Abstract

Ship engines in the open ocean and Arctic typically combust heavy fuel oil (HFO), resulting in light-absorbing particulate matter (PM) emissions that have been attributed to black carbon (BC) and conventional, soluble brown carbon (brC). We show here that neither BC nor soluble brC is the major light-absorbing carbon (LAC) species in HFO-combustion PM. Instead, “tar brC” dominates. This tar brC, previously identified only in open-biomass-burning emissions, shares key defining properties with BC: it is insoluble, refractory, and substantially absorbs visible and near-infrared light. Relative to BC, tar brC has a higher Angstrom absorption exponent (AAE) (2.5–6, depending on the considered wavelengths), a moderately-high mass absorption efficiency (up to 50% of that of BC), and a lower ratio of sp2- to sp3-bonded carbon. Based on our results, we present a refined classification of atmospheric LAC into two sub-types of BC and two sub-types of brC. We apply this refined classification to demonstrate that common analytical techniques for BC must be interpreted with care when applied to tar-containing aerosols. The global significance of our results is indicated by field observations which suggest that tar brC already contributes to Arctic snow darkening, an effect which may be magnified over upcoming decades as Arctic shipping continues to intensify.

Similar content being viewed by others

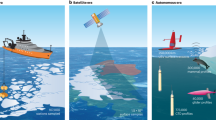

Introduction

Heavy fuel oil (HFO), a blend of the residual and distillate fractions of crude oil, is the most widely-used marine-engine fuel globally.1 Unburnt HFO is toxic; past HFO spills have caused substantial environmental damage that persisted for decades.1 Consequently, HFO was banned in the Antarctic region in 2012,1 but is still used across the rest of the open ocean, including the Arctic,2 where it represents 75% of the total marine-fuel mass.1 HFO combustion generates toxic particulate matter (PM) containing substantial amounts of heavy metals, polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs),3 and light-absorbing black carbon (BC).4 This BC is recognized as having substantial climate effects, which are expected to grow in light of retreating Arctic sea ice,2 and is therefore the focus of ongoing work commissioned by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) to inform future regulators.5

However, BC is not the only light-absorbing material in HFO-PM. Recent work has highlighted another, brown-colored form of light-absorbing, carbonaceous PM (LAC) with unknown chemical composition.4,6 This non-BC LAC was treated in those works as “soluble brown carbon” (soluble brC) in the conventional7,8,9 sense: a complex, liquid-like mixture of light-absorbing organic molecules that are volatilizable, miscible with non-light absorbing PM components such as organic aerosol, and soluble in common organic solvents. These properties imply a number of physical consequences, such as optical properties (and climate impacts) governed by internal mixing with non-absorbing PM,10 and justify the use of solvent extraction as a standard technique for studying brC.9

Insoluble LAC has a substantially different environmental fate to soluble brC. For example, insoluble LAC may accumulate on snow and ice surfaces during melt, absorbing sunlight and accelerating melt rates.11 Fundamental differences in physical properties also impact the interpretation of fundamental LAC measurements and treatment in model simulations.12 Insoluble LAC species include BC as well as the “tar ball” brC previously identified by electron microscopy in wildfire and biomass-burning samples,13,14,15,16,17,18 which has fundamentally different properties to both BC and soluble brC. It is therefore essential to understand the chemical nature of LAC in HFO-PM in order to predict its environmental impacts and atmospheric mixing state, and to develop analytical techniques suitable for its quantification.

Previous work4,6 on HFO-PM LAC has defined brC operationally, by attributing all infrared light absorption to BC and defining brC using deviations of the Absorption Ångström Exponent (AAE;19 the negative slope of a logarithmic plot of absorption coefficient babn(λ) against wavelength λ) from the value of 1.0 expected for BC.20 In this study, we identified the physical nature of this brC by combining a variety of analytical techniques. We found that this brC is comparable in nature to biomass-burning tar balls: it is insoluble in water and organic solvents, refractory, and absorbs in the near infrared, similarly to BC, but has a higher sp3/sp2 carbon bonding ratio and AAE than BC. We derive an optical model for this tar brC and show that it is the major light absorber in HFO-PM at low engine loads, even in the near infrared (NIR; λ ~ 1000 nm). The combination of properties we identify for HFO-PM tar brC means that the majority of common analytical techniques for quantifying airborne or in-snow LAC are substantially biased in its presence. Our results call for a refined classification of atmospheric LAC and the re-interpretation of multiple atmospheric-aerosol and snow-darkening-by-LAC studies.

Results

Four types of LAC

Atmospheric LAC has conventionally been separated into BC and brC.8,9,20,21 However, at least four LAC types must be distinguished in order to adequately describe the variety of LAC particles which have been observed in the atmosphere. We further divide BC into soot and char BC (which differ primarily in their morphology), and brC into tar and soluble brC (which differ primarily in chemical state), as discussed in the following. Our refined classification is shown in Fig. 1, which summarizes the tar brC properties measured in this study (first five rows; discussed below) and in the literature (see SI for a detailed description of each row).

Properties are sorted by their degree of overlap between LAC types. The ranges of continuous properties are plotted relative to soot BC (mean value) in the final column. Summary of key properties for the two black carbon (BC) and brown carbon (brC) species defined in the text. Properties are sorted by their degree of overlap between columns. EC, eBC, and rBC (colored text) refer to different analytical techniques for BC, of which only rBC is expected to distinguish BC from brC as discussed in the text. The morphology diagrams in columns 2–4 depict aggregated spherules, porous cenospheres, and solid spheres. Note that single-wavelength eBC measurements are typically extrapolated from red or NIR λ to visible λ using the AAE of soot BC (last 3 rows). This table combines literature data with experimental and modeling results from the present work, as cited in the main text and further described in the SI. “a”— Includes water, methanol, and acetone at room temperature, according to common practice in the literature. “b”—Apparent vapourization temperatures may be influenced by pyrolysis and are therefore related to the heating rate (see text). “c”—Typical count median Feret diameter (CMD) of externally-mixed particles. “d”—Values represent model particles at the given diameters (see Methods). “e”—Not applicable (n.a.) as canonical soluble brC does not absorb above ~600 nm

Soot BC is exactly that material defined by the seminal works of Bond et al.20 and Petzold et al.21 as “BC”. It (1) is strongly-light absorbing, (2) volatilizes at ~4000 K, (3) is insoluble in water and organic solvents, (4) exists as aggregates consisting of primary spherules with diameter 10–80 nm, and (5) consists primarily of graphitic sp2-bonded carbon. The small spherules comprising soot BC are formed via the in-flame nucleation of precursor compounds,22 and the graphitic-carbon domains comprising these spherules are curved into an onion-like structure due to the small spherule diameters. Soot BC typically has a wavelength-independent refractive index which, in combination with its typically open morphology and small size relative to visible/infrared wavelengths, means that it is a strong broadband absorber with AAE close to 1.0 when externally-mixed (Fig. 1).

Char BC fits all of the defining properties of soot BC except for its morphology. Char BC is formed when low-volatility fuel droplets (such as HFO) undergo surface graphitization rather than evaporation when heated.23 During this graphitization, the violent expansion of volatiles trapped within the droplet produces a highly-porous hollow sphere (cenosphere) of BC much larger than the original droplet (outer diameter ~1 μm).24,25 Due respectively to their size and specific surface area, char-BC particles may be expected to exhibit less curvature in their graphitic domains25 and slower oxidative reactivity26 than soot BC. However, the expected range of such properties for both char BC and soot BC are greater than the typical differences between the two,25,27 thus, carbon microstructure (property 5 above) does not robustly distinguish between these two sub-types.

Although char BC particles have been identified previously in the Arctic28 and over the Yellow Sea,29,30,31 previous definitions of atmospheric BC have not accounted for its unique morphology because of its rarity. Yet it is important to distinguish between char and soot BC for two reasons. First, due to its aerodynamic diameter being larger than that of soot BC, char BC will have a shorter atmospheric lifetime and will deposit faster onto the planetary surface. Second, micron-sized char BC has an AAE close to 0 (Fig. 1; see SI for details), substantially different from that of soot BC, such that any light-absorption-based measurement of BC will be biased in the presence of char. As we did not observe char BC in our study, such measurement biases are discussed further in the SI.

Soluble brC is the collection of substantially light-absorbing organic molecules in PM which are soluble in at least one solvent, such as water, methanol, and acetone, under standard conditions. Climate-relevant soluble brC absorbs light in the 300–600 nm range and is brown in color due to a strong wavelength dependence of absorption (high AAE).9 We have defined soluble brC in this manner to ensure equivalency with the majority of previous brC studies, where solvent extraction is frequently employed to characterize what is commonly referred to simply as “brC”.7,9,32,33 Note that solubility is fundamentally related to molecular surface area (in addition to polarity), and therefore to volatility,34 as discussed further below. Solvent extraction has become widespread in the analysis of brC because it allows both simple and powerful analytical techniques to be employed. This has led to the molecular identification of brC compounds, in particular, of oxygenated and nitrogenated aromatics (as predicted by Jacobson35) as the most likely absorbers of visible radiation in soluble brC from biomass burning9 and HFO combustion.36

Tar brC is the insoluble brC fraction (the difference between all brC and soluble brC). As insolubility is physically related to molecular size for aromatics,37 and since volatility decreases with molecular size,34 tar is expected to have an extremely low volatility. Larger aromatics absorb light more effectively,38 suggesting that tar brC will be more strongly absorbing than soluble brC. In addition, larger molecular sizes typically correlate with a higher carbon mole fraction (and fewer functional groups) for combustion-derived LAC, since thermal annealing during combustion leads to the elimination of hydrogen and oxygen and the fusing of aromatic rings.39 We describe tar brC as a subset of brC because the high AAE (>1) of tar brC may result in a brown color,40 although tar brC may be considered as a material with properties between those of BC and soluble brC. We have used the term “tar” for consistency with the term “tar balls” introduced by Pósfai and coworkers13,41 because we propose that these materials are of the same origin (as discussed below). To avoid ambiguity, we omit the “balls” except when discussing previous studies.

It must be emphasized that many of the LAC properties discussed above are continuous rather than discrete. Solubility is a continuous property by definition, tar brC viscosity and phase has been observed to vary upon atmospheric aging,42 and the ratio of sp2 to sp3 bonded carbon, used to define BC, may also vary smoothly. As we discuss in the optical-model section below, there therefore likely exists some overlap between tar brC and soot/char BC for certain key properties. This continuum of properties is hinted at by the order of the columns in Fig. 1, where, for example, the AAE decreases from right to left. The existence of such smooth transitions does not contradict the utility of the terms discussed above, because of the unique formation mechanisms of the different LAC types, but rather indicates that any classification of LAC must be done cautiously.

Operational definitions of BC also exist, which generally describe measurement techniques rather than conceptual classes. The simplest definition of BC is made by attributing light absorption at a given wavelength λ (typically red or NIR) to soot BC, yielding equivalent BC mass or eBC(λ).21 Another common diagnostic is thermal–optical analysis (TOA), which reports elemental carbon (EC) as the mass of carbon which is thermally refractory up to about 800 K (depending on the analysis protocol), after correcting for potential sample pyrolysis. Finally, laser-induced incandescence measures rBC as the incandescence signal of a PM sample after rapid heating to ~4000 K, and laser-vapourizer mass spectrometry measures the carbon fragments produced after a similar heating protocol.21 These definitions exploit different LAC properties and are therefore sensitive to different LAC fractions. We exploited these differences below to quantify the mass and optical properties of tar brC.

Operational definitions of brC have most commonly followed the solubility criterion which we incorporated into the soluble brC definition above. One alternative definition is optical-equivalent brC, defined by extrapolating eBC(NIR) measurements down to visible λ using the AAE (Eq. (1)), then subtracting predicted BC absorption from measured total absorption.6,9,33 This results in an optically-defined brC rather than a physical representation of LAC.6 Another definition compares PM light absorption before and after thermal denuding at ~600 K.9,10,43 This definition overlaps substantially with the definition of soluble brC, because volatilizable organic-PM molecules typically contain 4–30 carbon atoms and a wide range of polar functional groups32,44 and will consequently have a high solubility in polar and non-polar solvents.9 We experimentally evaluate this assertion for our data below. Note that we have focussed on solubility rather than volatility herein to avoid an important ambiguity with regard to volatility measurements: heating brC may not only lead to evaporation but also to pyrolysis. Pyrolysis rates are influenced by both heating rates and internal mixing of the PM, which may lead to substantial ambiguity in measurement interpretation, particularly for HFO-PM.45

Insoluble brC in HFO-PM

We initially hypothesized that HFO-PM brC absorbed at wavelengths λ > 600 nm due to the presence of the asphaltenes, the class of extremely-high molecular mass (~1000 u) aromatics,37 defined by their solubility in toluene but not n-hexane (or n-pentane, or n-heptane). We hypothesized this because asphaltenes are expected to absorb near-infrared light,37 as demonstrated for our HFO sample in Fig. 5a, and because multiple soluble molecules found in HFO fuel have also been detected in HFO-PM.36,46

To test this hypothesis, we performed stepwise solvent extraction of four HFO-PM filter samples, measuring the sample absorption after each step. The results for a representative filter are shown in Fig. 2a, and in more detail in Supplementary Figure 1. The AAE(375,850) values in the figure were calculated using19

where AAE(λ1, λ2) denotes the AAE calculated from two wavelengths in nanometers. The AAE(375,850) of our HFO-PM filter samples was initially 1.7. After water extraction, the AAE did not decrease substantially. Furthermore, the AAE remained constant after hexane extraction, and after toluene extraction (Fig. 2a). Mass spectra of the solvent-extracted filters taken during TOA showed that virtually all volatile organic PM had been extracted (discussed further below). We therefore reject our initial hypothesis that asphaltenes were responsible for brC absorption in HFO-PM.

Solvent extraction of HFO PM. a Both untreated and solvent-extracted particulate matter (PM) samples from a marine engine operated on heavy fuel oil (HFO) had an AAE(375,850) of 1.7, showing that the major brC species in HFO-PM was insoluble in water, hexane, and toluene. b The insolubility of HFO-PM brC is unique in comparison to the data set of Kirchstetter et al.7 c (inset) “Tar brC”, qualitatively identified in our samples using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), was therefore the major brC species in HFO-PM. Note that no char BC was observed by SEM. The black circles in the micrograph are pores in the polycarbonate filter. Error bars represent the propagated standard error of the mean

These experiments also rule out multiple alternative hypotheses. Specifically, they rule out the hypotheses that our observed high AAE was caused by (i) internal mixing of BC with soluble brC or other PM; (ii) bathochromic shifts of soluble brC absorption due to surface adsorption47 or metal complexation;48 (iii) electronic interactions between molecular aggregates in solution;9 and (iv) pH effects on soluble brC absorption.49 All of these effects would be nullified by solvent extraction. Similarly, separate measurements of vanadium (the major trace metal in HFO-PM and in our samples50) emission factors did not correlate with the AAE(370,880) (Supplementary Figure 2), ruling out the possibility that inorganic species contributed significantly to our observed HFO-PM light absorption.

To place our results in the context of literature, Fig. 2b plots our measurements against those of Kirchstetter et al.,7 who measured the AAE of filter samples before and after acetone extraction for a variety of biomass-burning and traffic-related sources. Their reported AAEs represent variable wavelength ranges, with a minimum λ of 330–450 nm and a maximum λ of 850–1000 nm. Figure 2b also includes the line y = x − 1, representing the expected trend if their samples were of soot-BC (expected AAE = 1) mixed with soluble brC (AAE > 1). As seen in the figure, all of the Kirchstetter et al. samples followed that trend, whereas none of our samples did. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of such an inconsistency and the first demonstration of a PM sample where the major brC fraction was insoluble.

Tar brC identification using SEM

Having shown that the brC species in HFO-PM was insoluble, we performed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of sub-2.5 μm PM samples to identify which of the LAC types described above were present in HFO-PM (see SI for further discussion). We found that both tar brC (Fig. 2c) and soot BC (Supplementary Figures 3 and 4) were present in our samples. Char BC, which may be readily identified using SEM due to its unique morphology and size (Fig. 1), was absent in our samples.

Refractory nature of tar brC

We acquired two independent data sets to investigate the refractory nature of tar, using (i) high-resolution aerosol mass spectrometry (HR-AMS) with two separate vapourization techniques6 and (ii) TOA51 in combination with resonance-enhanced multi-photon ionization (REMPI) mass spectrometry.46

Using HR-AMS, we flash-vapourized HFO-PM particles directly from the aerosol phase by impaction onto an 873 K tungsten surface. The resulting vapors were analyzed by electron-ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry, yielding a mass spectrum in which the elemental composition of 483 ions with m/z from 12 to 150 was identified (see SI for details). We compared the HR-AMS mass spectra of HFO-PM with that of two distillate fuels, diesel and marine-gas-oil PM, which both contained negligible amounts of brC (as discussed elsewhere6), and found no substantial difference between the carbon-containing peaks of the three fuels (Supplementary Figure 5). Similar results for these same PM samples were found using proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometry in combination with a 470 K vapourizer.52 Since no mass spectral differences were observed in spite of the fact that no brC was present in the distillate fuels, we conclude that the brC species in HFO-PM did not flash vapourize on the 873 K surface, that is, the brC was refractory.

Using the “IMPROVE-A” TOA protocol,51 we found that the solvent-extraction experiments presented in Fig. 2 removed virtually all of the carbon evolving at the first two temperature stages (OC1 and OC2) from the filter (Supplementary Figure 6). Substantial signals remained at the later OC3 and OC4 stages, which is not unexpected since these fractions include pyrolytic species.46 The EC mass measured on the filters was also lower after solvent extraction, due to the reduction of pyrolysis and sulfate-related biases in HFO-PM.45 All EC concentrations reported herein are therefore based on solvent-extracted measurements. Based on previous reports of refractory tar brC in biomass-burning samples,41,53 we anticipated that these EC concentrations correspond to the sum of soot BC and tar brC in HFO-PM. Note that pyrolysis during TOA is related to its slow heating (the maximum heating rate is ~7 K min−1, with wait times programmed at each stage), compared with the HR-AMS, which heats particles much faster and is not designed to observe slowly-evolved species.

Our interpretation of the TOA data is further supported by the REMPI mass spectra of the molecules evolved during TOA (Supplementary Figure 7). The REMPI technique is specifically sensitive to aromatics, and primarily detected the evolution of smaller molecules during the higher-temperature (OC3 and OC4) stages compared to the lower-temperature (OC1 and OC2) stages, particularly for the solvent-extracted filter samples, which is a clear indication of pyrolysis.

Carbon bonding in HFO-PM tar

We employed Raman spectroscopy in order to characterize the bonding state of tar carbon in our samples of untreated and solvent-extracted filter samples. Figure 3 shows the results, in the context of the Raman spectra of more- and less-graphitic flame soot.54 All spectra were normalized to the major Raman band at ~1350 cm−1. After solvent extraction, the Raman intensity at 1100–1300 cm−1 and ~1500 cm−1 was substantially lowered, while the relative height of the two major Raman bands was unchanged. These changes indicate the removal of soluble organic PM, which, as shown in Fig. 2a, did not influence the AAE and therefore did not remove the majority of the brC.

Raman spectra of HFO-PM before and after solvent extraction in comparison to the average Raman spectrum of two extreme types of flame soot (fuel-lean and fuel-rich), from Saffaripour et al.54 All spectra are normalized to the mode at ~1350 cm−1 and letters on the abscissa indicate the expected locations of the standard Raman bands (D4, D1, D3, G, D2). Solvent extraction primarily influenced the shoulder at ~1200 cm−1, which did not influence the AAE. The major difference between solvent-extracted HFO-PM and either soot spectrum is seen at ~1500 cm−1 and indicates a higher sp3/sp2 bonding ratio in the HFO-PM than in the flame soot

The Raman spectrum of the extracted-HFO-PM sample showed substantial differences to the flame-soot data. In terms of a five-band fit,55 these differences include a clearly higher D3/D1 peak-height ratio (corresponding to a relatively higher midpoint between the two major peaks, at ~1500 cm−1). This higher D3/D1 ratio indicates a higher ratio of amorphous carbon (disordered solid carbon with mixed sp2 and sp3 bonding) relative to graphite-crystalline-edge carbon,54 as is predicted for high-AAE carbon materials.39 In addition, either the G/D1 or the D2/D1 peak-height ratio, or both, was also higher for HFO-PM than for flame soot. As these two ratios appeared to change upon solvent extraction, we cannot follow common practice54 in attributing the G band signals to graphitic carbon, which is by definition insoluble. It is for this same reason that we have not attempted to quantify our spectra with five-band fits.

Optical properties of HFO-PM tar

While previous studies have reported increased brC emissions from HFO-PM combustion at lower engine loads,4,6 and have even reported apparent brC refractive indices by normalized optically-defined brC absorption (total absorption minus BC-predicted absorption) to organic PM concentrations,6 no previous study has directly estimated the mass and optical properties of the actual brC species in HFO-PM, that is, tar brC.

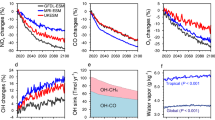

In order to gain insights into the optical properties of tar, we performed an experiment where the combustion conditions of HFO in the engine were varied using the crank angle at the start of fuel injection as a free parameter (Fig. 4). By varying this angle, we produced HFO-PM which was either dominated by soot BC or by tar brC, mimicking the engine-load impacts reported by Corbin et al.6 (discussed further below). More-negative start-of-injection angles correspond to higher maximum global gas temperatures inside the engine (Supplementary Figure 8), which may increase fuel-droplet pyrolysis and burnout, as well as increasing engine efficiency. Figure 4 compares rBC measurements obtained by a single-particle, laser-induced incandescence soot photometer (SP2) with TOA EC measurements, in the context of two AAEs calculated using Eq. (1), the AAE(370,950) and the AAE(880,950). Both AAEs varied from ~1.0 to ~2.0, with higher values at more-negative start-of-injection angles.

Formation of tar-rich (AAE ~2) or BC-rich (AAE ~1) PM in response to changing engine conditions. a The AAE(370,950) and AAE(880,950) both increased at more-negative start-of-injection angles, indicating the formation of a near-infrared-absorbing brC. b At more-negative angles, rBC concentrations fell to 0 while EC concentrations remained high. This indicates that rBC measured only soot BC, whereas EC measured both soot BC and tar brC, as illustrated by the trendlines. Error bars are propagated from the standard error of the mean of the measurements

When the AAEs were lowest, at approximately 1.0 (Fig. 4, least-negative crank angle), rBC concentrations were at their highest and the ratio EC/rBC was also 1.0. This indicates that soot BC was the primary LAC type in the HFO-PM. To corroborate this interpretation, we calculated the soot-BC AAE(λ, 950) at these conditions for six λ and report the result in Fig. 4. We also calculated the soot-BC mass absorption efficiency, MAE(λ) (Eq. (2)), as the ratio of absorption coefficient to rBC mass concentration at these conditions. The calculated soot-BC AAE(λ, 950) was approximately 1.0 at all λ and the soot-BC MAE(λ) was fully consistent with the MAE(λ) reported in the literature for this same engine for rBC from two control fuels which produced no brC (solid line), namely diesel and marine-gas-oil PM.6 The soot-BC calculations were also in excellent agreement with T-matrix model results for the computer-simulated soot aggregates described in Methods (solid black lines in Fig. 5) at all wavelengths.

Wavelength-dependent a AAE(λ, 950) and b MAE(λ) of BC and tar brC in HFO-PM. Error bars represent the propagated standard error of the mean. Symbols and lines indicate experimental and numerical results from this study, respectively; shading indicates literature data for context (refs. 11,12). The BC and tar brC AAEs and MAEs were retrieved from the data of Fig. 4 (see text for details); the unburnt HFO data are for a toluene solution and represent Rayleigh-regime particle sizes. Note that AAEs for unburnt HFO are AAE(λ, 900) and for biomass burning tarballs16 are AAE(λ, 780), which results in negligible differences to the reference AAE(λ, 950)

When the AAEs were approximately 2.0 (Fig. 4, most-negative crank angle), rBC concentrations were at their lowest and the ratio rBC/EC approached 0. This indicates that tar brC absorption dominated overall LAC absorption, since BC-dominated PM has AAE of 1.0 and since EC includes both BC and tar.53 To provide a conservative estimate of the tar AAE(λ, 950) and MAE(λ), we estimated tar absorption coefficients by subtracting BC absorption (the product of rBC mass concentration measured at these conditions with the soot-BC MAE(λ) described above) from the total (Eq. (3)). Tar AAEs(λ, 950) were then calculated using Eq. (1), and were in the range 3–6 for λ of 370–1000 nm, substantially higher than the AAE(λ, 950) of 1.0 for soot-BC. Further, we estimated tar mass concentrations as the difference of EC and rBC (Eq. (4)), and normalized these absorption coefficients by the tar mass concentration to obtain MAEs(λ) of tar brC (Fig. 5). Note that we have not addressed internal mixing here because a previous study of HFO-PM from this engine showed that BC was externally mixed.6

The tar MAEs were substantially higher than those of soluble brC, and at 520 nm were 2.6 ± 1.3 m2 g−1 compared to 9.9 ± 1.1 m2 g−1 for soot BC. Figure 1 includes this tar MAE as a lower limit (mean minus standard error) and the upper bound reported by Alexander et al.15 (4.1 m2 g−1), which is higher than our estimated upper bound, to emphasize the expected variability between tar brC samples discussed below. In spite of this variability, tar MAEs may be generally considered as significantly higher than typical soluble-brC MAEs, as shown by the Sun et al.32 data in Fig. 5.

Optical model of HFO-PM tar

In this section, we construct an optical model of the properties of tar based on its chemical origin and demonstrate that this model adequately describes our tar brC samples.

It has been shown that the thermal annealing of HFO droplets produces tar-like material as an intermediate step towards char-BC formation56 and subsequent oxidation. This annealing process corresponds to the elimination of hydrogen and oxygen, the fusing of aromatic rings, and thereby the formation of a partially-graphitized material. The thermodynamic limit of this process is the formation of graphitic material (or, in the presence of oxygen, oxidation to CO2). However, as certain materials are kinetically (sterically) inhibited from achieving complete graphitization,57 the molecular composition of HFO may also play a role in tar formation. Our data suggests that two distinct pathways are involved in soot BC and tar formation, since rBC and tar concentrations were anti-correlated in Fig. 4. This result is in contradiction to the observation of Saleh et al.,10 that more-absorbing brC was emitted from biomass combustion under conditions where rBC emissions were relatively higher.

The context of graphitization provides physical insights into the question of why tar brC absorbs into the infrared. Larger aromatic systems have lower optical energy gaps, and therefore absorb at longer wavelengths.38 In terms of energy gaps, a continuum of graphitization can be envisioned where soluble brC (energy gap ~3–4 eV38) lies towards the limit of benzene and canonical soot BC (energy gap ~ 0 eV)39 lies towards the limit of graphene. As the Tauc energy-gap model has been proposed to describe this continuum,39,58 we have evaluated its applicability to our data. The Tauc model provides wavelength-dependent absorption coefficients given two parameters, an energy gap which influences the AAE, and a gap constant which scales the absorption coefficient (Eq. (5)).

We found that the HFO-tar data of Fig. 5 could be well described by an energy gap of 1.0 eV and a gap constant of 150 (cm2 g−1 eV−1)0.5 (red dashed lines in the figure). Utilizing the correlation between energy gap and H/C ratio reported by Minutolo et al.,58 this 1.0 eV corresponds to an H/C ratio of 0.65. Note that we have treated tar particles as lying in the Rayleigh-optics regime (<50 nm) for simplicity; Mie resonances may have increased their MAEs by ~20%. Our fitted energy gap for tar brC is substantially smaller than the 2.5 and 1.65 eV gaps utilized by Sun et al.32 to describe, respectively, soluble brC (shaded region in Fig. 5) and quenched-flame soot (not shown here). The smaller energy gap indicates larger aromatic moieties in HFO tar compared to those samples: tens of fused rings, rather than several rings.38

In addition to describing our current data, the Tauc model accurately describes light absorption by flame soot of varying maturity.58 This consistency supports the view that tar lies upon the continuum of graphitization at an intermediate position between small aromatic molecules (i.e., soluble brC) and graphene-like BC. It can therefore be anticipated that tar from different sources, or even engines, may display substantially different optical properties. To illustrate the range of possible properties for tar brC, we have included the wavelength-dependent measurements of Alexander et al.15 and Chakrabarty et al.16 in Fig. 5. Whereas the Chakrabarty et al.16 data are not significantly different from ours, the tar brC observed by Alexander et al.15 appears to be more mature than that observed in our study, according to its lower AAEs of ~2. Greater maturity is not only associated with lower AAEs (closer to 1.0) but also with larger MAEs,58 consistent with the MAEs we calculated from the Alexander et al.15 data being larger than our tar MAEs (Fig. 5). Finally, greater maturity is also connected to a more complete elimination of oxygen and hydrogen, consistent with the very low O/C of the Alexander et al.15 tar brC (0.04) compared to the data of Chakrabarty et al.16 (0.17), who reported higher AAEs than Alexander et al. (Fig. 5). We reiterate here that, due to its unique morphology, completely graphitized tar is not equivalent to soot BC.

For context, Fig. 5 also includes measurements of the MAE and AAE of unburnt HFO fuel in toluene solution. We note that even unburnt HFO absorbs substantially at higher wavelengths than conventional soluble brC.9,33 However, the HFO AAE is different from those of tar brC, showing a constant value of approximately 4.0 at all wavelengths. This difference highlights a fundamental compositional difference between HFO and tar. As discussed in the SI, we performed similar measurements of HFO fuel at various concentrations in toluene and also in tetrachloromethane, and obtained similar results, although CCl4 solutions of similar concentrations absorbed less intensely than toluene solutions.

Tar dominates HFO-PM light absorption at low engine loads

We observed that the AAE of HFO-PM increases as engine load decreases (Fig. 6). Figure 6a shows that the AAE(370,950) of HFO-PM increased from near unity (indicating that the majority of light absorption was due to BC) at high engine loads to greater than two at low engine loads (indicating that a large fraction of the light absorption was due to tar brC).

Tar brC emissions as a function of engine load. a The AAE(370,950) increased from ~1 to 2.2 as engine load decreased from 90 to 11%, corresponding to b PM dominated in mass by tar brC at low loads. c At 25% load, tar contributed over half of the total light absorption in the marine-engine exhaust, and would contribute even more at the lower loads used by vessels in the presence of ice

In order to relate the mass concentrations shown in Fig. 4b to the AAEs shown in Fig. 6a, we parameterized the observed correlations to estimate the average mass fraction of tar present at each engine load. Employing the tar MAEs described above, we then converted these mass fractions to absorption spectra. Figure 6c shows an example of the low engine load of 25%.

Figure 6c shows that over half of the total absorption at 25% load was due to tar, even at λ > 900 nm. As shown by the AAE(370,950), this fraction would be even higher at 11% load. As this increase occurred in spite of engine-load-independent rBC emissions (discussed elsewhere6), it indicates not only an increase in the relative importance of tar brC, but also an absolute increase in the emission factor of tar at lower loads.

It is important to place the load conditions in Fig. 6 in a practical context. While a marine engine will typically be tuned for higher engine loads, it may frequently be operated at lower loads for fuel economy.2 In our case, the engine was tuned for 50% load, under which conditions tar emissions were approximately 75% of the LAC mass (inferred from the mean AAE(370,950) being comparable to the 25% load case). Furthermore, ships traveling in the Arctic (except icebreakers) will typically operate at lower engine loads than normal when ice is present, for safety.2 Our results show that this would cause substantially enhanced emissions of tar, exposing Arctic ice to higher tar concentrations.

Biases in calculated light absorption for BC–tar mixtures

The measured refractoriness and optical properties of tar brC (see also Fig. 1) have important implications for measuring and modeling LAC in HFO-PM, which may be summarized as follows.

When a mixture of soot BC and tar brC is measured as eBC(λ) at the typical red or NIR wavelengths and extrapolated to shorter wavelengths using the AAE of soot BC, a negative bias (underestimation) in calculated light absorption will result, since the AAE of soot BC is lower than that of tar. When a mixture of soot BC and tar is measured as EC, a positive bias (overestimation) in calculated light absorption will result, since the MAE(λ) of tar is smaller than that of soot BC. When a mixture of soot BC and tar is measured as rBC, a negative bias in calculated light absorption will result, since laser-induced incandescence is not sensitive to tar according to our observations (Fig. 4).

In principle, only spectrally-resolved absorption coefficient (or eBC) measurements can avoid the abovementioned biases. When such measurements are too complex, the second-best method for estimating total light absorption by BC–tar mixtures is to measure eBC at λ close to the maximum solar insolation (~550 nm), which minimizes the resulting bias when absorption is extrapolated with an assumed AAE of unity.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that tar brC may be produced not only by biomass burning, but also by internal combustion engines operated on HFO. Multiple environmental data sets must be reconsidered in light of this fact. For example, Alexander et al.15 described highly-light-absorbing tar brC in East Asian outflow. Their samples did not contain potassium, a marker for biomass burning PM, and the authors could not attribute any source to them.15,31 As their samples were taken over the Yellow Sea of China, where HFO fuel is widely used in marine engines, and contained sulfur and silicon, which are both found in HFO,50,59 we propose that HFO combustion is the most likely source of those particles. Marine emissions are a major source of pollution over the Yellow Sea,60 and other studies have reported char-BC in that region29,30 (tar was not investigated in those studies), supporting this association.

In the Arctic, Xie et al.28 reported a greater number of amorphous-carbon particles than soot-BC particles based on electron microscopy, indicating that HFO-PM tar is likely an important LAC type in that region. This inference finds support in the high AAE of ~2 measured by Doherty et al.61 for water-insoluble LAC in Arctic snow, even in regions which were not impacted by biomass-burning. Such regions would have been locally impacted by HFO-PM, and HFO-PM is presently the only known source of insoluble brC other than biomass burning.

The fact that substantial evidence for the importance of HFO-PM tar in atmospheric samples can be identified in multiple separate environmental studies, without targeted analysis, supports the generalization of our results and suggests a substantial abundance of this previously-unidentified LAC type. The calculated light absorption and climate forcing of marine-engine emissions will be biased in the presence of tar, either high or low depending on the LAC-measurement technique as elaborated above. Future work must therefore seek to directly identify and quantify HFO-PM tar in environments impacted by marine-engine emissions, and regulators must ensure that light absorption by tar brC is accounted for in future legislation.

Methods

Experimental

Measurements were performed on a single-cylinder, four-stroke research diesel engine (1 VDS 18/15 CR) at the University of Rostock.3,46 The engine has a 150 mm bore and 180 mm stroke and operates at a nominal 1500 rpm with a maximum 80 kW output power. The fuel was used HFO180; its detailed physical properties have been reported previously.50 The layout of the engine represents a typical medium-speed large diesel engine. Complete details of the experimental setup for the BC and light-absorption instrumentation have been described previously.6,50 Briefly, rBC concentrations were measured by a single-particle soot photometer (SP2, DMT Inc., USA) calibrated with mass-classified BC particles. PM mass spectra were measured in real time using an Aerodyne High-Resolution Soot-Particle Aerosol Mass Spectrometer (Aerodyne Research Inc., USA) operated in dual vapourizer mode. The soot-particle vapourizer was a 1064 nm continuous-wave laser which vapourizes materials of sufficiently-high MAE(1064 nm).62,63 Our HFO-PM tar was not such a material, and was therefore not detected by SP-AMS (further details are provided in the SI). SEM was performed with a Hitachi SU350050 after coating samples with a 15 nm-thick Au film.

Thermal–optical analysis

Thermal–optical analyses were performed using a seven-wavelength analyzer, following the IMPROVE-A protocol.51 This protocol involves heating samples in helium in four temperature stages (393, 523, 723, and 823 K) before adding 2% oxygen to combust remaining carbon in three temperature stages (823, 973, 1073 K) (gray shading in Supplementary Figure 6). After solvent extraction, EC concentrations were a factor 0.55 ± 0.17 lower, indicating a substantial positive bias in EC, and reported EC concentrations were taken from or scaled to the solvent-extracted samples.

Optical properties

Light absorption coefficients babn(λ) were measured by two independent techniques. First, the offline multi-wavelength absorption analysis (MWAA) technique allowed calculation of the absorbance of a filtered PM sample from transmittance and reflectance measurements.64 Second, during this study, real-time measurements of light extinction and scattering at 780 nm with a cavity attenuation phase shift PM single-scattering albedo (CAPS PMSSA) monitor allowed the calculation of babn(λ) by subtracting scattering from extinction. The CAPS PMSSA data were used to calibrate a dual-spot aethalometer AE33,65 which measured babn(λ) in real time. This calibration resulted in a factor 2.6 reduction of the calculated absorption coefficients babn(λ) and is discussed extensively in Corbin et al.6

AAEs were calculated from either the MWAA or calibrated AE33 data using Eq. (1). The AAEs measured by MWAA and AE33 were in close agreement, as discussed by Corbin et al.6 MAEs were calculated from the mass concentration of an absorbing species CLAC as,

Light absorption by unburnt HFO

HFO absorption spectra were measured using a Hach DR3900 spectrophotometer. The spectrophotometer was calibrated using absorption standards available from the manufacturer. Multiple concentrations were measured, ranging from 4 to 100 mg/L, in order to rule out the hypotheses that light extinction by molecular aggregates contributed to the apparent absorption.37 We rejected this hypothesis as the normalized absorbance spectra obtained at 4 and 20 mg/L were similar; see the SI for further discussion on this topic. Data for the 20 mg/L spectra have been presented, as their signal-to-noise ratio was better. A typical asphaltene density66 of 1.2 g cm−3 was used to convert the measured absorption to the Rayleigh-regime MAEs reported in Fig. 5.

Filter extractions

Filter samples were extracted following a procedure designed to replicate the seminal results of Kirchstetter et al.7 First, filter absorbance was measured by MWAA. Then, filter punches were gently immersed in 5 ml of solvent and mechanically stirred for 60 min at 70 rpm using an Argo Lab SKO-D XL. The solvent was then decanted. This part of the procedure was performed thrice, first with 5 ml of solvent, then with 5 ml of solvent, and finally with 10 ml of solvent. The filter was then removed with clean tweezers and dried overnight in a silica-gel desiccator. Filter absorbance was then measured again.

The above procedure was repeated consecutively for three solvents on every sample: first with water, then with hexane, then with toluene. Three filters were analyzed, thus, nine extractions were performed in total. We note that this procedure is similar to the VDI standard 2465/1.67

Asphaltene extraction

The asphaltene fraction of our HFO sample was extracted following ASTM method D2007-93,68 substituting heptane with hexane.37 This procedure involves refluxing the HFO in hexane and washing the hexane-insoluble residue with toluene to obtain an asphaltene-in-toluene solution. The main difference between this ASTM method and the Kirchstetter et al.7 filter-extraction method is that the Kirchstetter procedure does not include refluxing at the hexane step. That means that some fraction of hexane-soluble material may have been removed by toluene rather than hexane. This difference has no impact on the interpretation of our results.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra of 14 individual particles were obtained with a commercial microRaman system (LabRAM HR, Horiba Jobin Yvon). Each spectrum is the average of 6 acquisitions of 20 s integration time. Samples were excited by 632.8 nm radiation at sufficiently low power (0.17 mW) with a 50× long working distance objective (Na = 0.55) to minimize heating effects. The energy range 646–2792 cm−1 was measured with 2 cm−1 resolution. Retro-reflected radiation is collected and passed through a notch filter that removes Rayleigh-scattered radiation.

Spectral baselines were subtracted by fitting a third-order polynomial to the 100 measurements about 750 and 2000 cm−1 before a five-band fitting procedure55 was used. Spectra were measured from the same quartz-fiber filters used for thermal–optical and MWAA analysis. The flame soot data in Fig. 3 represents the two most extreme conditions (most and least graphitic) of a commercial quenched propane-flame “CAST” burner, as reported by Saffaripour et al.54. We note that the results presented by Saffaripour et al.54 were obtained using the same analysis technique as used here.

Tar absorption coefficients and mass concentrations

As discussed in the main text, rBC mass concentrations measured by SP2, CrBC, reflected soot BC and not tar brC mass concentrations; whereas EC mass concentrations measured by TOA included both soot BC and tar brC.53 We therefore estimated tar absorption coefficients as

Correspondingly, we estimated tar mass concentrations as

These equations are discussed further in the main text.

LAC model calculations

The radiative properties of soot BC were calculated using the generalized multiparticle Mie (GMM) method69 for numerically generated fractal-like aggregates formed by monodisperse monomers in point contact. The aggregates were generated using a tunable cluster–cluster aggregation algorithm with fractal dimension and prefactor fixed at 1.8 and 1.3, respectively.70 The results were averaged over at least 3375 aggregate orientations. Monomer diameter was measured from TEM images as 30 nm.46 The number of monomers in the aggregate was chosen as 50 such that the aggregate mass was consistent with the median mass measured by SP2.6 Calculations were also performed for monomer diameters of 50 and 80 nm (with similar results, not shown) and monomer numbers of 1 to 600 (shown in Fig. 5). The AAEs shown in Fig. 7 are discussed in the SI.

We modeled char-BC properties using core–shell Mie theory for particles of air cores and BC shells. Mie theory provides an accurate representation of char cenospheres.71 The shell thickness was set by assigning an inner diameter that was 60% of the outer diameter (0.6 and 1.0 μm, respectively), as constrained by the data of Zhu et al.,31 but the results were not sensitive to this choice. The AAEs in Fig. 7 were produced using this model. For both soot and char BC calculations, a refractive index of 1.85 + 0.71i was used. Previous work20,72 has scaled up the MAEs calculated with this refractive index by 30% to agree with experimental data. We have performed a similar scaling, but rather than referencing literature we have referenced MAEs measured for BC from this engine during this measurement campaign,6 which were 48% larger than the standard literature value. A density of 1800 kg m−3 was used in all BC calculations.

We modeled soluble brC and tar brC properties using the Tauc model. The Tauc model relates the brC absorption coefficient to an energy gap Eg representing the energy difference between the lowest-energy unoccupied electronic state and the highest-energy occupied electronic state. The absorption coefficient babn for a photon of energy E(λ) is thus described as

where the parameter B is a constant. To represent soluble brC, we plotted Eq. (5) for B = 250 (cm2g−1eV−1)(1/2) and Eg = 2.5 eV, representing humic acids and water-soluble OM.32 To represent tar brC, we used the values stated in the manuscript. For simplicity we plotted this equation for brC particles in the Rayleigh regime (roughly, diameters below 100 nm), the MAE of larger, Mie-regime particles may be slightly (maximally about 20%) higher.

For soluble brC, we used a representative brC density73 of 1200 kg m−3. For tar brC, we used the mean density of 1500 kg m−3 reported by Alexander et al.15 For simplicity, we did not model the so-called Urbach tail, which reflects empirically-observed broadening of this curve at longer wavelengths32 nor the variability expected in the MAE of different soluble brC samples.9 These details, as well as the consideration of Mie effects, do not impact our discussion because typical soluble-brC absorption falls to 0 at λ of 400–500 nm.9,38

Data availability

Absorption-coefficient emission factors are available from the online database Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/record/2171915#.XF2-DlVKhhE. Related emission factors have been published in ref. 6 Further data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Lack, D. A. The impacts of an Arctic shipping HFO ban on emissions of black carbon. Report to the European Climate Foundation (2016).

Lack, D. A. & Corbett, J. J. Black carbon from ships: a review of the effects of ship speed, fuel quality and exhaust gas scrubbing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 12, 3985–4000 (2012).

Oeder, S. et al. Particulate matter from both heavy fuel oil and diesel fuel shipping emissions show strong biological effects on human lung cells at realistic and comparable in vitro exposure conditions. PLoS ONE 10, e0126536 (2015).

Mueller, L. et al. Characteristics and temporal evolution of particulate emissions from a ship diesel engine. Appl. Energy 155, 204–217 (2015).

International Maritime Organization Marine Environment Protection Committee. 62/24/4.20. Final Report of the Correspondence Group on Assessment of Technological Developments to Implement the Tier III NOx Emission Standards under MARPOL Annex VI (2011).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Brown and black carbon emitted by a marine engine operated on heavy fuel oil and distillate fuels: optical properties, size distributions, emission factors. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 123, 6175–6195 (2018).

Kirchstetter, T. W., Novakov, T. & Hobbs, P. V. Evidence that the spectral dependence of light absorption by aerosols is affected by organic carbon. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, D21208 (2004).

Andreae, M. & Gelencsér, A. Black carbon or brown carbon? The nature of light-absorbing carbonaceous aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 6, 3131–3148 (2006).

Laskin, A., Laskin, J. & Nizkorodov, S. A. Chemistry of atmospheric brown carbon. Chem. Rev. 115, 4335–4382 (2015).

Saleh, R. et al. Brownness of organics in aerosols from biomass burning linked to their black carbon content. Nat. Geosci. 7, 647–650 (2014).

Doherty, S. J. et al. Observed vertical redistribution of black carbon and other insoluble light-absorbing particles in melting snow. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5553–5569 (2013).

Gilgen, A., Huang, W. T. K., Ickes, L., Neubauer, D. & Lohmann, U. How important are future marine and shipping aerosol emissions in warming arctic summer and autumn? Atmos. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2017-1007 (2017).

Pósfai, M. et al. Atmospheric tar balls: particles from biomass and biofuel burning. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 109, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003JD004169 (2004).

Tivanski, A. V., Hopkins, R. J., Tyliszczak, T. & Gilles, M. K. Oxygenated interface on biomass burn tar balls determined by single particle scanning transmission x-ray microscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 5448–5458 (2007).

Alexander, D. T. L., Crozier, P. A. & Anderson, J. R. Brown carbon spheres in east asian outflow and their optical properties. Science 321, 833–836 (2008).

Chakrabarty, R. et al. Brown carbon in tar balls from smoldering biomass combustion. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 6363–6370 (2010).

China, S., Mazzoleni, C., Gorkowski, K., Aiken, A. C. & Dubey, M. K. Morphology and mixing state of individual freshly emitted wildfire carbonaceous particles. Nat. Commun. 4, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3122 (2013).

Hoffer, A., Tóth, A., Nyirö-Kósa, I., Pósfai, M. & Gelencsér, A. Light absorption properties of laboratory-generated tar ball particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 239–246 (2016).

Moosmüller, H., Chakrabarty, R. K., Ehlers, K. M. & Arnott, W. P. Absorption ångström coefficient, brown carbon, and aerosols: basic concepts, bulk matter, and spherical particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 1217–1225 (2011).

Bond, T. C. et al. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 118, 5380–5552 (2013).

Petzold, A. et al. Recommendations for the interpretation of “black carbon” measurements. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 8365–8379 (2013).

Wang, H. Formation of nascent soot and other condensed-phase materials in flames. Proc. Combust. Inst. 33, 41–67 (2011).

Schmidt, M. W. I. & Noack, A. G. Black carbon in soils and sediments: analysis, distribution, implications, and current challenges. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 14, 777–793 (2000).

Linak, W. P., Miller, C. A. & Wendt, J. O. Fine particle emissions from residual fuel oil combustion: characterization and mechanisms of formation. Proc. Combust. Inst. 28, 2651–2658 (2000).

Chen, Y., Shah, N., Braun, A., Huggins, F. E. & Huffman, G. P. Electron microscopy investigation of carbonaceous particulate matter generated by combustion of fossil fuels. Energy Fuels 19, 1644–1651 (2005).

Elmquist, M., Cornelissen, G., Kukulska, Z. & Gustafsson, O. Distinct oxidative stabilities of char versus soot black carbon: implications for quantification and environmental recalcitrance. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20, https://doi.org/10.1029/2005gb002629 (2006).

Vander Wal, R. L., Bryg, V. M. & Huang, C.-H. Aircraft engine particulate matter: macro-, micro- and nanostructure by HRTEM and chemistry by XPS. Combust. Flame 161, 602–611 (2014).

Xie, Z. et al. Summertime carbonaceous aerosols collected in the marine boundary layer of the arctic ocean. J. Geophys. Res. 112, https://doi.org/10.1029/2006jd007247 (2007).

Quinn, P. et al. Aerosol optical properties measured on board the Ronald H. Brown during ACE-Asia as a function of aerosol chemical composition and source region. J. Geophys. Res. 109, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003jd004010 (2004).

Clarke, A. et al. Size distributions and mixtures of dust and black carbon aerosol in Asian outflow: physiochemistry and optical properties. J. Geophys. Res. 109, https://doi.org/10.1029/2003jd004378 (2004).

Zhu, J., Crozier, P. A. & Anderson, J. R. Characterization of light-absorbing carbon particles at three altitudes in East Asian outflow by transmission electron microscopy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 6359–6371 (2013).

Sun, H., Biedermann, L. & Bond, T. C. Color of brown carbon: a model for ultraviolet and visible light absorption by organic carbon aerosol. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, https://doi.org/10.1029/2007gl029797 (2007).

Moschos, V. et al. Source apportionment of brown carbon absorption by coupling ultraviolet–visible spectroscopy with aerosol mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 5, 302–308 (2018).

Li, Y., Pöschl, U. & Shiraiwa, M. Molecular corridors and parameterizations of volatility in the chemical evolution of organic aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 3327–3344 (2016).

Jacobson, M. Z. Isolating nitrated and aromatic aerosols and nitrated aromatic gases as sources of ultraviolet light absorption. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 104, 3527–3542 (1999).

Sippula, O. et al. Particle emissions from a marine engine: chemical composition and aromatic emission profiles under various operating conditions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 11721–11729 (2014).

Mullins, O. C. The modified Yen model. Energy Fuels 24, 2179–2207 (2010).

Ruiz-Morales, Y. HOMO–LUMO gap as an index of molecular size and structure for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and asphaltenes: a theoretical study. I. J. Phys. Chem. A 106, 11283–11308 (2002).

Bond, T. C. Spectral dependence of visible light absorption by carbonaceous particles emitted from coal combustion. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 4075–4078 (2001).

Liu, C., Chung, C. E., Zhang, F. & Yin, Y. The colors of biomass burning aerosols in the atmosphere. Sci. Rep. 6, 28267 (2016).

Tóth, Á. et al. Chemical characterization of laboratory-generated tar ball particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 10407–10418 (2018).

Sedlacek, A. J. III et al. Formation and evolution of tar balls from northwestern US wildfires. Atmos. Chem. Phys. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2018-41 (2018).

Cappa, C. D. et al. Radiative absorption enhancements due to the mixing state of atmospheric black carbon. Science 337, 1078–1081 (2012).

Kroll, J. H. et al. Carbon oxidation state as a metric for describing the chemistry of atmospheric organic aerosol. Nat. Chem. 3, 133–139 (2011).

Lappi, M. K. & Ristimäki, J. M. Evaluation of thermal optical analysis method of elemental carbon for marine fuel exhaust. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 67, 1298–1318 (2017).

Streibel, T. et al. Aerosol emissions of a ship diesel engine operated with diesel fuel or heavy fuel oil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-016-6724-z (2017).

Hinrichs, R. Z., Buczek, P. & Trivedi, J. J. Solar absorption by aerosol-bound nitrophenols compared to aqueous and gaseous nitrophenols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50, 5661–5667 (2016).

Gavazov, K. B. Nitroderivatives of catechol: from synthesis to application. Acta Chim. Slov. 59, 1–17 (2012).

Phillips, S. M., Bellcross, A. D. & Smith, G. D. Light absorption by brown carbon in the southeastern United States is pH-dependent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6782–6790 (2017).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Trace metals in soot and pm2.5 from heavy-fuel-oil combustion in a marine engine. Environ. Sci. Technol. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.8b01764 (2018).

Chen, L.-W. A. et al. Multi-wavelength optical measurement to enhance thermal/optical analysis for carbonaceous aerosol. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 451–461 (2015).

Eichler, P. et al. Lubricating oil as a major constituent of ship exhaust particles. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 54–58 (2017).

Hand, J. L. et al. Optical, physical, and chemical properties of tar balls observed during the yosemite aerosol characterization study. J. Geophys. Res. 110, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004jd005728 (2005).

Saffaripour, M. et al. Raman spectroscopy and TEM characterization of solid particulate matter emitted from soot generators and aircraft turbine engines. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 51, 518–531 (2016).

Sadezky, A., Muckenhuber, H., Grothe, H., Niessner, R. & Pöschl, U. Raman microspectroscopy of soot and related carbonaceous materials: spectral analysis and structural information. Carbon 43, 1731–1742 (2005).

Ocampo-Barrera, R., Villasenor, R. & Diego-Marin, A. An experimental study of the effect of water content on combustion of heavy fuel oil/water emulsion droplets. Combust. Flame 126, 1845–1855 (2001).

Oberlin, A., Bonnamy, S. & Oshida, K. Landmarks for graphitization. TANSO 2006, 281–298 (2006).

Minutolo, P., Gambi, G. & D’Alessio, A. The optical band gap model in the interpretation of the UV–visible absorption spectra of rich premixed flames. Symp. (Int.) Combust. 26, 951–957 (1996).

Popovicheva, O. et al. Ship particulate pollutants: characterization in terms of environmental implication. J. Environ. Monit. 11, 2077–2086 (2009).

Lv, Z. et al. Impacts of shipping emissions on pm2.5 air pollution in China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 15811–15824 (2018).

Doherty, S. J., Warren, S. G., Grenfell, T. C., Clarke, A. D. & Brandt, R. E. Light-absorbing impurities in Arctic snow. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 11647–11680 (2010).

Onasch, T. B. et al. Soot particle aerosol mass spectrometer: development, validation, and initial application. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 46, 804–817 (2012).

Corbin, J. C. et al. Mass spectrometry of refractory black carbon particles from six sources: carbon-cluster and oxygenated ions. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 14, 2591–2603 (2014).

Massabò, D. et al. Multi-wavelength optical determination of black and brown carbon in atmospheric aerosols. Atmos. Environ. 108, 1–12 (2015).

Drinovec, L. et al. The “dual-spot” aethalometer: an improved measurement of aerosol black carbon with real-time loading compensation. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 8, 1965–1979 (2015).

Barrera, D. M., Ortiz, D. P. & Yarranton, H. W. Molecular weight and density distributions of asphaltenes from crude oils. Energy Fuels 27, 2474–2487 (2013).

Schmid, H. et al. Results of the “carbon conference” international aerosol carbon round robin test stage I. Atmos. Environ. 35, 2111–2121 (2001).

Liu, P. et al. Molecular characterization of sulfur compounds in Venezuela crude oil and its SARA fractions by electrospray ionization Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry. Energy Fuels 24, 5089–5096 (2010).

Xu, Y.-l. & Gustafson, B. Å. S. A generalized multiparticle Mie-solution: further experimental verification. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 70, 395–419 (2001).

Filippov, A., Zurita, M. & Rosner, D. Fractal-like aggregates: relation between morphology and physical properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 229, 261–273 (2000).

Huang, Y., Zhao, R., Jiang, J. & Zhu, K.-Y. Scattering and absorptive characteristics of a cenosphere. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 57, 63–70 (2012).

Bond, T. C. & Bergstrom, R. W. Light absorption by carbonaceous particles: an investigative review. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 40, 27–67 (2006).

Turpin, B. J. & Lim, H.-J. Species contributions to pm2.5 mass concentrations: revisiting common assumptions for estimating organic mass. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 35, 602–610 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Branka Miljevic, Nivedita Kumar, and the University of Rostock staff for their work and assistance during the measurements, and Greg Smallwood for useful discussions. The authors are grateful to Jonathan Taylor (University of Manchester) for providing the Mie code. J.C.C., M.Z., and M.G. were funded by the ERC under Grant ERC-CoG-615922-BLACARAT. J.C.C. was also funded by Natural Resources Canada under Grant EIP-EU-TR3-04A. This manuscript is part of the project WOOSHI, funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF, Project number 140590), the German science foundation (DFG, Grants Zi 764/5-1 and EC-OC-BrC ZI 764/7-1), and the Helmholtz Virtual Institute “HICE—Aerosol and Health” (www.hice-vi.eu) via the Helmholtz Association (HGF-INF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.C. and I.E.H. conceived the paper and J.C.C., H.C., I.E.H., and M.G. interpreted the data. D.M. performed the solvent extractions and MWAA analyses. H.C. performed the TOA analyses. F.B.M. and C.M. performed the SEM measurements. M.Z., M.G., and J.C.C. operated the SP2. A.A.M. and S.M.P. operated the SP-AMS. L.-L.T. performed the Raman analysis. G.J. operated the AE33 and provided its data. J.O. and S.M.P. coordinated the measurements and obtained the filter samples. B.S. operated and modeled the engine. F.L. modeled the soot aggregates. A.S.H.P. and R.Z. initiated and coordinated the study. J.C.C. analyzed all other data, prepared the figures, and drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Corbin, J.C., Czech, H., Massabò, D. et al. Infrared-absorbing carbonaceous tar can dominate light absorption by marine-engine exhaust. npj Clim Atmos Sci 2, 12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-019-0069-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-019-0069-5

This article is cited by

-

Microphysical properties of atmospheric soot and organic particles: measurements, modeling, and impacts

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2024)

-

Climate-relevant properties of black carbon aerosols revealed by in situ measurements: a review

Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2023)

-

Char dominates black carbon aerosol emission and its historic reduction in China

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Shortwave absorption by wildfire smoke dominated by dark brown carbon

Nature Geoscience (2023)

-

An overview of optical and thermal methods for the characterization of carbonaceous aerosol

La Rivista del Nuovo Cimento (2021)