Abstract

Aging societies are one of the major problems faced in the modern world. Promoting subjective wellbeing is a key component in helping individuals positively accept and adapt to psychological and physical changes during their aging process. Tourism is one of the activities that have been demonstrated to promote subjective wellbeing. However, motivation for tourism and its benefits to subjective wellbeing among the older adults have rarely been discussed. The current study aimed to investigate whether tourism contributes to the subjective wellbeing of older adults. We examined the relationships between travel frequency, subjective wellbeing, and the personal trait of curiosity, mediated by the factor of family budget situation. The results demonstrated that diverse curiosity motivates individuals to travel; thus, diverse curiosity positively correlates to subjective wellbeing, both directly as well as indirectly through travel frequency. However, this relationship is limited by the factor of family budget, with tourism contributing to the subjective wellbeing of only well-off older adults. This study concludes that tourism has potential to contribute to subjective wellbeing during later stages of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals’ perspectives on aging may be somewhat negative due to issues such as increasing disease morbidity and declining productivity and cognitive function. In today’s aging societies, a great deal of attention has thus been devoted to the positive acceptance of aging, which involves a focus on adapting to and enjoying the older stages of life despite inevitable psychological and physical changes.

Quality of life is one of the indicators of acceptance of aging. Quality of life positively correlates with psychological acceptance, which is the willingness to accept age-related changes and distress (Butler and Ciarrochi, 2007). Subjective wellbeing, which is a self-reported measure of a person’s wellbeing that includes global assessment of several aspects of life, captures individual evaluation of quality of life (Diener, 1984). Furthermore, positive affect is reported to play a protective role against the development of dementia among older adults (Murata et al., 2016). Thus, promoting subjective wellbeing among older adults, especially in the early stages of old age, may lead to improved perspectives on aging and maintaining cognitive health while aging.

Exposures to various life conditions and activities are reported to be associated with subjective wellbeing, and tourism is one activity that has been suggested to be linked to the quality of life of older adults (Zhang and Zhang, 2018; Kim et al., 2015). Tourism is suggested to positively affect multiple life domains of the tourist, and it is suggested that travels generally contribute to positive affect and quality of life (Uysal et al., 2016). However, it has not been investigated whether more frequent travel contributes to higher subjective wellbeing.

Personality traits provide important motives that lead individuals to travel. It has been suggested that leisure time activity preference, including for tourism, is predetermined by personal disposition (Przepiorka and Blachnio, 2017; Diener et al., 1999; Lee and Crompton, 1992). Moreover, perception of subjective wellbeing is also suggested to have a strong relationship to personality (Steel et al., 2008). This relationship is based on the fact that personality affects preference for involvement in activities (Przepiorka and Blachnio, 2017; Diener et al., 1999) and that specific personalities evaluate the meaning of life events more positively than others.

Curiosity is one personal characteristic that motivates individuals to devote time to leisure activities and also correlates to subjective wellbeing (Nishikawa et al., 2015; Nishikawa, 2014). Besides the common recognition that curiosity acts as a motivation to travel, curiosity has received little attention in relation to travel motivation.

With regard to the relationship between tourism and subjective wellbeing, other internal factors, social environment, and external circumstances need to be considered, besides just personality traits. One of the factors that cannot be ignored is the state of the family budget. Satisfaction with income has been suggested to relate to happiness (Diener et al., 1993, 1999), and since tourism costs money, a certain amount of income or wealth is required to afford travelling (Fleischer and Pizam, 2002).

Given the importance of subjective wellbeing of seniors, the potential of tourism frequency to affect subjective wellbeing, and the suggested relationship of curiosity with both tourism involvement and subjective wellbeing, the current study aimed to investigate the relationships among these three factors. We hypothesized that curiosity is one of the key predictors of travelling preference and subjective wellbeing among older adults and that travel frequency positively correlates with subjective wellbeing even after controlling for trait curiosity; however, we also hypothesized that this relationship is mediated by family budget. We focused on people in their 60s, as it is thought that early intervention towards subjective wellbeing is a promising approach to maintaining cognitive health of the older adults; also, this age group is already more active in travelling than other age groups and is a most attractive age group for travel marketers.

The current study contributes to the better understanding of the contribution of tourism to subjective wellbeing among older adults by operationalizing curiosity as an underlying personal disposition. Recommendations are provided for the travel industry, to help promote subjective wellbeing among older adults.

Literature review and hypothesis development

Young seniors as a target for intervention to promote subjective wellbeing

As of September 2020, the elderly ratio (percentage of the population that is over 65 years old) has reached 28.7% in Japan. Total population in Japan has decreased by 290,000 from last year, while population over 65 years old has increased by 300,000 (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2020). One of the problems we face in the aging society is increasing morbidity due to dementia. Dementia comprises a group of symptoms associated with cognitive decline and loss of ability to perform everyday activities according to pathological changes of the brain. It is one of the major causes of elderly dependency and disability, and impacts quality of life, affecting the physical, psychological, social, and economic situation not only of the individual who develops dementia but also of their families, caregivers, and the wider society. However, late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is suggested to have a negative association with risk of dementia (Wang et al., 2002), and subjective wellbeing is also suggested to play a protective role against functional decline (Hirosaki et al., 2013) and cognitive decline (Murata et al., 2016). Therefore, intervention for subjective wellbeing especially in early seniors is expected to be promising in terms of maintaining cognitive health.

Contribution of travel to subjective wellbeing

Exposures to various life conditions and activities are reported to be associated with subjective wellbeing, and tourism is one activity that has been suggested to be linked to quality of life in older adults (Zhang and Zhang, 2018; Kim et al., 2015).

Travelling requires various cognitive activities, such as choosing a destination, arranging activities, conducting them as planned or intentionally departing from plans, communicating with one’s companions and local people, and managing possible contingencies in unfamiliar situations. Gaining such generally pleasant experiences leads to subjective wellbeing in tourists, and it has been shown that tourists also show ‘pre-trip-happiness’ while planning and anticipating travel (Gilbert and Abdullah, 2004). Tourism is suggested to positively affect the tourist’s life domains, such as leisure life, social life, family life, and cultural life, and to contribute to life satisfaction (Uysal et al., 2016).

Previous studies on the relationship between travelling and subjective wellbeing have mainly focused on detailed description of travellers: who they are, with whom they go, where they go, what they do, what aspects of their lives are influenced by the experience, and what internal mediating factors for subjective wellbeing relate to the quality of their travel. For instance, Gram et al. (2019) showed that travel with grandchildren offers both fun time and legacy time to seniors and contributes to both individual and intergenerational wellbeing. Furthermore, Fritz and Sonnentag (2006) showed that vacations offer employees experiences such as positive and negative work reflections, relaxation, mastery experience, and break from work hassles and thus improve subjective wellbeing. These studies offer a better understanding of the contribution of travel to subjective wellbeing, although in limited social and travel settings. In addition, however, holistically, Uysal et al. (2016) point out in a review that travel, in general, contributes to positive affect and quality of life. Therefore, promoting travel in any situation may promote subjective wellbeing. However, few studies have focused on the relationship between travel frequency (quantity of travel) and subjective wellbeing, and it has not been revealed whether frequent travel contributes to higher subjective wellbeing. Accordingly, the following hypothesis was developed in this study:

Hypothesis 1: Frequent travellers show better subjective wellbeing than less frequent travellers.

Young seniors as a target for tourism marketing

Older adults are an emerging target of tourism marketing in Japan nowadays. People in their 60s are among the most frequent travellers (Odaka et al., 2011; Japan Tourism Agency, 2020), as they are often financially well off and have more leisure time to spare than younger people (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2016). Also, while people over 70 exhibit a steep increase in amount of time spent on medical care, in hospital, and in recuperation (Statistics Bureau of Japan, 2016), people in their 60s are healthier and more able to travel. Promoting travel in younger age groups, who are often in the middle of their working lives, may not be easy; additionally, in Japan, these age groups are decreasing in size compared to older adults, meaning diminishing returns on pursuing them as tourists. The population in their 60s will show an absolute increasing trend and an increase in the ratio among the whole population until 2036 (National institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2017). Therefore, the 60s age group is a major target for intervention by tourism marketers to promote travel.

Motivation for travel

Travel marketers have devoted great attention to understanding the travel motivation of customers and factors influencing it. Crompton (1979) classified relevant socio-psychological motives into seven: escape from a perceived mundane environment, exploration and evaluation of self, relaxation, prestige, regression, enhancement of kinship relationships, and facilitation of social interaction; these were accompanied by two cultural motives: novelty and education. Among seniors, it has been found that rest and relaxation, social interaction, physical exercise, learning, nostalgia and excitement are common reasons for travel (Fleischer and Pizam, 2002).

Socio-psychological motives of individuals are often discussed from the standpoint of personality traits. It has been suggested that leisure time activity preference, including for tourism, is predetermined by personality (Przepiorka and Blachnio, 2017; Diener et al., 1999; Lee and Crompton, 1992). Among personality traits related to travel are allocentrism and psychocentrism; Plog (1974) has classified tourist character in terms of these. Allocentrism refers to the characteristics of outgoingness, self-confidence, and adventurousness, while psychocentrism refers to the characteristics of self-inhibition, nervousness, and non-adventurousness. These two characteristics lead to opposite preferences in travel destinations: allocentric tourists tend to prefer unexplored destinations and psychocentric tourists to prefer familiar destinations. The personal characteristic of novelty-seeking is also suggested to play a role in choosing travel destinations (Lee and Crompton, 1992).

Curiosity

Curiosity is another personal characteristic suggested to motivate travel. It refers to personal dispositions motivating individuals to obtain cognitive stimulation, that is, to desire knowledge and experience, and is consistently recognized as a critical intrinsic motivator of human behaviour (Berlyne, 1954; Litman and Spielberger, 2003; Lowenstein, 1994). Epistemic curiosity is predominant in humans, distinguishing human curiosity from that of other species (Kidd and Hayden, 2015; Berlyne, 1966). It refers to the drive not only to access information-bearing stimulation, capable of dispelling the uncertainties of the moment, as other species do, but also to acquire knowledge.

Definitions of epistemic curiosity vary between researchers; in the current study, we use the definition of Nishikawa and Amemiya (2015), in which epistemic curiosity consists of two dimensions: diverse curiosity and specific curiosity. Diverse curiosity is defined as the motivation to widely explore new information, while specific curiosity is the motivation to explore specific information in order to solve cognitive conflicts (Nishikawa and Amemiya, 2015). Nishikawa and Amemiya’s theory of epistemic curiosity has its origins in research by Hatano and Inagaki (1971) showing that those with more diverse curiosity tend to actively seek novel and varied information, while those with more specific curiosity tend to be sensitive to inconsistency and to actively and continuously seek information to cope with contradiction (Nishikawa and Amemiya, 2015; Hatano and Inagaki, 1971). Despite the fact that curiosity drives individuals to actively seek information, it has received little attention in the context of travel motivation. Accordingly, we have set the following hypothesis to investigate the relationship of curiosity to travel:

Hypothesis 2: Frequent travellers show higher epistemic curiosity than less frequent travellers.

Personal traits as determiners of subjective wellbeing

Besides the relationship of personality traits to travel motivation, existing studies have also suggested that personality traits acts as a strong determinant of subjective wellbeing (Steel et al., 2008). This relationship is based on the fact that certain personalities evaluate life experiences more positively than others. Chen and Yoon (2018) reported a relationship between tourism, wellbeing, and the personality trait of novelty-seeking, finding that the direct effect of novelty-seeking on life satisfaction (top-down influence) was significantly greater than the indirect effect through tourism experiences (bottom-up influence) (Chen and Yoon, 2018). Furthermore, curiosity is also reported to be related to subjective wellbeing via maintaining knowledge in older adults (Kashidan and Steger, 2007; Nishikawa et al., 2015). Therefore, when considering curiosity as a motivation to travel, the effect of curiosity on subjective wellbeing needs to be taken into account. Accordingly, we set the following hypotheses to investigate the causal relationship between travel frequency, subjective wellbeing, and curiosity:

Hypothesis 3: Curiosity has a positive correlation with subjective wellbeing.

Hypothesis 4: Travel frequency positively correlates with subjective wellbeing even after being controlled by trait curiosity (main hypothesis, to investigate whether travel frequency contributes to subjective wellbeing of the older adults in a relationship with curiosity).

Moderation effects of income on travel involvement and subjective wellbeing

Besides personal traits, other internal factors, social environment, and external circumstances needs to be considered as factors moderating travel involvement’s effect on subjective wellbeing. One such factor that has been discussed is the effect of income. Satisfaction with income has been suggested to relate to happiness (Diener et al., 1993, 1999), and since tourism costs money, a certain amount of income or wealth is required to afford it (Fleischer and Pizam, 2002). Therefore, we proposed the following hypothesis.

Hypothesis 5: Family budget situation alters the relationship among travel frequency, subjective wellbeing, and curiosity.

Methods

Participants

The participants were selected from a pool of Japanese customers in their 60s who were registered with a travel agency. These customers were sent a questionnaire asking about their attitudes toward travelling, daily living conditions (such as age, income, subjective family budget situation, medical status, occupation, family structure, and self-perceived health), and cognitive traits. All study participants provided informed consent, and the study design was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tohoku University (Approved No. 2018-1-740). Data were collected in June 2017, before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Of the 1068 participants who responded to and returned the questionnaire, 233 were excluded due to deficient questionnaire data. In total, 835 participants were included in the study (n = 835; male = 437, mean age = 64.73 ± 2.79).

Global self-report measures

Trait curiosity

Using a 5-point Likert scale, participants completed the 12-item Epistemic Curiosity Scale (Nishikawa and Amemiya, 2015), rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale was developed by Nishikawa and Amemiya, the same researchers who proposed the definition of epistemic curiosity used in the current study. The scale consists of 12 items, 6 each on diverse and specific curiosity. Examples of items to evaluate diverse curiosity are ‘I enjoy solving novel problems’ and ‘I am interested in things that no one has ever experienced’; in contrast, examples of items to evaluate specific curiosity are ‘I would like to investigate thoroughly when learning something’ and ‘I think carefully and devote a long time to solving problems’. The scale was developed and is presented in Japanese. (The example questionnaire items mentioned above were translated by the authors of the current study for better understanding of the scale, and are not validated in English).

Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS)

Using a 7-point Likert-type scale, participants completed the 4-item Japanese version of the SHS (Lyubomirsky and Lepper, 1999; Shimai et al., 2004), rated from 1 (not a very happy person, less happy, not at all) to 7 (a very happy person, more happy, a great deal). The SHS assesses subjective happiness from the respondent’s own perspective, including both cognitive and affective evaluation of personal life. This differs from some measurement tools for subjective wellbeing, which are biased toward either cognitive or affective aspects.

Questionnaire regarding travel frequency

Participants rated their recent frequency of travel from the following options: (1) more than 10 times per year, (2) 5–9 times per year, (3) 3–4 times per year, (4) 1–2 times per year, (5) once in 2–3 years, and (6) less than once in 2–3 years (Hardly ever). The definition of the travel was dependent on the respondents’ own perspectives. The variable of travel frequency is used as a nominal variable in the analysis to investigate hypotheses 1 and 2 and as an ordinal variable to clarify the correlation between the two components of epistemic curiosity and travel frequency in the testing of hypothesis 2 and in hypothesis 3–5.

Questionnaire regarding subjective family budget situation

Participants rated their recent subjective family budget situation from the following options: (1) Extremely good, (2) Moderately good, (3) Neither good nor bad, (4) Moderately bad, and (5) Extremely bad. In asking the financial situations of individuals, we assumed that participants may have different numbers of family members to provide for, levels of debt, cost of shelter and of living, and ideal living standards, so that their financial situation may not simply be validated by the amount of income itself. Thus, we adopted a scale asking for participants’ subjective feelings on their family budget situations. The variable was reclassified into three groups according to whether they considered their family budget situation to be (1) Extremely/moderately good, (2) Neither good nor bad, or (3) Moderately/extremely bad. The results were used in the testing of hypothesis 5.

Statistical analysis

For cognitive function, statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21 software. The mediation analyses were performed using the SPSS PROCESS macro (http://processmacro.org/index.html) (Hayes, 2018). Mediation analysis was performed with a bootstrapping approach using 10,000 resamples.

Results

Participants’ profiles

We surveyed Japanese customers aged 59–69 who had registered with a travel agency (n = 835; male = 437, mean age = 64.73 ± 2.79SD). They completed the questionnaire on their travel frequency and demographic and daily living conditions, such as age and subjective family budget situation. Participants also completed the Epistemic Curiosity Scale for the measurement of personal characteristics and the SHS for the measurement of subjective wellbeing. The participants’ demographic characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Mean age and subjective wellbeing scores were significantly higher in male participants than in female participants (t-test p < 0.001, p = 0.017). No significant difference was observed between epistemic curiosity score, travel frequency, and subjective family budget situations (Tables 1 and 2).

Relationship of travel frequency with subjective wellbeing

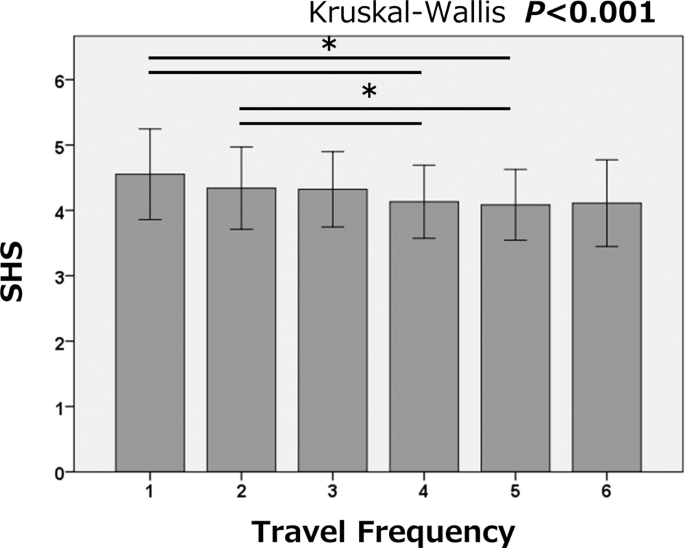

First, to investigate the positive relationship between travel and subjective wellbeing, we conducted a nonparametric test to identify if there was a difference in subjective wellbeing scores between travel frequency groups (testing Hypothesis 1).

For subjective wellbeing, we used travel frequency as a nominal variable and analysed whether there were scale score differences between travel frequency groups. The results demonstrated that those who travelled five times or more per year had higher subjective wellbeing scores than those who travelled twice or less per year (Fig. 1). Therefore, hypothesis 1 was supported.

Travel frequency: (1) More than 10 times per year, (2) 5–9 times per year, (3) 3–4 times per year, (4) 1–2 times per year, (5) Once in 2–3 years, (6) Less than once in 2–3 years (Hardly ever); SHS Subjective Happiness Scale. The bar charts show the scale score (mean ± SD). Significant SHS score difference between 1–4/5, 2–4/5, 3–4 (*p < 0.05).

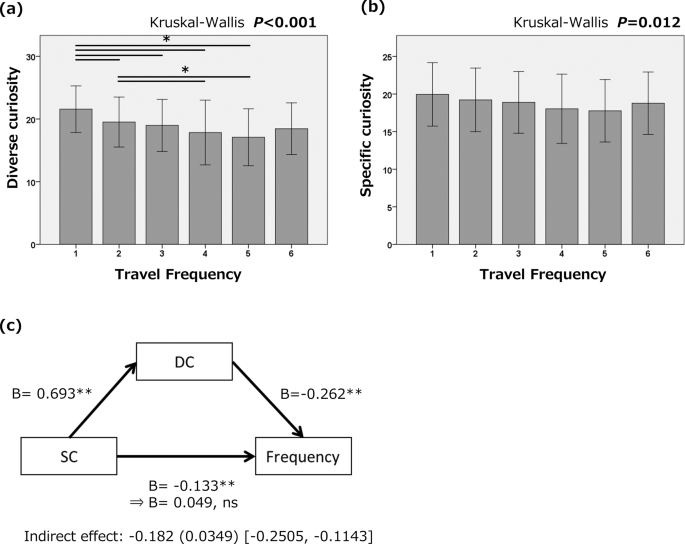

Relationship of epistemic curiosity with travel frequency

Second, to investigate if curiosity motivates tourism, we conducted a nonparametric test to identify whether there was a difference in curiosity scale scores between travel frequency groups (testing Hypothesis 2). The results revealed that those who travel 10 times or more per year have more diverse curiosity than other frequency groups, except for those who do not travel at all (Fig. 2a, Table 3). Furthermore, those who travel five to nine times per year showed more diverse curiosity than those who travel twice or less per year. Curiosity score differences between travel frequency groups were determined by a non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (p = 0.012), although no significant difference was observed with post-hoc pairwise comparison (Fig. 2b, Table 3).

Travel frequency: (1) More than 10 times per year, (2) 5–9 times per year, (3) 3–4 times per year, (4) 1–2 times per year, (5) Once in 2–3 years, (6) Less than once in 2–3 years (Hardly ever), DC diverse curiosity, SC specific curiosity. The bar charts show the test scores (mean ± SD). a Significant DC difference between 1–2/3/4/5, 2–4/5 (*p < 0.05). b Significant SC difference between groups were observed using the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test (p = 0.012), although no significant difference was seen in post-hoc pairwise comparison of Dunn’s test with Bonferroni error correction. c Mediation analysis between DC, SC and travel frequency. The positive effect of SC on travel frequency is completely mediated by DC (**p < 0.01).

Epistemic curiosity consists of diverse curiosity and specific curiosity, which are reported to have a positive correlation (Nishikawa and Amemiya, 2015). To modulate the correlation between the two curiosity components, we conducted a mediation analysis between diverse curiosity, specific curiosity, and travel frequency. After controlling for diverse curiosity, specific curiosity was no longer a predictor for travel frequency (Fig. 2c), and the indirect coefficient was significant (B = −0.182, SE = 0.0349, 95% CI [−0.2505, −0.1143]).

In sum, Hypothesis 2 was supported, but only diverse curiosity among the two components of epistemic curiosity was seen to motivate travel.

Curiosity as a determinant of subjective wellbeing

To investigate the influence of personality on subjective wellbeing, we examined whether trait curiosity correlates with subjective wellbeing (testing of Hypothesis 3). We conducted a correlation analysis between epistemic curiosity and subjective wellbeing scores to investigate whether the personal trait of epistemic curiosity is a determinant of subjective wellbeing.

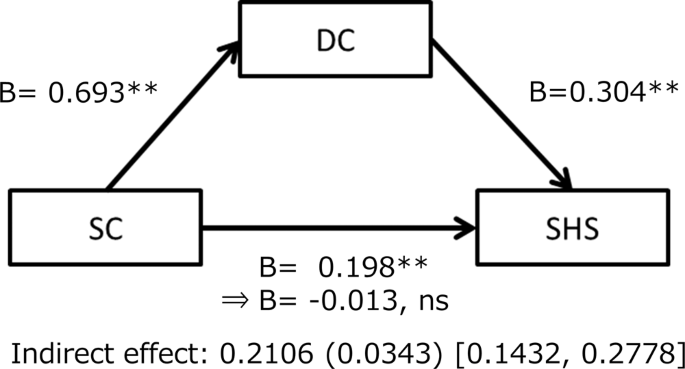

To modulate the correlation between the two curiosity components, we conducted a mediation analysis between diverse curiosity, specific curiosity, and subjective wellbeing scores. After controlling for diverse curiosity, specific curiosity was no longer a predictor of subjective wellbeing (Fig. 3). The indirect coefficient was also significant (B = 0.211, SE = 0.0343, 95% CI [0.1432, 0.2778]). In sum, among the two components of epistemic curiosity, only diverse curiosity acts as a determinant of subjective wellbeing; in other words, the personal trait of diverse curiosity correlates positively with subjective wellbeing, indicating that highly curious people have generally higher subjective wellbeing. Thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Causal model of diverse curiosity, travel frequency, and subjective wellbeing

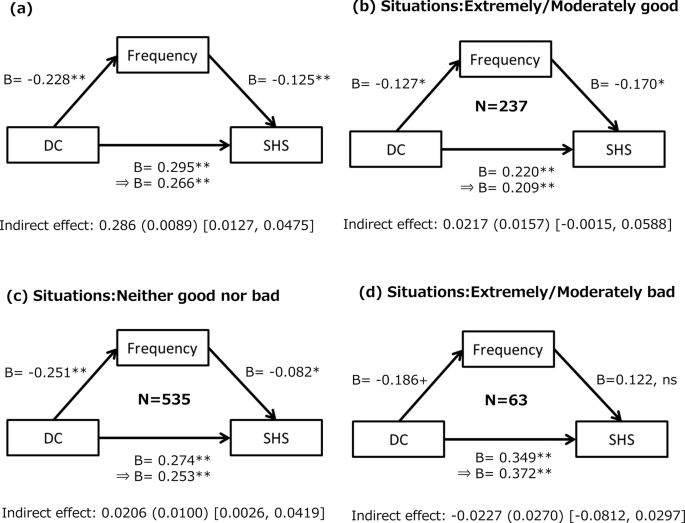

Following the findings that the personal trait of curiosity positively relates to both travel frequency and subjective wellbeing and that travel frequency also positively relates to subjective wellbeing, we conducted a mediation analysis to investigate the causal relationship among the three factors. We proposed that trait curiosity positively affects subjective wellbeing both directly (i.e., curiosity has a top-down influence on subjective wellbeing) and indirectly through travel frequency. We also hypothesized that travel frequency positively correlates with subjective happiness even after it is controlled by trait curiosity (i.e., bottom-up effect of tourism on subjective wellbeing) (hypothesis 4). As the earlier results demonstrated that among the two components of epistemic curiosity, only diverse curiosity motivates travel, we used diverse curiosity but not specific curiosity in the analysis. The results revealed that participants with greater diverse curiosity traits demonstrated greater travel frequency than other participants (B = −0.228, SE = 0.0353, p < 0.001) and that greater travel frequency is related to higher subjective wellbeing (B = −0.125, SE = 0.0322, p < 0.001). Upon testing the significance of the indirect effect using bootstrap estimation with 10,000 resamples, the indirect coefficient was significant (B = 0.286, SE = 0.0089, 95% CI [0.0127, 0.0475]), as was the direct effect of diverse curiosity on subjective wellbeing (B = 0.266, SE = 0.0336, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4a). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 was supported.

Effect of family budget on travel and subjective wellbeing

Since travelling is not an essential activity in daily life, we hypothesized that preference for travel may depend on the family budget situation. Therefore, we also assessed the effect of family budget on the causal model of diverse curiosity, travel frequency, and subjective wellbeing.

Participants were classified into three groups according to whether they considered their family budget situation to be ‘extremely/moderately good’, ‘neither good nor bad’, or ‘moderately/extremely bad’. All three groups demonstrated a significant positive relationship between diverse curiosity and subjective happiness as a total effect (Fig. 4b–d).

The ‘extremely/moderately good’ and ‘neither good nor bad’ groups showed a significant relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing (Fig. 4b, c). This implies that higher travel frequency promotes higher subjective wellbeing. However, the indirect effect of travel frequency on the relationship between diverse curiosity and subjective wellbeing was significant only in the ‘neither good nor bad’ group (B = 0.0206, SE = 0.0100, 95% CI [0.0026, 0.0419]). Even after controlling for travel frequency, diverse curiosity remained a significant predictor of subjective wellbeing. In the ‘extremely/moderately bad’ family budget situation group, higher diverse curiosity was a predictor of higher subjective wellbeing; however, diverse curiosity did not predict travel frequency, which in turn was not related to subjective wellbeing (Fig. 4d). In short, the causal relationship among frequency, subjective wellbeing, and curiosity was modified by the family budget situation. Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Discussion

The primary goal of our study was to investigate whether tourism, in a relationship with curiosity, contributes to the subjective wellbeing of older adults. In addition to establishing the relevant relationships, we also gained a number of interesting findings that contribute to a better understanding of the motivations of tourism and the construct of subjective wellbeing.

Diverse curiosity works as a motivation to travel

As we hypothesized, the personal trait of curiosity showed a positive relationship with travel frequency, indicating that diverse curiosity motivates travel. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing that curiosity drives people to travel and that it relates to subjective wellbeing directly and indirectly through travelling. However, specific curiosity revealed no significant relationship with travel frequency. Nishikawa and Amemiya (2015) conceptualized diverse curiosity as the motivation to widely explore new information, which relates to positive attitudes toward ambiguity and to fun-seeking aspects of the behavioural activation system; these in turn cultivate the attitude required to voluntarily approach novel stimuli. In contrast, specific curiosity refers to the motivation to explore information in order to solve cognitive conflicts, and relates to the preference for order and ambiguity control (Nishikawa and Amemiya, 2015). From the perspective of ambiguity, diverse curiosity then works as a drive to encounter ambiguity, while specific curiosity works as a drive to reduce and exclude it. Based on the results showing that travelling is driven by diverse curiosity, travelling may then be assumed to comprise behaviour directed toward widely seeking novel stimuli, but not seeking specific information. Furthermore, it is intuitively clear that travelling means exploring miscellaneous new information and may increase information ambiguity. From the perspective of specific curiosity, travelling may then not always comfortable, as one may be confronted by uncontrollable ambiguous situations.

Intrapersonal balance of epistemic curiosity may determine ‘appropriate’ travel frequency of individuals

After controlling for diverse curiosity in the mediation analysis to investigate the effect of specific curiosity on travel frequency, the regression coefficient of specific curiosity on travel frequency changed from a plus to a minus sign (Fig. 2c). However, the direct coefficient was not significant (B = 0.049, ns); this may imply that people with high specific curiosity resist travelling, in contrast to those with diverse curiosity. In short, the intrapersonal balance of diverse and specific curiosity may modulate individuals’ interest level and determine their ‘appropriate’ travel frequency, implying that promoting frequent travel may not always result in a positive effect on subjective wellbeing.

The study’s results revealed that curiosity, which is an intrinsic desire for cognitive stimulation, motivates travel. This in turn may support the idea that travelling is a cognitively stimulating activity. Participation in cognitively stimulating activities has been associated with reduced late-life cognitive decline, in the cognitive reserve hypothesis (Wilson et al., 2013; Stern, 2012). Therefore, tourism, which entails cognitively stimulating activity, may contribute to slower late-life cognitive decline. As discussed, however, an individual’s travel frequency may depend on their personal intra-balance of epistemic curiosity. Thus, the question remains as to whether encouraging tourism extrinsically will successfully promote subjective wellbeing. Since there is a possibility that overly frequent travel experiences may induce mental discomfort from the perspective of individual levels of specific curiosity, extrinsically forced tourism experiences may have adverse effects.

Also, as regards the contribution of personal disposition to subjective wellbeing (i.e., the top-down effect of curiosity on subjective wellbeing), diverse curiosity showed a significant positive correlation with subjective wellbeing. This relationship is consistent with reports that greater trait curiosity relates to better subjective wellbeing (Nishikawa et al., 2015; Nishikawa, 2014).

Travel frequency positively affects subjective wellbeing of older adults

Looking into the relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing, we found that participants with higher levels of trait diverse curiosity demonstrated higher scores on subjective wellbeing. Even after controlling for the positive relationships between the personal trait of curiosity and both travel frequency and subjective wellbeing, mediation analysis demonstrated that travel frequency positively correlates with subjective wellbeing; the indirect effect of travel frequency was also significant (Fig. 4a). To our knowledge, this is the first report to show a relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing among older adults. The findings indicate that travel quantity is as important as travel quality.

Family budget situation alters the relationship among travel frequency, subjective wellbeing, and curiosity

The positive relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing was significant only in groups that were not financially constrained (Fig. 4b, c). Also, the relationship between diverse curiosity and travel frequency in individuals with financial restrictions showed less significance than in those with no financial restrictions. In other words, these results suggest that among individuals that have financial restrictions, diverse curiosity does not act as a motivation to travel and travel frequency does not contribute to subjective wellbeing. Thus, taken together, these findings indicate that travel frequency contributes to subjective wellbeing (i.e., there is a bottom-up effect of tourism on subjective wellbeing) but that this effect is limited by family budget.

Having financial difficulties may mean that travelling is unaffordable; even if the family can afford it, it can cause difficulties in terms of making ends meet after travelling. Thus, it makes sense that the contribution of tourism to subjective wellbeing is effective only in those who are well-off and can afford to travel. Additionally, among individuals with financial restrictions, curiosity did not act as a motivation to travel. The information-seeking behaviour involved in diverse curiosity does not have a specific direction with regard to the information or stimuli sought; thus, curiosity may have motivated other information-seeking activities instead of travelling for people with financial restrictions. This relationship also implies that individuals who have financial restrictions experience not merits but demerits to subjective wellbeing, due to not being able to travel.

However, previous studies on low-income families have demonstrated that availability of financial support that allows such families to participate in tourism and holiday breaks increases their quality of life and subjective wellbeing (McCabe and Johnson, 2013; McCabe et al., 2010). Thus, supporting individuals who have the potential to benefit from tourism (i.e. persons with a high diverse curiosity trait) but who cannot afford to travel due to financial difficulties may act as a promising intervention to promote subjective wellbeing among the public. This supports the recognition of the importance of social tourism initiatives to provide opportunities to travel for those that are otherwise unable to participate due to certain disadvantages, including financial difficulties. A relationship between social tourism participation and health self-perception has been also reported, indicating that tourists are more active and healthy than non-tourists (Ferrer et al., 2016).

Besides the fact that travel consumes money, travellers have to deal with complications caused by daily activities (e.g., job, housework, medical care); leisure time, number of family members, and other confounding factors may affect the relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing. Moreover, other factors, such as interpersonal relationships with travel companions, may also influence seniors’ travel behaviour and subjective wellbeing. In the current study, only 22 participants, or 2.6%, answered that they always travel alone. Therefore, the majority of the participants are to some degree concerned with interpersonal relationships with travel companions. Interpersonal relationships may facilitate travel (Huber et al., 2018) and promote subjective wellbeing through travel experiences (Gram et al., 2019); however, this study did not assess what psychological or physiological effects travel companions may modify. Furthermore, the current study was designed to investigate whether travel’s contribution to subjective wellbeing is made in a relationship with trait curiosity, and we focused on the dimension of travel frequency. Therefore, factors such as quality of travel (e.g. travel destination, travel satisfaction, interpersonal relationships) are not taken into account in the analysis. From the current findings, we can only assert that frequent travel positively correlates with subjective wellbeing; however, the effect of travel on subjective wellbeing may also differ among travel destinations, travel companions, travel duration, and other travel quality factors, and therefore further investigation is required to assert a causal relationship between travel frequency and subjective wellbeing.

Furthermore, additional limitations of our study need to be considered. First, the study subjects were recruited from among registered customers of a travel agency. Our study demonstrated that diverse curiosity drives interest in travel and frequent travel, but our study may be limited to those who are already interested in travelling to a certain extent. The information-seeking behaviour of diverse curiosity does not have a specific orientation with regard to the type or location of the information or stimuli sought; there exist multiple potential preferences regarding information sources (e.g., when reading a book, one may prefer reading mysteries, romance novels, non-fiction, or yet another category) (Nishikawa, 2013). Therefore, travel is anticipated to have competition from other information-seeking activities as an object of diverse curiosity. This means that higher levels of diverse curiosity in the general population may not lead directly to higher interest in and frequency of travel. While the findings of the current study indicated that curiosity acts as a motivation to travel among people in their 60s; however, curiosity may motivate other information-seeking activities besides travelling in other age groups. Preference for travelling may also be induced by other cognitive traits, characteristics, age-related life events, or environmental factors, such as satisfaction with former travel experiences; however, this remains unclear from the present study.

We also need to inform the reader that our study was designed to assess the contribution of tourism to subjective wellbeing in the early stage of old age; this is why the subjects’ age range was limited to those in their 60s. This age range was set because of the already active travel status of people in this group, and intervention for subjective wellbeing in this age group is expected to be promising in terms of maintaining cognitive health. However, the relationship of tourism to subjective wellbeing may differ in the later stages of old age, due to socioeconomic status, health problems, or changes in epistemic curiosity level. In trait theory, it is generally assumed that personal traits, including curiosity, are relatively stable over time and consistent over situations. However, it has been suggested by some researchers that personality traits develop and change even through the later stages of life, and that the traits of extraversion and openness steadily decline at the end of life. It has also been reported that poor health results in this personality change (Wagner et al., 2016). Thus, personal psychological and physical states may affect personal traits in the long term, and this effect should be taken into account in future studies.

Another limitation is that the definition of travel/tourism is not specifically discussed in this study. The word ‘travel’ or ‘tourism’ (in Japanese, both words are represented by the term ryokou) was used in the questionnaire, but the definition was dependent on the respondents’ own perspectives. We anticipated that participants would interpret travel using a classical definition, which would be unrelated to the purpose of sharing material through social networking services (SNSs, i.e., Facebook, Instagram, Twitter). Since motives for sharing experiences through SNS may include a desire for self-revelation and recognition, travel may act as one resource for gaining such approval. Therefore, based on such motives, travel may not be the purpose itself, but rather a method. However, in our study, such motives were not seen in the responses to the questionnaire item asking about specific motives for travel. Thus, we expect that the definition of ‘travel’ used in this study did not closely reflect the motive of desire for approval.

Cultural differences may also exist in definitions of travel, and there may be other confounding factors in individual approaches to travel. Therefore, cultural background should be taken into account; further studies should be conducted in this respect.

Finally, we would like to reiterate that the current study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which drastically changed travel behaviour among the world population. The effects of the pandemic on communities, such as travel restrictions, lockdowns, social distancing, restrictions on gatherings, and severe health threat, have already altered the tourism industry and are expected to continue to change travel behaviour post-COVID-19. Thus, changing social conditions need to be considered in future studies.

Conclusion

The present study has demonstrated that diverse curiosity motivates early seniors to travel and that tourism promotes subjective wellbeing in older adults, even though subjective wellbeing is generally affected and predetermined by the personality of curiosity.

We have revealed that people with higher diverse curiosity are more highly motivated to travel and more dedicated to travelling and that their subjective wellbeing is positively affected by travel frequency. Our study thus adds the novel evidence that curiosity acts as a motivation to travel and also that frequency of travel contributes to subjective wellbeing.

Since higher subjective wellbeing plays a protective role toward cognition during aging, our study helps substantiate the potential role of travelling in maintaining public wellbeing. However, high specific curiosity, which may coexist with high diverse curiosity, may not always lead to positive effects of frequent travel. Therefore, unconditional targeted promotion of frequent travel may not be appropriate as an intervention to advance subjective wellbeing among the older adults; instead, promoting travelling for people with suitable personality traits may improve subjective public wellbeing. Additionally, the relationship among travel frequency, curiosity, and subjective wellbeing was modified by financial restrictions, demonstrating that tourism contributing to the subjective wellbeing of only the well-off older adult in general social settings. One way to promote broader subjective wellbeing may be financial assistance for travelling, such as social tourism initiatives to provide opportunities to travel for those otherwise unable to participate due to financial disadvantages.

To sum up the current study contributes to a better understanding of the contribution of tourism to subjective wellbeing among older adults. However, in reality, tourism’s involvement in subjective wellbeing may not be as simply modelled as our study proposes, and may include factors such as interpersonal relationships and dispositions. Therefore, further research is needed to investigate the relevant relationships in terms of other potential confounding factors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available, but can be made available to individuals approved by the ethics committee of Tohoku University.

References

Berlyne DE (1954) A theory of human curiosity. Br J Psychol 45:180–191

Berlyne DE (1966) Curiosity and exploration. Science 153:25–33

Butler J, Ciarrochi J (2007) Psychological acceptance and quality of life in the elderly. Qual Life Res 16:607–615

Chen CC, Yoon S (2018) Tourism as a pathway to the good life: comparing the top-down and bottom-up effects. J Travel Res 58:866–876

Crompton JL (1979) Motivation for pleasure vacation. Ann Tour Res 6:408–424

Diener E (1984) Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 95:542–575

Diener E, Sandvik E, Seidlitz L, Diener M (1993) The relationship between income and subjective well-being: relative or absolute? Soc Indic Res 28:195–223

Diener E, Suh EM, Lucas RE, Smith HL (1999) Subjective well-being: three decades of progress. Psychol Bull 125:276–302

Ferrer JG, Sanz MF, Ferrandis ED, McCabe S, Garcia JS (2016) Social tourism and healthy ageing. Int J Tourism Res 18:297–307

Fritz C, Sonnentag S (2006) Recovery, well-being, and performance-related outcomes: the role of workload and vacation experiences. J Appl Psychol 91:936–945

Fleischer A, Pizam A (2002) Tourism constraints among Israeli seniors. Ann Tour Res 29:106–123

Gilbert D, Abdullah J (2004) Holiday taking and the sense of well-being. Ann Tour Res 13:103–121

Gram M, O’Donohoe S, Schänzel H, Marchant C, Kastarinen A (2019) Fun time, finite time: temporal and emotional dimensions of grandtravel experiences. Ann Tour Res 79:102769

Hatano G, Inagaki K (1971) Hattatu to kyouiku ni okeru naihatuteki doukiduke. Meijitosho Shuppan, Tokyo

Hayes AF (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach, 2nd edn. The Guilford Press, New York

Hirosaki M, Ishimoto Y, Kasahara Y et al. (2013) Positive affect as a predictor of lower risk of functional decline in community-dwelling elderly in Japan. Geriatr Gerontol Int 13:1051–1058

Huber D, Milne S, Hyde KF (2018) Constraints and facilitators for senior tourism. Tour Manag Perspect 27:55–67

Japan tourism agency (2020) Research study on economic impacts of tourism in Japan: Japan national tourism survey 2018. Japan Tourism Agency, Tokyo

Kashidan TB, Steger MF (2007) Curiosity and pathways to well-being and meaning in life: traits, states, and everyday behaviors. Motiv Emot 31:159–173

Kidd C, Hayden BY (2015) The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron 88:449–460

Kim H, Woo E, Uysal M (2015) Tourism experience and quality of life among elderly tourists. Tour Manag 46:465e476

Lee TH, Crompton J (1992) Measuring novelty seeking in tourism. Ann Tour Res 19:732–751

Litman JA, Spielberger CD (2003) Measuring epistemic curiosity and its diversive and specific components. J Pers Assess 80:75–86

Lowenstein G (1994) The psychology of curiosity: a review and reinterpretation. Psychol Bull 116:75–98

Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS (1999) A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res 46:137–155

McCabe S, Johnson S (2013) The happiness factor in tourism: subjective well-being and social tourism. Ann Tour Res 41:42–65

McCabe S, Joldersma J, Li C (2010) Understanding the benefits of social tourism: linking participation to subjective well-being and quality of life. Int J Tour Res 12:761–773

Murata C, Takeda T, Suzuki K, Kondo K (2016) Positive affect and incident dementia among the old. J Epidemiol Res 2:118–124

National institute of Population and Social Security Research (2017) Population Projections for Japan (2017): 2016 to 2065 (Appendix: Auxiliary Projections 2066 to 2115). http://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-zenkoku/e/zenkoku_e2017/pp29_summary.pdf. Accessed 14 Oct 2020

Nishikawa K (2013) A review of experimental studies on the diversive curiosity and specific curiosity. Kandai Psychol Rep 10:71–85

Nishikawa K (2014) The influence of curiosity on health and social relations: applicative study on the individual differences of curiosity. Kandai Psychol Rep 12:33–42

Nishikawa K, Amemiya T (2015) Development of an Epistemic Curiosity Scale: diverse curiosity and specific curiosity. Jpn J Educ Psychol 63:412–425

Nishikawa K, Yoshizu J, Amemiya T, Takayama N (2015) Individual difference in trait curiosities and their relations to mental health and psychological well-being. J Jpn Health Med Assoc 24:40–48

Odaka S, Hibino N, Morichi S (2011) Domestic tourists’ behavior and characteristics based on individual data. J JSCE Ser D3 67:67_I_727-67_I_735

Plog S (1974) Why destination areas rise and fall in popularity. Cornell Hotel Restaur Admin Q 14(4):55–58

Przepiorka AM, Blachnio AP (2017) The relationships between personality traits and leisure time activities: development of the Leisure Time Activity Questionnaire (LTAQ). Neuropsychiatry 7:1035–1046

Shimai S, Otake K, Utsuki N, Ikemi A, Lyubomirsky S (2004) Development of Japanese version of the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), and examination of its validity and reliability. Jpn J Public Health 51:845–853

Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2016) Survey on Time Use and Leisure Activities 2016. https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/shakai/index.html. Accessed 28 Oct 2020

Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (2020) Statistics Topics No. 126. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/topics/topi1261.html. Accessed 28 Oct 2020

Steel P, Schmidt J, Shultz J (2008) Refining the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 134:138–161

Stern Y (2012) Cognitive reserve in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 11:1006–1012

Uysal M, Sirgy MJ, Woo E, Kim H (2016) Quality of life (QOL) and well-being research in tourism. Tour Manag 53:244–261

Wagner J, Ram N, Smith J, Gerstorf D (2016) Personality trait development at the end of life: antecedents and correlates of mean-level trajectories. J Pers Soc Psychol 111:411–429

Wang HY, Karp A, Winbald B, Fratiglioni L (2002) Late-life engagement in social and leisure activities is associated with a decreased risk of dementia: a longitudinal study from the Kungsholmen Project. Am J Epidemiol 155:1081–1087

Wilson RS, Boyle PA, Yu L, Barnes LL, Schneider JA, Bennett DA (2013) Life-span cognitive activity, neuropathologic burden, and cognitive aging. Neurology 81:314–321

Zhang L, Zhang J (2018) Impacts of leisure and tourism on elderly’s quality of life in intimacy: a comparative study in Japan. Sustainability 10(12):4861

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Club Tourism International Inc. We thank the staff from Club Tourism International Inc. who were involved in questionnaire acquisition and all our colleagues at Institute of Development, Aging and Cancer, Tohoku University, for their support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Drafting/revising the manuscript for content: T.T., I.M., and Y.T. Study design and concept: T.T., I.M. and Y.T. Analysis and interpretation of the data: T.T., I.M., and Y.T. Acquisition of the data: I.M. Obtaining funding: Y.T. Correspondence to T.T.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

This work was funded by Club Tourism International Inc.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Totsune, T., Matsudaira, I. & Taki, Y. Curiosity–tourism interaction promotes subjective wellbeing among older adults in Japan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8, 69 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00748-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00748-3