Abstract

Transverse electric graphene plasmons are generally weakly confined in the direction perpendicular to the graphene plane. They are featured by a skin depth δ, namely the penetration depth of their evanescent fields into the surrounding environment, much larger than the wavelength λ in free space (e.g., δ > 10λ). The weak spatial confinement of transverse electric graphene plasmons is now the key drawback that limits their practical applications. Here we report the skin depth of TE graphene plasmons can be largely decreased down to the subwavelength scale (e.g., δ < λ/10) in negative refractive-index environments. The underlying mechanism originates from the different existence conditions for TE graphene plasmons in negative and positive refractive-index environments. To be specific, their existence in negative (positive) refractive-index environments requires Im(σs) > 0 (Im(σs) < 0) and lies in the frequency range of ħω/μc < 1.667 (ħω/μc > 1.667), where σs and μc are the surface conductivity and chemical potential of monolayer graphene, respectively.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In their seminal work in 2007, Mikhailov S. A. and Ziegler K.1 proposed an exotic electromagnetic mode in the monolayer graphene, namely the transverse electric (TE, or s-polarized) graphene plasmons. The TE graphene plasmons lie in the frequency range of ħω/μc > 1.667, since their existence requires Im(σs) < 01, where σs and μc are the surface conductivity and chemical potential of graphene, respectively. Another key feature for TE graphene plasmons is the spatial confinement. Note that highly confined surface plasmons2,3, such as the transverse magnetic (TM, or p-polarized) graphene plasmons4,5,6,7, can enable the flexible control of light flow in the subwavelength scale and even the extreme nanoscale; as such, they can enable many promising applications, including the on-chip terahertz to X-ray radiation sources8,9, miniaturized modulators10, subwavelength guidance11,12,13, deep-subwavelength imaging14,15,16,17, and light energy harvesting and scattering18,19,20. The spatial confinement of graphene plasmons in the direction perpendicular to the graphene plane can be quantitatively characterized by the skin depth δ. Here the skin depth21 is defined as the penetration depth of the evanescent fields carried by graphene plasmons into the surrounding environment. For TE graphene plasmons, their skin depth is inversely proportional to |Im(σs)|1. Due to the small achievable negative-value of Im(σs) (i.e., max(|Im(σs)|) ~ G0 (Fig. 1)), TE graphene plasmons are featured by a skin depth at least in the wavelength scale, where G0 = e2/4ħ is the universal optical conductivity. To be specific, we generally have δ > 10λ (Supplementary Fig. 1) for TE plasmons in monolayer graphene, where λ is the wavelength in free space. As severely limited by the weak spatial confinement, only several potential applications of TE graphene plasmons have been reported, such as Brewster effects22, polarizers23, optical sensors24, waveguide phase, and amplitude modulators25. On the other hand, rapid progress in nano-photonics has fuelled a quest for highly confined TE graphene plasmons, in addition to the highly confined TM graphene plasmons. This way, highly confined graphene plasmons can be achieved without stringent requirement on the polarization of light and can benefit more practical applications based on TE waves. Such a quest still remains elusive, although many researches of TE polaritons in graphene26,27,28,29 and other 2D materials30,31,32,33,34 have been ignited by the pioneering work in 2007.

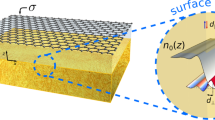

a Structural schematic. The monolayer graphene is located in a symmetric environment with the relative permittivity εr1 = εr2 = εr and the relative permeability μr1 = μr2 = μr. b Existence condition of TE graphene plasmons in environments with various values of εr and μr. c Surface conductivity of monolayer graphene as a function of frequency at 300 K. The emergence of TE graphene plasmons in environments with μr > 0 requires Im(σs) < 0, which exists in the frequency range of ħω/μc > 1.667. In contrast, their emergence in environments with μr < 0 requires Im(σs) > 0, existing in the range of ħω/μc < 1.667. Here we set the chemical potential μc = 0.2 eV and the relaxation time τ = 0.2 ps. G0 = e2/4ħ is the universal optical conductivity.

Here we theoretically reveal a viable way to largely enhance the spatial confinement of TE graphene plasmons by using the environment with the negative permeability or refractive index. As firstly proposed by Veselago in 196835, the negative refractive-index materials simultaneously have negative permittivity and negative permeability; they have triggered tremendous researches both on fundamental science and practical applications36,37,38,39,40, exemplified by the well-known negative refraction41, the perfect lens/superlens37,42, the inverse Doppler effect43,44,45,46 and the backward Cherenkov radiation47,48,49,50. In principle, the environment with the negative permeability or refractive index can be effectively constructed, for example, by metamaterials36,41,51 and photonic crystals52,53,54,55. We find the existence condition of TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments is drastically different from that in positive refractive-index environments. In negative refractive-index environments, the existence of TE graphene plasmons become to require Im(σs) > 0; as a result, TE graphene plasmons now lie in the frequency range of ħω/μc < 1.667 at room temperature. Moreover, due to the availability of the large positive value of Im(σs) (max(|Im(σs)|) ~ 102G0), the skin depth of TE graphene plasmons can be largely decreased down to the subwavelength scale (e.g., δ < λ/10).

Results and discussion

General existence condition for TE graphene plasmons

We focus on the discussion of TE surface plasmons supported by the monolayer graphene. For TE graphene plasmons, their in-plane wavevector q (parallel to the graphene plane) is generally comparable to the wavevector k0 = ω/c of light in free space, where c is the speed of light in free space. As such, the nonlocal response of graphene is negligible, and it is reasonable to use the local Kubo formula to describe the surface conductivity σs of graphene. That is σs = σs,intra + σs,inter, where

and \(\sigma _{{\mathrm{s}},{\mathrm{inter}}} = \frac{{ie^2(\omega + \frac{i}{\tau })}}{{\pi \hbar ^2}}{\int}_0^\infty {\frac{{f_d\left( { - x} \right) - f_d(x)}}{{(\omega + \frac{i}{\tau })^2 - 4(\frac{x}{\hbar })^2}}} dx\). Here σs,intra and σs,inter are the parts of the conductivity related to the intra-band and inter-band transitions, respectively; \(f_d\left( x \right) = (e^{\frac{{x - \mu _{\mathrm{c}}}}{{k_BT}}} + 1)^{ - 1}\) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function; e is the electron charge, T is the temperature, τ is the relaxation time, and μc is the chemical potential.

Figure 1 shows the general existence condition for TE graphene plasmons. The monolayer graphene is located at the interface between region 1 and region 2 (Fig. 1a). Region 1 with z < 0 (region 2 with z > 0) has the relative permittivity εr1 (εr2) and the relative permeability μr1 (μr2). For conceptual demonstration, we let εr1 = εr2 = εr and μr1 = μr2 = μr. From the classical electromagnetic wave theory (see Supplementary Notes1 and 2), the dispersion for TE graphene plasmons is governed by

where \(k_{\mathrm{z}} = \sqrt {\frac{{\omega ^2}}{{c^2}}\varepsilon _{\mathrm{r}}\mu _{\mathrm{r}} - q^2}\) is the out-of-plane (perpendicular to the graphene plane) component of wavevector; μ0 is the permeability in free space.

Equation (2) explicitly indicates the existence condition for TE graphene plasmons, as briefly summarized in Fig. 1b, c. To be specific, for the environment with μr > 0 (e.g., positive refractive-index environments), Eq. (2) has solutions only if Im(σs) < 0, where the negative Im(σs) lies in the frequency range of ħω/μc > 1.667 (Fig. 1c). In contrast, for the environment with μr < 0 (e.g., negative refractive-index environments), the existence of TE graphene plasmons becomes to require Im(σs) > 0 from Eq. (2) (Fig. 1b) and lies in the range of ħω/μc < 1.667 at room temperature (Fig. 1c).

On the other hand, Eq. (2) also indicates that the skin depth of TE graphene plasmons is proportional to 1/|Im(σs)| for arbitrary μr, since the skin depth is mathematically defined as δ = 1/Im(kz). In other words, in the frequency range where TE graphene plasmons could exist, a larger value of |Im(σs)| would lead to a smaller skin depth and thus a larger spatial confinement. Note that the value of Im(σs) for the monolayer graphene is dominantly determined by σs,intra especially in the frequency range of ħω/μc ≪ 1.667, while it is mainly determined by σs,inter if ħω/μc > 1.667. As a result, the maximum value of |Im(σs)| can reach ~40G0 at ħω/μc < 1.667 due to the contribution of σs,intra (Fig. 1c); in contrast, it is only ~0.3G0 at ħω/μc > 1.667 with the negligible contribution from σs,intra (Fig. 1c). This way, the minimum skin depth of TE graphene plasmons in negative permeability environments would be much smaller than that in positive permeability environments.

Moreover, if ħω/μc ≪ 1.667, σs,intra in Eq. (1) is dependent on the temperature T, the relaxation time τ, and the chemical potential μc, besides the angular frequency ω. These parameters (T, τ and μc) provide us extra degrees of freedom to achieve the large value of |Im(σs)|; see for example in Fig. 2. Then in negative permeability environments, these parameters could enable us the capability to flexibly modulate the basic features of TE graphene plasmons (Figs. 2 and 3), including their spatial confinement. Below the influence of these parameters on TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments is analyzed in detail, where the negative refractive-index environment (μr < 0 and εr < 0) is a typical negative permeability environment (μr < 0). In addition, the loss in the surrounding environment is artificially neglected, since the reasonable amount of loss will not have a drastic influence on the confined TE graphene plasmons.

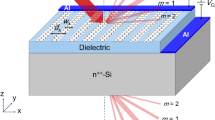

For conceptual demonstration, the negative refractive-index environment has the relative permittivity εr = −1 and the relative permeability μr = −1. a Surface conductivity of monolayer graphene for different values of relaxation time τ. b Dispersion of TE graphene plasmons. For each dispersion curve, its peak (highlighted by the solid dot) corresponds to the maximum in-plane wavevector Re(q)peak of TE graphene plasmons at the frequency of ωpeak. c Influence of the relaxation time on Re(q)peak and ωpeak. Here μc = 0.2 eV and T = 300 K. In c the colored dots are extracted from (b); the black solid line (i.e., relation between ωpeak and τ) is the analytical solution of \(d\left[ {\frac{{{\mathrm{Re}}\left( q \right)}}{{k_0}}} \right]{\mathrm{/}}d\omega = 0\); the gray solid line (relation between Re(q)peak and τ) is obtained by substituting the analytical solution of ωpeak into Eq. (3).

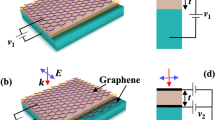

a In-plane wavevector Re(q) of TE graphene plasmons (normalized by the wavevector of light in free space k0) as a function of the temperature T. b, c Skin depth δand quality factor Re(q)/Im(q) of TE graphene plasmons at different temperatures and chemical potentials (their values are denoted in the figure). λ is the wavelength of light in free space. Here εr = −1, μr = −1, and the electron mobility is μ = 10000 cm2 V−1 s−1. The corresponding relaxation time can be obtained from \(\tau = \mu _{\mathrm{c}}\mu {\mathrm{/}}(ev_F^2)\), where vF = 1 × 106 m s−1 is the Fermi velocity.

Influence of the relaxation time on TE graphene plasmons

Figure 2 shows the influence of relaxation time on TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments, from the perspective of the in-plane wavevector. According to Eq. (2), it is straightforward to derive the expression for the in-plane wavevector q, that is

To facilitate the discussion, the effective refractive index of TE graphene plasmons is denoted as neff,0 = Re(q)/k0 and plotted in Fig. 2; see the information of Im(q)/k0 in Supplementary Fig. 2 in Supplementary Note 3. In addition, since the quality factor Re(q)/Im(q) is oftentimes regarded as a key parameter to characterize the basic feature of surface plasmons, the quality factor of TE graphene plasmons is also briefly discussed in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4 in Supplementary Note 4. For the monolayer graphene, the maximum positive value of Im(σs) appears in the frequency range of ħω/μc < 0.1 (Fig. 2a). If the relaxation time increases (i.e., the loss in graphene decreases), max(|Im(σs)|) in the interested frequency range increases and can be up to ~100G0 (Fig. 2a). Due to the availability of large positive Im(σs), the maximum neff,0 in negative refractive-index environment is much larger than 1 (e.g., up to neff,0 ≈ 1.4 in Fig. 2b, c; also see Supplementary Note 5), and the maximum value of neff,0 would increase if the relaxation time increases. Such a large value of neff,0 is favored for the practical application of TE graphene plasmons. We emphasize that in positive refractive-index environment, neff,0 is generally very close to 1, such as neff,0 ≈ 1.00006 in Supplementary Fig. 5 in Supplementary Note 6.

Influence of Tand μ c on TE graphene plasmons

Figure 3 shows the influence of the temperature T and the chemical potential μc on TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments. In short, if the temperature or the chemical potential increases, the achievable maximum value of neff,0 for TE graphene plasmons would increase, e.g., up to neff,0 = 1.65 in Fig. 3a. We note that in Fig. 3a, the achievable maximum value of neff,0 at high temperatures is more sensitive to the temperature variation than that at low temperatures. This phenomenon is caused by the fact that in Eq. (1), the temperature-insensitive term of \(\frac{{ie^2k_{\mathrm{B}}T}}{{\pi \hbar ^2\left( {\omega + \frac{i}{\tau }} \right)}} \cdot \frac{{\mu _{\mathrm{c}}}}{{k_{\mathrm{B}}T}} = \frac{{ie^2\mu _c}}{{\pi \hbar ^2\left( {\omega + \frac{i}{\tau }} \right)}}\) plays a dominant role at low temperatures for σs,intra, while the temperature-sensitive term of \(\frac{{ie^2k_{\mathrm{B}}T}}{{\pi \hbar ^2\left( {\omega + \frac{i}{\tau }} \right)}} \cdot 2\ln ( {e^{ - \frac{{\mu _{\mathrm{c}}}}{{k_BT}}} + 1} )\) becomes important to σs,intra at high temperatures.

Correspondingly, if the temperature or the chemical potential increases, the minimum skin depth of TE graphene plasmons would decrease (Fig. 3b). To be specific, the minimum skin depth of TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments can readily become subwavelength, such as δ/λ < 1 for the case with μc = 0.2 eV at T = 300 K in Fig. 3b. Furthermore, the skin depth can even be decreased down to the deep-subwavelength scale, such as δ/λ < 0.1 for the case with μc = 0.5 eV at T = 300 K in Fig. 3b. As such, the usage of negative refractive-index environments can largely decrease the minimum skin depth of TE graphene plasmons by at least two orders of magnitude, compared to positive refractive-index environments in which δ/λ > 10 (Supplementary Fig. 1). We emphasize that the enticing subwavelength skin depth of TE graphene plasmons can already be achieved at room temperature, although the temperature’s influence in Fig. 3 is studied in a relatively wide range of temperature and the high temperature such as 3000 K in practical scenarios might lead to the instability of negative refractive-index materials. Moreover, it is worthy to highlight that the phenomenon of the temperature-induced large enhancement of the spatial confinement for TE graphene plasmons is only exists in negative refractive-index environments (Fig. 3) and will not happen for positive refractive-index environments (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments generally have a relatively small quality factor Re(q)/Im(q) (Fig. 3c), due to their high spatial confinement and the large material loss of graphene at the studied frequency range.

Influence of μ r and ε r on TE graphene plasmons

Figure 4 shows the drastic difference of TE graphene plasmons in positive and negative refractive-index environments from another perspective of view, that is, the influence of |μr| and |εr| on Re(q)/|k|, where \(k = k_0\sqrt {\varepsilon _{\mathrm{r}}\mu _{\mathrm{r}}}\) is the wavevector of light in the surrounding environment. Physically, Re(q)/|k| is equivalent to the ratio between the wavelength of light in the surrounding environment λenviron and the wavelength of TE graphene plasmons λplasmon, namely Re(q)/|k| = λenviron/λplasmon. That is, a large Re(q)/|k| indicates a larger contrast between λenviron and λplasmon. Note that k ≠ k0 where k0 is the wavevector of light in free space, and thus Re(q)/|k| is not the effective refractive index of TE graphene plasmons neff,0 = Re(q)/k0 discussed in Figs. 2 and 3.

Here the in-plane wavevector Re(q) of TE graphene plasmons is normalized by the wavevector \(k = k_0\sqrt {\varepsilon _r\mu _r}\) of light in the surrounding environment. The setup of monolayer graphene is the same as that in Fig. 2a with the relaxation time τ = 0.2 ps. For comparison, the influence of |μr| and |εr| on TE graphene plasmons in positive refractive-index environments is also shown. For the negative refractive-index environments, εr < 0 and εr < 0 and T = 300 K; for the positive refractive-index systems, μr > 0, εr > 0 and T = 100 K. The environments with εr near zero or μr near zero can be effectively constructed for example via metamaterials36,41,51, photonic crystals52,53,54,55, and waveguides57,58,59.

From Fig. 4, the variation of both |μr| and |εr| for negative refractive-index environments would have a large impact on Re(q)/|k| than that for positive refractive-index environments. To be specific, in negative refractive-index environments, Re(q)/|k| > 10 is achievable if we increase |μr| and decrease |εr|. As such, a larger contrast between λenviron and λplasmon exists in negative refractive-index environments. In contrast, in positive refractive-index environments, Re(q)/|k| is insensitive to the variation of |μr| and |εr|, and it is always very close to 1. Therefore, there is the negligible contrast between λenviron and λplasmon in positive refractive-index environments. Note that the large value of Re(q)/|k| is favored in practical applications, which can be used, for example, to achieve the extraordinarily large scattering cross section from tiny objects in low-index environments56. More discussion on the influence of |μr| and |εr| can be obtained in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7 in Supplementary Note 7.

In conclusion, we have theoretically revealed some emerging features of TE graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index environments, including their existence condition of Im(σs) > 0 and their existing frequency range of ħω/μc < 1.667. Importantly, these TE graphene plasmons can become highly confined in the direction perpendicular to the graphene plane. To be specific, their skin depth can decrease down to the deep-subwavelength scale (e.g., δ < λ/10). Then the existence of these highly confined TE graphene plasmons should be robust to various surrounding environments (i.e., the permittivity and/or permeability of the substrate and superstrate can be largely different). Such a feature is drastically different from the weakly confined TE graphene plasmons in the positive refractive-index environment, which exist mainly in the almost symmetric environments (the substrate and superstrate should have the negligible difference in their permittivity or permeability)1,28. Our findings in this work further indicate that the negative refractive-index materials might serve as a versatile platform to enable more practical applications of TE graphene plasmons, such as subwavelength guidance, some exotic scattering phenomena of light, and the exploration of TE plasmons in controlling the free electron radiation (e.g., Cherenkov radiation).

Methods

Dispersion of TE graphene plasmons

Without loss of generality, the monolayer graphene is located at the interface between region 1 and region 2 (Fig. 1a), where region 1 with z < 0 (region 2 with z > 0) has the relative permittivity εr1 (εr2) and the relative permeability μr1 (μr2). For TE graphene plasmons, their electric fields are along the y direction. According to the electromagnetic theory19, one can set the electric fields in each region as

Accordingly, the relationship between kz1,2 and q is

In the above equations, q is the component of the wavevector parallel to the interface, kz1 and kz2 are the component of the wavevector perpendicular to the interface in region 1 and region 2, respectively, and ω is the angular frequency. The magnetic field in each region can be obtained according to ∇ × E = iωμH. By enforcing the boundary conditions:

we can obtain the dispersion of TE graphene plasmons as

where μ0 is the permeability in free space.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Mikhailov, S. A. & Ziegler, K. New electromagnetic mode in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 016803 (2007).

Basov, D. N., Fogler, M. M. & García de Abajo, F. J. Polaritons in van der Waals materials. Science 354, 195–204 (2016).

Low, T. et al. Polaritons in layered two-dimensional materials. Nat. Mater. 16, 182–194 (2017).

Grigorenko, A. N., Polini, M. & Novoslov, K. S. Graphene plasmonics. Nat. Photon 6, 749–758 (2012).

Koppens, F. H. L., Chang, D. E. & García de Abajo, F. J. Graphene plasmonics: A platform for strong light–matter interactions. Nano Lett. 11, 3370–3377 (2011).

Xu, Q. et al. Effects of edge on graphene plasmons as revealed by infrared nanoimaging. Light Sci. Appl 6, e16204 (2017).

Lu, Y. et al. Highly efficient plasmon excitation in graphene-Bi2Te3 heterostructure. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 33, 1842–1846 (2016).

Wong, J. L., Kaminer, I., Ilic, O., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Towards graphene plasmon-based free-electron infrared to X-ray sources. Nat. Photonics 10, 46–52 (2016).

Rosolen, G. et al. Metasurface-based multi-harmonic free-electron light source. Light Sci. Appl 7, 64 (2018).

Liu, M. et al. A graphene-based broadband optical modulator. Nature 474, 64–67 (2011).

Liu, L., Han, Z. & He, S. Novel surface plasmon waveguide for high integration. Opt. Express 13, 6645–6650 (2005).

Vakil, A. & Engheta, N. Transformation optics using graphene. Science 332, 1291–1294 (2011).

Iranzo, D. A. et al. Probing the ultimate plasmon confinement limits with a van der Waals heterostructure. Science 360, 291–295 (2018).

Zhu, J. et al. A holey-structured metamaterial for acoustic deep-subwavelength imaging. Nat. Phys. 7, 52–55 (2011).

Sapienza, R. et al. Deep-subwavelength imaging of the modal dispersion of light. Nat. Mater. 11, 781–787 (2012).

Lin, X. et al. All-angle negative refraction of highly squeezed plasmon and phonon polaritons in graphene-boron nitride heterostructures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 6717–6721 (2017).

Jiang, J., Lin, X. & Zhang, B. Broadband negative refraction of highly squeezed hyperbolic polaritons in 2D materials. Research 2018, 2532819 (2018).

Aubry, A. et al. Plasmonic light-harvesting devices over the whole visible spectrum. Nano Lett. 10, 2574–2579 (2010).

Qian, C. et al. Experimental observation of superscattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 063901 (2019).

Qian, C. et al. Multifrequency superscattering from subwavelength hyperbolic structures. ACS Photonics 5, 1506–1511 (2018).

Kong, J. A. Electromagnetic Wave Theory (EMW Publishing, Cambridge, 2008).

Lin, X., Shen, Y., Kaminer, I., Chen, H. S. & Soljačić, M. Transverse-electric Brewster effect enabled by nonmagnetic two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. A 94, 023836 (2016).

Bao, Q. et al. Broadband graphene polarizer. Nat. photonics 5, 411–415 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. Refractive index mapping of single cells with a graphene-based optical sensor. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 242, 41–46 (2017).

Shkerdin, G., Alkorre, H., Guoqiang, H. & Stiens, J. H. Modified TE modes of metal waveguide with integrated graphene structure in the sub-terahertz frequency rang. IET Microw. Antenna P 10, 692–699 (2016).

Ye, Q. et al. Polarization-dependent optical absorption of graphene under total internal reflection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 021912 (2013).

Bludov, Y. V., Smirnova, D. A., Kivshar, Y. S., Peres, N. M. R. & Vasilevskiy, M. I. Nonlinear TE-polarized surface polaritons on graphene. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035406 (2014).

Bordag, M. & Pirozhenko, I. G. Transverse-electric surface plasmon for graphene in the Dirac equation model. Phys. Rev. B 89, 035421 (2014).

Chamanara, N. & Caloz, C. Graphene transverse electric surface plasmon detection using nonreciprocity modal discrimination. Phys. Rev. B 94, 75413 (2016).

Musa, M. Y. et al. Confined transverse electric phonon polaritons in hexagonal boron nitrides. 2D Mater. 5, 015018 (2018).

Lin, X. et al. Tailoring the energy distribution and loss of 2D plasmon. N. J. Phys. 18, 105007 (2016).

Merano, M. Transverse electric surface mode in atomically thin boron-nitride. Opt. Lett. 41, 2668–2671 (2016).

Ukhtary, M. S., Nugraha, A. R. T. E., Hasdeo, H. & Saito, R. Broadband transverse electric surface wave in silicine. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 063103 (2016).

Lin, X. et al. Chiral plasmons with twisted atomic bilayers. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.10474 (2020).

Veselago, V. G. The electrodynamics of substances with simultaneously negative values of permittivity and permeability. Sov. Phys. Usp. 10, 509–514 (1968).

Cui, T. J., Smith, D. R. & Liu, R. P. Metamaterials: Theory, Design, and Applications (Springer, New York, 2010).

Pendry, J. B. Negative refraction makes a perfect lens. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3966–3969 (2000).

Smith, D. R. et al. Composite medium with simultaneously negative permeability and permittivity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 4184–4187 (2000).

Shen, L. et al. Broadband enhancement of on-chip single-photon extraction via tilted hyperbolic metamaterials. Appl. Phys. Rev. 7, 021403 (2020).

Hu, H. et al. Controlling Cherenkov threshold with nonlocality. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2002.04252 (2020).

Shelby, R. A., Smith, D. R. & Schultz, S. Experimental verification of a negative index of refraction. Science 292, 77–79 (2001).

Zhang, X. & Liu, Z. Superlenses to overcome the diffraction limit. Nat. Mater. 7, 435–441 (2008).

Shi, X. et al. Superlight inverse Doppler effect. Nat. Phys. 14, 1001–1005 (2018).

Lin, X. & Zhang, B. Normal Doppler frequency shift in negative refractive-index systems. Laser Photonics Rev. 13, 1900081 (2019).

Bearpark, T. & Seddon, N. Observation of the inverse Doppler effect. Science 302, 1537–1540 (2003).

Chen, J. et al. Observation of the inverse Doppler effect in negative-index materials at optical frequencies. Nat. Photonics 5, 239–242 (2011).

Xi, S. et al. Experimental verification of reversed Cherenkov radiation in left-handed metamaterial. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 194801 (2009).

Chen, H. & Chen, M. Flipping photons backward: reversed Cherenkov radiation. Mater. Today 14, 34–41 (2011).

Lin, X. et al. Controlling Cherenkov angles with resonance transition radiation. Nat. Phys. 14, 816–821 (2018).

Luo, C., Ibanescu, M., Johnson, S. G. & Joannopoulos, J. D. Cerenkov radiation in photonic crystals. Science 229, 368–371 (2003).

Valentine, J. et al. Three-dimensional optical metamaterial with a negative refractive index. Nature 455, 376–379 (2008).

Cubukcu, E., Aydin, K., Ozbay, E., Foteinopoulou, S. & Soukoulis, C. M. Negative refraction by photonic crystals. Nature 423, 604–605 (2003).

Huang, X., Lai, Y., Hang, Z. H., Zheng, H. & Chan, C. T. Dirac cones induced by accidental degeneracy in photonic crystals and zero-refractive-index materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 582–586 (2011).

Joannopoulos, J. D., Johnson, S. G., Winn, J. N. & Meade, R. D. Photonic Crystals: Molding the Flow of Light (Princeton University Press, Princeton, 2008).

Song, J. et al. Efficient excitation of multiple plasmonic modes on three-dimensional graphene: an unexplored dimension. ACS Photonics 3, 1986–1992 (2016).

Zhou, M., Shi, L., Zi, J. & Yu, Z. Extraordinarily large optical cross section for localized single nanoresonator. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 023903 (2015).

Silveirinha, M. & Engheta, N. Tunneling of electromagnetic energy through subwavelength channels and bends using ε-near-zero materials. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 157403 (2006).

Edwards, B., Alu, A., Young, M. E., Silveirinha, M. & Engheta, N. Experimental verification of epsilon-near-zero metamaterial coupling and energy squeezing using a microwave waveguide. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 033903 (2008).

Liberal, I., Mahmoud, A. M., Li, Y., Edwards, B. & Engheta, N. Photonic doping of epsilon-near-zero media. Science 355, 1058–1062 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The work was sponsored by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NNSFC) under Grants No. 61625502, No.11961141010, and No. 61975176, the Top-Notch Young Talents Program of China, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities and the Singapore Ministry of Education (Grant No. MOE2018-T2-1-022 (S) and MOE2016-T3-1-006).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.L. conceived the idea. X.Z. performed the calculations. H. H., X.L., L.S., B.Z., and H.C. contributed insight and discussion on the results. X.Z. and X.L. wrote the paper. X.L., B.Z. and H.C., supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Hu, H., Lin, X. et al. Confined transverse-electric graphene plasmons in negative refractive-index systems. npj 2D Mater Appl 4, 25 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-00159-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-020-00159-z

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic manipulation of microwave polarization based on anisotropic graphene meta-device

npj 2D Materials and Applications (2022)