Abstract

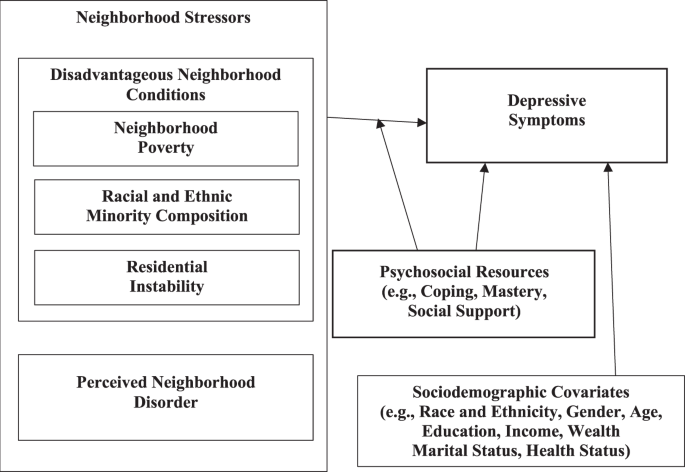

This study synthesizes the current theoretical knowledge to explain the relationship between neighbourhood stressors and depressive symptoms. The two most relevant sociological theories, social disorganization theory and stress process theory, are identified. The current study carefully reviewed the two theories regarding their historical development and key conceptual aspects, beginning with the theoretical evolution of research on neighbourhood stressors and mental health. This study also provides detailed critiques on each theory and suggests how researchers can apply both theories to their empirical testing. For example, social disorganization theory points out the application of both objective and subjective aspects of neighbourhood stressors. Also, the stress process theory emphasizes the mediating or moderating role of psychosocial resources. In conclusion, this study suggests a conceptual model of neighbourhood stressors, psychosocial resources, and depressive symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Theoretical evolution of research on neighbourhood stressors and mental health

From the beginnings of modern sociological research, living in disadvantaged neighbourhoods has been thought to escalate the possibility of mental health problems (Durkheim, 1897/1951; Faris and Dunham, 1939; Simmel, 1903/1950; Wirth, 1938). Durkheim (1897/1951) theorized that suicide rates should be explained by social facts—the extent to which the moral forces of communal life structure us. Durkheim’s research on suicide initiated exploring associations between individual mental health and social environments, including neighbourhoods. This theoretical exploration of neighbourhood effects has coincided with urbanization (Park, 1915; Burgess, 1925; Wirth, 1938). Both Simmel (1903/1950) and Wirth (1938) pointed out that urban neighbourhoods could be more detrimental to mental health than rural neighbourhoods due to bigger geographic size, higher population density, and heterogeneity of residents. In that sense, the current study synthesized the theoretical evolution of research on neighbourhood effects on mental health in urban settings.

As one of the early studies in this theoretical tradition, Faris and Dunham (1939) demonstrated that neighbourhoods with higher social disorganization have disproportionately higher rates of hospitalization for mental disorders than other areas. In particular, Faris and Dunham (1939) showed that schizophrenic patients tended to be socially isolated in urban Chicago neighbourhoods characterized by concentrated poverty, high proportions of foreign-born residents, and rapid population turnover. They also reported that few residents knew each other or built lasting social ties to these neighbourhoods. Thus, they concluded schizophrenia was affected by excessive social isolation due to the social disorganization of the neighbourhoods. This seminal research has stimulated a stream of multidisciplinary studies, specifically focusing on the implications of community-level poverty and other disadvantages of local physical and social environments (Elliott et al., 1996). Following these seminal studies’ tradition, social disorganization theory has been applied to explain neighbourhood effects on mental health outcomes (Shaw and McKay, 1942).

Social disorganization theory

Historical development of social disorganization theory

Social disorganization is conceptualized as “the inability of a community structure to realize the common values of its residents and maintain effective social controls” (Sampson and Groves, 1989, p. 777). This conceptualization implies a process whereby neighbourhood characteristics make the realization of “common values” and the maintenance of “social controls”. In this way, the social disorganization of a neighbourhood could be used as an underlying process to explain the influences of disadvantageous neighbourhood characteristics on mental health, including neighbourhood poverty and residential instability. For example, a neighbourhood with high poverty rates might not motivate its residents to establish appropriate social norms.

In addition to Durkheim (1897/1951), Faris and Dunham (1939) were among the first to associate social disorganization with mental health outcomes at the neighbourhood level, suggesting that socially disorganized areas increase social isolation, as social support was harder to develop and maintain. Almost in the same period, focusing on delinquency, Shaw and McKay (1942) developed the concept of social disorganization. They provided the first general theoretical framework for understanding how neighbourhoods influenced a broad range of outcomes, including mental health. More specifically, they argued that three neighbourhood characteristics—“economic status,” “population composition” (racial/ethnic composition) and “physical status” (population increase or decrease)—could be associated with the social disorganization of neighbourhoods which, in turn, were related to individual outcomes (Shaw and McKay, 1942, p. 136).

Shaw and McKay’s research followed the human ecological perspective on neighbourhood processes (Park, 1915; Burgess, 1925). The human ecological perspective had seen urban neighbourhoods as the products of natural processes of selection and competition. Shaw and McKay (1942) observed higher rates of negative outcomes (e.g., crime) persisted in the same neighbourhoods, regardless of the movement of different populations through them (Sampson, 2003). From these findings, the early twentieth century sociologists began to theorize that neighbourhoods produced enduring adverse effects on various outcomes (Sampson, 2012).

Social disorganization theory did not go unchallenged, however. The initial formulation of this theory experienced some problems of conceptualization and operationalization. A fundamental problem was with the definition of social disorganization since Shaw and McKay (1942) did not explicitly distinguish the anticipated results of social disorganization (i.e., increased rates of delinquents) with social disorganization itself (Bursik, 1988). For example, the neighbourhood crime rate could be both an example of social disorganization and an outcome caused by social disorganization. Later, this issue was successfully addressed when researchers attempted to provide a clear conceptual and operational definition of social disorganization (Kornhauser, 1978; Sampson and Groves, 1989). Since then, social disorganization theory has frequently been applied to explain the harmful effects of neighbourhood characteristics on individual outcomes, including mental health.

Social disorganization theory is about between-neighbourhood differences in the breakdown of the structure of social values and relations (Kornhauser, 1978). These neighbourhood characteristics can be expressed as objective and subjective indicators. Following the tradition of previous studies, this study labels the objective indicators as disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions and the subjective indicators as perceived neighbourhood disorders. Social disorganization theory explains how disadvantageous characteristics of neighbourhoods make a stressful environment by obstructing the development of formal (e.g., organizational participation) and informal (e.g., friendship network) ties that are necessary to solve common problems (Sampson and Groves, 1989; Sampson et al., 1997).

For example, neighbourhood-level economic status is a powerful determinant of organizational participation. Neighbourhoods with low economic status have a weaker organizational base than areas with higher economic status (Kornhauser, 1978). Also, the heterogeneity of the racial/ethnic composition of neighbourhoods may undermine communication between neighbours, limiting their ability to solve commonly experienced problems (Elliott et al., 1996; Halpern, 1993; Kubrin, 2009). Conversely, sometimes the homogeneity of racial/ethnic composition of neighbourhoods may not benefit social organization, especially in a racially segregated urban downtown area (Wilson, 1987). Residential instability may have harmful effects on the development of adequate friendship and kinship networks as well as local associational ties since social relationships and shared understandings must then be reconstructed (Manturuk, 2012). Residents in socially disorganized neighbourhoods may also perceive these conditions as stressful environments (Matheson et al., 2006; Ross et al., 2000). Consequently, this study suggests that researchers can apply the social disorganization theory to incorporate objective and subjective neighbourhood stressors as key predictors.

Social disorganization theory and depressive symptoms

This study suggests that higher disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions will be associated with higher depressive symptoms from the review of social disorganization theory. Many existing studies showed compelling evidence that disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions were positively associated with depressive symptoms (e.g., Latkin and Curry, 2003; Ross, 2000). Although the relationship between social disorganization and depressive symptomatology could be bidirectional or even a vicious cycle, this study recommends that researchers set disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions and perceived neighbourhood disorder as key predictors reflecting the neighbourhoods’ social disorganization.

Critique of social disorganization theory

Social disorganization theory has several strengths regarding the characteristics of a good theory defined by Jaccard and Jacoby (2020). Two major strengths of social disorganization theory are its utility and logical consistency in identifying neighbourhoods’ structural characteristics that generate stressful environments. Disadvantaged areas are projected to have high depressive symptoms, especially for more socioeconomically vulnerable populations with limited mobility. Thus, social disorganization theory explains why depressive symptoms may not be randomly distributed across neighbourhoods. Also, the empirical testability of social disorganization theory is relatively high, given that its key components, such as both objective and subjective indicators, are now amenable for empirical testing. Sampson and Groves (1989) pointed out that no previous researchers had directly tested this theory because the empirical test required extensive data measuring key neighbourhood-level structural factors within the theory. However, recent efforts have made accessible and appropriate datasets to test this theory, such as data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighbourhoods (Sampson, 2012).

Further, an additional strength of social disorganization theory is its applicability to urban neighbourhoods, in that its theoretical development has been under the tradition of urban studies, as explained above. As urban neighbourhoods continue to grow, social disorganization theory may evolve to better reflect the urban neighbourhoods (Fitzpatrick and LaGory, 2011). Urban settings are especially suited for studying social disorganization theory due to their unique characteristic of more sociodemographically concentrated environments than other geographic locations.

Nevertheless, social disorganization theory tends to focus narrowly on the negative aspects of disadvantaged neighbourhoods. This theory overlooks the positive elements of underprivileged areas, such as attachment to community and social support (Jacobs, 1961). Low-income residents in disadvantaged inner-city neighbourhoods support each other by “highly organized, cohesive networks of family and friends” (Jackson et al., 2009, p. 967). Stack (1974) concluded that residents “have evolved patterns of co-residence, kinship-based exchange networks,” maintaining “strong loyalties to their kin” (p. 124). Therefore, social disorganization theory underestimates the positive effects of community-level support on residents’ mental health in disadvantaged neighbourhoods.

Furthermore, social disorganization theory does not adequately address how these disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions affect individual mental health. Social disorganization theory does not elaborate on the mechanisms by which disadvantaged structures are realized in individual lives (Thoits, 2010). Although social disorganization theory emphasizes the roles of formal and informal social ties and social control, the theoretical explanation for these factors’ effects on depressive symptoms has been overlooked. Thus far, social disorganization theory does not provide a sophisticated process of how stressful neighbourhood environments affect depressive symptoms.

Stress process theory

Historical development of stress process theory

Faris and Dunham’s (1939) research has also inspired many successive researchers (e.g., Dohrenwend and Dohrenwend, 1969; Hollingshead and Redlich, 1958; Kawachi and Berkman, 2003; Silver et al., 2002). This research has grown into what today is a dominant theory in the social determinants of mental health: stress process theory. Pearlin and colleagues first used the concept of the stress process (Pearlin et al., 1981). They originally formulated the stress process theory with life events (e.g., disruptive job events) as exemplary stress sources. Later, stress researchers introduced other sources of stress, such as (a) chronic strains (more enduring or repeated life problems), (b) non-events (desired or anticipated but not occurring events), (c) traumas (stressors of overwhelming severity), and (d) daily hassles (Avison and Turner, 1988; Pearlin, 1989; Turner and Lloyd, 1995; Wheaton, 1994). In that sense, neighbourhood stressors have been viewed as chronic strains on residents. They affect inhabitants’ daily lives in a chronic and recurring fashion; however, they are more fundamental stress sources than daily hassles (Pearlin, 1989; Thoits, 2010).

At an early stage, the stress process theory application focused on individual-level stressors (Aneshensel, 2010; Thoits, 2010). However, Pearlin (1989) recognized the importance of social contexts and labelled them as ambient strains that “are not attributable to a specific role but, rather, are diffuse in nature and have a variety of sources” (Avison and Comeau, 2013, p. 545). Pearlin (1989) began to be interested in neighbourhoods as distinctive social contexts that could give rise to their own distinctive stressors, such as uncertainty about personal safety and detrimental conditions of neighbourhood surroundings (Pearlin, 1999; Pearlin and Skaff, 1995). These neighbourhood-level chronic stressors can be exacerbated when residents, especially those from low-income households, see themselves inescapably bound to disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions (Pearlin, 1999). Wheaton and Clarke (2003) also applied stress process theory to neighbourhood-level social inequality, conceptualizing this inequality as one of the multiple layers of social hierarchy. Since then, stress process theory has “commonly been utilized as a way to theorize linkages between place and people—thereby situating micro-level experiences of an individual within the meso-level social context of neighbourhoods” (Carpiano, 2014, p. 109).

Stress process theory and depressive symptoms

Stress process theory can describe the mediating mechanisms through which neighbourhood stressors affect depressive symptoms or the mechanisms that moderate the effects of neighbourhood stressors on depressive symptoms (Aneshensel, 2010; Thoits, 2010; Turney et al., 2012). As mentioned earlier, disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions can be viewed as chronic stressors (Pearlin, 1989). Neighbourhood stressors may be primary stressors in a sequence of stress proliferation, the process through which a primary stressor has negative consequences for mental health (Pearlin et al., 1997). Primary stressors can be either objective or subjective (Pearlin et al., 1990). Therefore, both disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions and perceived neighbourhood disorder can be conceptualized as primary stressors, one of which is objective, and the other is subjective.

Furthermore, stress process theory focuses on the roles of psychosocial resources that alter (i.e., moderate) or explain (i.e., mediate) the effects of stress exposure on depressive symptoms (Pearlin et al., 1981). Such resources play a crucial role in clarifying why individuals exposed to the same stressors may experience different outcomes. Pearlin (1999) provided some examples of these mediating or moderating resources: (a) individual coping behaviours, (b) social support, and (c) perceived mastery over life. The mechanisms of the stress process occur within the social dimension of a neighbourhood where disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions create differential exposure to stress for its residents (Aneshensel, 2010). Psychosocial resources can either mediate or moderate the relationship between primary stressors and mental health outcomes.

Critique of stress process theory

Many stressful experiences “can be traced back to surrounding social structures and people’s locations within them” (Pearlin, 1989, p. 242). The stress process theory’s major strength is that it bridges the gap between neighbourhood-level structures and individual-level experiences. It explains how structured risk factors, as stressful experiences, become actualized in the lives of individuals. Conjointly, stress process theory has uniquely focused on the mediating or moderating roles of psychosocial resources from its development (Pearlin, 1999). Another key strength of the stress process theory is its utility in explaining the sociological origins of mental health disparities (Aneshensel, 2009). This theory explains why exposure to stressors, access to psychosocial resources, and outcomes may differ among diverse populations. Also, the stress process theory has high testability. For empirical researchers, it is not hard to test this theory, given that it illustrates key components (primary stressors, psychosocial resources, mental health outcomes) and shows the possible pathways between them quite logically.

However, as already discussed, earlier stress process theorists and researchers in the 1980s did not pay much attention to the influences of neighbourhood stressors on the social distribution of mental health outcomes (Cutrona et al., 2006; Thoits, 2010). This lack of attention is unexpected given that the origins of stress process theory lie in Faris and Dunham’s (1939) study linking social disorganization with mental health at the neighbourhood level (Silver et al., 2002). Instead, these early researchers measured individual characteristics as a proxy for the characteristics of the neighbourhood where they lived (Dohrenwend, 1990, 2000). Even though individual-level and neighbourhood-level characteristics can be correlated, a resident’s neighbourhood’s social conditions cannot be entirely decided by their individual characteristics (Aneshensel, 2010; South and Crowder, 1997). Moreover, previous studies consistently reported that—even when controlling for individual-level disadvantages—individuals who lived in disadvantaged neighbourhoods were “significantly more likely to experience negative outcomes” (Silver et al., 2002, p. 1458; see also Dohrenwend et al., 1992; Ross, 2000; Turner et al., 1995; Wheaton, 1978). Therefore, this lack of consideration of neighbourhood factors was a weak point in the early formulation of the stress process theory. Later, however, Pearlin (1999) and Aneshensel (2010) paid more attention to neighbourhood effects and incorporated the neighbourhood into the stress process model.

In addition, the stress process theory has some limitations in terms of parsimony. This theory involves a relatively high degree of complexity because it integrates mediating or moderating effects of psychosocial resources into its process. Explaining the roles of these resources, Pearlin (1999) acknowledged that these resources could function as either mediators or moderators. Initially, at the conceptual level, he introduced three psychosocial resources—coping, social support, and mastery—as moderating resources “having the capacity to hinder, prevent, or cushion the development of the stress process and its outcomes”. However, on the very same page, he mentioned that these resources “could as plausibly be regarded as mediating conditions, where the effects of the other components of the stress process on outcomes are channelled through the resources” (Pearlin, 1999, p. 405).

Conclusion: a conceptual model applying the two theories

Considering each theory’s fundamental weaknesses, this study concludes that researchers need to apply both social disorganization theory and stress process theory to identify the neighbourhood stressors associated with depressive symptoms. Figure 1 shows a conceptual model of neighbourhood stressors, psychosocial resources, and depressive symptoms. Each theory uniquely contributes to explaining the effects of neighbourhood stressors on depressive symptoms. First, social disorganization theory introduces disadvantageous neighbourhood characteristics (neighbourhood poverty, racial and ethnic composition, and residential instability) and perceived neighbourhood disorder, which is associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Another unique contribution of social disorganization theory is its applicability to urban settings. Although the recent application of stress process theory incorporated the concept of neighbourhood stressors, social disorganization theory is still needed because it provides the theoretical basis for choosing the most relevant indicators of neighbourhood stressors. These primary stressors (disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions and perceived neighbourhood disorder) are hypothesized to lead to higher depressive symptoms. Second, stress process theory is used to explain the mechanisms through which disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions affect depressive symptoms (i.e., mediation) or the mechanisms that exacerbate or buffer the effects of disadvantageous neighbourhood conditions on depressive symptoms (i.e., moderation).

As mentioned previously, a psychosocial resource can be examined as a moderator. There is a theoretical potential for the psychosocial resource to buffer or protect individuals from the adverse effects of neighbourhood stressors on the individuals’ mental health. Cohen and Wills (1985) argued that the stress-buffering effect of social support was identified “when the social support measure assesses the perceived availability of interpersonal resources that are responsive to the needs elicited by stressful events” (p. 310). The current study suggests that researchers can use individuals’ availability of resources from multiple interpersonal sources (e.g., spouse/partner, children, relatives, friends). Focusing on the psychosocial resource as a moderator is consistent with much of the research applying the stress process model. For example, Pearlin and Bierman (2013) contended that “Although resources may be seen as having the potential either to explain or to modify the effects of stress, we shall be concerned mainly with their ability to constrain the stressful consequences of stressors” (p. 330).

This study considers implications for the development of future theory and research. Whether applying both social disorganization theory and stress process theory can lead to unique insights remains to be seen in future research. Future studies can test the conclusion that applying both theories would be empirically beneficial. More specifically, a future study can test (a) the anticipated relationships between neighbourhood stressors (e.g., neighborhood poverty, racial and ethnic minority composition, and residential instability) and depressive symptoms and (b) the stress-buffering effects of psychosocial resources (e.g., coping, mastery, and social support) on the relationships.

References

Aneshensel CS (2009) Toward explaining mental health disparities. J Health Soc Behav 50(4):377–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000401

Aneshensel CS (2010) Neighbourhood as a social context of the stress process. In: Avison WR, Aneshensel CS, Schieman S, Wheaton B (eds) Advances in the conceptualization of the stress process: Essays in honor of Leonard I. Pearlin. Springer, New York, pp. 35–52

Avison WR, Comeau J (2013) The impact of mental illness on the family. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, Bierman A (eds) Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Springer, Netherlands, pp. 543–561

Avison WR, Turner RJ (1988) Stressful life events and depressive symptoms: disaggregating the effects of acute stressors and chronic strains. J Health Soc Behav 29(3):253–264. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137036

Burgess EW (1925) The growth of the city: an introduction to a research project. In: Park RE, Burgess EW, McKenzie RD (eds) The city. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 47–62

Bursik RJ (1988) Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: problems and prospects. Criminology 26(4):519–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.1988.tb00854.x

Carpiano RM (2014) The neighborhood and mental life: past, present, and future sociological directions in studying community context and mental health. In: Johnson RJ, Turner RJ, Link BG (eds) Sociology of mental health: selected topics from forty years 1970s–2010s. Springer, pp. 101–123

Cohen S, Wills TA (1985) Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 98(2):310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310

Cutrona CE, Wallace G, Wesner KA (2006) Neighborhood characteristics and depression: an examination of stress processes. Curr Dir Psychol Sci 15(4):188–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00433.x

Dohrenwend BP(1990) Socioeconomic status (SES) and psychiatric disorders: are the issues still compelling? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 25(1):41–47. https://europepmc.org/article/med/2406949

Dohrenwend BP (2000) The role of adversity and stress in psychopathology: Some evidence and its implications for theory and research. J Health Soc Behav 41(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676357

Dohrenwend BP, Dohrenwend BS (1969) Social status and psychological disorder: a causal inquiry. Wiley, New York

Dohrenwend BP, Levan I, Shrout PE, Schwartz S, Naveh G, Link BG, Skodol AE, Stueve A (1992) Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue. Science 255(5047):946–952. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1546291

Durkheim E (1897) Le suicide. Alcan, Lyon, English edition: Durkheim E (1951) Suicide (trans: Spaulding JA, Simpson G). Routledge, London

Elliott DS, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliott A, Rankin B (1996) The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. J Res Crime Delinq 33(4):389–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022427896033004002

Faris REL, Dunham HW (1939) Mental disorders in urban areas: an ecological study of schizophrenia and other psychoses. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Fitzpatrick K, LaGory M (2011) Unhealthy cities: poverty, race, and place in America. Routledge, New York

Halpern D (1993) Minorities and mental health. Soc Sci Med 36(5):597–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90056-A

Hollingshead AB, Redlich FC (1958) Social class and mental illness: a community study. Wiley, New York

Jaccard J, Jacoby J (2020) Theory construction and model-building skills: a practical guide for social scientists, 2nd edn. Guilford Press, New York

Jackson L, Langille L, Lyons R, Hughes J, Martin D, Winstanley V (2009) Does moving from a high-poverty to lower-poverty neighborhood improve mental health? A realist review of ‘Moving to Opportunity. Health Place 15:961–970. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.03.003

Jacobs J (1961) The death and life of great American cities. Random House, New York

Kawachi I, Berkman LF (eds) (2003) Neighborhoods and health. Oxford University Press, New York

Kornhauser RR (1978) Social sources of delinquency: an appraisal of analytic models. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Kubrin CE (2009) Social disorganization theory: then, now, and in the future. In: Krohn MD, Lizotte AJ, Hall GP (eds) Handbook on crime and deviance. Springer, New York, pp. 225–236

Latkin CA, Curry AD (2003) Stressful neighborhoods and depression: a prospective study of the impact of neighborhood disorder. J Health Soc Behav 44(1):34–44. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519814

Manturuk KR (2012) Urban homeownership and mental health: mediating effect of perceived sense of control. City Community 11(4):409–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6040.2012.01415.x

Matheson FI, Moineddin R, Dunn JR, Creatore MI, Gozdyra P, Glazier RH (2006) Urban neighborhoods, chronic stress, gender and depression. Soc Sci Med 63(10):2604–2616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.001

Park RE (1915) The city: suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the city environment. Am J Soc 20(5):577–612. https://doi.org/10.1086/212433

Pearlin LI (1989) The sociological study of stress. J Health Soc Behav 30(3):241–256. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136956

Pearlin LI (1999) The stress process revisited: reflections on concepts and their interrelationships. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC (eds) Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp. 395–415

Pearlin LI, Aneshensel CS, LeBlanc AJ (1997) The forms and mechanisms of stress proliferation: the case of AIDS caregivers. J Health Soc Behav 38(3):223–236. https://doi.org/10.2307/2955368

Pearlin LI, Bierman A (2013) Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC (eds) Handbook of the sociology of mental health. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, pp. 325–340

Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT (1981) The stress process. J Health Soc Behav 22(4):337–356. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136676

Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM (1990) Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist 30(5):583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

Pearlin LI, Skaff MM (1995) Stressors and adaptation in late life. In: Gatz M (ed) Emerging issues in mental health and aging. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp. 97–123.

Ross CE (2000) Neighborhood disadvantage and adult depression. J Health Soc Behav 41(2):177–187. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676304

Ross CE, Reynolds JR, Geis KJ (2000) The contingent meaning of neighborhood stability for residents’ psychological well-being. Am Soc Rev 65(4):581–597. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657384

Sampson RJ (2003) Neighborhood-level context and health: lessons from sociology. In: Kawachi I, Berkman LF (eds) Neighborhoods and health. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 132–146

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American city: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sampson RJ, Groves WB (1989) Community structure and crime: Testing social-disorganization theory. Am J Soc 94(4):774–802. https://doi.org/10.1086/229068

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277(5328):918–924. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.277.5328.918

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1942) Juvenile delinquency and urban area. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Silver E, Mulvey EP, Swanson JW (2002) Neighborhood structural characteristics and mental disorder: Faris and Dunham revisited. Soc Sci Med 55(8):1457–1470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00266-0

Simmel G (1903) Die Großstädte und das Geistesleben. Petermann, Dresden. English edition: Simmel G (1950) The metropolis and mental life (trans: Wolff K). Free Press, New York

South SJ, Crowder KD (1997) Escaping distressed neighborhoods: individual, community, and metropolitan influences. Am J Soc 102(4):1040–1084. https://doi.org/10.1086/231039

Stack CB (1974) All our kin: strategies for survival in a black community. Basic Books, New York

Thoits PA (2010) Sociological approaches to mental illness. In: Scheid TL, Brown TN (eds) A handbook for the study of mental health: social contexts, theories, and systems. Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 106–124

Turner RJ, Lloyd DA (1995) Lifetime traumas and mental health: the significance of cumulative adversity. J Health Soc Behav 36(4):360–376. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137325

Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA (1995) The epidemiology of social stress. Am Soc Rev 60(1):104–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096348

Turney K, Kissane R, Edin K (2012) After moving to opportunity: how moving to a low-poverty neighborhood improves mental health among African American women. Soc Ment Health 3(1):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869312464789

Wheaton B (1978) The sociogenesis of psychological disorder: reexamining the causal issues with longitudinal data. Am Soc Rev 43(3):383–403. https://doi.org/10.2307/2094497

Wheaton B (1994) Sampling the stress universe. In: Avison WR, Gotlib IH (eds) Stress and mental health: contemporary issues and prospects for the future. Plenum Press, New York, pp. 77–114

Wheaton B, Clarke P (2003) Space meets time: integrating temporal and contextual influences on mental health in early adulthood. Am Soc Rev 68(5):680–706. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519758

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wirth L (1938) Urbanism as a way of life. Am J Soc 44(1):1–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/217913

Acknowledgements

This paper is reconceptualized from a part of my doctoral dissertation, Relationships Between Neighborhood Stressors and Depressive Symptoms: The Moderating Effects of Social Support Among Older Adults. I especially appreciate Aloen L. Townsend, who advised my dissertation. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cho, S. Theories explaining the relationship between neighbourhood stressors and depressive symptoms. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 10 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-01014-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-01014-2