Abstract

The social, discursive practice of othering in violent extremist discourse serves to present outgroups as distant yet real threats to the ideological and physical territories of an ingroup which a terrorist claims to represent. However, the role of grammatical choices (namely, non/transactive construction, voice, and mood) in enacting the othering act within the context of radicalisation to terrorism remains to be empirically verified. This paper explores the patterning and pragmatic functions—namely in framing situations, coercing into violence, and legitimising hostile actions against Others—of the syntactic structure of the othering utterances. The othering utterances, as realized in a set of eight public statements produced by former al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, were sorted manually and analysed qualitatively to help understand and showcase how grammar was strategically leveraged in the process of radicalisation. Results show that the act of othering in the dataset operates within the victimization and injustice frameworks to morally sanction antagonism and aggression via: (i) overt othering, where transactive construction, only declarative mood and active voice are used, and (ii) covert othering, in which nontransactive construction, any mood type, and passive voice are utilized. Overt othering foregrounds, through assertions and statements of presumed facts, the negative agentive role of Others and the diagnostic framing of the causal relationships between Others and negative experiences. Covert othering backgrounds this agentive role to place prominence on immoral actions and to serve in the motivational function of framing. The grammatical patterns provide evidence of the strategic character of OBL’s verbal aggression and how different mood types tend to construct the directive, illocutionary point of the utterances and to enact prognostic framing. The analytical strategy aids in threat assessment and preventing radicalisation by sensitizing assessors to, first, the kind of semiotic clues to engagement in the social and discursive process of radicalisation where utterances count as calls for action and activators of a reality of deontology, and, second, to the social functioning of terrorist texts in: (i) promoting putative readers’ awareness of particular outgroups, and (ii) ideological positioning and encouraging and legitimating violence that is liberty, loyalty and care metavalues-based.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Linguistic analysis of terrorism cases has been found to be useful in helping security investigators to understand terrorist discourse, explore terrorists’ ideological schemas (i.e. how terrorists think about what is being talked about) and identify the activities in which terrorists engage (Shuy, 2020). To achieve this linguistic support for intelligence analysis and security tasks, a linguist may draw on a range of principles and tools including those in the disciplines of syntax, pragmatics and semantics (Shuy, 2010). Contributing to a better understanding of the discursive practice of othering and its moral reasoning in the context of radicalisation to terrorism, this paper showcases the exploration of different othering strategies, the syntactic resources employed in these strategies and their pragmatic functions, as realized in eight public statements produced by Osama bin Laden (OBL, henceforth). Since pragmatics needs to “hook up” not only to syntax and lexis but also to semantics, particularly, when interpreting the illocutionary acts or points of utterances (Butler, 1988, p. 96), this paper expands its analytic scope to also include this pragmatics semantics-hook up in the act of othering.

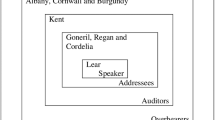

In this paper, ‘othering’ refers to the interpersonal act of categorising the world into ‘Us’ versus ‘Them’ based on (i) representing via grammar who is doing what to whom, and (ii) building a dichotomy of opposing social groups with distinct master identities whereby outgroups are depicted as a morally distant, yet ‘real’ ideological and physical threat to the ingroup that an author (e.g. OBL) allegedly represents. The significance of examining the act of othering in terrorist context lies in illustrating how investigators may obtain a fuller understanding of the strategic character of a terrorist’s verbal aggression via identifying the grammatical patterns used in othering and framing the divisive inter-group relationship. Exactly what role these grammatical choices play and in which pattern they manifest in terrorist language remain to be empirically verified, which is a contribution of this paper. This paper takes the dataset produced by OBL as a case study. The paper also seeks to add to the tools available for unlocking the links between morality, hate, identity, framing, and the triune act of “stancetaking” (i.e. evaluation, dis/alignment, and ideological positioning) (Du Bois, 2007, p. 162) construed in the language choices made in the OBL radicalising texts. Focus is placed on how the syntactic construction serves to radicalise putative readers, to coerce (i.e. generate fear of ‘Others’ in the ingroup members) (e.g. Cap, 2017), and to legitimise hostility and aggression against outgroups. The grammatical choices are taken as markers of managing, (re)producing and/or sustaining negative perceptions of outgroups, and inter-group antagonism and aggressive relations. That is, in Crystal’s (2008, p. 379) terms, these grammatical choices are considered here features that do play a role in the social functioning of terrorist texts and in “expressing a range of attitudes and relationships”.

Literature review

There are many approaches to the study of othering inside and outside linguistics and to its social and ideological functions in online and offline communication and in contexts of, for example, hate, racism, Islamophobia, media and politics (see e.g. Holslag, 2015; Silva, 2017; Lams, 2017, 2018; Farkas et al., 2018; Perry and Mason, 2018). Othering, in these studies and also in this paper, is considered an ideological, social and discursive practice par excellence. That is, since a language user can construct multiple versions of the social experiences by various linguistic choices, the strategic choice to use particular grammatical options in discourse is never devoid of their ideological aspect or social impact (Silverstein, 1992, p. 313; Butt et al., 2004). In this study, I adopt the general theoretical orientation that inter-group practice of othering and hostile relationships are ideologically motivated and can manifest in the patterns of the “relationship between language form [choice] and language use [which] involves cognitive processes” (Verschueren, 2009, pp. 1–2). The practice of othering in terrorist communication is considered—in Min’s (2008, p. 74) terms—an “intrinsically face-threatening act” which operates contrary to Leech’s (1980, 1983) maxims of politeness (particularly the sympathy maxim) in relation to viewing outgroups (in contrast to viewing an ingroup). While the notion of politeness—developed by Brown and Levinson (1978, 1987)—is usually employed “to show awareness” of another person’s or group’s face (Yule, 1996, p. 60), in the practice of othering a terrorist utilizes ‘impoliteness’ (e.g. Culpeper, 2011) as public face attacks to show and promote awareness of outgroups’ negative agentive role, as a way to cause offence or incite for an offence against people with distinct master identities (e.g. religions) and social affiliations.

The concept of affiliation construction—i.e. constructing group membership (Higgins, 2007)—that is based on master identities is also central to the act of othering and radicalising cross-border ingroup addressees to violence against ‘bad’ outgroups (see e.g. Straun, 2009; Mandel, 2010; Smith et al., 2016; Smith, 2018; Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021). Recent research into radicalised and violent extremist discourse (e.g. Chiluwa, 2015) reveals that promoting these affiliations while positively constructing an ingroup and negatively constructing particular outgroups is a major strategy used in radicalist discourse. This exploitation of identity and worldviews serves in influencing (i.e. constructing, maintaining, promoting, challenging and/or changing) the views of members of the ingroup and their perception of the way the world should (not) be, which ultimately promotes ingroup prejudices and radicalises into hostile inter-group relationships based on “an evaluative construct” of the world (Mandel, 2010; Adams et al., 2011, p. 5). In this study, first, radicalisation is considered to be an evaluative construct, and, second, attention is drawn to the master identities constructed in discourse and to the linguistic strategy of constructing agency and affectedness—in terms of who is presented with roles of Agency or Affectedness—as an evaluative strategy used to ideologically position putative readers to favour ingroup and disfavour outgroups (see White, 2006).

A well-established starting point to the study of the discursive construction of otherness is the analysis of sentence structure, primary participants and their roles—primarily the verbs with which the participants are associated and the different types of relationships these participants have to these verbs at the level of syntax (Sykes, 1988). By focusing on the construction of Agency and Affectedness, I argue, we can obtain a picture of how an extremist seeks to forge ingroup alignments, and disalignments with outgroups, making the perceptions of who belongs to the in/outgroup’s affiliation and who is assuming which role essential to the act of othering and radicalising into violence. This argument is aligned with recent research into the role of stancetaking and identity in terrorist discourse which has found challenges targeting ingroup values and master identities to be a basis for inciting for violence and justifying personal and relational identities (see e.g. Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021). That is, violence is promoted as “one form of response to these challenges” (Lutz and Lutz, 2008, p. 100) and is justified on the basis that a terrorist is “distant from/or superior to ‘Others’ vs. close to in-group’s members” (relational identity) and is thus “aggressive and antagonistic towards ‘Others’ vs. caring towards in-group’s members” (personal identity) (Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021, p. 10). In addition, aligned with Sykes’ (1988) suggestion that a sentence structure-based analysis of the act of othering is useful, this paper allows for focusing on (i) participants’ roles within a conflict context which “can also be impacted upon by syntactic transformation”, and (ii) who is in the Agent role or Patient role undergoing particular experiences (Thetela, 2001, p. 352). Pandey (2004) has found that focusing on some syntactic features can yield insights into how strategic choices of grammar in particular contexts may play a role in polarising identities and defining a ‘Them’ versus ‘Us’ opposition. For example, the use of passive or active voice can mitigate or stress othering (Pandey, 2004).

This ‘Self versus Others’ construction of relationships and roles serves to promote collective hate actions and manages to present Others as a threat and the ingroup’s violence as morally justified (Reicher et al., 2008). In this paper, attention is also drawn to the moral reasoning of ‘our’ violence against Others and to the “moral disengagement” from outgroups, specifically to “diffusion of responsibility”, that is, assigning blame and responsibility to outgroups to lay a moral ground for justifying hostility and violence against them (Bandura, 2016, p. 62). In short, I consider the moral frameworks, or alternatively metavalues, that OBL draws on to provide clues to an extremist’s predisposition and assumptions about Self and moral reasonings behind othering and hostility. Given the disdain many feel for terrorists and radical groups (Khosrokhavar, 2014), I argue that a terrorist mobilises these moral expectations to discourse in order to establish a connection between the advocated violence and the ingroup addressees’ moral values so that the addressees are morally disengaged from Others (and their immoral acts) and morally engaged with the ingroup and for its benefit. According to Parvaresh (2019), a consideration of predispositions and assumptions can provide clues as to how certain experiences are responded to and how social roles, expectations, rights and duties are activated in discourse. Informed by recent literature on the moral foundations of evaluation and acts of impoliteness (e.g. Spencer-Oatey and Kádár, 2016; Kádár, 2017; Kádár et al., 2019), a particular set of metavalues can be identified as regulating and providing a reasoning for inter-group conflicts, evaluations and interpersonal relationships, just as a language user’s ideological and cultural moral orders can set expectations for metavalues such as ‘loyalty’ to the ingroup and ‘care’ for the ingroup’s vulnerability (Van Langenhove, 2017). The construction of Agency and Affectedness, I argue, can provide insights into the moral orders constructed in discourse and the morality underpinning the evaluative construct.

The grammatical construction of experiences can also serve to promote and manage awareness about Others and how to treat them through particular framing—i.e. organising situations and establishing “definitions of a situation” (Goffman, 1974, p. 10). Grammatical options can facilitate our making-sense of discursively constructed social experiences, in terms of communicating to putative readers a range of information about social actors and their roles and agency. This communication includes: informing about who should be viewed as being responsible for the ‘bad’ goings-on (the “diagnostic” function of framing); suggesting counteractions (the “prognostic” function); and motivating to violence as a duty (the “motivational” function)—for more on the social functions of framing in contexts of radicalisation to terrorism and social activism, see Smith (2018) and Benford and Snow (2000, pp. 615–618), respectively. This management of awareness thus has a rhetorical effect of guiding audiences on how they may structure a common worldview of a dichotomous representation of who is good versus evil, right versus wrong, acceptable versus unacceptable, and blameworthy versus praiseworthy—a representation that serves in presenting a violent goal as an ingroup’s collective enterprise (see also Cap, 2017, for similar argument).

Lams’ (2018) analysis of the discursive construction of otherness (in a different context though—that is, press narratives about immigrants) has identified a key role of language in the portrayal of outgroups and shaping the ingroup audience’s awareness of and attitudes towards a ‘negative’ reality (e.g. migration flows). Such portrayal stimulates the putative readers’ compassion or adversarial stance towards outgroups. Lams’ (2017) critical discourse analysis of Chinese official media’s linguistic construction of America and Japan has also highlighted the role of language in promoting Others as foreign and antagonist within a victim/aggressor framework. This promotion has also been accomplished through the grammatical choices made by politicians such as George W. Bush and military commanders like the British Lieutenant Colonel Tim Collins: to endow positive semantic roles to the exhorted coalition and troops deployed in Iraq and to allocate negative roles to the incited-against Iraqis, to ultimately legitimize the coalition’s operations in the 2003 war on Iraq (Butt et al., 2004).

In sum, as informed by the literature, this paper is concerned with three aspects of analysis of the act of othering. The first is the ideological positioning and alignment of ingroup readers against outgroup social actors as realized in the assigned roles of Agency and Affectedness. The second is the “identity work” (Tracy and Robles, 2002, p. 7) relating to informing an extremist’s linguistic structure to frame experiences in a way that rationalizes hostility and creates, presents, sustains or/and challenges groups with particular master identities (see e.g. Smith et al., 2016; Smith, 2018). The third is the moral underpinning of grammatical choices which can provide indications of predispositions and assumptions relating to how the world ought (not) to be and how certain experiences should be responded to. These three aspects are aligned with recent findings of sociological research on radicalisation to terrorism (e.g. Smith, 2018) in that terrorist narratives and belief systems and identity processes, which include framing social issues and experiences, are major facilitators of radicalisation to terrorism.

The grammatical choices used in the practice of othering are investigated in terms of the degree of directness, or alternatively foregroundedness and obliqueness. In other words, the grammatical choices are examined as to how direct or indirect, or alternatively “overt” or “covert” (Pandey, 2004, p. 161), othering is expressed and for what pragmatic purposes. This variable of directness is established based on the straightforwardness in the causal relationship established between outgroup participants and their negative actions that influence ‘Us’. This relationship can be demonstrated, for example, through naming or pronominal references in, for example, Agent versus Patient role. According to Sykes (1988), this role can be realized (in)directly in Subject and Object names/pronouns in (non)transactive and active or passive constructions. Of interest to this paper is also the influence of choice of mood type in the pragmatics of othering. The role of mood types (declarative, imperative, and interrogative) in the pragmatics of violent speech acts (e.g. communicated threats) has been found to be crucial in activating the parameter of coercion, exercising power, and realizing a violent actor’s commitment to violence (Martínez, 2013). As such, a particular choice of syntactic construction: can give rise to negotiated inter-group relationships and facilitate communication of information about different social actors and their social roles (Halliday and Matthiessen, 2014); and can enable us to identify the “illocutionary point” of an utterance, that is, its purpose, whether it is “assertive”, “directive”, “commissive”, “expressive” or a “declaration” (Searle, 1999, pp. 147–150).

Methodology

Data

Eight written public statements produced by OBL over 2001–2006 were analysed in this study. This paper does not seek to investigate othering in all texts of OBL, nor does it claim to provide findings that are representative of othering choices across other samples of OBL. Instead, it showcases how an extremist’s strategic, grammatical choices within a dataset can offer insights into the extremist’s aggression, audience manipulation and stoking hate, by shedding light on the foregroundedness of power relations. The eight statements were taken from the publicly available al-Buraq al-I’lamyiah’s ‘al-Archive al-Jami’ (i.e. the Collective Archive) of the OBL statements. The translations were drawn from sources such as the Al-Jazeera news network, the CIA Foreign Broadcast Information Service’s ‘January 2004 report’, and the author of this paper (see e.g. FBIS Report, 2006). The texts analysed were used in Etaywe and Zappavigna (2021) to identify the patterns of attitudinal meanings realized in repeated, evaluatively loaded lexical items, as a means to get at OBL’s personal and relational identities. For the purpose of this paper, English translations of the same statements were analysed after clause constructions were reviewed and verified as faithful to the source texts’ grammatical structures as determined through comparison with the original texts. This review was undertaken by the author, a native speaker of Arabic and a recognized English–Arabic translator.

The texts are from OBL’s letters and speeches, or alternatively public statements of his goals and values, and they communicate inciting and threatening messages to multiple audiences (see Table 1). OBL1 and OBL3 are texts that communicate threats against the American people in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks and in light of the US aggression against Iraq. OBL2, OBL4 and OBL5 address the Iraqis and Muslims in general, inciting them to jihad against the American troops in Iraq. OBL6 is a statement of incitement against Prince Abdullah bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia and his support of the Americans and his initiative for peace with Israel. OBL7 and OBL8 address the Pakistani and Afghan people, respectively, and incite them for jihad against the US-led operations in Afghanistan.

The OBL statements were produced in the period following the 9/11 attacks on the USA in 2001. In this period, the US President George W. Bush declared the war against al-Qaeda and a number of Muslim countries (e.g. Afghanistan and Iraq) as a ‘crusade’, and Bush led a polarising campaign where countries worldwide were invited to choose to be either with or against America in this war (Ray, 2017). The aftermath of the 9/11 attacks created greater distrust between the Americans and Arab/Muslim societies (Miller, 2015), particularly in light of declaring the so-called ‘global war against terrorism’ which targeted Muslim majority countries. In this polarising sociopolitical environment, the OBL statements were also of polarising and radicalising nature (Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021). OBL’s public statements, thus, offer compellingly appropriate material for examining othering as a form of language aggression performed in a war context, and give a representation of utterances and grammatical structures used in the act of othering in conflict context. The offensive potential of the grammatical choices in the dataset is interpreted in relation to the sociopolitical environment that followed the 9/11 attacks. The OBL linguistic choices are taken as being influenced by his view of the conflict with the Americans—that is, the US-led war is considered oppression, aggression and a crusade aimed at subjugating Muslims and desecrating Islam and, thus, requires Muslims to fight the US aggression and drive the Americans and their allies out of the Muslim countries (Miller, 2015). Since I am more concerned in this paper with the grammatical choices, references to the context of the exemplified utterances are included in the “Results and discussion” section in brackets after each example, e.g. (OBL1). In addition, a short elaboration on the context of an utterance is provided where needed.

Data analysis procedure

The analysis of the othering utterances at the syntactic level was undertaken as a lens on audience manipulation and negotiating power relation-enactment and blameworthiness. The meaning of an utterance or alternatively “a sentence [was] determined by the meaning of the words and the syntactical arrangement of the words in the sentence” (Searle, 1999, p. 140). To obtain a manageable number of utterances, the analysis focused on the utterances in which violent parts of speech (i.e. words with violent content, e.g. death, killed, bombardment) (see also Muschalik, 2018) were used and reference to primary participants was obvious. Analogising with Leets and Giles’ (1997, p. 262) “fighting words”, the analysed utterances were referred to as fighting utterances, given the fighting colour (i.e. load) strung throughout these utterances. The choice of examining the primary participants in these utterances was driven by two factors. First, naming a third person (e.g. Americans, Bush) as well as using additional referents (e.g. third person pronouns such as they, he) reflects that the author has defined the ‘our’ group to a great extent by the existence of opposing Others (see also Pennebaker and Chung, 2007). Second, this analysis departs from the premise of ‘existential’ presupposition (see Yule, 1996), that is, the explicit naming of and pronominal reference to rival or opposing primary participants (i.e. America) presuppose that the ‘X’ Other and ‘Their’ actions exist or are real. AntConc software (Anthony, 2019) was used to identify the prominent actors, their pronominal references and the predicates associated with these actors. This exploration allowed for focusing on the primary participants in discourse and considering the participants and their master identities to be the “deictic centre” (Cap, 2017, p. 5) of the othering practice in the dataset. The violent parts of speech that occurred more than once in the dataset were identified, using AntConc. Then, the construction of the utterances containing these words and the primary participants (or additional referents to them, e.g. pronouns) was analysed. For more accuracy in the choice of utterances analysed, the exact utterances were sorted manually and were analysed qualitatively.

This paper takes an independent “clause as speech act” (Halliday, 1973, p. 40). It also considers OBL’s strategic choices “in the construction of linguistic forms—sentences” to be serving in realizing “options in meaning […] and behaviour” (Halliday, 1973, p. 52). Each fighting utterance or sentence was examined manually to identify its

-

syntactic construction—transactive or non-transactive, i.e. clauses with ‘agent-verb-affected participant’ construction or clauses with one participant construction, respectively (see Examples 1 and 16, respectively, in the section “Results and discussion”).

-

mood—clause type that is declarative, imperative or interrogative, i.e. clauses with Subject^Finite, Predicator (non-finite) or Finite^Subject sequence, respectively (as in Examples 1, 10, and 19, respectively).

-

voice—that is either active, i.e. a clause with normal linking of Agent to Subject and Patient to Object, or passive which links Patient to Subject (see Examples 1 and 10, respectively).

Inspired by Cap’s (2017) discursive functions of othering and threat-construction as well as by Pandey’s (2004) overt and covert othering, the grammatical selections were mapped onto two broad types of othering:

-

Overt othering: in which the responsibility for perceived negative actions is overtly assigned to the (‘Other’) Agent as a basis for othering. That is, the grammatical choices of construction, mood and voice are strategically deployed to foreground the exercise of power by ‘Others’ as well as the casual relationships between ‘Others’ and negatively perceived actions/‘realities’ which are targeting ‘Our’ group. These choices are thought of as being in service of the conceptualisation of others as a threat to ‘Us’, which serves to exclude ‘Them’ in a step towards coercing (generating fear of ‘Others’) and legitimating ‘Our’ hostile actions.

-

Covert othering: in which the causal relationship and responsibility for negative actions targeting ‘Us’ is backgrounded; yet it can be found to be relative to backgrounded ‘Others’. The causal relationship can be signalled by grammatical resources such as a possessive pronoun (e.g. our), prepositional circumstantials with ‘by’ and ‘from’, premodification or postmodification of a noun, and so on (e.g. van Leeuwen, 1996).

This mapping of grammatical selections onto the types of othering aims to highlight the directness in the realization of who is responsible for the status quo and who is doing what to whom/what. This realization is taken as a clue to the practice of othering which is chiefly driven by viewing the self/ingroup as being victimised and outgroups as being the victimizers. This kind of evaluative construction, I argue, enables a terrorist to influence the stances and actions of ingroup audiences against outgroups.

The illocutionary points of the othering utterances—such as getting the putative reader to do something, thus a ‘directive’ point—were examined to provide evidence of the purpose behind the utterances as acts of othering. The aim is to understand the coercive and offensive potential of OBL’s grammatical selections alongside their pragmatic functions. In so doing, I adopt Searle’s (1999) notion of illocutionary points (i.e. what ‘count as’, for example, a directive point or an assertive point) to establish a link between the mood type of an utterance and its pragmatic purpose in terrorist discourse. The focus of this analysis is on whether the mood type asserts or requests information about or actions towards primary social actors, to enhance our understanding of the role of grammar insofar as asserting or requesting information and actions. This role sensitizes us to the consideration of the epistemic and social status of the author (i.e. OBL) as a knowing person and a person of higher moral status or a commander of moral actions, given that “performing illocutionary acts is imposing a type of status function” in an interpersonal relationship (Searle, 1999, p. 147). I argue for Heritage’s (2012, p. 7) contention that consideration of the epistemic status of a speaker in relation to the selected grammatical forms is “a critical resource for determining the status of the utterance as an action” for radicalising stances and perceptions.

The othering paradigm of analysis was based on the construction of ‘Us’, the oppressed and undergoing injustices, and ‘Them’, the oppressors, through grammatical choices. To sensitize us to the role of identity work in informing the linguistic structure of framing the issues and situations that al-Qaeda seeks to address, within the oppressed Muslims versus oppressor others dichotomy, three framing functions were considered as informed by Benford and Snow (2000):

-

Diagnostic framing: in which a structure focuses on identification of a problem and source of the problem.

-

Motivational framing: in which a structure serves in providing a call or rationale for engaging in collective, violent actions.

-

Prognostic framing: in which a structure implies the articulation of proposed solutions, or an action that addresses the problem (e.g. incitement to ‘martyrhood operations’ against the Americans, and ‘civil disobedience’ against Arab rulers who support the Americans).

In addition, for a better understanding of the moral assumptions and considerations underpinning the assigning of agency and affectedness roles of participants, four moral metavalues were considered. In so doing, I draw on recent research into the morality of social actions and evaluation suggesting that evaluation in aggression and conflictive contexts is sustained by culturally and contextually sensitive, moral foundations (see e.g. Ståhl et al., 2016; Parvaresh, 2019; Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021). These are: ingroup/loyalty; authority/(dis)respect; harm/care; and liberty/oppression. In this paper, the allocated social role (Agent or Patient) and the illocutionary points are taken—in Van Langenhove’s (2017, p. 1) terms—“as the activators of moral orders” and contributors to our understanding of the link between agency and social structure.

Results and discussion

This section reports and discusses the findings of the qualitative analysis of the fighting utterances. The following subsections highlight the active role of the language user (OBL) in discourse production and the pursued pragmatic functions, in relation to the framework of analysis of the two types of othering: overt othering, and covert othering of primary deictic centers—America and the American allies (e.g. Israel) who belong to two master identities that are distinct from OBL’s (Christianity and Judaism). Prior to delving into the details of types of othering, their realizations and pragmatic functions, two primary deictic centers are identified:

-

America/American* (60 explicit naming occurrences);

-

Muslim(s) (80 occurrences), including people of Lebanon, Palestine, Pakistan, Iraq, etc.

Additional references to the primary participants come under two main polarised categories of pronouns:

-

First person pronouns (I, we, our, us), which refer to the ingroup, totalling 227 occurrences;

-

Third person pronouns (they, their, them, he, his), which refer to outgroups and outgroup agents such as George W. Bush, totalling 248 occurrences.

The pronominal references to these primary participants are in subjective case (e.g. we, they, he, I), possessive form (e.g. our, their, his), and objective case (e.g. them, us) which makes focusing on the roles assigned to the primary participants crucial in the overt and covert acts of othering.

Overt othering: Grammatical choices and their pragmatic functions

The analysis has revealed an author who is decidedly interpersonally involved in the communication and the act of othering, particularly in terms of overt assigning of agency and affectedness roles to the primary social actors. The findings show patterns of use of grammatical choices that have constructed a paradigm of Agents and Patients, where, on the one hand, ‘Them’ are constructed explicitly as Agents and responsible for harm caused to ‘Us’. On the other hand, ‘Us’ are constructed as Patients of ‘Their’ negative actions, or as Agents of negative acts that are constructed as being morally justified and reactive actions. These findings provide support to previous research (e.g. Bandura, 2016; Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021) that blameworthiness and shifting-responsibility are key mechanisms through which a terrorist selectively morally disengages from accountability for harmful conduct they cause against outgroups.

To elaborate, one pattern of grammatical choices that are used in overt othering manifests in the repeated employment of ‘Them’ as Agent and ‘Us’ as Patient. Consider the examples below where the fighting parts of speech are in bold. For instance, in Example 1, ‘The American forces’ are Agent (Subject) of the process (Verb) ‘attacked’ while ‘us’ are Patient, that is, undergoing the harm of others. In Example 2, America is the Agent of permitting ‘the Israelis’ to become Agent of a process (invade) whose Patient is ‘Lebanon’. In Example 3, ‘They’ are Agent of the process ‘terrorise’ while the ingroup’s members in Lebanon and Palestine are in Patient role. In Example 4, the Americans are also the Agent of the process (have supported); and the “beneficialised” (Van Leeuwen, 1996, p. 43) of this support are ‘the oppressor’ while the ingroup’s members, that is, ‘the innocent child’, are the Patient (indirect Object) as realized by the grammatical signal (i.e. preposition) ‘against’. In Example 5-a ‘Islam’ is the Patient undergoing the effect of the process ‘fight’, and so is ‘all human values’ (i.e. it is the Patient) undergoing the effect of the process ‘trampled’ that is acted by ‘America’ (Example 5-b). This pattern of direct assignment of Agency and Affectedness roles accords with previous work (e.g. Thetela, 2001) on the impact of syntactic features on promoting who is suffering and who is responsible for this suffering, and yielding insights into how these syntactic features play a role in conflict contexts in polarizing the primary social groups on the basis of the master identities of the agents and the affected (i.e. the Americans and their allies, and Muslims, respectively). This syntactic pattern serves to construct otherness by building stereotypical images of social groups based on their socioreligious affiliations and their associated actions.

-

(1)

The American forces [Subject: Agent] attacked [Verb] us [Object: Patient] with smart bombs, bombs weighing thousands of pounds, cluster bombs, and bunker busters. (OBL5)

-

(2)

…America [Subject: Agent] permitted [Verb] the Israelis to invade [Verb] Lebanon [Object: Patient] supported by the American 3rd Fleet. (OBL1)

-

(3)

They [the Israelis, the US ally] [Subject: Agent] terrorise [Verb] the women and children [Object: Patient], and kill [Verb] and capture [Verb] the men [Object: Patient]. (OBL1)

-

(4)

They [the Americans] [Subject: Agent] have supported the oppressor against the innocent child [Object: Patient]! (OBL4)

-

(5)

a. They [Bush and his supporters] [Subject: Agent] came out to fight [Verb] Islam [Object: Patient] under the falsifying name of ‘fighting terrorism’. (OBL4)

b. …America… [Subject: Agent] has trampled [Verb] all human values… [Object: Patient]. (OBL8)

The grammatical choices such as those in the examples above tend to realize: the enactment of responsibility-attribution; the construction of a straightforward causal relationship between the Agent and the processes targeting ‘Us’; the presentation of who is in a position of power; and the divisive function of OBL’s texts. This direct responsibility-attribution and structure of ‘Their’ aggressive agentive role serve the purpose of diagnostic framing, that is, the overt identification of the problem (e.g. injustice and victimization) and the source of the problem who should be blamed. That is, within this pattern of victimhood construction, OBL maintains conventional Agent-Patient roles through the use of transactive constructions. He also directly links Agent to Subject and Patient to Object in utterances in active voice. In addition, the declarative mood has enabled conveying statements of presumed facts and opinions about ‘Us’ and the Americans as ‘Others’.

OBL’s utterances as such proffer othering as—in Bourdieu’s (1991, p. 66) terms—an exchange that is “established within a particular symbolic relation of power”. The pattern of the grammatical choices of construction, voice and mood has served, so far, the coercive function of seeking to influence the ingroup audience’s stances, given projected personal physical consequences. In other words, the strategic choice of grammatical resources appeared to play a main role in the strategic stimulation of fear of and hostility towards the American ‘aggressors’, based on the constructed Patient role of ‘Us’. The assigned roles thus ultimately serve to urge for supporting ‘Us’. Put differently, the roles activate the motivational framing, that is, they provide a rationale such as a religious motive, as in Example 5-a above, or a group duty, for engaging in violence as an identity-protection enterprise. As such, this construction of the world appears to enact—in Spencer-Oatey and Kádár’s (2016) terms—interpersonal-links metavalues (namely, the ‘ingroup/loyalty’ metavalue) and inter-group relationships metavalues (chiefly, the ‘harm/care’ metavalue). The patterning of syntactic construction appears to be driven by the moral reasoning of obligations towards defending the ingroup and caring for harm being imposed upon the ingroup.

This moral reasoning has also been realized grammatically in the pattern of construction of ‘Our’ Agent role and/or ‘Their’ Patient role. The moral function of this construction is based on othering the Patient against whom ‘Our’ Agentive role has been brought about as a reaction and a defensive act. That is, the act of othering is uttered after an offence by the ‘Other’. I term this kind of othering retrospective othering (cf. Aijmer, 1996). Consider Example 6 where ‘we’ is the Agent of the violent processes ‘punish’ and ‘destroy’, and this agentive role is constructed as being in retrospect of what the Americans previously did to ‘Us’ in Lebanon and elsewhere and thus ‘so that they [the Americans] taste some of what we tasted’. Similarly, ‘it’ (referring to America, in Example 7) is in Patient role while ‘Allah’ (Subject) is presented as an ingroup Agent. OBL’s utterances as such proffer othering as—in Bourdieu’s (1991, p. 66) terms—an exchange that is “capable of procuring a certain material or symbolic profit” for al-Qaeda as well as the wider cultural/religious ingroup. ‘Their’ Agentive role in previous aggression has served as premise for the retrospective othering that morally legitimises ‘Our’ reactive Agentive role in violence within the ‘liberty/oppression’ moral framework. That is, the ‘Our’ Agent-‘Their’ Patient syntactic construction appears to be underpinned by values that are concerned with resentment to oppression and outgroups that are dominating ‘Our’ group or restricting ‘Our’ right to freedom. The construction of ‘Us’ as Agents is, thus, deployed—in Ståhl et al. (2016) terms—in response to actions of dominators or to signs of restricting ‘Our’ freedom, which serves to encourage actions to come together in solidarity for preserving freedom and to overcome the oppressors.

-

(6)

[W]e [Subject: Agent] should punish [Verb] the oppressor in kind, and should destroy [Verb] towers in America \(\underline {\underline{so\;that}}\) they taste some of what we tasted, and they refrain from killing our women and children. (OBL1)

-

(7)

Here is America! Allah [Subject: Agent] the glorified and the exalted has hit [Verb] it [Object: Patient] in one of its killing points, destroying its greatest buildings! (OBL4)

Othering utterances, as shown in Examples 1–7 above, offer evidence of patterns of syntactic choices that OBL deploys to foreground the causal relationship and responsibility for the brought about state of affairs. The choices, which have enabled OBL to overtly other the Americans and their allies, are:

-

Transactive construction;

-

Active voice construction;

-

ONLY declarative structure: which encodes the othering utterances with indicative mood type that conveys assertions or statements of presumed facts about ‘Their’ group versus ‘Our’ group or communicates the state of affairs which the threatening ‘Other’ has brought about or will be responsible for bringing it about.

In sum, the analysis of OBL’s grammatical choices has revealed the construction of overt othering. They display how OBL has sought to foreground others as being responsible for negative actions. That is, others are either the Agent of actions affecting ‘Us’ or the Patient of legitimated actions by ‘Us’. These grammatical choices have been strategically deployed to conceptualise ‘Others’ as a physical threat to ‘Us’ as well as an ideological threat to ‘Our’ symbolic self (i.e. the Muslim Ummah—the body of Muslim communities worldwide), which rhetorically serves in legitimising violence against outgroups. These findings offer support to previous research on threat-construction as a means for legitimising ingroup violence (e.g. Cap, 2017; Reicher et al., 2008). Findings also accord with Lams’ (2018) argument that such endowment of agency roles to participants serves to promote awareness of ingroup audiences about events with self-serving bias, and to stimulate creation of a discourse of moral panic.

This stimulation has invested in the declarative syntax which facilitates the process of giving information by OBL as a knowing and thus informing person of the ‘true’ events. In other words, the declarative mood has been used to serve—in Heritage’s (2012) terms—in presenting the othering-information, which is within the speaker’s epistemic domain, as a basis for the encouraged social relationships and antagonistic actions against ‘Others’. The declarative mood tends to be deployed as—in Van Langenhove’s (2017) terms—an activator of moral orders and an enabler for certain positioning of moral agency based on assertions about the world. The choice of declarative mood emphasizes the illocutionary point of the othering utterances, which is here—in Cap’s (2017, p. 12) terms—of an “assertion-directive” link. That is, the illocutionary point is, first, assertive in that the utterances serve in sanctioning enactment of aggressive interpersonal relationships, which is proportionate with Lams’ (2017) finding on the role of assertive speech acts in othering. Second, this licensing of violence and its goal has the rhetorical effect of steering the ingroup addressees towards violence and is thus of directive point. The declarative structure choice also serves to activate the point of counting the utterance as committing the author to the truth of the propositional content about ‘Others’ and the subsequent sanctioning of violence. This assertion-based sanctioning could also be enhanced by grammatical choices such as the conjunction ‘so that’ in Example 6, where ‘so that’ (double underlined) signalled rationalization—i.e. as a form of legitimation (see Van Leeuwen 2007)—of violent practices by reference to their effects or goals, which is ‘so that…they [the Americans] refrain from killing our women and children’. Having reported and discussed the findings regarding overt othering, the next subsection focuses on covert othering.

Covert othering: Grammatical choices and their pragmatic functions

The analysis undertaken provides evidence of covert othering-enactment, where the cause-effect relationship is backgrounded through a set of syntactic transformations. These include, inter alia, the use of passive voice. Eighty-six sentences of passive structure are observed in the dataset, revealing the strategic combination of voice options in the OBL texts where passive voice shifts the focus from who is doing what to the ‘immoral’ action offered as a basis of othering. For instance, in Examples 8, 9 and 10, OBL uses the passive construction. In this construction the ‘We’ group is in Subject position but with Patient role. The passive voice here enables the author to draw the putative readers’ attention more to others’ acts than to naming others, and to highlight the heinous, ‘unjustified’ and thus ‘immoral’ actions that are targeting ‘Us’. These findings support findings of previous research (e.g. Pandey, 2004; Thetela, 2001) that the use of passive voice facilitates amplifying and foregrounding the theme of ‘Us’ undergoing the negative acts while backgrounding the Agent, which here serves (i) in amplifying the discourse function of provoking hostility due to the physical harm brought about, and (ii) in activating the motivational framing function, urging for a response.

-

(8)

…[T]he bombardment began, many [Subject: Patient] were killed and injured, and many others were terrorised and displaced. (OBL5)

-

(9)

On 20 Rajab 1422 Hijri, corresponding to 7 October 2001 CE, our centres [Subject: Patient] were exposed to a concentrated bombing as of the first hour of the American campaign. (OBL5)

-

(10)

A million innocent children [Subject: Patient] are being killed up to this moment I am speaking to you! They [Subject: Patient] are being killed in Iraq for nothing wrong they did. (OBL4)

While an ‘Other’ can be identified from the co-text, using particular grammatical choices such as pre-modifications of nominalisation (e.g. American campaign, underlined in Example 9, and American law, in Example 11) is found to be a marker for identifying the Agent or who is in the “activated” role (van Leeuwen, 1996, p. 44). In Example 12, the Americans and their Israeli allies are the Agent realized in the post-modification of nominalisation (underlined) while ‘our people’ are the Patient signalled by the preposition, ‘against’ (double-underlined). Similarly, in Example 13, OBL uses the active voice where the Agent (America) is not in Subject position, but its agency is realized by the preposition (by America). In Example 14, while ‘America’ is the Agent of the killing act, America’s role is backgrounded by being placed in the Object position of the Verb ‘helped’. Notably, in Examples 11 and 14, the presentation of Self and Others is constructed in the that-clause, which is a construction that facilitates backgrounding the cause-effect relationship, a finding that is in accord with Pandey’s (2004). In Example 15, ‘the Americans” interference in and control over Saudi Arabia’s decision is backgrounded to the benefit of foregrounding the act of betrayal by ‘Prince Abdullah bin Abdelaziz’ who supports the Americans presence in Saudi Arabia and the American-led coalition against Iraq and Muslim countries, as realized in the Verb ‘betrayed’, which enacts the metavalue of disloyalty of Prince Abdullah to the ingroup. This foregrounding also provides a clue to the authority/(dis)respect metavalue, that is, this foregrounding is underpinned by assumptions about Arab officials in authority who are expected to be respectful to the Islamic traditions and to obey God’s rules in making coalitions, and in joining and defending the Muslim ingroup affiliation.

-

(11)

On that day, I was assured that injustice and intentional killing of innocent women and children is an approved American law, and that intimidation is freedom and democracy, while resistance is terrorism and backward. (OBL1)

-

(12)

But after enough was enough and we witnessed the injustice and tyranny of the American–Israeli coalition \(\underline {\underline{against\;our\;people}}\) in Palestine and Lebanon, the idea [of 9/11] came to my mind. (OBL1)

-

(13)

Amid this unjust war, the war of infidels and debauchees waged by America along with its allies and traitor-agents, we would like to emphasise on a number of important points. (OBL5)

-

(14)

We also make it clear that whoever helped America […] to kill Muslims in Iraq […] he is an apostate, outside of Islam circle, and it is permissible to take away their property and spill their blood. (OBL5)

-

(15)

Before that, he [Prince Abdullah bin Abdelaziz] betrayed the two holy mosques when he allowed the Americans to enter the country of the two holy mosques under the false allegations of the need for their assistance for three months. (OBL6)

In Examples 16 and 17, ‘they’ (the Americans) are in the Subject position, but they are the only participant; that is, OBL practices symbolic othering through a non-transactive construction where the Patient is not mentioned. Instead, the focus is on others’ ‘being’ and attributes, as realized in the Noun (‘evildoer’, in Example 16) and in the Object ‘falsehood’ (i.e. followers of falsehood), in a description of Arab officials, regimes, parties and religious scholars who support America in Iraq and the US-sponsored options in solving the conflict in Iraq and Palestine – thus negatively framing them within the butcher-victim framework: ‘They have supported the butcher against the victim’. This non-transactive construction serves in emphasizing the immorality of those included in the ‘Others’ category, which is also facilitated through the assertive point of the declarative structure which is underpinned by assumptions about loyalty to the ingroup and its jihadist option to solve the conflict. In Example 18, the Patient role of ingroup members (‘prisoners’) not only originates in the Object function but is also enhanced and signalled by the possessive pronoun ‘our’ (underlined) whereas the Agent role of ‘Them’ is signalled by a prepositional circumstantial with ‘in’ (double-underlined) that postmodifies the noun (‘the prisons’). Structure here also serves enacting the harm/care metavalue and the prognostic function of framing ‘Us’ versus ‘Them’ (the imprisoners). Noticeably, grammar still performs a key function of othering in these examples, but through different choices from those used in overt othering.

-

(16)

They are evildoers! (OBL4)

-

(17)

They have followed the falsehood! (OBL4)

-

(18)

O Allah, release our brother prisoners in the prisons of tyrants \({\underline {\underline {{\bf{in}}\;America}}},\, {\underline {\underline {Guantanamo}}},\, {\underline {\underline {occupied}}}\, {\underline {\underline {Palestine}}},\, {\underline {\underline {al-Riyadh}}},\, {\underline {\underline {and\;everywhere}}}\)—that You are ‘over all things competent.’ (OBL2)

The analysis has so far demonstrated that, in covert othering, the causal relationship as well as the responsibility for negative actions targeting ‘Us’ is not grammatically direct. A reader or an analyst, thus, cannot assume a one-to-one relationship between grammatical structure and function. This structure-function relationship can be realized as being backgrounded and thus requires accounting for contextual factors as well as stylistic considerations while considering the following strategic grammatical choices:

-

Non-transactive construction;

-

Passive voice;

-

Various forms of mood (as further demonstrated in subsection “Various forms of mood and their illocutionary points”), including declarative.

More on passive voice, declarative mood, and illocutionary points

As stressed earlier, in the utterances of passive voice and non-transactive construction where the agentive role of ‘Others’ and ‘Their’ responsibility is backgrounded, the negatively positioned ‘Others’ are realizable in the use of other grammatical signals such as possessive pronoun, prepositions, and pre-modification and/or post-modification of nominalisation. In addition, the declarative mood is found to be predominant. However, the illocutionary point of the declarative structures varies. For example, the declarative point in Example 14 above counts as bringing about a change in the world by representing it as having been changed through a declaration of war against those declared as ‘infidel’ and declaring that it is morally ‘permissible’ to take away the infidels’ lives and property. In other instances, such as Examples 8–11 and Examples 15, 16, the illocutionary point of the declarative structure is assertive; that is, it activates the author’s commitment to the truth of the propositional content about others. In addition, the assertion-commissive point is also identified, as in Example 12, which appears to serve in linking to OBL a commitment to undertake a particular course of action, as represented in the propositional content (to attack America in response to the US ‘injustice and tyranny’), while asserting the injustice and tyranny of America. The illocutionary points of the declarative structure as such vary to construct hostility as reasonable and aggression as warranted.

That said, I also argue that despite different grammatical choices in the acts of othering including active and passive voice structures (as in Examples 3 and 8, respectively), the characterization and framing of outgroups as aggressors, tyrants and unjust and the ingroup as victims remains explicitly similar in both examples. This means that the same perception of Self and Others would also remain the same in the OBL texts, even if we encounter a structure such as ‘Our women and children are terrorized by the Israelis’ or a structure such as that in Example 3 (‘They terrorise the women and children’). In both active and passive voice structures, we continue to have the broad categorisation of overt and covert othering, but we encounter an activation of two distinct functions of framing. In the passive structure, the perception of ‘Their’ immoral action and ‘Our’ vulnerable situation is stressed, a perception that is underpinned by OBL’s focus on and predispositions about the need to care for the vulnerable and the harmful action targeting ‘Us’. In other words, the passive structure, first, is triggered by OBL’s experiencing of harmful actions or signs of suffering, and, second, attests to the presence of expectations about the need to defend the ingroup, which ultimately serves the motivational function of framing (i.e. a call for counteraction). In contrast, in the active voice structure, the focus is on the harmer and on an opposing coalition against which ‘We’ need to maintain a strong coalition, which ultimately serves the prognostic function of framing (i.e. identifying the source of the conflict and who is responsible for ‘our’ unfavourable reality). That said, not only the use of voice but also the deployment of various mood types (as explored in next subsection) is found to be a critical resource to activate more framing functions and to present the status of an utterance as an action or an act of urging for an action, which provides support to Heritage’s (2012) contention in this regard.

Various forms of mood and their illocutionary points

Although the choice of the declarative mood type is predominant (see Examples 1 through 17)—which serves in building stereotypical images of outgroups—utterances in interrogative and imperative mood are also used to, respectively, convey questions that seek confirmation of a call for violence, and convey commands/directives. Regarding the interrogative mood, consider Example 19 where the interrogative form activates the structure of a rhetorical question that expects a ‘no’ answer, and the question thus counts as assertion-commissive. That is, through the interrogative structure, OBL not only commits himself to the truth of the propositional content that frames violence against ‘Others’ as being ‘self-defence’, but also promotes his undertaking and commitment to this ‘self-defence’ violent course of action and mobilises similar response against ‘the aggressor’. The rhetorical question, as such, marks OBL’s epistemic domain in relation to a collective threat and his framing of violence as a collective defence. This question also counts as trying to get the ingroup’s addressees to behave violently and to invite a match between their behaviours and the propositional content, that is, to self-defense against ‘Others’. In Heritage’s (2012) terms, the expected ‘no’ answer-interrogative serves to perceive the content as assertive rather than as questioning whether self-defence and punishing the aggressor is justified. That is, the interrogative is perceived as a positive assessment of ‘our’ violence to be agreed with (or confirmed) rather than a request for information. The question here “is fundamentally an attitude… It is an utterance that “craves” a verbal or other semiotic (e.g., a nod) response. The attitude is characterized by the [writer’s] subordinating himself to his [readers]” (Bolinger, 1957, p. 4) whose agreement and confirmation he is trying to win as a step towards mobilising and radicalising them to violence.

-

(19)

Is self-defence and punishing the aggressor in kind vilified terrorism? (OBL1)

In the imperative form of the act of othering, OBL, as in Example 20, communicates a request for action through a negative command (‘do not…’) that is aimed at getting the addressees to act in a way that ensures some disadvantage to ‘Others’ (i.e. the Americans, the “far enemy”, Miller, 2015, p. 12). By uttering and thus performing an illocutionary act of a directive point, OBL imposes a moral status of a person who is not scared of ‘Others’—which serves in presenting himself as a leader or someone who is aligned with the putative readers and is in a position of a demander of actions and of firm stances against the disaligned ‘Others’. These ‘Others’ and their role in attempting to ‘scare’ ‘Us’ with their ‘weapons’ have been backgrounded to emphasise the command function of the utterance while emphasizing the religious epistemic status of the informing or commanding person, as realized in the since-clause (underlined).

-

(20)

Do not let these thugs scare you with their weapons, since Allah has wasted their plots and weakened their might. (OBL2)

A clearer case of backgrounding the Americans, to emphasize the command or request for action, is expressed in Examples 21a and 21b which are however in declarative form. In these examples, the others’ role in invading ‘Our’ religious group members in Pakistan, Afghanistan and elsewhere is backgrounded for the purpose of amplifying the directive point (i.e. the inciting function) of the utterances against ‘Others’, as indicated by the performative verb, incite, underlined. Despite the declarative form of these utterances, their point is not assertive but directive; that is, OBL is not informing but requesting actions. In sum, the close analysis of the illocutionary point of OBL’s use of various mood types provides evidence of (i) his strategic activation of the prognostic framing function which implies the articulation of proposed solutions and (ii) his moral sanctioning of violence within the framework of loyalty to the ingroup and the framework of liberty/oppression and self-defence.

-

(21)

a. We incite our Muslim brothers in Pakistan to defend, with all that they possess and are capable of, against the American Crusader forces invading Pakistan and Afghanistan. (OBL7)

b. We do incite our brothers to fight you, stab you, and inflict a massacre in you. (OBL3)

Conclusion and further research

Othering is an ideological, social and discursive practice in which a language user strategically deploys particular grammatical choices whose patterns manifest and function—in Verschueren’s (2012, p. 2) terms—as a powerful tool for coercing into and legitimating aggressive attitudes, behaviours and negative consequences in terms of hostility and stereotyping. This study has explored the practice of othering through analysis of grammatical structure and its pragmatic functions, as realized in a set of texts communicated by OBL in the period following the 9/11 attacks. The analytical procedure showcased has the potential to aid in hate and threat assessment by sensitizing security threat assessors to the kind of linguistic resources used in othering as a premise for radicalisation to violence. The analysis has revealed how an extremist may construe allegedly “reasonable hostility” (Tracy, 2008, p. 169) in terms of attacking the public face of outgroups and inciting violence against them (Culpepper, 2011) within a moral struggle which an ingroup ought to resist. The findings contribute to threat assessors’ understanding of the relationship between language and sociopolitically aggravated acts of othering and antagonism, by addressing terrorist public statements as a site of “relatively durable set of [inter-group] social relations” (see also Bourdieu, 1991, p. 8; Malešević, 2019). The findings present the language of othering in terrorist discourse as being a code of social attitudes, relationships and obligations, where the writer is in a constant negotiation of intragroup links and inter-group relationship, and presents himself as a “deontic” participant in a deontic action (Searle, 2009, p. 9) of defending the ingroup’s ideological and physical territories, for the defence of which he also calls for a collective action. The findings support Searle’s (2009, p. 89) argument that utterances in a text promote a moral order and create “a reality of deontology. It is a reality that confers rights, responsibilities, and so on”. The findings also provide support to Van Langenhove’s (2017) argument that language users as agents in social structures have the deontic power to create, promote or negate some moral metavalues through contributing to our understanding of the link between agency and structure.

The argument on the role of syntax in the act of othering, in this paper, accords with other studies that have noted the value of syntactic features in the investigation of otherness (e.g. Pandey, 2004; Lams, 2018). These features have provided clues that can account for the strategic character of verbal aggression in othering texts and the moral underpinnings therein, particularly in circumstances of conflict and lack of security, where—in Suleiman’s (2006) terms—particular identities tend to become more salient and polarised. The findings show that it is not only a terrorist’s actions that can be aggressive but also their linguistically realized attitudes and acts of othering which involve acts of impoliteness. This finding accords with Janicki’s (2017) view of aggression which is inclusive of all kinds of phenomena such as behaviours, activities, situations, attitudes, and so on. This aggression can be accomplished by two main strategies of othering—overt othering, and covert othering—in which choices with respect to outgroup participants are directly or indirectly represented as agentive of ‘bad’ actions, and ingroup participants are represented as affected (i.e. acted-upon). This construction serves in establishing two opposing coalitions of distinct master identities, “expressed through the ideological us versus them binary opposition” (Thetela, 2001, p. 347). The various grammatical choices identified in terms of mood type, clause voice, and non/transactive construction have a potential to impact the addressees’ perception of outgroups which are seen as blameworthy and morally responsible for victimizing the ingroup and thus for ‘our’ reactive, defensive violence. While overt othering (in transactive construction, active voice, and only declarative mood) places increased emphasis on the perception of the agency of Others, covert othering (in nontransactive construction, passive voice, and any mood type) places more emphasis on the immoral actions. In Van Dijk’s (1998, p. 207) terms, this consistent construction of negative agentive role and negative action of outgroups’ acts within the victim/victimizer framework serves in constructing a “‘code for’ ideological positions”.

The findings have also provided evidence that syntactic choices have a potential to enact relational links metavalues (specifically, ingroup/loyalty, and authority/respect metavalues) and intergroup treatment metavalues (namely, liberty/oppression, and harm/care metavalues). The findings accord with previous work on moral metavalues enacted in terrorist contexts and emphasise the moral element in terrorism (e.g. Seto, 2002; Bandura, 2016; Etaywe and Zappavigna, 2021). Despite the heinous actions of an extremist, the moral reasonings underpinning the act of othering in the dataset have presented the construction of otherness as being morally engaged and intensely motivated by moral elements, supporting Hahn et al.‘s (2018) findings in this regard. In addition, the syntactic choices tend to activate particular framing functions (i.e. prognostic, diagnostic, and motivational): overt othering tends to stress the diagnostic framing while covert othering tends to emphasize the motivational framing. The functions of framing identified—in Smith’s (2018) terms—facilitate radicalisation to terrorism since they serve to sustain specific master identities and shared values while providing a diagnostic and prognostic for the constructed reality. The consideration of the illocutionary point of various mood forms, as well as the role of OBL’s epistemic status in the determination of whether an utterance is conveying information or requesting/demanding action, has offered clues to the language user’s personal identity and relational identity as being deeply intertwined with his epistemic status and the mood of his utterances. Though there appeared to be an association between mood type (e.g. declarative) and some illocutionary points (e.g. assertion or conveying information), this relationship has been found—as also argued by Heritage (2012)—not to be fixed. Utterances of declarative, imperative and interrogative forms tend to be of directive illocutionary point in the practice of othering within terrorism context, that is, they attempt to get the members of cultural/religious ingroup to behave violently, as a radicalising feature of discourse.

Since this paper does not claim that its description of the othering act is exhaustive or representative of othering in all terrorist contexts, future research might expand the examination of othering undertaken in this study to consider the kind of othering produced and the linguistic resources employed by terrorists from different ideological backgrounds. The same analytical procedures may also be extended to the study of the othering act in other contexts, such as news media and political discourse, that utilize otherness for various ideological purposes. That said, I hope that the approach showcased will provide a useful complementary method to the investigative approaches to understanding the language of aggression and conflict, which is crucial for maintaining peace, countering hate and preventing radicalisation to extremism worldwide.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Adams B, Brown A, Flear C, Thomson M (2011) Understanding the process of radicalisation: review of the empirical literature. Defence Research and Development Canada, Canada

Aijmer K (1996) Conversational routines in English: convention and creativity. Longman, London, New York, NY

Anthony L (2019) AntConc (Version 3.5.8) [Computer Software]. Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan

Bandura A (2016) Moral disengagement: how people do harm and live with themselves. Worth Publishers.

Benford R, Snow D (2000) Framing processes and social movements: an overview and assessment. Annu Rev Sociol 26:611–639

Bolinger D (1957) Interrogative structures of American English. University of Alabama Press, Tuscaloosa, AL

Bourdieu P (1991) Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Brown P, Levinson S (1978) Universals in language usage: politeness phenomena. In: Goody E (Ed.) Questions on politeness: strategies in social interaction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 56–289

Brown P, Levinson S (1987) Politeness: some universals in language usage. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Butler C (1988) Pragmatics and systemic linguistics. J Pragmat 12:83–102

Butt D, Lukin A, Matthiessen C (2004) Grammar—the first covert operation of war. Discourse Soc 15(2–3):267–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926504041020

Cap P (2017) The language of fear: communicating fear in public discourse. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Chiluwa I (2015) Radicalist discourse: a study of the stances of Nigeria’s Boko Haram and Somalia’s AlShabaab on Twitter. J Multicult Discourses 10(2):214–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17447143.2015.1041964

Crystal D (2008) A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics, 6th edn. Blackwell Publishing, USA

Culpeper J (2011) Impoliteness: using language to cause offence. Cambridge Unversity Press, Cambridge

Du Bois J (2007) The stance triangle. In: Englebretson R (ed) Stancetaking in discourse: subjectivity, evaluation, interaction. John Benjamins, Philadelphia, PA, pp. 139–182

Etaywe A, Zappavigna M (2021) Identity, ideology, and threatening communication: an investigation of patterns of attitude in terrorist discourse. J Lang Aggress Confl 10(2):75–110. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlac.00058.eta

Farkas J, Schou J, Neumayer C (2018) Platform antagonism: racist discourses on fake Muslim Facebook pages. Crit Discourse Stud https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2018.1450276

FBIS Report (2006) Compilation of Usama bin Laden statements 1994–January 2004. https://file.wikileaks.org/file/cia-fbis-bin-laden-statments-1994-2004.pdf. Accessed 15 Dec 2019.

Goffman E (1974) Frame analysis: an essay on the organization of experience. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Hahn L, Tamborini R, Novotny R, Grall C, Klebig B (2018) Applying moral foundations theory to identify terrorist group motivations. Political Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12525

Halliday MAK (1973) Explorations in the functions of language. Edward Arnold, London

Halliday MAK, Matthiessen C (2014) Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. Routledge, Oxon

Heritage J (2012) Epistemics in action: action formation and territories of knowledge. Res Lang Soc Interact 45(1):1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/08351813.2012.646684

Higgins C (2007) Constructing membership in the in-group: affiliation and resistance among urban Tanzanians. Pragmatics 17/1:49–70. https://doi.org/10.1075/prag.17.1.05higj

Holslag A (2015) The process of othering from the “social imaginaire” to physical acts: an anthropological approach. Genocide Stud Prev9(1):96–113. https://doi.org/10.5038/1911-9933.9.1.1290

Janicki K (2017) What is conflict? What is aggression? Are these challenging questions? J Lang Aggress Confl 5(1):156–166

Kádár D (2017) Politeness, impoliteness and ritual. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Kádár D, Parvaresh V, Ning P (2019) Morality, moral order, and language conflict and aggression. J Lang Aggress Confl 7(1):6–31. https://doi.org/10.1075/jlac.00017.kad

Khosrokhavar F (2014) Radicalisation. Maison des Sciences de l’Homme, Paris

Lams L (2017) Othering in Chinese official media narratives during diplomatic standoffs with the US and Japan. Palgrave Commun 3(33). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0034-z

Lams L (2018) Discursive constructions of the summer 2015 refugee crisis: a comparative analysis of French, Dutch, Belgian francophone and British centre-of-right press narratives. J Appl Journalism Media Stud 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1386/ajms.7.1.103_1

Leech G (1980) Language and tact. Amsterdam.

Leech G (1983) Principles of pragmatics. Longman, London

Leets L, Giles H (1997) Words as weapon: when do they wound? Investigations of harmful speech. Hum Commun Res 24(2):260–301

Lutz J, Lutz B (2008) Global terrorism. Routledge, London and New York, NY

Malešević S (2019) Cultural and anthropological approaches to the study of Terrorism. In: Chenoweth E, English R, Gofas A, Kalyvas S (eds) The Oxford handbook of terrorism. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 177–193

Mandel D (2010) Radicalization: what does it mean? In: Pick T, Speckhard A, Jacuch B (eds) Home-grown terrorism: understanding and addressing the root causes of radicalisation among groups with an immigrant heritage in Europe. IOS Press, Amsterdam, pp. 101–113

Martínez N (2013) Illocutionary constructions in English: cognitive motivation and linguistic realization. Peter Lang, Bern

Miller F (2015) The Audacious ascetic: what the bin Laden tapes reveal about al-Qa’ida. Hurst & Company, London

Min S (2008) Study on the differences of speech act of criticism in Chinese and English. US–China Foreign Lang 6(3):74–77

Muschalik J (2018) Threatening in English: a mixed method approach. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/Philadelphia

Pandey A (2004) Constructing otherness: a linguistic analysis of the politics of representation and exclusion in Freshmen writing.Issues Appl Linguist14(2):153–184

Parvaresh V (2019) Moral impoliteness. J Lang Aggress Confl 7(1):79–104

Pennebaker J, Chung C (2007) Computerized text analysis of al-Qaeda transcripts. In: Krippendorff K, Bock M (eds) A content analysis reader. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA

Perry B, Mason G (2018) Special edition: discourses of hate-guest editors’ introduction. Int J Crime Justice Soc Democr 7(2):1–3. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v7i2.521

Ray S (2017) A crusade gone wrong: George W. Bush and the war on terror in Asia. Int Stud 52(1-4):12–26

Reicher S, Haslam A, Rath R (2008) Making a virtue of evil: a five-step social identity model of the development of collective hate. Soc Person Psychol Compass 2/3(2008):1313–1344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00113.x

Searle J (1999) Mind, language and society. Basic Books, USA

Searle J (2009) Making the social world. The structure of civilization. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Seto T (2002) The morality of terrorism. Loyola Los Angel Law Rev 35:1272–1264

Shuy R (2010) Linguistics and terrorism cases. In: Coulthard M, Johnson A (eds) Routledge Handbook of Forensic Linguistics. Routledge, London, pp. 558–575

Shuy R (2020) Terrorism and forensic linguistics: Linguistics in terrorism cases. In: Coulthard M, May A, Sousa-Silva R (eds) The Routledge handbook of forensic linguistics. Wiley Blackwell, Chichester, pp. 445–462

Silva D(2017) The othering of Muslims: discourses of radicalization in the New York Times, 1969–2014 Sociol Forum 32(1):138–161. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12321

Silverstein M (1992) The uses and utility of ideology: some reflections. Pragmatics 2(3):311–323

Smith A (2018) How radicalization to terrorism occurs in the United States: what research sponsored by the National Institute of Justice tells us. National Institute of Justice, Washington

Smith B, Snow D, Fitzpatrick K, Damphousse K, Roberts P, Tan A (2016) Identity and framing theory, precursor activity, and the radicalization process. Final grant report to NIJ. Available via https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/249673.pdf

Spencer-Oatey H, Kádár D (2016) The bases of (im)politeness evaluations: Culture, the moral order and the East–West debate. East Asian Pragmat 1(1):73–106

Ståhl T, Zaal M, Skitka L (2016) Moralized rationality: relying on logic and evidence in the formation and evaluation of belief can be seen as a moral Issue. PLoS ONE 11(11):e0166332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166332

Straun J (2009) A linguistic turn of terrorism studies. DIIS Working Paper 2009:01. Retrieved from http://pure.diis.dk/ws/files/105548/WP2009_02_Linguistic_Terrorism.pdf

Suleiman S (2006) Constructing languages, constructing national identities. In: Omoniyi T, White G (eds) Sociolinguistics of identity. Continuum, London and New York, NY, pp. 50–71

Sykes M (1988) From “Right” to “Needs”: official discourse and the “welfarization” of race. In: Smitherman-Donaldson G, Van Dijk T (eds) Discourse and dscrimination. Wayne State University Press, Michigan, pp. 176–205

Thetela P (2001) Critique discourses and ideology in newspaper reports: a discourse analysis of the South African press reports on the 1998 SADC’s military intervention in Lesotho. Discourse Soc 12(3):347–370

Tracy K, Robles J (2002) Everyday talk: building and reflecting identities, 2nd edn. The Guildford Press, New York and London

Tracy K (2008) “Reasonable hostility”: situation-appropriate face-attack. Journal of Politeness Res: Lang Behav Cul 4(2):169–191. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPLR.2008.009

Van Dijk T (1998) Ideology: a multidisciplinary approach. Sage Publications, London/ California/ New Delhi

Van Leeuwen T (1996) The representation of social actors. In: Caldas-Coulthard C, Coulthard M (eds) Texts and practices: reading in critical discourse analysis. Routledge, London & New York, NY, pp. 32–70

Van Leeuwen T (2007) Legitimation in discourse and communication. Discourse Commun 1(1):91–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481307071986

Van Langenhove L (2017) Varieties of moral orders and the dual structure of society: a perspective from Positioning Theory. Front Sociol 2(9) https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2017.00009

Verschueren J (2009) Introduction: the pragmatic perspective. In: Verschueren J, Östman J (eds) Key notions for pragmatics. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam, pp. 1–27

Verschueren J (2012) Ideology in language use: pragmatic guidelines for empirical research. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge and New York, NY

White P (2006) Evaluative semantics and ideological positioning in journalistic discourse. In: Lassen I (ed) Mediating ideology in text and image: ten critical studies. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 37–69