Abstract

The ICT revolution has impacted the way diasporic groups and individuals communicate and interact with one another. Diasporas are now fueled by unlimited flows of digital contents generated by daily activities or sudden historical events. As a natural result, the science of migration has evolved just as much as its own subject of research. Thus, dedicated branches of research like digital diasporas emerge at the crossroad between fields of social and computational sciences. Thereupon, new types of multi-scale reconstruction methods are developed to investigate the collective shapes of digital diasporas. They allow the researchers to focus on individual interactions before visualizing their global structures and dynamics. In this paper, we present three different multi-scale reconstruction methods applied to reveal the scientific landscape of digital diasporas and to explore the history of an extinct online collective of Moroccan migrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 1985, A. Sayad documented an unexpected use of cassette tapes: the mother of a young emigrant was regularly exchanging recorded voice messages with her son instead of writing him letters (Sayad, 1985). The recording system objectified her words by making them more spontaneous and tangible. Through this technical mean of communication, mother and son were experimenting a new way of keeping long-lasting their remote presence beyond borders.

Modern migration studies have established that migrant people were the actors of a culture of bonds (Diminescu, 2008). Organized in diasporas, migrants place themselves in the center of complex transnational networks by feeding economical connections, maintaining family relations, weaving cross-cultural identities or gathering pieces of collective memories. From the 1980s to the 1990s, migrants demonstrated their ability to take advantage of information and communication technologies (ICT); ahead of their time, they ended up facing the 2000s’ digital shift (Appadurai, 1996).

The ICT revolution has impacted our modern societies as a whole (Borgman, 2003). However, the birth of this new world of digital traces has also influenced the way diasporic groups and individuals communicate and interact with one another (Risam, 2018). Diasporas are now fueled by unlimited flows of digital contents (text messages, social networks footprints, hypertext citations, etc.) generated by daily activities or sudden historical events (Arab Spring, refugee crisis, natural disasters, etc.) (Heller and Pezzani, 2014; Lobbé, 2018). Existing migrant communities are therefore enriched by a wide variety of digital layers: from structured networks of migrant Web sites to fuzzy WhatsApp groups (Dekker et al., 2018; Diminescu, 2012); hence completing the evolution of earlier forms of diasporic organizations.

As a natural result, the science of migration evolved just as much as its own subject of research. Scientific publications’ online databases are scaling up and one can now browse through the amazing richness of multidisciplinary archives. Researchers also integrate large and heterogeneous data sets within their own observations’ scope like scrapped Web contents or late-digitized corpora of texts (Ben-David, 2012; Ceserani et al., 2017). However, if dealing with digital sources remains a technical and methodological issue, we must not forget that guaranteeing the quality of a sparse and mixed set of documents might be even more difficult.

Dedicated fields of research have thus emerged and settled at the crossroad between social and computational sciences. This is the case of digital diasporas(Candidatu et al., 2019) for instance, a field aiming to bring the questions of cross-language, cross-platform and cross-cultural concerns to the fore of migration studies by following quali-quantitative insights and socio-technical approaches.

In this article, we want to investigate digital diasporas both as a domain and object of research. However, how can we picture, in a meaningful way, an entire research community as well as some of its most representative publications? Is there a family of scientific methods capable of achieving such goal? Can we also apply these methods to the very own research subject driving the targeted scientific community?

As an answer, we will follow a macro to micro investigation path, a multi-scale movement. We will first reconstruct digital diasporas as a global scientific landscape shaped by interdisciplinary publications. We will then focus on the historical evolution of one of its sub-domain: a particular research branch influenced by the connected migrant figure and focusing on online representations of diasporas. We will finally give an example of a study conducted within the scope of this branch, a study trying to reconstruct the collective shape of a given diaspora from all the various digital traces produced by its own members.

A specific multi-scale reconstruction method will be applied to each section of this article, as these methods (see section “Multi-scale reconstruction methods”) are well suited to reveal dynamical and structural aspects of any collective organizations: from communities of researchers to online networks of migrant Web sites. We will use a semantic map for section “The scientific landscape of digital diasporas”, a phylomemy for section “The emergence of a socio-technical branch”, and explain how Web fragments were used to produce the results of section “Reconstruction of an extinct online migrant collective”. Our article will thus have value for researchers looking for an overview of digital diasporas’ research as well as a practical application of multi-scale reconstruction methods within the scope of migration studies. We think that the future of digital diasporas as a research domain might be influenced by the promotion of these methods. Digital diasporas is certainly an effervescent fieldFootnote 1 that grows in maturity by following promising insights; the present article have to be seen in relation to this vibrant context.

Multi-scale reconstruction methods

Today’s diasporas are human artifacts driven by flows of informational data whose global shapes convey their own elements of knowledge (Chavalarias, 2019). In the same way as ants or bees, human societies are built upon a phenomenon called collective intelligence: the aggregation of individual traces that help to achieve complex tasks (Bonabeau, 1994). One of its core mechanism is known as the stigmergy: i.e., the indirect coordination between an agent and an action through the environment (Theraulaz and Bonabeau, 1999). The e-Diasporas Atlas for instance, was a pioneer work dedicated to the exploration of such a stigmergic environment: it revealed networks of migrants Web sites connected one another by means of hypertext links (Diminescu, 2012).

We, therefore, call reconstruction methods the generic techniques used to reveal the collective shapes of such structures. Some of these methods have been historically developed within the very scope of migration studies while others have been influenced by complex systems science. However, all of them have grown upon multidisciplinary foundations and share a fundamental multi-scale property. They indeed allow researchers to switch from one scale of observation to another, to focus on individual interactions, as well as collective and global organizations. Multi-scale reconstruction methods can be defined as follows: understanding a natural phenomenon or a complex object by means of both the observation of patterns and analysis of processes. Multi-scale reconstruction methods are then part of the larger family of phenomenological reconstructions, which consist in finding reasonable approximations of structures and dynamics of a phenomenon, so that it could eventually be studied by researchers (Bourgine et al., 2009).

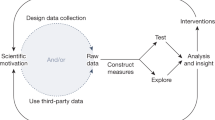

Multi-scale reconstruction methods’ generic workflow

We start by choosing a complex object O and selecting the properties we want to observe and measure. Next, we collect an accurate set of data (e.g., some digital traces of migration) that are later used to reconstruct the targeted properties as a formal object R described in a high-dimensional space (Chavalarias et al., 2020). We finally apply a dimensional reduction on R to get a human-readable visualization V, which will be analyzed by the researcher in the end (Lobbé et al., 2020). The reconstruction chain O ↦ R ↦ V is an iterative process where each step can be refined in light of future outcomes.

Reconstruction methods concretely require the use of dedicated software embedded within larger socio-technical protocols. Some methods are already fully usable by sociologists, historians or philosophers; others still remain at a prototype stage and call for complex engineering handling. They are based upon textual data: either late-digitized traces (letters, books, audio transcriptions, etc.) or born-digital traces (Web pages, Web archives, social media posts, etc.), but pure images and video are unfortunately not yet taken into account. Let us now define the three methods we are about to experiment: the semantic maps, the phylomemies and the Web fragments.

Maps

We broadly call map the graphical outcome V of the reconstruction as a network R of a set of actors O interacting within a given environment. Usually taking the shape of a graph, such maps might represent networks of people sending letters one another, just as much as words semantically related within a chosen corpus of texts. The use of networks in social science is an already long-established technique (Moreno, 1934), but the most recent progress in the field of complex systems have enriched it by taking on board mixed multi-scale interactions (Delanoe et al., 2014).

Various mapping tools are thus already available and some strong research protocols have yet been successfully fulfilled in the context of migration studies. Among others, the e-Diasporas Atlas (Diminescu, 2012) used maps of migrant Web sites to reconstruct the online representation of thirty different diasporas: the relevant Web sites were semi-manually collectedFootnote 2 before being aggregated as a set of collective networks through the software Gephi(Bastian et al., 2009). As for them, semantic maps are maps dedicated to the visualization of networks of terms, expressions or concepts. They can be reconstructed within the software Gargantext where large corpora of documents are processed by means of text-mining algorithms (Delanoë et al., 2020). Extracted words are thus projected in a multi-dimensional semantic landscape and late visualized through Gephi (see section “The scientific landscape of digital diasporas”).

Phylomemies

The phylomemy reconstruction aims to investigate the temporal dynamics of a given corpus of textual documents (Chavalarias and Cointet, 2013; Chavalarias et al., 2020) by revealing the internal evolution of its vocabulary. As well as being constructed upon strong mathematical foundations, phylomemies have also been influenced by social sciences concerns as they are part of the co-word analysis framework (Callon et al., 1991). Phylomemies have recently been enriched with a set of multi-scale properties and can now encompass several levels of aggregation (Chavalarias et al., 2020).

To that end, the researcher first chooses the scope of her corpus O by constructing an home-made database or by requesting an existing one (e.g., an online collection of scientific publications). Within the free software GargantextFootnote 3, she semi-manually selects a set of terms called map list that she later uses as foundations to the upcoming reconstruction. Next, text-mining algorithms find groups of terms jointly used during a shared period of time. An inter-temporal matching is then applied between these groups from one period to another in order to reconstruct their kinship relations R. This results in a complex formal object called foliation. The researcher is finally able to reduce this foliation to visualize all the branches of inter-connected groups as an evolutionary representation V of the internal dynamics of her corpus. Within Gargantext, the researcher can browse the phylomemy from a neophyte to an expert-oriented visualization (see section “The emergence of a socio-technical branch”).

Web fragments

The Web fragments framework is dedicated to the exploration of corpora of Web archives. A Web fragment is a semantic and syntactic subset extracted from a given archived Web page (Lobbé, 2018). It’s a coherent set of textual, visual, audio or animated contents. A Web fragment should be comprehensible on its own and must go with an associated set of scrapped meta contents: an author, a title, an edition date, etc.

First of all, the researcher frames the scope of her corpus of Web archives O in terms of temporality, frequency and area (list of Web sites and pages). She then defines one or more Web patterns by selecting coherent sequences of HTML elements that will be used to create the shapes of the upcoming Web fragments. This could define an article, a post on a social media or a set of commentaries written under a given video. Next, an automatic process extracts the Web fragments from the archives and determines the most accurate timestamp for each of them. This results in the reconstruction of the original temporal structure of the corpus as a collection of Web fragments R stored within a dedicated search engine. Finally, the researcher has to query the engine and requests a subset of Web fragments, which she will be able to visualize by means of a map or a phylomemy V.

The Web fragments framework as described above is still at a prototype stage and requires strong engineering skills to be fully handled (Lobbé, 2018) (see section “Reconstruction of an extinct online migrant collective”).

The scientific landscape of digital diasporas

Digital diasporas as a research domain is an emerging field that falls within the larger scope of migration studies. Like several contemporary fields, digital diasporas covers a wild variety of mixed subjects and practices that are challenging to depict as a whole. In what follows, we will use a semantic map to reconstruct the scientific landscape of digital diasporas. By doing so, we will corroborate the observations of past works (Pisarevskaya et al., 2020; Porter and Rafols, 2009) that already have shown the recent hybridization of migration studies—and science as whole—due to interdisciplinary research conducted at the edges of classical tracks. However, unlike these past works, we will focus on the textual content of the publications—without any citations data (Porter and Rafols, 2009)—and reveal their semantic evolution in a continuous way (see section “The emergence of a socio-technical branch”), as an alternative to existing temporal series of topics (Pisarevskaya et al., 2020).

Corpus

We start by broadly defining the scientific borders of digital diasporas with a set of generic keywords such as migration, diasporas, smartphone or digital technologies before building a more complex queryFootnote 4. This query is then used for browsing through the related literature available in academic databases. We first elect the Web of science (Wos) as a starting point for reconstruct a landscape of digital diasporas’ research—the Wos has the advantage of being accessible online and covers a wild variety of international journals in the field of social sciences and sociology. We consolidate this primary perimeter by combining it to the English language section of the french Hyper Articles en Ligne (Hal) database. We limit our harvesting to English written papers because, in its current stage of development, Gargantext cannot deal with cross-language contents. Furthermore, though scientific databases provide poor quality meta-data for papers published before the 1990s, we think that digital diasporas’ publications are barely concerned by this biasFootnote 5 as they have been mainly written after the 2000s. By doing so, we retrieve from Wos and Hal a collection of 2106 papers and their meta-data (titles and abstracts) that we later reduce with a manual pruning to a definitive corpus of 1562 documentsFootnote 6 published between the 1980’s and April 2020. As most of the scientific databases are unfortunately still not open-access, we recognize that our corpus couldn’t be considered as fully representative (English written papers only, well established journals, etc.), but we make the assumption that the resulting landscape will yet give evidence of the main digital diasporas’ research trends. Our method indeed focuses on vocabulary uses from a statistical point of view, which means that even if we have omitted an important paper, we might eventually catch its ideas and concepts because they have spread among contemporary publications and thus have influenced the whole semantic evolution of the field.

Within Gargantext, we next select a list of 325 termsFootnote 7, expressions or concepts extracted from the meta-data of all the papers. We use these terms as foundations for the upcoming semantic map by asking Gargantext to calculate their corresponding distributional similarity. The distributional similarity is a linguistic metric used to study terms that belong to the same class of meanings (Gaume, 2004). Here, it leads to the creation of a paradigmatic landscape, i.e., it highlights the similarity between fields of research that are sharing the same methodologies, although they focus on different objects of study. The resulting map aims to reveal all the research communities that make up the digital diasporas by sharing common practices.

A cross-disciplinary domain of research

The Figure 1 shows the reconstructed scientific landscape of digital diasporas. This is a graph where academic terms are represented by dots connected one another thanks to the strength of their distributional similarity. The size of the dots depends on the value of a page rank calculated by Gephi to highlight the most central terms. We number six main clusters (Fig. 1, cluster No.1 to No.6), i.e., groups of terms strongly connected to each other, but poorly linked with the rest of the network. We now review all these clusters and their corresponding communities.

The digital diasporas is a model of fragmented domain of research. It grows at the crossroad between anthropology, media studies, sociology and computer sciences and brings their respective practices to the fore of migrations issues. However, the whole community does not seem to arrive at a consensus concerning the meaning of digital diasporas as a terminology. Indeed, the cluster containing the terms digital diasporas (cluster No. 3) is sparse and somehow central though secondary in the map. Digital diasporas can in fact be seen as a modern label introduced to cover all the transformations of human migrations induced by the use of digital technologies (Bernal, 2014). It aims to highlight hybrid researches that question the diasporic-self of migrant people regarding new forms of cross-cultural identity, digital spatiality and online organization (Candidatu et al., 2019; Ponzanesi, 2020). Despite the blurry borders of digital diasporas the map still witnesses an intense and vibrant scientific activity from classical sociological approaches to digital-born methodologies.

For instance in cluster No. 4, the specificity of digital communication (memes, gifs, emojis, etc.) is investigated regarding multi-language concerns (Artamonova and Androutsopoulos, 2019), media studies and technical design practices. This new form of semiotic complexity gives promising insights to explore today’s hybridization of migrations. Indeed, with the digitization of human interactions the figure of the migrant has evolved to become more unpredictable and complex (Diminescu, 2008). The characterization of diasporic groups now results from the aggregation of their individual and collective traces produced by their relations one another and with the whole society.

Thereupon, the scientific community embodied by cluster No. 5 makes an intensive use of tweets and social media data to study the relations between migrations and political mobilizations. They analyze political public discourses or the evolution of elements of vocabulary that circulate within the media sphere. They focus on major historical events (Arab spring, Syrian war, refugee crisis) through the lens of extracted textual contents that are later processed by data mining techniques (Dekker et al., 2018; Rohde et al., 2016). Owing to the ICT revolution, our societies are now able to follow the live proceeding of these crisis and the 2000’s digital shift has disrupted the classical notions of public spaces, debates and discourses. Pro- and anti-migrants face each other on the Web Digital technologies have increased the capacity for migrant and non-migrant people to become actors of national and international political actions (Siapera, 2019; Thomas et al., 2019).

However, the unprecedented amount of data produced by wars and crisis does not only consist of tweets and facebook posts; the researchers of cluster No. 5 also investigate the status of humanitarian data in the context of emerging forms of technocolonialism and technological solutionism (Madianou, 2019; Morozov, 2013). An asylum seeker might thus be the source of a huge volume of personal data whose property and exploitation induce security, political and mercantile concerns (Macias, 2019).

From another angle, the personal data of young migrant people become in cluster No. 2 the key to investigate their own digital spaces (Baran, 2018; Lorenzana, 2016). Immersed in our information societies, these individuals are facing a continuous transformation of their cultural identities. Sociologists and anthropologists there investigate the way the smartphones are merging and blowing away the borders of old diasporic heritages and past collective memories. There is no more immutable identity but a set of complex and moving cross-cultural constructions. Researchers use interviews and participant observations to question the self-representation of second generation migrants, young refugees or woman workers in light of their social media habits (Peile and Hijar, 2016). The digital contents, that one chooses to follow or promote with her mobile device, are scientific materials later analyzed to reconstruct individual narratives. The understanding of such virtual self-spaces might be a key to avoid social isolation or marginalization (Zhang, 2013).

On the contrary, researchers from cluster No. 1 distance themselves from individuals to put migrant people back in the center of their social networks (Giulietti et al., 2013). There, migrants are considered as actors interacting within a complex environment where they can develop strong and weak ties from home countries to host societies. By the end of the 1990’s, new means of communication like cell-phones, online messages or voice recordings enriched the access capital of diasporic groups. Shortly afterwards, sociologists demonstrated how migrant people were able to use such devices to consolidate their personal networks beyond borders (Diminescu, 2002; Impey, 2013). Social network analysis thus benefited from the addition of digital data exploration mixed with long-established social sciences methodologies: surveys, semi-structured interviews or focus groups. Nowadays, digital diasporas keep up investigating classical concerns of migration studies (geographical mobility, gender issues, social capital, etc.) through the lens of social network theory (Pathirage and Collyer, 2011; Shakhsari, 2011). However, its encounters with large and automatic network analysis techniques, promoted by computer sciences, still remains an open challenge: specific vocabularies and approaches have to be shared.

One community, however, succeeded in creating a fully hybridized research methodology. Gathered around the outcomes of the e-Diasporas Atlas, scientists from cluster No. 6 are conducting digital-born analysis on top of crawled and archived Web materials. We will next use the phylomemy reconstruction to highlight the history of this community.

The emergence of a socio-technical branch

We now move to a diachronic representation of digital diasporas’ scientific landscape by means of a phylomemy. We therefore switch from a macro to mezzo scale of observation to understand the temporal relationships between the various digital diasporas’ research branches. To that end, we reuse the corpus and the list of terms previously shaped (section “Corpus”) and we ask Gargantext to distribute the papers among constant periods of time. Within each period, a set of text-mining algorithms extracts groups of terms frequently used together by the researchers (Chavalarias et al., 2020). A temporal matching task then weaves kinship connections between these groups throughout time. It results in the creation of a phylomemy made of 222 terms, 156 groups and 26 branches. The phylomemy has to be read from top to down, from the past to the present days. There, groups of terms are represented by dots and we call branch a full set of groups connected by kinship lines. Such a lineage is made to reveal the evolution of a sub-field of research. The Fig. 2 displays the overall shape of the phylomemy and is manually annotated to facilitate its readingFootnote 8.

The phylomemy bears witness of the progressive integration of ICTs data among classical migration studies from the 1980’s to the 1990’s (group No. 5). The 2000’s digital shift then brought its share of diasporic traces; used shortly afterward to enrich the analysis of social networks and migrant trajectories (group No. 4). New structured branches appeared in the late 2000’s by bringing to the fore cross-languages concerns (group No. 1), while interests for digital self-spaces and identities had to wait until the present days to become incredibly investigated by the community (group No. 2). For its part, the socio-technical branch we now want to focus on (group No. 3) has grown alongside it’s own subject of research; namely, the diasporic Web.

At the beginning of the 2000’s, the Web and its constitutive elements (sites, forums, databases, etc.) slowly became a source of scientific materials for the comprehension of migrations (Tyner and Kuhlke, 2000; Van den Bos and Nell, 2006). Simultaneously, the dedicated research group TIC-Migration appeared under the coordination of the sociologist D. Diminescu (Diminescu, 2008). Altogether, they wanted to investigate the new communication habits of diasporic groups and, among others, the singular status of hundreds of migrant Web sites and their digital-born mechanism of citation: the hypertext links. Incorporated within complex networks of pages and online resources, these Web sites were diasporic hubs, places to share collective memories or vectors of political claims (Scopsi, 2009). By navigating throughout hypertext citations, it was at the time possible to explore wide constellations of Web territories. Visit after visit, personal Web sites of migrant individuals ended up as essential portals for entire diasporic communities.

After a decade of pioneer insights, the TIC-Migration group widened to become a collective of 80 researchers and engineers who then focused on the creation of the e-Diasporas Atlas (Diminescu, 2012). The Atlas was an unprecedented effort to cartography thousands of migrant Web sites related to tens of diasporasFootnote 9. A migrant Web site was defined as a Web site created or managed by migrants or that was dealing with them. An e-Diaspora was, for its part, a network of migrant Web sites connected one another by hypertext links. It was a migrant collective that organized itself first and foremost on the Web. In order to build the Atlas, the researchers made up an innovative socio-technical protocol at the crossroad between social and computational sciences. For instance, the software Gephi came out of these dedicated developments and, from that moment, has kept influencing many reconstruction methodologies like semantic maps or to a lesser extend phylomemies.

But back in the early 2000’s, while they were investigating the diasporic Web, researchers frequently witnessed the total or partial disappearance of some of their targeted Web sites. Indeed, the Web has always been an ephemeral environment where entire online collectives can vanished in the blink of an eye. As a matter of fact, it was decided to enrich the e-Diasporas Atlas with a Web archival section (Laflaquière et al., 2005). Thanks to the french National Audiovisual Institute (INA), all the sites indexed by the Atlas were thus automatically archived in dedicated databases.

Since 2015, new researches have finally begun to dive into this corpus of millions of migrant Web archives. The resulting studies question the evolution of the divers e-Diasporas regarding Web uses, languages and historical events. The Web fragment method makes it now possible to navigate across the internal dynamics of migrant Web sites’ archives and follow online cultural changes throughout time.

Reconstruction of an extinct online migrant collective

After having pictured the whole landscape of digital diasporas’ studies and traced the particular history of the e-Diasporas’ community, our article will finally fulfill its review by moving to a micro scale of observation. We will go through an example of socio-technical analysis that succeed in exploring the e-Diasporas Atlas’ corpus of Web archives. By using the Web fragment methodFootnote 10, this study has reconstructed the temporal evolution of the Moroccan e-DiasporaFootnote 11: an online migrant collective originally analyzed by D. Diminescu and M. Renault.

The Moroccan e-Diaspora

Mapped in 2008, the Moroccan e-Diaspora is a network of 156 Web sites connected by 397 hypertext citations. Mostly written in french, the sites are divided in three categories: 1. associations and NGO’s pages, 2. institutional and governmental platforms, and 3. individual blogs. We count 47 blogs that are covering a wide number of themes, such as local development, national politics, intimate stories or daily life considerations.

Ten years later, the Moroccan e-Diaspora has irreversibly changed. Indeed, if we focus on the state of the blogosphere after rediscovering it in 2018, we effectively count 19 dead blogs, 23 abandoned ones and only 5 still aliveFootnote 12.

We are facing the remnants of an extinct online collective, which has partially died out and a question comes to light: what happened to the dead Moroccan blogs in the course of the past decade? For the moment, two hypothesis can be formulated: 1. the blogs have purely and solely vanished; their owners, communities and contents are now out of the Web; 2. the blogs have been changed into something else or have migrated somewhere else.

With this in mind, is there a way to find the past traces of this disappearance and reconstruct the history of the dead Moroccan blogs? Hopefully, the e-Diasporas Atlas and, by extension, these blogs have been conscientiously archived by the INA between 2010 and 2014.

Web archiving and Web fragments

Web archiving is almost as old as the Web itself. Popularized by the Internet Archive and its Wayback machine since 1996Footnote 13, today’s Web archives are maintained by national libraries, private companies, noncommercial initiatives or citizens (Brügger and Milligan, 2018; Musiani et al., 2019). Some corpora are public and freely available for consultation, while others are closed or restricted for research purposes, such as the e-Diasporas one. Broadly speaking, a Web archive can be pictured as a screenshot of a Web page taken by a robot—called crawler—at a specific moment of time and stored within a dedicated database. The resulting shape of a corpus of Web archives depends on both the crawling mechanism and the storage techniqueFootnote 14. In what follows, we refer to the specific INA’s crawler and DAFF file format (Drugeon, 2005). At the INA, in order to archive an entire Web site, the crawler has to frequently collect all its constituent pages provided they evolve since their last harvesting (Lobbe, 2018). For instance, a comment might have been added and a post might have been deleted. A Web archival process thus requires considerable engineering handling and might also induce quality, coherence or timestamping issues.

We first extract from INA’s corpus the archives of the blogs captured between 2010 and 2014. To complete our primary source of data, we enrich them with a side collection from Internet Archive, for the period ranging from 2014 to 2018. The resulting set of hundreds of thousands of Web records are then fragmented by a dedicated engine, which gives us the possibility to query Web fragments published until 2006Footnote 15. Indeed, by using the Web fragments framework, we are able to extend the temporal scope of a sparse corpus of Web archives and reconstruct its lost continuity.

As previous studies suggested the possibility of a mutation of migrant blogs into new forms of social media (Khouzaimi, 2015), we then focus our investigations on Web fragments that could include traces of social network. We thus use pattern matching and regular expression techniques to retrieve the most accurate fragments. In other words, we look for all the facebook comments, twitter widgets or youtube links that might be contained inside the archives of the blogs: within the HTML code or among the CSS style sheetsFootnote 16 Finally, the resulting fragments are temporally sorted and then manually analyzed.

The traces of a digital mutation

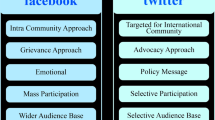

When blogs started to embed social media mechanisms within their own architectures, traces of social network accounts came in their internal code: i.e, a like button was somehow always linked to a unique facebook or twitter account. Nowadays, these technical clues bear witness of a time when digital borders between old blogs and new type of social media were not so distinct, a time when blogs owners started to share their original contents by means of social features. By following the same insight throughout the Web fragments, we are thus able to find 33 social media accounts still used in 2018 and connected to 20 of the dead Moroccan blogs as shown by Fig. 3.

Twitter and facebook outshine this new distribution of social media accounts, while youtube and pinterest remain kite confidential. Owing to a wide offer of social media, we notice that the diffusion of online diasporic contents is now fragmented and specialized by expression means or target audience. A given diasporic content can be first live recorded and published on youtube before being shared on twitter, rather than just being written online on a blog. However here, we have to warn our readers that our methodology cannot be considered as exhaustive. Indeed, if the owners of the dead blogs did not choose to link their old Web sites with their new social networks, we are therefore not able to find traces within the Web fragments. We will thus pay attention to the global tendencies.

The Moroccan blogosphere is well and truly an extinct online collective: the blogs are de facto no longer there. However, instead of a total disappearance, we reveal that the owners of the blogs have moved from one Web territory to another, from the space of the blogs to the space of social media. The Fig. 4 highlights this digital migration from the left to the right, where 2008’s blogs (circles) step down in favor of 2018’s social networks (squares).

There, the topology of the past blogosphere has been recreated. Indeed, if we focus on the 2018’s twitter accounts, we see that both the follower/following connections (Fig. 4, red links) and the old hypertext links (blue links) are overlaid on each other. By using a measure of densityFootnote 17, we reveal that the internal connectivity of the community has increased by going from 0.16 on the blogs to 0.24 on twitter. We are next able to approximate the country of originFootnote 18 of the followers of each of the new twitter accounts to check that the diasporic property of the blogosphere has also been imported. The Fig. 5 thus displays the distribution of each twitter community by country of origin. On the whole, the new twitter accounts are followed by a large proportion of Moroccan people and foreigners or migrants living abroad, as we count 10 other nationalities. In detail, we use the Web fragments to show that, at least, 15% of the people who commented 26% of the posts published on the political blog larbi.org in 2008 have been following its new twitter account in 2018.

So during this digital migration, the owners of the past diasporic blogs have imported their own community with them on twitter. The major part of this extinct collective has thus started over on new social media by preserving their past digital identities (pseudonyms, avatars, contents, etc.). The Moroccan e-Diasporas is somehow still there online, despite all its subsequent mutations. Some key forums and hubs of the network have faced many external shocks and yet outlive the rest of the collective, such as yabiladi.com and bladi.net. Their ability to gather the daily life of Moroccan emigrants might be the key of their longevity.

However, we would have difficulty to say why the digital migration of the blogs occurred. Some clues found inside the Web archives might indicate that the Moroccan part of the Arab spring could have played a major role, but it is insufficient to draw a general conclusion. A plausible answer could be here the conjunction between political events and the historical tendency of the Web to prevail social media over old blogs. Qualitative interviews of the blogs owners may give us new insights in the future.

Discussion

The multi-scale reconstruction methods used in section “The scientific landscape of digital diasporas” and section “The emergence of a socio-technical branch” are generic by nature. They can be applied for reconstructing the landscape and history of any research domain as long as we can access to related textual contents like a corpus of publications. In what follows, we will rather discuss ways of applying such methods to the research objects and topics of digital diasporas in the manner of section “Reconstruction of an extinct online migrant collective”. How can integrate these methods within the scope of classical migration studies? How can they enrich and complete qualitative analysis?

Multi-scale methods of reconstruction are quali-quantitative by nature. They first have been historically influenced by social sciences before using computer sciences to grow up and investigate larger corpora. However, such methods should not be considered as magical solutions. They have to be integrated into socio-technical protocols and implemented in collaboration with researchers and engineers. A socio-technical protocol is a scientific workflow that strives for analyzing wide and heterogeneous cultural data sets in the light of social sciences knowledge. Even if the means are usually technical, the outcomes have to be equally defined and understood by technical and non-technical scientists. At every stage, one should be able to act regarding its own domain-specific knowledge and conduct any qualitative validation of the quantitative results. For instance, half of the tasks fulfilled to obtain the visualizations of section “The scientific landscape of digital diasporas” and section “Reconstruction of an extinct online migrant collective” are the results of qualitative manipulations and expert knowledge.

Like microscopes or telescopes, multi-scale reconstruction methods are scientific tools of observation. A socio-technical protocol that would be using such methods, should therefore follow an iterative process. That is, a workflow where each transitional outcome can be refined or questioned in light of new insights, a workflow where the data analysis process does not break the link with the original sources. Reconstruction methods are thus flowing and reversible: it is always possible to go back and read the original documents. While classical exploration methodologies (Fry, 2004; Tukey, 1977) gradually transform the corpora into orphan visualizations, the O ↦ R ↦ V chain (section “Multi-scale reconstruction methods”) guarantee a new form of continuous tangibility with the digital traces (Lobbé et al., 2020). Reconstruction methods give an overview of the collective shapes of complex objects; and in the same time, they allow to focus on specific individual interactions. However here, we must also avoid the black box effect of software by deconstructing their operations, finding comparable measures and enabling the repeatability of results.

Actually, the implementation of a socio-technical protocol is a question of epistemological translation. Is there a way to create a common scientific language for conducting cross-disciplinary researches, without dealing with the prevalence of one domain over another? Can we create a cross-dictionary of scientific concepts from technical concerns to social sciences involvements? A promising insight might be to include, within our protocols, researchers trained to make scientific translations from one community to another and able to use cross-disciplinary methods. We can already draw our inspiration from ad hoc experiments, such as the e-Diasporas Atlas and its recent outcomes. The digital diasporas as a research domain seems therefore to be the perfect field to keep investigating these cross-disciplinary questions.

Conclusion

By using digital diasporas as a common thread, we have reviewed both the emergence of a cross-disciplinary research domain and given an example of how to reconstruct extinct online migrant collective from Web archives. To achieve this goal, we have used a particular family of scientific methods: the multi-scale reconstruction methods whose some originally appeared within the scope of migration studies. Digital diasporas as a research domain has got used to the evolution of ICT and has bring the 2000’s digital shift to the fore of migration studies. Innovative methods such as semantic maps or phylomemies can now be used for investigating new forms of digital migrant traces and the Web fragment framework has paved the way for large quantitative analysis of Web archives.

However, these methods outgrows the scope of digital diasporas. The observation of the scientific landscape of today’s migration studies bears witness of a vibrant community which is, in fact, addressing larger contemporary research questions. Indeed, due to the pandemic of COVID-19, our societies have been forced to experiment a form of presence beyond distance that was once only reserved to migrant people. During the global lockdown, people have briefly learned how to recreate individual and collective relationships by means of digital devices, in the same way as diasporic groups did ten or twenty years ago. We could thus investigate the upcoming digital habits of 2020’s global humanity in the light of digital diasporas methodologies; and by doing so, influence the future of social sciences.

Data availability

In section “Corpus”, the full corpus can be downloaded at https://gitlab.iscpif.fr/qlobbe/publication-resources/blob/e694f68c2d599abff9e13ceef074897d9f9b464e/digital-diasporas-2020/corpus.csv and the list of terms can be downloaded at https://gitlab.iscpif.fr/qlobbe/publication-resources/blob/e694f68c2d599abff9e13ceef074897d9f9b464e/digital-diasporas-2020/list.csv. In section “The emergence of a socio-technical branch”, the phylomemy can be downloaded at https://gitlab.iscpif.fr/qlobbe/publication-resources/blob/479d63df22fadaa06bbe51cad86601b61ba5ae54/digital-diasporas-2020/phylomemy.svg.

Notes

See the program of the 2019 Digital Diasporas Interdisciplinary Perspectives conference for a brief overview (https://crosslanguagedynamics.blogs.sas.ac.uk/digital-diasporas/).

See Navicrawlerhttps://medialab.sciencespo.fr/en/tools/navicrawler/.

See the beta version https://gargantext.org/.

The whole query is: “digital diasporas” OR “e-diasporas” OR ((“migration” OR “diasporas” OR “diasporic communities” OR “immigrant” OR “migrant” OR “refugees” OR “transborder” OR “transnational” OR “diasporic”) AND (“digital technologies” OR “social network” OR “social media” OR “new media” OR “information and communication technologies” OR “smartphone” OR “cellphone” OR “telephone” OR “blog” OR “web archives” OR “digital methods” OR “digital platforms” OR “digital humanities”)).

In the Fig. 2, we only have access to the titles of the papers written before 1990.

This section is an extract from a vaster study conducted by Q. Lobbé in 2018 (Lobbé, 2018).

We call dead a blog no longer online and abandoned a blog, which has not been updated since at least 2017.

See the original paper (Lobbé, 2018) for technical details.

A dense graph is a graph in which the number of edges is close to the maximum, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dense_graph.

We use the tweet-location property of the twitter API.

References

Appadurai, A (1996) Modernity al large: cultural dimensions of globalization, volume 1. University of Minnesota Press

Artamonova O, Androutsopoulos J (2019) Smartphone-based language practices among refugees: Mediational repertoires in two families. J für Medienlinguistik 2:60–89

Baran DM (2018) Narratives of migration on facebook: Belonging and identity among former fellow refugees. Lang Soc 47:245–268

Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M (2009) Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. In: Third international AAAI conference on weblogs and social media. San Jose, California USA

Ben-David A (2012) The palestinian diaspora on the web: between de-territorialization and re-territorialization. Soc Sci Inform 51:459–474

Bernal, V. (2014) Nation as network: Diaspora, cyberspace, and citizenship. University of Chicago Press.

Bonabeau, E. (1994) Intelligence collective. Hermes.

Borgman, C. L. (2003) From Gutenberg to the global information infrastructure: access to information in the networked world. MIT Press.

Bourgine P, Brodu N, Deffuant G, Kapoula Z, Müller J-P, Peyreiras N (2009) Formal epistemology, experimentation, machine learning. In: Chavalarias et al. (eds) HAL Archives Ouvertes, https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00392486, pp. 10–14. March 2009. ISBN https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00392486

Brügger N, Milligan I (2018) The SAGE handbook of web history. Sage

Callon M, Courtial JP, Laville F (1991) Co-word analysis as a tool for describing the network of interactions between basic and technological research: the case of polymer chemsitry. Scientometrics 22:155–205

Candidatu L, Leurs K, Ponzanesi S (2019) Digital diasporas: Beyond the buzzword: toward a relational understanding of mobility and connectivity. In: The handbook of diasporas, media, and culture,John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 31–47

Ceserani G, Caviglia G, Coleman N, De Armond T, Murray S, Taylor-Poleskey M (2017) British travelers in eighteenth-century italy: the grand tour and the profession of architecture. Am Hist Rev 122:425–450

Chavalarias D (2019) Formes collectives. Le Genre humain, (1):145–152

Chavalarias D, Cointet JP (2013) Phylomemetic patterns in science evolution-the rise and fall of scientific fields. PLoS ONE 8(2): pp.e54847

Chavalarias D, Lobbé Q, Delanoë (2021) A Draw me science-multi-level and the multi-scale reconstruction of knowledge dynamics with phylomemies. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03180347

Dekker R, Engbersen G, Klaver J, Vonk H (2018) Smart refugees: how syrian asylum migrants use social media information in migration decision-making. Soc Media Society 4:2056305118764439

Delanoë A, Chavalarias, D., and Lobbé, Q. Mining the digital society-Gargantext, a macroscope for collaborative analysis and exploration of textual corpora. Forthcoming

Delanoe A, Chavalarias D, Anglade A (2014) Dematerialization and environment: a text-mining landscape on academic, blog and press publications. In: ICT for Sustainability 2014 (ICT4S-14). Atlantis Press

Diminescu D (2002) Lausage du téléphone portable par les migrants en situation précaire. Hommes Migration 1240:66–79

Diminescu D (2008) The connected migrant: an epistemological manifesto. Soc Sci Inform 47:565–579

Diminescu D (2012) e-Diasporas Atlas: Exploration and cartography of diasporas on digital networks. Ed. de la Maison des sciences de l’homme

Drugeon T (2005) A technical approach for the French web legal deposit. In: 5th International Web Archiving Workshop (IWAW05), Viena, Austria. Citeseer

Fry BJ (2004) Computational information design. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Gaume B (2004) Balades aléatoires dans les petits mondes lexicaux. I3 Inform Interact Intell 4:39–96

Giulietti C, Schluter C, Wahba J (2013) With a lot of help from my friends: social networks and immigrants in the uk. Popul Space Place 19:657–670

Peile CG, Hijar AR (2016) Immigrants and mobile phone uses: Spanish-speaking young adults recently arrived in london. Mobile Media Commun 4:405–423

Heller C, Pezzani L (2014) Liquid traces: Investigating the deaths of migrants at the euas maritime frontier. Rev Eur Migr Int 30:71–107

Impey A (2013) Keeping in touch via cassette: Tracing dinka songs from cattle camp to transnational audio-letter. J Afr Cult Stud 25:197–210

Khouzaimi J (2015) e-diasporas: Réalisation et interprétation du corpus marocain. Télécom ParisTech

Laflaquière J, Gangloff S, Scopsi C, Guignard T, Soultanova R, Salzbrunn M, Beaujouan V, Diminescu D (2005) Archiver le web sur les migrations: quelles approches techniques et scientifiques? rapport d’étape. Migrance (23):72–93

Lobbé Q (2018) Revealing historical events out of web archives. In: International Conference on Theory and Practice of Digital Libraries. Springer, pp. 312–316

Lobbé Q, Delanoë A, Chavalarias D (2021) Exploring, browsing and interacting with multi-scale structures of knowledge. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03181233

Lobbe Q (2018) Archives, fragments Web et diasporas: pour une exploration désagrégée de corpus d’archives Web liées aux représentations en ligne des diasporas. Ph.D thesis

Lobbé Q (2018) Where the dead blogs are. In: International Conference on Asian Digital Libraries. Springer, pp. 112–123

Lorenzana JA (2016) Mediated recognition: the role of facebook in identity and social formations of filipino transnationals in indian cities. New Media Soc 18:2189–2206

Macias L (2019) Digital humanitarianism in a refugee camp. In: The SAGE Handbook of Media and Migration. SAGE publications, p. 334

Madianou M (2019) Technocolonialism: digital innovation and data practices in the humanitarian response to refugee crises. Soc Med Soc 5:2056305119863146

Moreno JL (1934)Nervous and mental disease monograph series, no 58.Who shall survive?: A new approach to the problem of humaninterrelations. Nervous and Mental Disease Publishing Co. https://doi.org/10.1037/10648-000

Morozov E (2013) To save everything, click here: The folly of technological solutionism. Public Affairs

Musiani F, Paloque-Bergès C, Schafer V, Thierry B (2019) Qu’est-ce qu’une archive du Web? OpenEdition Press

Pathirage J, Collyer M (2011) Capitalizing social networks: Sri lankan migration to italy. Ethnography 12:315–333

Pisarevskaya A, Levy N, Scholten P, Jansen J (2020) Mapping migration studies: an empirical analysis of the coming of age of a research field. Migration Stud 8:455–481

Ponzanesi S (2020) Digital diasporas: postcoloniality, media and affect. Interventions 0:1–17

Porter A, Rafols I (2009) Is science becoming more interdisciplinary? measuring and mapping six research fields over time. Scientometrics 81:719–745

Risam R (2018) New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy. Northwestern University Press

Rohde M, Aal K, Misaki K, Randall D, Weibert A, Wulf V (2016) Out of syria: mobile media in use at the time of civil war. Int J Human-Comput Interact 32:515–531

Sayad A (1985) Du message oral au message sur cassette, la communication avec l’absent. ISSN 0335-5322. https://doi.org/10.3406/arss.1985.2271. URL https://www.persee.fr/doc/arss_0335-5322_1985_num_59_1_2271.

Scopsi C (2009) Les sites web diasporiques: un nouveau genre médiatique? tic&société 3(1–2)

Shakhsari S (2011) Weblogistan goes to war: representational practices, gendered soldiers and neoliberal entrepreneurship in diaspora. Feminist Rev 99:6–24

Siapera E (2019) Organised and ambient digital racism: multidirectional flows in the irish digital sphere. Open Libraryof Humanities 5(1)

Theraulaz G, Bonabeau E (1999) A brief history of stigmergy. Arti Life 5:97–116

Thomas EF, Smith LGE, McGarty C, Reese G, Kende A, Bliuc A-M, Curtin N, Spears R (2019) When and how social movements mobilize action within and across nations to promote solidarity with refugees. Eur J Soc Psychol 49:213–229

Tukey JW (1977) Exploratory data analysis, vol. 2. Reading, MA

Tyner JA, Kuhlke O (2000) Pan-national identities: representations of the philippine diaspora on the world wide web. Asia Pacific Viewpoint 41:231–252

Van den Bos M, Nell L (2006) Territorial bounds to virtual space: transnational online and offline networks of iranian and turkish-kurdish immigrants in the netherlands. Glob Network 6:201–220

Zhang P (2013) Social inclusion or exclusion? when weibo (microblogging) meets the new generation of rural migrant workers, Library Trends, vol. 62, no. 1, pp. 63

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the dlWeb team of the National Audiovisual Institute (INA), to the researchers and engineers involved in the making of the e-Diasporas Atlas and in particular to Dana Diminescu.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lobbé, Q. Multi-scale methods for reconstructing collective shapes of digital diasporas. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 150 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00828-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00828-4