Abstract

The out-of-phase inter-decadal co-variability between summer (JJA) sea ice extent (SIE) in the Kara Sea (KS) sector of the Arctic Ocean and Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall (ISMR) is found to be weakened during the recent decades with rapidly declining SIE in the KS (since the 1980s). However, SIE in the KS and frequency of ISMR extremes are found to have a consistent out-of-phase relation during the rapidly declining SIE periods. A possible physical mechanism for the relation between the late-season ISMR extremes and summer SIE in the KS is suggested, focusing on the recent years since the 1980s.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall (ISMR) is the major source of drinking water to more than a billion people, owing to its roughly 70% contribution to the annual precipitation. The variability in it has a direct impact on agriculture and thus strongly influences the national economy. The increasing frequency of extreme ISMR events1,2, causing severe flooding and huge socio-economic challenges, demand adequate adaptation and mitigation strategies. Understanding both the local driving factors and remote teleconnections of extreme ISMR events is key for better assessment and improved future projections of extreme ISMR events at different time scales. This is in particular of great importance given that in a warmer climate, the climate models project further increase in the frequency of ISMR extremes3.

Although a considerable amount of studies have been conducted on northern hemisphere mid-latitude teleconnections to ISMR, only a few of those have identified linkages between ISMR and sea ice in the Arctic. Krishnamurty et al. 4 proposed that a large amount of heat, released in the atmosphere during extreme rainfall events over northwest India, ultimately travels to the Canadian Arctic region causing significant sea ice loss. It is further noted that the amount of sea ice concentration (SIC) variability in the Arctic due to the Rossby wave train generated from East Asian Summer monsoon and Indian Summer Monsoon together is comparable with the SIC variability induced by Arctic Oscillation5. On the other hand, while the effects of Arctic sea ice changes on the mid-latitudes are still debated6,7, it is often argued that concurrent increase in mid-latitude extreme weather events is associated with ‘Arctic Amplification’ induced changes in sea ice conditions8. A recent study further suggests that the impact of projected future sea ice changes in the Arctic can also reach the tropics9. Since the beginning of the satellite records in 1979, the Arctic sea ice extent (SIE) has been consistently declining at a very alarming rate with the largest trend of 12.9 ± 2.2% per decade in September and about 4.4% per decade in annual mean6. However, it is still unclear if this rapid sea ice decline can influence the tropical extremes, or in particular the extreme rainfall events during ISMR.

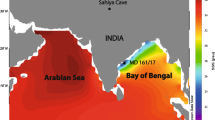

Here, we investigate the Arctic sea ice and ISMR relation for the last ~100 years. The specific focus of the study is on the Kara Sea (KS) SIE, which is argued to have a strong influence on the lower latitudes10. Further, the KS is one of the regions with the largest summer sea ice loss causing strong seasonal variability in sea ice cover and heat fluxes to the atmosphere6,11. A possible physical mechanism for the effect of SIE variability in the KS on ISMR extremes is also proposed.

Results and discussion

Long-term variability of ISMR and sea ice in the KS

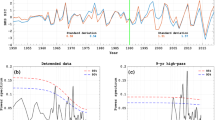

The multi-decadal variability of SIE in the KS during summer (JJA) and ISMR (JJAS) in central India (19o–26oN; 75o–85oE) is shown in Fig. 1a. Rapid decline of SIE is observed since the 1980s, and during the Early Twentieth Century Warming period (ETCW, 1920–1940); the time period which exhibited rapid warming of the surface air temperature (SAT) with reduced SIE in the Arctic Ocean12,13 and followed by an increase in SIE. The mean ISMR showed an opposite phase co-variability with an increasing trend during the ETCW and a subsequent decrease. However, during the recent rapid SIE decline since 1980, mean ISMR does not show a similar opposite phase co-variability. The correlation between the time series of JJA SIE in the KS and mean ISMR rainfall, as shown in Fig. 1a, reduces from −0.6 (p < 0.01) during 1901–1979 to 0.1 (p > 0.1) for the period 1980–2016. It should be noted here that the mid-latitude natural climate variabilities, e.g., Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO), Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO), are argued to contribute to the warming in the Arctic during ETCW14,15. Further, their potential influence on multidecadal variability of ISMR is also known16,17,18. On the contrary, the recent warming trend in the Arctic is mostly driven by anthropogenic forcing13,19. Thus, it can be argued that the observed out-of-phase co-variability in SIE and ISMR during ETCW is mostly driven by the mid-latitude natural climate variabilities (e.g AMO, PDO), whereas the differential response of those to anthropogenic forcing induced warming could possibly have affected the mid-latitude control on their relation. Interestingly, the frequency of ISMR extremes (defined as number of grid points in central India with daily rainfall > 150 mm day−1) is found to have a consistently increasing trend with declining SIE during both ETCW and recent warming since the 1980s. During these periods the correlation between JJA SIE in the KS and frequency of IMSR extremes, as shown in Fig. 1a, shows a very high correlation (r = −0.9, p < 0.01 during 1920–1940 and r = −0.8, p < 0.01 during 1980–2016). To further analyse this relation and the possible physical mechanism for this, we next focus on the recent warming period since 1980, when the reanalysis products are of considerably better quality than earlier periods. This would also allow us to delineate the possible mechanisms associated with rapidly increasing ISMR extremes in absence of any prominent change in the mean ISMR trend.

a SIE (105 sq. km) during JJA in the KS region of the Arctic Ocean (blue line, note that the scale is reversed), number of grid cells in central India (19oN–26oN; 75oE–85oE) with rainfall exceeding 150 mm day−1 during JJAS (red line), averaged rainfall over central India during JJAS (black line). All time series are smoothed with 11-yr running mean. b Anomalies in number of grid points in central India (19oN–26oN; 75oE–85oE) with rainfall exceeding 150 mm day−1 during September. The time series is generated by removing the time mean (for 1980–2017) of number of grid points satisfying the above criteria from the respective individual year values, smoothing with a 5-yr running mean, and finally detrended and normalized. Episodes of increased (red shaded)/reduced (blue shaded) September extreme rainfall years are identified when the time series is positive/negative for at least five consecutive years. c Averaged difference in anomalous JJA sea ice concentration (%) between years with the increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) extreme rainfall years in September. d Same as in (c) but for turbulent heat flux (latent + sensible, W m−2). Significant differences at 90% are dashed in (c) and (d). Barents Sea (BS) and Kara Sea (KS) regions are marked in (c).

Possible mechanism for the KS SIE influence on ISMR extremes

The intra-decadal variability of the frequency of extreme rainfall events during September is shown in Fig. 1b. We found the intra-decadal out-of-phase co-variability between JJA SIE in the KS and frequency of extreme ISMR rainfall is most robust during the later phase of ISMR (Fig. S1), particularly during September. This prompted us to identify the episodes with increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) frequency of September extreme events in Central India as marked in Fig. 1b (see the figure caption for details). We then performed a composite analysis for those years to obtain further insights on the possible physical mechanism responsible for the observed relation between SIE in the KS and frequency of September extreme events over central India (hereafter referred to as ‘extreme events’ only for brevity). Considering the relatively longer memory of sea ice than the atmosphere, it can be expected that the atmospheric response to the changes in JJA sea ice is realized in successive months. Thus we performed the composite analysis based on averaged monthly anomalies during August–September.

To obtain the spatial pattern of sea ice changes associated with the variability in extreme events we plotted the averaged difference in SIC between years with increased and reduced frequency of extreme events (Fig. 1c). The analysis suggests significant negative SIC anomalies, with maximum magnitude in the KS region, associated with increased frequency of extreme events. The changes in surface heat flux due to reduced sea ice can potentially influence the atmospheric conditions20. Consistent with the SIC pattern, the largest contribution in heat flux to the atmosphere (negative values in Fig. 1d) is observed in KS region indicating the potential importance of the KS sea ice to influence the overlying atmospheric conditions.

Next, we investigated the KS sea ice-induced large-scale circulation anomalies associated with the variability in extreme events. Figure 2a shows the averaged difference in upper level (200 hPa) geopotential height (GPH) anomaly during August–September, between the increased and reduced extreme events years. Significant positive GPH anomaly over northwest Europe can be noticed, depicting an anomalously strong Euro-Atlantic blocking-like pattern. Simultaneous strengthening of sub-tropical high over East Asia (Fig. 2a), an important upper atmospheric feature favourable for ISMR21, is also found.

a Averaged difference between years with the increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) extreme rainfall years in September for 200 hPa (a) geopotential height (m, shaded), wind (m s−1, vectors), velocity potential (106 m2 s−1, contours) anomaly during August–September. Only vectors with magnitude >2 m s−1 and negative velocity potential (indicating divergence) contours (black contour indicates the zero velocity potential contour; contour interval: 0.05) are shown for clarity. b, c Same as (a) but for (b) zonal wind anomaly (m s−1) and (c) meridional wind anomaly (m s−1). d Averaged difference in anomalous meridional circulation averaged over 30o–60oE between years with the increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) extreme rainfall in September. All the monthly anomalies are calculated based on 1979–2017 monthly climatology. Significant differences at 90% level from two-tailed t-test are dotted in (a)–(c). The vertical velocity component in (d) is multiplied by 1000 to scale with the v-component.

The warming in the Arctic and resulting sea ice loss has been widely argued to influence the mid-latitude weather patterns through altering the jet stream characteristics due to reduced pole-midlatitude temperature gradient (see Cohen et al. 22 and references therein). However, to what extent Arctic sea ice loss is responsible for altering the jet stream characteristics is still being debated23. A recent modelling study suggests a combined effect of the Arctic sea ice loss and Eurasian snow cover can induce blocking high events over Europe through anomalous Eurasian wave train24. Nonetheless, the significantly weakened zonal flow with increased meridionality (Fig. 2b, c) can induce favourable conditions for anomalous high over northwest Europe during reduced sea ice years in the KS. Further, it has been argued that the dynamical response of the atmosphere to reduced sea ice and surface warming in the Arctic can be important during summer25. An anomalous meridional circulation is established with an ascending branch over the warm Barents/KS region and descending branch over northwest Europe (Fig. 2d). This can further result in anomalous high over northwest Europe and warm the SAT (Fig. S2).

Analysis of the eddy stream function and Rossby wave activity flux during years with increased and reduced extreme events (Fig. 3) suggests propagation of Rossby wave trains from northwest Europe towards East Asia, influencing the sub-tropical high over East Asia. The wave trains show two major pathways; the first one zonally propagates eastward locked around 60oN latitude and the other one moves southward from Europe before diverting towards the east and reaching the East Asian region. Associated eddy stream functions along this pathway are also notable in Fig. 3, consistent with the GPH anomalies as observed in Fig. 2a. Note that a similar path had been earlier attributed to linking the Arctic Oscillation-induced anomalies and the tropical Indian Ocean precipitation during winter26.

Eddy stream functions (shades, 106 m2 s−1) and Rossby wave activity flux (contours, m2 s−2) as in Takaya and Nakamura (2001)27 during August–September averaged for years with (a) increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and (b) reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) extreme rainfall in September over central India. Vectors with magnitude >0.1 m2 s−2 are shown for clarity.

The above findings suggest a plausible physical mechanism through which sea ice anomalies in the KS region can potentially influence the sub-tropical high over East Asia. In short, reduced SIE in the KS can induce anomalous high over northwest Europe, which triggers a Rossby wave train and induces positive upper-level GPH anomalies over the East Asian region. However, the upper-tropospheric anomalies thus established in the East Asian region cannot alone cause the extreme events over central India as they require a sufficient amount of lower atmospheric moisture supply into the region. We found that the anomalous circulation due to strengthened East Asian sub-tropical high induces upper-level divergence over northwest–central India (dashed contour lines in Fig. 2a) during years with increased extreme events. This can further favour the development of cyclonic circulation at the low level. Warm sea surface temperature anomaly in the northwestern Arabian Sea (Fig. S3) along with the upper-level divergence results in the development of anomalous cyclonic circulation at the surface (Fig. 4). Associated with this, enhanced convection can be realized from the anomalous upward vertical velocity over the central Indian region (Fig. 4). Further, it should be noted that the anomalous cyclonic circulation and enhanced convection may not be enough to result in extreme precipitation unless there is an adequate amount of moisture available in this region. In fact, it is known that moisture supplied predominantly from the Arabian Sea plays an important role in causing extreme precipitation events in central India2. The anomalous cyclonic circulation, as observed in Fig. 4, strengthens the westerlies over the Arabian Sea and causes enhanced moisture convergence over central India (Fig. S4). Analogous opposite phase circulation features as described above can be found during years with reduced extreme events. Thus, we propose that the superimposition of the upper (induced by SIE changes in KS) and lower level (induced by warm SST anomalies in northern Arabian Sea) circulation anomalies can potentially favour extreme rainfall events over central India during the late ISMR season (Fig. 5).

Vertical velocity anomaly (shaded, Pa s−1) and 850 hPa wind anomalies (vector, m s−1) during September for a increased (P1: 1992–1997 and P2: 2004–2010) and b reduced (N1: 1986–1991 and N2: 1998–2003) extreme rainfall in September over central India. Vectors with magnitude >0.2 m s−1 are shown for clarity.

In summary, our results indicate (1) since the 1980s, rapidly declining summer SIE in the KS region exhibits a more robust relationship with the frequency of ISMR extremes, compared to mean ISMR intensity; (2) extreme precipitation events in central India during the late phase of ISMR season can be explained by the combined effect of the upper atmospheric circulation anomalies resulting from reduced SIE in the KS region and low-level circulation anomalies over west-central India supported by warm SST anomalies in the north-western Arabian Sea. The extent of sea ice contribution to developing the large-scale upper-level circulation anomalies and their role in favouring ISMR extremes need to be studied in further detail with a combination of observation and modelling studies, given that they often diverge in conclusions on extra-polar impacts of Arctic sea ice changes7.

Methods

Identification of extreme rainfall events

The frequency of extreme events over central India is defined by a number of grid cells in central India (19oN–26oN; 75oE–85oE) with daily rainfall exceeding 150 mm day−1 for the respective time period of each year2. The intra-decadal variability of anomalies in frequency events is computed by removing the time mean (for 1980–2017) of frequency events from the values of individual years and then smoothing by a 5-yr running mean. The resulting time series is finally detrended and normalized to identify the episodes of increased (positive values) and decreased (negative values) frequency of extreme events.

The time series at the top right corner shows the variability in normalized 200 hPa geopotential height anomaly in August–September over the northwest Europe region (indicated by grey bars, 55oN:70oN, 10oE:50oE) and the subtropical East Asian region (indicated by red line, 30oN:50oN, 90oE:130oE). The correlation between the detrended timeseries is 0.4 as indicated in left corner.

Eddy stream function, velocity potential

Eddy stream function (ψ) and velocity potential anomaly (\(\varphi\)) at 200 hPa are defined as

where \(u^\prime\) and \(v^\prime\) are zonal and meridional wind anomalies at 200 hPa level.

Data availability

The long-term multi-source SIE data is obtained from https://nsidc.org/data/G10010/versions/2. It provides the SIE records from 1850 onward until 2017. Sea ice concentration from Nimbus-7 SMMR and DMSP SSM/I-SSMIS passive microwave product is used for the period 1979–2017 (https://nsidc.org/data/NSIDC-0051/versions/1). The gridded daily ISMR data on 0.25o × 0.25o spatial resolution (http://www.imdpune.gov.in/Clim_Pred_LRF_New/Grided_Data_Download.html) is obtained from Indian Meteorological Department. All monthly mean atmospheric and oceanic variables are taken from ECMWF-ERA5 and ORAS5 datasets and obtained from https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/ and http://apdrc.soest.hawaii.edu/index.php, respectively.

Code availability

All the codes used here are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

01 July 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-021-00193-8

24 April 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-022-00257-3

References

Goswami, B. N., Venugopal, V., Sangupta, D., Madhusoodanan, M. S. & Xavier, P. K. Increasing trend of extreme rain events over India in a warming environment. Science 314, 1442–1445 (2006).

Roxy, M. K. et al. A threefold rise in widespread extreme rain events over central India. Nat. Commun. 8, 708 (2017).

Sharmila, S., Joseph, S., Sahai, A. K., Abhilash, S. & Chattopadhyay, R. Future projection of Indian summer monsoon variability under climate change scenario: an assessment from CMIP5 climate models. Glob. Planet. Change 124, 62–78 (2015).

Krishnamurti, T. N. et al. A pathway connecting the monsoonal heating to the rapid Arctic ice melt. J. Atmos. Sci. 72, 5–34 (2015).

Grunseich, G. & Wang, B. Arctic sea ice patterns driven by the asian summer monsoon. J. Clim. 29, 9097–9112 (2016).

Meleshko, P. V. et al. Sea Ice in the Arctic, Springer Polar Sciences. (Springer International Publishing, 2020).

Blackport, R., Screen, J. A., van der Wiel, K. & Bintanja, R. Minimal influence of reduced Arctic sea ice on coincident cold winters in mid-latitudes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 697–704 (2019).

Cohen, J. et al. Divergent consensuses on Arctic amplification influence on midlatitude severe winter weather. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 20–29 (2020).

England, M. R., Polvani, L. M., Sun, L. & Deser, C. Tropical climate responses to projected Arctic and Antarctic sea-ice loss. Nat. Geosci. 13, 275–281 (2020).

Overland, J. E. A difficult Arctic science issue: midlatitude weather linkages. Polar Sci. 10, 210–216 (2016).

Onarheim, I. H., Eldevik, T., Smedsrud, L. H. & Stroeve, J. C. Seasonal and regional manifestation of Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 31, 4917–4932 (2018).

Polyakov, I. V. et al. Long-term ice variability in Arctic marginal seas. J. Clim. 16, 2078–2085 (2003).

Johannessen, O. M. et al. Arctic climate change: observed and modelled temperature and sea-ice variability. Tellus Ser. A 56, 328–341 (2004).

Svendsen, L., Keenlyside, N., Bethke, I., Gao, Y. & Omrani, N. E. Pacific contribution to the early twentieth-century warming in the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 793–797 (2018).

Johannessen, O. M., Kuzmina, S. I., Leonid, P., Bengtsson, L. & Miles, M. W. Surface air temperature variability and trends in the Arctic. Tellus Ser. A 68, 1 (2016).

Goswami, B. N., Madhusoodanan, M. S., Neema, C. P. & Sengupta, D. A physical mechanism for North Atlantic SST influence on the Indian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L02706 (2006).

Krishnan, R. & Sugi, M. Pacific decadal oscillation and variability of the Indian summer monsoon rainfall. Clim. Dyn. 21, 23–242 (2003).

Sankar, S., Svendsen, L., Gokulapalan, B., Joseph, P. V. & Johannessen, O. M. The relationship between Indian summer monsoon rainfall and Atlantic multidecadal variability over the last 500 years. Tellus Ser. A 68, 1 (2016).

Gillett, N. P. et al. Attribution of polar warming to human influence. Nat. Geosci. 1, 750–754 (2008).

Screen, J. A., Simmonds, I., Deser, C. & Tomas, R. The atmospheric response to three decades of observed Arctic Sea ice loss. J. Clim. 26, 1230–1248 (2013).

Rajeevan, M. & Sridhar, L. Inter-annual relationship between Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies and Indian summer monsoon. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, L21704 (2008).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Blackport, R. & Screen, J. A. Insignificant effect of Arctic amplification on the amplitude of midlatitude atmospheric waves. Sci. Adv. 6, (2020).

Zhang, R. et al. Increased European heat waves in recent decades in response to shrinking Arctic sea ice and Eurasian snow cover. npjClim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 7 (2020).

Gong, D. Y. et al. Interannual linkage between Arctic/North Atlantic Oscillation and tropical Indian Ocean precipitation during boreal winter. ClimDyn 42, 1007–1027 (2014).

Rinke, A., Maslowski, W., Dethloff, K. & Clement, J. Influence of sea ice on the atmosphere: a study with an Arctic atmospheric regional climate model. J. Geophys. Res. 111, D16103 (2006).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Acknowledgements

Richard Davy and Raghu Murtugudde is acknowledged for helpful discussion and valuable comments during the course of the study. S.C. thanks Snehlata Tirkey, and Subeesh MP for their help and useful discussions during the study. NCPOR is an autonomous institute fully funded by the Ministry of Earth Sciences, Govt. of India. This is NCPOR Contribution number J-17/2021-22 and the framework of Research and Development Program of the Korea Institute of Energy Research(KIER) (C2-2409).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. conceived the idea in discussion with M.R., N.M., and R.P.R. S.C. performed the data analyses and wrote the initial manuscript. O.M.J. contributed substantially in improving the research and presentation. Figures: S.C., R.P.R. Writing, editing, presentation and reviewing: all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chatterjee, S., Ravichandran, M., Murukesh, N. et al. A possible relation between Arctic sea ice and late season Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall extremes. npj Clim Atmos Sci 4, 36 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-021-00191-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-021-00191-w