Abstract

During the Republican era, when China faced internal and external difficulties and was impoverished, social education was considered crucial to revive and strengthen the country. After social education was introduced to China from the West, many universities participated in social education and became the main promoters and implementers of social education, giving it localized characteristics. Thus far, there remains a void in the social education of Chinese universities in the English-speaking world. The present study explores the historical motivations for universities in the Republic of China (ROC) to join the wave of social education development from 1912 to 1949. Herein, Yenching University, Jiangsu Provincial College of Education, National Sun Yat-Sen University, and National North-West United University were selected for case studies to demonstrate the methods and achievements of social work, literacy, political, and life education through the establishment of rural experimental areas. The “university experimental area” model of education created by universities differs from other models and reflects a close relationship between the university and the state and society. This model makes up for the shortage of foreignization, aristocracy, and urbanization of school education within the specific time and space. Moreover, the model enriches the connotation of “ education throughout society”. In addition, the social education experiences of universities in ROC provide a valuable solution for exploring rural education, rural renewal, social construction, and national governance. Furthermore, it is one of the historical preludes of China’s rural revitalization strategy in the new era as well as a practical reference for countries in the world with similar problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Social education emerged against the background of traditional Chinese social edification going out of control and the Eastward transmission of Western learning. By nature, Chinese traditional social edification is a “ruling skill” of “political and educational integration.” It aims at ensuring that people “abide by discipline and law” from a long-term stability perspective. The content of edification was narrow, single-minded ethics and morality. However, the collapse of the feudal dynasties resulted in the decline of traditional edification. Following the Second Opium War, class and ethnic contradictions sharply intensified. Subsequently, the activity bases of missionaries penetrated from the coast into the interior, adding 11 ports of commerce in succession (Xiong, 2011, p. 6). Accordingly, the missionaries established new-style schools, newspaper offices, church hospitals, and so on, for the dissemination of Western sciences. More importantly, Western translation and publishing institutions began to emerge in large numbers, and the influence of Western learning gradually expanded from cities to social grassroots. Furthermore, Chinese educators who studied abroad introduced educational ideas from Germany, France, Denmark, and other Western countries to China (Bailey, 1990, p.192). With the spread of Western learning and the intensification of external and internal problems, an increasing number of intellectuals realized that relying solely on school education to train talents to save the country and the people is not sufficient. “Social education is a new cause due to the slow effect of school education, and it is the only way to save China from peril” (Zhou, 1933, p. 1). Some researchers even exclaimed that “If we fail to achieve social education, China will not be saved” (Lu, 1933, p. 4).

Some scholars believe that the beginning of social education in China is marked by the creation of the Department of Social Education by Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940) in 1912. Wang & Wang (1992) argued that Mr. Cai Yuanpei advocated the establishment of the Department of Social Education because he was deeply influenced by German social education during his stay in Germany. “Mr. Cai Yuanpei returned from his studies in Germany and introduced German social education theory into China” (Wang & Wang, 1992, p. 43). Accordingly, the following questions were posed: Did the term “social education” and its theory expand to China from Germany? Was it first introduced by Cai Yuanpei? However, an examination of the origins of social education in China during the Republican era shows that this was not the case.

The term “social education” was first introduced to China by the Japanese educational circles, judging by the way it was mostly translated from Japanese sources. Gradually, the term was introduced to the Chinese people with the translation of various foreign educational theories. Yamana Jiro’s Theory of Social Education (1892) and Sato Yoshiharu’s The Recent Social Education Law (1899) marked the emergence of the notion of social education in Japan (Liang, 1994, p. 3). Between 1896 and 1907, there was a surge of Chinese academics studying in Japan, with international students studying and introducing Japanese education and translating Japanese versions of the Western socio-political theory. During this period, The World of Education, a professional educational journal, was founded in China (May 1901). Other journals such as Youxue yibian also introduced Japanese educational theory. In these articles, the Chinese people understood, extended, and used the term and ideas of “social education” in light of the social situation in China, in addition to introducing Japanese social education ideas. Gradually, with the deepening of this publicity, the concept of Chinese social education developed.

Educational journals in modern China used the term “social education” before 1912, indicating that the term was not introduced by Cai Yuanpei from Germany and that it was an imported term, translated from Japanese. Cai Yuanpei intended to set up the Department of Social Education to “promote adult education and remedial education,” as there were “too many elderly school leavers” in China (Gao, 1991a, p. 707). During his tenure as the President of Peking University, he established Peking University Civilian Night School, which was the first attempt to implement social education in Chinese universities. Schools were connected with society (Civera, 2013, p. 200). Since then, many universities and educational associations have participated in social education development. Teachers and students have become the main promoters and implementers of social education. From 1912 to 1949, universities imparted social education mainly by establishing rural services and educational experimental areas.

This study highlights the historical motivations for, case studies concerning, and university participation in social education development in the ROC from 1912 to 1949. The central questions posed in this study are as follows: which typical measures were implemented by Chinese universities participating in social education during the Republican era? What is the significance of these measures? What lessons can be learned from the experiences of Chinese universities for social education in universities in other countries in the current global context?

Literature review

Many scholars have emphasized that social education in universities is a viable and effective form of extending educational content. According to Wang (2003), “Modern social education mainly refers to a purposeful, planned, and organized educational activity outside the school system, which is promoted by the government and assisted by the promotion of private and non-governmental organizations to improve the quality of the out-of-school people and all citizens and to use and set up various cultural and educational institutions and facilities.” Giroux et al. (2012) considered schools as the agents of socialization. The author claimed that schooling should be linked to similar attributes in the workplace and other socio-political spheres. Gulová et al. (2017) asserted that social education aims at shaping the optimal means of living of individuals and social groups and facilitates enculturation and socialization.

Universities can expand the connotations of social education and its functions. Academic research has focused mainly on the functions of social education. Zhang (2008) explored the ways to realize the social education function of universities. Universities implement their social service functions to conform to their school style and the specificity of their social service functions. Wang (2013) argued that “the social service of universities is mainly an educational service, and the essence of university social service is social education.” Furthermore, the author stated that social service functions “make use of the human resources (students and teachers), material resources (facilities and institutions), and activity resources (social practice and cultural benefits) of the university, in addition to promoting university education to the society in a purposeful, planned, and organized way, thereby stimulating and meeting the social public’s demand for education through the promotion and expansion of university education and realizing the standardization, organization, guidance, and assistance of social education.”

Historical studies of social education cover two aspects. One is the study of typical social educators and their educational thoughts. Wang (2021) explored Tao Xingzhi’s idea of “creative social education”. The other aspect is the review of the origin and policy evolution of Chinese social education (Naren & Xiang, 2022; Shao, 2020; Wang, 2020).

Chinese academic research on social education originated in Japan and Germany. However, the United States and other countries are also world leaders in research on social education. Neumann (2017) examined the relation between American social education and the political participation of adolescents. The author documented that the failure of social education in the United States has led to the low political participation of young people. Kutschera et al. (2019) discussed the core elements of rural social work in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia and the effect of their rural work initiatives on the Philippines.

Social services in Chinese universities began later than those in Europe and America. Duan (2005) mentioned that building inclusive public entrepreneurial universities, continuing entrepreneurship, and strengthening public service require social education experience in the United States. According to Zhang and Dong (2005), the functions of universities in the medieval period and contemporary universities participating in social education and serving society should begin with establishing the concept of educational service. Moreover, university students should go out of campus and integrate into society.

In recent years, some European countries have started offering degree courses in social education. Compared with degree programs in other European countries, the bachelor’s degree program in social education in Spain is relatively new (Pallisera et al., 2013). Social education has been tried in the Spanish Second Republic. (Bárez, 2002, pp.155–178) Royal Decree 1420/1991, of August 30, by which the Official University Degree of Diploma in Social Education is established, was published in the BOE on Thursday, October 10, 1991. This is the legislation with which Social Education begins in Spain (BOE, 1991). The incorporation of social education as a university subject represented a crucial step in establishing the profession, leading to its social recognition (Noell et al., 2009).

In general, several areas exist for research on social education in Chinese universities: first, Chinese social education was influenced by Japan and Germany; hence, considerable similarities exist in terms of concept, content, and institutions. However, social education has been given a “Chinese character” owing to the special political background of the ROC. In addition, there remains a void in Chinese social education in the English-speaking world. Second, domestic scholars have not focused much on social education in universities. Only a few studies have explored social education in Chinese universities. Accordingly, this study considers Chinese universities as the research subject and social education as the keyword to classify first-hand materials and explore the development path of universities participating in social education in the ROC. Through this analysis, the study aims to present the historical experience and lessons learned concerning social education in Chinese universities for discussion in academic circles at home and abroad.

Historical motivations for university participation in social education

During the Republican era, China faced internal and external challenges. Chinese society was eager to change the social situation, improve the daily lives of the people, and raise the quality of the population through a new form of education. Accordingly, social education became mainstream education at the time, and educators from universities and educational societies participated in social education activities. There are three historical reasons for the emergence of social education in the universities of the ROC.

The first reason is the poor quality of the people. In 1902, Liang Qichao published the New People’s Theory. In this book, the author mentioned that people should be knowledgeable, educated, socially virtuous, liberal, and self-respecting, in addition to having a sense of crisis and concern for the country’s peril. Some reformers suggested that the implementation of the reform should be based on the people. During his tenure as the President of Peking University, Cai Yuanpei established Peking University night schools to attract lost scholars to study and opened a precedent for universities to participate in social education.

In 1912, a group of young students with high ideals established the Peking University Civilian Education Lecture Group. They preached public morality, health, and culture. “Since the May Fourth Movement, students have mostly run civilian schools to popularize knowledge and vocational education for people outside the school. Cai Yuanpei considered it a positive aspect” (Gao, 1991b, p. 287).

The second reason is the dysfunctional development of society. In the 1915 New Culture Movement, educators studying abroad brought foreign advanced ideas and educational systems back to China. Furthermore, an increasing number of people considered social education as a means of improving social disorders, given the spread of the concept of “society” abroad. Fu Baochen (1893–1984), an educator who returned from studying abroad, opined that “rural education is a prerequisite for improving social and economic conditions” (Chen & Fu, 1994, p. 17). The Peking University Civilian Education Lecture Group also proposed social reform through the following topics: “improving society and crying,” “what is new morality,” “the harm of smoking,” “getting rid of superstition,” “why read,” “freedom and equality,” and so on. The Peking University Civilian Education Lecture Group focused on the ways to prepare students to engage with these and not on developing their values, character, or interpersonal behaviors. (Barton & Ho, 2022, p. 3).

The third reason is the defects of the education system. Many returnees followed foreign educational philosophy and school management systems. However, the education system was “imitating Japan first, studying America later, neither of which is suitable for the needs of the country” (Mao & Tang, 1992, p. 39). This kind of school education, which failed to conform to the national conditions, affected society and talent training for some time. However, achieving the educational ideal of improving the backward situation in China, in the long run, seemed difficult. In May 1918, the Chinese Vocational Education Society established the Chinese Vocational School and proposed that “given the shortcomings of today’s education in China, it is insufficient for learning to apply.” According to Tao Xingzhi (1891–1946), China needs social education to “make up for the lack of normal school education.” In 1919, the Peking University Civilian Education Lecture Group proposed to “subsidize what school education has failed to do.”

Gradually, social order and development in the ROC were adversely affected, the drawbacks of school education emerged, and universities were unable to fulfill their educational and social functions. Therefore, the government and educators tried to improve society and raise the quality of the people through social education. To some extent, university participation in social education has realized the functions of opening up people’s intelligence, improving society, making up for the lack of schools, and expanding the effectiveness of universities. Undoubtedly, the university is an essential force for promoting social education development.

Case analysis

Communists, rural reconstructionists, and the League of Nations proposed solutions from different perspectives to address the varied social problems of the ROC. Suzanne Pepper (1996) argued that the solutions advocated were broadly similar to decentralized, locally oriented, and locally financed schools with flexible standards and curricula geared to the genuine educational needs of the rural majority. Unlike these solutions, universities can implement social education primarily through the creation of rural experimental areas. This study selected four universities that were outstanding in social education to depict the influence of university participation on social education in the ROC.

Social work education: the case of Yenching University

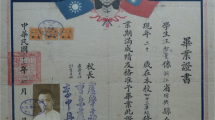

Concerning social service, the Christian University makes an important contribution. American educator, John Leighton Stuart, who established Yenching University asserted that Yenching University should focus on the moral development of its students and create useful people to serve the country and society. At the beginning of its establishment, Leighton Stuart began exploring means to conduct social services and organized Yenching University to participate in social works such as relief, disaster relief, and community assistance. From 1924 to 1926, Yenching University formed a Local Service Group to carry out various social support activities, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Yenching University placed additional emphasis on the sociality and practicability of the courses and vocational training by establishing a major in industrial tanning and offering courses such as child nutrition in line with Chinese realities. These courses instilled in students the idea of social service and contributed to the building of rural China (Lutz, 1987, p. 266).

In 1922, Yenching University established the Department of Social Science to implement social work education and designed professional courses on labor welfare groups, women’s groups, and social service and social relief groups. In 1925, the Department of Sociology has renamed the Department of Sociology and Social Services. Moreover, a short-term social services discipline (class) was added to continuously enhance the relevance of social services. In 1927, the Department of Sociology added a “Correspondence Course in Social Services.” Furthermore, the department co-organized the “Crash Course in Social Services” with the Religious College to nurture practical and highly specialized talents, as well as effectively serve China’s social undertakings. Since then, the Department of Sociology has successively established social research and service bases at the grass-root level, such as Ching Ho Rural Experimental Area.

Ching Ho Rural Experimental Area of Yenching University was a typical representative of colleges and universities to serve and transform rural society. The Ching Ho experiment lasted 9 years and focused on the three dimensions of the implementation of the transformation work—economy, education, and health. Furthermore, a considerable part of the rural construction experiments during the Republican period was focused on the development of rural education. By contrast, rural economic construction was considered the top priority of all the work in the Ching Ho Rural Experimental Area. Through on-the-spot social investigation, teachers and students of Yenching University concluded that “when the livelihood is difficult, farmers think about everything from the monetary perspective; the central idea of farmers’ lives is how to make more money on their land. Therefore, we must make dedicated efforts to improve the lives of the rural people from the economic aspect” (Xu, 1933, pp. 1–13).

Accordingly, the experimental area initiated rural economic construction through the establishment of cooperatives and cooperative farms, as well as the development of rural industries as the main contents. At the end of 1930, the first cooperative in the Ching Ho Experimental Area was established in Tangjia Ling Village. From then on to 1936, the experimental area guided the establishment of 29 cooperatives. These 29 cooperatives mainly operated credit businesses, consumption businesses, and warehouses. Credit cooperatives obtained funds through savings businesses. In terms of credit loans, 34.6% were loaned to individuals, and 65.4% were loaned to cooperatives operating cooperative stores and farms.

Furthermore, cooperative farms are another crucial undertaking of economic work in the Ching Ho Experimental Area. Cooperative farms provided guidance and promoted agricultural varieties and technologies to facilitate agricultural income. The Ching Ho Town followed old approaches to agricultural technology. It was unaware of improvements and unable to cooperate; thus, it could barely undertake prevention and relief measures for flood, drought, and pest invasion. According to Yenching University Rural Work Seminar (1934), “the field experiment is a way for Christian University to select a special area for agricultural extension experiment through technical demonstration and to persuade and guide farmers to adopt new varieties and new technologies with examples. This method is suitable for farmers who are conservative and exhibit a poor ability to accept new things.” Through field experiments, teachers and students from the Department of Sociology at Yenching University successfully changed the concept of local farmers, led the cooperative farms to successfully improve a considerable amount of saline-alkali land, and planted high-yield economic crops.

The development of village industries was another attempt at undertaking economic work at the Ching Ho Experimental Area. These industries included wool weaving, homespun printing, hand-woven carpets, and the manufacture of peanut butter for the young female workforce in families. Students were sent out to learn wool weaving techniques. After completion of their studies, “family wool weaving training classes,” which served as training and factory production, were established in the experimental area to train villagers. Local women acquired the skills and each woman earned 5–7 yuan per month, thereby supplementing the household income of the farmers (Xu, 1931).

Easy literacy education: the case of Jiangsu Provincial Education College

Following the establishment of the Ministry of Education during the Republican period, a series of public education, remedial education, and national education laws were issued to vigorously eradicate illiteracy. The initiative received positive responses from universities and people from all walks of life. Among these, Jiangsu Provincial Education College was an outstanding representative of local society’s transformation through popular education. Jimmy Yen, a renowned civilian educator, actively responded to the national literacy movement and established rural experimental areas, calling for “the elimination of illiteracy and the creation of a new people.” Moreover, he bequeathed to the world the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (Hayford, 1990, p. 93).

Jiangsu Provincial Education College, located in Wuxi, was the first higher education institution in China to train teachers for popular education. Since its inception in 1928, Jiangsu Provincial Education College has cultivated countless popular education talents, which positively influenced Wuxi and the country, becoming one of the centers of the modern popular education movement.

Considering the success of the popular education practice, the Ministry of Education issued a ministerial order requiring all provinces and cities to consider it as a model to implement popular education. In addition to the government’s recognition, Jiangsu Provincial Education College was highly regarded internationally. In 1931, the education delegation of the League of Nations came to China. They inspected the Jiangsu Provincial Education College and other experimental areas of popular education such as Dingxian County and inferred that adult education in China was most satisfactory.

Since the establishment of Jiangsu Provincial Education College in 1928, the college has begun a popular education experiment. The special research and experimental department were formed by professors of the college, and research and experimental meetings were held every year on special problems in popular literacy education and popular reading materials. Figure 2 shows a photograph taken after one of these meetings. Jiangsu, an economically developed region of modern China, has been rich since ancient times; however, the distribution of educational resources remains uneven. Moreover, the illiteracy rate in Wuxi continues to be high.

In 1932, the Jiangsu Provincial Education College established the Beixia Popularization Experimental Area in the second district of Wuxi County. It encompasses an area of 138.5 square kilometers in three towns and 342 villages, with 43,588 acres of taxed land and a population of 5,893 households comprising 25,392 people. The ratio of males to females was 114.4:100. Furthermore, 26% of the population were subsistence farmers, 51% were semi-subsistence farmers, and 23% were sharecroppers. Among the population aged over 7 years, 72.72% were uneducated, 24.93% were educated for 1–6 years, and only 2.35% were educated for more than 6 years (Gao, 1936, p. 35). The number of uneducated people was large. Accordingly, the Beixia Popularization Experimental Area aimed to primarily provide literacy education to the people in the area to enhance the literacy rate.

Literary education in the area was mainly handled by popular schools. In 1932 and 1933, four popular schools were established and thousands of people were enrolled. From the third phase, classes for children and youth commenced. The teaching methods were categorized into fixed and activity establishments. The children’s classes taught simple phonetics and literacy. The youth classes dominated by rural men and women aged over 16 years offered subjects such as Chinese language, agriculture, numeracy, agricultural business, and design, in addition to some life lessons, with a focus on agricultural work.

The Beixia Experimental Area recorded outstanding achievements in the literacy movement. In 1932, 1245 adult students were enrolled in the two phases of popular schools, constituting approximately 5% of the region’s population. The number of adult students increased to 1270 and 1224 in 1933 and 1936, respectively. Over the years, 5261 people acquired education, constituting more than 20% of the region’s population, in addition to the original 20%. Thus, nearly half of the population acquired education (Zhu & Wang, 2007). Moreover, literacy classes established in folk schools had a large female enrollment rate, with 68% of women being enrolled in 1932. Accordingly, it can be inferred that popular schools have adequately considered gender equality while popularizing literacy education.

Political and self-defense education: the case of Sun Yat-sen University

In the 1930s, Japan deliberately launched a war of aggression against China. In response to the Party’s call to go to the countryside, Sun Yat-sen University established a Rural Service Experimental Area to publicize anti-Japanese and national salvation. Zheng Yanfen (1936a), the director of the service area office, stated the following: “Our highest purpose in serving the countryside is to promote the development of the university’s rural undertakings, especially in the implementation of mass education and the work of national salvation, in the hope of cultivating the national force and preparing for the struggle of self-defense against war.”

The Rural Service Experimental Area of Sun Yat-sen University was formally established on April 1, 1936, and lasted until the Japanese invasion of Guangzhou in October 1938. The service area targeted 10 villages: Cencun, Changban, Shangyuangang, Xiaogang, Dongpu, Shipai, Xiancun, Liede, Yangji, and Sibeidi. Figure 3 shows the rural service experimental area of Sun Yat-sen University.

In 1936, the site of Sun Yat-sen University, Shipai, was surrounded by rural areas, which provided a prerequisite for its rural service experiment, and the establishment of an experimental area near the university made it easy for staff and students to go to carry out their work. The students of Sun Yat-sen University then used the ten villages around Shipai as the experimental area.

The service area conducted both research and practical work. The research work encompassed rural politics, agriculture, construction, and economics, whereas the practical work encompassed the national rejuvenation movement (the promotion, training, and organization of the national rejuvenation movement) and war preparation training.

The work was broadly categorized into two phases. The first phase lasted for 6 months from April 1936 to October 1936, and the second phase was from October 1936 to August 1937. The first phase focused on investigation, aiming at familiarizing with villagers and the rural situation to establish a sound foundation for the experiment. During this phase, newspaper offices and public night schools were established, agricultural technology was supported, health services were implemented, and visits were conducted between families and villages. Once the villagers developed trust in the service experiment and accepted guidance, the second phase was initiated (Zheng, 1936b, p. 1).

The second phase focused on the implementation of four major training programs in fields, namely political, economic, self-defense, and cultural, with more emphasis on political training, which was also the most successful (Zheng, 1936b, p. 36). Notably, villagers were traditionally “submissive.” They were detached from politics and had no political enthusiasm. To address this issue, political organizations such as service groups, the strong young men team, and so on, were established in the experimental area. The political organizations conducted educational work to increase villagers’ political knowledge and improve their political enthusiasm.

Night schools and singing and drama (see Fig. 4) groups were considered the most popular and effective ways for political organizations to conduct political education activities in villages. Accordingly, 11-night schools were established in the experimental area, comprising more than 1500 students. Most of them were divided into high, middle, and junior levels, and some were divided into high and junior levels. In addition to extracurricular activities, the basic subjects were divided into language training, general knowledge training, and life guidance. According to Zheng (1936b, p. 1), “the textbooks of night schools in all townships, whether in the national language, general knowledge, or singing, are full of the awareness of resistance to the enemy and salvation, and even arithmetic often takes the number of lost land as the theme.” After several months of work, the upsurge in the rural public’s enthusiasm about saving the country and the people were unexpected (Zheng, 1936a, p. 223).

The service area lasted more than 1 year and recorded remarkable achievements in self-defense training. Zheng Yanfen (1936b, p. 54) asserted that “if all rural work does not start with young people, there is no assurance.” Therefore, self-defense training in the service area was mainly limited to young men. The approach to self-defense training was roughly divided into technical and spiritual aspects. Technical aspects referred to guerrilla tactics, national arts, and so on. The goal was to form the people’s armed forces for conducting guerrilla warfare and disrupting the enemy’s rear when war emerged. Furthermore, the service area organized national skills and sports competitions in various villages. The spiritual aspect focused on teaching the significance of self-defense and the wisdom of defense.

Life skill education: the case of National Northwest United University

Following the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, the universities in Beiping and Tianjin areas moved to the mainland. Gradually, the areas were formed into two consortia: National Northwest Associated University and National Southwest Associated University. The National Northwest Associated University was established by the National Beiping University, National Beiping Normal University, National Beiyang Engineering College, and Hebei Provincial Women’s Normal College in Northwest China. The Northwest United University was responsible for cultivating talents and scientific research, in addition to serving the society of the border provinces.

The Northwest United University served the society with social education as its focus. Northwest China was remote, covering a wide area of agricultural and pastoral areas; however, people in these areas possessed less scientific and cultural knowledge. Accordingly, the Northwest United University specifically emphasized rural social education work. Moreover, its main objective was the establishment of rural social education teaching areas.

The Northwest United University conducted numerous social service work focused on the rural social education teaching area, among which the effect of life skill education was the most remarkable. The central work of life skill education in rural social education teaching area was categorized into two aspects: popularizing basic life knowledge and training life skills.

Teachers and students of the Northwest United University spontaneously organized the publication of farmers’ tabloids, introduced some basic life knowledge and women’s knowledge through tabloids and films, and publicized the concept of science and health for popularizing basic life knowledge. Figure 5 shows the Dujacao Film Centre.

In addition, the Northwest United University experimented with phonetic symbols to eliminate illiteracy in the children’s class at National Protection School and the women’s class at Central People’s School attached to the teaching area. This experiment aimed to address the problem wherein children and women were unable to read and learn life knowledge.

According to the teaching staff’s experience, children and young women of a certain age, who did not take leave, studied the method of phonetic symbols within 2 or 3 months and read popular phonetic reading materials, which shortened the learning period (NNUHRG, 2014, pp. 544–559).

The public health training activities were mainly held for training life skills. A “public health tour” was organized to coincide with the spring vaccination work. Students were required to ask their parents and neighbors to get the vaccination or listen to the lectures. The participants were enthusiastic. The wall charts explained the significance of public health and the prevention of epidemics such as cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. Women were made aware of the aspects related to pregnancy. After the sanitation tour, the teaching area provided instructions on hygiene in the nearby villages, such as village grooming, improvement of toilets, and street sanitation. The villagers expressed their acceptance and actively undertook rectification according to civilized sanitary conditions.

China was founded on agriculture, and the lifeline of the nation lies in the countryside. In modern China, the rural society was internally and externally destroyed, and the national life was reduced to a moribund state. In the specific context of the Republican era, out of their consciousness for saving the nation, the four universities established experimental areas in the countryside to conduct social improvement work from the political, cultural, economic, construction, and health perspectives. Accordingly, a series of attempts were made to build up the countryside. The focus of social education and achievements of the four universities differed, reflecting the school-running philosophy and realistic demands of each university.

John Leighton Stuart, President of Yenching University, was an American. His school-running philosophy was deeply influenced by the Western ideology of “educational methods pay attention to practicality” and “learning for application.” Therefore, he embodied an obvious pragmatic value orientation, emphasized the close connection between the school and society, and considered the rural economic construction of the experimental area as the focus of work to meet the actual needs of Chinese society. This differed from the philosophy of Jiangsu Provincial College of Education, which focused on rural education in the experimental area. The prevalence of education in ancient China was low, and the illiteracy rate continued to be high in the ROC. Furthermore, illiteracy was a major obstacle to opening up a new society and reviving the nation. Thus, the Jiangsu Provincial College of Education was dedicated to literacy education to reduce the illiteracy rate. Anti-Japanese and national salvation became the theme of the time when National Sun Yat-Sen University built the experimental area. The authorities of Sun Yat-sen University believed that the crisis could be saved only by stimulating, training, and organizing the strength of the rural masses. Accordingly, the experimental area was established to primarily promote anti-Japanese salvation and mobilize the masses to defend the country. However, its remote location in the interior of China and the underdeveloped economy resulted in the low cultural level of the population. Thus, Northwest United University’s social education work focused on bringing scientific concepts of life and healthy hygiene habits to people.

Conclusion and discussion

In modern China’s contact with the world, traditional social edification gradually became unmanageable. With the dissemination of Western learning to the East, China adopted the Western school education system. However, the shortcomings of this new education system were increasingly exposed after the 1920s, focusing on foreignization, aristocratization, and urbanization. The new education system clearly could not adapt to or meet the needs of the peasants, who constituted the vast majority of China’s population, and the development of the countryside. With the intensification of internal and external problems, the exploration of new educational systems and models became imperative. During this period, social education flourished in China.

The universities of the ROC have been involved in social education to save the nation, becoming the main practitioners of social education. As an important measure of social education, the universities of the ROC established rural experimental areas for people’s education and social transformation. Through research in experimental areas, university teachers and students combined their strengths to conduct targeted education and transformation activities in rural politics, culture, agriculture, health, and construction. Furthermore, Yenching University, Jiangsu Provincial Education College, National Sun Yat-Sen University, and Northwestern United University have made outstanding achievements in social work, easy literacy, political and self-defense, and life skill education. These universities have become representatives of the Republican universities’ involvement in social education. In addition to these four universities, social education was implemented simultaneously in the Civilian Education Lecture Group of Peking University and the Civilian Education League of Beijing Higher Normal University (the predecessor of Beijing Normal University). Teachers and students of the university went out of the campus to the countryside and the civilians and educated the people with their knowledge, thereby presenting a wonderful example in the history of modern Chinese higher education.

The university’s efforts to practice and promote popularization and development of social education under extremely difficult conditions reflected a sense of mission and cultural education consciousness of university teachers and students. Furthermore, the university’s involvement in social education has profoundly influenced modern Chinese history, local society, and the university’s teachers and students. University teachers and students reached out to society and the countryside by establishing experimental service areas and creating experimental educational areas to serve the public and grow in their learning through practice. Moreover, university participation in social education in the ROC brought university education into contact with the lives of the largest majority of Chinese farmers. This approach eventually helped in addressing the problems of rural education, agricultural technology, and living and sanitary conditions, as well as inspired and nurtured national consciousness and patriotism in the general population, thereby providing ideological security for the victory in the war.

The “university experimental area” model of education created by the universities between 1912 and 1949 for national salvation differed from other models and reflected a close relationship between the university and the state and society. In the social educational practices of university teachers and students, education and life, as well as school and society, are closely linked. Education is aimed at solving social and life problems, and thus, the boundaries between school education and social education are gradually blurred. This model provided flexible and varied forms of education for people with different levels of education. Furthermore, the model made up for the shortage of foreignization, aristocracy, and urbanization of school education within a specific time and space and made it possible to achieve some success in popularizing education and transforming society. However, the universities failed to explore programs with widespread applicability in their experiments, reflecting the challenges in social education in Republican universities. Thus, it can be inferred that social education and national renewal are holistic and systematic projects requiring overall planning and investment of human and material resources at the national level, as well as the participation and collaboration of all forces. However, the political and social conditions of the Republican era made these tasks challenging. Chinese universities’ social education annotates and enriches the meaning of “education throughout society” with a short history. Overall, the experience of the ROC provides a reference for countries with similar problems in the world.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Barton KC, Ho LC (2022) Curriculum for justice and harmony deliberation, knowledge, and action in social and civic education. Routledge, New York

Bailey PJ (1990) Reform the people: changing attitudes towards popular education in early twentieth-century China. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Bárez MM (2002) Pedagogical missions in Salamanca (1931-1936). Aula Revista Pedagogia 14:55–178. Accessed at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/41207486_Las_misiones_pedagogicas_en_Salamanca_1931-1936

Chen X, Fu QQ (1994) Fu bao chen jiao yu lun zhu xuan=Selected Works of Fu Baochen on Education. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Civera A (2013) Entre el corporativismo estatal y la redención de los pobres: los normalistas rurales en México, 1921-1969=Between state corporatism and the redemption of the poor: rural normalistas in Mexico, 1921-1969. Prismas 17(2):199–205. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=387036832009

Duan JF (2005) Wo guo da xue she hui fu wu zhi neng de li shi kao cha=A Historical Review and Study on Social Service as one of the Functions in Chinese Universities. Master Thesis, Tsinghua University, Beijing

Gao Y (1936) Jiang su sheng li min zhong jiao yu shi jian gong zuo bao gao=Report on the Experiment Work of Popular Education in Jiangsu Province. Zhong hua shu ju, Shanghai

Gao PS (1991a) Cai yuan pei jiao yu lun zhu xuan=Selected Works of Cai Yuanpei on Education. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Gao PS (1991b) Cai yuan pei jiao yu lun zhu xuan=Selected Works of Cai Yuanpei on Education. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Giroux HA, Penna AN (2012) Social education in the classroom: the dynamics of the hidden curriculum. Theory Res Soc Educ 40(7):22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.1979.10506048

Gulová L, Střelec S (2017) Social education and social work as an inspirational resource of teacher training. Czech-Pol Hist Pedagog J 9(2):21–30. https://doi.org/10.5817/cphpj-2017-0010

Hayford CW (1990) To the People-James Yen and Village China. Columbia University Press, New York

Kutschera PC, Tesoro EC, Legamia Jr BP, Sandico MG (2019) A case for integration of the North American Rural Social Work Education Model for Philippine Praxis. Paper presented at Pampanga Research Educators Organization (PREO) International Research Conference, Luzon, Philippines, 24–26 May 2019. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED595044.pdf

Liang ZY (1994) Bi jiao ri ben she hui jiao yu=Contemporary Japanese Social Education. Shan xi jiao yu chu ban she, Taiyuan

Lu H (1933) Fu xing nong cun yu tui xing xiang cun min jiao=Reviving the Countryside and Promoting Rural Education in Villagers. In: Pop Educ M-on. Available via DIALOG. http://read.nlc.cn/OutOpenBook/OpenObjectBook?aid=404&bid=93104.0. Accessed 10 Jul 1933

Lutz JG (1987) Zhong guo jiao hui da xue shi=China and the Christian Colleges, 1850-1950. Zhe jiang jiao yu chu ban she, Hangzhou

Mao ZY, Tang XC (1992) Yu qing tang jiao yu lun zhu xuan=Selected Works of Yu Qingtang on Education. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Naren GW, Xiang JF (2022) Yuan qi yu zhi gui: she hui jiao yu shi jian fazhan de zhi xu luo ji=Origin and purport: the order logic of the social educational practice development. Lifelong educ res 33(01):47–54. https://doi.org/10.13425/j.cnki.jjou.2022.01.007

Neumann R (2017) American democracy in distress: the failure of social education. J Soc Sci Educ 16(1):5–16. https://doi.org/10.2390/jsse-v16-i1-1630

Noell JF, Pallisera M, Tesouro M, Castro M (2009) Professional placement and professional recognition of social education graduates in Spain. A 10-year balance. Soc Work Educ 28(4):336–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470802243103

Northwest Normal University History Research Group (2014) Guo li xi bei shi fan da xue nong cun she hui jiao yu qu di san shi xue nian bao gao=National Northwestern Normal University Rural Social Education District Report for the 30th academic year. In: Guo li xi bei shi fan xue yuan li shi zhai lu=Extracts from the History of the National Northwest Normal College (1937-1949). Zhong guo wen shi chu ban she, Beijing

Pallisera M, Fullana J, Palaudarias JM, Badosa M (2013) Personal and professional development (or use of self) in social educator training-an experience based on reflective Learning. Soc Work Educ 32(5):576–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.701278

Pepper S (1996) Radicalism and education reform in 20th-century China: the search for an ideal development model. Cambridge University Press, New York

Real Decreto 1420/1991 (1991) de 30 de agosto, por el que se establece el título universitario oficial de Diplomado en Educación Social y las directrices generales propias de los planes de estudios conducentes a la obtención de aquél.Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 243, de 14 de dicjembre 1991, p. 32891. https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/1991/10/10/pdfs/A32891-32892.pdf. Accessed 10 Oct 1991

Shao XF (2020) Er shi shi ji yi lai zhong guo liang ci she hui jiao yu shi yan gao chao: hui gu, fan si yu zhan wang=Two Climax of Social Education Experiment in China since the 20th Century: Retrospection, Reflection, and Prospect. Lifelong educ res 31(06):51–60. https://doi.org/10.13425/j.cnki.jjou.2020.06.007

Wang DH, Wang F (1992) She hui jiao yu xue gai lun=Introduction to Social Pedagogy. Jiao yu ke xue chu ban she, Beijing

Wang L (2003) Zhong guo jin dai she hui jiao yu shi=History of Social Education in Modern China. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Wang L (2020) Xin zhong guo 70 nian wo guo she hui jiao yu zheng ce huiwang, yan jing yu qian xing=The Histories, Changes and Prospects of Chinese Social Education Policies in the Past 70 Years Since Founding of PRC. J Shaanxi Norm Univ (Philos Soc Sci Ed) 49(03):161–169. https://doi.org/10.15983/j.cnki.sxss.2020.0532

Wang L (2013) Da xue she hui jiao yu yan jiu ji yu da xue fu wu she hui de li shi kao cha=Research on University Social Education-Based on the Historical Investigation of University Serving Society. Ren min jiao yu chu ban she, Beijing

Wang XX (2021) Tao xing zhi “chuang zao de she hui jiao yu” si xiang ji qi dui gou jian zhong shen xue xi ti xi de qi shi: ji nian tao xing zhi xian sheng dan chen 130 zhou nian=The Inspiration of Tao Xingzhi’s “Creative Social Education” to the Construction of Lifelong Learning System: Commemorating the 130th Anniversary of Tao Xingzhi’s Birth. Educ Hist Stud 3(02):118–125. https://doi.org/10.19876/j.cnki.jysyj.2021.02.011

Xiong YZ (2011) Xi xue dong jiao yu wan qing she hui=The dissemination of western learning and the late Qing society. Zhong guo ren min da xue chu ban she, Beijing

Xu SL (1931) Yi ge shi zheng diao cha de chang shi=An attempt at a town survey. Sociol Circl 5:1–10. https://www.doc88.com/p-60373908418184.html

Xu SL (1933) Qing he xiang cun she hui zhong xin=Ching Ho Rural Social Centre. Heb Mon 2:1–13

Yenching University Rural Work Seminar (1934) Nong cun jian she shi yan=Rural Construction Experiment. Zhong hua shu ju, Shanghai

Zhang HB (2008) Lun da xue de she hui jiao yu gong neng=On the socio-educational function of universities. Master Thesis, Shanxi University, Taiyuan

Zhang AF, Dong FP (2005) Xian dai da xue de she hui fu wu zhi neng=The Social Service Function of Modern Universities. High Educ Dev Eval 21:25–27

Zheng YF (1936a) Guo li zhong shan da xue xiang cun fu wu shi yan qu (1)=National Sun Yat-sen University rural service experimental area report (1). Guo li Sun Yat-sen da xue chu ban she, Guangzhou. Accessed at: https://www.doc88.com/p-50616107397636.html

Zheng YF (1936b) Guo li zhong shan da xue xiang cun fu wu shi yan qu (2)=National Sun-Yat sen University rural service experimental area report(2). Guo li Sun Yat-sen da xue chu ban she, Guangzhou. Accessed at: https://taiwanebook.ncl.edu.tw/zh-tw/book/NTUL-9910001912/reader

Zhou DZ (1933) Shi shi min jiao ying cong he chu xia shou=Where to start with the implementation of popular education. Pop Educ Mon 1:1, http://read.nlc.cn/OutOpenBook/OpenObjectBook?aid=404&bid=93104.0

Zhu GJ, Wang SM (2007) Shi lun min guo shi qi min zhong jiao yu de shi jian yi bei xia shi yan qu wei li=Discussion on the Practice of Popular Education in the Republic of China-Taking the Beixia Experimental Area as an Example. J Nanjing Agric U (Soc Sci Ed) 4:85–90

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Post-grant funding of the Chinese National Social Science Foundation (Grant No. 20FJKB003). The authors would like to thank Dr. Qi Wang of Beijing Foreign Studies University and Dr. Zhenzhen He of Beijing Union University for their kind assistance in the revision of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XW contributed to the conception of the study and wrote the manuscript. JL helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions and manuscript preparation and revisions. XW and JL contributed equally to this work and should be regarded as co-first authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors. This article uses mainly the case study method and the historical documentary research method. Our case subjects are universities; as such, experimental data and biological materials are not involved in the analysis of the cases, and none of the historical documents we have cited deal with ethical issues. Therefore, this study does not need to obtain ethical approval.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Liu, J. Chinese universities’ experience of social education, 1912–1949. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 346 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01366-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01366-3