Abstract

This study explored perceptions, experiences and opportunities for the occupational safety and health professional (OSHP) as a result of COVID-19. Using qualitative methods, interviews took place with OSHPs in two organisations to understand how their role developed during the pandemic. Additionally, seven focus groups were organised and met virtually, using the Zoom platform, each addressing a different topic identified by the researchers. Participants (n = 45) from 10 different countries were distributed among the focus groups. Topics were separated into four themes: impact on the workplace; the psychosocial dynamic; medical and health issues and occupational safety and health (OSH) issues. Results were subsequently divided into seven action categories and compared with the findings from the organisational interviews. Comparison pointed to an expanded role for the OSHP including business continuity, resilience and wellbeing in addition to assessing and controlling risks emerging during the pandemic. There is also the need for a means to adequately disseminate trustworthy information. Results indicated that there was no single ‘average’ role of the OSHP, demonstrating essential contributions as a member of the management team. Results also stressed that the pandemic carried three health-related co-morbidities, stress, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and burnout. Directions for future research included: the education of the OSHP to support a move away from compliance towards risk management; determining how mental health issues in organisations should be managed; expanded roles for OSHPs within business; and implications for professional bodies, membership institutions and academia in supporting the above-mentioned emerging roles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The impact of COVID-19 has been considerable in the cost to human lives, human health and economic stability. Since its origins in late 2019, the epidemic caused by the virus SARS-CoV-2 and the disease COVID-19, escalated to a pandemic by the World Health Organisation (WHO) (2020), and has had a dramatic impact. Most nations of the world lacked the preparedness to initially and continually manage the pandemic. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) (2020a) stressed the need for member States to work rapidly for the on-going provision of adequate information, protection and the continuation of essential services in managing the situation. Under pillar 3, it called for the strengthening of OSH measures and the promotion of public health measures at work.

COVID-19 has raised the profile of the occupational safety and health professional (OSHP); continually contributing to the risk assessment process (which includes evaluating and putting into place control measure to eliminate or mitigate safety, health or environmentally associated risks) (Bubbico, 2011). Businesses, organisations and institutions have called upon OSHPs to work with other professions to review and implement COVID-19- related incident plans, resilience plans (Cabinet Office UK, 2013), home working arrangements and back to work schemes. However, as companies prioritise these areas of concerns, OSHPs need to continually ensure that, non-COVID-19-relalted operational safety, health and fire safety issues are not ignored.

There are many essential workers. A recently published article describes how emergency health care workers are facing unique work demands “… in addressing treatment of patients with the virus including, the potential lack of personal protective equipment (PPE), lack of critical equipment for treating serious cases of COVID-19 … (Britt, 2020)”. The OSHP, as an essential professional in managing OSH, is often in a position of providing advice to the employer and organising mechanisms to provide employee assistance for psychosocial problems and related issues (Health and Safety Authority Ireland, 2020; Brun and Loiselle, 2002; Dollard and Neser, 2013; Toderi and Balducci, 2015).

Despite being a Chartered Profession there is considerable variance with roles regulated in places such as Hong Kong (Factories and industrial undertakings regulations, 1986) and Singapore (Workplace Health and Safety Act, 2007) with continual debate elsewhere in the world (Wright et al., 2019) as to how this links in with education. In Switzerland, for example, there are four different professional profiles of OSH specialists including occupational doctors, occupational hygienists, safety engineers and safety managers, each with different requirements (Government of Switzerland, 2020). Hale and Booth (2019) identified that this variance may be due to the multitude of roles individual businesses need requiring different provisions resulting in the generalist advisory role now enshrined in their training yet not required by law. Wright et al. (2019) identified the importance of ‘influencing skills’, based either on innate or trainable personal qualities and the ability to argue and communicate, on social skills and positions of class and social standing, or on knowledge and competence”.

ERM (2018) identified that management commitment was a concern with too few engaging (48% of frontline leaders, 60% of mid-level managers and 70% of senior leaders), and too few spending too little time in the workplace (30% of frontline leaders, 52% of mid-level leaders and 36% felt leaders at all levels were effective at hazard recognition/engaging effectively as coaches on the frontline). ERM (2020) identified issues with contracting out mental health in the workplace and improvement not keeping pace with changing expectations with leaders needing to step up and gain new skills. The competencies required vary from process safety, industrial hygiene and broader risk management skills to soft skills such as communication, diagnosis and analytical skills, as well as the application of technology. ERM (2020) identified technical knowledge as a vital skill but did not expand on what this means. A skillset is suggested, from competent operator to management consultant, all within the same person and a person employed to fill up and cover gaps in management (Hale and Booth, 2019; ERM, 2018, ERM, 2020). Mental health at work is a complex topic that includes workplace factors, the home/work interface as well as individual biological/psychosocial factors that the employer is unlikely to be aware of (Harvey et al., 2014).

Four phases of a pandemic are described by WHO Europe (2020a) including: interpandemic; alert; pandemic; and transition. The transition towards recovery requires an understanding of how people behave considering the complex and changing psychosocial, societal and cultural factors. WHO Europe (2020b) suggests that, “risk perceptions influence individuals’ judgements and evaluations of threats, and can adversely affect public compliance with and response to information communicated by authorities.” This is supported by a report issued by the International Council for Science (2008) that states:

Risk depends not only on hazards but also on exposure and vulnerability to these hazards, making risk an inherently interdisciplinary issue. In order to reduce risk, there needs to be integrated risk analysis, including consideration of relevant human behaviour, its motivations, constraints and consequences, and decision-making processes in face of risks.

The world of work is changing with the World Economic Forum (2020) not mentioning OSH as a specialism and linking it as a skill as “Quality Control and Safety Awareness”. It identifies Project management and risk management specialists as an area for increasing demand yet identifies decreasing demand for human resources (HR) and training and development specialists (p. 30). Amongst the top skills for 2025 are “critical thinking and analysis, resilience, stress tolerance, and flexibility” (p. 36) somewhat distanced from a compliance-based profession.

The aim of this ‘task and finish’ study (University of Aberdeen, 2020) was to explore the extent of how OSHPs have had to adjust to the pandemic and how this adjustment can be consolidated in the profession (Madsen et al., 2019). This would be done through examining case studies from practice and obtaining perspectives from OSH leaders and practitioners from different parts of the world through focus groups. This will enable opportunities identified for the OSHP supporting work in a broader risk-based world of work with additional networks and competencies as a result of COVID-19 and beyond.

Methods

The scope of the study included the authors and leading volunteers from the Institution of Occupational Safe and Health (IOSH) (Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Network UK, 2019) identifying examples of cross disciplinary working, leadership and engagement with other professions and comparing with relationships identified in the literature. As a ‘task and finish’ study requiring fast capture of data it was agreed participants would be approached using sampling by convenience (Garrido et al., 2015; Etikan et al., 2016; Thomas et al., 2019).

The Zoom platform (Archibald et al., 2019) rather than face-to-face interviews and focus groups was used. This protected the participants from exposure to the virus. Researchers also point out that point out that virtual internet-based mechanisms provided an opportunity to reach and include geographically dispersed participants (Matthews et al., 2018). Due the UK Data Protection Act (Government of the UK, 2021) it was agreed not to record the interviews but to manually transcribe the outcome of the Zoom sessions.

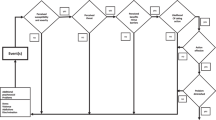

Figure 1 summarises how the methods used generated data and how the outputs were compared and analysed with the literature to identify both barriers and opportunities going forward. Information from both exercises was transcribed with the key findings summarised under broad categories and themes that evolved from the process.

With limited opportunities during the pandemic for OSHPs to meet and discuss issues, on-line focus groups were identified as a means to gather information. The use of qualitative research provides an opportunity to explore social responses (Teti et al., 2020). Focus groups were identified as a means of capturing participant’s experiences, opinions and perspectives (Marques et al., 2020; Kitzinger, 1995). Focus groups when conducted virtually can be conducted synchronously, asynchronously, or using a combination of both (Tates et al., 2009). The seven focus groups described in this paper were conducted synchronously with all participants in a group on line at the same time.

Seven topics (one for each focus group), were addressed by the study, each topic was examined regarding its relevance to the OSH profession, its impact based on COVID-19, and opportunities that the topic may present for the profession in the future.

The study carried out a brainstorming exercise (Osborn, 1953) on 8 August 2020 to identify the key topics that had been prevalent during the first 4 months of the pandemic. This identified seven topics and it was agreed to discuss each of these at a separate focus group to achieve adequate depth of information.

The first topic examined ‘emerging arrangements and challenges in the workplace’. At the time social distancing was not universally introduced, a number of workers were not provided appropriate PPE, and there was a lack of knowledge as to whether COVID-19 related risk assessments were carried out in the workplace (Trade Union Congress, 2020). The pandemic also changed the nature of the working environment as non-essential workers found themselves working from home, redundant or furloughed (Parington, 2020) which was at times complicated by the presence of and pressures from family (Kniffen et al., 2021).

The second was “complacency and resistance to protective measures”. Erhabor et al. (2021) examined strategies in West Africa to limit the spread of COVID-19 and stressed the need for the public to avoid complacency and take the necessary precautions to protect themselves and others. According to WHO Europe (2020c), during the pandemic people, over time, may change their disease-related behaviour based on the cultural, social and legislative environment. WHO Europe (2020d) defines ‘pandemic fatigue’ as a “natural and expected reaction to sustained and unresolved adversity in people’s lives. It expresses itself as demotivation to engage in protective behaviours and to seek out information, as well as in feelings of complacency, alienation and hopelessness”. Another dynamic that potentially encourages complacency is Groupthink as initially described by Janis (1972). Forsyth (2020) suggests that groups that resist certain health interventions such as vaccination and quarantine may be influenced by Groupthink which he defines as a deterioration of judgement and rationality that can occur in highly adhesive groups.

The third topic was ‘dynamics related to different generations of workers and vulnerability’. Fear and concern for health has created a certain gap between the lower-risk younger generation and more vulnerable older adults. Ageism includes prejudicial attitudes and practices that may discriminate (Butler, 1980). Ayalon et al. (2021) suggest that:

… younger people tend to view themselves as immune to the virus and, thus, engage in risk behaviours with consequences that ultimately will need to be addressed by an already stressed health care system. … Rather than pitting generations against each other, we should facilitate intergenerational exchange and solidarity.

Adequate, well sourced communications should always be used to avoid negative rhetoric and speculation fostering perceptions that can lead to senseless risk decisions (Swain, 2012).

Yamey and Walensky (2020) suggest that students can carry the disease, potentially infecting faculty, staff and other members of the community that may be in a higher risk group. Many universities have worked pro-actively in reducing this risk with enhanced communications and processes agreed between students and staff (Middlesex University, 2020). Walke et al. (2020) stated:

Although the risk of severe health outcomes from COVID-19 in young adults without underlying health conditions is relatively low, faculty, university staff, and close contacts of college students at home and in the community might be at a considerably higher risk for severe illness and death if they were to become infected.

The fourth topic considered was Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). The term PTSD surfaced in the 1970s after the war in Vietnam (Crocq and Crocq, 2020). Although noted by Bisson (2007) in 1980 PTSD was formally recognised as a psychiatric disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (3rd edition) (American Psychiatric Association, 1980), there is still controversy as to whether the diagnosis of PTSD requires the patient to have actually experienced the trauma directly (North et al., 2020). It is clear from the literature, that there are certain exposures that commonly lead to PTSD including traumatic events (Williams, 2002). Horton (2020) states that, “The focus of the political debate about coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) has so far been almost exclusively about the public health dimensions of this pandemic. But at the bedside there is another story, one that has so far been largely hidden—a story of terrible suffering, distress, and utter bewilderment.” Xiang et al. (2020) conclude an article in the Lancet with the statement:

In any biological disaster, themes of fear, uncertainty, and stigmatisation are common and may act as barriers to appropriate medical and mental health interventions. Based on experience from past serious novel pneumonia outbreaks globally and the psychosocial impact of viral epidemics, the development and implementation of mental health assessment, support, treatment, and services are crucial and pressing goals for the health response to the 2019-nCoV outbreak.

PTSD was frequently recognised as a disorder affecting military personnel and emergency workers, it is now also seen in the workplace as a result of occupational accidents (McFarlane and Bryant, 2007). Research points to the need to focus on the importance of understanding the symptoms of PTSD among health care workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic (Carmassi et al., 2020). Citing Wang et al. (2020) and Peeri et al. (2020) about the history of COVID-19, they go on to discuss the situations the health care worker faces that increase the risk of PTSD including the risk of being infected by COVID-19; being a source of infection; working with large numbers of critically ill patients; the unpredictable course of COVID-19; as well as high mortality rates and lack of effective treatment and treatment guidelines (Carmassi et al., 2020).

The fifth topic considered was the ‘potential of reduced work forces and implications for OSH’. In a number of countries telework has become the norm for non-essential services. For many workers, the work and non-work roles have become interlinked (Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir, 2020). As schools closed, many preschool children as well as children, adolescents, and young adults in all levels of education were at home creating a form of family conflict where different family members had to assume different roles at different times. A number of these roles added to additional burdens of daily life. While the parent(s) were teleworking, for example, the youngest may have needed care and attention, while older children may have needed help with their lessons. Additionally, many of these workers may have never worked from home before and needed to learn how to effectively telework. Workers found themselves, “working from their kitchen table, living room sofa, or other makeshift office spaces (Allen, 2020).” It was therefore highly stressful to set and maintain boundaries between work and family demands (Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir, 2020).

With many front-line emergency health care workers having long working hours with increased contact with patients and their risk of infection there is a cumulating effect causing increased levels of anxiety, depression and stress, suggesting urgent need to manage their mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic (Lai et al., 2019). Dupey et al. (2020) suggest the reduction of the workforce due to COVID-19 and a lack of availability of worker’s due to the pandemic could lead to situations that compromises OSH. They suggest when it is necessary to come to work that the four points in Table 1 should be adopted.

The sixth proposed topic questions ‘whether the world of work is losing sight of basic safety and health issues’. Many workers are considered essential workers whose safety and health needs have to be addressed including provisions such as the up-to-date qualified information, emergency procedures to follow, hygiene, cleaning, physical distancing, and PPE (ILO, 2020b). While the WHO has identified seven pandemic-related roles of the safety and health professional (Ivanov, 2020) there are many non-essential workers that continue to work their normal workplaces or by teleworking from home. The day-to-day, non-COVID-related OSH measures need to be sustained for all workers during the pandemic (Elliswhittam, 2021). These include measures that address: fire safety; hazardous material including chemical and biological materials, vehicle safety, materials handling, working in confined space, hot work, machine safety, emergency procedures and first aid, incident investigation, ergonomics, procedures for start-up, shut down and maintenance, critical and routine training, safety communications and health communications. All workers need to be afforded basic OSH protection with the view to avoid injuries and illness related to their work. The ILO’s Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) outlines a number of the above-mentioned safety and health requirements that should not only be in place but continue to be reinforced. Article 18 states that, Employers shall be required to provide, where necessary, for measures to deal with emergencies and accidents, including adequate first-aid arrangements (ILO, 1981).

THE (UK) Health and Safety Executive (HSE) (2021) states that, “… there is a legal duty to assess the risks to health and safety of your employees … to which they are exposed while they are at work.” The ILO (2014) outlines a five-step process that not only determines the risk but proposes and test control measures to either eliminate or mitigate the risk.

When controlling the risk (ILO, 2014), the use of the ‘hierarchy of controls’ is an important element (Lyon and Popov, 2019; Manuele, 2014). Today the hierarchy of controls is frequently used to determine which control measure (in priority) should be activated. A European Council Directive (1989) spells out a hierarchy of control measures as part of the general principles of prevention. According to the (US) National Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (2015) the five elements of the hierarchy of controls, in order of effectiveness are: Elimination; Substitution; Engineering Controls; Administrative Controls and Personal Protective Equipment.

The seventh topic proposed was to ‘explore whether OSHPs understand burnout and whether it is associated with COVID-19’. Burnout is not clearly defined and there is a lack of consensus on the elements to make a diagnosis, however, burnout had become the focus of concern and numerous studies (Heinemann and Heinemann, 2017). Freudenberger (1974) suggests that burn-out means “to fail, wear out or become exhausted by making excessive demands on energy, strength, or resources.” He described a condition he observed in himself and some of his colleagues.

The WHO (2019) defines Burnout as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed. It is characterised by three dimensions:

-

feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion;

-

increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job; and

-

reduced professional efficacy.

Burn-out refers specifically to phenomena in the occupational context.

Morera et al. (2020) suggest four phases of Burnout as Engagement, Strained, Cynicism and Burnout. Restauri and Sheridan (2020) go on to suggest interventions that can prevent Burnout, acute stress disorder and PTSD including flexible working, awareness and support, top down communication and bottom up engagement.

Focus groups

The study agreed that facilitation of the focus groups would start in August 2020. The methodology followed the 14-step pattern described below:

-

1.

An objective was set and a list of six topics was developed (the seventh topic surfaced during the focus groups).

-

2.

A draft was prepared including the initial question and a descriptive paragraph that gave background.

-

3.

As the primary author was going to assume the role as moderator, a co-moderator was proposed and agreed upon for each focus groups.

-

4.

The draft question and descriptor were reviewed by the moderator and co-moderator and finalised.

-

5.

Beside the moderator and co-moderator 8–10 participants were selected for each group with a profile of who should be included in the focus groups was agreed upon; and a question to stimulate thoughts was proposed.

-

6.

The moderator contacted each potential participant by telephone or email to determine their interest and availability.

-

7.

Once confirmed the moderator sent out to the participants the question and descriptor for their group.

-

8.

The moderator and co-moderator met to discuss the rollout of the session, potential problems, and questions that should prepared and asked if the discussion stalled.

-

9.

The meeting was scheduled based on the availability of the moderator, co-moderator and the majority of the confirmed participants. The participants were informed by email.

-

10.

On the day of the focus group meeting a reminder was sent to each participant.

-

11.

The moderator initiated the meeting explaining the rollout and procedures.

-

12.

The moderator asked the co-moderator and each of the participants to briefly introduce themselves and provide their view of the current situation vis-à-vis the current topic. In a second round of all participants the moderator asked each participant to present their views on the way forward. This was followed by a general discussion and a summary by the moderator.

-

13.

The moderator and co-moderator took notes.

-

14.

The notes were compared by the moderator and co-moderator and synthesised when necessary.

The focus groups met between 28 August and 7 September 2021. The seven topics and the number of participants per focus group are listed in Table 2.

Participants

Participants were all established OSHPs who were senior volunteer members of IOSH. The study selected participants from three cohorts, as outlined in Table 3, some of whom had fulfilled one or more roles. Additional participant demographics can be found in Fig. S1, Supplementary information Table S1.

Each of the sessions were invitational. Forty-five participants participated in the seven sessions with the co-authors and three additional participants participating in more than one session.

Using the Occupational Coding Tool Classification of the UK Office of National Statistics (2021) as a basis, participants assigned themselves into one of the following categories as outlined in Table 4.

As previously indicated, the moderator and co-moderator compared and synthesised notes at the end of the session, identifying and confirming the key statements and messages from each group. Outputs from each group were compared indicating many outputs were cross cutting resulting in:

-

The breakdown of statements into organisational cross cutting themes grouped around whether they were strategic, tactical or operational (Bertoni, 2017) and, the identification of challenges around competencies, research and legislation.

-

Use of software (Bhargava and D’Ignazio, 2021) to identify key words and phrases identified in the transcript (1–3) words to pick up relevant phrases and words excluding irrelevant prepositions, verbs, etc.

Case studies

The case studies examined two different organisations. Structured interviews were carried out with OSHP post holders who had expanded corporate roles. During the pandemic both operated in a more flexible matrix management environment and had others reporting to them. Each interview was carried out by telephone or zoom by a different researcher who was familiar with the operations and known to the organisation’s management.

-

The first case study was a global company based in Geneva, Switzerland. The professional interviewed had a previous degree qualified career and was in a senior HR role.

-

The second case study was a UK Local Authority; the professional interviewed had a previous military career and was also trained and competent in business continuity (BC) and emergency management.

The interviews were designed to be open conversations and establish what the person had done. Notes were taken by the interviewer. After the interview and within 24 h the notes were collated and sent to the interviewee to check for accuracy of content and for any errors to be corrected.

The case studies focused on the background, the actions in company, key impacts around corporate social responsibility (CSR) and resilience outcomes.

Results and findings

Results were collated, as previously stated, with outcomes from the focus groups broken down into: Strategic-Direction of Profession; Strategic Organisational Influence; Processes; Tactical Skills; Operational Understanding; Areas for Research and issues around Professional Competencies; Legislation as well as activities that could be incorporated into roles for other professions or roles that the participants identified as relevant.

Focus Group results were compared with information from the case studies to not only corroborate experiences from the focus group but also to identify additional relationships, engagements and influence. The outputs indicate that those at all levels within their organisation are working outside the traditionally envisaged role of an OSHP.

The focus groups identified a number of opportunities and challenges identified by responders (see Fig. S1 and Supplementary information Table S2). At least four groups identified opportunities and challenges around the profession itself as reflected by several respondents who stated that there needed to be a, “reset where we place our efforts … especially with leaders of business. Respondents asked, “Is there a change in the occupational safety and health paradigm?” and how this fit into the broader world of business and that experiences and contribution to business area catalyst to change. It was raised during the focus groups by participants that it is essential to, “Strengthen the role and importance of the occupational safety and health profession locally and globally.” A number of respondents indicated broader risk management roles adding value to business, and to “Encourage the movement from compliance management to risk management.” Two respondents identified the importance of engagement with HR and others at strategic level when developing sustainable absence and flexible working policies. They suggested that, “…we need to encourage dialogue at an HR level, between a company’s leadership and line managers so everyone is dealing with stress and burnout related issues in a strategic and down-to-earth way”. Table 7 raises issues around the direction of the profession indicating that established OSHPs in organisations can offer business far more in terms of broader business risk management including HR and BC (supported by the two case studies). This suggests that professional OSH institutions need to broaden their own competencies and create a route for those who operate and progress their careers through corporate routes. Here OSH management roles often reduce as they gain responsibilities for other professional roles as part of a corporate career development. In effect this suggests that this will create opportunities for individuals to move into broader roles of strategic influence whilst retaining their OSH knowledge.

With seven respondents mentioning mental health and stress interchangeability and another mentioning mental health, indicating a perceived opportunity suggesting competence in carrying out mental health risk assessments and mental health first aid, participants recognised that, “The OSHP needs to get involved in mental health, ensuring support mechanisms are in place and facilitating the role of mental health first aiders.” One participant queried, “How far does the OSHP go? What is our role and how is it different than the mental health first aider?” In clarifying the role of the OSHP, one participant suggested that the OSHP are “Facilitators who look after the doers.” It was stated in one focus group that, “We need to define the scope of the question and define what we mean by ‘addressing’ PTSD.” Another participant stated that, “mental health risks are not being assessed well.”

There were comments stressing a need for greater regulation around mental health at work following Covid-19 although it was uncertain if this was UK or something more global.

A respondent recognised that “This (COVID-19) is a massive opportunity for the OSHP.” Some respondents indicated that their role was to assist the organisation in practically interpreting and implementing government advice noting that “It is essential that there are solid and consistent policies regarding COVID-19 sickness from work and stay-at-home policies”. This led to one respondent suggesting that “OSHPs need to learn more about the virus from credible sources; its biology, how its transmitted and its associated risks.” This developed into a suggestion that “OSHPs understand mechanisms of transmission and associated risks” of viruses such as COVID-19.

Some respondents indicated that, “…there were competency issues regarding management and their decision making. Some corporate leaders are returning to a situation where OSH decisions are being made with no underlying risk assessment possibly associated with businesses having to cut costs to survive.” A respondent suggested that, “There is currently a move within companies to save money which translates in some situations to a reduction in OSH services.” It was also pointed out that “Many sites have shut down except for a skeleton crew ignoring security and maintenance checks—In process safety issues relating to lock down and start-up.” Arising out of this, it may be important for operational management to better understand OSH. A participant reflected that, “Standard operating procedures now need to be replaced with dynamic operating procedures due to the rapidly changing risks.”

Operationally a number of issues were identified around flexible working. A respondent shared that, “People cannot afford to stay off sick. They may come to work infected so they can maintain their jobs.” and presenteeism/ill health management were raised within the focus groups. Another operational issue that surfaced during the pandemic was prejudicial attitudes between different generations including the vulnerability of younger workers and ageism. Responding to this concern a respondent reflected, “There is an important need for a targeted messaging campaign. There should be messages for both the old and the young”.

It was suggested by a respondent that, “Many organisations are lacking BC plans and have collapsed leading to unemployment.” Some respondents identified the opportunities for their involvement in the development and implementation of BC plans. It was stated that, as a learning point from the pandemic, “We must build resilience into the workplace by having an up-to-date incident plan that can be adapted as the situation changes.”

Focus groups also addressed the need to improve legislation around mental health at work. A respondent stated the, “Practical means need to be urgently found and implemented to identify positive behaviours to avoid stress early.” There are also findings around how organisations manage health and more specifically concerning support of staff and the provision of Employee Assistance Programmes (EAP)s. Employee health is also something where further research is needed focusing on the challenges and relationships between, stress, PTSD and burnout as well as investigation of the relationships between the antecedents of work-related stress and mental health conditions. Specific to the pandemic the study supports continued research into the issues due to the physical and mental effects of COVID-19.

There are also findings around how organisations manage health with findings around support of staff and the provision of EAPs. Employee health is also something where further research is needed around the challenges and relationships between, Stress, PTSD and burnout as well as investigation of the relationships between the antecedents of work-related stress and mental health conditions.

Specific to the pandemic the study supports continued research into the issues due to the physical and mental effects of COVID-19.

The ability to communicate at all levels has been identified with professionals having key roles in supporting the broader organisational response; one respondent stated, “We must build resilience into the workplace by having an up-to-date incident plan that can be adapted as the situation changes.” This needs to be accompanied by broader understandings of risk and the suggestion that post holders have strong transferrable skills that employers often are reluctant to identify.

Table 5 summarises the results of the focus groups from the perspective of professional direction. Table 6 summarises the results from a perspective of research competencies and other findings.

Figure S1, Supplementary information, Table S3 summarises the outputs from the word frequency count (Bhargava and D’Ignazio, 2021). The predominant word was Health (187) occurrences followed by Safety (79), COVID (94), and Risk (78), which was not surprising when considering the composition of the focus groups. It did identify words such as management, business and mental health, however this did not produce any trends that could be further explored.

It was also found that some regulatory regimes need to be reviewed and to consider appropriate employment standards for mental/physiological health in the workplace.

The case studies identified two particular trends, firstly significantly increased work activity in safety and health activities much of which was health and hygiene related. Secondly, using broader risk management tools to diversify into other areas of risk. The case studies are summarised in Table 7 with full text in Fig. S1, Supplementary information, Table S4.

This is consistent and supports some of the findings from the focus groups. Both have previous experiences and roles that have allowed their organisations to fully utilise their skillset and meet the varying demands of the business. This is something that those operating as external OSH consultants may not see—or have need to see—suggesting that there is a difference in professional practice.

Specifically

Case study 1 identified that the OSHP function (combined with environmental management) works as a peer profession to the HR management team. The Environment, Safety and Health (EHS) team, in addition to their day job, was engaged in adapting and implementing infection-related risk assessment to the current situation. Providing considerable support in transitioning from site work to working from home and helping local EHS (site) professionals manage the response to the pandemic. Their work was well above and beyond their day job requiring considerable additional work (to the limit of their capacities). Other key activities included the creation of comprehensive guidance created globally for implementation locally. This included risk management for working on sites, priority to protect production and laboratory workers as well as those working at home. This led to the creation of BC teams which included OSHPs. tracking of cases was established with results reported by site, numbers in quarantine and employee fatalities; global procurement planning was made for pandemic-related PPE; and site support networks were established and led by the heads of corporate compliance and EHS, including best practice calls.

Case study 2 identified that OSHP are functioning as general risk managers in a broader more corporate role. Emergency Response and BC. These roles involve both understanding business risk, being able to advise business and network across boundaries and professions. Key skill sets demonstrated includes risk profiling, emergency management, communication and liaison in a fast-moving government led structure. The post holder is also personally responsible for the management of the Local Authority test centre.

Our findings suggest that the pandemic has created a situation that has expanded the role of the OSHP with their competencies utilised during the pandemic to support the organisation and engage with management on issues at different levels. The findings of both the focus groups and the case studies indicate that further change in the value of the OSH profession is needed with one respondent going so far as to suggest that professional and membership institutions “… should use the current situation as a springboard to not only strengthen the profession but also to strengthen the recognition of the profession as an essential service.” This creates both uncertainty as well as opportunity. Another respondent reflected that, “The future will now translate into a new way of doing business which is yet to be defined with some OSHPs embracing change”.

Discussion

Our findings support that the use of online focus groups conducted synchronously (Tates et al., 2009) is a valid way of gathering qualitative data (University of Aberdeen, 2020; Teti et al., 2020; Marques et al., 2020; Kitzinger, 1995) and together with the case study represent a valid method of undertaking a snapshot investigation.

The study identified a number of key themes that build upon the existing literature and suggests that there are those who work within as OSHPs (mainly those in the focus groups) but others who are professionals whose roles include OSH activity (the case studies). The study suggests seven focus group proposals that are related to the strategic direction of the profession (Wright et al., 2019) as well as two related to organisational influence as well as opportunity to participate at strategic, tactical and operational level, depending on the role and individual competencies.

Covid-19 has affected everyone and the role of the OSHP. At a professional level, there is a need to strengthen the importance of the OSH profession (Madsen et al., 2019). Our findings point to encouraging the movement from compliance management to risk management. Specifically, within the role our findings confirm that the role of the OSHP (Health and Safety Authority Ireland, 2020; Brun and Loiselle, 2002; Dollard and Neser, 2013; Madsen et al., 2019) is moving beyond that of an adviser and is most important in managing COVID-19 risks at work. The focus groups confirmed that human behaviour (the psychosocial dynamic) relating to the pandemic (WHO Europe, 2020a; WHO Europe, 2020b) can lead to outcomes that can place individuals and groups at risk.

Lack of top line engagement in the workplace including a lack of supervisor visibility—in-house OSHPs are in a position to influence and contribute across the whole organisation and engage with the senior management by providing opportunity for the OSHP to re-examine with leaders of business where efforts need to be placed in providing technical services. This builds on the Government of Switzerland (2020) and Hale and Booth (2019) which supports the argument that many employers expect OSHPs to have ‘technical and operational’ skills believing that OSHPs can provide cover for lack of management and supervisory activity; in effect acting as surrogate supervisors and managers (Harvey et al., 2014).

The study has identified a variation with roles sometimes linked to general advisory roles (Health and Safety Authority of Ireland, 2021; Brun and Loiselle, 2002) confirming an emerging belief that there is no single ‘average’ role for OSHPs. The challenges for businesses as evidenced in the case studies provided opportunity for OSHPs working in a corporate environment where the role meant direct ‘doing’ and managing (ERM 2018, 2020).

This suggests broader opportunity in building resilience within the business for those who develop broader risk management operationally, expanding the notion that the OSHP roles are normally engaged in a capacity to prevent death, injury and illness due to incidents related to work (ERM, 2020; WEF, 2020). Their work should be moving the paradigm from compliance management to risk management. Our findings strongly suggest that a fundamental aspect is the management of risks. We find that the five-step risk assessment process is an effective tool to identify, evaluate and determine the appropriate control measures for OSH risks. The OSHP needs to not only identify gaps in relating to the pandemic in its acute and recovery phases (WHO Europe, 2020a, 2020b), and continue to ensure basic safety and health control measures are being observed but also work with business leaders to capture what’s left behind after COVID and explore how OSH adds value to the business (ILO, 2020a; Bubbico, 2011). An essential part of that is to ensure, for example, that there are robust and consistent policies (Health and Safety Authority Ireland, 2020) regarding both sickness from work and stay at home policies. Our research supported the literature on the pandemic-related roles of the OSHP (Walke et al., 2020) and confirmed the importance of continuing to provide basic and essential OSH measures (Allen, 2020; Lai et al., 2019; Dupey et al., 2020; ILO, 2020a, 2020b; Ivanov, 2020; Elliswhittam, 2021). There is also an essential need to encourage dialogue at a HR level, between a company’s leadership and line managers, for example, so everyone is dealing with stress and burnout related issues in a strategic and down-to-earth way (Bubbico, 2011; Britt, 2020; Hale and Booth, 2019). The role of supporting the development and continually updating incident plans and resilience plans are essential for this pandemic as well as future incidents (ERM, 2020).

OSHPS have a vital role in information management that includes communication from external agencies (WHO Europe, 2020b). There is also a critical role, during the pandemic to ensure information being generated and passed on to management and workers come from a credible source. There needs to be an implemented messaging strategy to ensure everyone is informed on a regular basis. With access to appropriate information OSHPs are able to apply professional practice to develop exercising the hierarchy of controls, correcting any misalignment caused by COVID-19. Control measures that prevent or mitigate the spread of the pandemic need to be continually reinforced. Therefore, a COVID-19-related risk assessment or an addition of COVID-19-related issues to a risk assessment tool is essential. A unique challenge for the OSHP is that a large portion of the workforce in both developed and developing countries is working from home. Our work shows that adequate, up-to-date guidance is lacking and, in some instances, there may be no social protection for these workers. There is also a challenge for OSHP to adequately assess associated risks.

The study also picks up concerns with OSHP providing help/support/advice on broader mental health issues as this is a specialised clinical area and may well mean working outside of the required competencies. Professions need to consider advice and guidance in this area. OSHPs have provided advice to employer on psychosocial issues (WHO Europe, 2020b; Xiang et al., 2020; McFarlane and Bryant, 2007). Many participants will not have a clinical qualification in mental health practice and care needs to be taken when OSHPs consider they are mental/psychological health experts (Wright et al., 2019; Government of Switzerland, 2020) when in fact their expertise may be limited to an understanding of tools such as the HSE Management Standards (Toderi and Balducci, 2015). This may be down to language with some countries having a different lexicology with different roles. With OSHP non-clinical professionals and with HR and organisational development (OD) professionals often responsible for ill health there are barriers of organisational silos—the case study at Givaudan identifies how the professions can work closer together. In some organisations responsibility for occupational health can be under the OSHP or HR and OD. This suggests that there is a need to develop professional training for OSHPs to obtain a clinical skillset to be competent to provide psychological advice but also to have the skillset to competently manage occupational health and EAP contracts (Government of Switzerland, 2020).

An essential tool to reduce the risk of stress and PTSD is to ensure that there is an adequate psychological and mental health risk assessment process including stress and burnout (North et al., 2020; Carmassi et al., 2020). While the OSHPs’ primary role will most likely not be as a direct provider of psychological and mental health first aid, they have key roles including ensuring: adequate training; that support mechanisms are in place; facilitation of the role of psychological and mental health first aiders; and the provision of briefings for managers and leaders to support and strengthen psychological and mental health at work (Dupey et al., 2020; ILO, 2020a, 2020b).

Finally, our study supports the notion of complacency and the WHO definition of Pandemic Fatigue (Erhabor et al., 2021; WHO Europe, 2020c, 2020d). The focus groups confirmed that ageism is an aspect of prejudicial attitudes leading to certain risk-related behaviours during the pandemic (Butler, 1980; Ayalon et al., 2021).

Our study supports the literature indicating that PTSD is an important potential outcome for not only health care workers (Xiang et al., 2020; Carmassi et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020; Peeri et al., 2020) but more broadly at the work (McFarlane and Bryant, 2007; Lai et al., 2019). It also supports the literature indicating that school closings and people working from home (Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir, 2020; Allen, 2020) has led to increased levels of stress at home (Hjálmsdóttir and Bjarnadóttir, 2020; Shaw et al., 2020). It also confirmed that the lack of availability of workers due to COVID-19 could compromise OSH. It supports the definition and dimensions of burnout (Heinemann and Heinemann, 2017; Freudenberger, 1974; WHO, 2019; Morera et al., 2020) and measure that can be used to prevent burnout, acute stress disorder and PTSD (Toderi and Balducci, 2015; Restauri and Sheridan, 2020). Notwithstanding, our findings indicate that while tactical issues to prevent or mitigate the spread of COVID-19 are being addressed, two co-morbidities are burnout and PTSD. There is a need, both internationally and nationally, to define the scope of evidence-based research with a view to develop a consensus on what is burnout and how to prevent it before it evolves into PTSD.

Our simplified model, below (see Fig. 2) brings together literature and our studies and identifies the vast diversity of activities OSHPs, especially in corporate roles. It identifies a three-dimensional aspect to competencies and experience each professional may have. In many cases roles encompass work that involves delivering to targets rather than providing advice and having a broader risk role resulting that the silo descriptor OSH does not reflect the value now being given. This does provide challenges for employers when being told they need OSH ‘advice and assistance’.

This suggests that membership of professional bodies based upon a sliding scale of membership grades as written may not differentiate sufficiently with regards differing skills and talents when wanting clarity. This has impact on both OSHPs and employers when looking to recruit and relying on an external benchmark.

The findings suggest many in an OSHP role feel they have more to offer suggesting that OSH is a transient role for many supporting the findings around ‘multi-careers’, supported by the changing demands of work (WEF, 2020).

There may be some unexpected biases in our study population that should be taken into consideration for future work. The members of the focus groups were all senior safety and health professionals from one institution (selection bias) and primarily UK based (geographic bias). Engagement was done only in the English language (linguistic bias). The age range of the respondents reflected the age range of senior occupational safety and health members of the Institution. There may also have been some bias in that most respondents were from economically developed counties where roles include intervening to manage ill health effects of work (Dollard and Neser, 2013).

Conclusions

The mix of participants led to rich discussions with consensus on positive qualitative results. There are many topics that should be considered by dedicated focus groups on the way the OSH profession should move forward as a result of COVID-19. We have only addressed seven but we have sparked interest for additional focus groups in the future. The focus group methodology, using a virtual platform such as Zoom allowed us to reach professionals world-wide that we would have had a difficult time gathering in face-to-face focus groups.

The study identified that Covid-19 created additional work within the scope of OSH and also those where OSH was a subset of a broader role with higher gravitas and subsequent remuneration operating outside of a traditional OSH role. By design or otherwise many have moved into organisational/business risk and resilience roles (covering business and people).

The study has identified both opportunities and challenges for OSHPs. Opportunities are that many have a skillset and desire to expand their risk-based roles with Covid-19 identifying how they can respond to change in the workplace.

Many have looked to fill the space of ‘mental health’ champions with a running definition of stress as a negative term the HSE used the term, “management standards” and themed their website to reflect an overarching language around mental health.

Those with emergency planning, BC and HR roles have other qualifications to support this broader diverse role, roles possibly more in line with UK legislation on ‘competent assistance’. OSHPs have demonstrated skillsets and value to business outside of the OSH descriptor and for many to revert to a confined OSH role would be a step back.

It appears that those working in a broader corporate risk or people-based qualification appear to have a more varied role with far greater gravitas with a better, broader understanding of the business. Such opportunity is not afforded to those engaged as specific OSH consultants with differences understood by professional institutions.

The challenges are associated with competency and professional issues. This includes possible competency issues with many perceived as mental/psychological health experts without clinical training, giving rise to the need to develop or signpost training to be professionally competent in this area. The varied world of work and fundamental challenges as to what employers want from correcting operational practice, providing assistance to roles with defined operational responsibilities is not compatible with the institutional competency and grading frameworks thus giving rise to challenges for employers filling a ‘job description’—a need often arising due to a lack of supervision.

Critically our findings have highlighted that those remaining in work have suffered both burnout and PTSD extending to a need for further research looking at how this has affected the relationships between the antecedents of work-related stress and mental health conditions. This extends to identifying a gap in management for businesses and why they need support that OSHPs are asked to fill, especially to promote workplace rehabilitation. Additionally, EAPs need to reflect the increase in PTSD and burnout.

Recommendations

Arising out of this study there are a number of recommendations. Firstly, for the added value reflecting the skillsets of experienced OSHP to move away from job roles and titles with term advice or adviser. Professional iinstitute’s need to advocate and promote broader risk and resilience skills and to take OSH out of, what is often a silo.

Our study suggests a need to raise the bar to enable the opportunity for broader business skills to be core to the professionals who want to develop a corporate risk-based career outside or partially including OSH. Professional memberships are designed to be linear from an entry grade to a top-level professional memebership grade. Our proposed model challenges the concept of the ‘average OSHP and suggests a three-dimensional aspect to competency and career progression, something not necessarily met by competency frameworks with businesses wanting less silo-based professionals.

Competency frameworks need to reflect and develop the three-dimensional model as highlighted in Fig. 2. This also opens up opportunities for the development of appropriate higher education programmes in broader risk and resilience areas for those in positions of owning the risk. The paper recommends that ongoing formal professional development for those wanting and claiming to become mental health professionals as well as roles often seen as HR roles

Finally, the study has identified three areas of research into the relationships between the antecedents of work-related stress and mental health conditions and the legacy of the effects of COVID-19 on the world of work.

Data availability

All data generated and/or analysed during this study are not publicly available for reasons of privacy. The data are therefore not available for public sharing, but can be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Allen TD (2020) The work family interface. In: Sinclair R, Allen T, Barber L et al M. Bergman, T. Britt, A. Butler, et al. (eds) Occupational health science in the time of COVID-19: now more than ever. Occup Health Sci 4:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-020-00064-3

Archibald MM, Ambagtsheer RC, Casey G (2019) Using zoom videoconferencing for qualitative data collection: perceptions and experiences of researchers and participants. Int J Qual 18:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919874596

American Psychiatric Association (1980) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 3rd edn, revised (DSM-III-R). Author, Washington.

Ayalon L, Chasteen A, Diehl M et al. (2021) Aging in times of the COVID-19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. J Gerontol B 76(2):e49–e52

Bertoni M (2017) Introducing sustainability in value models to support design decision making: a systematic review. Sustainability 9(6):994. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9060994

Bhargava R, D’Ignazio C (2021) Data basic IO https://databasic.io/en/wordcounter/. Accessed 16 Jun 2021

Bisson JI (2007) Post-traumatic stress disorder. Occup Med 57:399–403. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm069

Britt T (2020) Unique occupational health risks for emergency healthcare professionals. In: Sinclair R, Allen T, Barber L, Bergman M, Britt T, Butler A et al. (eds) Occupational health science in the time of COVID-19: now more than ever occupational health science. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41542-020-00064-3. Accessed 9 Feb 2021

Brun JP, Loiselle CD (2002) The Roles, functions and activities of safety practitioners: the current situation in Québec. Saf Sci 40:519–536

Bubbico R (2011) Efficient applications of risk analysis in the chemical industry and emergency response. JRACR 1(2):92–101. https://doi.org/10.2991/ijcis.2011.1.2.1

Butler RN (1980) Ageism: a forward. J Soc Issues 36(2):8–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1980.tb02018.x

Cabinet Office United Kingdom (2013) Preparation and planning for emergencies: responsibilities of responder agencies and others. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/preparation-and-planning-for-emergencies-responsibilities-of-responder-agencies-and-others. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

Cambridgeshire Fire and Rescue (2021) Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Local Resilience Forum (CPLRF). https://www.cambsfire.gov.uk/community-safety/be-prepared-for-an-emergency/cambridgeshire-and-peterborough-local-resilience-forum-cplrf/. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

Carmassi C, Foghi C, Dell’Oste V et al. (2020) PTSD symptoms in healthcare workers facing the three coronavirus outbreaks: what can we expect after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychiatr Res 292:113312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113312

Crocq MA, Crocq L (2020) From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2(1):47–55. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/macrocq

Dollard MF, Neser DY (2013) Worker health is good for the economy: union density and psychosocial safety climate as determinants of country differences in worker health and productivity in 31 European countries. Soc Sci Med 92:114–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.028

Dupey P, Singh G, Nagaraju G et al. (2020) Reduction of workforce due to impact of Covid-19 and occupational health and safety management at the workplace. IJOSH 10(2):92–99. https://doi.org/10.3126/ijosh.v10i2.33287

Elliswhittam (2021) Don’t Forget the Seven Basic Areas of Health and Safety. https://elliswhittam.com/blog/dont-forget-the-basics-7-areas-of-health-and-safety-covid-19/. Accessed 22 Mar 2021

Erhabor O, Erhabor T, Adidas TC et al. (2021) Zero tolerance for complacency by government of West African countries in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hum Antibodies 29:27–40. https://doi.org/10.3233/HAB-200413

ERM (2018) ERM Global Safety Survey 2018. https://www.erm.com/globalassets/documents/publications/2018/erm-2018-global-safety-survey-report.pdf. Accessed 19 Mar 2021

ERM 2020 (2020) ERM 2020 Global Health and Safety Survey: towards building a thriving workforce. https://www.erm.com/insights/2020-global-health-and-safety-survey-report/. Accessed 19 Mar 2021

Etikan I, Musa A, Alkassim RS (2016) Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am J Theor Appl Stat 5(1):1–4. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

European Council Directive (1989) 189/391/ECC in Article 6 general obligations on employers. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31989L0391&from=IT. Accessed 18 Feb 2021

Factories and industrial undertakings (safety officers and safety supervisors) regulations (cap. 59, section 7) 1986 Hong Kong https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap59Z?SEARCH_WITHIN_CAP_TXT=safety%20officer. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

Forsyth DR (2020) Group-level resistance to health mandates during COVID-19 pandemic: a groupthink approach. Group Dyn 24(3):139–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000132

Freudenberger HJ (1974) Staff burn-out. J Soc Issues 30:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1974.tb00706.x

Garrido MV, Bittner C, Harth V et al. (2015) Health status and health-related quality of life of municipal waste collection workers—a cross-sectional survey. J Occup Med Toxicol 10(1):22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-015-0065-6

Givaudan SA (2021) About Givaudan: our global presence. https://www.givaudan.com/our-company/about-givaudan/our-global-presence. Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Government of Switzerland (2020) Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research. Regulation of professions: occupational safety and health. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjVrrDB_dDvAhVrwQIHHfGIDTEQFjAAegQIBBAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.sbfi.admin.ch%2Fdam%2Fsbfi%2Fen%2Fdokumente%2F2016%2F08%2Farbeitssicherheit.pdf.download.pdf%2Farbeitssicherheit_e.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2RdCgVeqG4EgdwxHrj4VN1. Accessed 27 Mar 2021

Government of the United Kingdom (2021) Data Protection Act. www.gov.uk/data-protection. Accessed 13 Jun 2021

Hale A, Booth R (2019) The safety professional in the UK: development of a key player in occupational health and safety. Saf Sci 118:76–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.04.015

Harvey SB, Joyce S, Tan L et al. (2014) Developing a mentally healthy workplace: a review of the literature. https://www.headsup.org.au/docs/default-source/resources/developing-a-mentally-healthy-workplace_final-november-2014.pdf?sfvrsn=8. Accessed 27 Mar 2021

Health and Safety Authority Ireland (2020). What is the role of the safety and health advisor. https://www.hsa.ie/eng/Topics/Managing_Health_and_Safety/Safety_and_Health_Management_Systems/#advisor. Accessed 30 Jan 2020.

Health and Safety Executive (HSE) Network UK (2019) what is IOSH and what do the membership levels mean? https://www.hse-network.com/what-is-iosh-and-what-do-the-membership-levels-mean/. Accessed 18 Mar 2021

Heinemann L, Heinemann T (2017) Burnout research: emergence and scientific investigation of a contested diagnosis. Sage Open 7(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017697154

Hjálmsdóttir A, Bjarnadóttir VS (2020) “I have turned into a foreman here at home”: families and work–life balance in times of COVID‐19 in a gender equality paradise. Gender Work Organ 28:268–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12552

Horton R (2020) Offline: COVID-19—bewilderment and candour. Lancet 395(10231):1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30850-3

HSE UK (2021) Risk assessments https://www.hse.gov.uk/involvement/riskassessments.htm. Accessed 16 Feb 2021

ILO (1981) Occupational safety and health convention, 1981. Convention 155. ILO, Geneva

ILO (2014) A 5 step guide for employers, workers and their representatives on conducting workplace risk assessments. International Labour Organization, Geneva

ILO (2020b) In the face of the pandemic: ensuring safety and health at work. International Labour Organization, Geneva, p. 2020

International Council for Science (2008) A science plan for integrated research on disaster risk: addressing the challenge of natural and human-induced environmental hazards. p. 14 https://council.science/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/irdr-science-plan.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2021

International Labour Organization (ILO) (2020a). Pillar 3: protecting workers in the workplace (ILO Policy Framework for tackling the economic and social impact of the COVID-19 crisis). https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_745337.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct 2021

Ivanov ID (2020) Workplaces’ preparedness response and recovery. Presented at IOSH managing safety and health in response to COVID-19 online 2 April 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mc3fORUas4k&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 02 February 2021

Janis IL (1972) Victims of groupthink: a psychological study of foreign-policy decisions and fiascos. Houghton Miffin, Boston

Kitzinger J (1995) Qual Res. Introducing focus groups. BMJ (Clin Res ed) 311:299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y et al. (2019) Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease. JAMA Netw Open 3(3):e203976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976

Kniffen KM, Narayanan J, Anseel JF et al. (2021) COVID-19 and the workplace: implications, issues, and insights for future research and action. Am Psychol 76(1):63–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000716

Lyon B, Popov G (2019) Risk treatment strategies: Harmonizing the hierarchy of controls and inherently safer design concepts. Prof Saf 64(5):34–4

Madsen CU, Hasle P, Limborg HJ (2019) Professionals without a profession: occupational safety and health professionals in Denmark. Saf Sci 113:356–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2018.12.010

Manuele FA (2014) Advanced safety management: focusing on Z10 and serious injury prevention, 2nd edn. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken

Marques ICDS, Theiss LM, Johnson CY et al. (2020) Implementation of virtual focus groups for qualitative data collectionin a global pandemic. Am J Surg 221(5):918–922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2020.10.009

Matthews KL, Baird M, Duchesne G(2018) Using online meeting software to facilitate geographically dispersed focus groups for health workforce research Qual Health Res 28(10):1621–1628. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318782167

McFarlane AC, Bryant RA (2007) Post-traumatic stress disorder in occupational settings: anticipating and managing the risk. Occup Med 57:404–410. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm070

Middlesex University London (2020) https://www.mdx.ac.uk/study-with-us/autumn-2020-coronavirus. Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Morera LP, Gallea JI, Trógolo MA et al. (2020) From work well-being to burnout: a hypothetical phase model. Front Neurosci 14:1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00360

National Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) (2015) Hierarchy of controls. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/hierarchy/default.html. Accessed 18 Feb 2021

North CS, Surís AM, Pollio DE (2020) A nosological exploration of PTSD and trauma in disaster mental health and implications for the COVID-19 pandemic. Behav Sci 11(7):1–14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11010007

Office of National Statistics (2021) ONS occupational coding tool. https://onsdigital.github.io/dp-classification-tools/standard-occupational-classification/ONS_SOC_occupation_coding_tool.html. Accessed 8 Oct 2021

Osborn AF (1953) Applied imagination: principles and procedures of creative problem-solving. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1953 (rev. 1957, 1963)

Parington R (2020) New Furlough Scheme: how does it work and who will benefit? The Guardian. 9 October 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/oct/09/new-furlough-scheme-how-does-it-work-and-who-will-benefit. Accessed 14 Mar 2021.

Peeri NC, Shrestha N, Rahman MS et al. (2020) The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol 49(3):717–726. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyaa033

Restauri N, Sheridan AD (2020) Burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder in the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic: intersection, impact, and interventions. J Am Coll Radiol 17:921–926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.05.021

Robin L (2021). Who’s Who L. Robin. https://www.cambridgeshireandpeterboroughccg.nhs.uk/about-us/whos-who/dr-liz-robin/. Accessed 20 Mar 2021.

Shaw J, Day T, Malik N et al. (2020) Working in a bubble: how can businesses reopen while limiting the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks? CMAJ 192(44):E1362–E1366. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.201582

Swain KA (2012) Explanation of risk and uncertainty in news coverage of an anthrax attack. JRACR 2(2):81–85. https://doi.org/10.2991/jracr.2012.2.2.1

Tates K, Zwaanswijk M, Otten R et al. (2009) Online focus groups as a tool to collect data in hard-to-include populations: examples from paediatric oncology. BMC Med Res Methodol 9:15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-9-15

Teti M, Schatz E, Liebenberg L (2020) Methods in the time of COVID-19: the vital role of qualitative inquiries. Qual Res 19:1–5. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920920962

Thomas D, Mulville M, Hare B (2019) The identification of the domestic waste collection system associated with the least operative musculoskeletal disorders using human resource absence data. Resour Conserv Recycl 150:104424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2019.104424

Toderi S, Balducci C (2015) HSE Management Standards indicator tool and positive work-related outcomes. Int J Workplace Health Manag 8(2):92–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJWHM-11-2013-0044

Trade Union Congress (2020) Many UK workplaces still not “Covid-Secure”—TUC poll reveals https://www.tuc.org.uk/news/many-uk-workplaces-still-not-covid-secure-tuc-poll-reveals. Accessed 19 Jan 2021

University of Aberdeen (2020) Research culture task and Finish Working Group. https://www.abdn.ac.uk/research/support/activities-to-date-657.php. Accessed 13 Jun 2021

Vision Zero (2021) 7 Golden Rules and 4 Principles of Vision Zero. https://visionzero.lu/en/7-golden-rules/. Accessed 16 Jun 2021

Walke HT, Honein MA, Redfield RR (2020) Preventing and responding to COVID-19 on college campuses. JAMA 324(17):1727–1728. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.20027

Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG et al. (2020) A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 395(10223):470–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30185-9

WHO (2020) WHO Director-General’s opening remarks st the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-11-march-2020. Accessed 18 Jan 2021

WHO Europe (2020a) Guidance for pandemic preparedness https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/communicable-diseases/influenza/pandemic-influenza/pandemic-preparedness/guidance-for-pandemic-preparedness. Accessed 3 Feb 2020

WHO Europe (2020b) Strengthening and adjusting public health measures throughout the COVID-19 transition phases: policy considerations for the WHO European Region. WHO Europe Document number WHO/EURO:2020-960-40425-45211, Copenhagen, Denmark

WHO Europe (2020c) How to counter pandemic fatigue and refresh public commitment to COVID-19 prevention measures. https://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-determinants/behavioural-and-cultural-insights-for-health/news2/news/2020/10/how-to-counter-pandemic-fatigue-and-refresh-public-commitment-to-covid-19-prevention-measures. Accessed 26 Jul 2021

WHO Europe (2020d) Pandemic fatigue: reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-19. WHO Europe Document number WHO/EURO:2020-1573-41324-56242, Copenhagen, Denmark

Williams JS (2002). Depression, PTSD, substance abuse increase in wake of September 11 attacks. NIDA Notes. National Institute of Drug Abuse. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2002/11/depression-ptsd-substance-abuse-increase-in-wake-september-11-attacks. Accessed 7 Feb 2021

Workplace Health and Safety Act r. 9 (2007) Singapore https://sso.agc.gov.sg/SL/WSHA1920-RG9. Accessed 20 Mar 2021

World Economic Forum (2020) The future of jobs report 2020. https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020. Accessed 13 Jun 2021

World Health Organization (WHO) (2019) Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases. Accessed 16 Feb 2021

Wright N, Hollohan J, Pozniak E et al. (2019) The development of the occupational health and safety profession in Canada. Saf Sci 117:133–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2019.04.005

Xiang YT, Yang Y, Li W et al. (2020) Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet 7(3):228–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30046-8

Yamey G, Walensky R (2020) Covid-19: re-opening universities is high risk. BMJ 370:m3365. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3365

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Ethical considerations

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gold, D., Hughes, S. & Thomas, D. Perceptions, experiences and opportunities for occupational safety and health professionals arising out of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 271 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00955-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00955-y

This article is cited by

-

Progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals has been slowed by indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)