Abstract

This paper uses the bibliometric method to analyze the basic characteristics and disciplinary knowledge structure of family-friendly policy research, as well as research hotspots and trends. The basic data source is the literature in the Web of Science Core Collection from 1985 to 2022. The following findings were obtained. First, the number of publications and citations in this field have increased exponentially, with scholars and research institutions from the US dominating the field of family-friendly policy research. Second, family-friendly policy research has been concentrated in the fields of management, sociology, and psychology, with a gradual trend toward cross-disciplinary integration, but a core group of authors has yet to be formed. Third, most of the family-friendly policy research has been conducted at the organizational level to explore the impact of family-friendly policies, with married women as the main research object. Finally, current family-friendly policy research focuses on policy fairness, childcare services, employee satisfaction, and work flexibility. Future research should focus on the dynamics of family-friendly policies and the empirical analysis of cross-level integration to improve the matching of policies with employee orientation. This study fills an analytical gap in the integration of family-friendly policies and scientometrics, proposes an expandable field of family-friendly policy research and research methods, and provides references and insights for future family-friendly policy research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As more and more countries usher in the era of aging and low fertility, the global population crisis is rampant. The low fertility problem has become a difficult problem affecting the balanced development of the global population in the twenty-first century. According to the “World Population Prospects 2022” released by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), the general decline in fertility rates has become the general global trend today, with the fertility levels in East Asia falling the most sharply. In the face of declining fertility and the risk of global population stagnation, many countries are working to provide more family-friendly policies to boost people’s fertility willingness and slow the decline in fertility rate. Family-friendly policies are a range of compensatory benefits and programs designed and implemented by companies to provide support and assistance to employees facing work-family conflict (Mekkaoui, 2010). It originated in Western welfare states and were originally implemented to help female employees balance work and family to alleviate the workforce reduction caused by declining fertility rates (Castles, 2003).

Family and work are the two most important areas of people’s lives. Work-family conflict is usually considered due to the competition between the two fields of work and family, making it difficult for employees to coordinate the needs between the two roles of work and family (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985). Influenced by the traditional concept of gender role division of labor, women have always been considered in almost all countries to undertake more family affairs (Jin and Chang, 2010). However, under the current trend of economic globalization, the market competition is fierce, and the labor participation rate of women is increasing around the world. As a result, simultaneously increased demand in both work and family domains exacerbated work-family conflicts among female employees (Whittock et al., 2003). In addition, previous organizational management policies were often designed from the perspective of male employees and did not take into account the dual responsibilities of female employees in terms of work and family, making it difficult to meet the needs of the growing number of female employees. Against this backdrop, family-friendly policies were developed continue to gain attention.

The family-friendly policies was designed to ease work and family conflicts among employees, so researchers have done a lot of research around the issue. Regarding individual employees, numerous studies have confirmed that work-family conflict has many negative influences on employee productivity, creativity, and work-life satisfaction (Frone, 2000; Jia et al., 2020) and is detrimental to the physical and mental health of employees and family harmony (Tang et al., 2020). This, in turn, affects organizational performance and turnover rates at an organizational level (Carr et al., 2008), which is not conducive to long-term organizational development. For society, the impact of work-family conflict on female employees is particularly pronounced (Aryee, 1992), as it is increasingly common for women with careers to get married later and have children later to avoid family matters affecting their career development (Harrison et al., 2020). This not only has an impact on women’s health (Cowgill et al., 2003) but also contributes to the decline in fertility rates in many countries. However, effective family-friendly policies can help employees mitigate work-family conflicts, which in turn can have a positive impact on employees’ well-being, innovative behavior, and family stability (Thomas et al., 1995; Castles, 2003). On the one hand, the accelerating urbanization process of recent decades has led to the shrinking of social networks and the continued decline of social support networks, which have strengthened the dependence of employees on their organizations (Weaver and Weaver, 2014). As the boundaries between organization and home have blurred (Peng-Wang et al., 2011), the importance of family-friendly policies for both organizations and employees has become increasingly evident. On the other hand, with social progress and economic development, the scope of family-friendly policies has been extended from married, single-parent employees with young children or elderly parents to all employees, including those who are single and have no caregiving responsibilities (Casper et al., 2007). The objectives of family-friendly policies have gradually expanded from alleviating work-family conflict for female employees to promoting work-life balance for all employees (Hammer et al., 2005).

After a start-up and growth phase, global family-friendly policy research has entered a phase of steady development. Among them, the steady development is mainly reflected in the increase of the number of relevant literature. However, core issues related to the existence of family-friendly policies, including conceptual definition and policy positioning, are still debated in academic circles (Bae and Skaggs, 2019; Masterson et al., 2021). In addition, this is despite the fact that family-friendly policies have proven to be effective in alleviating work-family conflict and helping employees balance work and family (Breaugh, 2004; Mumu et al., 2020), but the current practice of family-friendly policies around the world is not optimistic (Joecks et al., 2021). On the one hand, because the family-friendly policies of western welfare countries started early, and these countries generally have a well-developed system of public family policies, so the development of family-friendly policies in these countries has reached a bottleneck and has been relatively slow (Morgan, 2006). On the other hand, the family-friendly policies is developing rapidly for most developing countries. But, in practice, due to the influence of social environment factors such as social system, economic level, and cultural concepts, many enterprises in these countries are not very enthusiastic about family-friendly policies (Steven et al., 2003; Peng-Wang et al., 2011). Moreover, problems such as policy inequality, motherhood penalty, and obstruction of promotion are prevalent in the practice of family-friendly policies in these countries (Bao et al., 2021; Sangmook, 2008), and these problems greatly hinder the development of family-friendly policies. In this context, it is of great theoretical and practical importance to strengthen the research on family-friendly policies.

Bibliometric studies on work and family have only begun to emerge in recent years and are still relatively rare. Among them, Cassar et al. (2020) pointed out in a bibliometric study on work stress that work-family conflict is one of the main sources of employee work stress, and more interventions are needed to deal with it. Mumu et al. (2020) conducted a bibliometric study specifically in the field of work-family conflict to find research gaps in this field. Rashmi and Kataria (2021) used bibliometrics to review the literature in the area of work-family balance (WLB) published between 1998 and 2020 and found that family-friendly policies and practices that help balance employees’ work and family are research hotspot in this area. With the ever-increasing demands of work and life, the concept of work-life balance is shifting towards work-life integration (WLI), the success of which depends on the flexibility to perform duties. In this regard, Kumar et al. (2021) conducted a systematic literature review using bibliometrics to explore the concepts and relationships of work-life integration and flexible work arrangements (FWA). But scholars have not yet adopted a bibliometric approach to sort out, summarize and review the literature on family-friendly policies. The aim of this study is to use bibliometric analysis, combine with social network analysis, to provide researchers with a clearer, more comprehensive, and objective grasp of the development history, current situation, and future direction of family-friendly policy research. At the same time, it also provides a scientific basis for human resource management practice. Therefore, this study is not only conducive to promoting the progress of global family-friendly policy research, but also helping organizations to build family-friendly workplaces. In summary, our study focuses on the following questions:

-

What is the concept and content of family-friendly policies?

-

How has family-friendly policy research developed and what are the possible directions for future research?

-

What is the impact of family-friendly policies on employees, organizations and society? In particular, how does it affect work-family conflict?

Data and methods

In terms of data access, this study used the Web of Science Core Collection database for the literature search (sub-databases are SCI-E, SSCI, AHCI, and ESCI). This database is recognized by the international academic community and is the world’s largest journal citation index database, published by the Institute for Scientific Information (Singh et al., 2021; Martín-Martín et al., 2021). It contains over 21,100 peer-reviewed, high-quality scholarly journals published worldwide (ISI, 2000), covering the leading international academic journals that publish family-friendly policy research papers. And given the concentration and quality of the literature, only citation indexes in the humanities and social sciences field in the core collection of Web of Science are selected.

Before data collection, search term selection was first conducted. Usually, the search term is the target research area or an existing search definition. However, due to differences in both cultural and practical contexts, there is currently no uniform academic definition of ‘family-friendly policies’. In addition, no previous research has been conducted on family-friendly policies using bibliometric methods, so there was no search method available for this study. Therefore, this study draws on the search methods used by Chao Zhang and Jiancheng Guan (2017) in their study of “innovation and entrepreneurship ecosystems” and Kim and Chen (2015) in their study of “recommendation systems”. The search formula was compiled by summarizing the expressions of “family-friendly policies” in the classic books and literature published in top international journals in the field of family-friendly policy research. Four search terms were obtained: “family friendly polic*” (Allen, 2001), “family responsive polic*” (Glass and Estes, 1997), “family supportive polic*” (Butts et al., 2013), “work family polic*” (Kelly et al., 2008), “family friendly benefit*” (Allen, 2001), and “Family friendly practice*” (Joecks et al., 2021).

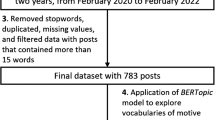

The specific search method is based on the “Topic” search method used by Chen et al. (2012) in their study of “regenerative medicine”, which allows for more representative and highly relevant literature. And considering the scientific nature of citation analysis and the limitations of software on citation types and languages, we only selected “Article” and “Review” in English document types for analysis (Okolie and Ogundeji, 2022). The results and specific methods are shown in Table 1. When using the selected retrieval formula for subject retrieval, some irrelevant results will inevitably be obtained (Alexandre et al., 2016). In order to make the obtained data more in line with the research theme, this study conducted manual screening, and screened out 4 obviously irrelevant categories with the research theme of “Official Household Residential Status”, “Female Reproductive Health”, “Filial Piety Scale for Chinese Elders” and “Gender Harassment” so that the literature accurately reflected the state of research in the field. Then use CiteSpace to remove duplicates based on this data. The specific data processing flow is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 571 “Articles” and 19 “Reviews” were obtained, totaling 590 documents, which were used as the sample for this study.

Literature review and bibliometrics are two important methods for exploring the knowledge framework of a field or discipline (Donthu et al., 2021). However, the existing literature on family-friendly policy reviews is relatively old, and these reviews only describe the current state of research on a specific topic of family-friendly policy up to a certain period (Bianchi and Milkie, 2010). It is impossible to fully describe and reveal the changes and trends of the overall picture, structure and content of family-friendly policy research. Bibliometrics is a method of quantitative research on literature, which has been widely used in many studies (Chen et al., 2014; Kim and Chen, 2015; Alexandre et al., 2016). It can overview a specific research field by depicting different types of network maps. It has played an important role in showing the research status of a certain field or discipline, identifying important journals and scholars in the field, outlining the knowledge structure of the discipline field, and tracking the dynamic evolution trend of the development of the field (Cobo et al., 2011). Therefore, it has been widely concerned and recognized by the academic community. Compared with the traditional review method of experts and scholars, the research method of bibliometrics has obvious advantages in these aspects (Chen et al., 2014; Kim and Chen, 2015; Alexandre et al., 2016): (1)The scope and time span of research using bibliometric methods is wider, and a larger amount of literature and related research topics can be included. (2)Bibliometrics are not limited by expertize and can help non-specialized researchers in the field better understand family-friendly policies. (3)Bibliometrics can mine more information in the literature. This study combines quantitative and qualitative methods in order to obtain more scientific and accurate research results. Specifically, this study adopts bibliometrics to analyze the external characteristics of the literature in the field of family-friendly policies, based on which the scientific knowledge map is used to further explore the research hotspots and frontiers in the field and ultimately form a research framework on family-friendly policies.

The knowledge mapping tool chosen for this study is CiteSpace (v.5.6 R5), developed by Chaomei Chen’s team at Drexel University in the US. CiteSpace is a software commonly used in bibliometric research (Cobo et al., 2011), which has been recognized by scholars and is widely used in many important studies (Chao and Jiancheng, 2017; Okolie and Ogundeji, 2022). CiteSpace is a Java-based visualization software designed to analyze the structure of knowledge and the dynamic evolution of hotspots through co-citation analysis, pathfinding network analysis, and collection clustering analysis of literature in a specific field to make reasonable predictions about the inflection point of knowledge and the continued development of the research field (Chen, 2006).

Results

Temporal and spatial distributions

In Fig. 2, there is a fluctuating trend of growth in the number of articles published on family-friendly policy research. The earliest literature on family-friendly policies retrieved from the WoS database was published in 1988, with the number of publications ranging from 3 in 1988 to 55 in 2022. Meanwhile, Fig. 3 shows a rapid increase in citations of the family-friendly policy literature, exploding from 2 in 1989 to 2,400 in 2022, and a total of 20,212 citations of the literature on family-friendly policies, reflecting the gradual increase in academic attention to the field of family-friendly policies. In addition, this study uses an exponential function model to analyze the number of publications and citations in the field of family-friendly policies by year to understand its overall growth trend and development (Guan and Ma, 2007; Li et al., 2017). The R2 of the fitted curve for the number of papers published and the number of citations is equal to 0.8503 and 0.9408, respectively, indicating exponential growth in the number of studies in the field of family-friendly policies. This is due to the dramatic changes in employees’ work and family life as a result of the modern economy and changes in working attitudes, which have led to increasing attention and importance given to the area of family-friendly policies.

where C is the cumulative value of the number of publications (citations), X is the number of publications (citations) by year, y is the year, and α and β are parameters. The speed of family-friendly policy development is judged by the level of curve fitting.

Figure 4 shows a map of national (regional) collaborative networks for family-friendly policy research. The global distribution of research shows that countries (regions) are strengthening their scientific collaboration and that their R&D networks are becoming increasingly dense. Although researchers of family-friendly policies in various countries have certain cooperation and exchanges. However, there is still little cooperation between countries and the intensity of cooperation is not strong from a global perspective. High-yield countries are usually high-cooperation countries (Cobo et al., 2011). The exchanges and cooperation of researchers in various disciplines in different countries can promote the development of family-friendly policies in a multi-angle and in-depth direction. Therefore, countries should actively create opportunities for cooperation and exchange between different countries, thus promoting the development of family friendly policy research. The following conclusions can be drawn from the top 10 countries (regions) in terms of the number of publications (Table 2): (1) Researchers from the USA have the highest number of publications, far outstripping other countries with 288 publications. Meanwhile, the UK, China, and Australia actively promote research in this area with 62, 40, and 37 articles respectively. (2) Nodes with purple outer circles in CiteSpace have high intermediary centrality, which reflect the importance of the node (Chen, 2006). Therefore, the USA, UK, China, Australia and Spain have a greater scientific influence in this field. (3) Overall, research in this field is mainly dominated by countries from Europe and America. The nodes are dispersed and have relatively few links, indicating a lack of cross-country research and cooperation. Instead, collaboration mainly occurs among various institutions within each country. In addition, this study conducted keyword analysis on literature from the USA, UK, and China using CiteSpace, combined with their respective high-cited publications, to gain a specific insight into the main topics explored by the top-producing countries in the field. All three countries focused on “gender” and “conflict” (Voydanoff, 2004; Pedulla and Thébaud, 2015; Burnett et al., 2013; Lu et al., 2009), which also reflect the two main topics in this field of research: “how family-friendly policies affect work-family conflict” and “gender differences in family-friendly practices”. Furthermore, American researchers have focused on the impact of family-friendly policies on the well-being of both “women” and “children” groups (Budig and England, 2001; Hegewisch and Gornick, 2011), while researchers in the UK have focused on the “flexibility” of work arrangements in family-friendly policies (Kelliher and Anderson, 2010) and researchers in China have focused on the impact of family-friendly policies on employees’ “job satisfaction” (Qu and Zhao, 2012).

Institutions

The analysis of high-output scientific institutions in the field of family-friendly policies helps to understand and grasp cutting-edge developments as well as the authorities in the field. The highly productive institutions and their collaborations from 1985 to 2022 for family-friendly policies can be seen in Fig. 5. In terms of interinstitutional cooperation, institutions in the United States cooperate more extensively and with greater intensity than other countries (regions), but globally, there is less cooperation between institutions. Active communication and cooperation between institutions in different countries, regions, and disciplines promote family-friendly policy research in a multifaceted and in-depth direction; therefore, national family-friendly policy research institutions should strengthen cooperation and communication to promote the development of this field.

According to Table 3, the University of California is the institution with the highest number of publications on family-friendly policies, it conducts research on topics related to “The Impact of Family-Friendly Policies on Employee Work-Family Balance” (Alan et al., 2001; Guendelman et al., 2014) and “Gender Differences and Inequality in the Practice of Family-Friendly Policies” (Thebaud and Pedulla, 2016; Brady et al., 2020). And researchers at Texas University have focused more on the interaction between managers and family-friendly policies (Daverth et al., 2016; Bae and Skaggs, 2019). The top 10 institutions account for only 22.75% of the total literature output, indicating that family-friendly policy research is not concentrated in a few institutions. Geographically, nine of the top 10 research institutions in terms of the number of publications are located in the United States, indicating that high-level researches on family-friendly policies are concentrated there. Among the joint studies, two studies deserve special attention. Researchers from the University of California and University of Texas collaborated on a study of how unmarried men’s gender awareness and perceptions of family-friendly policies affect their preferences in future work-family life (Thebaud and Pedulla, 2016). This research has important implications for designing policies that promote gender equality in the workplace and at home. Another one was conducted by researchers at the University of Minnesota, Michigan State University and Portland State University. They reviewed more than 150 relevant studies to analyze whether family-friendly policies actually reduce work-family conflict and improve employee business outcomes (Kelly et al., 2008). This study responds to the ongoing controversy over the effectiveness of family-friendly policies, providing strong evidence for the implementation of family-friendly policies.

Authors

A collection of authors with a high number of publications and a high impact in a research field is a core group of authors (Wang, 2018). “Price law” (Price, 1963) is widely used in bibliometric analysis to find the core authors in a research area. According to its threshold screening principle, authors with “M” or more publications are considered core authors, and the calculation formula is as follows:

where Nmax is the number of papers by the author with the highest number of publications (Nmax = 6), M ≈ 2, so scholars with two or more publications are considered core authors in the field of family-friendly policy research. The total number of core authors in this research field is 114 (Table 4), and the number of core authors’ publications is 275, accounting for 46.61% of the total papers, which is less than the 50% target proposed by Price. This indicates that the core group of authors in the field of family-friendly policy research has not yet been fully formed and is still in the stage of ongoing development. Scholars in this field should strive to enhance cooperation and communication among themselves and produce more high-quality research results to promote the continuous development of this field. As seen from Table 4, the author with the highest number of articles is Blair-Loy, with six articles. The most frequently cited article by this author was published in 2002, which used a multilevel model to analyze the individual, organizational and social factors that influence the implementation of family-friendly policies (Blair-Loy and Wharton, 2002). As a representative comprehensive study of family-friendly policies, it has received widespread attention from scholars and has been cited 270 times.

Journals

It is necessary to focus on which journals the papers are published in when analyzing productivity. A total of 308 journals were covered in the data for this study. Table 5 shows the top 10 journals that are sources of literature in the field of family-friendly policy research from 1985 to 2022. According to Table 5, the total number of publications in the top 10 journals in this field was 120, accounting for 20.34% of the total literature. The Community Work Family is the most widely published journal, with 23 articles. The most cited paper in the journal is a review by Hegewisch and Gornick (2011) on the impact of family-friendly policies on women’s employment, with a total of 210 citations. The second most published journal is the International Journal of Human Resource Management, which also has the highest impact factor in the top ten. The study conducted by Fiksenbaum (2014) on the availability of family-friendly benefits received the most attention from scholars. This study found that a supportive work-family environment is crucial, and improving the availability of family-friendly benefits can promote a supportive work-family culture. Overall, with the exception of Community Work Family and Journal of Family Issues, these journals have impact factors greater than 2.0, indicating that there is significant interest in family-friendly policy research and that the main research areas of these journals are Business and Economics, Sociology, and Psychology.

Document co-citation analysis

Highly cited documents are very recognized references in a particular field of study. By analyzing the highly cited literature on family-friendly policies, it is possible to identify important documents and scholars in the field and then explore in depth the knowledge composition and theoretical foundations of family-friendly policies. As seen from Table 6, the top 10 most cited family-friendly policy references were all published 10 years ago (2011), suggesting that classical references are still the main source of existing knowledge streams on family-friendly policy. The most frequently cited family-friendly policy study by far is Budig and England (2001) published in the American Sociological Review, which has been cited 1003 times. The study examined the wage penalty for motherhood using a fixed-effects model and explored the reasons why women with children are paid less than other women, which has important implications for the study of discrimination in the female workplace. Notably, the article by Hammer et al. (2011) published in Journal of Applied Psychology is the latest of the 10 publications but has a high average annual citation rate of 26.62. This study discusses whether increasing supervisors’ use of family-supportive supervisory behaviors through training can mitigate work-family conflict, which provides an important basis for organizations to take work-family intervention measures from the level of supervisors.

“Co-citation” was first introduced by Henry Small (1973), an American information scientist, and refers to a co-citation relationship between two (or more) documents that are simultaneously cited by one or more later documents. Reference co-citation analysis reveals the structure and clustering relationships of citations, which in turn allows the core themes of the research area to be uncovered, enabling researchers to better understand the structure, relational networks, and evolution of knowledge in a given area (Chao and Jiancheng, 2017). Figure 6 shows the document co-citation network generated by CiteSpace. The time was set from 1985 to 2022, with a time slice of one year, while the software default G-index was used as the selection criterion, and the network was pruned using the pathfinder algorithm. Based on this, this study uses the default algorithm of CiteSpace, the log-likelihood rate (LLR), to perform a cluster analysis of the network to mine the target literature collection for research topics and other content. The left part of Fig. 6 shows the citation clustering view with an average silhouette value of 0.5968 > 0.5 and a modular value of 0.8237 > 0.3, indicating that the clusters in the map are independent and have a high degree of internal similarity, so the resulting clustering network has a significant structure and reasonable clustering results. The clustering results indicate that the knowledge found in the area of family-friendly policy consists of eight main directions (clusters). The cluster order is from 0 to 8, the smaller the number, the more research topics are included in the cluster. Each cluster is composed of multiple closely related research directions, and the distance between clusters indicates whether they are closely related. Clusters grouped together and overlapping represent that these research directions are closely related, and are often used to are studied together (cluster 2, 4, 5), while more independent clusters mean that research in this direction is usually done separately (cluster 6). Based on citation strength and intermediary centrality, we found the most important studies in major clusters:

The largest of all clusters is #0 (mother’s perception), containing 62 research topics. The main studies in this cluster are all around the impact of family-friendly policies on women, especially the differential impact on mothers who participate in the labor market. Among them, Korpi et al. (2013) focused on the differences in the perception and use of family-friendly policies by women of different social classes in the labor market. The study found that although the implementation of family-friendly policies has narrowed the gender gap in the labor market, it has helped women get more equal employment opportunities. But at the same time, it has exacerbated class inequality within the female group, especially the widening of the income gap has significantly increased. It reminds us that family-friendly policies should be viewed more comprehensively and carefully to ensure that they promote gender and class equality simultaneously. In addition, other important studies have shown that different types of family-friendly policies have different effects on mothers in the job market (Budig et al., 2016), and that social cultural attitudes play an important moderating role (Budig et al., 2012).

Cluster #1 (work-family support policies), contains 53 research topics. From the name of this cluster, it can be seen that the studies included in this cluster are targeted studies that are strongly related to family-friendly policies, and it also shows that support is an important meaning of family-friendly policies. In the cluster, the research of Allen (2001) is included in both the cluster and cluster #3, and is the most highly cited literature. It surveys the perceptions of people employed in a variety of occupations and organizations around the world about how their organizations support families. The degree that organizations support families is significantly related to the number of family-friendly policies the organization offers, the use of policies, and the support of supervisors. As a widely representative globalization study, it provides an important reference for the implementation of family-friendly policies in organizations, and its study model is also widely used in subsequent studies. Another important study is a comprehensive literature review (Eby, 2005) that emphasizes that creating a family-friendly employment environment requires both work (e.g., colleagues, managers, supportive policies) and family support, and it particularly affirms the importance of family-friendly policy in work-family research.

Cluster #2 (gender ideologies), contains 48 research topics. The studies in this direction focus on gender disparities associated with family-friendly policies, mainly due to the ideologies of the traditional division of labor (Kelly et al., 2008). The differences are mainly reflected in the fact that women tend to have more demands than men for family-friendly policies, whether formal or informal (Wharton et al., 2008), and that family-friendly policies have a greater impact on women’s work and family (Leslie et al., 2012). However, employees who use flexibility policies face stigmatization, as their use of such policies may be perceived by colleagues or superiors as a lack of effort at work (Munsch et al., 2014). As a result, many female employees opt out of using these much-needed policies in order to avoid prejudice that could affect their career advancement (Whittock et al., 2003). In order to reduce the negative impact of the use of family-friendly policies on female employees, Hook’s (2006) research points out that public family policies at the national level can lead to greater involvement of men in unpaid domestic work, thus creating an equal employment environment.

Cluster #3 (business outcome), contains 44 research topics. According to the name, we can know that the study of family-friendly policy is carried out from the perspective of organizational management, and its impact on the business outcome of employees is particularly concerned. These effects include both positive (e.g., increased organizational commitment, employee loyalty, and satisfaction) (Allen, 2001), and negative (e.g., detrimental to career development) (Thompson et al., 1999). Generally speaking, the higher the availability of family-friendly policies in an organization and the more employees use them, the more likely they are to have positive effects on both employees and the organization. In addition, the number of policies and employee characteristics (the percentage of female employees, the percentage of married employees, and the percentage of employees with the child or elderly care needs) moderates the impact of family-friendly policy availability and use on business outcomes.

Time-series analysis is an important element of data mining. By analyzing the burstiness of literature sequences, the timing of the burst of family-friendly policy research hotspots can be monitored, and the evolution of the research focus in the field is better depicted. Burst literature has received a significant increase in citations at a point in time or over a period, has received special attention from the academic field and is highly likely to have a significant impact on a research field (Chen et al., 2014). Therefore, based on the literature view in Fig. 6, this study used burst detection in CiteSpace to obtain the 10 most representative studies with the strongest bursts of citations (Table 7). There are two main topics covered by these literatures. One is a discussion on the impact mechanism of family-friendly policies in organizational management, that is, the relationship between organizational-level and employee-level factors and family-friendly policies (e.g., employee attitudes, organizational support, organizational commitment, turnover intention). The other is a discussion of the greater impact of family-friendly policies from a social perspective. The literature under this topic discusses the role of family-friendly policies in promoting individual work-life balance, the impact on the female and male labor market, respectively, and the gender equity and class equity issues related to family-friendly policies.

The first topic includes: Hochschild (1997) used a Fortune 500 company in the United States that implemented family-friendly policies as a case to explore how employees of the company dealt with the conflict between family life and work demands and found that although the organization implemented family-friendly policies, fewer employees used them. Thompson et al. (1999) developed a measure of family-friendly policies to conduct an empirical study on the relationship between family-friendly policy utilization, organizational loyalty, and work-family conflict, confirming that employees’ utilization of family-friendly policies and supportive work-family culture is positively related to organizational commitment and negatively related to work-family conflict and turnover intentions. A study conducted by Lambert (2000) verified a significant positive correlation between family-friendly policies, organizational citizenship behavior, and perceived organizational support. Allen (2001) collected data from employees employed in different organizations and occupations across the globe, and his findings suggest that the perception of the overall work environment determines employees’ responses to family-friendly policies. The abovementioned documents show that individual employees’ attitudes, perceptions, needs, and use of an organization’s family-friendly policies are important factors for the effective implementation of such policies. Therefore, organizations should fully consider employees’ needs and create a family-friendly workplace to actively promote employees using family-friendly policies.

The second topic includes: Eby et al. (2005) reviewed 190 work-family studies and summarized the main research topics in the field, including work-family conflict, work role stress, and work-family assistance, and suggested directions for future research. Frye and Breaugh (2004) tested and extended a model of the antecedents (family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work hours, assumption of childcare responsibilities) and consequences (job and family satisfaction) of two-way work-family conflict. Correll et al. (2007) confirmed the hypothesis that status discrimination plays an important role in the motherhood wage penalty, showing that firms tend to discriminate against mothers but not fathers. Hegewisch and Gornick (2011) reviewed family-friendly policies in OECD countries and analyzed the impact of different policies on the female labor market while highlighting that policy design has an equally important impact on male employees. Korpi et al. (2013) analyzed the impact of socioeconomic class and different types of family policies on gender inequality using 18 ECDO countries as examples. From the above studies, it is clear that gender and identity discrimination are common problems faced by women in the workplace; therefore, there is a need to focus on female employees in the design and implementation of family-friendly policies so that the well-being of female employees is ensured.

By sorting out the classic literature in this field, we obtain the following six theoretical foundations that existing family-friendly policy research mainly follows:

At the macro level, most of the existing family-friendly policy research has been conducted on rational choice theory and new institutionalism theory (Goodstein, 1994; Oliver, 1991). According to rational choice theory, companies, as profit maximizers in the market, will be motivated to provide benefits to their employees and take an active role in social responsibility when the benefits of providing family-friendly policies outweigh the costs required for the inputs (Carroll and Shabana, 2010). The new institutionalist theory further emphasizes the influence of social institutions on corporate family-friendly policies (Basu and Palazzo, 2009). On the one hand, companies are regulated and bound by legal systems to provide family-friendly policies to their employees to maintain their legitimacy. On the other hand, the concept of gender, organizational structure, and fertility policy will make the process and results of the implementation of family-friendly policies vary, and the impact on female employees is particularly significant (Bakker and Demerouti, 2007).

Family-friendly policy research from the medium view revolves around social exchange theory and social support theory. Under the social exchange theory perspective, organizations implement family-friendly policies to help employees alleviate work-family conflict, after which employees will reward the organization with positive work attitudes and high performance when they feel cared for by the organization (Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000). According to social support theory, social support includes supervisor support, colleague support, and family support (Kim et al., 1996). A range of formal and informal support from supervisors, colleagues, family members, and others can effectively improve work and family performance when individuals are under pressure from work-family conflict (Breaugh, 2004).

Family-friendly policy research at the micro level focuses on individual employees and is supported by role theory and resource conservation theory. Based on role theory, studies focus on the mitigating effect of family-friendly policy on negative effects, suggesting that individuals in society have multiple roles and that the accumulation of roles creates many different demands (Kahn et al., 1964), which can lead to role conflict and aggravate individual role stress if there are not enough resources to cope (Greenhaus and Beutell, 1985; Shaffer et al., 2001). Family-friendly policies provide resources to enable individuals to respond to these demands to prevent or reduce individual role stress (Ling and Powell, 2001). In terms of the direct positive effects of family-friendly policy, as work and family are the two main roles that individuals play in society, the two spheres inevitably interpenetrate each other, so organizations offering family-friendly policies to their employees enable them to better deal with the stresses that arise at work and thus bring positive emotions into their family life. At the same time, a happy family life will also bring benefits to employees at work. In addition, resource conservation theory suggests that when individuals are provided with certain resources, they are prone to acquire additional resources (Grandey and Cropanzano, 1999; Hobfoll, 2001). Therefore, family-friendly policies provide resources such as flexible working hours, leave, and grants that can be applied in the work and family spheres and that positively impact employees’ work and family life (Fu and Shaffer, 2001).

Keyword analysis

Keywords are extracted from the title or topic of a paper that accurately expresses the core content and essence of an academic paper. To fully demonstrate the research hotspots of family-friendly policies, this study used CiteSpace to analyze the keyword co-occurrence of family-friendly policy research and obtained the keyword co-occurrence network shown in Fig. 7. The larger the node labels, the more frequently the keyword appears, and based on the frequency of keyword occurrences, the research hotspots in the area of family-friendly policies can be identified. Table 8 lists the keywords that appear more than 25 times. High-frequency terms such as gender, conflict, women, impact, and work show the current hotspots of research on family-friendly policies, indicating that the outcome variables and antecedent variables of family-friendly policies have received significant attention from scholars. Specifically, gender is an essential control and antecedent variable, women are the main entry point, conflict is an important mediating variable, and exploring the impact of family-friendly policies on other variables is the focus of scholarly research. In terms of the centrality of keywords, gender, influence, and job satisfaction have the highest centrality, indicating that these three variables are most closely linked to other variables.

To further analyze the evolution of research hotspots in family-friendly policies, a TimeZone figure of the keywords was generated (see Fig. 8), which shows that scholars have focused on different research priorities in various periods. Table 9 presents all clusters and their representative terms, the largest of which is cluster #0 (supervisor support). According to the average year in which the clusters appear, the earliest occurrence is cluster #4 (organizational commit), in 2001, and the latest cluster is #6 (work-family balance), in 2015. In general, early family-friendly policies focused on issues such as gender differences in policy use and effectiveness, the impact of policies on organizational commitment, and childcare. In recent years, however, research has mostly focused on issues such as how family-friendly policies can contribute to work-family balance, flexibility policies, the impact of family-friendly policy on employee performance, and the advancement of mothers. Specifically, the evolution of family-friendly policy research can be divided into three main phases.

The initial stage of family-friendly policies (1970s–2000): Family-friendly policies that released the workforce and helped female employees to take on childcare responsibilities. The gradual decline in fertility rates in some developed countries during this period caused a shrinking workforce and an increasing number of women entering the labor market (Eby et al., 2005). In response to women’s desire to enter the labor market while still having to take on more family responsibilities due to the traditional division of gender roles, some companies successively provided family-related benefits to help ease work-family conflicts and motivate more women to enter the workplace (Kossek and Ozeki, 1998). As a result, family-friendly policies at this stage were mainly aimed at serving female employees, with common policies being maternity leave, part-time work, job sharing and a range of other services to help female employees with their childcare responsibilities (Lambert, 1993). In terms of overall usage, although organizations offer family-friendly policies, fewer employees use them (Hochschild, 1997). This is mainly because employees refuse to use family-friendly policies in order to avoid the possible negative effects of using them, which has led to discussions on the fairness of family-friendly policies, such as motherhood penalties (Budig and England, 2001).

The expansion of family-friendly policies (2000–2015): Family-friendly policies that highlight the welfare connotations and help workers to take on more family responsibilities. With the increasing number of dual-earner families, family affairs are gradually moving away from traditional gender roles (Hook, 2006). The reduction in the workforce due to accelerated global ageing has prompted organizations to offer more family-friendly policies to attract and retain employees (Carr et al., 2008), and policies that look after not only the needs of the employees themselves, but also their spouses, children, parents and other related relatives (Casper et al., 2007). Thus, the service coverage of family-friendly policies has been further expanded (Sangmook, 2008). The care of minor children was a key concern during this period, and in response, policies such as parental leave, child care allowances and work from home to meet child care needs were widely used (Guendelman et al., 2014).

The stage of steady development of family-friendly policies (2015–2022): Family-friendly policies that focus on fertility challenges and move towards full coverage. With the development of the modern economy and changes in people’s attitudes to work, which have led to dramatic changes in the content structure of work and family roles, family-friendly policies are receiving increasing attention and discussion. On the one hand, the growing problem of ageing is causing a further shortage of labor. At the same time, employees are increasingly calling for a work-family balance and are no longer seeking a single high income (Rashmi and Kataria, 2021). As a result, more and more organizations are also offering a diversity of benefits to their employees (Xiang et al., 2021). On the other hand, the issue of fertility has become a challenge affecting the balanced development of the global population in the twenty-first century. According to the report World Population Prospects 2022 published by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, fertility decline has become the general global trend today, with the sharpest decline in fertility levels in East Asia. In order to slow the decline in fertility and increase fertility intentions, many countries are focusing on family-friendly policies and emphasizing the creation of family-friendly workplaces. In this context, policies such as male paternity leave policies, flexible working policies and telecommuting have become hot topics of attention in recent years (Thebaud and Pedulla, 2016; Fuller and Hirsh, 2019; Walker and Gur, 2017).

A research frontier is a set of dynamic concepts and potential research questions that come to the fore. Research frontier terms are technical terms that appear with rapidly increasing frequency in a short period. Therefore, this study conducted keyword burst analysis based on keyword co-occurrence analysis to explore the frontiers of research in the field of family-friendly policies. Figure 9 shows the top 12 burst keywords detected by CiteSpace, from which it can be seen that the research frontiers in the field of family-friendly policies have been changing dynamically with the times, from women, gender, child care, welfare, and life between 2000 and 2010 to work, inequality, flexibility, time, and arrangements after 2011. The shift in research frontiers shows that in recent years researchers are trying to refine the exploration of family-friendly policies and are focusing on flexibility policies. On the one hand, due to the changes in work nature, much of it can be done online, which provides the necessary conditions for the use of flexibility policies (Kelliher and Anderson, 2010). On the other hand, as time conflicts are considered to be the most common work-family conflict (Houlfort et al., 2018), employees, whether married or not, seem to have high expectations and satisfaction with flexible working hours (Baltes Boris et al., 1999). It is also a family-friendly policy that is relatively inexpensive for organizations to use (Kumar et al., 2021).

Knowledge foundation

The main task of theoretical research is to answer the three most fundamental questions (2W1H): “what”, “why” and “how” (Whetten, 1989). Therefore, the 2W1H research framework of family-friendly policies based on the above analysis is summarized in Fig. 10.

The first question is what is a family-friendly policy? Only by clarifying the connotation of family-friendly policy and how it is measured can we conduct subsequent empirical studies with large samples and make more targeted policy recommendations, which is the purpose of conducting family-friendly policy research. Currently, there is a common consensus among researchers on the idea of a family-friendly policy as a collection of policies that help employees balance work and family life. However, due to differences in cultural backgrounds and realities, there are variations in the content of family-friendly policies practiced within countries, regions, and organizations, and therefore, there is not yet a consensus on the classification of what constitutes a family-friendly policy. The more representative classifications to date are as follows: dichotomies (John et al., 2009; Baltes Boris et al., 1999; Hammer et al., 2005), trichotomies (Glen, 1993), and quadratics (Kim and Wiggins, 2011; Lee and Hong, 2011). Hammer et al. (2005) classify family-friendly policies into two categories: work flexibility policies and kinship care policies. Glen (1993) explains that family-friendly policies take three forms: policies, benefits, and services. Policies are where an organization gives employees a great deal of flexibility; for example, permitting employees to not have a fixed work schedule and to organize their own work times. Benefits are generally about the organization providing employees with health insurance, paid holidays, paying for medical expenses, etc. Services include childcare centers, legal assistance, mental health counseling, etc., for employees in need. As research into family-friendly policies has increased, scholars have also refined them into four categories: flexible working arrangements (e.g., part-time work, telecommuting, no fixed commuting hours), family care (e.g., childcare, free health checks, childcare benefits), leave (e.g., maternity leave, sick leave, study leave) and assistance (e.g., care assistance, medical assistance, financial assistance). By integrating and understanding the connotations of existing family-friendly policies, this study clearly defines family-friendly policies as a collection of policies, programs, services and management measures in the workplace to help workers better fulfill their work-family responsibilities and balance their work-family life. The source of the policy is made up of three components. Firstly, the family-friendly policies to which workers are entitled under the law of each country (e.g., maternity leave). Secondly, family-friendly policies implemented by individual regions, trade unions and other sectors, which are usually only available to a specific range of workers. Thirdly, family-friendly policies designed and developed by the organization to which the employee belongs and available only to the organization’s employees (e.g., flexible working arrangements).

The second question is the “why” of family-friendly policies, including antecedents, mediators, and consequences. Only by identifying the impact of family-friendly policy and its internal mechanisms can we propose more targeted policy measures, which is the key element of family-friendly policy research. The antecedent variables of family-friendly policies involve three dimensions: individual employees, organizations, and society. In terms of the individual employee dimension, researchers have mostly focused on how individual employee characteristics, attitudes, and perceptions in organizations affect the effectiveness of policy implementation. In short, researchers generally agree that for family-friendly policies to be effective in an organization, both the organization and the employee need to be involved collaboratively. Similarly, the impact of family-friendly policies is inseparable from the employees and the organization. For individual employees, numerous empirical studies have shown that family-friendly policies are positively correlated with work attitudes, engagement, and creativity but negatively correlated with work stress, turnover intentions, and counterproductive behavior, especially for women (Lee and Hong, 2011; Kossek and Ozeki, 1998). In terms of the organizational dimension, researchers have mostly looked at the culture, attributes, size, and other characteristics of organizations to analyze which organizations are more willing to offer family-friendly policies to their employees. The impact on the organization level is that family-friendly policies can help retain talent and effectively improve organizational performance (Gray and Tudball, 2003; Perry-Smith and Blum, 2000). In terms of the social dimension, studies have found that, in addition to trade unions and legal norms that make it mandatory for organizations to provide family-friendly policies, the degree of gender equality in a society and government incentives and support measures can prompt organizations to take the initiative to provide family-friendly policies to their employees. For society, more effective family-friendly policies offered by organizations and the increased use of family-friendly policies by employees have a positive impact on improving the employment environment of women (Xiang et al., 2021; Fuller and Hirsh, 2019), increasing fertility intentions and contributing to better family parenting functions. The above impacts are mainly achieved through mediating mechanisms such as reducing employees’ working hours, increasing supervisory support, and mitigating work-family conflicts.

Finally, there is the question of “How”, i.e., how to effectively implement family-friendly policies. Three basic elements are essential for an organization to be able to effectively implement family-friendly policies: first, the organization must set up a standardized system related to family-friendly policies and give formal support to the implementation of family-friendly policies at the institutional level; second, managers should actively create a family-friendly culture in the organization and create a supportive work environment for employees; and third, organizations may have problems such as differential treatment, nonapplicability to employees and unintended losses in the process of implementing family-friendly policies and need to take appropriate safeguards in advance to deal with these potential problems. Organizations generally follow four steps to implement family-friendly policies (Poelmans Steven, 2005:

-

(1)

The organization decides whether to offer family-friendly policy based on its circumstances;

-

(2)

Dedicated staff and departments design the content of family-friendly policy to suit the organization to improve the policy fit;

-

(3)

Appropriate supporting safeguards are put in place to leverage the positive effects of family-friendly policy;

-

(4)

The organization decides when the family-friendly policy will be implemented, how it will be implemented, and which employees can use it.

In addition, this paper argues that after an organization has implemented family-friendly policy, two steps should be taken:

-

(5)

Assess the effectiveness of the implementation (e.g., whether it has had a positive effect on the organization and met the needs of the employees);

-

(6)

Provide timely feedback on issues arising from the implementation of the family-friendly policy and address them so that family-friendly policy implementation creates a virtuous cycle and continues to have positive effects.

Conclusion

The preceding bibliometric analysis leads to the following conclusions:

-

(1)

The overall analysis of the research literature on family-friendly policies shows an exponential increase in both the number of studies and the number of citations. In particular, in recent years, family-friendly policies have received widespread attention and discussion for various reasons, such as the increasing number of female employees entering the workplace, the increase in dual-earner families, and the change in people’s perception of work and life. The field of family-friendly policies is now growing steadily and we predict this will continue.

-

(2)

From the journals published and the fields involved with family-friendly policy research, it can be seen that family-friendly policy research is interdisciplinary and involves many fields, including economics, management, sociology, and psychology. Most of the existing studies on family-friendly policies have been conducted at the level of enterprises or organizations to explore issues related to human resource management. As the research on family-friendly policies gradually expands from the “internal management field of organizations” to the “interaction between organizations and society”, some scholars have started to explore family-friendly policies from a social perspective (Berg et al., 2013; Lambert, 1993). Future research should focus more on the social implications of family-friendly policies and actively explore issues such as social welfare levels, fertility intentions, and family performance. With the continuous development of social and economic development and technological progress, the boundaries between various disciplines are gradually narrowing. Thus, family-friendly policy research across fields and disciplines will become a future research trend.

-

(3)

In terms of core authorship and cooperation with research institutions, high-level research institutions in the field of family-friendly policy research are mainly concentrated in Western countries such as the US and the UK, and a core group of authors has not yet been formed. With the well-being of employees becomes increasingly important, more research on family-friendly policies needs to be systematically conducted. In particular, the practice of family-friendly policies varies from country to country, and international exchange and cooperation can help countries learn from each other’s good experiences and promote the globalization process of family-friendly policy development.

-

(4)

According to the document co-citation analysis, the core research object of family-friendly policy research is women, especially the mother group, and the core topics mainly include whether family-friendly policies exacerbate gender discrimination in the workplace, the unfair treatment of mothers after using family-friendly policies, the relationship between family-friendly policies and work-family conflicts, and employees’ attitudes toward family-friendly policies. In terms of theory, existing research is mainly based on conservation of resources theory, social support theory and social exchange theory. Family-friendly policies based on these three theories are respectively regarded as a kind of resource, support or welfare for workers. Future research should seek new theory perspectives to enrich the theory basis of family-friendly policy research. At the same time, future research should integrate multiple theories into the study in order to clarify the action mechanisms and boundary conditions of family-friendly policies from multiple perspectives.

-

(5)

In terms of keyword co-occurrence and emergent words, on the one hand, gender, influence, and job satisfaction are high-frequency keywords that have been the hotspots of research on family-friendly policies for more than 30 years. On the other hand, policy fairness, flexibility policies, and family-friendly policies regarding scheduling have been at the forefront of research in recent years. This leads us to predict that the main directions of future research will include the issue of fairness in family-friendly policies, the more diverse impacts of family-friendly policies and employees’ perceptions of family-friendly policies, with flexibility in relation to working arrangements being the type of policy that will be focused on. Furthermore, family-friendly policies have been studied for married employees (Lu et al., 2009), especially female employees. Although research has begun to focus on men in recent years (Suzanne and Melissa, 2010; Fernández-Cornejo et al., 2020), there is still a need to further explore the mechanisms by which family-friendly policies work for groups such as male employees, single employees, and those without a caregiving burden. Future research should expand the scope of the study to explore the well-being of different types of employees.

Through the above analysis, we have summarized the knowledge foundation of family-friendly policies (the 2W1H research framework). This includes the definition and classification of family-friendly policies (dichotomous, trichotomous and quadratic). At the same time, this study also sorts out the dynamics driving family-friendly policies and the effects produced by family-friendly policies (the antecedent and outcome variables). Multiple forces, both internal and external to the organization, can be the driving force behind the practice and development of family-friendly policies, including the three dimensions of individual employees, the organization and society (e.g., employee needs, organizational culture, social support, etc). Therefore, the effective implementation of family-friendly policies in organizations requires the participation of multiple social forces. The positive effects of family-friendly policies are mainly reflected in the benefits to employees’ physical and mental health, work attitudes and behavior, which in turn bring direct or indirect benefits to the organization and contribute to its long-term development. Meanwhile, at the social level, it contributes to an increase in fertility rates and promotes the building of a family-friendly society. The problems with family-friendly policies, on the other hand, are mainly the inequity in the use of the policies by employees and the potential penalties in terms of wages or career progression for employees after the use of the policies, which has led to the existence of countries where employees have had to reduce or abandon the use of family-friendly policies for fear or avoidance of the negative consequences of using them.

To better carry out research and practice on family-friendly policies so that they have positive effects on employees, organizations, and society. As the first study using scientometric method to systematically analyze family-friendly policy research, it helps researchers to better clarify family-friendly policies and identify the gaps in current studies and practice. Specifically, This study provides researchers of family-friendly policies with valuable information to help them better identify potential collaborators, current hotspots and future research directions. It also provides practical guidance for managers in using family-friendly policies to help organizations implement family-friendly policies more scientifically, enhance the effectiveness of family-friendly policies, and avoid potential negative impacts in practice. As for policymakers, they can identify the shortcomings of current family-friendly policies and problems in practice from this study, to determine the landing points and directions for future policy formulation. However, there are some limitations to this study. Although the WoS database contains relatively comprehensive documents on family-friendly policy research, it is still possible that some documents were missed. In addition, limitations in software, language, access rights, etc. forced us to exclude some document types. Future studies could include more literature and consider the use of multiple bibliometric tools.

Data availability

The dataset used in this study can be reproduced by following the method described. The dataset and associated files can be made available upon reasonable requests with permission of Clarivate Analytics.

References

Alan LS, Yuan-Ting, Saltzstein GH (2001) Work-family balance and job satisfaction: the impact of family-friendly policies on attitudes of federal government employees. Public Adm Rev 61(4):452–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00049

Alexandre R, Isabelle W, Michel K (2016) Is SAM still alive? A bibliometric and interpretive mapping of the strategic alignment research field. J Strateg Inform Syst 25(2):75–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2016.01.002

Allen TD (2001) Family-supportive work environments: the role of organizational perceptions. J Vocat Behav 58(3):414–435. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2000.1774

Aryee S (1992) Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict among married professional women: evidence from singapore. Hum Relat 45(8):813–837. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679204500804

Bae KB, Skaggs S (2019) The impact of gender diversity on performance: The moderating role of industry, alliance network, and family-friendly policies–Evidence from Korea. J Manage Organ 25(6):896–913. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2017.45

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The job demands-resources model: State of the art. J Manage Psychol 22(3):309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115

Baltes Boris B, Briggs TE, Huff JW, Wright JA, Neuman GA (1999) Flexible and compressed workweek schedules: a meta-analysis of their effects on work-related criteria. J Appl Psychol 84(4):496–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.4.496

Bao X, Ping K, Jie W, Liang P (2021) Material penalty or psychological penalty? The motherhood penalty in academic libraries in China. J Acad Librarianship, 47(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACALIB.2021.102452

Basu K, Palazzo G (2009) Corporate social responsibility: a process model of sensemaking. Acad Manage Rev 33(1):122–136. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2008.27745504

Berg P, Kossek EE, Baird M, Block RN (2013) Collective bargaining and public policy: pathways to work-family policy adoption in australia and the united states. Euro Manage J 31(5):495–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.04.008

Blair-Loy M, Wharton AS (2002) Employee’s use of work-family policies and the workplace social context. Social Force 80(3):813–845. https://doi.org/10.2307/3086458

Brady D, Blome A, Kmec A (2020) Work-family reconciliation policies and women’s and mothers’ labor market outcomes in rich democracies. Socio-Econ Rev 18(1):125–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwy045

Breaugh F (2004) Family-friendly policies, supervisor support, work–family conflict, family–work conflict, and satisfaction: a test of a conceptual model. J Bus Psychol 19(2):197–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-004-0548-4

Budig MJ, England P (2001) The wage penalty for motherhood. Am Sociol Rev 66(2):204–225. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657415

Budig MJ, Misra J, Boeckmann I (2012) The motherhood penalty in cross-national perspective: the importance of work-family policies and cultural attitudes. Oxford Univ Press 19(2):163–193. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs006

Budig MJ, Misra J, Boeckmann I (2016) Work-family policy trade-offs for mothers? unpacking the cross-national variation in motherhood earnings penalties. Work Occup 43(2):119–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888415615385

Burnett SB, Gatrell CJ, Cooper CL, Sparrow P (2013) Fathers at work: a ghost in the organizational machine. Gender Work Organ 20(6):632–646

Butts MM, Casper WJ, Yang TS (2013) How important are work-family support policies? a meta-analytic investigation of their effects on employee outcomes. J Appl Psychol 98(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030389

Carr JC, Boyar SL, Gregory BT (2008) The moderating effect of work-family centrality on work-family conflict, organizational attitudes, and turnover behavior. J Manage 34(2):244–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307309262

Carroll AB, Shabana KM (2010) The business case for corporate social responsibility: a review of concepts, research and practice. Int J Manage Rev 12(1):85–105. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00275.x

Casper WJ, Weltman D, Kwesiga E (2007) Beyond family-friendly: the construct and measurement of singles-friendly work culture. J Vocat Behav 70(3):478–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.01.001

Cassar V, Bezzina F, Fabri S, Buttigieg SC (2020) Work stress in the 21st century: a bibliometric scan of the first 2 decades of research in this millennium. Psychol-Manage J 23(2):47–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/mgr0000103

Castles FG (2003) The world turned upside down: below replacement fertility, changing preferences and family-friendly public policy in 21 OECD countries. J Eur Soc Policy 13(3):209–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/09589287030133001

Chao Z, Jiancheng G (2017) How to identify metaknowledge trends and features in a certain research field? evidences from innovation and entrepreneurial ecosystem. Scientometrics 113(2):1177–1197. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2503-y

Chen C (2006) Citespace II: detecting and visualizing emerging trends and transient patterns in scientific literature. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 57(3):359–377. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20317

Chen C, Dubin R, Kim MC (2014) Orphan drugs and rare diseases: a scientometric review (2000-2014). Expt Opin Orphan Drugs 2(7):709–724. https://doi.org/10.1517/21678707.2014.920251

Chen C, Zhigang H, Shengbo L, Hung TS (2012) Emerging trends in regenerative medicine: a scientometric analysis in CiteSpace. Exp Opin Biol Ther 12(5):593–608. https://doi.org/10.1517/14712598.2012.674507

Cobo MJ, López-Herrera AG, Herrera-Viedma E et al. (2011) Science mapping software tools: Review, analysis, and cooperative study among tools. J Am Soc Inform Sci Technol 62(7):1382–1402. https://doi.org/10.1002/ASI.21525

Correll SJ, Benard S, Paik I (2007) Getting a job: Is there a motherhood penalty. Am J Sociol 112(5):1297–1338. https://doi.org/10.1086/511799

Cowgill K, Taylor TH, Schuchat A, Schrag S (2003) Report from the cdc. awareness of perinatal group b streptococcal infection among women of childbearing age in the united states, 1999 and 2002. J Womens Health 12(6):527–32. https://doi.org/10.1089/154099903768248221

Daverth G, Cassell C, Hyde P (2016) The subjectivity of fairness: managerial discretion and work-life balance. Gender Work Organ 23(2):89–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12113

Donthu N, Kumar S, Mukherjee D, Pandey N, Lim WM (2021) How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: an overview and guidelines. J Bus Res 133:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070

Eby LT, Casper WJ, Chris B, Andi B (2005) Work and family research in IO/OB: content analysis and review of the literature (1980–2002). J Vocat Behav 66(1):124–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003

Fernández-Cornejo JA, Pozo-García ED, Escot L, Belope-Nguema S (2020) Why do spanish fathers still make little use of the family-friendly measures? Soc Sci Inform 59(2):355–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018420927153

Fiksenbaum LM (2014) Supportive work–family environments: implications for work–family conflict and well-being. Int J Hum Resour Manage 25(5):653–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.796314

Frone MR (2000) Work-family conflict and employee psychiatric disorders: the national comorbidity survey. J Appl Psychol 85(6):888–895. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.6.888

Fu CK, Shaffer MA (2001) The tug of work and family: direct and indirect domain-specific determinants of work-family conflict. Personnel Rev 30(5):502–522. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005936

Fuller S, Hirsh CE (2019) “Family-friendly” jobs and motherhood pay penalties: the impact of flexible work arrangements across the educational spectrum. Work Occup 46(1):3–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888418771116

Glass JL, Estes SB (1997) The family responsive workplace. Ann Rev Sociol 23(1):289–313. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.23.1.289

Glen G (1993) Balancing Work and Caregiving for Children, Adults and Elders. Ageing Soc 13(4):708–710. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00001550

Goodstein JD (1994) Institutional pressures and strategic responsiveness: Employer involvement in work-family issues. Acad Manage J 37(2):350–382. https://doi.org/10.2307/256833

Grandey AA, Cropanzano R (1999) The conservation of resources model applied to work-family conflict and strain. J Vocat Behav 54(2):350–370. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1666

Gray M, Tudball J (2003) Family-friendly work practices: differences within and between workplaces. J Ind Relat 45(3):269–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/1472-9296.00084

Greenhaus JH, Beutell NJ (1985) Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Acad Manage Rev, 10(1):76–88. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1985.4277352

Guan JC, Ma N (2007) China’s emerging presence in nanoscience and nanotechnology. Res Policy 36(6):880–886. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.02.004

Guendelman S, Goodman J, Martin K et al. (2014) Work-family balance after childbirth: the association between employer-offered leave characteristics and maternity leave duration. Matern Child Health J 18(1):200–208. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1255-4

Hammer LB, Neal MB, Newsom JT, Brockwood KJ, Colton CL (2005) A longitudinal study of the effects of dual-earner couples’ utilization of family-friendly workplace supports on work and family outcomes. J Appl Psychol 90(4):799–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.4.799

Hammer LB, Kossek EE, Anger WK, Bodner T, Zimmerman KL (2011) Clarifying work-family intervention processes: the roles of work-family conflict and family-supportive supervisor behaviors. J Appl Psychol 96(1):134. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020927

Harrison CR, Phimphasone-Brady P, Diorio B, Raghuanath SG, Sauder KA (2020) Barriers and facilitators of national diabetes prevention program engagement among women of childbearing age: a qualitative study. Diabetes Educ 46(3):279–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721720920252

Hegewisch A, Gornick JC (2011) The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: a review of research from OECD countries. Community Work Family 14(2):119–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2011.571395

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested‐self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–421. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00062

Hochschild AR (1997) When work becomes home and home becomes work. Calif Manage Rev 39(4):79–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/41165911

Hook JL (2006) Care in context: Men’s unpaid work in 20 countries, 1965-2003. Am Sociol Rev 71(4):639–660. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100406

Houlfort N, Philippe FL, Bourdeau S, Leduc C (2018) A comprehensive understanding of the relationships between passion for work and work-family conflict and the consequences for psychological distress. Int J Stress Manage 25(4):313. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000068

ISI (2000) Web of Science Core Collection. https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science-core-collection/. Accessed 29 Sept 2022