Abstract

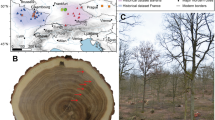

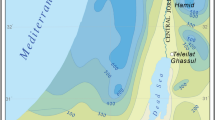

The harvest of plant parts and exudates from wild populations contributes to the income, food security and livelihoods of many millions of people worldwide. Frankincense, an aromatic resin sourced from natural populations of Boswellia trees and shrubs, has been cherished by world societies for centuries. Boswellia populations are threatened by over-exploitation and ecosystem degradation, jeopardizing future resin production. Here, we reveal evidence of population collapse of B. papyrifera—now the main source of frankincense—throughout its geographic range. Using inventories of 23 populations consisting of 21,786 trees, growth-ring data from 202 trees and demographic models on the basis of 7,246 trees, we find that over 75% of studied populations lack small trees, natural regeneration has been absent for decades, and projected frankincense production will be halved in 20 yr. These changes are caused by increased human population pressure on Boswellia woodlands through cattle grazing, frequent burns and reckless tapping. A literature review showed that other Boswellia species experience similar threats. Populations can be restored by establishing cattle exclosures and fire-breaks, and by planting trees and tapping trees more carefully. Concerted conservation and restoration efforts are urgently needed to secure the long-term availability of this iconic product.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data reported in this paper are tabulated in the Supplementary Data and can be accessed in the Github repository (https://github.com/groenendijk/Frankincense-demography).

Code availability

The R script used for the IPM analysis can be accessed in the Github repository (https://github.com/groenendijk/Frankincense-demography).

References

Hamilton, A. C. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodivers. Conserv. 13, 1477–1517 (2004).

Ticktin, T. The ecological implications of harvesting non-timber forest products. J. Appl. Ecol. 41, 11–21 (2004).

Godfray, H. C. J. et al. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science 327, 812 (2010).

Millenium Ecosystem Assessment Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis (Island Press, 2005).

Peres, C. A. et al. Demographic threats to the sustainability of Brazil nut exploitation. Science 302, 2112–2114 (2003).

Groom, N. Frankincense and Myrrh. A Study of the Arabian Incense Trade (Longman, 1981).

Alaamri, M. M. H. Distribution Boswellia sacra in Dhofar mountains, Sultanate of Oman: economic values and environmental role. J. Life Sci. 6, 632–636 (2012).

DeCarlo, A. & Ali, S. H. Sustainable Sourcing of Phytochemicals as a Development Tool: The Case of Somaliland’s Frankincense Industry (Institute for Environmental Diplomacy & Security, 2014).

Kushwaha, C. P. & Singh, K. P. Diversity of leaf phenology in a tropical deciduous forest in India. J. Trop. Ecol. 21, 47–56 (2005).

Singh, K. P. & Kushwaha, C. P. Diversity of flowering and fruiting phenology of trees in a tropical deciduous forest in India. Ann. Bot. 97, 265–276 (2006).

Sagar, R. & Singh, J. S. Tree density, basal area and species diversity in a disturbed dry tropical forest of northern India: implications for conservation. Environ. Conserv. 33, 256 (2006).

Brendler, T., Brinckmann, J. A. & Schippmann, U. Sustainable supply, a foundation for natural product development: the case of Indian frankincense (Boswellia serrata Roxb. ex Colebr.). J. Ethnopharmacol. 225, 279–286 (2018).

Groenendijk, P., Eshete, A., Sterck, F. J., Zuidema, P. A. & Bongers, F. Limitations to sustainable frankincense production: blocked regeneration, high adult mortality and declining populations. J. Appl. Ecol. 49, 164–173 (2012).

Zewdie, W. & Csaplovies, E. Remote sensing based multi-temporal land cover classification and change detection in northwestern Ethiopia. Eur. J. Remote Sens. 48, 121–139 (2015).

Lemenih, M., Arts, B., Wiersum, K. F. & Bongers, F. Modelling the future of Boswellia papyrifera population and its frankincense production. J. Arid Environ. 105, 33–40 (2014).

Gezahgne, A., Yirgu, A. & Kassa, H. Morphological characterization of fungal disease on tapped Boswellia papyrifera trees in Metema and Humera Districts, Northern Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Agric. Sci. 27, 89–98 (2017).

Negussie, A. et al. An exploratory survey of long horn beetle damage on the dryland flagship tree species Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst. J. Arid Environ. 152, 6–11 (2018).

Ogbazghi, W. The Distribution and Regeneration of Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst. in Eritrea. PhD thesis, Wageningen Univ. (2001).

Ogbazghi, W., Rijkers, T., Wessel, M. & Bongers, F. Distribution of the frankincense tree Boswellia papyrifera in Eritrea: the role of environment and land use. J. Biogeogr. 33, 524–535 (2006).

Khamis, M. A., Siddig, E. N. E., Khalil, A. & Csaplovics, E. Changes in forest cover composition of Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst. stands and their consequences, South Kordofan, Sudan. Mediterr. J. Biosci. 1, 99–108 (2016).

Tolera, M., Sass-Klaassen, U., Eshete, A., Bongers, F. & Sterck, F. J. Frankincense tree recruitment failed over the past half century. For. Ecol. Manag. 304, 65–72 (2013).

Zuidema, P. A., Jongejans, E., Chien, P. D., During, H. J. & Schieving, F. Integral Projection Models for trees: a new parameterization method and a validation of model output. J. Ecol. 98, 345–355 (2010).

Rijkers, T., Ogbazghi, W., Wessel, M. & Bongers, F. The effect of tapping for frankincense on sexual reproduction in Boswellia papyrifera. J. Appl. Ecol. 43, 1188–1195 (2006).

Teshome, M., Eshete, A. & Bongers, F. Uniquely regenerating frankincense tree populations in western Ethiopia. For. Ecol. Manage. 389, 127–135 (2017).

Eshete, A., Sterck, F. J. & Bongers, F. Frankincense production is determined by tree size and tapping frequency and intensity. For. Ecol. Manage. 274, 136–142 (2012).

Tilahun, M. et al. Frankincense yield assessment and modeling in closed and grazed Boswellia papyrifera woodlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. J. Arid Environ. 75, 695–702 (2011).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science 342, 850–853 (2013).

Melo, J. B. et al. Striking divergences in Earth Observation products may limit their use for REDD+. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 104020 (2018).

Criteria for Amendment of Appendices I and II. Resolution Conf. 9.24 (Rev. CoP17) (CITES, 2016); https://cites.org/sites/default/files/document/E-Res-09-24-R17.pdf

Holmgren, M. & Scheffer, M. El Niño as a window of opportunity for the restoration of degraded arid ecosystems. Ecosystems 4, 151–159 (2001).

Tierney, J. E., Ummenhofer, C. C. & deMenocal, P. B. Past and future rainfall in the Horn of Africa. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500682 (2015).

Seleshi, Y. & Zanke, U. Recent changes in rainfall and rainy days in Ethiopia. Int. J. Climatol. 24, 973–983 (2004).

Segele, Z. T., Richman, M. B., Leslie, L. M. & Lamb, P. J. Seasonal-to-interannual variability of Ethiopia/Horn of Africa monsoon. Part II: Statistical multimodel ensemble rainfall predictions. J. Clim. 28, 3511–3536 (2015).

van Breugel, P., Friis, I., Demissew, S., Barnekow Lillesø, J. P. & Kindt, R. Current and future fire regimes and their influence on natural vegetation in Ethiopia. Ecosystems 19, 369–386 (2016).

Mengistu, T., Sterck, F. J., Fetene, M. & Bongers, F. Frankincense tapping reduces the carbohydrate storage of Boswellia trees. Tree Physiol. 33, 601–608 (2013).

Abiyu, A. et al. in Degraded Forests in Eastern Africa: Management and Restoration (eds Bongers, F. & Tennigkeit, T.) 133–152 (Earthscan, 2010).

Birhane, E., Kuyper, T. W., Sterck, F. J., Gebrehiwot, K. & Bongers, F. Arbuscular mycorrhiza and water and nutrient supply differently impact seedling performance of dry woodland species with different acquisition strategies. Plant Ecol. Divers. 8, 387–399 (2015).

Lemenih, M. & Kassa, H. Management Guide for Sustainable Production of Frankincense (CIFOR, 2011).

Mekuria, W., Veldkamp, E., Tilahun, M. & Olschewski, R. Economic valuation of land restoration: the case of exclosures established on communal grazing lands in Tigray, Ethiopia. Land Degrad. Dev. 22, 334–344 (2011).

Lemenih, M. & Kassa, H. Re-greening Ethiopia: history, challenges and lessons. Forests 5, 1896–1909 (2014).

Mekuria, W. & Veldkamp, E. Restoration of native vegetation following exclosure establishment on communal grazing lands in Tigray, Ethiopia. Appl. Veg. Sci. 15, 71–83 (2012).

Haile, G., Gebrehiwot, K., Lemenih, M. & Bongers, F. Time of collection and cutting sizes affect vegetative propagation of Boswellia papyrifera (Del.) Hochst through leafless branch cuttings. J. Arid Environ. 75, 873–877 (2011).

Negussie, A., Aerts, R., Gebrehiwot, K., Prinsen, E. & Muys, B. Euphorbia abyssinica latex promotes rooting of Boswellia cuttings. New For. (Dordr.) 37, 35–42 (2008).

Kassa, H., Tefera, B. & Fitwi, G. Preliminary Value Chain Analysis of Gum and Resin Marketing in Ethiopia. Issues for Policy and Research (CIFOR, 2011).

Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248 (1968).

Dietz, T., Ostrom, E. & Stern, P. The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302, 1907–1912 (2003).

Tilahun, M., Maertens, M., Deckers, J., Muys, B. & Mathijs, E. Impact of membership in frankincense cooperative firms on rural income and poverty in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia. For. Policy Econ. 62, 95–108 (2016).

Agrawal, A., Chhatre, A. & Hardin, R. Changing governance of the world’s forests. Science 320, 1460–1462 (2008).

Al-Aamri, M. M. Sustainable Harvesting of Frankincense Trees in Oman (Environment Society of Oman, 2014).

Al-Harrasi, A. et al. Chemical, molecular and structural studies of Boswellia species: beta-Boswellic aldehyde and 3-epi-11beta-dihydroxy BA as precursors in biosynthesis of boswellic acids. PLoS ONE 13, e0198666 (2018).

Khan, A. L. et al. The first chloroplast genome sequence of Boswellia sacra, a resin-producing plant in oman. PLoS ONE 12, e0169794 (2017).

Khan, A. L. et al. Regulation of endogenous phytohormones and essential metabolites in frankincense-producing Boswellia sacra under wounding stress. Acta Physiol. Plant. 40, 113 (2018).

Khan, A. L., Asaf, S., Al-Rawahi, A., Lee, I. J. & Al-Harrasi, A. Rhizospheric microbial communities associated with wild and cultivated frankincense producing Boswellia sacra tree. PLoS ONE 12, e0186939 (2017).

DeCarlo, A., Elmi, A. D. & Johnson, S. Sustainable Frankincense Production Systems in Somaliland. A Management Guide (Conserve the Cal Madow, 2017).

Standard for Good Field Collection Practices of Medicinal Plants (NMPB, Department of AYUSH, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2009).

Mishra, S., Behera, N. & Paramanik, T. Comparative assessment of gum yielding capacities of Boswellia serrata Roxb. and Sterculia urens Roxb. in relation to their girth sizes. Ecoscan 1, 327–330 (2012).

Schweingruber, F. H, Börner, A. & Schulze, E. D. Atlas of Woody Plant Stems: Evolution, Structure and Environmental Modifications (Springer-Verlag, 2006).

Rinn, F. TSAP-Win Software for Tree-ring Measurement Analysis and Presentation (Rinntech, 2003).

Schweingruber, F. H. Tree Rings: Basics and Applications of Dendrochronology (Kluwer Academic, 1988).

Eshete, A., Sterck, F. J. & Bongers, F. Diversity and production of Ethiopian dry woodlands explained by climate- and soil-stress gradients. For. Ecol. Manage. 261, 1499–1509 (2011).

Baker, T. R., Affum-Baffoe, K., Burslem, D. F. R. P. & Swaine, M. D. Phenological differences in tree water use and the timing of tropical forest inventories: conclusions from patterns of dry season diameter change. For. Ecol. Manage. 171, 261–274 (2002).

Chitra-Tarak, R. et al. And yet it shrinks: a novel method for correcting bias in forest tree growth estimates caused by water-induced fluctuations. For. Ecol. Manage. 336, 129–136 (2015).

Zweifel, R., Haeni, M., Buchmann, N. & Eugster, W. Are trees able to grow in periods of stem shrinkage? New Phytol. 211, 839–849 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2018); http://www.R-project.org/

Bates, D., Maechler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Ellner, S. P. & Rees, M. Integral projection models for species with complex demography. Am. Nat. 167, 410–428 (2006).

Kroon, Hd, Groenendael, Jv & Ehrlen, J. Elasticities: a review of methods and model limitations. Ecology 81, 607–618 (2000).

Metcalf, C. J. E., McMahon, S. M., Salguero-Gómez, R. & Jongejans, E. IPMpack: an R package for integral projection models. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 195–200 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the FRAME integrated programme (‘Frankincense, myrrh and arabic gum: sustainable use of dry woodland resources in Ethiopia’). A large part of this programme was financially supported by Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research-Science for Global Development (NWO-WOTRO, grant no. W01.65.220.00). Additional support was received from: a SIDA grant to M.Tol., BES grants 2732/3420 to M.Tol. and 1415/1782 to E.B., Wageningen University Sandwich grants to E.B., M.Tol. and W.O., IFS grant C/4775-1 to M.Tol., NUFFIC grant CF6676/2010 to E.B. and Marie Curie Actions Programme grant PITN-2013-GA607545 to P.G. P.G. was also supported by FAPESP grant 18/01847-0.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B., F.J.S., P.A.Z. and P.G. conceived the study. F.B. and P.G. compiled the data. P.G. and P.A.Z. performed the demographic modelling. M.D. evaluated forest change. F.B., P.A.Z., F.J.S. and P.G. wrote the paper. All authors contributed data and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–8, Supplementary Tables 1–5, Supplementary method 1, Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary References 1–12

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bongers, F., Groenendijk, P., Bekele, T. et al. Frankincense in peril. Nat Sustain 2, 602–610 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0322-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-019-0322-2

This article is cited by

-

Ecological study and forest degradation of the Waldiba Monastery woodland in Tigrai, Ethiopia

Discover Sustainability (2024)

-

Current knowledge and conservation perspectives of Boswellia dalzielii Hutch., an African frankincense tree

Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution (2022)

-

Combined effects of tree size and tapping techniques on resin production of Boswellia dalzielii Hutch., an African frankincense tree

Trees (2022)

-

Development of a population of Boswellia elongata Balf. F. in Homhil nature sanctuary, Socotra island (Yemen)

Rendiconti Lincei. Scienze Fisiche e Naturali (2020)

-

Frankincense facing extinction

Nature Sustainability (2019)