Abstract

Societies are increasingly multicultural and diverse, consisting of members who migrated from various other countries. However, immigrants and ethnic minorities often face discrimination in the form of fewer opportunities for labor and housing, as well as limitations on interactions in other social domains. Using mock email accounts with typical native-sounding and foreign-sounding names, we contacted 23,020 amateur football clubs in 22 European countries, asking to participate in a training session. Response rates differed across countries and were, on average, about 10% lower for foreign-sounding names. The present field experiment reveals discrimination against ethnic minority groups, uncovering organizational deficiencies in a system trusted to foster social interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All contemporary societies host different cultural and ethnic groups in their population. Increasingly diverse societies, however, do not necessarily become more tolerant of diversity. Social science research examines the behavior of individual members (Berry and Sam, 2014) and identifies ethnic and racial discrimination through field experiments in several social domains (Gaddis, 2018; Harrison and List, 2004).

Finding a job, renting an apartment, and using the sharing economy are examples of activities where discrimination is not usually directly observable. However, using fictitious applications that differ only in specific factors (e.g., ethnicity, gender, or race), research shows that minority groups face a disadvantage when accessing labor (Baert, 2018; Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004; Kaas and Manger, 2012; Lancee et al., 2019; Midtbøen, 2016; Pager et al., 2009; Quillian et al., 2017; Zschirnt and Ruedin, 2016), housing (Auspurg et al., 2019; Diehl et al., 2013; Flage, 2018), transportation (Ge et al., 2016, Liebe and Beyer, 2020), politics (Gell-Redman et al., 2018), and the sharing economy (Edelman et al., 2017; Tjaden et al., 2018).

Discrimination is traceable across occupations, regions, and countries, and is present in a range of daily activities. Although most discrimination studies focus on social domains with economic impact (e.g., labor, housing), evidence of ethnic and racial discrimination also exists in online dating (Jakobsson and Lindholm, 2014; Potârcă and Mills, 2015), shopping (Bourabain and Verhaeghe, 2019), and sport participation (Nesseler et al., 2019).

The negative implications of discrimination in social activities rely on Granovetter’s (1973) seminal idea of the strength of weak ties. The connections and personal relationships acquired in relaxed and friendly environments may result in broader social networks that act as sources of employment (McQuaid and Lindsay, 2005), housing (van Eijk, 2010), health (Szreter and Woolcock, 2004), and socioeconomic status (Campbell et al., 1986).

Participation in social activities can provide meaningful interactions, but it requires reciprocity—a willingness of foreign members to join activities and a willingness of native members to grant access (Laurentsyeva and Venturini, 2017; Ward et al., 2001). Research quantifying daily interactions between groups frequently relies on self-report measures such as number of mutual visits (Avitabile et al., 2013) or club membership (Hainmueller et al., 2017), but such measures tend to overlook the actions of native members. Alternative measures such as ethnic geographic clustering (Constant et al., 2013) and smartphone usage (Dissing et al., 2018) suffer from similar limitations.

To focus on the actions of native members and measure ethnic discrimination, in this study we use a field experiment approach. Field experiments avoid the drawbacks of self-report measures (e.g., social desirability bias; Hofmann et al., 2005) and secondary data (e.g., omitted variable bias; Blank et al., 2004). Additionally, the method eliminates the influence of external factors such as appearance, attitude, and accent (Bertrand and Mullainathan, 2004). Accordingly, using mock email accounts with native-sounding and foreign-sounding names, we contacted amateur football (soccer) clubs in 22 European countries.

Amateur sports are supposedly an integration tool that enables social interactions between individuals with different ethnic backgrounds (Council of the European Union, 2010, 2020; Duarte et al., 2012; Elling et al., 2001; Walseth, 2008). The literature on sport participation, however, shows that ethnic minorities are less likely to participate in sports than their majority counterparts (van Haaften, 2019).

This underrepresentation is usually explained as a preference of ethnic minorities for more familiar activities and relationships with peers from their own communities (Elling and Knoppers, 2005; Peucker and Ceylan, 2017). Researchers have nonetheless called attention to discriminatory actions within the club-organized sport system (Collins, 2014). The typical use of qualitative methods and case studies prevent this research from disentangling practices of exclusion from ethnic preferences (van Haaften, 2019).

To anticipate our results, individuals with foreign-sounding names received disproportionately fewer responses from amateur football clubs (e.g., in England, “Jan” did worse than “John”). The findings redirect attention from self-segregation to collective exclusion mechanisms in daily interactions of ethnic minorities (Boustan, 2013, Crozier and Davies, 2008; Peucker and Ceylan, 2017), especially in sports (van Haaften, 2019). Amateur football may offer excellent opportunities for integration (UEFA, 2020), but we find that the system is not equally accessible to everyone.

The amateur football system operates similarly in most European countries. It is based on a network of self-organized clubs within overarching (regional) federations that organize competitions (Bottenburg et al., 2005). As the organizational structure lacks a regulated process of player admission, the task of inviting a new player normally falls to coaches, players, and other staff members.

The rules of football are universal and equally, apply to all participants. Therefore, prejudices based on ethnic, racial, or religious characteristics should be of little importance, as they cannot impact the outcome of a match. Amateur football also has the advantage of not being driven by economic interests (unlike professional sports), and in most cases, there are no limits to foreign participation.

The multi-country field experiment provides a detailed picture of discrimination in Europe, but the design does not permit a more refined analysis of the mechanisms that play a role in ethnic discrimination, mechanisms such as cultural distance (Hofstede, 2001; Schwartz, 2006; Welzel, 2013), national hierarchies (Elliker, 2012; Hobson and Sharman, 2005; Juhasz and Mey, 2013), and religion (Di Stasio et al., 2021). Nevertheless, the results from this study establish a solid foundation for future research and for individual and collective action.

Data

Experimental setup

We identified 25 countries that potentially had enough amateur football clubs for empirical analysis. We excluded countries that potentially did not have enough observations (e.g., Iceland, Luxembourg, and Slovakia). Additionally, we had to exclude Bosnia and Herzegovina, Ukraine, and Belarus due to insufficient data. Ultimately, 22 countries were selected: Austria (n = 1,840), Belgium (n = 663), Croatia (n = 447), Czech Republic (n = 1,598), Denmark (n = 1,135), England (n = 1,527), Finland (n = 536), France (n = 1,847), Germany (n = 1,681), Greece (n = 437), Hungary (n = 345), Ireland (n = 308), Italy (n = 1,463), Norway (n = 999), Poland (n = 1,312), Portugal (n = 791), Romania (n = 493), Russia (n = 1,143), Serbia (n = 383), Spain (n = 1,410), Sweden (n = 1,493), and the Netherlands (n = 715).

We gathered data only for amateur leagues. The goal was to start with the lowest-level league and continue to the second-lowest league and so forth until 1,500 observations had been made for each country. However, several countries have a limited number of amateur football clubs, and we could not reach the intended number. To account for the different number of observations across countries, we cluster all regression analyses at the country level. The results are consistent when clustering for ethnicities, which is also reasonable. Figure 1 shows the geographic location of the clubs included in the experiment.

For each of the 23,020 clubs, we identified the contact email address, normally the main coach or the responsible administrator. We made sure to contact each club only once (in <0.01% of the cases, clubs were incorrectly contacted twice; we deleted these observations from the sample). We refrained from contacting a single respondent several times, as we expected that respondents would modify their behavior (Sedgwick and Greenwood, 2015).

In a few countries, some clubs also use social media networks (e.g., Facebook or VK in Russia) to receive applications. We chose not to contact clubs that work exclusively with social networks for two reasons. First, we followed the guidelines of the ethical commission of the University of Zurich and refrained from creating fictitious friends. A profile with no friends is unconventional, suspicious, and, therefore, likely to bias the results of the experiment. Second, we discovered that some of these clubs use their social network pages exclusively to communicate with players who are already members and do not allow inquiries.

Method

The first step was to generate names for each group in each country: five native-sounding names and six foreign-sounding names (two names for each foreign group, representing each of the three largest foreign groups in the respective country). Table A1 in the Supplementary Information gives a complete list of names and their respective response rate. We chose the largest foreign groups as they represent the largest share of the population. Discrimination against ethnic minority groups that represent a sizable part of the population is a threat for diverse societies.

We defined “foreign” as having another citizenship than the respective country. We split Belgium into French-speaking clubs and Dutch-speaking clubs to provide a more extensive perspective (see Table A3). As in Bertrand and Mullainathan (2004), we checked the distinctiveness of the names by conducting surveys in various public areas in the respective countries, asking respondents to categorize the names as either foreign or native. In most cases, respondents successfully categorized the names.

In very few countries, however, respondents were not able to distinguish between a native-sounding name and a foreign-sounding name from one of the three largest groups. German-sounding names in Austria, Swedish-sounding names in Norway, and Ecuadorian-sounding and Colombian-sounding names in Spain are examples. In these countries, we replaced the foreign groups whose names could not be successfully identified with the next largest foreign group in the respective country. Table A1 provides the full list of countries as well as included and excluded foreign groups.

We used block randomization by the state for each country to contact clubs (Gerber and Green, 2008). We assigned one name to every club and assigned names for natives and foreigners equally often. Using a random number generator, we created 330 seven-digit gmail.com accounts. In some cases, once the analysis was finished for a given country, we changed the name of the alias and used the same account for another country.

When the clubs were contacted, emails expressed interest only in joining a trial training session. As in previous research, no further details were provided regarding the place of residence, education, or any other attribute (Nesseler et al., 2019). The recipient could see the name twice: in the inbox and below the body of the message. The language of the email coincided with the language of the homepage of the club. The language department of the University of Zurich provided us with expert translations for every country. SM 1 in the Supplementary Information shows the full list of translated emails in the original language. In English, the email read as follows:

Subject: Trial practice

Hello,

I would like to take part in a trial training session with your team. I have already played at a similar level. Could I come for a trial training session?

Many thanks,

Name

After sending the emails, we checked every account daily in the first week and at least twice a week in the following 3 weeks. After 4 weeks, we stopped checking. Most of the responses were received after 1 or 2 days.

Responses were answered promptly. The fictitious player told the respondent that he was no longer interested and thanked the club for their response. We sent 23,020 emails in 22 countries. The total number of responses was 10,215 (5,729 for native-sounding names; 4,486 for foreign-sounding names). Native-sounding names generated 1,988 requests for more information; foreign-sounding names generated 1,459.

Following prior research (Nesseler et al., 2019), we categorized responses as (1) no response or rejection; (2) positive response (i.e., an invitation to a practice session); and (3) positive response with further inquiries (i.e., an invitation with additional questions; typical questions concerned the position, age, and previous playing experience of the applicant). We did not distinguish between rejections and no responses because only a small percentage of the responses were outright rejections. To analyze the results, we combined positive responses and positive responses with additional inquiries into one group; thus a binary variable was constructed that distinguished between a positive and a negative response. We also analyzed whether one’s name has an impact on the type of positive response (categories 2 and 3 above), but no significant differences were found. Figure A1 and Table A2 (Supplementary Information) show the positive response results.

Results

Responses

The overall response rate was roughly 44%. The pooled results from all countries show that foreign-sounding names received significantly fewer responses than native-sounding names (0.495 vs. 0.391; average treatment effect (ATE) 0.102; Mann–Whitney U, z = −15.92, P = 0.00, n = 23,020). We did not find differences between the first-, second-, and third-largest groups with foreign-sounding names (0.403 vs. 0.388 vs. 0.383; Kruskal–Wallis H, χ = 2.52, P = 0.28, n = 11,462).

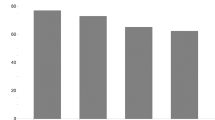

Figure 2 shows the response rate for native-sounding names (yellow bar) and foreign-sounding names (blue bar) for each country. The response rate clearly differed between countries. The Netherlands had the highest response rate (all = 69.4%, foreign = 64.5%, native = 74.3%), while Serbia had the lowest (all = 12.0%, foreign = 9.3%, native = 15.1%). Notice that for every country, the response rate was lower for foreign-sounding names.

As in debates about poverty, it is important to look not only at the absolute response rate but also the relative rate (Sen, 1983). Table 1 reports the statistical significance of the difference in response rates between native- and foreign-sounding names for every country. Table A3 (Supplementary Information) shows the regression results for the three different foreign-sounding groups in every country.

The results again show differences between countries. Ireland, France, and Portugal have the lowest differences (below 4%), whereas Croatia, Hungary, and Austria have the highest differences (above 20%). For most of the remaining countries, the response rate difference is between 5% and 13%. Figure 3 ranks the difference in response rates between foreign-sounding and native-sounding names by country. The results are shown with a 95% confidence level bar.

In a randomized field experiment, the results should not be influenced by other factors (Gerber and Green, 2008). To control for the validity of the experiment and to understand how potential factors may have influenced response rate, we included net migration (M = 2.36, SD = 5.94, n = 20,955) and the size of the population living in the local district (M = 743,171, SD = 1,571,799, n = 20,955). To improve the readability of the tables, we divided the population by 100,000. We used the smallest district level that was available (viz., Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics 3). However, for several clubs, these data were not traceable. Additionally, we included a control for the league, as clubs from lower-level leagues might have a different willingness to respond.

Thus, we ran three ordinary least-square regressions with robust standard errors clustered at the country level: (1) without covariates for the complete sample, (2) without covariates for the limited sample, and (3) with covariates for the limited sample. Table 2 reports the results. In all three models, foreign-sounding names received approximately 10–11% fewer responses.

Similar to previous findings for Europe on diversity and generalized trust (Hooghe et al., 2009), net migration has a positive influence on the response rate. Population size has no significant influence. Additionally, we analyzed if aggregated data influences the results. For this, we focus on two indices: (1) the Migrant Integration Policy Index score (mipex), which measures policies to integrate migrants; (2) the cultural rights variable from the Indicators of Citizenship Rights for Immigrants. Both indices have a statistically significant influence, but they do not influence response rate. The results are available in the Supplementary Information (Table A4).

Discussion

The results of this study show that individuals with foreign-sounding names face a barrier to participation in amateur football in Europe. This evidence of discrimination challenges the notion of equal access in sport regardless of ability, race, or gender (UEFA, 2020), and contributes to the debate concerning collective exclusion vs. self-segregation in social participation of ethnic minorities (Crozier and Davies, 2008; Peucker and Ceylan, 2017; Phillips, 2010; van Haaften, 2019).

While cultural preferences may still play a role in the complex process of integration and sport participation (Elling and Knoppers, 2005), we find evidence of ethnic discrimination in European amateur football. The field experiment approach extends previous qualitative efforts to understand collective exclusion mechanisms in sports (Collins, 2014; van Haaften, 2019).

Ethnic discrimination in sports is a threat for employment, education, and related opportunities in local communities in Europe (UEFA, 2020), limiting the potential of individuals to create other ties and social networks (Granovetter, 1973). Barriers to participation in social activities prevent ethnic minorities from achieving successful integration in their host countries, including political and economic mobility (Hainmueller et al., 2017).

Evidence of ethnic discrimination in sports aligns with traditional theories of social identity and in-group preferences (Byrne, 1971; Tajfel, 1982), and extends previous findings in the labor and housing markets of European countries, including Denmark (Hjarnø and Jensen, 2008), Finland (Öblom and Antfolk, 2017), France (Duguet et al., 2010), Germany (Diehl et al., 2013; Kaas and Manger, 2012), Greece (Drydakis and Vlassis, 2010), Ireland (Gusciute et al., 2020; McGinnity and Lunn, 2011), the Netherlands (Andriessen et al., 2012), Norway (Midtbøen, 2016), Spain (Bosch et al., 2010), and Sweden (Bursell, 2014), among others.

In the countries used in this study, the results show a lower number of responses to foreign-sounding names. We do not find, however, geographical patterns. Response rate differences between native- and foreign-sounding names are not clustered in culturally similar regions (e.g., Scandinavia or Eastern Europe) or in regions with a similar percentage of foreign inhabitants (e.g., Romania and Italy have a very different share of foreign-born citizens but similar response rates). The idiosyncrasies of the names and perceptions of the largest foreign groups in each country may influence the results.

In today’s diverse societies, name discrimination affects not only individuals from foreign groups but also naturalized immigrants and their descendants. In some cases, foreign-sounding names could be the names of second- or third-generation migrants (e.g., Turkish-sounding names in Germany or Algerian-sounding names in France). However, the present experiment was not designed to investigate detailed differences across names and nationalities.

In the experimental design, we used six names representing three different nationalities (two names for each nationality) to build the foreign groups in the respective countries. Greater variability among foreign-sounding names would be more informative and would improve representability. While responses across names vary considerably in some countries (e.g., Irish-sounding names in Ireland or Italian-sounding names in Croatia), they do so only marginally in others (see e.g., Norwegian-sounding names in Norway or Polish-sounding names in Denmark).

The composition of foreign groups with nationalities that represent a sizable part of the population in the respective countries but differ in historical representation, cultural distance, or size also has limitations. Well-established ethnic minority groups are not distinguished from other historically less represented ethnic minority groups in the analyzed countries. This is the case, for example, for Indian- and Polish-sounding names in the UK and Algerian-sounding and Portuguese-sounding names in France. Future research could focus on well-established and known ethnic minority groups to analyze discrimination in sports and other social activities.

Differences in customs and cultural values also play a role in ethnic discrimination (Hofstede, 2001; Schwartz, 2006; Welzel, 2013) and may influence the number of responses. In our results, we do not always observe the influence of cultural proximity. For example, the cultural distance of individuals with Iraqi-sounding and Polish-sounding names is different in Sweden, but the number of responses is similar. Positive discrimination toward individuals with foreign-sounding names from strong football countries is also a possibility. However, this positive discrimination would be based on subjective and dynamic perceptions, which are difficult to trace in the multi-country experiment. Future research could use these perceptions to understand the hierarchy of nationalities and measure positive discrimination in specific social contexts.

The size of the foreign group is another macro perspective that cannot explain the number of responses. While in some countries the largest foreign group received the fewest number of responses (e.g., Denmark), in other countries it is the second-largest (e.g., Germany), or third-largest foreign group (e.g., Croatia). The different number of football clubs in the samples (from 308 clubs in Ireland to 1847 clubs in France) should be considered when making comparisons. The deviations between names vary as the number of emails sent from an account differs per country.

The cross-national experiment is also bound to neglect the potential intersections of nationality and ethnicity with religion, race, and perceived status. Future studies may focus on these intersections in selected countries and attempt to disentangle the moderating factors. The design allows for several modifications and establishes the grounds for interdisciplinary research. Beyond the nationalities that compose the foreign groups, the level of education, language skills, and previous experience of applicants can easily be altered by modifying the content of the email.

Future studies should focus on demographic groups, which are missing in our experiment. The limited number of female clubs in Europe did not allow us to analyze the influence of gender. However, a few countries are suited to extend this line of research (e.g., the Netherlands, Germany, and Sweden). Moreover, amateur football is a popular social activity but directed to a certain age group, which excludes older adults. Future research may consider examining other sport disciplines as well as social activities (e.g., choral singing) with deeply rooted domestic traditions.

Raising awareness is important to reduce biases against minority groups (Pope et al., 2018), but research should examine the influence of additional factors; for example, slight modifications in individual behavior such as being persistent (Dietl et al., 2020). Information nudges—effective in improving the access of minority groups to social benefits (Hotard et al., 2019)—may be a feasible way to reduce ethnic discrimination in amateur sports.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study is publicly available in HarvardDataVerse, https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/FOXODW. Due to the conditions of the ethics committee of the University of Zurich, we deleted all information that identified clubs’ individual responses. A list of all names, foreign groups, and the emails in their original language are given in the Supplementary Information.

References

Andriessen I, Nievers E, Dagevos J, Faulk L (2012) Ethnic discrimination in the Dutch labor market: its relationship with job characteristics and multiple group membership. Work Occup 39:237–269

Auspurg K, Schneck A, Hinz T (2019) Closed doors everywhere? A meta-analysis of field experiments on ethnic discrimination in rental housing markets. J Ethn Migr Stud 45:95–114

Avitabile C, Clots-Figueras I, Masella P (2013) The effect of Birthright citizenship on parental integration outcomes. J Law Econ 56:777–810

Baert S (2018). Hiring discrimination: An overview of (almost) all correspondence experiments since 2005. In: Gaddis SM (ed) Audit studies: behind the scenes with theory, method, and nuance. Springer, pp. 63–77

Berry JW, Sam DL (2014) Multicultural societies. In: Benet-Martínez V, Hong Y (eds) The Oxford handbook of multicultural identity. Oxford University Press, 97–117

Bertrand M, Mullainathan S (2004) Are Emily and Greg more employable than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination. Am Econ Rev 94:991–1013

Blank RM, Dabady M, Citro CF (2004) Measuring racial discrimination. National Academies Press

Bosch M, Carnero MA, Farre L (2010) Information and discrimination in the rental housing market: evidence from a field experiment. Reg Sci Urban Econ 40:11–19

Bottenburg MV, Rijnen B, Sterkenburg J (2005). Sports participation in the European Union: trends and differences. Arko Sports Media

Bourabain D, Verhaeghe PP (2019) Could you help me, please? Intersectional field experiments on everyday discrimination in clothing stores. J Ethn Migr Stud 45:2026–2044

Boustan LP (2013) Racial residential segregation in American cities. Working Paper w19045. National Bureau of Economic Research

Bursell M (2014) The multiple burdens of foreign-named men—evidence from a field experiment on gendered ethnic hiring discrimination in Sweden. Eur Sociol Rev 30:399–409

Byrne D (1971) The attraction paradigm. Academic Press

Campbell KE, Marsden PV, Hurlbert JS (1986) Social resources and socioeconomic status. Soc. Netw 8:97–117

Collins MF (2014) Sport and social exclusion. Routledge

Constant AF, Schüller S, Zimmermann KF (2013). Ethnic spatial dispersion and immigrant identity. IZA discussion papers, No. 7868. Institute for the Study of Labor

Council of the European Union (2020). Compass: Manual for Human Rights Education with Young people. Culture and Sport. Council of the European Union

Council of the European Union (2010). Council conclusions of 18 November 2010 on the role of sport as a source of and a driver for active social inclusion. Council of the European Union

Crozier G, Davies J (2008) “The trouble is they don’t mix”: self‐segregation or enforced exclusion? Race Ethn. Educ 11:285–301

Di Stasio V, Lancee B, Veit S, Yemane R (2021) Muslim by default or religious discrimination? Results from a cross-national field experiment on hiring discrimination. J Ethn Migr Stud 47:1305–1326

Diehl C, Andorfer VA, Khoudja Y, Krause K (2013) Not in my kitchen? Ethnic discrimination and discrimination intentions in shared housing among university students in Germany. J Ethn Migr Stud 39:1679–1697

Dietl H, Gomez-Gonzalez C, Moretti P, Nesseler C (2020). Does persistence pay off? Accessing social activities with a foreign-sounding name. Appl Econ Lett 1–5 (in press)

Dissing AS, Lakon CM, Gerds TA, Rod NH, Lund R (2018) Measuring social integration and tie strength with smartphone and survey data. PLoS ONE 13:1–14

Drydakis N, Vlassis M (2010) Ethnic discrimination in the Greek labour market: Occupational access, insurance coverage and wage offers. Manchester Sch 78:201–218

Duarte R, Araújo D, Correia V, Davids K (2012) Sports teams as superorganisms. Sports Med 42:633–642

Duguet E, Leandri N, L’Horty Y, Petit P (2010) Are young French jobseekers of ethnic immigrant origin discriminated against? A controlled experiment in the Paris area. Ann Econ Stat 99:187–215

Edelman B, Luca M, Svirsky D (2017) Racial discrimination in the sharing economy: evidence from a field experiment. Am Econ J Appl Econ 9:1–22

Elliker F (2012) Demokratie in Grenzen. Springer-Verlag

Elling A, Knoppers A (2005) Sport, gender and ethnicity: practises of symbolic inclusion/exclusion. J Youth Adolesc 34:257–268

Elling A, De Knop P, Knoppers A (2001) The social integrative meaning of sport: a critical and comparative analysis of policy and practice in the Netherlands. Sociol Sport J 18:414–434

Flage A (2018) Ethnic and gender discrimination in the rental housing market: evidence from a meta-analysis of correspondence tests, 2006–2017. J Hous Econ 41:251–273

Gaddis SM (2018) Audit studies: behind the scenes with theory, method, and nuance. Springer

Ge Y, Knittel CR, MacKenzie D, Zoepf S (2016) Racial and Gender Discrimination in Transportation Network Companies. Working Paper w22776. National Bureau of Economic Research

Gell-Redman M, Visalvanich N, Crabtree C, Fariss CJ (2018) It’s all about race: how state legislators respond to immigrant constituents. Polit Res Q 71:517–531

Gerber A, Green DP (2008) Field experiments and natural experiments. In: Box-Steffensmeier JM, Brady HE, Collier D (eds) The Oxford handbook of political methodology. Oxford University Press, pp. 357–381

Granovetter MS (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78:1360–1380

Gusciute E, Mühlau P, Layte R (2020) Discrimination in the rental housing market: a field experiment in Ireland. J Ethn Migr Stud 1–22 (in press)

Hainmueller J, Hangartner D, Pietrantuono G (2017) Catalyst or crown: does naturalization promote the long-term social integration of immigrants? Am Polit Sci Rev 111:256–276

Harrison GW, List JA (2004) Field experiments. J Econ Lit 42:1009–1055

Hjarnø J, Jensen T (2008) Discrimination in employment against immigrants in denmark: a situation testing survey. International Labour Office

Hobson JM, Sharman JC (2005) The enduring place of hierarchy in world politics: Tracing the social logics of hierarchy and political change. Eur J Int Relat 11:63–98

Hofmann W, Gawronski B, Gschwendner T, Le H, Schmitt M (2005) A meta-analysis on the correlation between the implicit association test and explicit self-report measures. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 31:1369–1385

Hofstede G (2001) Culture’s consequences: comparing values, behaviors, institutions and organizations across nations. Sage

Hooghe M, Reeskens T, Stolle D, Trappers A (2009) Ethnic diversity and generalized trust in Europe: a cross-national multilevel study. Comp Polit Stud 42:198–223

Hotard M, Lawrence D, Laitin DD, Hainmueller J (2019) A low-cost information nudge increases citizenship application rates among low-income immigrants. Nat Hum Behav 3:678–683

Jakobsson N, Lindholm H (2014) Ethnic preferences in internet dating: a field experiment. Marriage Fam Rev 50:307–317

Juhasz A, Mey E (2013) Die Zweite Generation: Etablierte oder Außenseiter? Biographien von Jugendlichen Ausländischer Herkunft. Springer-Verla

Kaas L, Manger C (2012) Ethnic discrimination in Germany’s labour market: a field experiment. Ger Econ Rev 13:1–20

Lancee B et al. (2019) The GEMM Study: a cross-national harmonized field experiment on labour market discrimination. Technical Report. Retrieved from: http://gemm2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/GEMM-WP3-technical-report.pdf

Laurentsyeva N, Venturini A (2017) The social integration of immigrants and the role of policy—a literature review. Intereconomics 52:285–292

Liebe U, Beyer H (2020) Examining discrimination in everyday life: a stated choice experiment on racism in the sharing economy. J Ethn Migr Stud 1–24 (in press)

McGinnity F, Lunn PD (2011) Measuring discrimination facing ethnic minority job applicants: an Irish experiment. Work Employ Soc 25:693–708

McQuaid RW, Lindsay C (2005) The concept of employability. Urban Stud 42:197–219

Midtbøen AH (2016) Discrimination of the second generation: evidence from a field experiment in Norway. J Int Migr Integr 17:253–272

Nesseler C, Gomez-Gonzalez C, Dietl H (2019) What’s in a name? Measuring access to social activities with a field experiment. Palgrave Commun 5:1–12

Öblom A, Antfolk J (2017) Ethnic and gender discrimination in the private rental housing market in Finland: a field experiment. PLoS ONE 12:1–14

Pager D, Western B, Bonikowski B (2009) Discrimination in a low-wage labor market: a field experiment. Am Sociol Rev 74:777–799

Peucker M, Ceylan R (2017) Muslim community organizations—sites of active citizenship or self-segregation? Ethn Racial Stud 40:2405–2425

Phillips D (2010) Minority ethnic segregation, integration and citizenship: a European perspective. J Ethn Migr Stud 36:209–225

Pope DG, Price J, Wolfers J (2018) Awareness reduces racial bias. Manag Sci 64:4988–4995

Potârcă G, Mills M (2015) Racial preferences in online dating across European countries. Eur Sociol Rev 31:326–341

Quillian L, Pager D, Hexel O, Midtbøen AH (2017) Meta-analysis of field experiments shows no change in racial discrimination in hiring over time. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114:10870–10875

Schwartz SH (2006) A theory of cultural value orientations: explication and applications. Comp Sociol 5:137–182

Sedgwick P, Greenwood N (2015) Understanding the Hawthorne effect. BMJ 351:1–2

Sen APoor (1983) relatively speaking. Oxf Econ Pap 35:153–169

Szreter S, Woolcock M (2004) Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol 33:650–667

Tajfel H (1982) Social psychology of intergroup relations. Annu Rev Psychol 33:1–39

Tjaden JD, Schwemmer C, Khadjavi M (2018) Ride with me—ethnic discrimination, social markets, and the sharing economy. Eur Sociol Rev 34:418–432

UEFA (2020) Explainer: valuing European football’s social return on investment. https://www.uefa.com/insideuefa/football-development

van Eijk G (2010) Unequal networks: spatial segregation, relationships and inequality in the city, vol 32. IOS Press VB

van Haaften AF (2019) Ethnic participation in Dutch amateur football clubs. Eur J Sport Soc 16:301–322

Walseth K (2008) Bridging and bonding social capital in sport—experiences of young women with an immigrant background. Sport Educ Soc 13:1–7

Ward CA, Bochner S, Furnham A (2001) The psychology of culture shock. Routledge

Welzel C (2013) Freedom rising. Cambridge University Press

Zschirnt E, Ruedin D (2016) Ethnic discrimination in hiring decisions: a meta-analysis of correspondence tests 1990–2015. J Ethn Migr Stud 42:1115–1134

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF), grant no. CRSK-1_190264 and Stiftung für wissenschaftliche Forschung an der Universität Zürich. For assisting us in preparing the field experiment, we would like to thank Evgeny Alexandrov, Louridas Alkivadis, Georgina Alvarez Morera, Gayane Bagumyan, Davor Beganović, Elisabeth Berg, Gregory Boadu-Sebbe, Dumitru Chihaï, Lusine Davtyan, Katalin Demko, Jelena Gall, Malgorzata Gerber, Markus Giger, Giovanni Giulardi, Jonathan Götting, Maria Hannus, Annika Harju, Michèle Hegi, Natasa Hemon, Johannes Kabatek, Alva Liljeroth, Pascal Lippuner, Anna Möhl, Teresa Romero, Anna Schaffner, Louis Schick, Josef Simpartl, Caroline Sørensen, Nataliia Strukova, and Ivan Trestcov.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this study and share the responsibility for its content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gomez-Gonzalez, C., Nesseler, C. & Dietl, H.M. Mapping discrimination in Europe through a field experiment in amateur sport. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 95 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00773-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00773-2