Abstract

The Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil has emerged as the leading sustainability certification system to tackle socioenvironmental issues associated with the oil palm industry. However, the effectiveness of certification by the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil in achieving its socioeconomic objectives remains uncertain. We evaluate the impact of certification on village-level well-being across Indonesia by applying counterfactual analysis to multidimensional government poverty data. We compare poverty across 36,311 villages between 2000 and 2018, tracking changes from before oil palm plantations were first established to several years after plantations were certified. Certification was associated with reduced poverty in villages with primarily market-based livelihoods, but not in those in which subsistence livelihoods were dominant before switching to oil palm. We highlight the importance of baseline village livelihood systems in shaping local impacts of agricultural certification and assert that oil palm certification in certain village contexts may require additional resources to ensure socioeconomic objectives are realized.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Key datasets used to conduct our analysis are publicly available from the cited references (forest cover data available from https://glad.umd.edu/dataset/primary-forest-cover-loss-indonesia-2000-2012 and https://earthenginepartners.appspot.com/science-2013-global-forest/download_v1.5.html and socioeconomic data from https://mikrodata.bps.go.id/mikrodata/index.php/catalog/PODES). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Meijaard, E. et al. Oil Palm and Biodiversity—A Situation Analysis (IUCN Oil Palm Task Force, 2018).

Tree Crop Estate Statistics of Indonesia 2017–2019 (Directorate General of Estate Crops Indonesia, 2019).

Sayer, J., Ghazoul, J., Nelson, P. & Boedhihartono, A. K. Oil palm expansion transforms tropical landscapes and livelihoods. Glob. Food Security 1, 114–119 (2012).

Susanti, A. & Maryudi, A. Development narratives, notions of forest crisis, and boom of oil palm plantations in Indonesia. For. Policy Econ. 73, 130–139 (2016).

Potter, L. New transmigration ‘paradigm’ in Indonesia: examples from Kalimantan. Asia Pac. Viewp. 53, 272–287 (2012).

Pye, O. Commodifying sustainability: development, nature and politics in the palm oil industry. World Dev. 121, 218–228 (2019).

McCarthy, J. F. Processes of inclusion and adverse incorporation: oil palm and agrarian change in Sumatra, Indonesia. J. Peasant Stud. 37, 821–850 (2010).

Colchester, M. Palm Oil and Indigenous Peoples in South East Asia (Forest Peoples Programme, 2011).

Li, T. M. Intergenerational displacement in Indonesia’s oil palm plantation zone. J. Peasant Stud. 44, 1158–1176 (2017).

Gaveau, D. L. et al. Rise and fall of forest loss and industrial plantations in Borneo (2000–2017). Conserv. Lett. 12, e12622 (2019).

White, B. N. F. Gendered experiences of dispossession: oil palm expansion in a Dayak Hibun community in West Kalimantan. J. Peasant Stud. 39, 995–1016 (2012).

Carlson, K. M. et al. Influence of watershed–climate interactions on stream temperature, sediment yield, and metabolism along a land use intensity gradient in Indonesian Borneo. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 119, 1110–1128 (2014).

Merten, J. et al. Water scarcity and oil palm expansion: social views and environmental processes. Ecol. Soc. 21, 5 (2016).

Luke, S. H. et al. The effects of catchment and riparian forest quality on stream environmental conditions across a tropical rainforest and oil palm landscape in Malaysian Borneo. Ecohydrology 10, e1827 (2017).

Wells, J. A. et al. Rising floodwaters: mapping impacts and perceptions of flooding in Borneo. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 064016 (2016).

Carlson, K. M. et al. Carbon emissions from forest conversion by Kalimantan oil palm plantations. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 283–287 (2013).

Marlier, M. E. et al. Fire emissions and regional air quality impacts from fires in oil palm, timber, and logging concessions in Indonesia. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 085005 (2015).

Tan-Soo, J. S. & Pattanayak, S. K. Seeking natural capital projects: forest fires, haze, and early-life exposure in Indonesia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 5239–5245 (2019).

Santika, T. et al. Interannual climate variation, land type and village livelihood effects on fires in Kalimantan, Indonesia. Glob. Environ. Change 64, 102129 (2020).

Principles & Criteria Certification for the Production of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO, 2018).

Impact Report (RSPO, 2019); https://rspo.org/about/impacts

RSPO Jurisdictional Approach (RSPO, 2019).

Ruysschaert, D. & Salles, D. Towards global voluntary standards: euestioning the effectiveness in attaining conservation goals: the case of the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO). Ecol. Econ. 107, 438–446 (2014).

De Man, R. & German, L. Certifying the sustainability of biofuels: promise and reality. Energy Policy 109, 871–883 (2017).

Cattau, M. E., Marlier, M. E. & DeFries, R. Effectiveness of Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) for reducing fires on oil palm concessions in Indonesia from 2012 to 2015. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 105007 (2016).

Carlson, K. M. et al. Effect of oil palm sustainability certification on deforestation and fire in Indonesia. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 121–126 (2018).

Morgans, C. L. et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of palm oil certification in delivering multiple sustainability objectives. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 064032 (2018).

Furumo, P. R., Rueda, X., Rodríguez, J. S. & Ramos, I. K. P. Field evidence for positive certification outcomes on oil palm smallholder management practices in Colombia. J. Clean. Prod. 245, 118891 (2019).

Heilmayr, R., Carlson, K. M. & Benedict, J. J. Deforestation spillovers from oil palm sustainability certification. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 075002 (2020).

Santika, T. et al. Does oil palm agriculture help alleviate poverty? A multidimensional counterfactual assessment of oil palm development in Indonesia. World Dev. 120, 105–117 (2019).

Santika, T. et al. Changing landscapes, livelihoods and village welfare in the context of oil palm development. Land Use Policy 87, 104073 (2019).

Jerneck, A. & Olsson, L. More than trees! Understanding the agroforestry adoption gap in subsistence agriculture: insights from narrative walks in Kenya. J. Rural Stud. 32, 114–125 (2013).

Chan, K. M. et al. in Natural Capital: Theory and Practice of Mapping Ecosystem Services (eds Kareiva, P. et al.) 206–228 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

Scoones, I. Sustainable Rural Livelihoods: A Framework for Analysis Working Paper 72 (Brighton Institute of Development Studies, 1998).

Liu, Y. & Xu, Y. A geographic identification of multidimensional poverty in rural China under the framework of sustainable livelihoods analysis. Appl. Geogr. 73, 62–76 (2016).

Sen, A. in Poverty and Inequality (eds Grusky, D. B. & Kanbur, R.) 30–46 (Stanford Univ. Press, 2006).

Village Potential Statistics (PODES) 2000, 2003, 2005, 2008, 2014, and 2018 (Bureau of Statistics Indonesia, 2019).

Setiawan, E. N., Maryudi, A., Purwanto, R. H. & Lele, G. Opposing interests in the legalization of non-procedural forest conversion to oil palm in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Land Use Policy 58, 472–481 (2016).

Gupta, J., Pouw, N. R. & Ros-Tonen, M. A. Towards an elaborated theory of inclusive development. Eur. J. Dev. Res. 27, 541–559 (2015).

Dauvergne, P. & Neville, K. J. Forests, food, and fuel in the tropics: the uneven social and ecological consequences of the emerging political economy of biofuels. J. Peasant Stud. 37, 631–660 (2010).

Budidarsono, S., Susanti, A. & Zoomers, A. in Biofuels: Economy, Environment and Sustainability (ed. Fang, Z.) 173–193 (Intech, 2013).

Schoneveld, G. C. et al. Certification, good agricultural practice and smallholder heterogeneity: differentiated pathways for resolving compliance gaps in the Indonesian oil palm sector. Glob. Environ. Change 57, 101933 (2019).

Gaveau, D. L. A. et al. Overlapping land claims limit the use of satellites to monitor no-deforestation commitments and no-burning compliance. Conserv. Lett. 10, 257–264 (2017).

Jelsma, I., Schoneveld, G. C., Zoomers, A. & Van Westen, A. C. M. Unpacking Indonesia’s independent oil palm smallholders: an actor-disaggregated approach to identifying environmental and social performance challenges. Land Use Policy 69, 281–297 (2017).

Waldman, K. B. & Kerr, J. M. Limitations of certification and supply chain standards for environmental protection in commodity crop production. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 6, 429–449 (2014).

Klasen, S. et al. Economic and ecological trade-offs of agricultural specialization at different spatial scales. Ecol. Econ. 122, 111–120 (2016).

Dislich, C. et al. A review of the ecosystem functions in oil palm plantations, using forests as a reference system. Biol. Rev. 92, 1539–1569 (2017).

Margono, B. A., Potapov, P. V., Turubanova, S., Stolle, F. & Hansen, M. C. Primary forest cover loss in Indonesia over 2000–2012. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 730–735 (2014).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Bergamini, N. et al. Indicators of Resilience in Socio-ecological Production Landscapes (SEPLs) (UNU-IAS, 2013).

Dale, V. H. et al. Indicators for assessing socioeconomic sustainability of bioenergy systems: a short list of practical measures. Ecol. Indic. 26, 87–102 (2013).

Miteva, D. A., Loucks, C. J. & Pattanayak, S. K. Social and environmental impacts of forest management certification in Indonesia. PLoS ONE 10, e0129675 (2015).

Lee, J. S. H., Miteva, D. A., Carlson, K. M., Heilmayr, R. & Saif, O. Does oil palm certification create trade-offs between environment and development in Indonesia? Environ. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abc279 (2020).

Alkire, S., Chatterjee, M., Conconi, A., Seth, S. & Vaz, A. Global Multidimensional Poverty Index 2014 OPHI Briefing 21 (Univ. Oxford, 2014).

Gönner, C. et al. Capturing Nested Spheres of Poverty: A Model for Multidimensional Poverty Analysis and Monitoring Occasional Paper No. 46 (CIFOR, 2007).

Digital Map of Local Statistical Area 2014 (Bureau of Statistics Indonesia, 2014).

Lee, J. S. H., Ghazoul, J., Obidzinski, K. & Koh, L. P. Oil palm smallholder yields and incomes constrained by harvesting practices and type of smallholder management in Indonesia. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 34, 501–513 (2014).

Gatto, M., Wollni, M., Asnawi, R. & Qaim, M. Oil palm boom, contract farming, and rural economic development: village-level evidence from Indonesia. World Dev. 95, 127–140 (2017).

Ridgeway, G. gbm: Generalized Boosted Regression Models. R package version 2.1.1 (2015).

Dehejia, R. H. & Wahba, S. Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Rev. Econ. Stat. 84, 151–161 (2002).

Austin, P. C. Optimal caliper widths for propensity‐score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm. Stat. 10, 150–161 (2011).

Sekhon, J. S. matching: Multivariate and Propensity Score Matching with Balance Optimization. R package version 4.9-2 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil for sharing concession data. This study was supported by the Arcus Foundation, the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Environmental Decisions Discovery programme, the Darwin Initiative and University of Kent Global Challenges Impact Fund. M.J.S. was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Research Leadership Award. K.M.C. acknowledges funding from the NASA New (Early Career) Investigator Program in Earth Science (NNX16AI20G) and the US Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, including Hatch Project HAW01136-H and McIntire Stennis Project HAW01146-M, managed by the College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources. F.A.V.S.J. has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 grant agreement No. 755956 (CONHUB).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.S., M.J.S., E.M. and K.A.W. conceived the idea. T.S. designed the study, processed the socioeconomic and environmental data and performed the analyses. M.J.S. coordinated the project and obtained funding with E.M. and K.A.W. K.M.C. and H.G. provided the concessions data. E.A.L., F.A.V.S.J., C.L.M. and M.A. assisted with the socioeconomic and environmental datasets. T.S. and M.J.S. led the manuscript, which was critically reviewed and edited by the other authors. All authors contributed to the interpretation of analyses and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

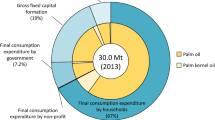

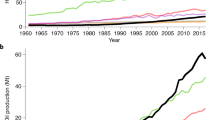

Extended Data Fig. 1 Total plantation area for key agricultural commodities across Indonesia and types of ownerships.

(a) Bar chart representing the total plantation area in 2019 for key agricultural commodities across Indonesia, and pie chart (above the bar) representing the proportion of different type of producer for each commodity, including smallholders, state or public-run companies, and private companies. (b) The change in cultivation area of the top five commodities (oil palm, rubber, coconut, cocoa, and coffee) every five years between 1980 and 2019, by producer type. Data were obtained from the Directorate General of Estate Crops Indonesia (2019).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Detailed change in distribution of forest and oil palm plantations in Sumatra.

Detailed change in the distribution of natural forest and oil palm plantations every 9 years between 2000 and 2018 in three major oil palm regions in Sumatra. Oil palm plantations are grouped into three categories: (1) RSPO-certified plantations (CERT), (2) non-certified plantations within oil palm concessions (CONC), and (3) non-certified plantations outside known oil palm concessions (NCONC).

Extended Data Fig. 3 Detailed change in distribution of forest and oil palm plantations in Kalimantan.

Detailed change in the distribution of natural forest and oil palm plantations every 9 years between 2000 and 2018 in four oil palm regions in Kalimantan. Oil palm plantations are grouped into three categories: (1) RSPO-certified plantations (CERT), (2) non-certified plantations within oil palm concessions (CONC), and (3) non-certified plantations outside known oil palm concessions (NCONC).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Detailed change in distribution of forest and oil palm plantations in Papua.

Detailed change in the distribution of natural forest and oil palm plantations every 9 years between 2000 and 2018 in three oil palm regions in Papua. Oil palm plantations are grouped into three categories: (1) RSPO-certified plantations (CERT), (2) non-certified plantations within oil palm concessions (CONC), and (3) non-certified plantations outside known oil palm concessions (NCONC).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Latent and observed change in village primary land use (and the associated livelihoods) to oil palm certification.

(a) Latent change in village primary land use (and the associated livelihoods), from high natural forest cover, to agricultural lands, mixed plantations and shrubs, followed by industrial oil palm plantations (non-certified), then finally becoming RSPO-certified industrial plantations. (b) Observed change in village primary land use (and the associated livelihoods) to industrial oil palm plantations and certification based on land cover data and PODES censuses 2000, 2005, 2011, and 2018 (see Methods), aggregated across Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua. Percentage on the right hand side of each row represents the proportion of villages with the associated transition between 2000 and 2018.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Impacts of RSPO-certification on indicators of well-being by village primary livelihoods.

The impact of oil palm certification (transition from oil palm villages to certified plantation villages) on each indicator of well-being in villages with primary livelihoods: (a) subsistence production, and (b) market-based. Indicators of well-being were grouped to socioeconomic and socioecological dimensions. Socioeconomic indicators include housing conditions (POOR), access to electricity (ELCT), cooking fuel (COOK), and toilet facilities (TOLT), child malnutrition incidence (MLNT), distance to healthcare facility (HEAL), primary school (PSCH), and secondary school (SSCH), and access to cooperative scheme (COOP) and credit facilities (CRDT). Socioecological indicators include the prevalence of conflicts (CNFL), agricultural labourers (AGLB), small industries (SIND), suicide rates (SUIC), voluntary cleaning and maintenance (GTRY), water pollution (WPOL), air pollution (APOL), and floods and landslides (FLOD). Results were derived across 3 time periods and two islands (Sumatra and Kalimantan). N represents the number of villages used to derive the impact estimates for each well-being indicator. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. See Supplementary Table 1 for description of each well-being indicator.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Impacts of industrial oil palm plantation development on indicators of well-being by village primary livelihoods.

7The impact of industrial oil palm plantation development (transition from non oil palm villages to oil palm villages) on each indicator of well-being in villages with primary livelihoods: (a) subsistence production, and (b) market-based. Indicators of well-being were grouped to socioeconomic and socioecological dimensions. . Socioeconomic indicators include housing conditions (POOR), access to electricity (ELCT), cooking fuel (COOK), and toilet facilities (TOLT), child malnutrition incidence (MLNT), distance to healthcare facility (HEAL), primary school (PSCH), and secondary school (SSCH), and access to cooperative scheme (COOP) and credit facilities (CRDT). Socioecological indicators include the prevalence of conflicts (CNFL), agricultural labourers (AGLB), small industries (SIND), suicide rates (SUIC), voluntary cleaning and maintenance (GTRY), water pollution (WPOL), air pollution (APOL), and floods and landslides (FLOD). Results were derived across 11 time periods and three islands (Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua). N represents the number of villages used to derive the impact estimates for each well-being indicator. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. See Supplementary Table 1 for description of each well-being indicator.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Impact of oil palm plantation development and certification on well-being in oil palm growing villages by island.

(a) Impact of oil palm plantations on village well-being in Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua, evaluated by comparing the change in well-being indicators in villages 5-11 years after industrial oil palm plantation development against the change in well-being in villages without industrial oil palm plantation, while ensuring similar baseline characteristics in both types of villages. (b) Impact of RSPO certification on village well-being in Sumatra and Kalimantan, evaluated by comparing the change in well-being indicators in villages 5-11 years after certification against the change in well-being in villages with non-certified industrial oil palm plantations, while ensuring similar baseline characteristics in both types of villages. N represents the number of villages assessed in each panel. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Size of individual industrial oil palm plantation and number of villages covered by one plantation, by certification status.

(a) Size of each large-scale plantation by certification status in the islands of Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua. (b) Number of villages covered by each large-scale industrial plantation and the proportion of village land area allocated to each plantation, by certification status. Plantation certification status includes (1) RSPO-certified plantations, that is certified large-scale industrial plantations (CERT) and (2) non-certified plantations within oil palm concession boundaries, that is non-certified large-scale industrial plantations (CONC).

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Tables 1–8, Figs. 1–13 and references.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 3

Data used to generate graphs in Fig. 3.

Source Data Fig. 4

Data used to generate diagrams in Fig. 4.

Source Data Fig. 5

Data used to generate graphs in Fig. 5.

Source Data Fig. 6

Data used to generate graphs in Fig. 6.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 1

Data used to generate graphs in Extended Data Fig. 1.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 6

Data used to generate graphs in Extended Data Fig. 6.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 7

Data used to generate graphs in Extended Data Fig. 7.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8

Data used to generate graphs in Extended Data Fig. 8.

Source Data Extended Data Fig. 9

Data used to generate graphs in Extended Data Fig. 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santika, T., Wilson, K.A., Law, E.A. et al. Impact of palm oil sustainability certification on village well-being and poverty in Indonesia. Nat Sustain 4, 109–119 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00630-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-00630-1

This article is cited by

-

Leverage points for tackling unsustainable global value chains: market-based measures versus transformative alternatives

Sustainability Science (2024)

-

Aiding food security and sustainability efforts through graph neural network-based consumer food ingredient detection and substitution

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Replanting unproductive palm oil with smallholder plantations can help achieve Sustainable Development Goals in Sumatra, Indonesia

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Is the EU shirking responsibility for its deforestation footprint in tropical countries? Power, material, and epistemic inequalities in the EU’s global environmental governance

Sustainability Science (2023)

-

What evidence exists on the impact of sustainability initiatives on smallholder engagement in sustainable palm oil practices in Southeast Asia: a systematic map protocol

Environmental Evidence (2022)