application to the United States economy. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 1–30 (2011).

Finnoff, D. & Tschirhart, J. Harvesting in an eight-species ecosystem. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 45, 589–611 (2003).

Banerjee, O., Cicowiez, M., Vargas, R. & Horridge, M. The SEEA-Based Integrated Economic-Environmental Modelling Framework: an illustration with Guatemala’s forest and fuelwood sector. Environ. Resour. Econ. 72, 539–558 (2019).

Esch, T. et al. Exploiting big earth data from space–first experiences with the timescan processing chain. Big Earth Data 2, 36–55 (2018).

Keith, H., Vardon, M., Stein, J. A., Stein, J. L. & Lindenmayer, D. Ecosystem accounts define explicit and spatial trade-offs for managing natural resources. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1683–1692 (2017).

Maler, K.-G. National accounts and environmental resources. Environ. Resour. Econ. 1, 1–15 (1991).

Fleurbaey, M. & Blanchet, D. Beyond GDP Measuring Welfare and Assessing Sustainability (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Hoekstra, R. Replacing GDP by 2030: Towards a Common Language for the Well-Being and Sustainability Community (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2019).

Acknowledgements

Support was provided by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy. This research is adapted from a Blue Paper commissioned by the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy entitled ‘National Accounting for the Ocean and Ocean Economy’. E.P.F. and E.T.A. were additionally supported by the Knobloch Family Foundation. The views expressed in this paper are the authors’ views, and they do not represent the views of their respective organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.P.F. lead the project and writing, E.T.A. developed the dashboard in Fig. 3, and all authors contributed to writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fenichel, E.P., Addicott, E.T., Grimsrud, K.M. et al. Modifying national accounts for sustainable ocean development. Nat Sustain 3, 889–895 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0592-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0592-8

This article is cited by

-

Five priorities for a sustainable ocean economy

Nature (2020)