Abstract

Spatial enquiry in literature has opened new doors for understanding the relationship between physical and mental space. This paper analyses how an individual’s sense of space can influence their understanding of themselves and others. This study identifies the similarities between Ray Oldenburg’s concept of place and Edward Soja’s concept of space. Moreover, it integrates both theories by locating Oldenburg’s triad of place (home, workplace, and third place) as a part of Soja’s concept of real space (firstspace). The lack of discernibility between home and workspace exerts itself in protagonist Stevens’ obsession with his profession. This paper also examines how disorientation in the trifold conception of place causes Stevens to be an emotionally and spatially repressed character. The study elaborates on the role of third place and thirdspace. It also analyses Steven’s six-day journey into the countryside as an introspective journey into his past. This study aims to find how social interactions in the third place have helped Stevens unlearn and relearn hegemonically influenced ideologies on duty and dignity. Further, it helps Stevens resolve his denial and repression, properly channelling the flow of spatial energy. This study also identifies thirdspace as a transformative space that helps Stevens find closure and accept his regretful past.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Kazuo Ishiguro, as a Japanese-British writer, has created his own literary world in which his memories of Japan and his experiences in England are intertwined. The most intriguing quality of his novels is their ability to bring out ‘great emotional force’ through characters struggling with their own emotions. His novels deal with not only the bitter past of the protagonists but also their efforts to come to terms with their memory. The Remains of the Day is in the first-person point of view of Mr. Stevens, who works at Darlington Hall as a butler. He narrates his past while taking a six-day trip to the countryside, as suggested by his new employer, Mr. Farraday. Stevens idolises his old employer, Lord Darlington, and is always seen “standing in the shadows” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 75) of Lord Darlington, both literally and metaphorically. Devoted to Lord Darlington and the conventional practices of England, Stevens finds it challenging to adapt to the ways of his new American employer. While looking back at his life, he regrets the decisions influenced by the blind trust he had in Lord Darlington. His journey drives him to take responsibility for his actions and helps him accept himself as he tries to confront life with new perceptions.

Memory consists of experiences about people and their actions anchored in spatial and temporal contexts, so the relationship between emotions and places is very apparent. On the surface level, Ishiguro’s novels seem like a story about protagonists dealing with their past resentments by delving into their memories, but a deeper reading of the novel suggests the active role of places in the characters’ memories. His protagonists use their profession as an escape from their painful reality. The Darlington Hall in The Remains of the Day, Ono’s house (which he bought from the prestigious Sugimura family) in An Artist of the Floating World, and Hailsham School in Never Let Me Go are places that have a prominent bond with the protagonists. The protagonists associate their identity with these places, letting them be stuck inside that space and anchored to it wherever they go. The author has also synchronised the physical condition of these places with the protagonists’ mental state. In “Artist of the Floating World,” for example, the reconstruction of Ono’s house following war damage is strategically coordinated with Ono’s reconstruction of his flawed ideologies. For Kathy, Hailsham remains an impinging yet the only safe space, holding beautiful memories and terrifying trauma. In The Remains of the Day, Stevens has accustomed himself to Darlington Hall to such an extent that he cannot distance himself from the hold of the space, depriving himself of any human connection beyond Darlington Hall. When Miss Kenton brings flowers to brighten Stevens’ room, he refuses to have them in his room, saying, “The butler’s pantry… is a crucial office, the heart of the house’s operations” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 173). His unwillingness to accept changes in his space and his compulsive behaviour to obey orders demonstrate that he lacks the freedom to act independently. Stevens acts not from his mind but from “what was required” (Ishiguro, 1989, p.16) of him from his employers. In another instance, he claims that even though he “did not see a great deal of the country in the sense of touring the countryside and visiting picturesque sites, did actually “see” more of England than most, placed as we were in houses where the greatest ladies and gentlemen of the land gathered.” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 4) These instances point to Stevens being spatially repressed and deceiving himself that he is happy within the walls of Darlington Hall.

In his book, The Oxford English Literary History: Volume 12: The Last of England?, Randall Stevenson observed that in the latter part of the twentieth century, “geography and space often seemed fractured and disoriented” (Stevenson, 2005). Although the term ‘disorientation’ has a negative connotation, this disorientation of space has led to spatial studies looking at “space” as an “analytical concept” (Soja Edward, 2009) rather than just a physical entity. The disorientation of spaces in literary texts and their analysis provides an all-encompassing view, including psychological and sociological interpretations of the text. Soja Edward (2008) sums up the inevitability of spatiality in analysing a literary text that “space comes first, before seeing things historically or socially.” As space is the quintessence of existence, analysing a text using various spatial theories can address various gaps related to psychology and social behaviour.

Henri Lefebvre’s The Production of Space, a Marxist critique, is a seminal text in which he proposed the trifold concept of space, “The perceived-conceived-lived triad (in spatial terms: spatial practice, representations of space, representational spaces)” (Lefebvre Henri, 1991). This triad of space laid the foundation for other theorists, such as Bhabha (1994) and Edward Soja, who firmly believed that space is an influential element in a narrative. Edward Soja draws on the trifold conception of space, which he calls “real, imagined and lived” spaces (Soja Edward, 2009). The terms space and place are ambiguously used in interchangeable contexts, but according to Soja, space is the consolidation of “place, location, landscape, architecture, environment, home, city, region, territory, and geography” (Soja Edward, 2009). Therefore, it is evident that place is an integral component of space. Space is generally seen as an abstract entity, whereas place is seen as a physical entity. Space takes into account both sociocultural and psychological aspects, whereas place is an observable dimension. Accordingly, space exerts itself in a state of fluidity, which permeates various fields of knowledge such as cultural studies, linguistics, and narratology. Thus, the fluidity of the term and the concept enables various sociospatial critiques. After the spatial turn, critical literary discourses on spatiality have risen to prominence, yet it is a potentially less explored subject. The need to anchor this study on integrating two spatial theories arises from addressing the role of social spaces in shaping/conditioning the protagonist’s psyche. As Lefebvre has noted, space is inherently social, and the influence of places, such as home or workplace, on the mental space of the protagonist is inevitable.

A review of available literature on Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day shows that significant attention has been given to Ishiguro’s use of memory as a narrative technique and the psycho-analytical character study of Stevens (Calinescu, 2020; Furst, 2007; De Chavez, 2021; Duangfai, 2018; Leeb Claudia (2021); Khalaf, 2017; Lang, 2000; Nakajima, 2018; Webster Thomas, 2013; Wall, 1994; Wang, 2020; Yi, 2016). As far as the novel The Remains of the Day is concerned, the research gap arises from the unexplored question of how Stevens resolves emotional and ideological repression at the novel’s end. Stevens’ obsession with his profession is the reason behind his repression and inability to build a meaningful connection with his family and colleagues. However, the reason behind his workaholism, the underlying issue for his denial and repression, needs to be explored more. Throughout the novel, Stevens is seen engrossed in the space of Darlington Hall, and there seems to be no memory that does not involve Darlington Hall. Stevens has conditioned himself to detach his feelings because he has always changed himself according to the requirements of the space. Not only does the space encroach on Stevens to repress his emotions, but it also limits his spatial perception. Adapting a spatial enquiry to Stevens’ six-day vacation to the countryside using the proposed integrated theory helps investigate how he finds closure by interacting with strangers and accepting his regretful past.

Locating Oldenburg’s concept of place in Soja’s concept of space

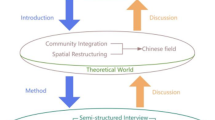

Place is an integral part of space because space is nothing but the abstract idea, imagination, or perception of a place. Therefore, without a place, such abstraction is not possible. In his book The Great Good Place, Ray Oldenburg proposes the trifold conception of place. According to him, the first place is one’s home; the second place is the workplace; and the third place is a common place where random people meet (café, beach, etc.). On the other hand, Edward Soja talks about the trifold conception of space—real, imagined, and lived spaces. The firstspace or the real space is the actual physical place or environment; the secondspace, or the imagined space, is the conceptual space based on the real space; and the thirdspace, or the lived space is a combination of both real and imagined space. While looking closely at these theories, they intersect at one point.

The real space that Soja is talking about is the same as Oldenburg’s trifold concept of place. Figure 1 shows Oldenburg’s triad can be located inside Soja’s real space. This integrated approach is important because the three places suggested by Oldenburg have proven to be an important part of human beings’ psychological development. These places help people to understand themselves better by understanding their physical environment. This understanding helps them develop their social self and establish human connections. This integrated approach is needed because places influence the “coexistence and development” (Meskell Brocken, 2020) of the other spaces. The impact of each place on one’s psychological development is inevitable. Furthermore, Fig. 1 shows how the spaces are interconnected and the interconnection of places within the firstspace (real space). Therefore, the interdependency of one with the other is very comprehensible. To foster healthy psycho-social development, it is crucial to have a comprehensive understanding and personal experience of various places, as this can significantly impact one’s mental spaces.

The protagonist of this novel, Stevens, experiences disorientation in his experience of the firstspace (real space). Real space comprises the trifold places—home, work, and third place. Stevens lives and works at his master’s place, so there is an absence of first place—home. He has no other place to go after his work except for his pantry (located inside Darlington Hall). Therefore, his experiences and interactions are limited to his workplace. Even in his workplace, he does not have the liberty to act on his own, and rather, he must perform only what is “within (his) realm” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 209) as a butler. He convinces himself that fulfilling Lord Darlington’s command is the only purpose of his life. Despite the potential cost of losing significant people in his life, he makes great sacrifices to satisfy his employer. However, since he has no personal space to call his own, it leaves a void in his firstspace (real space). As there is disorientation in this triad of places, Stevens cannot explore the third place, which further creates disorientation in the triad of spaces. When he begins his trip to the countryside, he admits that “for the first time in many a year, I’m able to take my time” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 71). Stevens, as a spatially repressed person, had limited access to the outside world, and he “never think(s) to look at it for what it is” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 234); rather, he tries to find a place in the world of his employer.

Third Place and Thirdspace

Ray Oldenburg (1999) defines Third Place as “A place that is a leveler, by its nature, an inclusive place. It is accessible to the general public and does not set formal criteria of membership and exclusion.” He identifies the “three realms of human experience,” where the first place is “domestic”; the second place is “productive”; and the third place acts as a balance between the realms of home and work (Oldenburg, 1999). Third place, as a centre of socialisation, and “anchor of community life” (Myers, 2012) provides relief from the stress and monotony of life. They also act as a remedial place, where “a transformation must occur as one passes through the portals of a third place.” (Oldenburg, 1999). As the third place is a leveler, hierarchy or domination cannot exist within the Third place.

The trifold conception of space presupposes the reciprocity and overlapping coordination of spaces in human experiences. In cultural studies, the term thirdspace denotes a hybrid identity arising from the clash of different cultures. For instance, Kazuo Ishiguro is called an “unusual immigrant” by Randal Stevenson (2005) because, for Ishiguro, the idea of home is complex. Despite spending most of his life in England, he has strong ties to his native Japan. He says that he had created an “imaginary homeland” (Ishiguro and Kenzaburo, 1991) in his mind because he did not know what Japan looked like (Ishiguro, 2008). Ishiguro’s works reflect his hybrid identity by portraying protagonists who experience homelessness. Oldenburg talks about the physical environment of the third place and its importance in a person’s social life, whereas Soja talks about thirdspace as an ideological and psychological space that can “transcend stubborn binaries” (Soja Edward, 1996). This study places third place inside the sphere of real space (firstspace). Although the ‘places’ are an integral part of the firstspace, owing to their interdependency, they also exert influence on other spaces. All the spheres in Fig. 1 constitute an interconnected flow of energy. If the flow is disrupted, it corrupts the spatial experience of a person. In this novel, there is a disruption in Stevens’ flow of energy because of the void created in his firstspace (real space) due to the absence of a home (first place). Therefore, Stevens becomes a spatially repressed character who goes nowhere beyond the walls of Darlington Hall. David James has noted that “conflicts and instabilities also reveal Stevens’ underlying vulnerability. His reluctance to abandon discursive properties, even deliberately in the case of convivial banter, is altogether ingrained—integrally part of his physiological make-up.” (James, 2009). However, when he decides to go on a six-day trip to the countryside, he obtains a better understanding of the quality of his spaces.

Through the character of Stevens, this study assesses how his interactions in the third place change his overall understanding of his firstspace, thereby resolving his internal conflict. As his disruption in the firstspace is resolved, the energy flow continues to the spheres of the second and third spaces. The protagonist struggles with emotional repression and denial throughout his life, but taking on this journey helps him to unlearn a few of his misguided ideologies. These ideologies are often hegemonically ingrained into his mind, but through the interactions in the third place, he unlearns and relearns those ideologies. As Shaffer observes, “Stevens engaging in the act of breaking out of the space, both material and psychological, is an act of rebellion against a life of subservience and numb routine; a final, desperate attempt at understanding and redefining his self and his world” (Shaffer Brian, 1998). In the last chapter of this novel, Stevens, for the first time, opens up to a stranger at the pier. The pier is where a random crowd meets and shares the beauty of the evening and the lights. This venting out of emotion indicates his acceptance of his past. Stevens’ understanding of his workplace and his hegemonically influenced ideas changes with the interactions in the third place, thus creating an enhanced insight in his imagined space (secondspace). As thirdspace connects both first and second spaces, Stevens gets to indulge in the introspection of the memories and come to terms with his denial and repression. Although interactions in the third place help him resolve the conflict, the mental space (thirdspace) helps him accept his past mistakes. The latter part of the article explains how thirdspace acts as a tool to achieve closure.

Duty, dignity, and denial

The Remains of the Day “is a story primarily about regret: throughout his life, Stevens puts his absolute trust and devotion in a man who makes drastic mistakes.” (Ekelund, 2005) His misguided devotion towards his master, Lord Darlington, stems from his admiration for his father’s professionalism. Stevens, in his past, used to be a person who basked comfortably in his flawed perception of dignity and believed that his father was “the embodiment of dignity” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 35). On the first day of his six-day trip to the countryside, he deliberates on the greatness of the English landscape and proclaims, “the landscape of our country (Great Britain) alone would justify the use of this lofty adjective.” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 29), which leads him to ponder the question, “What is a great Butler?” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 29). By using ‘what’ instead of ‘who,’ it is evident that Stevens has reduced the greatness of a Butler merely to the extrinsically observable ‘things’ rather than the internal qualities. From the beginning of the novel, Stevens tries to fit himself into the requirement of the Hayes Society, which proposes that a butler who has “dignity in keeping with his position” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 33) can only be admitted into their prestigious society and that the “applicant be attached to a distinguished household.” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 119) The novel opens in 1956; Stevens tries to fit himself into this two-line definition of the Hayes Society. However, the irony lies in the fact that the Hayes Society was forced to be closed in 1932 or 1933. For Stevens, the Hayes Society is a symbol of prestige and power, so defining himself according to its criteria gives him solid proof that he is also a great butler.

Stevens alludes to two different incidents from his father’s career, in which he believes the greatness of his father as a Butler is very evident—when his father was forced to serve a general who killed one of his sons and when his father expressed his anger when his employer was being abused. He says his father has a “special quality” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 41) but does not readily explain it. But later, Stevens is seen showing high regard for how well his “father hide(s) his feelings” and proclaims his father to be a “personification” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 43) of dignity. His father sacrificing his personal space and emotions has irrevocably impacted Stevens’ ideology on professionalism and dignity. He even goes to the extent of believing that duty and professional responsibility are required to attain dignity.

Stevens blindly believes in two models—his father and Hayes Society’s definition of a great butler. His idea of duty is shaped by glorifying the self-restraint behaviour of his father. His idea of dignity is, in turn, influenced by the Hayes Society, so he devotedly serves his employer Lord Darlington, whom he believes to be a distinguished gentleman. Stevens is forced into denial when these beliefs come crumbling down.

When Stevens learns that his father is no longer the great Butler he once used to be, he resorts to denial rather than accepting that his father is ageing and can never deliver his duties with perfection as before. Reality strikes hard when Miss. Kenton says, “Whatever your father was once, Mr. Stevens, his powers are now greatly diminished” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 62). Thus, looking at the fall of his only epitome of professionalism, Stevens could not help but adopt denial as his defensive mechanism against the painful reality. Moreover, once again, he goes into his shell of denial when he realises that Lord Darlington’s reputation has been tarnished due to his bad company and bad decisions regarding the world war. As he had always identified his dignity with that of his master, he could not accept his fall from grace. Therefore, Stevens enters into denial and tries to deny working for Lord Darlington on two occasions. The problem with Stevens is his misguided conception of duty and dignity, which employs itself in emotional repression and denial. To address this problem, spatial enquiry is employed to understand the underlying cause of all these issues.

“Within these very walls”—The Absence of Home

Stevens lives in Darlington Hall and also works there as a Butler. Thus, his master’s place becomes his place of residence. Stevens becomes an outsider who purposefully chooses to remain inside. Even though Stevens works and lives in Darlington Hall, he can never identify it as his ‘own’ because he will be a perpetual outsider there. All three places and spaces operate with unity and reciprocity. It is a universal human trait where one feels the “need to identify a sense of self with a physical locale” (Cicognani, 2014). Thus, place plays a pivotal role in shaping one’s identity. Oldenburg (1999) says, “the first place is the home—the most important place of all. It is the first regular and predictable environment…that will have a greater effect upon his or her development”. The lack of first place (home) can be the reason for Stevens’ rootlessness and his inability to make meaningful connections with others. Having spent years inside Darlington Hall (workplace—second place), Stevens has created a false reality that he belongs there and identifies his success with the success of his employer, Lord Darlington. Home is where one’s “territoriality, attachment and belongingness” (Steward, 2000) are shaped. The lack of home can also be equated with the lack of human warmth. Therefore, for Stevens, indulging in professional duties has become the only way in which he could experience a sense of belonging.

The novel begins with Stevens recollecting “a most kind suggestion” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 3) by his current employer Mr. Farraday to take a short vacation to the countryside. Initially, Stevens refuses to take up the suggestion, but after receiving a letter from Miss. Kenton, a previous employee of Darlington Hall, decides to go on a vacation that can be “put to good professional use” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 10). Stevens tries to rationalise that he is going on a vacation for professional purposes, which makes his denial very evident. He also says, “It has been my privilege to see the best of England within these very walls” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 4). For Stevens, Darlington Hall serves as a microcosm of England, and he gladly admits that he has seen more of England inside Darlington Hall, “where great ladies and gentlemen of the land gathered” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 4). This pseudo-identification of himself to the place owned by his employer becomes the foundation of his workaholism, denial, and repression. The reason behind this is the absence of first place—home. The physical environment influences how individuals position themselves within a given space. Spatial experiences, in turn, generate “a sense of personal identity anchored to the surrounding environment” (Cicognani, 2014). As Stevens had spent most of his life in Darlington Hall, there arises a false sense of belonging towards a place in which he will always be an outsider. The flow of spatial energy can become stagnant if there is an absence or lack of reciprocation between the spaces. Throughout the novel, Stevens incessantly tries to replace the absence of ‘home’ by projecting himself as a professionally absorbed person. He equates professionalism with one’s ability to hide emotions. Thus, he lives a life of regret by living in constant denial of his emotions.

In addition, “Home has been shown to be deeply related to people’s sense of personal growth and changes-as a living process or a construction” (Horwitz and Tognoli, 1982). Due to the absence of a home (firstspace), Stevens tries to fill in the gap with the experiences from his workplace (secondspace). Miss Kenton, entering Stevens’ room in Darlington Hall, describes it as “a prison cell” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 53); likewise, as Stevens enters his father’s room, he also feels like “having stepped into a prison cell” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 133). Stevens himself says that his room “is not a room of entertainment. I am happy to have distractions kept to a minimum” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 55). Even in his personal physical space, he refuses to think about anything other than his professional duties. Thus, his confined space inside Darlington Hall only allows him to have a “passive spatial experience” (Rahimi et al., 2018). Every spatial experience is made of “space, event and activity” (Tschumi, 2012), but in Stevens’ case, the secondspace takes over the events and activities of the firstspace. Due to this, his social interactions are very limited, which in turn influences his “cognitive and emotional states” (Graham et al., 2015). Home is believed to be where “basic psychological processes are regularly played out.” (Graham et al., 2015) As Stevens cannot experience these basic processes, he subconsciously adapts a coping mechanism of filling this void of homelessness by being obsessed with his professional duties.

Existing in the Second Place—Repression of physical and mental space

Stevens’ everyday interactions happen only within his second place, which exerts an impending impact on how he perceives himself, others, and his workplace. His ideologies are mostly shaped by hegemony and his consent to exploitation by the ruling class. The protagonist Stevens can be called an “Authoritarian personality” (Adorno, 1950) who is in absolute submission or obedience to someone else’s authority. As a person with authoritarian personality, he firmly believes in a few ideologies, such as dignity, professionalism, and emotional restraint in the workplace. Ideological hegemony is the root cause of these flawed conceptions. Stevens uses terms such as “finest professionals” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 18) and “less distinguished” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 19), which evidently shows how Stevens views other Butlers with regard to the employer they are working for and not for their ‘actual’ professional values. He associates the “moral status of an employer” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 120) with that of the employees. Even though Stevens believes that he belongs to Darlington Hall, he is confined to his workspace, without any social interactions. His restricted accessibility to the secondspace exposes itself in the form of psychological regimentation and emotional restraint, through which the operation of hegemony at both spatial and ideological levels is evident. It has been found that “individuals with an external locus of control are more passive and resigned to the environment” (Wells and Thelen, 2002). Stevens could take control of the workspace only in terms of deciding which objects belong to which place, but the actual control lies with Lord Darlington. Therefore, Stevens experiences conflicted “feelings of belonging, ownership, and control over the workspace” (Vischer, 2008).

The absence of home has limited Stevens’ social interactions only to his workplace. Stevens keeps referring to the “working relationship” when he refers to his relationship with Miss Kenton; his emphasis on this term reveals his belief that “looking for romance” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 53) in the workplace is a “blight on good professionalism” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 53). Apart from the conversations regarding everyday duties, Stevens does not engage in other interactions. His father, who is supposed to be in his first place (home), is also a part of his second place (workplace), so there is a conflict in his interactions, which has affected his relationship with his father. He says that he has started “to converse less and less. So much so that after his arrival at Darlington Hall, even the brief exchanges necessary to communicate information relating to work took place in an atmosphere of mutual embarrassment” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 66). The lack of proper social interaction is the reason for Stevens’ repression, which, in turn, is connected to his repression of physical space. The father-son relationship shows his inability to bridge the gap between the lacking spaces. His relationship with Miss. Kenton shows that he is very conscious of hiding his emotions. He makes every effort to maintain his emotionally restrained behaviour, thinking it would make him a person of dignity. Stevens considered his father a great butler and the personification of dignity, but he fails to recognise the meaning behind their familial relationship. He remembers his father’s death not with a sense of sadness or regret but with a “sense of triumph” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 115) because he believes that he had displayed a “crucial quality of dignity” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 73) on the day his father died. For Stevens, attending to the guests of the conference in Darlington Hall is much more important than comforting his father in death bed. Even though he is seen crying, he denies it and claims, “I do regard it as the moment in my career when I truly came of age as a butler.” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 73). Thus, Stevens’ existence (physically and mentally) only operates around his workplace, limiting him from interacting with others. Therefore, the flow of energy becomes stagnant in the sphere of real space itself.

Exploration of Third Place—“gone beyond all previous boundaries”

Stevens’s decision to go on a vacation begins his journey into third place. It eventually creates a proper flow of energy within the spheres and helps him into the psychological journey in the thirdspace. The third place can be defined as the public space where informal and unexpected social interactions take place. Socially and emotionally repressed Stevens, traversing into the third place and interacting with complete strangers gives him a new perception of his flawed ideologies. He also unlearns and reconstructs his ideologies through interactions. As human “existence is spatial” (Edirisinghe et al., 2011), its influence on human experience is inevitable. The absence of a home and lack of social interactions are the reasons behind Stevens’ workaholism and emotional repression. Stevens is a reticent person who places profession over humanity. Bantering, professionalism, and dignity are the three flawed ideas that form the basis of all his conflicts. Stevens believes that these hegemonically influenced ideologies are the absolute truth, but he relearns those ideologies only through third place interactions and creates his version of the truth.

Stevens says, “I had travelled very little, restricted as I am by my responsibilities in the house, but of course, over time, one does make various excursions for one professional reason or another” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 23), which clearly indicates that he has been using his profession as a way of escaping reality. His journey into third place is “a passage-way between the mundane and the transcendental” (Zhou, 2018). He can feel the transformation within himself and says, “It is perhaps in the nature of coming away on a trip such as this that one is prompted towards such surprising new perspectives on topics one imagined one had long ago thought thoroughly” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 123). He obtains a new revelation through every new place and unlearns the flawed ideologies.

The journey into the landscape also creates a journey into his mindscape. His narration is like a window through which the readers understand both journeys in parallel. The novel is designed in such a way that for every new interaction in the third place, his mind traces back to the past to relate to a similar situation. For instance, when he denies working for Lord Darlington to an unknown chauffeur on the roads, he is taken back to his past when he denied working for Lord Darlington to Mrs. Wakefield. However, as he relates his present and past, he is slowly relieved of his haunting past because interactions in the third place “undoes all that” (Zhou, 2018). It is also important to note how his mind responds to the physical spaces. As Soja mentions, “the way in which individuals interact with space and the methods through which that space is produced, constructed and reconstructed is thus presented as both medium and outcome of human activity, behaviour, and experience.” (Meskell Brocken, 2020). When he encounters the chauffeur and denies working for Lord Darlington, the physical space itself represents his mental state, Stevens says, “I found myself getting lost down narrow, twisting lanes” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 127). But when the space is quiet, he says “the tranquillity of the present setting, it is possible I would not have thought a great deal further about my behaviour during my encounter with the batman” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 128). This shows how physical and mental space always coexist and complement one another.

Unlearning and relearning: finding closure and healing

His interactions with strangers during his trip culminate with his encounter with a stranger at the pier (third place). The third place acts as a tool for relearning, which in turn leads Stevens to understand his physical environment more, thereby letting him revisit his own past from a new perspective. His journey into his mental space can be called his journey into the thirdspace because it “provides a different kind of thinking about the meaning and significance of space and those related concepts that compose and comprise the inherent spatiality of human life” (Soja Edward, 2009). Thirdspace has the potential “not only for re-imaginings of existing structures but a more radical movement within the process of ‘thirding’ towards spaces and conceptions of spaces that recognise and attempt to break with existing power structures and dynamics” (Meskell Brocken, 2020). Stevens lives in denial and constantly represses his emotions, so his journey into the countryside enables him to interact with new people, which helps him unlearn and relearn, through which he accepts his regretful past and moves towards healing.

Coach & Horses and Mr. and Mrs. Taylor’s house are the places where Stevens’ unlearning and relearning occur. Stevens has always maintained a stiff upper lip in regard to interactions in his workplace, so for him, bantering is not a professional quality to acquire. But he tries to learn it as a skill because his new employer is fond of bantering. Every time he utters any witticism, he is not understood properly. However, after his interactions with the people in Coach & Horses and when he goes to the pier at Weymouth, he is astonished at how “they are laughing together merrily. It is curious how people can build such warmth among themselves so swiftly” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 257).

At Mr. and Mrs. Taylor’s house, his misguided ideology of dignity is questioned after learning about Harry Smith’s perception of dignity that it “isn’t just something gentlemen have” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 195). Though the villagers at Mr. and Mrs. Taylor’s house mistake him for a person of political importance, he plays along with the identity rather than telling them he is a butler. Having heard the villagers’ “strong opinion” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 204) on democracy and dignity, Stevens is taken back to his past when he was questioned about democracy. He kept repeating that he could not assist on that matter because he believed his duty was to serve these men of significance and not to develop opinions on such matters. The thirdspace “blurs the limitations of existing boundaries and calls into question the established categories of culture and identity” (Moosavinia and Hosseini, 2017), so Stevens starts asking questions and understands reality. His ability to openly express emotion was his first step in resolving repressed emotions; when Miss Kenton hints about a probable life they might have had together, Stevens admits, “Indeed—why should I not admit it?—at that moment, my heart was breaking” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 251). Another sign Stevens has healed from his past regrets is when he willingly reveals his identity. During the journey, he never enclosed his identity to strangers, but at the pier, he says, “I thought it appropriate to reveal my identity, and although I am not sure ‘Darlington Hall’ meant anything to him, my companion seemed suitably impressed.” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 255). At the end of the chapter, Stevens is seen questioning Lord Darlington’s nobility by acknowledging that his master’s efforts were misguided, just like his devotion towards his master was misguided. Stevens does not readily accept his regret, but only at the pier does he open up to the stranger saying, “I trusted. I trusted in his lordship’s wisdom. All those years I served him, I trusted I was doing something worthwhile. I cannot even say I made my own mistakes. Really—one has to ask oneself—what dignity is there in that?” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 256). As the thirdspace is a “site of liberation” (Zhou, 2018), Stevens feels liberated from his past regrets while emotionally opening up to a random stranger. This social interaction transforms Stevens’ perspective of life itself.

After these social encounters in the third place, Stevens is able to relearn those misguided ideologies and redefine his past experience. As “Thirdspace is a space of negotiation, contestation, and rearticulating” (Edirisinghe et al., 2011), Stevens leaves behind his old self, starts embracing reality, and rearticulates his past with a newly acquired view of life. The inner struggle Stevens faces in accepting the nature of his employer is resolved after various social interactions in the third place. These spatial experiences and interactions are proven to change “people’s behaviour” (Rahimi et al., 2018). Relearning has assisted Stevens in coming to terms with his past, accepting his mistakes, and leaving behind his past. This leads Stevens to closure, which is crucial in resolving his regretful past. “The goal of closure is to reach an endpoint” (Boss and Carnes, 2012), where one leaves behind unpleasant memories and moves on with life, accepting reality. The role of thirdspace as a tool in achieving closure can be further supported by the perception of thirdspace “as a bridge; navigational space; and a transformative space” (Jordan and Elsden-Clifton, 2014). To explain in detail, the thirdspace acts as a bridge connecting Stevens’ present with the past, which needs to be properly addressed to achieve closure. It is also a navigational space, where Stevens explores his physical and mental space, thereby attaining “a sense of personal location” (Gandana, 2008), stabilising his understanding of himself as an ‘individual.’ The thirdspace is indeed a transformative space, where his misguided ideology of bantering being less professional has been transformed into his renewed interest in looking at “bantering more enthusiastically” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 258). From being concerned only about professional duties, Stevens has developed an understanding of the importance of maintaining relationships and “human warmth” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 258). Another important transformation is his acceptance of the downfall of his employer. As Stevens had always identified himself with his employer, he could not accept that Lord Darlington’s thoughts and actions were not as noble as he had thought. However, after opening up about it to a random stranger, he is able to achieve closure. Though Stevens is an outsider, through his journey into the thirdspace, he understands, “without outsiders there are no insiders” (Papastergiadis, 1998). Finally, Stevens is seen leaving behind his past and deciding to “make the best of what remains of (his) day” (Ishiguro, 1989, p. 256).

Conclusion

Through the integration of Oldenburg’s and Soja’s theories, this study has attempted to frame third place as a tool for bridging the gap between home and workplace. Social interactions in the third place have transformed the protagonist and led him to come to terms with reality. Unlearning and relearning are very much a part of learning. Thus, the third place can also be used as a learning space that facilitates an open-minded understanding of ideologies rather than blindly accepting popular beliefs. The protagonist’s journey into the countryside initialises his spatial understanding of people and places. By opening up to a stranger for the first time, Stevens was relieved of his emotional repression and was able to resolve his lifelong conflict of being in denial about his past mistakes. Stevens resolved his conflict by looking at his past from a redefined perspective, which was possible through his psychological journey into the thirdspace. This study also identified thirdspace as a catalyst for achieving closure. This integrated approach carries a greater potential of being used in cognitive development and in understanding human relationships.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article, as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Adorno TW (1950) The authoritarian personality. John Wiley and Sons, New York

Bhabha HK (1994) The location of culture. Routledge, London

Boss P, Carnes D (2012) The myth of closure. Fam Proc 51(4). https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12005

Calinescu A (2020) The invisible hand in the remains of the day. Philologia 18(1):51–63. https://doi.org/10.18485/philologia.2020.18.18.5

Cicognani E (2014) Psychological home and well being. Available via Academia.edu https://www.academia.edu/12581952/Psychological_Home_and_Well_Being. Accessed 22 Feb 2023

De Chavez J (2021) The symbolic fiction of Mr. Stevens: a Lacanian reading of Kazuo Ishiguro’s the remains of the day. Explicator 79(4):174–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00144940.2021.2005521

Duangfai C (2018) Psychological disorder and narrative order in Kazuo Ishiguro’s Novels. Dissertation, University of Birmingham

Edirisinghe C, Nakatsu R, Cheok A, Widodo J (2011) Exploring the concept of third space within networked social media. In: Anacleto JC, Fels S, Graham N, Kapralos B, Saif El-Nasr M, Stanley K. (eds) Entertainment Computing—ICEC 2011 Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6972. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 399–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-24500-8_51

Ekelund BG (2005) Misrecognizing history: complicitous genres in Kazuo Ishiguro’s the remains of the day. Int Fiction Rev 32(1–2):70–91

Furst LR (2007) Memory’s fragile power in Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Remains of the Day” and W. G. Sebald’s “Max Ferber”. Contemp Lit 48(4):530–553. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27563769

Gandana I (2008) Exploring third spaces: negotiating identities and cultural differences. Int J Divers Organ Communities Nations Ann Rev 7(6):143–150. https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9532/CGP/v07i06/58032

Graham LT, Gosling SD, Travis CK (2015) The psychology of home environments. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(3):346–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/174569161557676

Horwitz J, Tognoli J (1982) Role of home in adult development: women and men living alone describe their residential histories. Fam Relat 31:335

Ishiguro K, Kenzaburo O (1991) The novelist in today’s world: a conversation. Boundary 2 18(3):109–122. https://doi.org/10.2307/303205

Ishiguro K (1989) The remains of the day. Faber and Faber limited, UK

Ishiguro K (2008) Conversations with Kazuo Ishiguro. In: Shaffer Brian W, Wong Cynthia F (eds) Literary conversations series, Vol 18. Google Books

James D (2009) Artifice and absorption: the modesty of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. In: Matthews S, & Groes S (eds). Kazuo Ishiguro: contemporary critical perspectives bloomsbury, pp. 54–66

Jordan K, Elsden-Clifton J (2014). Through the lens of third space theory-possibilities for research methodologies in educational technologies. In: International Conference on Computer Supported Education, vol 2. Scitepress pp. 220–224. https://doi.org/10.5220/0004792402200224

Khalaf MFH (2017) Reconstructing the past as a means of rationalizing the present: a study of Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of The Day (1989). Int J Appl Linguist Engl Lit 6(4):173–183

Lang JM (2000) Public memory, private history: Kazuo Ishiguro’s The Remains of the Day. CLIO 29(2):143

Leeb Claudia (2021) Adorno and Freud meet Kazuo Ishiguro: the rise of the far right from a psychoanalytic and critical theory perspective. In: Jeremiah Morelock (ed.) How to critique authoritarian populism: methodologies of the Frankfurt School. Leiden, Netherlands. pp. 200–219

Lefebvre Henri (1991) The production of space. Basil Blackwell Ltd, UK

Meskell Brocken S (2020) First, second and third: Exploring Soja’s Thirdspace theory in relation to everyday arts and culture for young people. In: Ashley T, Weedon A (eds). Developing a sense of place: the role of the arts in regenerating communities, UCL Press. pp. 240–254. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv1453kbw.23

Moosavinia SR, Hosseini SM (2017) Liminality, hybridity and “Third Space:” Bessie Head’s a question of power. Neohelicon 45(1):333–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11059-017-0387-8

Myers Pete (2012) Going home: essays, articles, and stories in honour of the Andersons. Oak Hill College, London

Nakajima A (2018) What Stevens does not narrate: narrative strategy for challenging Nostalgia in The Remains of the Day. Stud Engl Lit Region Branch Issue 10:275

Oldenburg Ray (1999) The great good place. Marlowe & Company, New York

Papastergiadis N (1998) Dialogues in the diasporas: essays and conversations on cultural identity. Rivers Oram Press, London

Rahimi BF, Levy RM, Boyd JE, Dadkhahfard S (2018) Human behaviour and cognition of spatial experience; a model for enhancing the quality of spatial experiences in the built environment. Int J Ind Ergon 68:245–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ergon.2018.08.002

Shaffer Brian W (1998) Understanding Kazuo Ishiguro. University of South Carolina Press, Columbia

Soja Edward W (1996) Thirdspace: journeys to Los Angeles and other real and imagined places. Mass: Blackwell, UK

Soja Edward W (2008) Taking space personally. In: Warf B, Arias S (eds) The spatial turn: interdisciplinary perspectives, 1st edn. Routledge, London, pp. 11–35

Soja Edward W (2009) Thirdspace: toward a new consciousness of space and spatiality. In: Ikas Karin, Wagner Gerhard (eds) Communicating in the Third Space. Taylor & Francis, UK

Stevenson R (2005) The Oxford english literary history: volume 12 the last of England?. Oxford University Press, UK

Steward B (2000) Living space: the changing meaning of home. Br J Occup Ther 63(3):105–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022600063003

Webster Thomas Diane A (2013) Identity, identification and narcissistic phantasy in the novels of Kazuo Ishiguro. Dissertation, University of East London. https://doi.org/10.15123/PUB.3451

Tschumi B (2012) Architecture concepts: red is not a color. Rizzoli, New York

Vischer JC (2008) Towards an environmental psychology of workspace: how people are affected by environments for work. Archit Sci Rev 51(2):97–108. https://doi.org/10.3763/asre.2008.5114

Wall K (1994) “The Remains of the Day” and its challenges to theories of unreliable narration. J Narrat Techniq 24(1):18–42. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30225397

Wang L (2020) On reconstruction of the past and salvation-seeking at the present through memory in The Remains of the Day. J Beijing Int Stud Univ 42(1):83

Wells M, Thelen L (2002) What does your workspace say about you? Environ Behav 34(3):300–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916502034003002

Yi CC (2016) A study of loss and memory in Kazuo Ishiguro’s never let me go, remains of the day, and he buried giant. Quint Interdiscip Q North 9(1):134

Zhou Xiaowei V, Pilcher N (2018) Revisiting the “third space” in language and intercultural studies. Lang Intercult Commun 19(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2018.1553363

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Narayan Jena, Assistant Professor of English Literary Studies (Senior Grade), Sri Sri University, Cuttack, Odisha, India, for his invaluable linguistic support and assistance in proofreading this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. So informed consent is not relevant.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maran, A., J, M.R. Integrating Oldenburg’s concept of place and Soja’s concept of space: a spatial enquiry of denial, repression, and closure in Ishiguro’s “The Remains of the Day”. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 186 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01676-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01676-0