Abstract

Complex societal and environmental challenges motivate scholars to assume new roles that transcend the boundaries of traditional academic expertise. The present article focuses on the specialised knowledge, skills, and practices mobilised in the context of science–policy interfaces by researchers who advise policymakers on collaborative governance processes intended to address these pressing issues. By working on the backstage of collaborative arrangements, researchers support policymakers in the co-design of tailor-made strategies for involving groups of institutional and non-institutional actors in collaboration on a specific issue. The present article examines the expertise underpinning this practice, which we term process expertise. While already quite widely practiced, process expertise has not yet been comprehensively theorised. The study employs a self-reflective case narrative to illuminate its constitutive elements and investigates the advisory work of the authors’ research team, called “Co-Creation and Contemporary Policy Advice”, located at the intersection of science, policymaking, and civil society. The findings show that process expertise, when exercised by researchers and supported by an assemblage of enabling conditions inherent to the research context, goes beyond the possession of a set of skills at the individual level. Instead, process expertise in the context of science–policy interfaces unfolds in interaction with other types of knowledge and fulfils its task by generating a weakly institutionalised “in-between space”, in which researchers and policymakers interact to find more inclusive ways of tackling complex challenges. In this realm, relational work contributes to establishing a collaborative modus operandi at the very outset of the advisory process, while working at the processual level supports knowledge co-production among multiple actors. The article argues that it is the ongoing work of process experts at the intersection of relational and processual levels that helps maintain momentum in these collaborative partnerships. By formulating and discussing five constitutive elements of process expertise, this paper untangles the complex work that is required in collaborative research settings and gives a language to the invisible work performed by researchers who offer policymakers—and other invited actors—advice on the process of designing collaboration in collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over recent decades, the rise of complex societal and environmental challenges, ranging from climate change to the current COVID-19 pandemic, has increasingly fostered a debate on the potential roles that researchers can or should play in addressing these pressing issues (Pohl et al., 2010). The present article focuses on the specialised knowledge, skills, and practices of researchers who advise policymakers on collaborative governance. In this context, one or more institutional authorities opens up previously closed policy arenas to a larger group of (institutional and non-institutional) actors. The expectation is to generate a broader and multi-perspective understanding of the issue at hand, foster creativity in the generation of solutions, and enlarge societal support for their implementation (Torfing and Ansell, 2017, p. 37). Accordingly, the advisory paradigm of “speaking truth to power”, that is of offering evidence to support decision makers, has opened up for “making sense together” (Hoppe, 1999, cf. also Hoppe, 2005, 2009; Pielke, 2007; Renn, 1995; Strassheim and Canzler, 2019), thus broadening expectations towards researchers’ expertise in policy advice and calling for the rearticulation of the interactions between experts, policymakers, and citizens (Carrozza, 2015; cf. Fischer, 2000). With an underlying understanding of the policymaking process as “collective puzzlement” (Heclo, 1974, p. 305, cited in Hoppe, 2011), knowledge production, intended as “a group activity” (Bandola-Gill and Lyall, 2017, p. 254), has shifted from the linear “knowledge transfer” towards the interactive “knowledge exchange” (Mitton et al., 2007).

Many attempts have been made to typologise the use of advice in the policy process (Aubin and Brans, 2021), including advisers’ roles (Connaughton, 2010; Mayer et al., 2004; Pielke, 2007), as well as the style and the substance of advice offered (Howlett and Lindquist, 2004; Prasser, 2006). Providing advice on collaboration involves offering substantive input on how to design respective processes (SAPEA, 2019, p. 58; see also Brand and Karvonen, 2007; Fischer, 2009; Maasen and Weingart, 2005; Martinsen, 2006). But it also requires the ability to foster a “creative attitude” (Follett, 1930, p. 211) in the advisory arena that is necessary to collectively address complex issues. As no domain-specific excellence translates automatically into this competence (Bammer et al., 2020; Bennett and Brunner, 2020; Escobar et al., 2014; Fischer, 2012), further research is needed with respect to the constitutive elements of such an expertise, which we term process expertise. The present article takes up this challenge.

This exploratory work builds upon advisory activities at the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies (IASS) in Potsdam, Germany, where our research group (“Co-Creation and Contemporary Policy Advice”) has experimented with and conducted research on collaborative approaches at the intersection of science, policymaking, and civil society. These include, for instance, supporting local municipalities in co-developing (along with societal actors) mobility strategies in public space during the COVID-19 pandemic; planning together with city mayors and public servants the implementation of citizen councils to set priorities for the future development of a district in Berlin; and advising regional and national governments on how to co-develop pathways towards a sustainable future together with affected actors, as part of the coal phase-out in the Lusatia region.

To conceptualise the kinds of expertise underpinning this practice, and thus contribute to the related debates, we scrutinise our experiences and undertake a self-reflective case narrative (Becker and Renger, 2017), inquiring: “What do researchers do (and how) when they advise policymakers on collaboration processes, and what kind of expertise do they rely on?” To approach this question, we offer an overview of the main debates on how to define expertise, provide an exploratory definition of process expertise in the context of science–policy interfaces, and substantiate this with literature dealing with facilitation; secondly, we introduce the context of our advisory work at the IASS and illustrate the research methods underpinning our investigation; thirdly, based on the results of our analysis, we formulate and discuss five constitutive elements of process expertise. Finally, we reflect on the pathways for improving the application of process expertise that is necessary in such advisory contexts within and beyond academia.

Defining expertise

Anyone trying to offer an answer to “what expertise really is and how it actually works” (De Donà, 2021, p. 82) enters surprisingly slippery semantic ground. On the one hand, everyone seems to understand the term ‘expertise’ in its everyday use. The more or less common ground is rooted in the etymology of the word expert, from the Latin verb experiri, namely “to try”. A related expertus is “someone who is experienced, has risked and endured something, is proven and tested” (Grundmann, 2017, p. 27). On the other hand, the tendency observable in scholarly disputes is rather to underline the challenge of offering a straightforward or uncontested definition of this concept (cf. Ward et al., 2019) without ending in the tautological trap of defining expertise as “what experts have that non-experts do not” (Nunn, 2008, p. 415).

Different disciplines and approaches to the study of expertise offer alternative perspectives on this subject (Ward et al., 2019). One of the biggest debates unfolds between those scholars who hold that expertise is relational (Grundmann, 2017), namely “constructed” in dialogue with certain audiences (Pfister and Horvath, 2014), and therefore attributed by someone else (Kotzee and Smit, 2018, p. 99; see also, e.g., Fischer, 2009; Jasanoff, 2003; Wynne, 2003), and those who see expertise as “real, namely relying on the experience and competencies of the person” (Kotzee and Smit, 2018, p. 100, referring to Longino, 2002). Another strand of debate differentiates between expertise as an “internal property” of a person, resulting from constant individual practice, or as an “external construct of a community”, thus also including its consumers and regulators, and the context in which expertise operates (Nunn, 2008, p. 414). A practice perspective suggests moving away from understanding expertise as “owned” towards being “applied”, which combines “understanding and doing” (Pellizzoni, 2011, p. 766, p. 767, also referring to Turner, 2003; Goldman, 2006; Schatzki, 2001). Eyal and Pok move even further away from the actor-centred perspective and perceive expertise as “in-between space” connecting different arenas (2015, pp. 41–42). In these terms, expertise includes devices, tools, the contributions of other experts, institutional and spatial arrangements, and the concepts that organise experts’ intervention (Eyal and Pok, 2015, p. 47). Eyal (2019) also adds another major line of debate, namely whether expertise is a matter of embodied and tacit knowledge, or rather of abstract and explicit rules.

Collins et al. (2016, p. 109), who advocate for realistic accounts and for retaining “a separate sphere for technical debates so as to preserve a notion of expertise”, notably differentiate between “interactional” expertise, which allows for conversing with experts within a field, and can be gained by immersion within a specific discourse of a given domain, and “contributory” expertise, which allows not only for conversing, but for making contributions to a field in question. One becomes a contributory expert by collaborating with other contributory experts and acquiring their skills, being immersed not only via language, but also via practice (Collins, 2014, p. 65, cited in Grundmann, 2017, p. 33). The concept of interactional expertise has initiated much interest in the forms, skills, and motivations behind collaboration among experts from different disciplines. Contributing to this strand of research, Kennedy (2019) distinguishes four different categories of motivation for developing interactional expertise. The respective profiles include “learners” (who want to gain knowledge about a target field), “challengers” (who want to influence or change a given domain), “collaborators” (who are interested in learning and working across sectors), and “mediators/facilitators” (who are driven by an interest in “resolving a disagreement or enabling dialogue, the experience of learning about each group, or the process of assisting in the bridging of these divides”) (p. 225, p. 226). Acquiring the vocabulary of another scientific community might also play a key role in a trading zone, in which some kind of “pidgin” or “creole” (Galison, 2010, p. 25) is created for the purpose of communication across disciplines. This trading zone, facilitated by interactional expertise, has the potential to become a new field of expertise (Gorman, 2010). Barley et al. argue that the management of information and communication within and between domains “involves its own, unique forms of knowledge”, which they call process expertise (2020, p. 5, p. 6).

Throughout the literature on expertise, several authors claim to offer a pragmatic conceptualisation of expertise that could allow productive exchange among research communities and offer some guidance despite ongoing disputes and divides (cf. SAPEA, 2019). One possibility is to acknowledge the context-related usefulness of different traditions of expertise studies, as “[n]o single notion related to expertise is necessary or sufficient for or definitive of expertise” (Nunn, 2008, p. 415). Another possibility is to look for a common denominator, as in the case of Kotzee and Smit (2018, p. 113), who aim to overcome the divide between constructivist and realist approaches through “a single, coherent conception of expertise”, which they explain as “a three-part relationship among a subject, an object and a comparison class”. Garret et al. (2009) criticise the discipline-bounded nature of studies on expertise and argue against the use of categories such as “explicit” and “tacit” that—in their view—offer “little underlying information as to the make-up of the expertise” (p. 93) and are mutually exclusive (p. 94). They instead propose viewing expertise from a multi-disciplinary perspective and provide a comprehensive account that focuses on three interrelated factors: “the content of knowledge required to complete a task at the individual or group level, the operational context for which that knowledge is useful, the process by which that knowledge is utilised” (2009, p. 100, p. 103, emphasis added). In the next section, we propose an exploratory definition of process expertise based on these three coordinates.

Process expertise

The term “process expertise”—with various linguistic nuances—has already been proposed by several authors to illustrate expertise focused on the process of engagement (Escobar, 2015), on communication within and across domains (Barley et al., 2020; Treem and Barley, 2016), on the art of creating “forums that give voice to publics” (Felt and Fochler, 2010, p. 220), and on interacting with local knowledge (Yanow, 2003). Chilvers speaks of “participatory process experts” by referring to those “who design, facilitate, and evaluate participatory processes and articulate public understandings” (2008, p. 162). Moore contrasts “substantive expertise” on the matter of deliberation with “processual expertise”, defined as “the expertise of facilitators in conducting deliberations” (2012, p. 153). While many of these definitions hint in the same direction as our understanding of process expertise, as yet there is no systematic elaboration on the constitutive elements of the concept. Lee, in her long-term study of public engagement professionals, states that “there is no name for what dialogue and deliberation experts do” (Lee, 2015, p. 55). In this article, we take on the challenge of rendering process expertise more identifiable, systematised, and accessible (Bammer et al., 2020, p. 8), and focus on expertise mobilised by researchers while advising policymakers on collaborative arrangements.

As a first step, we present our exploratory definition of process expertise in the context of science–policy interfaces, by following the three elements suggested by Garrett and colleagues’ (2009) framework (content; operational context; process):

Process expertise consists of knowledge on process design (content) for planning collaborative arrangements with policymakers in advisory settings (operational context) by facilitating knowledge co-production among involved actors (process). Process expertise, in other words, offers advice on the process for designing collaboration in collaboration.

In the next two subsections, we substantiate this definition by building upon literature devoted to facilitation. An exhaustive review of all debates on the topic would exceed the scope of this article; consequently, the goal is to identify key elements to provide a foundation for our empirical analysis.

The makers of collaboration

The “makers” (Lee, 2015) of collaborative settings are variously referred to in the literature as experts of community (Rose, 1999), public engagement professionals (Lee, 2015), facilitative leaders (Gash, 2016), professional participation practitioners (Cooper and Smith, 2012), or deliberative consultants (Hendriks and Carson, 2008). We call them facilitators (Dillard, 2013; Escobar, 2019; Mansbridge et al., 2006; Moore, 2012). Literature dealing with facilitation offers key insights into both the content of knowledge and the process by which process expertise is utilised to establish and nourish collaborative environments, conceived as an “extremely sophisticated” (Lee, 2015, p. 224), “invisible”, but “persistent and skilled labour” that operates at a relational, pragmatic and political level (Bennett and Brunner, 2020, p. 10, p. 15).

A wide variety of practices lies at the foundation of facilitation work (Bryson et al., 2013; Jacobs et al., 2009; Mansbridge et al., 2006). One strand of the literature focuses on the skills that support collaborative work. Quick and Sandfort, who investigated the learning practices of facilitators, summarise them as “skills for managing discursive exchange and group dynamics” (2017, p. 235). Another strand aims at uncovering the rationale which guides facilitators’ action. Escobar frames the work of facilitators in Goffmanian terms of “seeking to assemble new interaction orders by carrying out transformative processes” (Escobar, 2014, p. 256). Goffman (1983, p. 5) defines interaction orders as “domain[s] of activity” that lay “the ground rules for a game” such as a country’s traffic code or a language’s grammar. By focusing on the quality of interaction with counterparts, facilitators foster new modes of relating to each other (Escobar et al., 2014, p. 92), build and maintain relationships (Escobar et al., 2014, p. 460; Bennett and Brunner, 2020; Westling et al., 2014), and support the group in developing readiness to “visualise reality from the perspective of others” (Williams, 2002, p. 115). A third strand focuses on facilitators’ activities and approaches to shape the communicative process with norms and rules towards “rigorous deliberative exchanges” (Dillard, 2013, p. 218). Deliberative practitioners “listen critically to appreciate multiple forms of knowledge” (Forester, 2013, p. 19) and activate the tacit knowledge of the group (Quick and Sandfort, 2017). Facilitators do not perceive themselves as substantially contributing to the discussion (Escobar et al., 2014, p. 96), so that their interventions are considered successful if participants perceive their role as “invisible” (Lee, 2015, p. 114). In this regard, Fischer speaks of “participatory expertise” as a new kind of expertise, where “the participatory professional operates from the local contexts in its own terms, rather than prescribing premises from above” (Fischer, 2003, p. 190).

The backstage of collaboration

The operational context on which much attention in the literature is focused refers to the so-called “frontstage” of collaborative arrangements, namely the performative phase in which the involved actors come together to deliberate (Escobar, 2015). While these studies offer important insights into the mechanisms of collaborative governance (e.g. communicative methods, participants’ recruitment strategies, choice of themes, role of facilitators), they only investigate one side of the coin. Such a perspective, indeed, “lack[s] accounts of the backstage policy work carried out […] to set up the frontstages of participatory governance” (Escobar, 2015, p. 3, italics in original, building on Goffman, 1971). It is on the backstage that the making of collaborative governance actually takes place and where fine-grained choices shape the rationale, framing, and rules structuring the collaborative space (Molinengo, forthcoming). Here, those responsible for a collaborative arrangement “[turn] myriad agendas, actors, interactions, spaces, materials… into manageable plans and stories” (Escobar, 2019, p. 188) and develop a process design, which functions as a roadmap for collaboration (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Bryson et al., 2013; Kadlec and Friedman, 2007). Process design “describes the where, when, and how of collaborative governance” (Purdy, 2012, p. 411) and includes decisions on—among others—the participants to be invited, modes of interaction and communication to be implemented, information to be shared, and results to be produced (Bobbio, 2019, p. 43). For a collaborative process to be productive, therefore, involves much more than “the pragmatic work of facilitating a discussion” (Forester, 2013, p. 18).

Research methods

The investigation is based on a self-reflective case narrative that “prioritize[s] the narrator’s own meaning making” (Becker and Renger, 2017, p. 141), focused on the work of our IASS research team in ongoing advisory processes. The institutional context of IASS, within which the project operates, is unique: The institute was founded in 2009 as a joint initiative of the German Federal Government, the Federal State of Brandenburg, and the research organisations of the German Science Alliance, with a mandate to understand, advance, and accompany transformations towards sustainable development. To pursue this, IASS has developed a specific research approach (Nanz et al., 2017), based on the interplay between transformation and transformative research. While transformation research “studies the conditions, mechanisms and causes of processes of social change [and] generates descriptive or analytical knowledge”, transformative research “aims to advance and facilitate processes of societal change by developing possible solutions and supporting their implementation through inter- and transdisciplinary research practice” (Meisch, 2020, p. 8). Providing policy advice, therefore, is closely connected to the IASS’s founding mandate and to part of its research approach. Five-year periods of basic funding, access to communicative channels with the policymaking field at national, regional, and local levels, and to relevant networks provide fertile ground for researchers to experiment with forms of policy advice that aspire to be, as our German project title says, “zeitgemäß”, namely aligned with the complexity that shapes current sustainability issues. Within this context, we zoomed in (Nicolini, 2009) on different exemplars (Flyvbjerg, 2006) of our practice in the years 2017–2020.

The case study

The case study examines our team members’ practices when co-designing with policymakers—and other invited actors—tailor-made strategies to include a broader circle of actors in addressing complex societal and environmental challenges. Their advice does not offer the policymaking counterpart potential solutions for the issue to tackle; instead, it designs the communicative path to address the problem at hand collectively. To exemplify, we briefly introduce two ongoing activities led by IASS team members:

The first activity involves advising a local Berlin municipality on collaborative mobility transition strategies in the city. Since 2019, at the heart of this advisory activity is the establishment of regular meetings among public servants, politicians, researchers, and civil society organisations, co-initiated and facilitated by a member of our research team, wherein different logics can confront and learn from each other. At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, when public administrations faced strong pressure to act and many people started shifting their work activities online (many for the first time), this pre-established communicative routine enabled collaborative, focused and productive online meetings. In this setting, researchers facilitated a knowledge co-production process of prototyping a series of unprecedented mobility measures to guarantee citizens safe bicycle trips across the city and social distancing in public spaces (e.g. bike lanes and temporary play streetsFootnote 1) and advised the group on how to include the citizenry in their planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Another activity consists of planning—together with a mayor and public servants of another Berlin district—a sequence of so-called citizen councils (Asenbaum, 2020; Rough, 2002), a participatory format made up of 12–15 randomly selected citizens, to formulate recommendations to the local administration concerning the future development of the district. The process began when a citizen initiative contacted a team member due to his expertise around this participatory method. He then supported the citizen group in drafting and presenting to the municipality a proposal to host citizen councils. Within just a few weeks, the citizen representatives and district mayor met to discuss the idea. The researcher has since worked with this multi-stakeholder group to design the collaborative activities, embed the citizen councils’ results within the political agenda, and is currently supporting the mayor and public servants in developing competencies to undertake a more responsive role in these participatory processes.

Data collection

This study has a basic, yet potentially problematic assumption: we assume that the concept of process expertise can be investigated by analysing the practices of our team. In doing so, we place ourselves in the role of process experts, at the risk of seeming arrogant to the reader and, most importantly, of lacking the necessary critical distance to the object of study. In order to address this issue, we undertook the following measures in our data-collection strategy: 1. We employed a reflection-in-action approach (Schön, 1987), in order to decrease the “chronological–physical separation from action, such that reflection can usefully be said to take place in the midst of action” (Yanow and Tsoukas, 2009, p. 1340); 2. To better identify potential gaps and shadows in our conceptualisation of process expertise, we invited an external researcher [RF] to contribute to this study as a third author; 3. To navigate our positionality in each step of the process of data collection and analysis, we followed the “formative accompanying research approach” (FAR) conceived by Freeth and Vilsmaier, which centres on the “dynamic positionality” of the investigators between learning about, with and for a collaborative research team (2020, p. 2). Drawing on selected elements of FAR, we divided the data-gathering strategy into two main phases:

The learning about phase included:

-

1.

Self-reflection by the first author [GM] on the motivation and scope of the present study (Becker and Renger, 2017), based on the author’s own assumptions about the practice of process expertise and participatory observation in advisory processes.

-

2.

Three reflection rounds on (point 1) together with the second author [DS] (project lead) and the third author [RF] (senior fellow and later associated scholar at the IASS).

-

3.

One-to-one semi-structured interviews with each of the six members of the team (including GM and DS), focused on specific exemplars of their advisory activities. To collect information, we undertook a practice-centred approach and investigated how interviewees construct the problems they intend to tackle and how solutions are achieved through processes of structured interaction (Colebatch, 2006, p. 314).

The subsequent learning with phase, which took place two weeks after the last interview had been conducted, consisted of a two-hour collective reflection with the team members on their practice, in order to expand reflexivity at a group level (Berger, 2015, p. 222). This balanced input elements (e.g., sharing results from the interviews) with other activities in order to enquire, even provocatively, about team members’ positionalities (e.g., “Are you a researcher, an advisor, or a process designer?”). The core element comprised two rounds of collective sense-making, wherein team members reflected on the key skills behind their practice and the challenges of fulfilling an advisory role. Within this setting, GM acted as first moderator for the discussion, with DS participating in the discussion and acting as second moderator in case GM wished to intervene as a participant. RF offered observations toward the end of the conversation and invited the group to elaborate on specific issues. In this way, we worked transparently in different roles and, at the same time, gained some critical distance thanks to the third author’s presence. Following the data analysis and an initial draft of the present article, team members were invited to critically comment on the draft text.

The final learning for phase is beyond the scope of the current article; rather, we expect the present article to become the foundation for future analysis. Subsequently, a future discussion round, involving the same constellation of participants, will critically approach the effects of these lessons on the team members’ practice, and identify actions to integrate this kind of expertise more strongly into the team’s work.

Data analysis

The data analysis combines an abductive approach (Blaikie and Priest, 2019; Schwartz-Shea and Yanow, 2012) and grounded theory (Bryant and Charmaz, 2007; Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Strauss and Corbin, 1990). We thereby integrated our experience in advisory settings with new data emerging from empirical work explicitly focused on our specific research question, and respective debates in the literature. In the first stage of analysis, we reviewed the data generated in the learning about phase through an iteration of open coding of the one-to-one interview transcripts. Building on this, we identified thematic categories that supported a second round of coding and integrated the analysis of the two-hour collective reflection transcripts. Also in this analysis phase, roles were split in order to foster critical reflection: GM analysed data, while DS and RF pointed “to possible projections and ignoring of content by the researcher” (Berger, 2015, p. 230) in the ways that the data had been interpreted.

Results

In this section, we present findings related to process expertise based on the analysis of the advisory practice of designing collaboration in collaboration with policymakers. We do so by illustrating: 1. the researchers’ guiding rationale in these settings; 2. the relational and processual levels at which process expertise operates; 3. the skills underlying process expertise; 4. a conceptualisation of process expertise as operating in an “in-between space”; 5. the conditions that enable researchers to operate as process experts in advisory settings.

The researchers’ guiding rationale

Depending on context, researchers might follow different motivations to engage in the processes of collaboration and to develop the skills required to collaborate effectively. Kennedy (2019) offers insights into developing interactional expertise in interdisciplinary cooperation, whereas we offer a more transdisciplinary perspective and concentrate on collaboration between experts and policymakers in the context of science–policy interfaces.

The rationale guiding team members’ activities in their advisory practice entails achieving both societal and research impacts. In terms of societal outcomes, researchers aim to establish new interaction orders (Escobar, 2014; Goffman, 1983) within the democratic system, at both macro and micro levels. The generation of new “interactions”Footnote 2, specifically in contexts where “societal change is currently being shaped, negotiated, or even contested”, emerged as a recurring theme in the analysis. Referring to the macro level, one researcher involved in implementing citizen councils at municipality level framed their rationale in terms of “upgrading” the current political system and the ways in which different groups of actors interact with each other. Following this, another researcher mentioned their work with Berlin policymakers on drafting and implementing a new mobility law. In their understanding, the co-design of a collaborative process to involve civil society in developing new measures for the city’s mobility transition attempted to generate “collective meaning” beyond the production of a simple “piece of paper”. It fostered citizens’ understanding and, consequently, their active participation in the implementation stage. Researchers observe that the problems plaguing communication in policymaking processes also manifest at the micro level. One researcher mentioned experiences from the annual Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP) in 2018, where: “you often have three or four people speaking on a podium, and then people sitting in rows of chairs, who are supposed to listen, but who are actually writing emails and playing on their mobile phones”. Researchers’ counterproposal to what they called a “format for downloading information” (or, as framed in a blog article by one of the team members, “a culture of untapped potential”, cf. Bruhn, 2017) was to substantiate the scope of the conference—namely networking, lobbying and decision making—with the establishment of a “Co-Creative Reflection and Dialogue Space” at the following COP in Madrid in 2019. Here, they initiated dialogue sessions at which participants were invited to generate new ideas on how to improve the culture of interaction at the COP (Wamsler et al., 2020).

From a research perspective, the guiding rationale consists of establishing new interaction orders between researchers and policymakers with the intention of generating knowledge from and for the practice. In these advisory settings, team members attempt to foster a mutual learning cycle with the actors they are working with: “we try to bring them together, by learning with them and, at the same time, to share with them what we have learned”. By participating actively in the backstage of policy processes, researchers have “access” to information, actors, and networks they would not normally have and the chance to closely investigate those (micro) dynamics that influence the design and implementation of such collaborative spaces: “At the same time, as a social scientist, while hearing the counterpart’s expectations, you are also listening-in to your research subject. […] you are thereby learning a lot—not only at a strategic level, but you also gain a better idea of what could actually be investigated.”

The interplay of relational and processual levels

Our analysis shows that process expertise operates at two levels: relational and processual. These two levels complement each other. The relational level helps create conditions conducive to collaboration, while the processual level takes advantage of those conditions to co-design a collaborative strategy within the advisory setting.

Relational level

Working at the relational level aims to facilitate the creation of collaborative relations in the setting where process expertise operates. Thus, our first argument is:

-

1.

Process expertise generates conditions at the relational level for the advisory process to take place.

At the macro scale, the task consists of creating new communication channels within or beyond a given organisation, and of generating institutional support, and thus legitimacy, for the emerging collaborative process to take place. This work entails creating the conditions for different actors to meet in a common setting, experience the mutual benefit of working together (Townsend, 2014, p. 117) and the resulting “collaborative advantage” (Huxham, 1996) of these spaces. One example here is citizen councils where, during the design phase, a team member suggested building a “project group” responsible for steering the process. This group featured the mayor, civil servants from the city district, representatives of political parties, and representatives of the citizen initiative. The researcher supported the group in drafting agendas in advance of their meetings and facilitated the sessions in the background by posing questions and ensuring all voices were being heard. Bringing together a constellation of such diverse actors and facilitating their interactions had two goals, according to the researcher. First, it established new relationships between policymakers and civil society to synergistically combine resources (e.g., knowledge, funding). Second, it fostered alliances among individuals, which also contributed to sustainable communication ties during the implementation phase. After one year, as the researcher reports, “we have built up a basis of trust, and the communication flow works fine. […] People have found each other”. Yet, relational work also takes place by spontaneous interventions ‘in situ’. For instance, a researcher involved in advisory activities on the coal phase-out process in the Lusatia region intentionally made use of a frontstage event featuring both political representatives and local actors in order to establish new relations between these two groups that otherwise had limited opportunities to communicate: “I went to [name of politician] in a break […] and […] figured that he needed two things. Then I said, okay, one of these issues can be discussed right now [during the workshop]”. In the following workshop session, the researcher raised the issue and invited local actors to contribute their experience. This intervention also had effects at the processual level: it resulted in the co-design of a local participation strategy presented to the regional government. In this way, the researcher made use of a frontstage event to inform policymakers, working backstage on upcoming collaborative arrangements, and fostered co-production between the two settings.

At the micro level, relational work focuses on face-to-face interactions (Escobar et al., 2014) and encourages reciprocal listening, reflection, and an atmosphere of trust. Building a rapport between counterparts, respectful of divergent positions, can open up resources and knowledge normally not shared in such processes. A researcher describes how the initially defensive attitude of the interlocutor (“their body language was something like: ‘we are ready for confrontation’”) changed when he suggested starting the meeting by discussing each person’s personal motivation for participating in the process: “At that point you could notice how their body language relaxed, and they said: ‘Okay, now we have to re-think this whole event. Good to know that you are interested in our opinion, and that you want to listen to our concerns’”. This example shows how process expertise explicitly contributes to generating new interaction orders by fostering communicative framings “beyond fixed interests and positions”. Researchers can also introduce new interaction orders by embodying them. For example, a team member related how he and colleagues initiated the “Co-Creative Reflection and Dialogue Space” at the COP in Madrid. Since this was an uncommon format for the audience of negotiators, climate policy advisors, and scientists, the researchers encountered some difficulties in recruiting participants. The three researchers therefore decided to sit in the middle of the room and started a dialogue with each other: “and just because of this […] people came in. And afterwards the room was packed”. Embodying a new way to interact with each other can support a group in overcoming established conventions.

Processual level

Working at the processual level has the objective of facilitating knowledge co-production in the advisory setting, once the conditions of a more trusting and collaborative atmosphere have been created. Our second argument is that:

-

2.

Process expertise encompasses the capacity to co-design a collaborative process, by structuring and supervising the co-production of knowledge of multiple actors.

A researcher describes such an intervention as “advising on the process”: “we […] help shape a path that can lead to a solution, although we can’t see the solution ourselves”. Similarly, Lee, in her analysis of public engagement professionals practice, underlines their focus on the “quality and integrity” of the process (2015, pp. 90–92). Researchers’ advice offers a “structure” to the dialogic interaction, leading towards co-production of knowledge and the co-design of a collaborative process. The way they describe their knowledge on process design (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Bryson et al., 2013; Kadlec and Friedman, 2007; Purdy, 2012) suggests a mental map that guides their understanding of collaborative processes. This map includes, for instance, an established and tested “question-set”, as one of the researchers called it: “Who do you need to engage, on which issue, and how? And why is this collaborative arrangement actually necessary?” These questions lay the focus on the essential ingredients for collaboration to take place. Constantly connecting the co-production of ideas of the group with the identified purpose of the assignment is a further element of this mental map (“you always need these learning loops to check: wait, does this still serve the original purpose [of the collaborative arrangement]?”). Researchers speak of the co-design of new interaction orders as an ongoing process of “divergence” and “convergence”, borrowing an expression often used in the facilitation community of ‘The Art of Hosting’Footnote 3. In the former, participants are invited to develop new ideas and perspectives on the issue, while in convergence phases researchers attempt to operationalise discussions into workable action plans: “At some point I just tried to ask the classic questions […] and to bring some structure to the conversation so that people can work a little more consciously with: What is possible in this context? What are the next steps? And also: Who is actually taking care of the implementation of these steps?” The co-production of knowledge is thus condensed into concrete prototypes, plans, strategies, and responsibilities. The researchers’ intervention does not end at the design of the collaborative arrangement in the backstage; instead, they supervise its implementation and unfolding over time at the frontstage. Molinengo and Stasiak describe the practice of “supervising” as the attempt by process experts to guide or adjust the original design of the collaborative arrangement according to the dynamics that emerge during its implementation (2020, p. 6407). This is exemplified by a team member who reports that, while implementing a series of citizen councils, their work consisted of providing backstage support for the conveners from the public administration: “Here I often had the role of […] working with other people [public servants] to ensure that the agreed path is being followed and the set goals are being pursued”. In the implementation phase, the mental map and its defined goals and activities provide orientation for researchers to supervise and potentially adjust future paths.

Skills involved in process expertise

In order to analyse the sources of process expertise, we first investigated the individual skills of team members. In the course of analysis, however, we realised that teamwork also actively contributed to the development of process expertise. Hence, we propose our third argument:

-

3.

Process expertise is cultivated, fostered, and implemented not only at the individual level but also within the team—as a collective practice to advance researchers’ advisory work.

Individual practice

The research team has six members: five with an academic background in social sciences (political sciences, sociology, public administration studies, and applied linguistics) and one physicist. Such diverse academic training is very useful while offering advice. One example is training in “systematic listening”: “where you really try to understand the perspective of the other person. […] what kind of problem do they actually have to solve, these politicians? My impression is that they usually can’t even formulate that themselves. But you can try to support it by listening”. Similarly, analytical skills can contribute to identifying crucial, but as yet unaddressed, dimensions of the problem in dialogue with the counterpart (“[you] can spot where it’s going to get difficult, where social conflicts might occur or just the process doesn’t make sense anymore”). Skills acquired via academic training and research are complemented in the team by experience in advocacy and facilitation work. Past collaborations with politicians and public servants, for instance, allow researchers to better understand the modus operandi of the policymaking world. Competence in the fields of collaborative leadership, agile project management, and facilitation (including approaches such as Art of Hosting, Design Thinking, Dynamic Facilitation, Process Work and Deep Democracy) is also of much practical value in this realm. For instance, “thinking in prototypes” is mentioned by several researchers as a key ability, helping to translate abstract ideas into tangible suggestions that come across in the exchange with policymakers. Individual dispositional attributes, as also highlighted in the facilitation literature (Lee, 2015), contribute to fine-grained relationship-building skills: “When you start explaining things […] (said a researcher to a colleague in the collective reflection session) it is very […] inviting because of your gestures, because of the way your eyes light up. […] [In this way you can] connect to people very quickly”. Another researcher highlighted how a colleague’s way of positioning himself towards the counterpart with “a deep respect, although you might not share their position” allowed interlocutors to share their perspective without feeling judged or criticised. One can thereby make others “feel valued […] [in the] knowledge they possess”. Furthermore, researchers seemed to have specific attitudes while performing their advisory function. One researcher reflected on his reaction to statements such as: “no, this is not possible” which he often heard from policymakers. “I deliberately hold on to the belief that governance processes are human-made. And this means that it is possible for us to design them differently, [and that] we define the rules of the game.”

Team practice

Although researchers’ individual skills underpin process expertise, the analysis reveals that it is also cultivated, fostered, and—above all—implemented as a collective practice within the team. The interviews referred to “teamwork”, namely the ability of engaging in and fostering collective practice, as “a precondition” for many of the research group’s activities. The team was described as the place where researchers support each other in the strategic planning of advisory processes, “to make a reflected proposal to the outside world”. “[A] clarifying process arises in the team […] where the other team members […] point out potential challenges [connected to the specific context] or come up with new ideas”. These ritualised spaces for exchange differ from conventional peer-to-peer mechanisms in research practices. Here, those individual skills identified in the previous section are practiced within the team with the goal of contributing to the architecture of advisory processes. Such open communication among researchers relies on a shared set of basic distinctions acquired in the team’s practice over the years (Schön, 1983, quoted in Yanow and Tsoukas, 2009) since its foundation in 2017. Starting the week with a 30-min meeting in which each member updates the others on their upcoming tasks, plus a moderated 2-h meeting mid-week, allow the six members to maintain an overview of the team activities, to efficiently make decisions, share with their colleagues the current challenges of their advisory work, and co-develop strategies to tackle them. The practice of process expertise—seen by the team as crucial to running its activities—is explicitly trained and reflected upon during these meetings. Furthermore, including the elements of agile (Morrison et al., 2019) and strengths-focused (Clifton and Harter, 2003) approaches in leading the team, as well as balancing the orientation towards effectiveness and relationships (Kahane, 2010) encourages the proactivity of its members, stimulates collaboration instead of concurrence, and fosters co-ownership of the research agenda. As one of the researchers framed it: “I wonder if you can even be a single ‘process expert’. I feel it’s definitely a collective process to enact process expertise. […] [It is] a collective capacity, instead of owning a set of skills as an individual and then bringing it to others. […] it is a situated collective experience.”

Practicing process expertise in a collective manner is particularly relevant given that their work takes place in volatile contexts such as policymaking: “on a terrain that is often fragile […] so that my intervention today may no longer be appropriate tomorrow”. This implies a higher “risk” for researchers and may have consequences for their academic activity, given the fact that research timelines and lists of publications do not make an exception for collaborative research approaches (Bennett and Brunner, 2020, p. 13): “you have to take into account that you may not deliver results very quickly, for example. Or that the original plan may blow up. […] Anything can happen.” These observations relate to the argument of Balmer and colleagues, that “taking risks” is a core element of collaborative work in research (2015, p. 20). During the team discussion, the issues of “courage” and “risk-taking”, necessary to work as researchers in such settings, came up several times. Courage was connected to fears of practicing something unusual, within both the policymaking and academic worlds, while teamwork, again, was seen as crucial for coping with risk: “I don’t think that anyone is born a coward, you know [laughs]; I think it has a lot to do with trust and a feeling of confidence—not in yourself but in the situation and also in others in the situation. […] imagine we would just have this sort of group where we feel so at ease that we can take risks […] then I think courage can grow even more, you know […] courage can be a product of collaboration. […] it’s something that you can create”. The team practice, both in terms of co-producing new ideas and generating a solid basis of trust among members, appeared very supportive for the researchers’ work in advisory settings.

Process expertise in “in-between spaces”

Limiting the analysis of process expertise to the individual skills and its team practice would be insufficient to cover its unfolding in relation with policymakers. Building on Eyal and Pok’s definition of expertise as an “in-between space” connecting different arenas (2015, pp. 41–42), we develop our fourth argument:

-

4.

Process expertise unfolds in the interaction among actors and contributes to generating a space between research and policymaking, where new interaction orders emerge.

The analysis of the research team’s advisory activities shows that accessing the policymaking backstage of collaboration can take place in different ways and is often linked to windows of opportunity. In the advisory activity around tackling mobility challenges raised by the pandemic, pre-existing trusted relationships with policymakers—established by the long-term immersion in the field of a team member through their research and advocacy activities—generated the basis for quickly joining forces. In the activity on implementing citizen councils at municipal level, engaged citizens who had heard about this participatory methodology approached an IASS researcher with a reputation and theoretical expertise in this domain, seeking support in presenting a proposal to the district mayor. In a third possibility—as in the case of the coal phase-out in the Lusatia region—IASS researchers actively integrated policy advice activities into their research strategy at project outset and sought interested partners at the policymaking level during the research design phase. What connects all these activities is what researchers refer to in the interviews as the “exploratory phase”, or “phase zero”, as conceptually formulated by one of them (Herberg, 2020). It is in this phase, at the outset of the advisory process, that researchers actively facilitate an enquiry process for both parties—researchers and policymakers—to discuss the object of collaboration, (re-)frame the problem to be tackled, get to know the counterparts’ resources, identify interdependencies, define roles and tasks, and verify their own motivation and interests. This lays the foundation for each actor to identify their own collaborative advantage (Huxham, 1996) and decide upon their participation in this advisory space. In phase zero, researchers facilitate and structure the exchange by “influencing from the very beginning the dialogic setting”, both at the relational and processual level. By asking specific questions to the interlocutor, researchers move beyond their own knowledge and experience, to sharpen and identify the very challenge to be tackled. With researchers’ support, policymakers “explore, map and expand their understanding of the complex problem space before the political institution or decision-making body sets transformative change in train” (Bruhn et al., 2019, p. 336). It is through this experience that policymakers may acknowledge the value of process expertise and grant access to backstage settings: “Initially, we [researchers] were only asked to give an idea of how it [collaborative process] might look. But then we had so many questions that they [policymakers] said: Well, we could actually appoint this institute for this [assignment]”. In the setting where process expertise operates, both researchers and policymakers constantly check whether the issue, and the approach chosen to tackle it, cover their own agenda. Indeed, the willingness of both researchers and policymakers to participate is an essential precondition for this space to exist. A researcher describes this mutual exploration of expectations as “trying to find out: they [policymakers] are approaching us with an initial assignment: is this really the core aspect of the issue we could contribute to, or is there more behind it? And […] it is also about finding out: does this request match what we can and want to offer?” The statement highlights the difference between the roles of researchers and corporate actors in these advisory processes. Private consultants’ assignments and goals are set by the client, whereas researchers are usually not bound by contracts with policymakers: “We are not financially dependent on someone else. […] It’s more like […] getting to know each other and starting to think together about what could actually emerge [out of this collaboration].” In this way, the encounter between advisors and policymakers goes beyond the rules and etiquettes of the policymaking backstage. The actors meet in neither the academic nor policymaking field, but instead “in-between”. Along with the development of cooperation, a permeable and weakly institutionalised (Eyal and Pok, 2015, p. 44) space starts taking shape between researchers and policymakers, with new interaction orders fostering knowledge co-production and mutual learning. Distinct perspectives can co-exist, while the actors’ differing forms of expertise intertwine with each other: “And that is perhaps also […] the co-creative aspect about it [this operating modus]. You can work together on something, even if you have different goals. You might be ‘paid out’ in different kinds of ‘currencies’, contribute with different resources and have different criteria of success. But somehow you can still identify a common intention that keeps you together and leads you to unite forces”. In such an in-between space, expertise does not simply flow from advisors to policymakers. Rather, different kinds of expertise interact with each other and generate diverse outputs, both at a policymaking and research level.

Process experts as an assemblage

Eyal and Pok (2015, p. 49), quoting Callon (2005), propose seeing experts as an “assemblage” shaped by “all those actors—humans as well as non-human devices—who participate in putting together statements and performances without being authorised to speak or act”. In other words, researchers can exercise their process expertise in advisory settings via a set of specific conditions. Our fifth argument in this regard is that:

-

5.

Process expertise is exercised by researchers through an assemblage of enabling conditions supported by their status as academics.

Understanding experts as an “assemblage” allows us to critically reflect on what enables researchers to take on the position of process experts. The first and main enabling condition refers to their academic status, and its related cognitive authority (Escobar et al. 2014, p. 98), which grants them a privileged role while accessing the policymaking backstage: “the fact that I am an academic and I can perform as such gives me, from time to time, a sort of more neutral and credible role of…an expert”. Team members showed high awareness of not being neutral in these processes (“I’m an actor when I’m […] advising […] because I’m shaping those settings in a certain way.”). Paradoxically, it is particularly this alleged “neutrality” as academics that grants them the position of experts and allows them to have a substantial role in these processes (Balmer et al., 2015, p. 9). It allocates “a sort of catalytic power. You can give space to particular voices and invite others to listen. […] You can bring those people that are not present in the room into the conversation”. While this engenders advantages, it also increases the responsibility of researchers to be aware of the power dynamics in the room, including the power vested in their own role. Financial independence from policymakers is another condition that enables researchers to act more freely than other consultants: “If I were a freelancer […] I would probably act differently […] I would have to advise while knowing: Okay, I can sell this in the end.” This aspect calls for transparent and open relations: “This is an invitation. Anyone can profit from it. I am open to working together with anyone [that is interested]”. A third enabling condition in such settings is the relatively unconstrained time frame, and access to diverse kinds of knowledge. Long-term immersion in their field allows researchers to engage with a multitude of perspectives and legitimises them to ask questions that other actors might not be willing to pose: “in conflict situations […] [you are] in a very privileged position because you listened very broadly, and this is definitely a societal resource that you can bring in”. However, wielding such societal resources leads researchers toward a greater awareness of their own role in the political sphere. As one researcher puts it: “This really is a luxury, I have to say. But it [the status of researcher] also comes with a particular duty [towards society]”.

Discussion

Our results show that process expertise, when exercised by researchers and supported by an assemblage of enabling conditions inherent to the research context (finding 5.), goes beyond the possession of a set of skills at the individual level (finding 3.). Instead, process expertise fulfils its task, namely the co-design of a tailor-made strategy for different actors to collaborate with each other on a specific issue, by generating an “in-between space” where process expertise unfolds in interaction with other types of knowledge and new interaction orders among actors can emerge (finding 4.). In this realm, relational work contributes to establishing a collaborative modus operandi at the very outset of the advisory process (finding 1.), while working at the processual level structures and supervises the co-production of knowledge of multiple actors (finding 2.). This perspective on process expertise resonates with the distinction proposed by Cook and Brown (1999) between an epistemology of possession, which treats “knowledge as a distinct, self-sufficient entity that individuals and groups can possess, share, pass on, acquire, lose and recover” (Marshall and Rollinson, 2004, p. 73 on the work of Cook and Brown, 1999) and an epistemology of practice, which proposes “a view of knowledge as a dynamic, negotiated, situated, social accomplishment” (Marshall and Rollinson, 2004). Process expertise, in our context, can best be understood if analysed under both perspectives. On the one hand, our results show that with respect to the content of expertise (Garrett et al., 2009) researchers in advisory settings possess sophisticated knowledge on process design necessary to plan any collaborative arrangement. The exercise of this core competence alone, however, does not suffice to complete such a task and is complemented by other competencies that support the process by which this content knowledge is applied to a specific case: researchers’ analytic skills acquired via academic training support policymakers in exploring and expanding their understanding of the complex problem space (Bruhn et al., 2019, p. 336) to be addressed; facilitation skills contribute to structuring the process of co-production of knowledge among involved actors. These skills do not directly relate to the problem at hand (Bammer et al., 2020, p. 2) but rather focus on generating the conditions for different actors to work together in tackling the problem. From this perspective, process expertise is best illustrated from a practice view: researchers engage with other kinds of knowledge in the room and use their own expertise to create an arena of productive interaction. Ultimately, similarly to the invisible role of facilitators described by Lee (2015, p. 114), participants engaged in the co-production process might find it difficult to clearly identify researchers’ contributions.

Since the very beginning of “phase zero”, process expertise contributes to generating a new operational context, which is to be found neither in the academic nor policymaking field, but instead “in-between”. In this permeable and weakly institutionalised (Eyal and Pok, 2015, p. 44) space, all actors involved are invited to step out of their conventional roles into an unknown zone (“Zonen der Uneindeutigkeit”: Felt, 2010, p. 77). Such fluidity of actors’ roles constitutes the greatest strength of these spaces, as it enables the emergence of new communicative dynamics that pave the way for knowledge co-production. At the same time, these spaces are temporary, fragile, and volatile: In the worst case, a single personnel change or withdrawal among the policymaking counterparts may jeopardise all collaborative and research efforts. Also, working in such spaces can require substantial time investments from researchers, possibly leading to an imbalance between their tasks as advisors and scientists. Ongoing effort is needed to cultivate these spaces for policymakers and researchers, to keep engaging within these settings. Bennett and Brunner, who introduce the concept of a buffer zone, that is “[…] a space, a border zone between multiple worlds of work within which new political and relational work occurs” (2020, p. 14) in collaborative research practices, argue that work at the relational level (Bennett and Brunner, 2020, p. 15) is essential for creating and sustaining such practices with non-academic partners (see also Westling et al., 2014, p. 443). Next to the relational level, we identify a further contribution of process expertise: its work at the processual level. It is at this level that collaboration shows its productive side and generates tangible results. For instance, in the advisory activity to co-develop safe mobility strategies at the early stages of the COVID 19-pandemic, researchers’ relational work intertwined with an ongoing generation and testing, together with the other actors, of prototypes (e.g. temporary play streets) to address the set challenge. The interplay between collaborating and experiencing the results of this collaboration fostered the active engagement of actors within this arena and their motivation to be part of it. In the case of the Lusatia region, the researcher’s facilitation of new connections among backstage and frontstage actors led to the co-development of a collaborative strategy, thus strengthening the mandate of this advisory space. We therefore argue that it is the ongoing work of process expertise at the intersection of relational and processual levels that helps maintain momentum in collaborative partnerships.

Furthermore, we identified two factors that instil “courage” in researchers to exercise process expertise as an integral part of their research mandate in these contexts and that support maintaining these settings. First, the collective practice of process expertise in the research team’s weekly meetings, where members experiencing challenges with an advisory activity can turn to their colleagues, plays a crucial role in offering peer-to-peer consultation. Also, through reflection, these meetings generate some critical distance to the pressuring demands of the policymaking field (Boezeman et al., 2014), while encouraging a balance between societal and research outcomes. A second factor is to be found at the research institutional level. The IASS research approach (Meisch, 2020; Nanz et al., 2017) grants a mandate for the research team to experiment with such emerging research practices and holds an awareness of the soft skills (e.g. experience in collaborative leadership, facilitation, and agile management) necessary for collaborative research work when recruiting from academic personnel for these activities. Also, funding that goes beyond short-term third-party projects provides significant capacity, in terms of both monetary and human resources, for supporting these emergent advisory practices (Kennedy, 2018); it guarantees researchers’ autonomy from (while at the same time enabling to establish a productive relation with) their counterparts in these spaces; it offers research teams great freedom in identifying fruitful partnerships, while avoiding projects with co-optation risks; and, most importantly, it allows relatively stable team composition, which is crucial for cultivating a team practice.

Process expertise deserves further scrutiny and reflection. The reflection-in-action approach of the present study has highlighted some of the challenges arising in this advisory practice. Although an in-depth discussion of the advantages and pitfalls of engaged scholarship in advisory practice goes beyond the scope of the present paper, substantiating the practical challenges with insights from other, more critical, academic discourses would be a logical further step. Potential paths to strengthen the robustness of our findings could include extending the analysis to other research teams with a similar mandate; investigating policymakers’ perceptions of researchers’ work in this setting; and analysing the impacts of collaborative arrangements co-designed by researchers and policymakers.

Conclusion

In this paper, we attempt to give a language to the “invisible work” (Bennett and Brunner, 2020, p. 13) performed by researchers who offer policymakers—and other invited actors—advice on the process of designing collaboration in collaboration. Process expertise has the potential to enrich the repertoire of “appropriate concepts” that illustrate the complex work that is required in research collaborations (Bennett and Brunner, 2020, p. 13) when tackling complex socio-environmental challenges. This expertise, as we show, goes beyond mastering a specific method: it consists of a combination of dispositional elements (such as the character and biographical experiences of individual researchers) and—to a larger extent—learnable skills. These skills are not restricted to a single domain (e.g., facilitation work), but extend to a broader set of practices that rely on the experiences of researchers in different contexts (academia; private sector; NGOs; policymaking). Furthermore, this learning process is accelerated and fostered when embedded in the collective practice of a research team and should be seen as ongoing and lifelong.

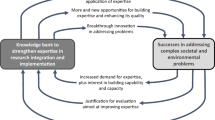

How to learn from and further improve practices of process expertise of academic communities involved in research integration and implementation across various contexts? One approach is to share advisory experiences. A first step in this direction is Bammer et al.’s (2020) proposal of building a shared knowledge bank of expertise. While we endorse documenting and connecting expertise, we also see much value in cooperation and exchange at the level of practice, and hence learning (from each other) by doing. Building a network of research teams—working in advisory contexts with process expertise—could offer guest researchers an opportunity to participate in local policy advice activities and exchange practices ‘in situ’. Also, while the main focus of this study was the role of process expertise in establishing invited spaces (Cornwall, 2002) for collaboration, the potential of this kind of expertise clearly extends beyond such formalised settings. Researchers’ skills in establishing legitimate collaborative processes and relations among different actors could be of even greater value in conflictual and contested contexts. Being able to offer advice not only to policymakers, but also, e.g., to citizen groups who not only invent but also claim new spaces for meaningful participation, turns out to be increasingly relevant (Gaventa and Cornwall, 2008, p. 186). Further structured reflection on and deliberate development of process expertise is necessary for science to realise its transformative mandate in a responsible and transparent manner.

Process expertise is already practiced across various contexts. While we hinted at some of the key elements of process expertise, these are to be understood not as a prescription but as an invitation to a further conversation with interested communities of transformative scholarship. Fostering such an exchange appears important not only for the theoretical refinement of process expertise as a concept, but primarily in terms of support and orientation for researchers facing the challenges of collaboration on a daily basis. In this context, the practice evolves much faster than the theory; our reflection-in-action approach has offered a way to bring them into dialogue.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available because they include sensitive information concerning specific advisory processes and actors, but are available (in anonymised form) from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Jarass and von Schneidemesser (2021).

In the “Results” section, text quoted from the empirical material is indicated by “italics and quotation marks”.

https://www.artofhosting.org/. Accessed 5 Nov 2021.

References

Ansell C, Gash A (2008) Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J Public Adm Res Theory 18(4):543–571.

Asenbaum H (2020) Facilitating inclusion: Austrian wisdom councils as democratic innovation between consensus and diversity. J Public Deliberation 12(2):1–11. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.259

Aubin D, Brans M (2021) Styles of policy advice: a typology for comparing the standard operating procedures for the provision of policy advice. In: Howlett M, Tosun J (eds.) The Routledge handbook of policy styles. Routledge, pp. 286–299

Balmer AS, Calvert J, Marris C et al. (2015) Taking roles in interdisciplinary collaborations: reflections on working in post-ELSI spaces in the UK synthetic biology community. Sci Technol Stud 28(3):3–25. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.55340

Bammer G, O’Rourke M, O’Connell D et al. (2020) Expertise in research integration and implementation for tackling complex problems: when is it needed, where can it be found and how can it be strengthened? Palgrave Commun 6(5):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0380-0

Bandola-Gill J, Lyall C (2017) Knowledge brokers and policy advice in policy formulation. In: Howlett M, Mukherjee I (eds.) Handbook of policy formulation. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, Northampton, USA, pp. 249–264

Barley WC, Treem JW, Leonardi PM (2020) Experts at coordination: examining the performance, production, and value of process expertise. J Commun 70(1):60–89. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqz041

Becker KL, Renger R (2017) Suggested guidelines for writing reflective case narratives. Am J Eval 38(1):138–150. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214016664025

Bennett H, Brunner R (2020) Nurturing the buffer zone: conducting collaborative research action in contemporary contexts. Qual res 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120965373

Berger R (2015) Now I see it, now I don’t: researcher’s position and reflexivity in qualitative research. Qual Res 15(2):219–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112468475

Blaikie NWH, Priest J (2019) Designing social research: the logic of anticipation, 3rd edn. Polity Press, Cambridge

Bobbio L (2019) Designing effective public participation. Policy Soc 38(1):41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2018.1511193

Boezeman D, Vink M, Leroy P et al. (2014) Participation under a spell of instrumentalization? Reflections on action research in an entrenched climate adaptation policy process. Crit Policy Stud 8(4):407–426. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2014.950304

Brand R, Karvonen A (2007) The ecosystem of expertise: complementary knowledges for sustainable development. Sustainability 3(1):21–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2007.11907989

Bruhn T (2017) On the culture of untapped potential. Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam. https://www.iass-potsdam.de/en/node/5573 Accessed on 5 November 2021

Bruhn T, Herberg J, Molinengo G et al. (2019) Frameworks for transdisciplinary research #9. GAIA 28(4):336. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.28.4.3

Bryant A, Charmaz K (eds.) (2007) The sage handbook of grounded theory. SAGE Publications, London

Bryson JM, Quick KS, Slotterback CS, Crosby BS (2013) Designing public participation processes. Public Adm Rev 73(1):23–34. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02678.x

Callon M (2005) Disabled persons of all countries, unite! In: Latour B, Weibel P (eds.) Making things public: the atmospheres of democracy. MIT Press, Cambridge, pp. 308–313

Carrozza C (2015) Democratizing expertise and environmental governance: different approaches to the politics of science and their relevance for policy analysis. J Environ Policy Plan 17(1):S. 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2014.914894

Chilvers J (2008) Deliberating competence. ST&HV 33(3):421–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907307594

Clifton DO, Harter JK (2003) Investing in strengths. In: Cameron AKS, Dutton BJE, Quinn CRE (eds.) Positive organizational scholarship: foundations of a new discipline. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco, pp. 111–121

Colebatch HK (2006) What work makes policy? Policy Sci 39(4):309–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-006-9025-4

Collins H (2014) Are we all scientific experts now? Polity Press, Cambridge

Collins H, Evans R, Weinel M (2016) Expertise revisited, Part II: Contributory expertise. Stud Hist Philos Sci 56:103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shpsa.2015.07.003

Connaughton B (2010) ‘Glorified gofers, policy experts or good generalists’: a classification of the roles of the Irish ministerial adviser. Irish Political Stud 25(3):347–369. https://doi.org/10.1080/07907184.2010.497636

Cook SDN, Brown JS (1999) Bridging epistemologies: the generative dance between organizational knowledge and organizational knowing. Organ Sci 10(4):381–400. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.10.4.381

Cooper E, Smith G (2012) Organizing deliberation: the perspectives of professional participation practitioners in Britain and Germany. J Public Deliberation 8(1):3. https://doi.org/10.16997/jdd.125

Cornwall A (2002) Making spaces, changing places: situating participation in development. IDS, Brighton

De Donà M (2021) Matching institutionalized expertise with global needs: boundary organizations and hybrid management at the science–policy interfaces of soil and land governance. Environ Sci Policy 123:82–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2021.05.015

Dillard KN (2013) Envisioning the role of facilitation in public deliberation. J Appl Commun Res 41(3):217–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/00909882.2013.826813

Escobar O (2014) Transformative practices: the political work of public engagement practitioners. Dissertation, University of Edinburgh

Escobar O, Faulkner W, Rea HJ (2014) Building capacity for dialogue facilitation in public engagement around research. J Dialogue Stud 2(1):87–111 http://www.dialoguesociety.org/publications/academia/944-journal-of-dialogue-studies-vol-2-no-1.html

Escobar O (2015) Scripting deliberative policy-making: dramaturgic policy analysis and engagement know-how. JCPA 17(3):269–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2014.946663

Escobar O (2019) Facilitators: the micropolitics of public participation and deliberation. In: Elstub S, Escobar O (eds.) Handbook of democratic innovation and governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 178–195

Eyal G, Pok G (2015) What is security expertise? From the sociology of professions to the analysis of networks of expertise. In: Berling TV, Bueger C (eds.) Security expertise. Practice, power, responsibility. Routledge, London, pp. 37–59

Eyal G (2019) The crisis of expertise. Polity Press, Cambridge, Medford

Felt U (2010) Transdisciplinarity as culture and practice. GAIA 19(1):75–77. https://doi.org/10.14512/gaia.19.1.17

Felt U, Fochler M (2010) Machineries for making publics: inscribing and de-scribing publics in public engagement. Minerva 48(3):219–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11024-010-9155-X

Fischer F (2000) Citizens, experts, and the environment. Duke University Press, Durham

Fischer F (2003) Reframing public policy: discursive politics and deliberative practices. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fischer F (2009) Democracy and expertise: reorienting policy inquiry. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fischer F (2012) Participatory governance: from theory to practice. In: Levi-Faur D (ed.) The Oxford handbook of governance. Oxford University Press, pp.1–16

Flyvbjerg B (2006) Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual Inq 12(2):219–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800405284363

Follett MP (1930) Creative experience. Longmans Green and Co., New York, London

Forester J (2013) On the theory and practice of critical pragmatism: deliberative practice and creative negotiations. Plan Theory 12(1):5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095212448750

Freeth R, Vilsmaier U (2020) Researching collaborative interdisciplinary teams: practices and principles for navigating researcher positionality. Sci Technol Stud 33(3):57–72. https://doi.org/10.23987/sts.73060

Galison P (2010) Trading with the enemy. In: Gorman, ME (ed.) (2010) Trading zones and interactional expertise: creating new kinds of collaboration. The MIT Press, pp. 25–52