Abstract

Due to the rapid spread of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) worldwide, most people have been forced to alter their lifestyles. This situation may affect the mental health of individuals through the disruption of core beliefs about humans, the world, and the self. Therefore, in this study, an online survey of Japanese adults was conducted to investigate the associations between subjective achievement and the burden of cooperation in preventive measures, disruption of core beliefs, and psychological distress. The results showed that pandemic-induced disruption of core beliefs occurred at a relatively low level in the general population of Japan. In addition, the achievement and psychological burden of preventive measures, reduced income due to the pandemic, and stressfulness of the pandemic were significantly associated with the level of the disruption of core beliefs. Moreover, the greater the disruption of core beliefs, the greater the psychological distress. These findings indicate that the violation of fundamental assumptions about life are an important factor determining mental health during a pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since the first infected patient was detected in Wuhan, China in December 2019, the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has expanded rapidly worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) declared the outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020 (WHO, 2020). The psychological impacts of COVID-19, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and sleep disturbances have been reported in both healthcare workers and the general population, and many systematic reviews and meta-analyses have been published over the last 18 months (Salari et al., 2020; Luo et al., 2020; Krishnamoorthy et al., 2020; Xiong et al., 2020; Cénat et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2021; Nochaiwong et al., 2021; Marvaldi et al., 2021).

Unpredictability and uncontrollability during pandemics may be one of the reasons for mental health problems (Zandifar and Badrfam, 2020). People are being exposed to volatility and uncertainty in the world during the COVID-19 era (Noda, 2020). It is suggested that people who experience a largely irreversible change in society and lifestyle due to pandemic may reconsider what is most important to themselves, discover new aspects of themselves, and gain spirituality (Yamaguchi et al., 2020; Noda, 2020). Such reconsiderations are referred to as the “disruption of core beliefs” (Janoff-Bulman, 1989; Cann et al., 2010; Ramos and Leal, 2013). Core beliefs are components of the fundamental assumptions about human behaviour, the unfolding of events, and one’s own ability. For example, human beings are basically “benevolent”/“malevolent,” “adversity will not happen to a person who behaves ethically and correctly”/“adversity will fairly happen to everyone,” and oneself is “worthy”/“worthless” (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). People usually behave unconsciously based on such beliefs, after which they are empirically constructed (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). However, if an event that cannot be explained by fundamental assumptions occur, core beliefs can be disrupted, and the need for re-examination arises (Janoff-Bulman, 1989). The disruption of core beliefs has been reported to occur as a function of serious illness (Cann et al., 2010; Danhauer et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2014; Ramos et al., 2018), military experience (Morgan and Desmarais, 2017), terrorism (Eze et al., 2020), and natural disasters (Zhou et al., 2015; Taku et al., 2015). Core belief disruption is a significant predictor of post-traumatic growth (Cann et al., 2010; Danhauer et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015; Taku et al., 2015; Morgan and Desmarais, 2017; Ramos et al., 2018; Eze et al., 2020), but it also correlates with post-traumatic stress symptoms (Zhou et al., 2015), the stressfulness of the event (Taku et al., 2015), and negative mood (Cann et al., 2010).

In Japan, the government announced a state of emergency in April 2020 for the first time during this pandemic. The first wave of the outbreak was relatively contained in about a month, and the state of emergency was lifted for all of Japan in May. Although the number of cases and deaths has been lower than those in Western countries (Idogawa et al., 2020), psychological distress in the general population was reported in Japan (Kikuchi et al., 2020, 2021; Fukase et al., 2021; Yoshioka et al., 2021; Nagasu et al., 2021). Age, gender, the financial situation, and marital status have been identified as factors associated with severe psychological distress (Fukase et al., 2021; Nagasu et al., 2021; Yoshioka et al., 2021), but the association between these variables and core belief disruption due to pandemics is unknown. Since Japanese law does not allow for lockdown during pandemic, the degree of cooperation in preventive measures is left to the initiative and cooperativeness of the people. It is also unclear how an individual’s level of cooperation and burden with preventive measures is related to the disruption of core beliefs and psychological distress.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to clarify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on core beliefs among the general population in Japan. We investigated the association between demographic characteristics, the level of cooperation and burden of preventive measures, core belief disruption, and psychological distress in Japanese adults.

Methods

Participants

A total of 11,035 individuals were recruited through Cross Marketing Inc., and 1,200 people finally completed the online survey. The age range of these individuals was 30–79 years. Potential participants received an invitation email for the survey; all respondents were survey panel of Cross Marketing Inc. Individuals who completed the questionnaires were rewarded with cashable coupons. Four respondents confirmed themselves or a member of their family to be infected with COVID-19 and their data were consequently excluded from the statistical analysis; thus, the data of 1196 participants were finally included in this study.

It is possible that differences in the number of COVID-19 patients across residential areas affect the statistical results. Thus, using the mean number of cases per one million population during the period from March 11, 2020, when the pandemic was declared by WHO, to May 25, 2020, when the state of emergency was lifted in Japan as a reference (Idogawa et al., 2020), we selected Tokyo and Sendai as the regions to be surveyed. During that time, Tokyo had the highest number of cases per one million people in Japan (more than 190). Sendai is the prefectural capital of Miyagi prefecture, which is one of the areas where the number of cases per million population was less than 30.

Measurements

Demographic variables

As demographic variables, participants were asked to identify their age, sex, prefecture of residence (Tokyo or Sendai), marital status (married [including divorced or bereaved] or unmarried), school closures of child (experienced or not experienced), and changes in income due to the pandemic (significantly decreased, decreased, not changed, increased, or greatly increased).

Achievement and psychological burden of preventive measures

Participants were asked two original questions to assess the subjective level of achievement and psychological burden in cooperation with preventive measures during the state of emergency; the first one was “To what extent do you think you have cooperated with preventive measures such as avoiding unnecessary outings, during the state of emergency?”, and the other one was “To what extent do you think you have had felt a burden in cooperating with preventive measures such as avoiding unnecessary outings, during the state of emergency?” Responses to these two questions were given using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely).

Disruption of core beliefs

We used the Japanese version of the Core Belief Inventory (CBI) to assess the level of the participants’ disruption of core beliefs. The CBI is a nine-item scale developed by Cann et al. (2010) that is used to assess the extent of the disruption and re-examination of individual core beliefs due to a particular event. The Japanese version was developed by Taku et al. (2015), and its reliability and validity have been confirmed (Taku et al., 2015). Our participants were required to identify the extent to which the COVID-19 pandemic had led them to seriously examine their core beliefs. Responses were rated on a six-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (to a very degree). The internal reliability of the CBI in the current study was sufficient (Cronbach’s α = 0.945).

Stressfulness of the pandemic

As prior studies have reported that the level of disruption of core beliefs is influenced by the stressfulness of the event (Taku et al., 2015), we used an original question item that asked participants about the stressfulness of the spread of COVID-19: “To what extent have you felt stressed about the spread of COVID-19?”. Responses to this question were given using a visual analogue scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 100 (extremely).

Psychological distress

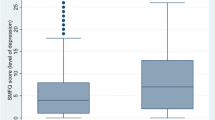

The Japanese version of the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale (K6) was used (Kessler et al., 2002; Furukawa et al., 2008). The K6 is a six-item scale that assesses psychological distress in the previous month. Responses were rated on a five-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (always).

Statistical analysis

Multiple regression analysis with stepwise method was used to examine the factors associated with the disruption of core beliefs due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The total CBI score was entered as an independent variable. Participants’ age, sex, prefecture of residence, marital status, school closures of child, changes in income due to the pandemic (we integrated participants who selected “significantly decreased” or “decreased” into “Reduced,” “not changed,” “increased,” or “greatly increased” into “Not reduced.” “Reduced” was dummy coded as 1, and “Not reduced” was dummy coded as 0), the achievement of preventive measures, the psychological burden of preventive measures, and the stressfulness of the pandemic were entered as dependent variables. The most appropriate model was selected using the Akaike information criterion (Akaike, 1998). Subsequently, a path analysis was conducted to examine the association between psychological distress, disruption of core beliefs, and predictive factors of the disruption of core beliefs, as detected by the multiple regression analysis. The appropriate model was selected based on the following fit indices criterion: comparative fit index (CFI) > 0.95, Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95, standardized root mean square residuals (SRMR) < 0.08, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06. The statistical significance level was set at P < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using RStudio version 1.2.5042.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for all the study variables. The mean values and standard deviations of the answers for each question item regarding the disruption of core beliefs are described in Supplementary Table S1.

Prediction model of the disruption of core beliefs

As a result of the multiple regression analysis, the psychological burden of preventive measures, the achievement of preventive measures, changes in income due to the pandemic, and the stressfulness of the pandemic were found to have significantly and positively predicted the level of the of disruption of core beliefs (the total CBI score; Table 2). Multicollinearity was not detected because the variance inflation factors (VIF) for each of the four variables were < 2. Participants’ age, sex, prefecture of residence, marital status, and school closures of child were excluded from the prediction model as they failed to reach statistical significance. In addition, multiple regression analyses were conducted in the same way, using the scores for each CBI question item as dependent variables. The results of these analyses are shown in Supplementary Table S2. Briefly, the psychological burden of preventive measures significantly predicted all CBI question item scores.

The significant model confirmed by path analysis

Based on the results of the multiple regression analysis, a path analysis was conducted to investigate the association between the psychological burden of preventive measures, the achievement of preventive measures, changes in income due to the pandemic, the stressfulness of the pandemic, disruption of core beliefs, and psychological distress. First, we examined the model that the psychological burden of preventive measures, the achievement of preventive measures, reduced income due to the pandemic, and the stressfulness of the pandemic predicted the disruption of core beliefs and the disruption of core beliefs correlates with psychological distress; however, this model did not fit the data (CFI = 0.603, TLI = 0.107, SRMR = 0.115, RMSEA = 0.198). We then assumed that psychological distress was also directly predicted by the psychological burden of preventive measures, the achievement of preventive measures, reduced income due to the pandemic, and the stressfulness of the pandemic. The second model fitted the data (CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA < 0.001, SRMR < 0.001). All paths between each variable were significant (Fig. 1, Table 3), with the exception of the path from the achievement of preventive measures to psychological distress (β = −0.001, P = 0.684).

All coefficients are standardized partial regression coefficients. Levels of significance: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05. Burden psychological burden of preventive measures, Achievement achievement of preventive measures, Changes in income changes in income due to the pandemic, Stressfulness stressfulness of the pandemic.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that a higher psychological burden and achievement of preventive measures amid the state of emergency, reduced incomes, and higher stressfulness of the COVID-19 outbreak predict the disruption of core beliefs due to the pandemic. In addition, psychological distress was predicted by the level of disruption of core beliefs, the psychological burden of preventive measures, reduced income, and the stressfulness of the pandemic.

The mean of the total CBI score was 1.35 (SD = 10.23), and the mean per question item ranged from 1.31 to 1.55, except for one item (Q8. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my spiritual or religious beliefs,” mean = 0.81). Prior studies used this scale to investigate the disruption of core beliefs due to serious events such as contracting cancer (Wilson et al., 2014; Ramos et al., 2018), leukaemia (Cann et al., 2010; Danhauer et al., 2013), terrorism (Eze et al., 2020), and earthquakes (Zhou et al., 2015) have reported a mean total score ranging from approximately 2 to 3. According to the developers of the CBI, a mean total score of around 3 represents a moderate level of core belief disruption (Cann et al., 2010). A prior study that assessed the core belief disruption due to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States showed that the mean for the entire sample was moderate, but people who were infected with COVID-19 or who knew someone who had died from COVID-19 experienced a higher disruption of core beliefs (Dominick et al., 2021). Therefore, in the present sample, it seems that core belief disruption due to the pandemic occurred at a relatively low level. This tendency is consistent with the results of a prior study that investigated the disruption of core beliefs among Japanese university students who experienced the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake (mean total CBI score = 1.73) (Taku et al., 2015). The authors of that paper observed that the disruption of core beliefs may be less likely to occur among Japanese people because they tend to view life negatively and believe that tragedies are unpredictable and can happen to anyone (Taku et al., 2015). Thus, it is possible that our findings indicate a general tendency regarding the disruption of core beliefs among the Japanese general public amid the national state of emergency. On the other hand, a previous study examining the disruption of core beliefs among the general population after the 2018 U.S. midterm election reported a relatively low mean of 1.79 (Zhu and Neupert, 2021). Serious illnesses such as cancer are personal life events, and terrorism or natural disasters are events that directly cause physical harm and fear. In contrast, elections may not be so much an experience of fear and trauma, but rather an opportunity to experience the changes in the society in which one lives. Even though there is a fear of infection in this pandemic, it may be an event relatively closer to the latter (election) than the former (illness, natural disaster) for many people. Hence, a low total CBI score of <2 may indicate the general degree of the disruption of core beliefs that occurs in people when social changes occur.

We found that the psychological burden of cooperation with preventive measures was the strongest predictor of the disruption of core beliefs. As mentioned above, the subjects analysed in this study were not infected with COVID-19, so the pandemic may not have been a traumatic event for them. However, it has been suggested that the disruption of one’s core beliefs may occur if an event is stressful and deviates from the individuals’ world assumptions, regardless of what the event comprises (Janoff-Bulman, 1989; Cann et al., 2010). The present pandemic has suddenly altered people’s lifestyles (Noda, 2020). So-called “new normal” lifestyles, represented by physical distancing and avoiding the three “C”s (i.e., closed spaces, crowded places, close-contact settings), could induce a decrease in social interaction and the alteration of daily routines. One qualitative study reported that the loss of social interaction and daily routine has led people to lose motivation, meaning in life, and self-worth (Williams et al., 2020). It is considered that a consequence of cooperating with preventive measures and practicing the new normal, people have chosen to behave as socially expected, following the denial of behaviours or habits that have normally been a part of their lives and themselves. Psychological conflicts can emerge during the adoption of new lifestyles, and such conflicts can influence one’s core beliefs.

The subjective level of achievement in cooperation with preventive measures also significantly predicted the disruption of core beliefs, but not psychological distress. As the correlation coefficient between psychological burden and achievement was very low (r = 0.078), it seems that people who practiced preventive measures did not necessarily feel burdened. These findings suggest that during the pandemic, the practise of preventive measures in itself was not a harm for mental health. On the other hand, a previous study that examined the relationship between core belief disruption and mental health in Americans during the pandemic reported that those who practiced preventive measures that kept them away from society were less likely to have their core beliefs disturbed and had lower coronavirus anxiety (Milman et al., 2020a). The authors of this previous study speculated that the disruption of core beliefs may have been suppressed because choosing behaviours such as not going out, not travelling, and keeping a physical distance from others made the coronavirus threat appear controllable and predictable (Milman et al., 2020a). One of the important differences between this previous study and our study is that the lockdown was enforced in the US, but not in Japan. As Japanese law does not permit the enforcement of lockdown during an infectious disease epidemic, it is left to the people themselves to decide whether to practise any preventive measures. In other words, in the case of Japanese citizens, even if they themselves practise preventive measures, coronavirus threats would remain unpredictable and uncontrollable because they cannot control the behaviour of others. For this reason, cooperation in preventive measures was one of the factors that disturbed the core beliefs of the Japanese. In addition, although not statistically significant, the level of achievement of cooperation in preventive measures negatively predicted psychological distress. Since the practice of preventive measures is also associated with protecting others from the threat of coronavirus, it can be seen as altruistic behaviour. It has been found that altruistic behaviour amplifies positive emotions and attenuates negative emotions (Aknin et al., 2018; Brethel-Haurwitz et al., 2020). Therefore, it is speculated that practising preventive measures did not increase psychological distress.

The stressfulness of the outbreak and reduced income due to the pandemic also significantly predicted core belief disruption and psychological distress. A positive correlation between the stressfulness of an event and the level of re-examination of core beliefs has been demonstrated in previous studies (Cann et al., 2010; Lindstrom et al., 2013; Taku et al., 2015). Focusing on each CBI question item, the stressfulness of the pandemic significantly predicted the disruption of beliefs about other people (Q3. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my assumptions concerning why other people think and behave the way that they do.”, Q4. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my beliefs about my relationship with other people.”). This association may indicate that social aspects of lifestyle changes, such as decreases in face-to-face social interaction, peer pressure, and stigmatization, were the most stressful for people under the pandemic. On the other hand, reduced income due to the pandemic entered into the prediction model of the disruption of beliefs about self-worth (Q5. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my beliefs about my own abilities, strengths and weaknesses.”, Q6. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my beliefs about my expectations for my future.”, Q7. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my beliefs about the meaning of my life.”, Q9. “Because of the event, I seriously examined my beliefs about my own value or worth as a person.”). This finding is consistent with the findings of a qualitative study that showed that people who lost their income due to the pandemic lost motivation, meaning in life, and feelings of self-worth (Williams et al., 2020). A study with a large sample has also revealed that a reduction in household income is a significant risk factor for mental disorders (Sareen et al., 2011). Therefore, our findings support the proposition that people who have experienced a reduction in income due to the pandemic are at high risk for mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety.

A significant positive association between the level of disruption of core beliefs and psychological distress was demonstrated in the path analysis. This result is consistent with two prior studies that investigated the mechanism of mental illness caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Milman et al. (2020b) reported that core belief disruption due to the pandemic significantly explains the severity of depression, general anxiety, and coronavirus anxiety. Also, Oswald et al. (2021) revealed that mentally unwell youths showed greater disruption of core beliefs due to the pandemic than mentally healthy youths. On the other hand, many prior studies have suggested that disruption of core beliefs predicts post-traumatic growth after a traumatic event (Cann et al., 2010; Lindstrom et al., 2013; Danhauer et al., 2013; Wilson et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2015; Taku et al., 2015; Ramos et al., 2018; Eze et al., 2020). A possible interpretation of our finding is that the tendency for depression during the COVID-19 pandemic indicates a transition period for psychological growth in individuals. However, this expectation could be too optimistic in the present pandemic, which could take several years to completely subside (Kissler et al., 2020). Therefore, it is necessary to develop effective mental health care during and after the pandemic, bearing in mind the potential disruption of individuals’ core beliefs.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was conducted in a relatively monocultural country, characterized by a relatively low disease burden and a high degree of adherence to preventive measures. Although several studies have investigated core belief disruption due to the pandemic in other countries (Milman et al., 2020a, 2020b; Oswald et al., 2021; Dominick et al., 2021), further comparisons with other countries with different cultures and varying mortality rates from COVID-19 may be needed. Second, we had no data on the history of psychiatric diseases or treatment of our participants before the pandemic. It should therefore be noted that our analysis does not control for the possibility that psychological vulnerability may have influenced the extent of core belief disruption or psychological distress. Third, it is unclear what the participants found burdensome in cooperating with preventive measures. If a quantitative assessment of the details of these psychological burdens was realized, we may be able to more concretely understand the determinants of people’s psychological distress amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Fourth, the CBI is a measure of the extent to which core beliefs have been disrupted; it does not tell us what the individual’s core beliefs are, or how they have changed as a result of the event. There are well-known scales for assessing the nature of an individual’s core beliefs, such as the World Assumptions Scale (Janoff-Bulman, 1989; van Bruggen et al., 2018), but unfortunately, there is not yet a Japanese version. In order to clarify the universalness and cultural specificity of human psychology in the context of rapid social change like the present pandemic, it is necessary to develop a reliable scale.

In conclusion, this study revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the core beliefs among the general population of Japan at a relatively low level. It is clear that voluntary participation by the public with preventive measures is important to control the spread of infection; however, the psychological outcomes brought about by changes in one’s lifestyle should also be considered in the development of health policies.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available but can be made available to individuals approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University.

References

Akaike H (1998) Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Parzen E, Tanabe K, Kitagawa G (eds) Selected papers of Hirotugu Akaike. Springer New York, New York, pp. 199–213

Aknin LB, Van de Vondervoort JW, Hamlin JK (2018) Positive feelings reward and promote prosocial behavior. Curr Opin Psychol 20:55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.08.017

Brethel-Haurwitz KM, Stoianova M, Marsh AA (2020) Empathic emotion regulation in prosocial behaviour and altruism. Cogn Emot 34:1532–1548. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2020.1783517

Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG et al. (2010) The Core Beliefs Inventory: a brief measure of disruption in the assumptive world. Anxiety Stress Coping 23:19–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800802573013

Cénat JM, Blais-Rochette C, Kokou-Kpolou CK et al. (2021) Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 295:113599. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599

Danhauer SC, Russell GB, Tedeschi RG et al. (2013) A longitudinal investigation of posttraumatic growth in adult patients undergoing treatment for acute leukemia. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 20:13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-012-9304-5

Dominick W, Elam T, Fraus K, Taku K (2021) Nontraditional social support, core belief disruption, and posttraumatic growth during COVID-19. J Loss Trauma 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2021.1932968

Eze JE, Ifeagwazi CM, Chukwuorji JC (2020) Core beliefs challenge and posttraumatic growth: mediating role of rumination among internally displaced survivors of terror attacks. J Happiness Stud 21:659–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00105-x

Fukase Y, Ichikura K, Murase H, Tagaya H (2021) Depression, risk factors, and coping strategies in the context of social dislocations resulting from the second wave of COVID-19 in Japan. BMC Psychiatry 21:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03047-y

Furukawa TA, Kawakami N, Saitoh M et al. (2008) The performance of the Japanese version of the K6 and K10 in the World Mental Health Survey Japan. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 17:152–158. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.257

Idogawa M, Tange S, Nakase H, Tokino T (2020) Interactive web-based graphs of Coronavirus Disease 2019 cases and deaths per population by country. Clin Infect Dis 71:902–903. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciaa500

Janoff-Bulman R (1989) Assumptive worlds and the stress of traumatic events: applications of the schema construct. Soc Cogn 7:113–136. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.1989.7.2.113

Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ et al. (2002) Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med 32:959–976. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291702006074

Kikuchi H, Machida M, Nakamura I et al. (2020) Changes in psychological distress during the covid-19 pandemic in Japan: a longitudinal study. J Epidemiol 30:522–528. https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.JE20200271

Kikuchi H, Machida M, Nakamura I et al. (2021) Development of severe psychological distress among low-income individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic: longitudinal study. BJPsych Open 7:e50. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.5

Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E et al. (2020) Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science 368:860–868. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb5793

Krishnamoorthy Y, Nagarajan R, Saya GK, Menon V (2020) Prevalence of psychological morbidities among general population, healthcare workers and COVID-19 patients amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 293:113382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113382

Lindstrom CM, Cann A, Calhoun LG, Tedeschi RG (2013) The relationship of core belief challenge, rumination, disclosure, and sociocultural elements to posttraumatic growth. Psychol Trauma 5:50–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022030

Li Y, Scherer N, Felix L, Kuper H (2021) Prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 16:e0246454. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246454

Luo M, Guo L, Yu M et al. (2020) The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 291:113190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113190

Marvaldi M, Mallet J, Dubertret C et al. (2021) Anxiety, depression, trauma-related, and sleep disorders among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 126:252–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.024

Milman E, Lee SA, Neimeyer RA (2020a) Social isolation as a means of reducing dysfunctional coronavirus anxiety and increasing psychoneuroimmunity. Brain Behav Immun 87:138–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.007

Milman E, Lee SA, Neimeyer RA et al. (2020b) Modeling pandemic depression and anxiety: The mediational role of core beliefs and meaning making. J Affect Disord Rep 2:100023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100023

Morgan JK, Desmarais SL (2017) Associations between time since event and posttraumatic growth among military veterans. Mil Psychol 29:456–463. https://doi.org/10.1037/mil0000170

Nagasu M, Muto K, Yamamoto I (2021) Impacts of anxiety and socioeconomic factors on mental health in the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population in Japan: a web-based survey. PLoS ONE 16:e0247705. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0247705

Nochaiwong S, Ruengorn C, Thavorn K et al. (2021) Global prevalence of mental health issues among the general population during the coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 11:10173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89700-8

Noda Y (2020) Socioeconomical transformation and mental health impact by the COVID-19’s ultimate VUCA era: toward the New Normal, the New Japan, and the New World. Asian J Psychiatr 54:102262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102262

Oswald TK, Rumbold AR, Kedzior SGE et al (2021) Mental health of young Australians during the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the roles of employment precarity, screen time, and contact with nature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115630

Ramos C, Costa PA, Rudnicki T et al. (2018) The effectiveness of a group intervention to facilitate posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Psychooncology 27:258–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4501

Ramos C, Leal I (2013) Posttraumatic growth in the aftermath of trauma: A literature review about related factors and application contexts. Psychol Community Health 2:43–54. https://doi.org/10.5964/pch.v2i1.39

Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R et al. (2020) Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 16:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w

Sareen J, Afifi TO, McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG (2011) Relationship between household income and mental disorders: findings from a population-based longitudinal study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 68:419–427. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.15

Taku K, Cann A, Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG (2015) Core beliefs shaken by an earthquake correlate with posttraumatic growth. Psychol Trauma 7:563–569. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000054

van Bruggen V, Ten Klooster PM, van der Aa N et al. (2018) Structural validity of the World Assumption Scale. J Trauma Stress 31:816–825. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22348

World Health Organization (2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020.

Williams SN, Armitage CJ, Tampe T, Dienes K (2020) Public perceptions and experiences of social distancing and social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic: a UK-based focus group study. BMJ Open 10:e039334. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039334

Wilson B, Morris BA, Chambers S (2014) A structural equation model of posttraumatic growth after prostate cancer. Psychooncology 23:1212–1219. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3546

Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F et al. (2020) Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: a systematic review. J Affect Disord 277:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

Yamaguchi K, Takebayashi Y, Miyamae M et al. (2020) Role of focusing on the positive side during COVID-19 outbreak: mental health perspective from positive psychology. Psychol Trauma 12:S49–S50. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000807

Yoshioka T, Okubo R, Tabuchi T et al. (2021) Factors associated with serious psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: a nationwide cross-sectional internet-based study. BMJ Open 11:e051115. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051115

Zandifar A, Badrfam R (2020) Iranian mental health during the COVID-19 epidemic. Asian J Psychiatr 51:101990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101990

Zhang H, Li W, Li H et al. (2021) Prevalence and dynamic features of psychological issues among Chinese healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and cumulative meta-analysis. Gen Psychiatr 34:e100344. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100344

Zhou X, Wu X, Fu F, An Y (2015) Core belief challenge and rumination as predictors of PTSD and PTG among adolescent survivors of the Wenchuan earthquake. Psychol Trauma 7:391–397. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000031

Zhu X, Neupert SD (2021) Core beliefs disruption in the context of an slection: implications for subjective well-being. Psychol Rep https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211021347

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (1991). Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Tohoku University (Approved No. 2020-1-575).

Informed consent

The purpose of this study was explained in a document that was displayed on a web page. Informed consent was obtained from participants through the submission of their response to the questionnaire.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Matsudaira, I., Takano, Y., Yamaguchi, R. et al. Core belief disruption amid the COVID-19 pandemic in Japanese adults. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 292 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00976-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00976-7