Abstract

Gender-affirming hormones have been shown to improve psychological functioning and quality of life among transgender and nonbinary (trans) people, yet, scant research exists regarding whether and why individuals take more or less hormones than prescribed. Drawing on survey data from 379 trans people who were prescribed hormones, we utilized multivariable logistic regression models to identify factors associated with hormone-dosing behaviors and content analysis to examine the reasons for dose modifications. Overall, 24% of trans individuals took more hormones than prescribed and 57% took less. Taking more hormones than prescribed was significantly associated with having the same provider for primary and gender-affirming care and gender-based discrimination. Income and insurance coverage barriers were significantly associated with taking less hormones than prescribed. Differences by gender identity were also observed. Addressing barriers to hormone access and cost could help to ensure safe hormone-dosing behaviors and the achievement trans people’s gender-affirmation goals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Access to gender-affirming hormones is crucial to many transgender and nonbinary (trans) individuals’ mental health and well-being. While not all trans individuals will seek out hormones, access to and use of hormones can be life-changing among those who do, particularly those with gender dysphoria. Individuals with gender dysphoria experience distress related to differences between their sex assigned at birth and gender identity (Ashley, 2021) and may experience episodes of distress, ruminative thinking, anxiety, and depression (Bouman et al., 2017; Chodzen et al., 2019; Klemmer et al., 2021; Silva et al., 2021). As gender-affirming hormones are highly effective in developing secondary sex characteristics and are less costly and more accessible than gender-affirming surgeries, hormones are most often the first or only form of gender-affirming care trans patients will seek out (Restar et al., 2019; White Hughto & Reisner, 2016). Notably, hormone use has been shown to significantly improve psychological functioning and quality of life, reduce suicidal attempts and ideations, promote body satisfaction, and decrease gender dysphoria and is therefore considered medically necessary for many trans people (Bouman et al., 2017; Foster Skewis et al., 2021; Herman et al., 2019; Klemmer et al., 2021; White Hughto & Reisner, 2016).

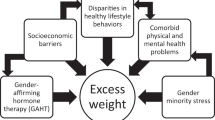

Notably, there are several major barriers to accessing hormones and other forms of gender-affirming care, including systemic issues such as lack of insurance coverage, lack of availability of competent providers who prescribe hormones, and interpersonal-level experiences of bias and discrimination (James et al., 2021; Lerner et al., 2021; Puckett et al., 2018; Sperber et al., 2005). Many studies also find that trans people experience financial barriers to accessing hormones due in part to the fact that trans people are less likely than cisgender people to have health insurance (Lerner et al., 2021) and many insurance plans do not cover the cost of gender-affirming medical interventions (James et al., 2021; Lerner et al., 2021), despite the fact that gender-affirming care is a cost-effective intervention (Baker, 2017). Discrimination and mistreatment in clinical encounters also present barriers to accessing hormones, such as providers asking invasive questions, refusing care, verbally harassing or using abusive language, and physically abusing trans patients (Hoffkling et al., 2017; Lerner et al., 2021; Redfern & Sinclair, 2014; Sperber et al., 2005). Even when providers do not explicitly discriminate or mistreat their trans patients, they often decline or refuse to provide adequate care for this population due to transphobia, lack of clinical and cultural competency, or both (Hughto et al., 2015; Lerner et al., 2021). Lack of education on how to care for and interact with trans patients creates negative interactions between patients and providers, which can lead to future avoidance of care and medical mistrust on the part of trans people (Hughto et al., 2015; Johnson et al., 2020; Lerner et al., 2021).

The use of gender-affirming hormones in a manner that is inconsistent with prescribed dosages can have adverse clinical and health consequences (Webb et al., 2020). Research on general medication adherence has shown that many factors influence an individual’s decision and ability to follow a prescribed treatment plan. Indeed, economic barriers, convenience, and poor communication with prescribing physicians have been shown to influence whether an individual will take medication as prescribed (Ratanawongsa et al., 2013; Sabaté & Sabaté, 2003; Zolnierek & DiMatteo, 2009). However, to our research team’s knowledge, there are currently no studies that detail why some individuals do not take hormones as prescribed. To fill this gap, the primary objective of this exploratory study is to identify the sociodemographic, healthcare indicators, and discrimination experiences associated with taking more or less hormones than prescribed, as well as trans people’s reasons for modifying their prescribed dose.

Methods

Study sample and procedures

This is a secondary cross-sectional analysis of survey data from Project VOICE (Voicing Our Individual and Community Experiences), a needs assessment led by the Fenway Institute at Fenway Health (Fenway) and the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition (MTPC). Between March and August 2019, trans residents of Massachusetts (MA) and Rhode Island (RI) were surveyed about their sociodemographics, healthcare experiences, and health. Respondents were purposively sampled and recruited via venues where trans people congregate, including online sites such as listservs and community-based social networking webpages, as well as in-person sites such as trans-specific community events and trans-friendly clinics. Participants were eligible for the study if they were 18 years or older, self-identified as transgender or nonbinary, resided in MA or RI, were willing to provide electronic written informed consent, and spoke either English or Spanish. Eligible respondents who completed the survey were invited to opt into a community raffle for one of 54 gift cards, with values ranging from $10 to $250. Additional details on the study procedures can be found elsewhere (Restar et al., 2020).

The present analysis focuses on a subsample of 379 trans respondents who indicated that they were currently taking hormones as part of their gender-affirmation care. This secondary analysis aimed to identify characteristics of trans respondents who reported taking more hormones than prescribed and respondents who reported taking less hormones than prescribed and to descriptively detail reasons for these modifying their hormone-dosing behaviors.

Measures

Sociodemographic

Respondent’s age was assessed in years and recoded as young adult (age 18–29) vs. all others (age 30+). Race/ethnicity was asked as a check-all-that-apply question and combined into White (non-Hispanic) vs. People of Color (POC, including Asian/Pacific Islander, Black, Hispanic/Latino, another race, and multiple races/ethnicities). Following the best-practice two-step method to assess gender (Reisner et al., 2016), we combined two items on assigned sex at birth (female, male) and current gender identity to denote respondents who are transfeminine, transmasculine, or nonbinary (e.g., genderqueer, gender non-conforming). Respondents were then asked if they were currently employed for wages or not. Lastly, low income was recoded if personal income fell below $30,000 (vs. not).

Healthcare experiences and discrimination

A series of questions about health insurance, routine care, and gender-affirming care were asked. First, health insurance coverage for hormones was recoded to “yes” if it was covered, vs. “no” if it was not covered or the patient had no insurance. Respondents were then asked if they go to the same provider for both primary and gender-affirming care, with response options as either “yes, I go to the same provider for both types of care” or “no, I see a different provider for each type of care.” Respondents were asked in years when they received routine care last, and responses were dichotomized as “yes” if care was received within the past year vs. “no.” Similarly, mental health treatment within the past year was dichotomized as yes/no.

A series of questions about past year routine care avoidance were asked. Respondents indicated “yes” if, within the past year, they have postponed or did not try to get check-ups or other preventative medical care because of (a) gender-based mistreatment, (b) not being able to afford care, or (c) a doctor or other provider refused to treat them.

To assess major gender-based discrimination experiences, respondents were asked whether, in the past year, they had experienced the following because of their gender identity: (a) discouraged by a teacher or advisor from seeking higher education, (b) denied a scholarship, (c) not hired for a job (d) not given a promotion, (e) fired, (f) prevented from renting or buying a home in the neighborhood you wanted, (g) prevented from remaining in a neighborhood because neighbors made life so uncomfortable, (h) hassled by the police, (i) denied a bank loan, (j) provided inferior service by a store/restaurant employee, plumber, mechanic, or service provider, (k) denied medical care. Responses were coded as “1” if yes or “0” if no and were summed to create a continuous score of major gender-based discrimination experiences (range: 0–11).

Hormone therapy dosing behaviors (outcome)

Hormone-dosing behaviors were assessed via two questions that asked respondents [1] how often they take more hormones than prescribed; and [2] how often they take less hormones than prescribed. The questionnaire provided the following definition: “taking what is prescribed means taking the right dose at the time as instructed by a healthcare provider.” Response options for both questions ranged from never to always and were recoded as yes (rarely, sometimes, most of the time, always) vs. no (never).

In a check-all-that-apply question design, respondents who reported taking more or less hormones than prescribed were asked to provide detailed information about why they took their hormones other than as prescribed. For those who indicated that they were taking more hormones than prescribed, potential reasons included the following: (a) I think that taking more hormones will speed up my transition/gender-affirmation process, (b) my friends suggested I should take more, (c) I don’t trust my doctor/healthcare provider’s advice, (d) I do not think my doctor/healthcare provider is giving me the right dose, (e) My hormones make me feel good, or (f) Other, please specify. Similarly, for those who indicated that they were taking less hormones than prescribed, potential reasons included the following: (a) I cannot afford it, (b) I have no health insurance, (c) I forget to take it, (d) I forget to pick up my prescription, (c) I get it through friends, online, or on the street, and it’s not always available, (d) I do not trust my doctor/healthcare provider’s advice, (e) I do not think my doctor/healthcare provider is giving me the right dose, (f) It is hard for me to get to my doctor’s appointment to get the prescription, (g) My doctor/healthcare provider said I didn’t need to take it, (f) I am afraid my hormones will not work well with the other medications I take, (g) I am worried about gaining weight, (h) My hormones make me feel sick, (i) I am not sure I want to take hormones anymore, (j) Other, please specify. Response options to these questions were based on feedback from community partners and medical providers as key informants involved in the survey design.

Data analysis

Univariate descriptive statistics [mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency, and proportions] were performed to examine the overall distribution of the final analytical sample, overall (n = 379) and stratified by the two hormone-dosing questions. We also used bivariate analyses to examine patterns of hormone-dosing behaviors based on respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics, healthcare experiences, and discrimination.

Next, we performed a multivariable analysis using logistic regression to assess relationships between the independent variables (i.e., sociodemographic, healthcare experiences, and discrimination) and our main outcome (i.e., took more hormones than prescribed, took less hormones than prescribed. We then constructed two separate multivariable regression models, one for each outcome. Given the exploratory nature of this study, prior to building our models, we utilized a lasso procedure to select key variables to include in the model (Tibshirani, 1996). Given our modest sample size, we used nonparametric bootstrapping with 1000 iterations to estimate confidence intervals and reduce Type 1 error per model (Parra‐Frutos, 2014). The significance level was set to p < 0.05 a priori. We used Stata-MP version 17.0 to perform all statistical analyses.

Finally, we calculated the frequency of each reason for taking more or less hormones. We then utilized content analysis to examine the write-in responses under the category “other” (Kohlbacher, 2006). Each emergent theme was descriptively analyzed and included in the final list of reasons.

Ethics

All enrolled respondents provided their electronic, written informed consent, which detailed the voluntary nature of their participation and their rights to confidentiality and privacy. All study activities were approved by the Fenway Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results

Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are shown in Table 1. About half of the respondents were young adults under the age of 30 (51%). The majority of respondents were White non-Hispanic (82%). A third of participants (33%) were transfeminine, 44% transmasculine, and 23% nonbinary. More than half of the sample was employed for wages (70%), and more than half reported having a low income (53%).

The majority of the sample reported having health insurance that covers hormones (85%), having the same provider for primary and gender-affirming care (74%), and receiving routine care in the past year (83%). A third received mental health treatment in the past year (37%). A total of 19% reported avoiding routine care in the past year due to gender-based mistreatment, and 26% avoided care due to cost. A total of 6% reported experiencing having a provider who refused them treatment in the past year. The mean number of major gender-based discrimination experiences in the past year was 1.7 out of a possible 11 (standard deviation [SD] = 1.9).

Overall, 24% of the sample reported taking more hormones than prescribed, and 57% reported taking less hormones than prescribed at some point in their lives. Less than one-fifth (19%) did not report modifying their hormone dosage. Among those who took more hormones than prescribed (n = 90), 44.4% were transfeminine, 33.3% were transmasculine, and 22.2% were nonbinary respondents. Among those who took less hormones than prescribed (n = 215), 27% were transfeminine, 46% were transmasculine, and 27% were nonbinary respondents.

Regression outcome: taking more hormones than prescribed

Table 2 shows the adjusted multivariable logistic regression models examining factors associated with taking more hormones than prescribed. In the final model, the odds of taking more hormones were lower among respondents who identified as transmasculine compared to transfeminine (adjusted OR [aOR]=0.45, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] = 0.23–0.88) and among low-income respondents (aOR = 0.41, 95% CI = 0.20–0.82). The odds of taking more hormones than prescribed were higher among respondents who reported having the same provider for primary and gender-affirming care (aOR = 2.14, 95% CI = 1.04–4.44) and those with an increased number of major gender-based discrimination experiences out of a possible 11 (aOR = 1.25 per experience, 95% CI = 1.08–1.44).

Regression outcome: taking less hormones than prescribed

Table 2 also shows the adjusted multivariable logistic regression models examining factors associated with taking less hormones than prescribed. In the final model, the odds of taking less hormones than prescribed were higher among nonbinary respondents compared to transfeminine respondents (aOR = 2.06, 95% CI = 1.05–4.04), those with a low income (aOR = 1.94, 95% CI = 1.13–3.32), those with no insurance coverage for hormones (aOR = 4.27, 95% CI = 1.73–10.56), and those who had received mental health treatment in the past year (aOR = 2.00, 95% CI = 1.14–3.48).

Reasons for taking more hormones

As shown in Table 3, the most endorsed reasons for taking more hormones than prescribed were believing that it is not the right prescribed dose (37%), taking it to feel good (36%), to speed up transition or the gender-affirmation process (27%), and making up for missed doses (17%).

Emergent themes from the write-in responses included the following reasons for taking more hormones: making up for missed doses, having concerns about reproductive health, and having an imprecise practice of dose administration.

Many respondents reported making up for missed hormone doses as a reason for taking more hormones than prescribed, with some respondents indicating “doubling” or taking “a little extra” dose if missed. These respondents noted:

“If I miss a week because my pharmacy took forever to get my T (testosterone) in, I’ll sometimes go to 0.45 on the 1 mL syringe instead of 0.4.” (transmasculine respondent, age 24)

“Accidentally doubling my dose because I forgot that I took the first.” (transfeminine respondent, age 37)

“I miss my shot day; I accidentally pull a little extra when getting the shot ready.” (nonbinary respondent, age 29)

Reproductive health concerns regarding menstruation also emerged as one of the reasons transmasculine people reported taking more hormones than prescribed. Specifically, many transmasculine respondents reported taking higher doses of their hormones to mitigate one’s gender dysphoria and physical discomfort related to menstruation. Participants noted:

“Experience menstrual cramping.” (transmasculine respondent, age 45)

“If I start bleeding.” (transmasculine respondent, age 29)

“Period returned making me feel dysphoric.” (transmasculine respondent, age 28).

Lastly, some respondents noted that taking more hormones than prescribed also occurred when they experienced logistical difficulty self-administering hormones via injection, as preparing the dose can sometimes lead to “imprecise” measurement. Specifically, respondents mentioned that they often increase their dose as it is “easier to go over than try to be exact” or compensate for when the medication “leaks” out of the syringe, as described below:

“I take a bit more most times because some usually leaks out.” (transmasculine respondent, age 19).

“Measurement is imprecise and I honestly don’t care about getting it perfect—easier to go over than try to be exact.” (transmasculine respondent, age 37)

Reasons for taking less hormones

As shown in Table 3, the most commonly endorsed reasons for taking less hormones than prescribed were forgetting to take the medication (70%), forgetting to pick up the prescription (27%), cost of hormones (18%), experiencing transportation barriers when attempting to pick up their prescription (13%), having syringe concerns (e.g., phobia, pain, anxiety) (9%), health insurance issues (e.g., lack of insurance, delay in approval, changes in in-network provider) (7%), and believing that the prescribed dose was incorrect (5%).

Among those who indicated taking less hormones than prescribed, emergent themes included experiencing other physical concerns (e.g., hair loss, acne issues), pharmacy issues (e.g., delays or unavailability of refills, being stigmatized by the pharmacist), and reliance on other people to administer their hormones.

Some participants who endorsed taking less hormones than prescribed reported experiencing psychological and physical concerns about using syringes, particularly pain at the injection site, as well as anxiety and phobia related to the injection. These negative experiences and concerns with syringes could deter some participants from successfully taking their medication, as described by the following respondents:

“Intense anxiety about injecting prevents me from completing a shot.” (nonbinary age 20)

“Injection method is uncomfortable.” (transmasculine, age 26)

“Injection site pain/fatigue.” (transmasculine, age 32)

“The injections are painful, so I often procrastinate on it.” (transmasculine, age 39)

Moreover, experiencing pain from injecting could also delay the timing of hormone administration. For instance, one respondent who reported taking less hormones than prescribed elaborated on how they would adjust the frequency of taking their hormones by 5 or more days to mitigate injection pain. They noted:

“I use IM (intramuscular) injections for hormones; it is painful to use needles, so rather than every 7 days as prescribed, I do once every 12 days.” (transmasculine, age 33)

Another reason some respondents endorsed taking less hormones than prescribed is to mitigate the physical side effects of hormones. For instance, one nonbinary respondent described experiencing hair loss, and one transmasculine respondent reported experiencing acne, which would, in turn, led them to reduce their hormone dose to mitigate these side effects, as described below:

“It causes lots of hair loss so I just dab it on to feel good, but the regular application makes my hair fall out more.” (nonbinary, age 36)

“To reduce acne issues.” (transmasculine, age 29)

Additionally, one nonbinary respondent, while “liking all other effects” of testosterone, described developing distress associated with body hair grow and lowered their dose to minimize these physical changes:

“Dysphoria from body hair growth caused by T (testosterone), despite liking all the other effects.” (nonbinary, age 29)

Some respondents described prescription fill-related barriers as a reason for taking less hormones than prescribed. These barriers ranged from prescription unavailability and refill delays to forgetting to call in refills, which made some respondents ration their hormones. As the following three respondents expressed:

“Pharmacy has hard time acquiring medication.” (transmasculine, age 43)

“I’m afraid of running out/losing access to hormones and want to have a backup supply, or sometimes I forget to call in refills in time and have to stretch what I have left so I’m not off hormones cold turkey while I wait to get more.” (transfeminine, age 26)

“Very afraid of running out and not being able to get more. It’s all I have left.” (transfeminine, age 38)

Additionally, some participants reported experiencing gender-based discrimination by pharmacists when picking up their hormone prescriptions, which discouraged them from coming into the pharmacy again or caused them to delay or not obtain their hormones. This was noted by the following two respondents:

“It’s a restricted substance and the pharmacy always gives me grief trying to pick it up. It’s the only prescription I have [in which] pharmacists are weird with me about or call up my doctor for, and I’ve never had that happen even with other controlled substances.” (transmasculine, age 19)

“Discrimination faced at pharmacies filling orders.” (transmasculine, age 23)

Lastly, one respondent noted that they take less hormones than prescribed due to having to rely on others to administer their dose. This respondent noted,

I can’t administer it myself and have to rely on others. (transmasculine, age 24)

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to descriptively explore and detail dosing behaviors of prescribed hormones among trans populations. Taken together, our results indicate that access barriers related to income and insurance coverage were associated with trans respondents taking less hormones than prescribed whereas taking more hormones than prescribed was associated with having one’s primary care physician also prescribe hormone treatment, as well as with experiences of gender-based discrimination. While exploratory, these findings show a critical need for examining ways to optimize adherence to gender-affirming hormones by addressing multiple levels of individual and structural barriers that can deter trans people from meeting their gender-affirmation goals.

We found that participants were more likely to take less hormones than prescribed due to a range of factors reflecting both structural barriers to access and perceived incentives to take a reduced dose. Insurance issues were a major contributor to variable dosing: specifically, a lack of insurance coverage, whether due to being uninsured or having health insurance that did not cover hormones, was highly associated with taking a reduced dose, potentially due to rationing or the inability to consistently afford the cost of their hormone prescription with no insurance coverage. A prior study found that uninsured trans people were less likely to be on any hormone treatment than insured trans people (Stroumsa et al., 2020). Even for people with insurance coverage, exclusions of gender-affirming care, including hormone therapy, persist among people with public insurance (particularly state Medicaid programs) and people with private insurance plans (Dowshen et al., 2019; Kirkland et al., 2021; Zaliznyak et al., 2021). Similarly, while the literature on distance traveled to access gender-affirming services like hormones is scant, existing research illustrates a willingness to travel further distances to access knowledgeable providers that are capable of providing gender-affirming healthcare (Cicero et al., 2019; Kattari et al., 2020). While online prescribers are growing and expanding access to more areas, state-level policies on insurance, combined with controlled substance regulations, continue to vary state-by-state; thus access to online prescribers of gender-affirming hormones may be limited for trans people in certain geographic areas (Baker, 2017; Beauchamp, 2013; Holt et al., 2019; Kattari et al., 2020). Our findings related to insurance coverage, regulations, and provider availability suggest that, while some trans people in our study are able to access hormones, they may not be able to take the prescribed dose consistently. Cost issues may be driving hormone access issues as having a low-income was associated with taking hormones at lower doses than prescribed. Even with insurance coverage, individuals who have lower incomes may still be unable to consistently afford the co-pay for their hormone prescription and so they may reduce their hormone dosage as a way to ration their medication between refill cycles. These findings are important given previous research highlighting that trans people, despite having on average higher educational attainment than cisgender people, tend to have reduced employment and reduced income compared to the general population (Adams & Vincent, 2019; Seelman et al., 2017). To improve access to hormone treatment, both the availability and quality of insurance coverage, including overall insurance and medication affordability and specific provisions for the coverage of gender-affirming hormone therapy, should be improved in states across the country.

Receiving mental health treatment was also associated with reduced hormone use, though it is not clear whether this reflects a causal relationship or merely a co-occurring phenomenon. For instance, individuals receiving mental health treatment may do so because they struggle with daily functioning, including the functioning needed to receive and take hormones consistently. The challenge of taking hormones consistently is somewhat supported by the fact that forgetting to take hormones was the most commonly reported reason for missing a hormone dose. Prior studies have shown that non-attendance and non-adherence to physical health visits and medication are associated with poor mental health (Kretchy et al., 2014; Marrero et al., 2020). Receiving hormones has been associated with better mental health outcomes among trans people, including reduced depression and anxiety and improved quality of life (Baker et al., 2021; White Hughto & Reisner, 2016). However, other barriers and burdens may be associated with more severe mental health disorders that require treatment that may impact hormone use. Regardless of potential confounding, there should also be greater provider education about the particular barriers and gender-affirmation goals of nonbinary people seeking hormones.

We also found several associations with taking more hormones than prescribed. In particular, having the same healthcare provider for primary and gender-affirming care was associated with individuals taking doses beyond what was prescribed. From the write-in responses, overdosing and underdosing were both reported among those who mistrust their provider. In previous studies of trans people’s experiences in primary healthcare, one study found that 53.6% of trans participants reported that their primary care provider did not know enough about trans people to provide adequate care (Heng et al., 2018). Additionally, multiple studies reported that trans patients were educating their providers and conducting their own research (Costa et al., 2018; Dewey, 2008; Roller et al., 2015). Therefore, respondents may perceive that a primary care physician lacks the specialization to make informed dosage decisions and take dosing into their own hands. Our findings underscore the need for better integration of gender-affirming care with primary care, and vice versa, to optimize hormone adherence. Given differences between trans-friendly and trans-specific modes of service design and provision (Everhart et al., 2022), perspectives from trans patients regarding the ideal integration models, such as providing gender-affirming care in primary care settings vs. having primary care services in gender-affirming specialty clinics, could be helpful in understanding which models would feel more trustworthy, affirming, and likely to improve hormone adherence.

Individuals with greater reported experiences of gender-based discrimination were more likely to increase their dose beyond what was prescribed. This mechanism may be due in part to the desire to align one’s internal perceptions of one’s gender with one’s gender-affirming hormone goals. For example, individuals who are more likely to be perceived as nonbinary may experience increased gender-related discrimination (Anderson et al., 2020; Anderson, 2020; Cruz, 2014; Mizock et al., 2017), and therefore may feel compelled to take higher doses of hormones to achieve a more binary gender presentation and avoid discrimination. Future research should examine the reasons why individuals take higher hormone doses than prescribed, including the specific roles that discrimination and gender dysphoria play in trans people’s decisions around increased hormone dosing, particularly given that some trans people may not want to conform to binary gender expectations. It is also paramount that stigma and transphobia be addressed to reduce discrimination and support trans people’s health and well-being.

There were also gender-based differences in respondents reporting of taking more or less hormones than prescribed. Indeed, transmasculine respondents had reduced odds of taking more hormones than prescribed compared to transfeminine respondents. There are several potential mechanisms that may explain these findings, including that testosterone is highly regulated as a controlled substance, adding more structural barriers for providers, pharmacists, and trans people. Additionally, this finding might also be due to the prominence of secondary sex characteristics and perceived negative side effects of taking more testosterone compared to estrogen. For transfeminine people who begin hormones post-puberty, secondary sex characteristics may be perceived as more pronounced. Therefore, there may be a greater need to take increased doses to see intended results compared to transmasculine people, who may be likely to see quicker changes in their secondary sex characteristics at the prescribed dose. Additionally, while both estrogen and testosterone may yield unwanted side effects (Getahun et al., 2018; T’Sjoen et al., 2019), testosterone may be associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing unwanted effects, such as increased acne (Motosko et al., 2019), concerns around mood and aggression (Kristensen et al., 2021), and concerns that higher levels of testosterone will convert to estrogen and not produce the desired treatment effect. Although many of these concerns have been documented among people on testosterone there is a lack of empirical evidence to support many of these claims. For example, one large study found no association between serum testosterone levels and acne prevalence among transmasculine people, though age at the start of hormones was a risk factor for acne (Thoreson et al., 2021). Other studies have shown mixed evidence of changes in anger following testosterone therapy, with none following up longer than the first years on treatment (Defreyne et al., 2019; Kristensen et al., 2021; Motta et al., 2018; Thoreson et al., 2021). Further, while estradiol conversion is largely understudied among transmasculine participants, one small study from Massachusetts found estradiol levels decreased with testosterone treatment, with no evidence of conversion to estrogen greater than that in cisgender men (Chan et al., 2018). Nonetheless, concerns around unwanted side effects persist among some trans patients on hormone therapy, likely reflecting individual clinical histories and personal and community perceptions, rather than large-scale negative side effects across the population.

We also found that identifying as nonbinary, compared to identifying as transfeminine, was associated with using a lower dose of hormones than prescribed. This gender difference may be related to the specific treatment goals of nonbinary people, which may differ from binary trans people. The lower use of hormones by nonbinary people may suggest a need for prescribers to communicate better with nonbinary patients about their gender-affirmation goals. Notably, there is a paucity of studies on nonbinary people’s health in general (Matsuno & Budge, 2017; Scandurra et al., 2019), and no studies to our knowledge have examined the specific motivations and desires of nonbinary people compared to binary trans people in their gender-affirming care. While recent articles have made a case for tailoring hormone regimens to the needs of individual nonbinary patients (D’hoore & T’Sjoen, 2022; T’Sjoen et al., 2019), providers may hesitate to tailor hormone doses due to a lack of expertize in identifying and maintaining tailored regimens. Given recent research suggesting that nonbinary people more frequently have to educate their providers about the needs of trans people than binary trans people (Reisner & Hughto, 2019), it is possible that nonbinary people are not being prescribed hormone doses that meet their gender-affirmation goals and therefore feel compelled to tailor their dosage themselves. Future research into intra-transgender community priorities and concerns around hormone use is important to fully understand gender differences in how trans people take their prescribed hormones. Moreover, as this study did not ascertain specific gender-affirming hormones (e.g., estrogen vs. testosterone), understanding which hormones were being prescribed and used among nonbinary people would be important to understanding and contextualizing how to best address the needs of this group.

Lastly, while our sample did not reflect concordant reporting of taking more and less hormones than prescribed, it is conceptually possible that individuals may take more and less hormones at different times—a potential point for future research investigation. The timing and circumstances of when modified dosing behaviors occur should be explored in future longitudinal, mixed-methods studies (e.g., ecological momentary assessments). Findings from such studies could be used to identify strategies to promote adherence and maintenance of hormone use among trans populations.

Limitations

This study has methodological limitations that should be considered when interpreting findings. As a cross-sectional study, causality cannot be determined. Moreover, given the use of convenience sampling and the web-based survey, it is possible that the final sample is not representative of the entire trans population, including those who do not have access to the internet. Additionally, the measures used here are based on self-report, which is subject to bias. Although the racial/ethnic composition of the sample reflected that of the Massachusetts and Rhode Island populations (U.S. Census, 2020a, 2020b), results from this study are not generalizable to all trans people in the US, particularly communities largely comprised of racial/ethnic minority populations. Additionally, although we oversampled communities of color and recognized the heterogeneity of racial/ethnic minority communities, due to the lower percentage of participants from each racial/ethnic minority group, we had to combine all non-White participants as a single group (i.e., people of color). This analytical approach may have masked important differences in hormone usage by race/ethnicity. Ethnoracial identity in the context of healthcare provision and access is best used as a proxy for identifying individuals exposed to systemic racism (Lett et al., 2022). Future studies of adherence should capture a more ethnoracially diverse cohort and include direct measures of systemic racism and discrimination to understand if and how hormone regimen adherence may vary due to the noxious exposure to racism (Lett et al., 2022).

Conclusions

In sum, the present study found the majority of trans individuals surveyed had used hormones at a lower or higher dose than prescribed. Trans individuals who take hormones at doses different than what was prescribed may choose to modify their dose as a means of achieving their gender-affirmation goals, mitigating the adverse physical side effects of hormones, and enhancing physiological and psychological effects of hormones. Structural and interpersonal barriers to care, including cost, lack of insurance coverage, and discrimination, were also found to be key drivers of taking hormones differently than prescribed. These findings underscore the need to eliminate barriers to taking medically necessary hormones for trans populations and the importance of providers understanding the gender-affirmation goals of their trans patients so that they can prescribe appropriate hormone regimens. Future research should seek to understand how providers determine hormone dosing and communicate safety messages to ensure that trans patients are able to achieve their gender-affirmation goals safely and effectively.

Data availability

Given that this study contains data with potentially sensitive information, data from this study are available upon request. Contact the The Fenway Institutional Review Board (IRB) Committee (information@fenwayhealth.org) for data requests.

Change history

21 October 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01386-z

References

Adams NJ, Vincent B (2019) Suicidal thoughts and behaviors among transgender adults in relation to education, ethnicity, and income: a systematic review. Transgender Health 4(1):226–246

Anderson AD, Irwin JA, Brown AM, Grala CL (2020) “Your picture looks the same as my picture”: an examination of passing in transgender communities. Gender Issues 37(1):44–60

Anderson SM (2020) Gender matters: the perceived role of gender expression in discrimination against cisgender and transgender LGBQ individuals. Psychol Women Q 44(3):323–341

Ashley F (2021) The misuse of gender dysphoria: toward greater conceptual clarity in transgender health. Perspect Psychol Sci 16(6):1159–1164

Baker KE (2017) The future of transgender coverage. N Engl J Med 376(19):1801–1804

Baker KE, Wilson LM, Sharma R, Dukhanin V, McArthur K, Robinson KA (2021) Hormone therapy, mental health, and quality of life among transgender people: a systematic review. J Endocrine Soc 5(4):bvab011

Beauchamp T (2013) The substance of borders: transgender politics, mobility, and US state regulation of testosterone. GLQ J Lesbian Gay Stud 19(1):57–78

Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, Crawford JR, Millet N, Fernandez-Aranda F, Arcelus J (2017) Transgender and anxiety: a comparative study between transgender people and the general population. Int J Transgenderism 18(1):16–26

Chan KJ, Jolly D, Liang JJ, Weinand JD, Safer JD (2018) Estrogen levels do not rise with testosterone treatment for transgender men. Endocr Pract 24(4):329–333

Chodzen G, Hidalgo MA, Chen D, Garofalo R (2019) Minority stress factors associated with depression and anxiety among transgender and gender-nonconforming youth. J Adolesc Health 64(4):467–471

Cicero EC, Reisner SL, Silva SG, Merwin EI, Humphreys JC (2019) Healthcare experiences of transgender adults: an integrated mixed research literature review. Adv Nurs Sci 42(2):123

Costa AB, da Rosa Filho HT, Pase PF, Fontanari AMV, Catelan RF, Mueller A, Cardoso D, Soll B, Schwarz K, Schneider MA (2018) Healthcare needs of and access barriers for Brazilian transgender and gender diverse people. J Immigr Minor Health 20(1):115–123

Cruz TM (2014) Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: a consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Social Sci Med 110:65–73

D’hoore L, T’Sjoen G (2022) Gender‐affirming hormone therapy: an updated literature review with an eye on the future. J Int Med 291(5):574–592

Defreyne J, Kreukels B, t’Sjoen G, Staphorsius A, Den Heijer M, Heylens G, Elaut E (2019) No correlation between serum testosterone levels and state-level anger intensity in transgender people: results from the European Network for the Investigation of Gender Incongruence. Hormone Behav 110:29–39

Dewey JM (2008) Knowledge legitimacy: how trans-patient behavior supports and challenges current medical knowledge. Qual Health Res 18(10):1345–1355

Dowshen NL, Christensen J, Gruschow SM (2019) Health insurance coverage of recommended gender-affirming health care services for transgender youth: shopping online for coverage information. Transgender Health 4(1):131–135

Everhart AR, Boska H, Sinai-Glazer H, Wilson-Yang JQ, Burke NB, LeBlanc G, Persad Y, Ortigoza E, Scheim AI, Marshall Z (2022) ‘I’m not interested in research; i’m interested in services’: how to better health and social services for transgender women living with and affected by HIV. Soc Sci Med 292:114610

Foster Skewis L, Bretherton I, Leemaqz SY, Zajac JD, Cheung AS (2021) Short-term effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on dysphoria and quality of life in transgender individuals: a prospective controlled study. Front Endocrinol 12: 717766

Getahun D, Nash R, Flanders WD, Baird TC, Becerra-Culqui TA, Cromwell L, Hunkeler E, Lash TL, Millman A, Quinn VP (2018) Cross-sex hormones and acute cardiovascular events in transgender persons: a cohort study. Ann Int Med 169(4):205–213

Heng A, Heal C, Banks J, Preston R (2018) Transgender peoples’ experiences and perspectives about general healthcare: a systematic review. Int J Transgend 19(4):359–378

Herman JL, Brown TN, Haas AP (2019) Suicide thoughts and attempts among transgender adults: findings from the 2015 US Transgender Survey. UCLA School of Williams Institute

Hoffkling A, Obedin-Maliver J, Sevelius J (2017) From erasure to opportunity: a qualitative study of the experiences of transgender men around pregnancy and recommendations for providers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(2):1–14

Holt NR, Hope DA, Mocarski R, Woodruff N (2019) First impressions online: The inclusion of transgender and gender nonconforming identities and services in mental healthcare providers’ online materials in the USA. Int J Transgend 20(1):49–62

Hughto JMW, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE (2015) Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med 147:222–231

James S, Herman J, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M (2021) The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey. Published online 2016. National Center for Transgender Equality

Johnson AH, Hill I, Beach-Ferrara J, Rogers BA, Bradford A (2020) Common barriers to healthcare for transgender people in the US Southeast. Int J Transgender Health 21(1):70–78

Kattari SK, Grange J, Seelman KL, Bakko M, Harner V (2020) Distance traveled to access knowledgeable trans-related healthcare providers. Ann LGBTQ Public Popul Health 1(2):83–95

Kirkland A, Talesh S, Perone AK (2021) Transition coverage and clarity in self-insured corporate health insurance benefit plans. Transgender Health 6(4):207–216

Klemmer CL, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF (2021) Transphobia-based violence, depression, and anxiety in transgender women: the role of body satisfaction. J Interpers Viol 36(5-6):2633–2655

Kohlbacher F (2006) The use of qualitative content analysis in case study research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum, Qualitative Social Research

Kretchy IA, Owusu-Daaku FT, Danquah SA (2014) Mental health in hypertension: assessing symptoms of anxiety, depression and stress on anti-hypertensive medication adherence. Int J Mental Health Syst 8(1):1–6

Kristensen TT, Christensen LL, Frystyk J, Glintborg D, T’sjoen G, Roessler KK, Andersen MS (2021) Effects of testosterone therapy on constructs related to aggression in transgender men: a systematic review. Hormone Behav 128:104912

Lerner JE, Martin JI, Gorsky GS (2021) More than an apple a day: Factors associated with avoidance of doctor visits among transgender, gender nonconforming, and nonbinary people in the USA. Sex Res Soc Policy 18(2):409–426

Lett E, Abrams MP, Gold A, Fullerton F-A, Everhart A (2022) Ethnoracial inequities in access to gender-affirming mental health care and psychological distress among transgender adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 57:963–971

Lett E, Asabor E, Beltrán S, Cannon AM, Arah OA (2022) Conceptualizing, contextualizing, and operationalizing race in quantitative health sciences research. Ann Fam Med 20(2):157–163

Marrero RJ, Fumero A, de Miguel A, Peñate W (2020) Psychological factors involved in psychopharmacological medication adherence in mental health patients: a systematic review. Patient Educ Counsel 103(10):2116–2131

Matsuno E, Budge SL (2017) Non-binary/genderqueer identities: a critical review of the literature. Curr Sex Health Rep 9(3):116–120

Mizock L, Woodrum TD, Riley J, Sotilleo EA, Yuen N, Ormerod AJ (2017) Coping with transphobia in employment: strategies used by transgender and gender-diverse people in the United States. Int J Transgend 18(3):282–294

Motosko C, Zakhem G, Pomeranz M, Hazen A (2019) Acne: a side‐effect of masculinizing hormonal therapy in transgender patients. Br J Dermatol 180(1):26–30

Motta G, Crespi C, Mineccia V, Brustio PR, Manieri C, Lanfranco F (2018) Does testosterone treatment increase anger expression in a population of transgender men? J Sex Med 15(1):94–101

Parra‐Frutos I (2014) Controlling the Type I error rate by using the nonparametric bootstrap when comparing means. Br J Math Stat Psychol 67(1):117–132

Puckett JA, Cleary P, Rossman K, Mustanski B, Newcomb ME (2018) Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sex Res Soc Policy 15(1):48–59

Ratanawongsa N, Karter AJ, Parker MM, Lyles CR, Heisler M, Moffet HH, Adler N, Warton EM, Schillinger D (2013) Communication and medication refill adherence: the Diabetes Study of Northern California. JAMA Intern Med 173(3):210–218

Redfern JS, Sinclair B (2014) Improving health care encounters and communication with transgender patients. J Commun Healthcare 7(1):25–40

Reisner SL, Deutsch MB, Bhasin S, Bockting W, Brown GR, Feldman J, Garofalo R, Kreukels B, Radix A, Safer JD (2016) Advancing methods for US transgender health research. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diab Obes 23(2):198

Reisner SL, Hughto JM (2019) Comparing the health of non-binary and binary transgender adults in a statewide non-probability sample. PLoS ONE 14(8):e0221583

Restar A, Jin H, Breslow A, Reisner SL, Mimiaga M, Cahill S, Hughto JM (2020) Legal gender marker and name change is associated with lower negative emotional response to gender-based mistreatment and improve mental health outcomes among trans populations. SSM Popul Health 11:100595

Restar A, Jin H, Breslow AS, Surace A, Antebi-Gruszka N, Kuhns L, Reisner SL, Garofalo R, Mimiaga MJ (2019) Developmental milestones in young transgender women in two American cities: results from a racially and ethnically diverse sample. Transgender Health 4(1):162–167

Roller CG, Sedlak C, Draucker CB (2015) Navigating the system: how transgender individuals engage in health care services. J Nurs Scholarship 47(5):417–424

Sabaté E, Sabaté E (2003) Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization

Scandurra C, Mezza F, Maldonato NM, Bottone M, Bochicchio V, Valerio P, Vitelli R (2019) Health of non-binary and genderqueer people: a systematic review. Front Psychol 10:1453

Seelman KL, Colón-Diaz MJ, LeCroix RH, Xavier-Brier M, Kattari L (2017) Transgender noninclusive healthcare and delaying care because of fear: connections to general health and mental health among transgender adults. Transgender Health 2(1):17–28

Silva DC, Salati LR, Villas-Bôas AP, Schwarz K, Fontanari AM, Soll B, Costa AB, Hirakata V, Schneider M, Lobato MIR (2021) Factors associated with ruminative thinking in individuals with gender dysphoria. Front Psychiatry 12:799

Sperber J, Landers S, Lawrence S (2005) Access to health care for transgendered persons: Results of a needs assessment in Boston. Int J Transgenderism 8(2-3):75–91

Stroumsa D, Crissman HP, Dalton VK, Kolenic G, Richardson CR (2020) Insurance coverage and use of hormones among transgender respondents to a National Survey. Ann Fam Med 18(6):528–534

T’Sjoen G, Arcelus J, Gooren L, Klink DT, Tangpricha V (2019) Endocrinology of transgender medicine. Endocr Rev 40(1):97–117

Thoreson N, Park JA, Grasso C, Potter J, King DS, Marc LG, Shen C, Peebles JK, Dommasch ED (2021) Incidence and factors associated with acne among transgender patients receiving masculinizing hormone therapy. JAMA Dermatol 157(3):290–295

Tibshirani R (1996) Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. J R Stat Soc Ser B 58(1):267–288

US Census (2020a) Quick facts: Massachusetts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2020 from http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/25

US Census (2020b) Quick facts: Rhode Island. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 26, 2020 from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/RI,US/PST045219

Webb AJ, McManus D, Rouse GE, Vonderheyde R, Topal JE (2020) Implications for medication dosing for transgender patients: a review of the literature and recommendations for pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Phar 77(6):427–433

White Hughto JM, Reisner SL (2016) A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgender Health 1(1):21–31

Zaliznyak M, Jung EE, Bresee C, Garcia MM (2021) Which US States’ medicaid programs provide coverage for gender-affirming hormone therapy and gender-affirming genital surgery for transgender patients?: a state-by-state review, and a study detailing the patient experience to confirm coverage of services. J Sex Med 18(2):410–422

Zolnierek KBH, DiMatteo MR (2009) Physician communication and patient adherence to treatment: a meta-analysis. Med Care 47(8):826

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of this study, and our research members for their assistance with this study: Jackson McMahon, Christopher Santostefano, David Pletta, and Ryan Segur. This work is supported by the Providence/Boston Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P30AI042853. Dr. Restar is supported by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Policy Research Scholar. Drs. Restar and Radix are supported by the Yale School of Public Health’s Research Education Institute for Diverse Scholars (REIDS), funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R25MH087217). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the sponsors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR and JH were involved in the conceptualization of this paper. AR and JH designed the analysis for this paper. AR conducted the data analysis. AR, EJD, and HG-D wrote the paper. All authors analyzed and interpreted the data, and significantly reviewed/edited the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (The Fenway Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Fenway Health in Boston, Massachusetts) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. The ethics approval number for the study was: 1280264-2.

Informed consent

Electronic written informed consent was attained for all enrolled participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Restar, A., Dusic, E.J., Garrison-Desany, H. et al. Gender affirming hormone therapy dosing behaviors among transgender and nonbinary adults. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 304 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01291-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01291-5

This article is cited by

-

Gender-affirming hormone therapy in transgender women and risk of prostate cancer: pathophysiological mechanisms and clinical implications

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2024)

-

Improving the cardiovascular health care of transgender and non-binary persons

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2023)

-

The Utility of Preclinical Models in Understanding the Bone Health of Transgender Individuals Undergoing Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2023)

-

Mapping Community-Engaged Implementation Strategies with Transgender Scientists, Stakeholders, and Trans-Led Community Organizations

Current HIV/AIDS Reports (2023)