Abstract

Earth’s high latitudes are projected to experience warmer and wetter summers in the future but ramifications for soil thermal processes and permafrost thaw are poorly understood. Here we present 2750 end of summer thaw depths representing a range of vegetation characteristics in Interior Alaska measured over a 5 year period. This included the top and third wettest summers in the 91-year record and three summers with precipitation close to mean historical values. Increased rainfall led to deeper thaw across all sites with an increase of 0.7 ± 0.1 cm of thaw per cm of additional rain. Disturbed and wetland sites were the most vulnerable to rain-induced thaw with ~1 cm of surface thaw per additional 1 cm of rain. Permafrost in tussock tundra, mixed forest, and conifer forest was less sensitive to rain-induced thaw. A simple energy budget model yields seasonal thaw values smaller than the linear regression of our measurements but provides a first-order estimate of the role of rain-driven sensible heat fluxes in high-latitude terrestrial permafrost. This study demonstrates substantial permafrost thaw from the projected increasing summer precipitation across most of the Arctic region.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arctic amplification has caused enhanced warming in Earth’s Polar Regions compared to lower latitudes1,2. Commensurate with this are projections for a year-round increase in precipitation3,4,5 that is expected to be greater than at lower latitude locations6. Recent studies have already reported increased summer (wet) precipitation in the Arctic7,8,9 and this is projected to continue in the future6,10,11. The fraction of wet (liquid) to dry (snow) precipitation is also projected to increase as the summer season lengthens6,12. Increases in projected Arctic summer precipitation are larger under high emission and warming scenarios than for lower emission scenarios13.

It is clear that increased Arctic summer precipitation will influence hydrologic processes14 and the soil thermal regime15 of the permafrost that underlies 24% of the northern hemisphere. Permafrost soils contain large carbon stores (twice what is currently in Earth’s atmosphere) and permafrost, when kept frozen, provides stable ground surface conditions for infrastructure. Increased rainfall has recently been linked to methane release from thawing soils16. Changes in snow conditions and liquid water are known to affect the permafrost thermal state though some aspects of heat transfer (latent heat) are better understood than others (advective heat transport)17. Most of the studies linking precipitation to permafrost thaw have focused on an increasing winter snowpack that provides thermal protection against winter cold18,19,20. Relationships between the depth of the seasonally thawed “active layer” and increasing rainfall have been documented in a few studies21,22, but how these relationships vary over time, space, or a changing precipitation regime in northern ecosystems is poorly understood.

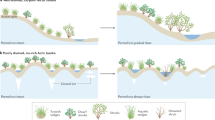

In permafrost terrains, the seasonally thawed active layer depth is controlled by local climate, vegetation and soil properties, hydrology, topography, and the timing and thermal conductivity of the previous winter season snowpack23. In terrains with near-surface permafrost, the seasonal thaw front moves downward throughout the summer, so end of summer season surveys represent the maximum active layer extent24. In many locations the permafrost is “ecosystem protected” against summer thaw by the local vegetation cover and soil and this provides resiliency against top-down thaw or disturbance25,26. Most of the studies linking vegetation to permafrost thermal protection have focused on the thermal conductivity or albedo of the vegetation represented. These studies report tussock vegetation27 and areas with thick Sphagnum moss or well-developed surface organic layers28 provide the strongest protection against seasonal thaw and permafrost degradation. Deciduous forests, soils with low organic matter or low ice content, and areas where surface vegetation has been disturbed by fire or human activities provide the least protection against surface thaw29,30. A key knowledge gap remains in our ability to project how (and where) these surface properties regulate the sensitivity of permafrost to changes in the type and amount of precipitation.

Here we explore the relationships between anomalously wet summers and thaw depth using 2750 end of summer active layer thickness measurements at a variety of locations in discontinuous permafrost near Fairbanks, Alaska (Fig. 1). Our measurements were taken between 2013 and 2017 at four sites along transects representing a variety of vegetation cover types (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Measurements were repeated in the same exact locations every year to allow us to detect permafrost change and minimize spatial variation in active layer depth attributable to soil microform or vegetation structure heterogeneities. Our active layer measurements represent a diverse set of vegetation, including tussock tundra, black spruce forest with Sphagnum, mixed deciduous forest, wetlands, and disturbed areas. The measurements on trail crossings, clearings, and other disturbed locations allow us to examine the sensitivity of pristine versus disturbed permafrost to changing precipitation patterns. In total, the five terrain types in our study areas represent ~70% of the land cover present in the boreal and taiga of the Arctic31. We modeled our active layer depth measurements using summer rainfall and ecosystem type as fixed effects and compared these to parameters commonly attributed to seasonal thaw depth in permafrost terrains: snowfall, summer mean temperature, summer heating degree days, the previous year’s active layer depth, and the volumetric and gravimetric moisture content of active layer and permafrost soil.

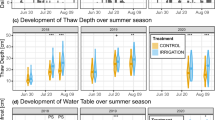

Our measurement period represented two summers with wet (i.e. liquid) precipitation amounts close to the 18.5 cm per summer mean over the 91-year record, one slightly drier summer, and two summers representing the most (2014; 37 cm cumulative precipitation) and third most (2016; 33 cm cumulative precipitation) wet precipitation totals measured in the 91-year meteorological record for the area (Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 1). The 2014 summer was unique because it included eight of the top one hundred 24 h wet precipitation totals in the 91-year record but the least cumulative precipitation in the period between May to mid-June of the 5 years we analyzed. For example, the first major rainfall in 2014 did not occur until mid-June and half of the precipitation fell during large events between mid-June and early July. Major flooding, surface runoff, and ground inundation at our sites started in mid-June and lasted throughout the summer, particularly in tussock tundra ecotypes. The other wet summer captured by our study (2016) yielded only one of the top one hundred 24 h wet precipitation totals. In contrast to 2014, in 2016 numerous rainfall events started in mid-May and continued more consistently throughout the summer. There was standing water at some field locations but not nearly as much inundation and flooding as was evident in 2014. This is likely because the 2016 summer had fewer major rain events and far more frequent smaller ones. Thus, despite a similar amount of precipitation in the summers of 2014 and 2016, the 2016 summer experienced more consistent flux of wet precipitation to our field sites over a far longer period of time. There was little to no inundation or standing water at the field sites in 2013, 2015, or 2017. Neither 2013 nor 2015 had any 24 h wet precipitation events that were in the top one hundred for the area. 2017 had two top one hundred 24 h wet precipitation values but the total for that summer was only slightly above the mean.

Results

Wet precipitation and seasonal thaw of permafrost

Increasing summer rainfall led to enhanced permafrost thaw across all five ecotypes (Figs. 3 and 4, Supplementary Table 2). For example, the maximum active layer depth was closest to the surface in the driest summer (2013) and was considerably deeper in the two anomalously wet years (2014 and 2016). Across the entire measurement period increasing rainfall led to an average of a 0.7 ± 0.1 cm increase in active layer depth per cm of additional precipitation. The wet summers led to a steady increase in active layer depth between 2013 and 2017. Following the extremely wet summer of 2014, thaw depths did not return to 2013 values despite summers of 2015 and 2017 being similar in air temperature and wet precipitation totals. In addition, following the anomalously wet summer of 2016, the 2017 thaw depths were only slightly shallower, despite temperature and wet precipitation values in 2017 being closer to the long term mean.

Disturbed areas and wetlands showed the greatest absolute change in active layer depth, with 0.99 and 0.89 cm of additional active layer thaw per cm of rainfall, respectively (Fig. 5). It is apparent from the linear fit y-intercept values there is a wide variation in the typical mean active layer depth for the different ecotypes. For example, the disturbed ecotype y-intercept value of 65.5 cm is the deepest active layer while the tussock tundra value of 46.2 cm is the shallowest. This is likely because disturbed areas have limited ecosystem protection while tussock tundra has been reported to have the greatest ecosystem protection properties of our ecotypes27. Tussock tundra provides wetter soils, which conduct surface heat downward better than dry soils due to an increase in thermal conductivity from wetting of pore spaces in the soils32,33,34,35. Disturbed sites commonly exhibit subsidence following permafrost thaw29 and this promotes surface water ponding and, likely, additional thaw and associated subsidence. Though we made the thaw depth measurements in October, the sites were visited monthly during each of the summers. Both the wetland and disturbed ecotypes exhibited mostly dry surfaces during low precipitation summers but became inundated with standing water during the wet summers. These two ecotypes have limited forest cover (Supplementary Fig. 1) and thus low interception rates and potentially higher evaporation rates. There was also standing water in small localized low spots at the tussock shrub sites. However, the mixed forest and Sphagnum moss spruce forest had no visible standing water during our survey measurements. A possible explanation of why the low lying, low gradient areas exhibited the greatest rain-induced thaw is that the additional surface water that ponded in low lying areas migrated downward to warm the seasonally frozen and permafrost soils.

Data are categorized for 5 dominant ecotypes that vary in vegetation and soil properties, leading to variation in mean active layer depth (variation in y intercepts). Box and whisker plots of thaw depth versus total summer precipitation are provided for the five major terrain types. Upper and lower whisker lines denote the upper and lower 10% values, respectively. Box lines denote the upper 25%, median, and lower 25% values. Linear fit (black line) information is provided. The grayed area indicates the upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. Total summer rainfall × ecotype interaction: p < 0.001, F9, 2751 = 10.74.

Tussock shrubs have been found to provide the strongest ecosystem protection of the five ecotypes represented by our study areas and this is due to their thick organic layer and generally poor drainage properties25. At our study sites, tussock tundra yielded the shallowest active layer depths and the greatest relative increase in thaw depth in response to rainfall (0.75 cm of additional thaw per cm of an increase in rain). While wetlands and disturbed sites experienced a 25% increase in active layer depth between 2014 (the wettest summer) and 2013 (the driest summer), mean tussock tundra active layer depths were 51% deeper in 2014 compared to 2013. Tussocks grow on flat, low gradient surfaces over decadal to century time periods and provide strong ecosystem protection against summer thaw26. The tussocks at our study sites were surrounded by standing water during wet summer time periods, particularly in 2014 and 2016 (Supplementary Fig. 1, bottom left photo). This inundation and commensurate lateral flow of surface water provided long-term access to soil pore waters following rain events and likely increased sensitivity to rain-induced thaw at our tussock sites.

The other terrestrial environments, such as mixed forests and conifer forests with thick moss layers, had the least amount of thaw, yielding 0.56 cm and 0.25 cm of thaw per additional cm of rain, respectively. Standing water was extremely rare at these sites for two possible reasons. First, there was likely less throughfall due to interception by the thick canopy vegetation above the forest floor. Studies quantifying interception in boreal forest sites report interception rates range from 23% in spruce36 to 30% in larch37. Second, surface water was likely absorbed by the thick Sphagnum layer with large water storage capacity and upward water wicking through strong external capillary action38. The spruce-moss combination was the most resistant vegetation complex to thaw due to canopy shading as well as the strong thermal protection of Sphagnum moss and well-developed organic against summer thaw28. Due to these mechanisms our results highlight that these ecotypes are the most resistant to rain-induced thaw. A grid of 121 active layer depths since 2009 is available as a subset of the Farmer’s Loop site measurements. The area only represents moss spruce forest and a linear fit between active layer depth and summer mean temperature, cooling degree days, heating degree days, and total summer wet precipitation yields the greatest correlation of determination (0.53) for the relationship between active layer depth and mean summer wet precipitation.

We explored the effects of snowfall, summer mean temperatures, summer heating degree days, the previous year’s active layer depth, and volumetric and gravimetric moisture content (of both active layer and permafrost soil) on seasonal thaw depths. None of these relationships were related to active layer depth within or across ecotypes from 2013 to 2017. For example, 2016 (the third wettest year in the 91-year record) was the coldest summer in our measurement period, yet there were elevated thaw measurements across all land cover types. Four of the summers in our measurement period were warmer than the 91-yr mean summer temperature (11.8 °C) but only slightly (Supplementary Table 1). The lack of dependency between summer season thaw and winter precipitation, summer air temperatures, or the ice content of the seasonally thawed soils supports our interpretation that changes in active layer depths across our measurement period were driven predominantly by interannual variation in rainfall.

The projected future wetter and warmer conditions across most of the Arctic will trigger shifts in vegetation cover and disturbance regimes and this study demonstrates how land cover types govern relationships between summer precipitation and permafrost thaw. Human land use (roads, trails, and infrastructure) represents a much smaller proportion of disturbed landscape in the Arctic relative to wildfires, which combust the thermally protective surface organic mat and vegetation29 and accelerate thermokarst and degradation of ice rich permafrost39,40,41. Though our disturbed sites are not fire scars they represent areas where the surface vegetation (including protective moss and organic mats) has been removed and this is similar to what a high severity fire does. Conifer forests tend to be vulnerable to burning because they are largely comprised of plants with fire-adapted traits. Our study shows that permafrost in conifer forests is less sensitive to rainfall than in other ecotypes. Increasing fire severity is triggering vegetation state-changes away from conifer-dominated stands42 to disturbed or mixed forest ecotypes. Our results suggest increasing areas of disturbed, deciduous, or open (unforested) habitat could promote permafrost thaw under projected future wetter summer conditions. However, projecting how, where, and at what rate the changing high latitude precipitation regime will affect the thermal state of permafrost will require better physics based ecosystem models.

Estimating the thermal inputs associated with rain-induced thaw

To better parameterize the relationships between summer precipitation and the thermal state of permafrost we applied a simple energy budget model to calculate the amount of seasonal thaw attributable to the added heat from wet precipitation (see “Results” for more detail). We ask the question whether our measured increases in permafrost thaw are simply due to the thermal inputs of rain. Our first-order model is applicable because the end of summer season active layer depth represents an energy increment of latent heat and precipitation provides an added thermal energy input to the ground that causes thaw.

Our approach to estimating the added heat of precipitation is highly simplified and does not consider the full surface energy budget, for example, changes in incident solar or longwave radiation, which might be expected to covary with precipitation on a seasonal basis. Nonetheless, it provides a first-order estimate of the role of rain-driven sensible heat fluxes to our high-latitude terrestrial ecosystems. Estimated energy inputs by rain of ~10 MJ/m2 are approximately 20% of the reported magnitude of total summertime ground heat flux measured at the base of the active layer at sites in similar climates43. Estimated porosity (θ) values from the sites (Supplementary Table 3) are ~0.73–0.90 cm3 cm−3. This yields an estimate of the expected additional thaw increment per unit of rainfall of 0.15–0.24 cm thaw/cm rainfall. This is up to 4 times smaller than the observed linear correlation between rainfall and active layer thickness from our measurements (0.25–1.0 cm thaw /cm rainfall; Fig. 5), suggesting much of the variation in our measurements cannot be explained by 1-D thermal inputs of rain alone. However, our calculated estimate of the relationships between precipitation and thaw is approximately the same size response we measured for the conifer forest sites. One potential explanation for the differing magnitude and greater rates of observed thaw per increment of additional rainfall in wetter ecosystems may be due to surface and shallow subsurface water convergence. Lowland areas likely receive more water from higher in catchments and thus receive a commensurate increase in the heat transported by the water. As noted earlier, our lowland sites were flooded throughout most of the wet summers while the other ecotypes did not have evidence of the consistent and sustained presence of water at the surface. Thus, heat advection associated with lateral flow processes may dominate the vertical advection in such regions. This explanation would be consistent with our finding that the observed rates are best explained by the heat budget approach in upland (and less inundated) ecosystems.

Discussion

Following most disturbances in permafrost terrains, ice (massive ice or interstitial pore ice) in the permafrost melts and the volume change leads to ground surface subsidence. This, in turn, can lead to surface water inundation or shallow subsurface flow in low gradient locations, particularly in lowland landscapes. Our results suggest this process, along with increased summer precipitation, may cause a positive feedback to permafrost thaw and degradation. When permafrost degrades and the land subsides, this provides low lying areas on which water can pond and further thaw the permafrost soils. Though the low lying areas between tussocks are generally covered by the tall grassy shoots on top of the tussocks, ponded open water can lead to increased solar absorption which would, in turn, warm the ponded water. As stated earlier, our simple energy budget model did not adequately account for the potential that this ponding of surface and shallow subsurface water can provide a greater source of heat to thaw permafrost soils.

During the exceptionally wet seasons at our sites, it is likely that thaw encompassed the transition zone, a layer of high ice content soil that typically regulates surface permafrost temperatures because of the high latent heat required for it to thaw44. At our sites, the shallowest active layer depths were measured in 2013 and following the extremely wet summer of 2014 thaw depths similar to what was measured in 2013 were never repeated despite two other summers with relatively low summer precipitation similar to 2013. This suggests that at some or all of our sites the protective transition zone was thawed and did not re-form. It is likely the warming associated with elevated wet precipitation during one individual summer lasts for multiple years as the increased soil water content, particularly at the base of the active layer, provides a barrier to subsequent freezing in the next winter. These thermal memory effects may prime the system for continued thaw in the following summer(s).

Recent studies have suggested active layer deepening exposes reduced soil horizons to oxidizing conditions and mobilizes trace metals and nutrients (including the vast stores of permafrost carbon) out of soils and into rivers or streams or the atmosphere45,46. As a consequence, the deeper active layers at our sites from rain-induced permafrost thaw have major ramifications for the oxidation and reduction processes that govern the permafrost carbon cycle and the potential for trace metal mobilization from frozen soils. It is also clear abrupt thaw processes increasingly being identified across the Arctic47 are not well addressed by currently available ecosystem models, particularly with respect to precipitation controls on the permafrost thermal state and potential positive feedbacks between increased summer precipitation and top-down permafrost thaw or thermokarst development.

Methods

The field measurements for this study were made in the vicinity of Fairbanks, Alaska from 2013 to 2017 (Fig. 5). The area, part of the boreal biome, has a continental climate with a mean annual temperature of −3.3 °C and mean total annual precipitation of 28 cm of water equivalent48. Mean summer air temperatures have increased 2 °C since 1930 and are projected to increase an additional 1–2 °C by 204049.

Typically, mean daily air temperatures at the field sites remain above 0 °C from early May to early October (160 days). We made repeated thaw depth measurements each fall during the second week of October to represent the maximum depth of seasonal thaw (otherwise known as the “active layer depth”). Measurements were made every 4 meters along four linear transects. These included a 400 m transect “Farmer’s Loop 1” at 64.877N, 147.674W and a 500 m transect “Farmer’s Loop 2” at 64.874N, 147.677W. These two transects represent a variety of ecotypes including regions of mixed deciduous forest, wetland, tussock tundra, moss- black spruce forest, and some disturbed trail crossings. We also measured active layer depths within an 11 by 11 grid at a 4-meter spacing that was established in 2005 following previously established protocols for the Circumpolar Active Layer Monitoring (CALM) network (https://www2.gwu.edu/~calm). The site, CALM site 41, is located near the Farmer’s Loop transects at 64.876N, 147.667W and is located in a black spruce forest with 10–30 cm of Sphagnum moss cover. A 500 m transect was repeatedly surveyed at the Creamer’s Field migratory bird Refuge (64.868N, 147.738W) that crosses through mixed deciduous forest, tussock tundra, and some disturbed trail crossings. A 400 m transect was established above the CRREL Permafrost Tunnel in Fox (64.950N, 147.621W). Vegetation at this site is Sphagnum moss-black spruce forest with some 2–10 m wide disturbed clearings and trail crossings.

The 550 active layer depths were made each year at small numbered flags installed at each measurement location along the transects and inside the 121-point grid. The flags allow for the collection of repeat thaw depth measurements at the same exact location to ensure repeat measurements of vertically heterogeneous soil and vegetation features, particularly low lying areas, trail crossings and clearings, high centered polygons and their troughs, or tussocks. The location of each pinflag was surveyed for elevation, northing, and easting with a differential global positioning system (dGPS) at 10 cm accuracy.

We measured seasonal thaw depth using a 1 cm diameter graduated metal rod (“frost probe”) that extended to as much as 2.5 m in length. At each measurement location the frost probe was pushed downward into the ground to refusal to establish the distance between the ground surface vegetation and the ice-bonded base of the active layer/top of permafrost24.

An 8 cm diameter SIPRE corer was used to collect 2–3 m deep cores for volumetric ice content measurements at locations representing the major ecotypes at each site following established methods50. A Geoprobe 7822 Direct Push Technology track mounted drill rig was used to collect additional cores for gravimetric ice content measurements. Volumetric and gravimetric moisture contents from the cores are included in Table S1. In the 113 SIPRE core samples collected at our sites the soil porosities we calculate (using a particle density of 2.66) range from 76 to 90% (Supplementary Table 3). Using these porosities, the amount of wet precipitation for each summer, and the daily mean air temperature for each day that a rainfall event occurred in each summer we calculate values for the amount of additional thaw attributable to wet precipitation (Supplementary Table 4).

Statistical analyses were performed with the fit model application within the software program JMP version 13.0 (SAS Institute, Phoenix, Arizona). We modeled active layer depth using summer rainfall and ecosystem type as fixed effects and transect ID (location of each measurement) as a random effect to account for repeated measures. Results of this mixed effect model showed that the repeated measurements explained little variance in thaw depth and was not significant (Wald p = 0.66). Thus, for the remaining analyses, we utilized a general linear model (GLM) that included the fixed effects only. Results from the GLM show that the precipitation-thaw depth relationships varied by an ecotype interaction (Fig. 5). Within ecotypes, relationships varied in significance from the moss spruce forest (p < 0.001, t = −5.23), tussock tundra (p = 0.007, t = 2.69), wetland (p < 0.001, t = 11.51), disturbed (p = 0.09, t = −1.70), and mixed forest (p = 65, t = 0.45) ecotypes.

An estimate for the maximum total extra heat, Hrain, delivered to the base of the active layer, per unit of rainfall, over a given patch of ground is (in kJ/cm rainfall):

Where Cp is the heat capacity of water at constant pressure (4.1855 kJ kg−1 °C−1), ∆T is the difference in temperature (°C) between the rainfall and the soil at the base of the active layer, ρ is the density of water (kg/m3), and a is the area considered (m2). We assume soil at the top of the seasonal thaw layer at any given depth or time is isothermal (0 °C) and thus thawing the soil requires overcoming the latent heat of fusion and that the temperature of precipitation is equivalent to the mean air temperature during individual precipitation events. This ranged from 10.6 to 13.7 °C. There was no statistically significant relationship between air temperature and amount of precipitation within a summer season (Supplementary Table 1). We used the mean air temperature during all precipitation events for a given year for each summer of the five years we studied. Since the base of the active layer is, by definition at the freezing point, we assume it is 0 °C.

The extra heat required to deepen the active layer below a given patch of ground, HALD, by a given amount is (in kJ/cm thaw):

Where θ is the soil porosity (cm3 cm−3), Q is the latent heat of fusion of water (334 kJ/kg), and ρ and a are as described above.

If we assume that all of the energy delivered from the rainfall is balanced by thawing the soil, and that soils are always saturated at the base of the active layer, then we can calculate the extra thawing of frozen soil per unit rainfall as the ratio of the two terms, Hrain/HALD, which simplify to (in cm thaw/cm rainfall):

Supplementary Table 4 provides results from modeling the changes in thaw depth attributable to the thermal inputs of rainfall for each summer between 2013 and 2017. We assumed a 10% error associated with all measurement inputs to this calculation and propagated a cumulative error associated with this expected thaw depth value assuming Gaussian distributions.

Data availability

The datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

20 November 2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-00155-6

16 February 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-00155-6

References

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: a research synthesis. Glob. Plan. Change 77.1, 85–96 (2011).

Collins, M. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 1029–1136 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Zhang, X. et al. Enhanced poleward moisture transport and amplified northern high-latitude wetting trend. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 47–51 (2013).

Kattsov, V. M. et al. Simulation and projection of Arctic freshwater budget components by the IPCC AR4 global climate models. J. Hydrometeor. 8, 571–589 (2007).

Bintanja, R. & Andry, O. Towards a rain-dominated Arctic. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 263–267 (2017).

Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surv. Geophys. 35, 1175–1214 (2014).

van der Kolk, H. J. et al. Potential Arctic tundra vegetation shifts in response to changing temperature, precipitation and permafrost thaw. Biogeosci 13, 6229 (2016).

Fujinami, H., Yasunari, T. & Watanabe, T. Trend and interannual variation in summer precipitation in eastern Siberia in recent decades. Int. J. Climatol. 36, 355–368 (2016).

Kopec, B. G., Feng, X., Michel, F. A. & Posmentier, E. S. Influence of sea ice on Arctic precipitation. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 46–51 (2016).

Bintanja, R. & Selten, F. M. Future increases in Arctic precipitation linked to local evaporation and sea-ice retreat. Nature 509, 479–482 (2014).

Park, T. et al. Changes in growing season duration and productivity of northern vegetation inferred from long-term remote sensing data. Env. Res. Lett. 11, 084001 (2016).

Koenigk, T. et al. Arctic climate change in 21st century CMIP5 simulations with EC-Earth. Clim. Dyn. 1 11–12, 2719–2743 (2013).

Peterson, B. J. et al. Increasing river discharge to the Arctic Ocean. Science 13 298, 2171–2173 (2002).

Euskirchen, E. S. et al. Importance of recent shifts in soil thermal dynamics on growing season length, productivity, and carbon sequestration in terrestrial high‐latitude ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 12, 731–750 (2006).

Neumann, R. B. Warming effects of spring rainfall increase methane emissions from thawing permafrost. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 1393–1401 (2019).

Vincent, W. F., Lemay, M. & Allard, M. Arctic permafrost landscapes in transition: towards an integrated Earth system approach. Arct. Sci. 3, 39–64 (2017).

Payette, S., Delwaide, A., Caccianiga, M. & Beauchemin, M. Accelerated thawing of subarctic peatland permafrost over the last 50 years. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, 18 (2014).

Åkerman, H. J. & Johansson, M. Thawing permafrost and thicker active layers in sub‐arctic Sweden. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 19, 279–292 (2008).

Iijima, Y. et al. Abrupt increases in soil temperatures following increased precipitation in a permafrost region, central Lena River basin, Russia. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 21, 30–41 (2010).

Jorgenson, M. T., Shur, Y. L. & Pullman, E. R. Abrupt increase in permafrost degradation in Arctic Alaska. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, 2 (2006).

Kokfelt, U. et al. Ecosystem responses to increased precipitation and permafrost decay in subarctic Sweden inferred from peat and lake sediments. Glob. Change Biol. 15, 1652–1663 (2009).

Loranty, M. M. et al. Changing ecosystem influences on soil thermal regimes in northern high-latitude permafrost regions. Biogeosci. 15, 5287–5313 (2018).

Shiklomanov, N. I., Streletskiy, D. A., Little, J. D. & Nelson, F. E. Isotropic thaw subsidence in undisturbed permafrost landscapes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 6356–6361 (2013).

Shur, Y. L. & Jorgenson, M. T. Patterns of permafrost formation and degradation in relation to climate and ecosystems. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 18, 7–19 (2007).

Jorgenson, M. T. et al. Resilience and vulnerability of permafrost to climate change. Can. J. Res. 40, 1219–1236 (2010).

Chapin, F. S. III, Van Cleve, K. & Chapin, M. C. Soil temperature and nutrient cycling in the tussock growth form of Eriophorum vaginatum. J. Ecol. Mar. 1, 169–189 (1979).

Fisher, J. P. et al. The influence of vegetation and soil characteristics on active‐layer thickness of permafrost soils in boreal forest. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 3127–3140 (2016).

Brown, D. et al. Interactive effects of wildfire and climate on permafrost degradation in Alaskan lowland forests. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 120, 1619–1637 (2015).

Jafarov, E. E., Romanovsky, V. E., Genet, H., McGuire, A. D. & Marchenko, S. S. The effects of fire on the thermal stability of permafrost in lowland and upland black spruce forests of interior Alaska in a changing climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 035030 (2013).

Vogelmann, J. E. et al. Completion of the 1990s National Land Cover Data Set for the conterminous United States from Landsat Thematic Mapper data and ancillary data sources. Photogram. Engin. Rem. Sens. 67, 6 (2001).

Van Tatenhove, F. G. & Olesen, O. B. Ground temperature and related permafrost characteristics in West Greenland. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 5, 199–215 (1994).

Hinkel, K. M., Paetzold, F., Nelson, F. E. & Bockheim, J. G. Patterns of soil temperature and moisture in the active layer and upper permafrost at Barrow, Alaska: 1993–1999. Glob. Planet. Change 29, 293–309 (2001).

Harris, S. A. Causes and consequences of rapid thermokarst development in permafrost or glacial terrain. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 13, 237–242 (2002).

Ling, F. & Zhang, T. A numerical model for surface energy balance and thermal regime of the active layer and permafrost containing unfrozen water. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 38, 1–5 (2004).

Price, A. G., Dunham, K., Carleton, T. & Band, L. Variability of water fluxes through the black spruce (Picea mariana) canopy and feather moss (Pleurozium schreberi) carpet in the boreal forest of Northern Manitoba. J. Hydrol. 196, 310–323 (1997).

Hamada, S. et al. Hydrometeorological behaviour of pine and larch forests in eastern Siberia. Hydrol. Proc. 18, 23–39 (2004).

Goetz, J. D. & Price, J. S. Role of morphological structure and layering of Sphagnum and Tomenthypnum mosses on moss productivity and evaporation rates. Can. J. Soil Sci. 95, 109–124 (2015).

Liljedahl, A. K. et al. Pan-Arctic ice-wedge degradation in warming permafrost and its influence on tundra hydrology. Nat. Geosci. 9, 312 (2016).

Gibson, C. M. et al. Wildfire as a major driver of recent permafrost thaw in boreal peatlands. Nat. Comm. 9, 3041 (2018).

Lewkowicz, A. G. & Way, R. G. Extremes of summer climate trigger thousands of thermokarst landslides in a High Arctic environment. Nat. Comm. 10, 1329 (2019).

Johnstone, J. F. et al. Fire, climate change, and forest resilience in interior Alaska. Can. J. Res. 40, 1302–1312 (2010).

Juszak, I., Eugster, W., Heijmans, M. M. & Schaepman-Strub, G. Contrasting radiation and soil heat fluxes in Arctic shrub and wet sedge tundra. Biogeosci. 13, 404940–404964 (2016).

Shur, Y., Hinkel, K. M. & Nelson, F. E. The transient layer: implications for geocryology and climate‐change science. Permafr. Periglac. Proc. 16, 5–17 (2005).

Barker, A. J. et al. Late season mobilization of trace metals in two small Alaskan arctic watersheds as a proxy for landscape scale permafrost active layer dynamics. Chem. Geo. 381, 180–193 (2014).

Khosh, M. S. et al. Seasonality of dissolved nitrogen from spring melt to fall freezeup in Alaskan Arctic tundra and mountain streams. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 1718–1737 (2017).

Loiko, S. V. et al. Abrupt permafrost collapse enhances organic carbon, CO2, nutrient and metal release into surface waters. Chem. Geo. 471, 153–165 (2017).

Jorgenson, M. T., Racine, C. H., Walters, J. C. & Osterkamp, T. E. Permafrost degradation and ecological changes associated with a warming climate in central Alaska. Clim. Change 48, 551–579 (2001).

Douglas, T., Jones, M. C., Hiemstra, C. A. & Arnold, J. R. Sources and sinks of carbon in boreal ecosystems of interior Alaska: A review. Elem. Sci. Anth. 12, 2 (2014).

Douglas, T. A. et al. Degrading permafrost mapped with electrical resistivity tomography, airborne imagery and LiDAR, and seasonal thaw measurements. Geophys 81, WA71-WA85 (2015).

Acknowledgements

Funding for T.A.D. was provided by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center’s Army Basic Research (6.1) Program and the Department of Defense’s Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (projects RC-2110 and RC18-1170). We thank the numerous hearty people that helped with the frost probe and survey measurements.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.A.D. conceived the project and made the thaw depth measurements; M.R.T. oversaw the statistical analyses and C.D.K. performed the energy balance modeling; all authors analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Douglas, T.A., Turetsky, M.R. & Koven, C.D. Increased rainfall stimulates permafrost thaw across a variety of Interior Alaskan boreal ecosystems. npj Clim Atmos Sci 3, 28 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0130-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-020-0130-4

This article is cited by

-

Impact of permafrost degradation on the extreme increase of dissolved iron concentration in the Amur river during 1995–1997

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2024)

-

Linking drought indices to atmospheric circulation in Svalbard, in the Atlantic sector of the High Arctic

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Effects of extreme atmospheric precipitation on the stability of railways in the permafrost zone

Modeling Earth Systems and Environment (2024)

-

Past permafrost dynamics can inform future permafrost carbon-climate feedbacks

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Continentality determines warming or cooling impact of heavy rainfall events on permafrost

Nature Communications (2023)