Abstract

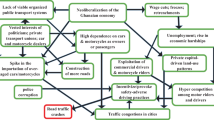

This paper attempts a better explanation for the causes of dangerous driving behaviors among “Tro-Tro”(minibus) drivers in Ghana. The current media, policy, and academic coverage of the problem reveals an immutable discourse that considers the behaviors (such as over speeding) as a function of moral failure, indiscipline, or bad attitudes on the part of the drivers. Often little consideration is given to the context of the behaviors and their influences. This paper provides an alternative explanation that considers the behaviors as predictable actions that are systematically connected to the Tro-Tro industry. Tro-Tro drivers operate within a precarious work climate marked by problems such as low wages; cut-throat competition; high level of job insecurity; imposition of non-negotiable throat-cutting daily fees by car owners and harassments from bribe-demanding corrupt police officers. The exigencies of meeting these numerous financial and other demands of their work, not moral failure, are what fuel dangerous driving behaviors among the drivers. Based on this analysis, the present public policy of using penal populism (i.e., heavy fines and prison sentences) to address road trauma in Ghana is ineffective for inducing safer driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers. Interventions to reduce road transport problems involving such commercial passenger vehicles in Ghana and other developing countries similarly situated must be broad, more-wider reaching and include initiatives that also address the range of political-economic causes, motivations, and constraints that incentivize the drivers to drive dangerously. The paper contributes to the sustainable development goals of ensuring safe and sustainable transport (SDG 11.2), and reducing deaths and injuries from road accidents (SDG 3.6).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2018 Global status report on road safety highlights that the number of annual road traffic deaths has reached 1.35 million. Thus, nearly 3700 people die on the world’s roads every day (WHO, 2018). The burden of this unacceptably high carnage on global roads is disproportionately borne by developing countries. The share of global road deaths in low-income countries (LICs) increased from 12% to 16% during the 2010 to 2013 period, with a road death risk of 24.1 deaths per 100,000 population in 2013 (WHO, 2013). It is estimated that road death risk in Africa—the global capital of road trauma—is at a troubling 26.6 deaths per 100,000 people (WHO, 2018).

The sustainable development goals (SDGs) prioritize transport solutions and investments toward helping countries achieve safer transport systems. Road safety, a key indicator of SDGs 3 and 11, is now a recognized global development priority. To attain the goals of providing safe and sustainable transport (SDG 11.2) and deal with deaths and injuries from road traffic crashes (RTCs) (SDG 3.6) in Africa and other developing countries similarly situated, policymakers will need to be supported with the right knowledge to inform well-targeted interventions. This paper attempts a better explanation for the causes of dangerous driving behaviors among “Tro-Tro” (also called minibus or paratransit) drivers in Ghana.

Ghana has a huge problem with road fatalities, which have increased by 12–15% annually since 2008 (Dotse et al., 2019). In 2001, Ghana was rated as the second highest road traffic accident prone nation among six West African countries, with 73 deaths per 1000 accidents (Haadi, 2014). In 2016, 2084 people were killed through RTCs with additional 10,438 suffering various degrees of injuries (NRSC, 2016). Road trauma is among the top 10 leading causes of death in the country (CDC, 2019). The socio-economic cost of RTCs in Ghana is estimated at 1.6% of the country’s GDP (Haadi, 2014).

The data suggest that a significant number (40%) of road fatalities in Ghana tend to involve commercial passenger vehicles (Dotse et al., 2019) in which “Tro-Tro”—the commonest means of public transport in the country—features strongly. For instance, according to the Motor Transport and Traffic Directorate (MTTD) of the Ghana Police Service, within just the first quarter of 2019, accidents involving Tro-Tro vehicles killed three hundred and injured nearly 2000 people (Rufai, 2019). The number could be much higher given that RTCs are under reported in the country (Salifu and Ackaah, 2012). Okraku (2016) described Tro-Tros as “safety hazards” in Ghana.

Tro-Tro is the most affordable and accessible means of transport in cities in Ghana (Okraku, 2016; Okoye, 2010). With the current service gaps in the public transport system and deep concerns with the climate crisis, ensuring the safety of such highly patronized means of public transport will be critical to maintaining ridership and reducing shifts to personal vehicles. The current media and policy (e.g., Ghana Police Service, 2019; NRSC, 2016), as well as academic (e.g., Amo, 2014; Nyamuame et al., 2015) coverage of Tro-Tro safety problems in Ghana reveals an immutable discourse that considers dangerous driving behaviors (e.g., over speeding and overloading) as a function of moral failure, indiscipline or bad attitudes on the part of the drivers. Often little consideration is given to the context of the behaviors and their influences. This omission is significant for a multiple of reasons.

First, the framing of dangerous driving behaviors as a function of the drivers’ moral failure creates a rather false impression that Tro-Tro drivers in the country are putatively bad people or have inherent preference for over speeding or other adverse driver behaviors. Second, lessons from studies on other commercial passenger transport drivers similarly situated in other African countries (Rizzo, 2011, 2017; Agbiboa, 2016) suggest that such informal public transport drivers operate within a precarious work climate marked by problems such as cut-throat competition; low wages; high level of job insecurity; imposition of non-negotiable throat-cutting daily fees by car owners; harassments from bribe-demanding corrupt police officers. The pressures to meet these numerous financial and other demands of their work, not moral failure, are what incentivize the drivers to undertake the dangerous driving practices that earn them public opprobrium. The organizational principles and structure of Ghana’s Tro-Tro industry are similar to that of other African countries (see Okoye, 2010) which, therefore, suggests that similar factors might be at work in Ghana. Nonetheless, there is little by way of research on how the political economy settlement of Ghana’s Tro-Tro industry contributes to unsafe driving behaviors in the country—the gap in the literature the paper explored. The paper was guided by the following questions:

-

1.

To what extent and in what ways do the political-economic constraints established in the informal public transport literature on other African countries incentivize adverse driver behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana?

-

2.

What lessons could be mined from studying the political economy of Tro-Tro to improve road safety in cities in Ghana?

-

3.

What set of concepts and analytical tools could the study findings contribute to the broader literature on informal public transport in the Global South?

Overall, the paper would argue that, contrary to the received wisdom, dangerous driving behaviors among Ghanaian Tro-Tro drivers are not driven by bad attitudes or moral failure. They are rather predictable actions that are systematically connected to the commercial passenger transport industry in which the drivers operate. The paper, based on this analysis, would argue that the presently embraced public policy of using penal populism (i.e., heavy fines and prison sentences—see Jasmine, 2013; Ghana Police Service, 2019) and even road safety education (GNA, 2018) to address road trauma in Ghana is ineffective for inducing safer driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers. Interventions to reduce road transport problems involving such commercial passenger vehicles in the country and others similarly situated must be broad, more-wider reaching and include initiatives that also address the range of political-economic causes, motivations and constraints that incentivize the drivers to drive dangerously.

The message conveyed in this paper corroborates the growing recognition in the road transport community that accident-inducing errors are usually not the flaws of morally, technically or mentally deficient “bad apples” of road-users but the, often, predictable actions and omissions that are systematically connected to the sociotechnical road transport system in which people traverse (see, for instance, Newnam et al., 2017; Newnam and Goode, 2018; Belzer and Sedo, 2018; Soro et al., 2020; Stevenson et al., 2013; Salmon and Lenné, 2015). The rest of the paper details the message.

Adverse driving behaviors in Ghana: overview of current narratives on causes and a critique

In February 2018, after a series of RTCs in Ghana, the President tasked his Ministers of Interior, Transport, Roads & Highways to investigate and come up with a working solution to address the menace. “Indiscipline”, the Committee reported, is “the main contributory factor to the increasing incidents of road traffic crashes” in Ghana (Ghanaweb, 2019). The conclusion of the President’s Committee is consistent with the popular view in Ghana that road accidents in the country are caused by bad attitudes of individual road-users—particularly drivers. Parliamentarians (Ghanaweb, 2018); Former Presidents (PeacefmOnline, 2019); ministers of state (Gobah, 2019); the National Roads Safety Commission (Ghanaweb, 2019); the police and the media (Ghana Police Service, 2019) often blame drivers for the carnage on Ghana’s roads.

Similar claims are made within the realm of academia and research. For instance, Nyamuame et al. (2015) argue that over speeding; overloading and disregard for road signs/regulations, the three main causes of road fatalities in Ghana, are closely related to drivers’ behavior such as negligence and indiscipline. Amo (2014) contends that bad driver attitude, rather than vehicles, must be blamed for road fatalities in Ghana. Amedorme and Nsoh (2014) too argue that driver related factors such as careless driving, drunk driving and use of phones while driving are major causes of road deaths in Ghana. One study claims that in 77% of cases where human error was at the crux of road accidents in Ghana, drivers were at fault in 56.2% of them (see Singh et al., 2016). Haadi (2014), Siaw et al. (2013), and Coleman (2014) too project a driver-blaming approach to RTCs in Ghana—and, thus, attribute road fatalities in the country to bad attitudes on the part of drivers.

As noted earlier, Tro-Tro is the commonest means of public transport in Ghana (Asiedu-Larbi, 2017; Okraku, 2016; Rufai, 2019), therefore, the drivers tend to feature strongly in road transport problems in the country. The framing of dangerous driving behaviors in the Ghanaian policy, media and academic circles as a function of moral failure or bad attitudes on the part of individual drivers is largely problematic. Not only does the discourse create a rather false impression that Tro-Tro drivers are putatively bad people or have inherent preference for speeding and other adverse driver behaviors, it also sits in tension with the long established sociological thought (see The Sociological Imagination, 1959 of C Wright Mills, for instance) that the true causes of social problems are usually not to be found within the personal situations or characteristics of the implicated individuals—they tend to lie with the larger social contextual forces that act on them. This, therefore, calls for alternative explanations for dangerous driving that consider factors beyond the personal attitudes of Tro-Tro drivers.

Encouragingly, there is a groundswell of research (Rizzo, 2011, 2017; Agbiboa, 2016; Klopp and Mitullah, 2016; Klopp et al., 2019; Behrens et al., 2016; McCormick et al., 2016, 2016b) in other parts of Africa that explores the behavior of commercial passenger transport drivers against the backdrop of the political economy settlement of the informal public transport industry in which they operate. The next section distills some of the lessons and ideas accrued in the literature to provide a better explanation for dangerous driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana.

Adverse driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers: a function of political economy not moral failure

Publicly run and undersupplied since colonial times, Ghana’s road transport sector has progressively evolved into a privately run, deregulated industry (for a review of the evolution of Ghana’s road transport sector, see Okraku, 2016; Clayborne, 2012; Hart, 2016). There are other means of public transport such as coaches and taxis in Ghana, however, Tro-Tro is the most popular means of public transport in the country—particularly in the cities. The term “Tro-Tro” originated from the initial fares charged by the buses (one “tro” or pence per trip). The phrase is also associated with this form of transport as an affordable means of travel for people of all economic means (Okoye, 2010). Although the name of the minibus is a local one, similar minibuses are a major form of transport in other African cities (with their own local names, such as danfos in Nigeria, daladalas in Tanzania and matatus in Kenya).

As with the informal commercial transport sectors of other African countries (McCormick et al., 2016; Rizzo, 2011, 2017; Agbiboa, 2016), Ghana’s Tro-Tro industry is organized around a target system—where the driver (usually a male) and his “mate” or assistant operate the bus as a sort of daily franchise, for which the owner demands a daily fee (commonly called “sales”). The daily return for the crew (the driver and the mate) will consist of what remains once the “sales” has been made and the cost of fuel—towards which car owners do not contribute—has been deducted. Currently, there is little by way of research on how this target system influence Tro-Tro drivers’ behavior in the country. However, lessons from studies on other informal commercial transport workers in other parts of Africa (e.g., Rizzo, 2011; Agbiboa, 2016), as well as the accounts of some Tro-Tro drivers captured in both Dotse et al. (2019) and a recent documentary by Citi 97.3 FM suggest that the power relations inherent in the target system could be key to making sense of Tro-Tro drivers’ behaviors in the country.

The relationship between car owners and the drivers, often unmediated by the state, takes place on an atomized basis, whereby car owners (unilaterally) “agree” to the terms and conditions of work with drivers on a one to one basis. As Rizzo puts it, “no ‘struggle between classes’ is observable in the passenger transport system” (Rizzo, 2011; p. 1186). The salient point here is that many African cities are plagued by high levels of unemployment, the passenger transport sector, therefore, attracts plenty of labor with many reserved armies of drivers ever-hungry for opportunities (Agbiboa, 2016). This tilts the balance of power between drivers and owners in favor of the latter as the two parties “negotiate” the daily fee. As one driver bemoaned in a study on the situation in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: “they [bus owners] can ask you whatever [daily sales or fees] they want and you have to accept it” (Rizzo, 2011; 1186). Agbiboa (2016) and McCormick et al. (2016a, 2016b) made similar findings in Lagos, Nigeria and Nairobi, Kenya; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania and Cape Town, South Africa.

The power asymmetry, thus, condemns the drivers, who usually have dependants, to great occupational uncertainty, extremely harsh working conditions and meager returns. Their situation is further worsened by the ever-present bribe-demanding corrupt police and “hard-core” dues collecting union officers who have created predatory economies across passenger transport sectors in Africa by extorting monies from drivers (see Agbiboa, 2015, 2016, for instance). The drivers could only make enough revenue to cover operational costs and the police bribes, pay their owners, themselves, and their mates (assistants) only by increasing the number of trips or passengers per trip. They, invariably, therefore, are forced or incentivized to drive for long hours, resort to dangerous overtaking, overload their cars and drive at dangerously high speeds. Thus, the drivers’ unsafe driving behaviors are intimately connected to the precarious conditions associated with the commercial passenger transport industry in which they operate.

The above analysis finds empirical corroboration in many of the studies conducted on commercial passenger transport across the African continent. For instance, in Life is War: Informal Transport Workers and Neoliberalism in Tanzania and No condition is permanent, Matteo Rizzo (2011) and Daniel Agbiboa (2016) show how the pressures of hyper-competition; low wages; high level of job insecurity; imposition of non-negotiable throat-cutting daily fees by car owners and the activities of corrupt police officers fuel dangerous driving practices such as over speeding and overloading, dangerous overtaking and other aggressive driving behaviors among daladala and danfo drivers in Tanzania and Nigeria. Klopp and Mitullah (2016), Klopp et al. (2019), Rizzo (2011, 2017), Behrens et al. (2016), and McCormick et al. (2016, 2016b) made similar findings in other African countries, including Kenya, Tanzania, and South Africa.

As noted earlier, the organizational principles and structure of Ghana’s Tro-Tro industry are similar to that of other African countries, which, thus, suggests that similar factors might be at work in Ghana. In fact, the accounts of some Tro-Tro drivers captured in Dotse et al. (2019) and in a recent documentary about the conditions of their work (see Citi 97.3 FM, 2019) highlight many of the political-economic constraints that are influencing dangerous driving behaviors among drivers in other African countries. This suggests that the issue of dangerous driving among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana must be understood against the backdrop of the precarious commercial passenger transport industry or environment in which they operate. This, however, is not how the Ghanaian public, media, the police, road safety institutions, practitioners and researchers frame and explain the problem. As shown earlier, the current media and policy (e.g., Ghana Police Service, 2019; NRSC, 2016), as well as academic (e.g., Amo, 2014; Nyamuame et al., 2015) coverage of road transport problems in Ghana reveals an immutable discourse that considers dangerous driving behaviors as a function of drivers’ moral failure, indiscipline or bad attitudes.

However, the Ghanaian situation is not exceptional in what seems to be transpiring as a broader phenomenon in many a developing country where dangerous driving tends to be blamed on the unruliness and bad attitudes of drivers. See Udodiong (2016) for some accusations by the Federal Road Safety Commission of Nigeria; Harare 24 News (2016) and Musinga (2016) for something similar from the Traffic Safety Council of Zimbabwe and the Uganda’s National Road Authority, respectively. Kinyanjui (2019) and Taarifa (2017) too capture similar blames put forward by Kenya’s National Highway Authority and the Rwanda National Police. Not just Africa, in Asia—another hotbed for road fatalities (Dandona et al., 2006; Wismans et al., 2016)—such driver-blaming discourse is ubiquitous (see Xinhua, 2019; Farhin, 2018; Ramaswamy, 2014, for instance).

Conclusion

The correspondence reviewed the attribution of road transport problems involving Tro-Tros in Ghana to the (bad) attitudes of the implicated drivers. It has been shown that, similar to minibus drivers in sister-African countries, Ghanaian Tro-Tro drivers operate within a precarious work climate marked by cut-throat competition; low wages; high level of job insecurity; imposition of non-negotiable throat-cutting daily fees by car owners and harassments from bribe-demanding corrupt police officers. The exigencies of meeting these numerous financial and other demands seem to be what incentivize the drivers to undertake dangerous driving behaviors that earn them public opprobrium. Thus, contrary to popular opinion, the accident-inducing errors are not the flaws of morally deficient “bad apples” of Tro-Tro drivers but the, often, predictable actions that are systematically connected to their work.

In short, the correspondence argues that the extant discourse in Ghana that vilifies Tro-Tro drivers and attributes dangerous driving practices such as over speeding to their personal attitudes hides more than it reveals. It is more insightful to consider the behaviors as structurally interwoven into the political economy settlement of the Tro-Tro industry in which the drivers operate. Based on this analysis, the widely embraced penal populism of using prison sentences (Jasmine, 2013) and imposition of heavy fines (Ghana Police Service, 2019) on drivers to address road transport problems is not effective for inducing safer driving among Tro-Tro drivers. As the analysis shows, the unsafe driving behaviors are not attitudinally-grounded to be simply addressed through sanctions or even education. They are rather embedded or systematically connected to the drivers’ work processes and working conditions, as well as the broader road transport sector/environment in which they operate.

Measures to reduce the behaviors must, therefore, be broad, more-wider reaching and include initiatives that address the range of political-economic causes, motivations and constraints that incentivize them to drive dangerously. For instance, making or enforcing policies that enhance Tro-Tro drivers’ working conditions or job security may bring better road safety outcomes than declaring “wars” on them—the kind of interventions being pursued vigorously in Ghana today (Ghana Police Service, 2019). Road safety matters and the status quo of blaming dangerous driving behaviors on drivers’ moral failure without any systematic engagement with the range of agencies, causes, motivations or constraints that provoke the behaviors is a hindrance to achieving safer roads in Ghana and other developing countries similarly situated.

In terms of literature contributions, the paper brings a political-economic perspective to the current attitude-centered literature on driving behavior in Ghana and other parts of the developing world and, therefore, gives impetus to the growing call in the road transport community (see for instance, Newnam et al., 2017; Newnam and Goode, 2018; Belzer and Sedo, 2018; Soro et al., 2020; Stevenson et al., 2013; Salmon and Lenné, 2015) for a deeper focus on the range of agencies, causes, motivations or constraints that provoke adverse road-user behaviors or fail to prevent them from resulting into accidents, as opposed to road-users’ personal attitudes and characteristics. The essay hopes to stimulate further conversation among road safety practitioners and researchers in Ghana and other similarly situated developing countries toward designing analytical frameworks and tools for collecting the right information on the causes of accidents so that prevention efforts could target the right elements in the transportation system. Not just drivers and for that matter any other road-users.

References

Agbiboa DE (2015) Policing is not work: it is stealing by force: corrupt policing and related abuses in everyday Nigeria. Afr Today 62(2):95–126

Agbiboa DE (2016) ‘No condition is permanent’: informal transport workers and labour precarity in Africa’s largest city. Int J Urban Regional Res 40(5):936–957

Amedorme SN, Nsoh SN (2014) Analyzing the causes of road traffic accidents in Kumasi metropolis. Int J Eng Innov Res 3:895–899

Amo T (2014) The influences of drivers/riders in road traffic crashes in Ghana between 2001 and 2011. Glob J health Sci 6(4):49

Asiedu-Larbi R (2017) Comparative study of safety of taxi and trotro in the Kumasi Metropolitan Area (Master dissertation, Department of Civil Engineering, KNUST -Ghana)

Behrens R, McCormick D, Mfinanga D (2016) Paratransit in African cities: operations, regulations and reform. Routledge, New York, NY

Belzer MH, Sedo SA (2018) Why do long distance truck drivers work extremely long hours? Economic Labour Relat Rev 29(1):59–79

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2019) CDC in Ghana. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/countries/ghana/pdf/Ghana_Factsheet.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020

Citi 97.3 FM (2019) Commercial drivers struggle to live on 300 cedis monthly earnings-Business Dashboard. Retrieved: https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=2711089005784706

Clayborne DD (2012) Owner-drivers in the tro-tro industry: a look at jitney service provision in Accra, Ghana (Doctoral dissertation, UCLA)

Coleman A (2014) Road traffic accidents in Ghana: a public health concern, and a call for action in Ghana, (and the Sub-Region). Open J Preventive Med 4:822–828

Dandona R, Kumar GA, Dandona L (2006) Risky behavior of drivers of motorized two wheeled vehicles in India. J Saf Res 37(2):149–158

Dotse J, Nicolson R, Rowe R (2019) Behavioral influences on driver crash risks in Ghana: a qualitative study of commercial passenger drivers. Traffic Inj Prev 20(2):134–139

Farhin N (2018) Are drivers alone responsible for road accidents in Bangladesh? Available: https://www.dhakatribune.com/bangladesh/2018/04/24/drivers-alone-responsible-road-accidents-bangladesh. Accessed 19 May 2020

Ghana News Agency (GNA) (2018) NRSC launches 2018 Easter Road Safety Campaign: https://www.ghananewsagency.org/social/nrsc-launches-2018-easter-road-safety-campaign-130351. Accessed 19 May 2020

Ghana Police Service (2019) News release: police administration collaborates with CITI TV to check indiscipline on the roads. https://police.gov.gh/en/index.php/news-release-police-administration-collaborates-with-citi-news-to-check-indiscipline-on-the-roads/. Accessed 19 May 2020

Ghanaweb (2018) Parliament summons transport minister over rising road accidents. Available: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Parliament-summons-transport-minister-over-rising-road-accidents-698412. Accessed 19 May 2020

Ghanaweb (2019) Indiscipline leading cause of road accidents-Road Safety Commission reveals. Available: https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Indiscipline-leading-cause-of-road-accidents-Road-Safety-Commission-reveals-732820. Accessed 19 May 2020

Gobah T (2019) Indiscipline on our roads killing us-Transport Minister cries out. Available: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/ghana-news-indiscipline-on-our-roads-killing-us-transport-minister-cries-out.html. Accessed 19 May 2020

Haadi AR (2014) Identification of factors that cause severity of road accidents in Ghana: a case study of the northern region. Int J Appl Sci Technol 4(3):242–249

Harare 24 News (2016) Traffic safety council of Zimbabwe blames motorists. Retrieved from: Available: http://www.harare24.com/index-id-News-zk-50994.html. Accessed 19 May 2020

Hart J (2016) Ghana on the go: African mobility in the age of motor transportation. Indiana University Press, Bloomington

Jasmine A (2013) 14 Drivers arrested for unruly behaviour: Available: https://www.graphic.com.gh/news/general-news/14-drivers-arrested-for-unruly-behaviour.html. Accessed 19 May 2020

Kinyanjui, M (2019) Indiscipline makes Mombasa Road Nairobi’s deadliest—Kenha. Available: https://www.the-star.co.ke/counties/nairobi/2019-03-20-indiscipline-makes-mombasa-road-nairobis-deadliest--kenha/. Accessed 19 May 2020

Klopp JM, Mitullah W (2016) ‘Politics, policy and paratransit: a view from Nairobi’. In: Behrens R, McCormick D, Mfinanga D (eds) Paratransit in African cities: operations, regulations and reform. Routledge, New York, NY

Klopp, JM, Harber J, Quarshie M (2019) A review of BRT as public transport reform in African cities. VREF Research Synthesis Project Governance of Metropolitan Transport

McCormick D, Herrie S, Mfinanga D (2016) ‘The nature of paratransit operations’. In: Behrens R, McCormick D, Mfinanga D (eds) (2016) Paratransit in African cities: operations, regulations and reform. Routledge, New York

McCormick D, Mitullah W, Chitere P, Orero R, Ommeh M (2016b) Matatu business strategies in Nairobi. Paratransit in African cities: operations, regulations and reform. Routledge, New York, NY

Mills CW (1959) The sociological imagination. Oxford UP, New York, NY

Musinga N (2016) Indiscipline is the main reason why there’s road carnage on roads especially Masaka road, Musinga notes. Available https://twitter.com/ntvuganda/status/758167007988740096. Accessed 19 May 2020

Newnam S, Goode N (2018) Don’t just blame the driver–there’s more than one cause of fatal truck crashes. In: Conversation, vol. 24. Conversation Media Group.

Newnam S, Goode N, Salmon P, Stevenson M (2017) Reforming the road freight transportation system using systems thinking: an investigation of Coronial inquests in Australia. Accid Anal Prev 101:28–36

NRSC (2016) Road traffic crash statistics–2016: general overview of the road safety situation: http://www.nrsc.gov.gh/images/statistics/ROAD-TRAFFIC-CRASH-STATISTICS-2016.pdf. Accessed 19 May 2020

Nyamuame GY, Aglina MK, Akple MS, Philip A, Klomegah W (2015) Analysis of road traffic accidents trend in Ghana: causing factors and preventive measures. Int J Eng Sci Manag Res 2(9):127–132

Okoye V (2010) Report from the field: the Tro-Tro-an essential mode of transport in Accra, Ghana: https://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2010/09/29/report-from-the-field-the-tro-tro-an-essential-mode-of-transport-in-accra-ghana/. Accessed 19 May 2020

Okraku TK (2016) “Biribiara Wo Ne Mmerε”(everything has its time): exploring changing perceptions of transportation on film from the colonial gold coast to contemporary Ghana. Afr Today 62(4):45–64

PeacefmOnline (2019) Indiscipline & sheer recklessness cause of road deaths–rawlings. http://www.peacefmonline.com/pages/local/news/201903/378485.php. Accessed 19 May 2020

Ramaswamy R (2014) Indiscipline, the main villain on roads. Retrieved: https://www.dnaindia.com/mumbai/report-indiscipline-the-main-villain-on-roads-1993311. Accessed 19 May 2020

Rizzo M (2011) ‘Life is war’: informal transport workers and neoliberalism in Tanzania 1998–2009. Dev Change 42(5):1179–1206

Rizzo M (2017) Taken for a ride: grounding neoliberalism, precarious labour, and public transport in an African Metropolis. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Rufai NA (2019) Ghana commercial transport system-trotro. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4eS-rzJKkbY&fbclid=IwAR3weDsnfgMHk6v2vtnthH9DTB2fNaN0OTeuHR2BYCs_9xxgdFXtNG0Bolo. Accessed 19 May 2020

Salifu M, Ackaah W (2012) Under-reporting of road traffic crash data in Ghana. Int J Inj control Saf promotion 19(4):331–339

Salmon PM, Lenné MG (2015) Miles away or just around the corner? Systems thinking in road safety research and practice. Accid; Anal Prev 74:243

Siaw NA, Duodu E, Sarkodie KS (2013) Trends in road traffic accidents in Ghana; implications for improving road user safety. Int J Humanities Soc Sci Invent 2(11):31–35

Singh H, Kushwaha V, Agarwal AD, Sandhu SS (2016) Fatal road traffic accidents: causes and factors responsible. J Indian Acad Forensic Med 38(1):52–54

Soro WL, Haworth N, Edwards J, Debnath AK, Wishart D, Stevenson M (2020) Associations of heavy vehicle driver employment type and payment methods with crash involvement in Australia. Saf Sci 127:104718

Stevenson MR, Elkington J, Sharwood L, Meuleners L, Ivers R, Boufous S, Norton R (2013) The role of sleepiness, sleep disorders, and the work environment on heavy-vehicle crashes in 2 Australian states. Am J Epidemiol 179(5):594–601

Taarifa (2017) Rwanda Police reveals who is causing more accidents on highways. Retrieved from: https://taarifa.rw/2017/05/22/here-is-what-experts-are-discussing-about-poor-african-traders/. Accessed 19 May 2020

Udodiong I (2016) ‘Indiscipline is responsible for accidents along Lagos-Ibadan Expressway’–FRSC. Retrieved from: https://www.pulse.ng/news/road-traffic-crashes-indiscipline-is-responsible-for-accidents-along-lagos-ibadan/zmznt68. Accessed 19 May 2020

Wismans J, Skogsmo I, Nilsson-Ehle A, Lie A, Thynell M, Lindberg G (2016) Commentary: status of road safety in Asia. Traffic Inj Prev 17(3):217–225

World Health Organization (WHO) (2013) Global status report on road safety 2018. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (WHO) (2018) Global status report on road safety 2018. World Health Organization, Geneva

Xinhua (2019) Feature: Nepal introduces “Tea with driver” program to reduce highway traffic accidents. Retrieved: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-08/22/c_138329661.htm. Accessed 19 May 2020

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the following people for providing helpful comments on an earlier draft of the paper: my wife, Mrs Magdalene Nkrumah-Boateng of Agricultural Development Bank, Makola-Accra; Dr Jackie Klopp of the Earth Institute of Columbia University, New York and Martin Acheampong of the School of Social Sciences, University of Bamberg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Boateng, F.G. “Indiscipline” in context: a political-economic grounding for dangerous driving behaviors among Tro-Tro drivers in Ghana. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0502-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0502-8