Abstract

The Covid-19 pandemic is primarily viewed as a threat to physical health, and therefore, biomedical sciences have become an integral part of the public discourse guiding policy decisions. Nonetheless, the pandemic and the measures implemented have an impact on the population’s psychosocial health. The impact of Covid-19 on the psychosocial care system should be thoroughly investigated to mitigate this effect. In this context, the present study was conducted to establish a consensus about the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial health and the care system in Belgium. Using the Belgian Superior Health Council’s expert database, a three-round Delphi consensus development process was organized with psychosocial experts (i.e., professionals, patients, and informal caregiver representatives). Overall, 113 of the 148 experts who participated in round 1 fully completed round 2 (76% response rate). Consensus (defined as >70% agreement and an interquartile interval (IQR) of no more than 2) was reached in round 2 for all but three statements. Fifty experts responded to round 3 by providing some final nuances, but none of them reaffirmed their positions or added new points to the discussion (44.25% response rate). The most robust agreement (>80%) was found for three statements: the pandemic has increased social inequalities in society, which increase the risk of long-term psychosocial problems; the fear of contamination creates a constant mental strain on the population, wearing people out; and there is a lack of strategic vision about psychosocial care and an underestimation of the importance of psychosocial health in society. Our findings show that experts believe the psychosocial impact of Covid-19 is underappreciated, which has a negative impact on psychosocial care in Belgium. Several unmet needs were identified, but so were helpful resources and barriers. The Delphi study’s overarching conclusion is that the pandemic does not affect society as a whole in the same way or with the same intensity. The experts, thereby, warn that the psychosocial inequalities in society are on the rise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Following China’s initial indications in 2019, Covid-19 spread worldwide to the majority of the countries, including Belgium. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared Covid-19 a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on January 30, 2021. Consequently, it became the first major contagious outbreak of this magnitude in the twenty-first century. Covid-19 was not only a highly infectious and lethal disease, but it was also sweeping the globe, necessitating drastic measures to keep the disease from spreading. Consequently, the current pandemic has been approached and defined primarily as a threat to physical health, with the biomedical and hard sciences now constituting the discourse guiding policy decisions regarding this public health challenge.

A biomedical dominance is understandable, especially in the immediate and acute aftermath of a contagious outbreak, because health systems must prioritize critical patient care and pathogen reduction. However, pandemics, particularly chronic pandemics such as Covid-19, necessitate the consideration of both biomedical and psychosocial aspects for society to successfully deal with the challenges at hand. Nonetheless, as Brewin et al. (2020) demonstrate, the psychosocial dimension is missing in official pandemic plans worldwide, which are primarily concerned with the pandemic’s biomedical implications. Psychosocial health appears to lack the sophisticated planning and governance arrangements that guide emergency interventions for physical injury and infection. However, previous contagious outbreaks and mounting evidence from Covid-19 are urging governments to recognize the importance of a solid biopsychosocial approach, in which biomedical and psychosocial aspects are deemed equally important in dealing with a pandemic (Cullen et al., 2020; Stuart et al., 2020; Wainwright and Low, 2020).

There are numerous reasons to support this claim. To begin, psychosocial health, in conjunction with the socioeconomic and cultural context in which people live, has a direct impact on the potential to adhere to control measures and proscribed hygiene behavior, directly influencing the outcome of an outbreak itself (IASC, 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; WHO, 2020). Experiencing a pandemic in the vast countryside, where you can still go for walks and have some freedom, is not the same as experiencing it in a city, where public and private spaces are more limited. Second, the impact of a contagious outbreak like Covid-19 on the population’s psychosocial health, particularly that of more vulnerable subgroups, is expected to be significant. The vast encounter with severe illness and death, mostly untimely and unexpected deaths in the case of Covid-19, is linked to a variety of long-term adverse psychological effects (Walsh, 2007). Furthermore, the implementation of protective measures to prevent the spread of the virus directly impacts the mental and social health of those involved. The chronicity of the measures taken to keep the pathogen from spreading within a population, in particular, places an ongoing strain on the society’s resilience, resulting in significant direct (e.g. anxiety, stress, etc.) and indirect (e.g. financial burden, loneliness, etc.) psychosocial effects on the population. As Campion (2020) points out, early detection of psychosocial needs in the population, particularly within vulnerable target groups, can aid in the operationalization of actions required to alleviate psychosocial symptoms before they become problematic. It is, therefore, beneficial to develop a biopsychosocial model from the start when dealing with a pandemic like Covid-19.

While there is a growing theoretical consensus among academics and even governments about the importance of a biopsychosocial approach in pandemic management, less attention is being paid to the facilitation of effective remediation of the pandemic’s psychosocial impact through the psychosocial care system and the impact of Covid-19 on the psychosocial care system itself. There are reasons to expect a significant impact at this system level as well because the current Covid-19 pandemic and the measures taken to control it have a profound effect on the organization of the healthcare system in general. This is already a well-known fact in the biomedical healthcare system. Because of concerns about overcrowding in intensive care units, hospital wards around the world have partially closed and reallocated their facilities and personnel to critical care settings. In June 2020, the WHO reported that staff was reassigned from non-covid to covid-related services in 92 percent of the 155 responding countries. This shift primarily impacted rehabilitation and chronic care, and it also impacted cancer treatment and acute cardiovascular care (WHO, 2020). Students, inactive employees, and retired personnel were also mobilized to increase the supply of healthcare workers in clinical settings (OECD, 2020). This impact, however, was not limited to the hospital setting. According to research, general practitioners and other primary care professionals believe that acute care in the first line is jeopardized, both because of their shift in focus during covid and because their patients consult them less frequently for non-covid problems (Gray and Sanders, 2020; Rawaf et al., 2020; Verhoeven et al., 2020). The long-term consequences of this impact are still unclear, but as Czeisler et al. (2020) have shown, delaying or avoiding medical care will likely increase morbidity and even mortality associated with both chronic and acute health conditions. Several papers have suggested that the psychosocial care system and its continuity were also impacted by Covid-19, an effect that was exacerbated by the preventive measures taken to keep the pathogen from spreading and the dominance of the biomedical discourse in policy decisions (Bojdani et al., 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Chevance et al., 2020). However, compared to biomedical aspects of health care, little is known about the precise impact and consequences.

The goal of this study, formulated in close collaboration with the mental health expert group of the Superior Health Council of Belgium, is to investigate the impact of Covid-19 on mental health and determine the pandemic’s impact on the psychosocial care system in Belgium. More broadly, this research will advance scientific understanding of the following research questions: how do the Covid-19 pandemic, and the primarily biomedically oriented policy decisions made, influence the daily practice of psychosocial care professionals, the services they provide, and how this all affects the people who use those services (i.e., patients and their informal caregivers). This knowledge can help preserve or enhance psychosocial remediation capacities, which are required within a biopsychosocial pandemic approach. To answer these research questions, a consultation of psychosocial professionals, patient representatives, and informal caregivers was organized in the context of a Delphi method of consensus development research setting.

Method

Study design

The Delphi method, first developed by the Rand Corporation in the 1950s, is a systematic and interactive research procedure that allows obtaining the opinion of a panel of independent experts on a specific subject. It is an iterative research method for structuring a group communication process to facilitate a group of individuals, as a whole, to deal with a complex problem (Linstone and Turoff, 2002). Therefore, the Delphi technique has proven to be an adequate technique for structuring and organizing group communication. Although there are various forms of Delphi, the method is most commonly known to be used in situations where a group consensus is sought (Steinert, 2009; Diamond et al., 2014). The same is also the case for this article.

The Delphi technique is beneficial for answering questions that cannot be answered using experimental or epidemiological methods (Jorm, 2015). The technique has been used for a wide range of purposes, including psychosocial research (De Meyrick, 2003). Because research and data on the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial care in Belgium still lacked at the time of this study, a Delphi research with psychosocial experts (i.e., professionals, patients, and informal caregivers) was deemed valuable and appropriate.

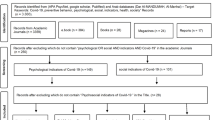

The Delphi process within this research comprised three rounds (Table 1). In round 1, 10 participants were presented with 10 open questions about the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial care, each of which had to be answered individually (Table 1). These questions were linguistically tailored to the specific target group in question while retaining the core message of the question posed.

Following this first round, the participants’ responses were independently and ethnographically analyzed (Altheide and Schneider, 2013) by four researchers and structured into summarizing statements by each of the researchers individually. The four researchers presented and discussed their findings in a group session to reach a number of collectively endorsed statements and improve the structure and readability of statements. As a result, 23 statements covering seven thematic subdomains and two lists (one about vulnerable groups and one about useful resources) were produced (Tables 2–4). Grouping items into themes has been shown to assist panel members in making judgments and identifying any omissions in a questionnaire’s overall reasoning (Jorm, 2015). To ensure the methodological consistency and validity of the defined research statements, the entire process was reviewed by two researchers who were not involved in the analysis process.

In Round 2, participants were given an individualized survey that included the 23 statements and the two lists created in Round 1. They were then asked to individually score these statements on a 7-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Individual responses were then grouped into group averages for each statement, with a score equal to or higher than 5 out of 7 (i.e., a minimum 70%) combined with an interquartile interval (IQR) of a maximum of two considered a group consensus. The IQR is a measure of dispersion around the median that includes the middle 50% of responses. An IQR of zero indicates complete agreement among all panel members, and the higher the IQR, the greater the data dispersion. The IQR range is usually determined by the number of response choices and respondents involved, with more response choices and experts resulting in larger IQRs (Ramos et al., 2016; Chamers and Armour, 2019). An IQR of no more than two combined with a high average group score indicates a robust agreement among the experts involved in the research.

In Round 3, each participant received the group’s total response results and was given the option to correct their scores or add supplementary information as desired. Because none of the respondents indicated a desire to change their position and a strong consensus was reached for all but three of the statements, the fourth round of clarification or modification was not required in this study.

Delphi panel recruitment

There are no clearly established recommendations or unequivocal definitions of the required number of experts for a Delphi study (Wilhelm, 2001; Chalmers and Armour, 2019). As a matter of fact, the number of experts involved in a Delphi study varies significantly between studies, ranging from 4 to 3000 participants (Thangaratinam and Redman, 2005). In general, Delphi studies with fewer than ten participants are uncommon, and most Delphi uses a panel size of 10–100 experts (Wilhelm, 2001). In relation to the concept of saturation in qualitative research, some authors argue that in Delphi studies with panel sizes greater than 25–30, no new ideas are generated, or no improvements in results are achieved. A smaller homogeneous group reaches consensus faster than a larger heterogeneous group (Chalmers and Armour, 2019). However, the final determinant of panel size is frequently determined by a number of pragmatic factors such as, but not limited to, the question to be answered, delivery method, access to experts and resources, the timeframe of the study, and expenses.

More than the number of experts involved in a Delphi, the quality of the experts involved is critical to the validity of the research findings. Therefore, a careful selection of panel members who are both knowledgeable and experienced is required (Okoli and Pawlowski, 2004; Hsu and Sandford, 2007). While most Delphi studies employ professionals as experts, other types of expertise are increasingly being recognized, resulting in the inclusion of consumer and caregiver advocates on Delphi panels (Jorm, 2015). This was also the case in this study, where we identified and used three groups of experts: psychosocial care professionals, patient representatives, and informal caregivers.

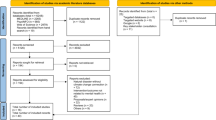

This particular Delphi study arose from the Belgian Superior Health Council’s working group "Covid-19 and psychosocial health". This is an officially recognized administrative body with a long history and well-established expertise in qualitative expert consultations. The Superior Health Council, thereby, has a large and active database of Belgian health experts - in this case, psychosocial health professionals, patient organizations, and informal caregivers—that can be consulted whenever a specific question arises. Using this network, an open invitation in the form of an expression of interest was sent to the entire database (N = 3.752), with a sample of 221 psychosocial experts initially expressing interest in participating in the Delphi. Following the receipt of additional information about the specific study, 195 experts effectively participated in round 1.

The non-probability purposive sample of 195 people included 149 psychosocial care professionals (85 French and 63 Flemish speakers) and 46 representatives of patient organizations and informal caregivers (14 French-speaking and 32 Flemish-speaking). The psychosocial care professionals came from a variety of backgrounds: 45 from a mental health care facility, 36 as an independent psychosocial care provider, 13 as directors of psychosocial networks, 25 as preventive psychosocial services providers, 11 academic researchers, and five who did not provide additional information about their background. Not all of the initial 195 provided their email addresses to be contacted again for the second round. Some representative organizations distributed the initial questionnaire to their members, who filled it out but did not leave their email addresses, preventing the researchers from contacting them again after round 1. This resulted in an initial core group of 148 participants, with whom the researchers could contact for round 2 following their participation in round 1.

Participants were required to respond across all Delphi rounds to complete the process. Therefore, those who did not respond to round 1 were not invited to round 2. As with all iterative study designs, there is a risk of dropouts or non-responders in this iterative study design. There is no set percentage of attrition that is acceptable in Delphi studies, but a dropout rate of 20–30% is said to be expected between rounds (Chalmers and Armour, 2019). As demonstrated by Table 1, 113 of those who were contacted also responded in round 2 (76%). Thus, the dropout was within the expected range. The dropout was also evenly distributed across the various categories of experts involved, resulting in no specific research bias in the results.

Results

A key first finding in this Delphi study is that there were no significant differences in the answers of the different types of experts involved, nor was there any linguistic difference, which could have been the case because, in Belgium, psychosocial care is influenced by both federal (Belgian) and regional (Flemish and French) competencies. Professionals, patients, and informal caregivers in both regions of the country seemed to be on the same page, and overall group consensus was robust for all but three statements, which will be discussed later.

The most substantial agreement (>5.90/7) was found for three statements, which are, in fact, indicative of three more general underlying tension fields identified during the Delphi research. Firstly, the experts indicate that the pandemic has increased social inequalities in society, raising the risk of long-term psychosocial problems (statement 18). The consequences of the pandemic, thereby, do not impact society as a whole equally, nor is the risk of long-term consequences equally distributed among all societal members. However, a second strong consensus demonstrates that there are aspects of the pandemic that impact psychosocial health in general for society as a whole (statement 10). According to the experts, the fear of getting contaminated or contaminating others, a psychosocial translation of the pathogen’s spread, creates additional pressure. It is a type of generalized constant mental strain that all people are experiencing during this pandemic, and it is wearing people down. Finally, the experts indicate a lack of strategic vision regarding psychosocial care as well as an underestimation of the importance of psychosocial health in society (statement 3). According to the experts, this lack of attention has several negative consequences for the population’s psychosocial health and the psychosocial care system.

Differences between societal groups

Experts believe that the impact of the pandemic on the general population is primarily due to the mental strain that the population is under and the constant need to adapt to changing circumstances (statement 11). Thus, the chronicity of the pandemic, as well as the flexibility required to cope with the duration of the measures implemented, causes this mental strain rather than the nature of the protective measures themselves (statement 15). According to the experts, general mental stress appears to be the most critical factor influencing the general population’s psychosocial health. Therefore, it is not surprising that statement 12, which linked the pandemic’s impact on the general population to the specific location of the workplace, received a disagreement score rather than an agreement score. The pandemic’s impact should be interpreted as more diffuse and covering all aspects of life rather than one specific subdomain.

According to the experts, the mental strain on the general population will have long-term consequences for their psychosocial health. Thus, they anticipate an increase in psychosocial problems among the general population as a direct result of the pandemic (statement 14). Experts agree with the literature that not paying enough attention to the psychosocial aspects of the pandemic will have a negative impact on the pandemic’s course and future development (statement 1). To back this up, experts agree that there is a need for a better understanding of the connection between existing data and analysis on the psychosocial impact of Covid-19 (statement 22).

The image of the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial aspects of society worsens when looking at more vulnerable groups in society. Experts believe that the elderly, people with lower socioeconomic status, pre-existing conditions, and family members of Covid-19 victims will be the most vulnerable groups during this pandemic. The pandemic has increased not only the number of psychosocial problems they face but also the severity of those problems, including psychopathologies (statement 17). While experts have previously stated a lack of attention to the psychosocial dimension of the pandemic, they emphasize that this lack of awareness is even more pronounced when discussing vulnerable groups, which are frequently underrepresented (statement 19). Finally, experts claim that social cohesion and solidarity within society have weakened due to the pandemic (statement 16).

Impact on psychosocial care

Aside from the impact on the people dealing with the pandemic, experts believe that the pandemic directly impacts the system level, i.e., psychosocial care. According to the experts, the preventive measures taken considering the biomedical discourse and pathogen containment have had a negative impact on the therapeutic relationship between professionals, patients, and caretakers (statement 6). Wearing a mask, maintaining a safe distance, and teleworking, according to experts, hampered both the operational level and the quality of the psychosocial care provided. Even more seriously, the continuity of care was jeopardized (statement 5). Several psychosocial services were forced to reduce or even close their operations during the pandemic. According to the experts, this has had a direct negative impact on the psychosocial health of already vulnerable people.

According to the experts, the psychosocial care system did not receive adequate government support to assist it in dealing with resource shortages (statement 4). Experts address the lack of attention paid to psychosocial care during the pandemic once more, citing insufficient support in both practical resources (e.g. IT, HR, finance, etc.) and critical pandemic-related preventive supplies (e.g. face masks, alcohol, etc.). This finding explains why two statements about IT and innovation during the pandemic did not achieve the level of robust consensus defined for this study. Statements 7 and 12 received a lower agreement score rather than a lower IQR score, indicating that the experts disagreed with the statement. Both statements questioned whether sector innovations (for example, teleconsulting) facilitated access to psychosocial care during the pandemic. Given that experts agree that significant problems arose in different aspects of psychosocial care due to these innovations, ranging from supply issues to a negative impact on the quality of care itself, this result confirms the sector’s struggles.

To contextualize the pandemic’s impact, experts state unequivocally that these problems did not arise out of nowhere and are, in fact, exacerbated mainly by the pandemic rather than caused by it. According to the experts, the psychosocial care system was under strain long before Covid-19 struck. In a sense, the experts argue that the sector was ill-prepared to deal with the challenges posed by the pandemic due to structurally embedded insufficient attention and support (statement 2). Experts, thereby, believe that the sector should ideally develop a coupling and dispatching system that can quickly capture psychosocial needs, triage, and refer as needed. Such a stepped or matched care system will ensure continuity of care and make it easier to respond quickly to (possibly changing) mental health needs (statement 21).

Unmet needs

The experts identified specific unmet needs that they encountered during the pandemic. According to the experts, the preventive measures at play during the pandemic impede the basic but necessary opportunities to recharge batteries, which act as a buffer for psychosocial health (statement 9). When combined with the constant mental strain of being contaminated and/or contaminating others (statement 10), this leads to energy depletion in the population. According to the experts, energy depletion is, therefore, a direct negative effect of biomedical discourse and preventive measures.

To complicate matters further, experts indicate that clear communication and guidelines are lacking (statement 8). According to the experts, there is a clear need for a better communication approach during this pandemic, as the current approach, or lack thereof, has a direct negative effect on the psychosocial health of the population.

Helpful resources

Experts also suggested a number of useful resources that should be further developed to prevent or at least minimize the psychosocial effects of the pandemic to better deal with the psychosocial impact of Covid-19. Among the various experts, the need for clear and trustworthy information, financial security, a healthy lifestyle, and a clear vision creating a sense of purpose stood out (Table 3). A lack of clear communication and guidelines was also identified as an unmet need and a critical factor negatively impacting psychosocial health (statement 8).

Lastly, experts emphasize the significance of social contact. Physical, social connections, whether with loved ones, psychosocial services, peers, or others, are preferable to digital contacts in terms of psychosocial health; however, the ability to have and maintain social connections seems to be the crucial finding. It is clear that we are all in this together and are looking for answers as a group. Within the work context, there should be sufficient flexibility and openness in management to deal with the challenges posed by the pandemic. Experts agree that campaigns and prevention messages can be beneficial; however, collective social initiatives did not meet the level of consensus robustness for this study (Table 5).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop a shared understanding of the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial care in Belgium. This Delphi study was able to reach a consensus amongst experts on all but three of the statements included in the study. The research findings, which are a representation of the lived experience of the experts involved in this Delphi, demonstrate that the experts, in general, believe that, first, there is insufficient attention paid to the psychosocial impact of Covid-19. Second, the current dominant biomedical discourse and preventive measures have some adverse effects on the psychosocial care system, directly impacting its remediation potential for existing and newly developing psychosocial problems within society.

Covid-19 appears to have stimulated innovation and, in particular, supplementary investments in the biomedical health setting in order to deal with the challenge at hand. Experts in this study claim that, while the impact of Covid-19 on psychosocial care was equally challenging, the sector did not receive the same level of necessary attention. Furthermore, the sector was ill-prepared due to a structural lack of attention and support long before Covid-19 struck. Innovations were thus simply impossible to realize, despite the sector’s efforts to implement, for example, blended care principles to deal with the preventive measures at hand. According to the experts, the innovations appear to be impeding the quality of the therapeutic relationship. However, it should be noted that telehealth—i.e., the use of information and communication technologies to promote health from a safe distance—is still relatively low in EOCD countries (Hashiguchi, 2020). As a result, knowledge about the development, implementation, and application of these innovations is still evolving, possibly even more so within the psychosocial sector. Therefore, more research is required to determine whether telehealth innovations can improve access to care during a pandemic and even in general when adequate support is provided to the sector. Therefore, one must also consider the people who use the services. Several researchers have indicated that, while telehealth innovations can be helpful during a contagious outbreak such as Covid-19, not everyone is equally capable of accessing and using telehealth innovations (Salari et al., 2020; Talevi et al., 2020). Telehealth, thereby, may not be the solution for all, and a blended care system or even physical proximity may be required for some to ensure the necessary quality of care, especially for the most vulnerable groups.

According to experts, the most severe negative effect of this pandemic’s unilateral implementation of the biomedical discourse has been the closure of several psychosocial care services. The closures were caused by preventive measures and policy decisions that did not consider the necessity of the continuity of psychosocial care. According to the experts, this is, first and foremost, a direct result of the sector’s structural lack of recognition in general, which has created several practical barriers impeding the sector’s ability to deal with the challenges of the pandemic (for example, lack of investment, lack of resources, etc.). The pandemic thus sustained and, to some extent, exacerbated the lack of attention, but it did not cause it. Second, the experts emphasize the importance of gathering more information and data on the effects of Covid-19 on psychosocial health. This implies, to some extent, that the experts believe that by demonstrating the impact of the pandemic on psychosocial health, the dominant biomedical discourse can be shifted toward a biopsychosocial model. This belief is consistent with international literature, which emphasizes the importance of a biopsychosocial approach in pandemic management (Cullen et al., 2020; Stuart et al., 2020; Wainwright and Low, 2020). As Shah (2021) discussed, various psychosocial data collection initiatives have been launched around the globe, and governments are gradually catching on. Although the future may bring change, experts believe that the closures have had a negative impact on the psychosocial health of the population, particularly the most vulnerable groups within society. One of the reasons for this could be that vulnerable groups are not always equally represented in science (for example, in surveys and clinical trials) and in public discourse. Because experts have indicated a need for more information about the psychosocial impact of Covid-19, special attention should be paid to the notion of representation of vulnerable and underrepresented groups. More research on the effects of underrepresentation and/or misrepresentation of vulnerable groups is required. While research on the pandemic focuses on the negative impact of the infodemic—i.e., an overload of information, including false or misleading information in digital and physical environments—and the need for proper communication in relation to the impact on psychosocial health (e.g. stereotypes, racism, anxiety, etc.), it rarely discusses the impact of under- and/or overrepresentation of certain groups in public discourse and the practical implications of this fact on the policy decisions which are taken (Talevi et al., 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Dubey et al., 2020; Mukhtar, 2020; Hossain et al., 2020). Researchers and policymakers should be susceptible to the issue of (mis)representation, especially in a digital age with social media and active lobby groups, because it is not always those who scream the loudest or are technologically savvy enough to get their voices heard are in most dire need. Certain vulnerable groups addressed by the experts in this study are, in fact, rarely mentioned in Belgian public discourse (for example, psychiatric patients, incarcerated people, etc.).

According to the experts, the pandemic is also clearly having a challenging impact on the psychosocial health of people in general. The constant mental strain of the pandemic and the preventive measures taken, combined with the lack of opportunities to recharge the batteries in this pandemic context, is described as a direct perverse effect of the pandemic on psychosocial health. This is problematic on at least two levels. Firstly, the longer the energy depletion endures, the higher the risk of psychosocial problems and even disorders developing in the general population. According to research, one of the first symptoms is already visible in society, i.e., sleep problems, which are linked to reduced immunity and a negative impact on both wellbeing and functional capacities (Vindegaard and Benros, 2020; Rajkumar, 2020; Pappa et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Lakhan et al., 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2020). Second, research has shown a link between fatigue, lack of motivation, and adherence to preventive measures, which directly impacts the biomedical course of the pandemic (IASC, 2020; Qiu et al., 2020; WHO, 2020). To adequately deal with the current public health challenge, it is therefore of societal importance to invest in preventive psychosocial measures that maintain the resilience level of the general population. According to the experts in this study, these preventative measures should focus on facilitating people to live a healthy lifestyle, which includes a certain level of social life, financial security, and a vision for the future. This will be a societal challenge for years to come, especially given the likely economic ramifications of the pandemic (Fong and Larocci, 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Chevance et al., 2020).

A more general conclusion of this Delphi research is that the pandemic does not impact society in the same manner or with the same intensity. The experts, thereby, warn that the psychosocial inequalities within society are on the rise. When combined with the notion that experts believe social cohesion and solidarity have decreased during the pandemic, one could argue that the pandemic is also impacting the psychosocial structure of our society, which will have long-term consequences. This is true not only at the county level but also at the global level. In a press release issued by the UN Security Council on January 25, 2021, senior officials warned that as the pandemic’s impact grows, the risk of tensions and instability will exacerbate inequalities in the global recovery effort (UN SC, 2021).

While the biomedical discourse has its merits, experts agree that a complementary psychosocial discourse exists that deserves equal attention for society to overcome the current public health threat and its larger consequences that are yet to come. According to the experts, it is highly recommended to strategically incorporate the prevention, detection, and treatment of psychosocial problems as a fundamental component of pandemic response planning. In terms of its impact on the course of the pandemic (e.g., compliance motivation regarding protective measures) and on the population’s current and future psychosocial health, psychosocial preparedness should be considered just as important as biomedical preparedness. Experts do not believe that the wheel should be reinvented to achieve this. Above all, they advocate for a strategic vision on psychosocial care and a focus on a stepped or matched care approach—ranging from prevention to specialized care–with targeted interventions to ensure that people get the help they need when they need it.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Supplementary information is readily available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Altheide D, Schneider C (2013) Ethnographic content analysis. Qual Media Anal 23–33. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452270043

Brewin C, DePierro J, Pirard P et al. (2020) Why we need to integrate mental health into pandemic planning. Perspect Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757913920957365

Bojdani E, Rajagopalan A, Chen A et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: impact on psychiatric care in the United States, a Review. Psychiatry Res 289:113069

Chalmers J, Armour M (2019) The Delphi technique. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer, Singapore

Cullen W, Gulati G, Kelly BD (2020) Mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic. QJM 113(5):311–312. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa110

Campion J (2020) Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 8:657–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30240-6

Chevance A, Gourion D, Hoertel N et al. (2020) Ensuring mental health care during the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in France: a narrative review. L’Encephale 46(3):193–201

Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KE et al. (2020) Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 69:1250–1257. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4externalicon

De Meyrick J (2003) The Delphi method and health research. Health Educ 103:7–16

Diamond IR, Grant RC, Feldman BM et al. (2014) Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. J Clin Epidemiol 67:401–409

Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R et al. (2020) Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr: Clin Res Rev 14(5):779–788

Fong V, Larocci G (2020) Child and family outcomes following pandemics: a systematic review and recommendations on COVID-19 policies. J Pediatr Psychol 45(10):1124–1143

Gray R, Sanders C (2020) A reflection on the impact of COVID-19 on primary care in the United Kingdom. J Interprof Care 34(5):672–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2020.1823948

Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R et al. (2020) Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res 291:113264

Hashiguchi T (2020) Bringing health care to the patient: an overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 116. OECD Publishing, Paris

Hossain MM, Tasnim S, Sultana A et al. (2020) Epidemiology of mental health problems in COVID-19: a review. F1000Res 9:636

Hsu CC, Sandford BA (2007) The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Asses Res Eval 12. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n10.pdf

IASC–Inter Agency Standing Committee (2020) Note d’information: prise en compte des aspects psychosociaux et de santé mentale de l’épidémie de Covid-19. https://interagencystandingcommittee.org/iasc-reference-group-mental-health-and-psychosocial-support-emergency-settings/interim-briefing-note-addressing-mental-health-and-psychosocial-aspects-covid-19-outbreak

Jorm AF (2015) Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 49(10):887–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415600891

Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V (2020) Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 293:11338

Lakhan R, Agrawal A, Sharma M (2020) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress during COVID-19 pandemic. J Neurosci Rural Pract 11(4):519–525

Linstone HA, Turoff M (eds) (2002) The Delphi method: techniques and applications. pp. 3–12

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M, Wang H (2020) The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on Medical Staff and General Public—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 291:113190

Mukhtar S (2020) Psychological health during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic outbreak. Int J Soc Psychiatry 66(5):512–516

OECD (2020) Beyond containment: health systems responses to COVID-19 in the OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=119_119689-ud5comtf84&title=Beyond_Containment:Health_systems_responses_to_COVID-19_in_the_OECD

Okoli C, Pawlowski SD (2004) The Delphi method as a research tool: an example, design considerations and applications. Inf Manag 42:15–29

Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T et al. (2020) Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun 88:901–907

Qiu J, Shen B, Wang Z et al. (2020) A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatr 33:100213

Rajkumar RP (2020) COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr 52:102066

Ramos DGG, Arezes PM, Afonso P (2016) Application of the Delphi Method for the inclusion of externalities in occupational safety and health analysis. DYNA 83(196):14–20. https://doi.org/10.15446/dyna.v83n196.56603

Rawaf S, Allen L, Stigler F et al. (2020) Lessons on the COVID-19 pandemic, for and by primary care professionals worldwide. Eur J Gen Pract 26(1):129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/13814788.2020.1820479

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R et al. (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob Health 16:57

Shah H (2021) COVID-19 recovery: science isn’t enough to save us. Policymakers need insight from humanities and social sciences to tackle the pandemic. Nature 591(503). https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-021-00731-7

Silva E, Ono BHVS, Souza JC (2020) Sleep and immunity in times of COVID-19. Rev Assoc Med Bras 66(2):143–147

Steinert MA (2009) Dissensus based online Delphi approach: an explorative research tool. Technol Forecast Soc Change 76:291e300

Stuart K, Faghy MA, Bidmead E et al. (2020) A biopsychosocial framework for recovery from COVID-19. Int J Sociol Soc Policy 40(9):1021–1039. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-07-2020-0301

Talevi D, Socci V, Carai M et al. (2020) Mental health outcomes of the CoViD-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr 55(3):137–144

Thangaratinam S, Redman CW (2005) The Delphi technique. Obstet Gynaecol 7(2):120–125

UN SC (2021) Risk of Instability, Tension Growing, amid Glaring Inequalities in Global COVID-19 Recovery, Top United Nations Officials Warn Security Council. https://www.un.org/press/en/2021/sc14422.doc.htm

Verhoeven V, Tsakitzidis G, Philips H et al. (2020) Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the core functions of primary care: will the cure be worse than the disease? A qualitative interview study in Flemish GPs. BMJ Open 10:e039674. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039674

Vindegaard N, Benros ME (2020) COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav Immun 89:531–542

Wainwright TW, Low M (2020) Why the biopsychosocial model needs to be the underpinning philosophy in rehabilitation pathways for patients recovering from COVID-19. Integr Healthc J 2(1):e000043. https://doi.org/10.1136/ihj-2020-000043

Walsh F (2007) Traumatic loss and major disasters: strengthening family and community resilience. Fam Process 46:207–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2007.00205.x

WHO—World Health Organization. Mental health and psychosocial considerations during COVID-19 outbreak 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

Wilhelm WJ (2001) Alchemy of the Oracle: the Delphi technique. Delta Pi Epsil J 43:6–26

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Superior Health Council of Belgium, the members of the expert group on Covid-19 and psychosocial health, and all the experts involved in the Delphi research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required. Within a national expert group, experts from the field freely and willingly provided information on their experience during covid-19 in light of writing policy recommendations and publications.

Informed consent

Within a national expert group, experts from the field freely and willingly provided information on their experience during covid-19 in light of writing policy recommendations and publications.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van den Cruyce, N., Van Hoof, E., Godderis, L. et al. The impact of Covid-19 on Belgian mental health care: A Delphi study among psychosocial health professionals, patients, and informal caretakers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 330 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-01008-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-01008-0