Abstract

The art and craft of science advice is not innately known by those scientists who choose to step out of the lab or the university to engage with the world of policy. Despite a wealth of literature on the ‘science of science advice’, in nearly every situation there is no ‘teacher’ of science advice; it is a typical case of learning on the job. Within that context, the learning of scholars engaging in expert advice is always situated and can sometimes be transformative. To date, however, there has been no systematic, in-depth research into expert advisers’ learning—instead focusing mostly on policymakers’ and publics’ learning about science. In this article, I suggest that such a research programme is timely and potentially a very fruitful line of inquiry for two mains reasons. First, in the case of environmental and climate issues—the focus of the paper—it has become ubiquitous to talk about the need for transformative change(s) towards sustainable futures. If scholars are going to advocate for and inform transformations beyond academia, then in doing so they ought to also take a harder look at how they themselves are transforming within. Specifically, the article illustrates how qualitative research on advisers’ learning can contribute to our understanding of how experts are adapting to changing circumstances in science–policy interactions. Second, it is argued that research on advisers’ learning can directly contribute to: (i) guidance for present and future advisers (especially early-career researchers wishing to engage with policy) and organisational learning in science–policy organisations; and (ii) improving policy-relevance of research and the design of impact evaluations for research funding (e.g. Research Excellence Framework). With the hope of stimulating (rather than closing off) innovative ideas, the article offers some ways of thinking through and carrying out such a research programme. As the nature of both science and policymaking continues to change, the learning experiences of expert advisers is a bountiful resource that has yet to be tapped into.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In relation to environmental and climate issues, it has become ubiquitous for researchers to talk about the transformative changes needed to achieve sustainable futures (see Moser, 2016; Scoones et al., 2020). For example, at its latest Plenary session, the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)—often called the ‘IPCC for biodiversity’—agreed to initiate the scoping of an assessment on the determinants of transformative change for achieving the 2050 Vision for Biodiversity (IPBES-7/1/)Footnote 1. Meanwhile, ‘sustainability researchers and educators have viewed learning as an active and social process of transformation’ (Budwig, 2015, p. 99). They have increasingly referred to the need for adaptive learning (e.g. Armitage et al., 2008), social learning (e.g. Wals, 2009), organisational learning (e.g. Pallett and Chilvers, 2015), and transformative learning (e.g. König, 2015). Since it was first put forward by Jack Mezirow (1978), the concept of transformative learning has had its own share of transformations (cf. Mezirow and Associates, 2000; Kitchenham, 2008). The idea of transformative learning has become particularly appealing to sustainability researchers because it has come to signify paradigm shifts not only at the individual level, but also at the collective levelFootnote 2. Whether in IPBES assessment reports or in peer-reviewed journals, the implicit and often unacknowledged plea is that hoped-for societal transformations—and associated learning—can and should be informed by scienceFootnote 3. I suggest however, that in times of change, uncertainty, and the apparent fragility of academia’s place in western societies, researchers ought to turn the gaze inwards and ask themselves: how are we transforming within science to better inform and support transformations in society beyond? Here, I offer one currently unused lens through which to address this question: science advisers’ learning.

Expert adviceFootnote 4 for policymaking can come from various sectors of society: from within government and policy organisations, from industry or civil society, and—albeit less often—from lay experts. Here, I focus specifically on academics (generally working in a university) who take on temporary positions in advisory bodies or advisory functions for the government or policymakers. By ‘policymakers’ I broadly mean (influential) actors within government departments, the legislative branch (e.g. Parliament), and/or organisations with statutory powers (e.g. non-departmental public bodies), who are chiefly concerned with policy formulation and evaluation as opposed to enforcement. I focus on academics for a number of interrelated reasons: (i) the processes of policymaking are often poorly understood amongst academics (Andrews, 2017); (ii) in relation to climate change, for example, most of the literature has focused on how to make science advice more effective rather than investigating the experiences of science advisers themselves (Selin et al., 2017); and (iii) I build on a particular lineage of scholarship that has taken scientific advisory bodies to be central sites of the interactions between science, policy, and society (see Jasanoff, 1994; Bijker et al., 2009; Owens, 2015). Moreover, the sporadic nature of academics’ appointments as advisers (generally short-term or part-time) suggests the learning experiences of academics are more likely to be associated with discrete events or anecdotes; hence potentially more conducive to being studied.

In stepping out of the lab or the university, and through their engagements with the policy world, these academics learn how to become ‘more effective within an existing policy paradigm’ (Owens, 2015, p. 10). They become more ‘policy literate’—that is knowledgeable of the intricacies of the policy clockwork and the inner workings of government (Selin et al., 2017). Their perceptions of their role as advisers is influenced both by their personal experiences and by the cultures of the institutions within which they work (Spruijt et al., 2014; Porter and Dessai, 2017). Evidently, they are holders of valuable knowledge and experience across science and politics, and yet their personal journeys have seldom been the object of academic study. Many of their experiences have thus far gone unrecorded and their know-how largely untapped. Instead, studies have tended to focus on policymakers’ learning (e.g. Dunlop, 2009) and too little attention has been paid to academics’ learning in acting as expert advisers. I offer some suggestions for how such research could be a fruitful exercise.

My proposition is that researchers in the social sciences and humanities need to take a much harder look at how experts are learning to advise and influence policymakers. How and what are they learning? Are some of these lessons transferable to less experienced, early-career researchers? Which initial assumptions turned out to be wrong? Are some of these assumptions commonly held in academia? In their experience, what (advisory) settings have been most effective, and why? Have circumstances and expectations noticeably changed in recent decades, and in what ways? By asking some of these questions we can begin to formulate an idea of how expert advice works in particular organisations or geographies, the steepness of experts’ learning curve when advising policymakers, and the extent to which lessons learnt can benefit current and future generations of researchers. This sort of research can also contribute to the question of whether (if at all) the relationship between science and policy has markedly changed in recent years.

First, I outline some possible ways of conceptualising advisers’ learning—arguing that while it can sometimes be transformative, it is always necessarily situated. Following Gluckman and Wilsdon (2016), I then recast science advice as an evolving (eco)system that expert advisers must become part of and to which they must continuously adapt. For those reasons, I contend that qualitative research on advisers’ learning is one possible empirical entry point for understanding the extent to which, and in what ways, experts are adapting to new circumstances in science-policy. Drawing mostly from a reading of the UK context, I offer some additional reasons why turning to expert advisers’ (untapped) knowledge can inform both ‘science for policy’ and ‘policy for science’Footnote 5. Specifically, I suggest three benefits of the pragmatic findings such a research programme could yield: (i) they could complement and evaluate existing guidelines for scientific advisers (especially for early-career researchers); (ii) they could assist organisational learning in science-policy institutions; and (iii) they could improve the design of impact evaluation frameworks that guide research funding decisions. In the concluding section, I offer some preliminary thoughts on how such a research programme could be carried out and highlight some of the difficulties in doing so.

The ‘learning’ as opposed to the ‘learned’ adviser

Political expectations of science are not static; rather they are constantly being renegotiated and reconstituted by changing values and perceptions of the role of science in society. Furthermore, this role of science can never be defined and delimited in a clear-cut fashion. Scientists are left to rely on their own sense of the ‘demand for science’ and, in turn, how they perceive the demand drives the ‘characteristics of supply’: the knowledge and advice they choose to highlight at the expense of alternatives (Sarewitz and Pielke, 2007; Stirling, 2010; Wilsdon, 2014). Expert advisers choose to consolidate or revisit their perceptions and strategies based on their encountersFootnote 6 with policy. These encounters are not necessarily face to face. In fact, most advisory bodies operate within their own space, at the boundary between scientific institutions and the institutions of governmentFootnote 7. Through these encounters, expert advisers learn how to navigate the various networks of science advice, and how to become constituent parts of them. They learn how to navigate the tension between demand-driven science advice and the constraints of apparent objectivity and impartiality (Cooper, 2016). They learn how to strategically deploy and cross the boundary between science and policy, between scientific and non-scientific knowledgeFootnote 8 (Turnpenny et al., 2013; Owens, 2015; Boswell, 2018; Palmer et al., 2018). They learn how to become knowledge brokers (Pielke, 2007; Turnpenny et al., 2013; Turnhout et al., 2013). Overall, they learn what constitutes credible, salient, and legitimate advice in the eyes of their advisees (Cash et al., 2003).

Such learning is often incremental, but in some cases may be transformative. Despite its positive connotations transformative learning need not always be a positive experience, nor does it necessarily lead to deep transformations. On the one hand, some academics engaging in the business of advice-giving may be disheartened by the difficulty of getting scientific evidence to bear on policymaking. In some cases, their political engagement may compromise their academic careers. They may also witness instances of what they would consider ‘policy-based evidence-making’ as opposed to evidence-based policymaking. On the other hand, Mezirow (1995) accounted for two types of transformation, namely ‘straightforward transformation’ and ‘profound transformation’ (Kitchenham, 2008). While straightforward transformation can be arrived at through either ‘content reflection’ or ‘process reflection’, profound transformation can only occur through ‘premise reflection’ (i.e. a more global and mindful interrogation of one’s own assumptions and value system) (Kitchenham, 2008). There will be instances where advisers learn to adjust their existing worldviews to fit within particular policy paradigms, and other instances where (sometimes the same) advisers have to reconsider enduring assumptions and expectations about what it means to advise, in the first place.

Moreover, there are a multitude of ways in which science advice is produced and circulated. In the UK for instance, these settings are sometimes formal and commissioned—such as the Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution which was abolished in 2011—or informal and ad hoc (within government departments or an organisation like the Centre for Science and Policy, in Cambridge). Approaches to studying expert advisers’ learning should therefore begin with the acknowledgement that learning is both internal to the individual and situated within particular environments or organisations. Like any form of ‘adult learning’ (i.e. in the workplace as opposed to the classroom), advisers’ learning is largely contingent on pre-existing ‘mental maps’, values, knowledge, and perceptions of their institutional environments (Dunlop, 2009). Indeed, advisers’ learning is strongly shaped by the social and material circumstances within which the adviser operates (Pallett and Chilvers, 2015; König, 2015). It follows that any appreciation of advisers’ learning must combine both an appraisal of individual experience and of the environments within which that experience occurs. On that account, one possible way of studying advisers’ learning is through the lens of ‘situated learning’ in ‘communities of practice’, an idea originally put forward by Lave and Wenger (1991).

For Lave and Wenger (1991), learning is inextricably situated within social communities. Learning happens within and in relation to specific communities of practices, which Wenger later described as ‘groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly’ (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015, p. 1). The conditions of the various social practices—embedded in these communities—define and determine the possibilities for learning. As newcomers engage in these social practices, they learn new knowledge and skills, but also how to become a member of said communities (Lave and Wenger, 1991). This process of socialisation into and learning within communities of practice is what Lave and Wenger (1991) call ‘legitimate peripheral participation’Footnote 9. The participation of an individual is conceived as ‘peripheral’ because there is no centre in a community with respect to the individual’s place in it. This peripherality is ‘legitimate’ because it is legitimated by ‘old-timers’ and, ‘as a place in which one moves toward more-intensive participation, peripherality is an empowering position’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 36). ‘An extended period of legitimate peripherality provides learners with opportunities to make the culture of practice theirs. From a broadly peripheral perspective, [learners] gradually assemble a general idea of what constitutes the practice of the community’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 95). Learning, then, is largely an ‘improvised practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 93). It involves both partaking in the ‘reproduction and transformation of communities of practice’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 55), but also the active construction of (social) identities. Within this framework, how and what advisers learn is never divorced from where they learn. Indeed, expert advisers are part of diverse and dynamic ecosystems of science advice.

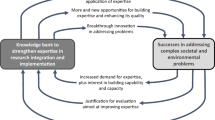

Expert advice as an (evolving) ecosystem

A wealth of research has examined how academia and academics come to influence policy in specific contexts—including a number of articles in this journal (e.g. Cooper, 2016; Kattirtzi, 2016; Gluckman and Wilsdon, 2016; Boswell and Smith, 2017). For Gluckman and Wilsdon (2016), expert advice is best conceived as an (eco)system with no one individual or organisation at the centre of its orchestration. As Gluckman (2016) points out elsewhere, science advice is composed of formal and informal—as well as internal and external—actors and factors. Their constitution and characteristics can differ between countries as well as in relation to different science-related issues. For instance, in the UK, the academic standing and public reputation of individuals are determining factors in the credibility and legitimacy of their advice—more so than in Germany for example (Jasanoff, 2005a; Select Committee on Science and Technology, 2012; Doubleday and Wilsdon, 2012). There are, however, some commonalities in the challenges they face, including: assuring independence and influence, preserving trust while becoming more transparent, and guaranteeing the quality of the advice they provide (Wilsdon, 2014). Today, these ecosystems are more diverse than ever before and yet not quite as resilient as in previous decadesFootnote 10 (as illustrated by the recent culling of advisory bodies in the UK and US, see Curtis, 2010; Goldman, 2019).

Indeed, a number of commentators have expressed concerns about the apparent crisis of science and expertise (e.g. Moore, 2017; Saltelli and Funtowicz, 2017; Bucchi, 2017). Similar arguments have been made about the paradox of increasing reliance on scientific facts and evidence for political decision-making alongside their apparent dismissal and contestation (Pielke, 2007; Bijker et al., 2009). Overall, most commentators agree that the nature of science and of policymaking is changing and, in many ways, needs to change further to meet the so-called Grand Challenges (or ‘wicked problems’) of the 21st century (e.g. Maxwell and Benneworth, 2018). In the UK—despite over 50 years of Government Chief Scientific Advisers (GCSAs)—scientific knowledge is still poorly integrated in most government departments according to the Institute for Government, an eminent British think tank (Sasse and Haddon, 2018). As Sheila Jasanoff (1994) succinctly put it over two decades ago: ‘however rhetorically appealing it may be, no simple formula for injecting expert opinion into policy holds much promise for success’ (p. 17). This holds all the more true for providing expert advice on issues of ‘post-normal science’, wherein ‘the traditional domination of “hard facts” over “soft values” has been inverted’; ‘traditional scientific inputs have become “soft” in the context of the “hard” value commitments’ (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993, pp. 750–751). Environmental and climate issues have typically fallen into that domain (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1994; Hulme, 2009; Gluckman, 2014; Wilsdon, 2014; Saltelli and Funtowicz, 2017).

Nevertheless, I would argue that the ecosystems of expert advice are generally becoming more self-aware in two distinct ways. First, there is increasing awareness that expert advice needs to be tailored to specific and diverse (national) political cultures (Jasanoff, 2005a; Beddington, 2013; Gluckman, 2014; Wilsdon, 2014; SAPEA, 2019; Group of Chief Scientific Advisors, 2019). Second, there is broader acknowledgement that the ‘privilege of science-derived knowledge’ over other knowledge inputs in political decision-making is not always assured or even desirable. Instead, this privilege must be constantly (re)affirmed and (re)negotiated (Gluckman, 2014, 2016; Cooper, 2016; Andrews, 2017; Evans and Cvitanovic, 2018; SAPEA, 2019; Group of Chief Scientific Advisors, 2019). According to Gluckman and Wilsdon (2016), these various changes are already being reflected in the design and practices of new and existing advisory bodies. Advice on science advice is now commonplace in high-impact journals; for example Tyler and Akerlof’s (2019) recent ‘three secrets of survival in science advice’ or Sutherland and Burgman’s (2015) comment on how to ‘use experts wisely’, both published in Nature. In some highly contentious areas, such as climate change, many expert advisers seem to have accepted what social scientists have been saying for a while, namely that political problems can hardly be resolved with technical fixes and that controversies are exacerbated when scientific advice closes off or side-lines certain political conversations (Sarewitz, 2004; Stirling, 2008, 2010; Howe, 2014; Moore, 2017; Blue, 2018). In fact, expert advisers are generally ‘acutely aware’ of the complex web of scientific, political, and ethical considerations in their decision-making (Jasanoff, 1994; Lawton, 2007; Turnpenny et al., 2013). As Jasanoff (2013) asserts: ‘most thoughtful advisers have rejected the facile notion that giving scientific advice is simply a matter of speaking truth to power’ (p. 62). Qualitative research into advisers’ learning can begin to empirically test whether such a statement holds true and in what circumstances. Within this broader agenda for a research programme on advisers’ learning, there are also some more tangible ways in which expert advisers’ knowledge and experiences can contribute to strengthening connections in these ecosystems.

Informing advisers and science-policy organisations

Some of the existing formal guidelines on science advice—such as the Code of Practice for Scientific Advisory Committees in the UK—enact particular configurations of science-policy that are often underpinned by reductive ideas of a linear relationship between science and policymaking, as well as demarcating a strong boundary between them (Palmer et al., 2018). Other guidelines have recognised that this pipeline model of science-policy rarely materialises in practice (e.g. SAPEA, 2019). As illustrated by research from Palmer and colleagues (2018), by turning to advisers’ know-how we can begin not only to make sense of the gap between the (formal) guidelines and realities on the ground, but also to understand why these guidelines need to be there in the first place. With a more explicit focus on advisers’ learning, I believe it is possible to derive some common ‘warning signs’—as opposed to ‘direction signs’—which may be helpful for early-career researchers in particular (see Table 1 for an excellent example of warning signs from John Lawton, in his presidential address to the British Ecological Society). This kind of roadmap would be both open and specific, drawing on individual advisers’ personal narratives, experiences, and anecdotes. This is not to say that the wealth of existing guidelines on science advice should be thrown out of the window. On the contrary, I am simply suggesting another way of testing the robustness of these documents in light of advisers’ own interpretations of their encounters with science-policy. Even though, as Gluckman and Wilsdon (2016) suggest, ‘common principles and guidelines could sit in some tension with a respect for diversity’, I join them in arguing that ‘lessons […] can be transferred sensitively from one context to another’ (p. 3), across generations, disciplines, and career stages. Ideally, we would want to facilitate a two-way exchange between experienced and less experienced advisers, but we may need to settle on a one-way avenue of learning—at the very least for those lessons that get codified in writing.

Given the situated nature of advisers’ learning, qualitative research on advisers’ learning within a given setting can tell us (nearly) as much about the setting as about the advisers’ themselves. On a more superficial level, said research could contribute to the institutional memory of a science-policy organisation, increasing continuity and hence efficiency between predecessors and newcomers. In the case of the British Civil Service, poor institutional memory and high staff turnover means that commissioned research and policy reviews are sometimes lost (Sasse and Haddon, 2018). Altogether, the UK government estimates that ‘wasted effort recreating old work’ costs £500 million/year (Cabinet Office, 2017, p. 9). On a more fundamental level, advisers’ experiences can help shape institutional reform and contribute more generally to organisational learning (see also Pallett and Chilvers, 2015). At either level, one could design an attitude survey with Likert scales, but I maintain that deeper, qualitative methods are likely to throw up more fundamental concerns and questions about the inner politics, governance, and design of science-policy organisations. This matters insofar as advisory bodies are unlikely to remain influential or be resilient to disruptive changes if they are not sufficiently adaptive. As evidenced by Owens’ (2015) work, one of the strengths of the aforementioned Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution was that it learned from its past mishaps and mistakes. Even in the context of more informal or ad hoc advisory capacities, studies of advisers’ learning can prove invaluable and have been largely absent to date. For instance, in its report, the Institute for Government laments the lack of studies on the impact of secondments in government departments (generally of early-career researchers) (Sasse and Haddon, 2018).

Informing research funding organisations

There is another type of organisation, beyond science-policy organisations, that might benefit from scientific advisers’ experiences: research funding organisations. From how science is funded and evaluated, to how science is conducted and validated, academic research has been undergoing its own paradigm shifts in recent years, with an ever-growing focus on innovations for greater connectivity between scientists, practitioners, and decision-makers. These changes have partially emerged from a collective self-reflective exercise. Over the years, influential voices within science, and among social scientists in particular, have made numerous proposals on how the governance and practices of science might be reformed. These have included amongst others: co-design, co-production, and transdisciplinary research with key stakeholders and decision-makers (including, in some cases, policymakers) (van Kerkhoff, 2005; Pohl, 2008; Turnhout et al., 2012, 2020; Rice, 2013; Moser, 2016; Asayama et al., 2019); problem-oriented or Mode-2 research (Gibbons et al., 1994; Gibbons, 1999; Sarewitz, 2017); responsible research and innovation (Owen et al., 2012; Stilgoe et al., 2013); and overall greater openness, public accountability, and democratisation of science and science advice (Funtowicz and Ravetz, 1993; Jasanoff, 1994; Nowotny, 2003; Guston, 2004). Although not all of these proposals have necessarily been realised—in most western democracies—the way research is funded today looks very different from the latter decades of the 20th century. Indeed, ‘a greater onus is being placed on scientists to consider and meet social and ethical demands related to their research’ (Regan and Henchion, 2019, p. 479).

In 2018, British universities got 63% of their research funding from the UK government (mostly through research councils) and 11% from EU sources (including the European Research Council and Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions) (Universities UK, 2018). We can safely assume that at least two-thirds of research funding in the UK is coming from public research councils of various sorts. These research councils have developed their own understanding of ‘impact’ and ‘policy-relevance’. They are key players in both the provision of scientific knowledge to policymakers and in the shaping of research agendas to begin with. Yet many existing guidelines and evaluations of research impact—in the UK and elsewhere—continue to portray relatively ‘linear ideas about how research can be “utilised” to produce more effective policies’ (Boswell and Smith, 2017, p. 2). These implicit (mental) models of how research comes to influence policymaking may be, for many researchers, the main basis of their own mental models. As illustrated by the huge strides they have made in stimulating and incentivising greater relevance and impact of research for policymaking, UK-based research councils are well aware of that.

In the UK context, some commentators have suggested that they have not gone far enough (e.g. Tyler, 2017) and there are discussions around the next iteration of the Research Excellence Framework (REF) beyond 2021 (see Weinstein et al., 2019 for a pilot study on attitudes towards REF 2021). The REF determines the allocation of a portion of public funding to British universities and affects these universities’ ranking in league tables. The current definition of ‘impact’ for REF 2021 is: ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia’ (REF, 2019a, p. 90). Impact case studies submitted by universities are given a ranking. One of the criteria for achieving a four-star ranking (highest) is the potential for ‘major changes in policy or practice’ (REF, 2019b, p. 36). In its rationale for investing in research, UK Research and Innovation (UKRI)—the conglomerate organisation containing all the research councils—claims that it drives innovation in ‘intelligence for policymaking’. In the US, all proposals submitted to the National Science Foundation (NSF) are also evaluated for their ‘broader impacts’, defined as ‘the potential to benefit society and contribute to the achievement of specific, desired societal outcomes’ (NSF, 2014, p. 3). Impact also plays a key role in the scoring of proposals submitted to EU funding institutions (European Commission’s various Frameworks programmes, European Research Council, and so on).

We can clearly see that, in the European, British and US contexts, research funding bodies’ definition of (policy) impact play an important role in both determining what constitutes good research, but also ultimately in deciding what research proposals have potential for impact to begin with. In both instances, I argue that the experiences of advisers can be informative. This is in fact very much in line with the argument that Cooper (2016) puts forward in saying that Chief Scientific Advisers should influence research agendas to be more policy-relevant or ‘policy-oriented’. I argue that expert advisers are particularly well placed to understand the policy-relevance of research. They could play a key role in the governance of science, in policy for science. If they initially held a linear view of academia’s role in politics and policy—wherein scientific facts comes to inform political decisions in a linear fashion—they have often had to adjust this view in the face of experienced realities as advisers. They retain an experience of the ‘political economy of science governance’ (Stilgoe et al., 2013), with its very many particularities and quirks. From that angle, their experiences as advisers become valuable in translating the wants of policymakers, and the determinants of impact, into refinements of existing impact evaluation frameworks for research funding. In such circumstances, science advisers could more systematically be consulted by research funding agencies in the formulation of their policies, especially in relation to research impact.

Subsequent changes to impact evaluation frameworks would be most significant for early-career researchers who are still working out their niche in the broader academic job market. If early-career researchers are going to base their understanding of impact in large part on the existing guidelines for grant applications or job descriptions, then they are in danger of seeing the relationship between science and policy as objectively and normatively linear. In line with my earlier argument about early-career researchers wishing to engage with policy, I would argue that the lessons of experienced advisers applied to impact evaluation frameworks for research funding can have positive trickle-down effects on how early-career researchers choose to frame and conduct their research. In my own experience applying for PhD funding with the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), it was not clear how best to align my research proposal with the ESRC’s broader impact objectives (organised in clusters). In my case, it was a bit of a stab in the dark. I wished to find more helpful guidance from which the whole academic community would benefit.

Conclusions and way forward

Throughout this paper, I have argued that scientific advisers’ personal experiences of advising deserve more scholarly attention. Expert advisers are particularly well positioned to comment on the state of science-policy, on the various challenges and rewards in taking up the role of adviser, and on the evaluation of ‘impact’ in the modern academy. The knowledge of experienced advisers, I argue, can be particularly useful for early-career researchers who want to see their research transcend immediate academic circles. And even for those early-career and mid-career researchers who are principally striving to make their mark in academia, evaluations of (policy) impact are here to stayFootnote 11. As the worlds of both science and policy continue to undergo transformations within—and in their relation to one another—a closer look at individual advisers’ transformations can be one actionable way of navigating the complexity of these systemic changes and understand how individuals are responding to them. In the same way that history in a science-policy context can prove invaluable in learning from past mistakes on a macro-level (Higgitt and Wilsdon, 2013), so too can qualitative studies of individual advisers’ learning on a micro-level.

In carrying out such a research programme—from a more sociological point of view—triangulating different methods might increase the chances of capturing processes of learning, both a posteriori and in situ. Of the different methods that social scientists can use, in-depth and open-ended interviews can go some way in inducing research participants to (critically) reflect on their past experiences engaging with policymaking. More structured interviews or surveys run the risk of overlooking the importance of the oral histories and memorable anecdotes in their recollection of learning. They also tend to afford less room for the research participants to assign their own significance to some events or aspects of learning over others. The ‘nondirective interview’—originally developed by the American humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers—is particularly meritorious, as it consists of ‘mirroring back’ the interviewees responses to questions, encouraging the interviewee to be more self-reflective and allowing ‘the interviewee, rather than the interviewer, to assign significance to the topics covered in the interview’ (Lee, 2011, p. 126). The interviewer is then relegated to the role of facilitator and must actively subscribe to a non-judgemental and accepting attitude vis-à-vis the interviewee (Michelat, 1975; Mahoney and Baker, 2002). The nondirective interview can ‘soften the effects of social distance between interviewer and interviewee’ (Lee, 2011, p. 135) and gives experts, in particular, ‘the room… to unfold [their] own outlooks and reflections’ (Meuser and Nagel, 2009, p. 31), possibly granting the interviewer greater access to their inner experience.

When it comes to studying the situated nature of advisers’ learning, ethnographic methods could go some way in apprehending and analysing the organisational cultures of expert advice, the interactions individual advisers have with their peers, and the various forms that advice can take. Institutional ethnography (see Smith, 1987; Devault, 2006), organisational ethnography (see Ciuk et al., 2018), or an ‘ethnography of meeting’ (see Brown et al., 2017) can provide ‘thick descriptions’ of organisations and the work that occurs within them—constantly problematising the mundane and the banal. Indeed, as Brown and colleagues (2017) point out, meetings can be seen as ‘boringly, even achingly, familiar routines, including ordinary forms of bureaucratic conduct’, yet they are equally ‘specific and productive arenas in which realities are dramatically negotiated’ (p. 11). While these kinds of ethnography—in isolation—do not necessarily grant researchers greater access to research participants’ inner thoughts and feelings, they remain invaluable tools in examining the institutional environments within which expert advisers evolve. Moreover, although attempts to generalise across different political cultures of science advice (or even individual committees) may be deeply flawed and even undesirable, the seminal work by Sheila Jasanoff on ‘civic epistemologies’Footnote 12 (see Jasanoff, 2005b) has shown that meaningful and rich comparisons can nonetheless be drawn between systems of science advice. To that end, a multi-sited ethnography could begin to shed light on important similarities and differences across these systems of advice and their various sites.

One other method which might be particularly rewarding is the unstructured or semi-structured diary. As Furness and Garrud (2010) demonstrate, ‘unstructured diaries are often kept as a personal response to times of change, upheaval, and exploration, and also provide interesting information about routine and trivial life experiences’ (p. 263). They can provide longitudinal data, minimise recall bias, provide ‘thick’ descriptions and interpretations of real-life events, and they work well in conjunction with other methods (Furness and Garrud, 2010). I should emphasise that while none of these methods will generate exhaustive accounts of individual advisers’ learning, by bringing them together we can begin to paint a clearer picture of their lived experienced and the environmental factors that influence it. I should also acknowledge a few key challenges I have identified in pursuing this kind of research. One is the inherent difficulty of extracting and abstracting the tacit, experiential knowledge and moments of learning from the explicit, transferable lessons of advisers. Indeed, much of the knowledge of particular policy areas, including administrative and legal practices, is tacit (Parker, 2013). Another challenge is largely methodological: what are the methods that would best capture advisers’ learning? How does one deal with research participants who seem to be avoiding critical introspection? In fact, their learning could well have been more superficial and instrumental than deep and open-ended.

In approaching these various research dilemmas, one of my points of departure is a general agnosticism (where possible) towards the normative aspects of their learning (e.g. are they doing it for the right reasons?). That is not to say that questions about advisers’ motivations should not feature in interviews, for example, but rather that the initial value judgements of those motivations should first and foremost come from the research participants rather than the researcher. As I discussed in relation to nondirective interviewing, such agnosticism on the part of the researcher may be necessary for greater access to advisers’ inner thoughts and feelings. Although approaches that adopt more critical or strategically antagonistic stances with respect to experts’ learning in science-policy could be fruitful, I would contend that we first need to develop and test a range of empirical tools for studying advisers’ learning, a task that requires a certain amount of agnostic experimentation, as well as inputs from a variety of disciplinary perspectives and geographies. Indeed, I have approached this research programme through my own spectrum and training—largely drawing on literature in the social studies of science and on UK-centric examples. I hope those very limitations stimulate a diversity of researchers (especially in the non-western world) to take up and challenge the ideas presented in this paper.

Data availability

No new data was generated or analysed for this paper.

Notes

Can be found under decision IPBES-7/1, section II(b), in the report of the 7th Plenary: https://www.ipbes.net/system/tdf/decision_ipbes-7_1_en_adv.pdf?file=1&type=node&id=35304. Acessed 28 Aug 2019.

While Mezirow’s original theory was about individuals only, there is nonetheless evidence that he was inspired by Thomas Kuhn’s work (Kitchenham, 2008).

In this paper, ‘science’ is understood as its German counterpart Wissenschaft—defined as the ‘systematic enquiry that aims to produce reliable knowledge’ (Brown, 2017, p. 5)—and hence includes the social sciences and the humanities.

‘Science advice’ and ‘expert advice’ are used interchangeably throughout the commentary.

In British English, an ‘encounter’ is often evocative of an unexpected or difficult meeting with people, objects, or situations. It can be adversarial or intimate. It is therefore—in my view—a fitting term to describe the experience of experts engaging in the business of advice-giving.

I am partly referring to David Guston’s concept of ‘boundary organisation’ (Guston, 2001).

I am referring to Thomas Gieryn’s concept of ‘boundary work’ (Gieryn, 1983).

By resilience, I mean the capacity of advisory bodies to survive through successive political administrations and/or through various policy transitions and upheavals. Scholars have identified a number of factors which contribute to advisory bodies’ resilience. They have included their ability to facilitate communication between scientists and policymakers without overstepping boundaries (Boswell, 2018), maintain a diverse membership (Owens, 2015), and sustain trust from policymakers and the public alike (Grove-White, 2001; Gluckman, 2014; Andrews, 2017; SAPEA, 2019; Group of Chief Scientific Advisors, 2019).

It should be noted that the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) recently axed their ‘Pathways to Impact’ form, which was previously a requirement for research funding applications submitted to the various British Research Councils.

In Designs on Nature: Science and Democracy in Europe and the United States, Sheila Jasanoff (2005b) argues that different (national) political cultures have particular civic epistemologies: ‘institutionalised practices by which members of a given society test and deploy knowledge claims used as a basis for making collective choices’ (p. 272). In her comparison of the UK, the US and Germany, Jasanoff (2005b) identifies three different civic epistemologies, namely: communitarian, contentious, and consensus-seeking. One distinctive characteristic that Jasanoff (2005b) associates with a British civic epistemology, for example, is the importance of the individual adviser’s academic and public credentials—and hence trustworthiness—as opposed to their institutional affiliations (which matter most in Germany).

References

Andrews L (2017) How can we demonstrate the public value of evidence-based policy making when government ministers declare that the people ‘have had enough of experts’? Palgrave Commun 3:11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0013-4

Armitage D, Marschke M, Plummer R (2008) Adaptive co-management and the paradox of learning. Glob Environ Change 18:86–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2007.07.002

Asayama S, Sugiyama M, Ishii A, Kosugi T (2019) Beyond solutionist science for the Anthropocene: to navigate the contentious atmosphere of solar geoengineering. Anthropol Rev 2053019619843678. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019619843678

Beddington J (2013) The science and art of effective advice. In: Doubleday R, Wilsdon J (eds) Future directions for scientific advice in Whitehall. Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP), Cambridge, pp. 22–31

Bijker WE, Bal R, Hendriks R (2009) The paradox of scientific authority: the role of scientific advice in democracies. MIT Press, Cambridge

Blue G (2018) Scientism: a problem at the heart of formal public engagement with climate change. ACME Int J Crit Geogr 17(2):544–560

Boswell C, Smith K (2017) Rethinking policy ‘impact’: four models of research-policy relations. Palgrave Commun 3:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-017-0042-z

Boswell J (2018) Keeping expertise in its place: understanding arm’s-length bodies as boundary organisations. Policy Polit 46:485–501. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557317X15052303355719

Brown MB (2017) Not everything political is politics. Public Seminar. http://www.publicseminar.org/2017/06/not-everything-political-is-politics/. Accessed 20 Feb 2019

Brown H, Reed A, Yarrow T (2017) Introduction: towards an ethnography of meeting. J R Anthropol Inst 23:10–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9655.12591

Bucchi M (2017) Credibility, expertise and the challenges of science communication 2.0. Public Underst Sci 26:890–893. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517733368

Budwig N (2015) Concepts and tools from the learning sciences for linking research, teaching and practice around sustainability issues. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 16:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.003

Cabinet Office (2017) Better information for better government. Cabinet Office Digital Records and Information Management Team, working in collaboration with the National Archives and Government Digital Service

Cash DW, Clark WC, Alcock F et al. (2003) Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:8086–8091. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1231332100

Ciuk S, Koning J, Kostera M (2018) Organizational ethnographies. In: Cassell C, Cunliffe A, Grandy G (eds) The SAGE handbook of qualitative business and management research methods: history and traditions. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, UK, pp. 270–285

Cooper AC (2016) Exploring the scope of science advice: social sciences in the UK government. Palgrave Commun 2:16044. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.44

Curtis P (2010) Government scraps 192 quangos. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2010/oct/14/government-to-reveal-which-quangos-will-be-scrapped

Devault ML (2006) Introduction: what is institutional ethnography? Soc Probl 53:294–298. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2006.53.3.294

Doubleday R, Wilsdon J (2012) Science policy: beyond the great and good. Nature 485:301–302. https://doi.org/10.1038/485301a

Dunlop CA (2009) Policy transfer as learning: capturing variation in what decision-makers learn from epistemic communities. Policy Stud 30:289–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870902863869

Evans MC, Cvitanovic C (2018) An introduction to achieving policy impact for early career researchers. Palgrave Commun 4:88. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0144-2

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR (1993) Science for the post-normal age. Futures 25:739–755. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-3287(93)90022-L

Funtowicz SO, Ravetz JR (1994) Uncertainty, complexity and post-normal science. Environ Toxicol Chem 13:1881–1885. https://doi.org/10.1002/etc.5620131203

Furness PJ, Garrud P (2010) Adaptation after facial surgery: using the diary as a research tool. Qual Health Res 20:262–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309357571

Gibbons M (1999) Science’s new social contract with society. Nature 402:C81–C84. https://doi.org/10.1038/35011576

Gibbons M, Limoges C, Nowotny H, et al. (1994) The new production of knowledge: the dynamics of science and research in contemporary societies, 1st edn. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi

Gieryn TF (1983) Boundary-work and the demarcation of science from non-science: strains and interests in professional ideologies of scientists. Am Sociol Rev 48:781. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095325

Gluckman P (2014) Policy: the art of science advice to government. Nat News 507:163

Gluckman P (2016) The science–policy interface. Science 353:969

Gluckman P, Wilsdon J (2016) From paradox to principles: where next for scientific advice to governments? Palgrave Commun 2:16077. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.77

Goldman GT (2019) Trump’s plan would make government stupid. Nature 570:417. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-01961-6

Group of Chief Scientific Advisors (2019) Scientific advice to European Policy in a complex world. European Commission, Directorate-General for Research and Innovation, Brussels

Grove-White R (2001) New wine, old bottles? Personal reflections on the New Biotechnology Commissions. Polit Q 72:466–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.00426

Guston DH (2001) Boundary organizations in environmental policy and science: an introduction. Sci Technol Hum Values 26:399–408

Guston DH (2004) Forget politicizing science. Let’s democratize science! Issues Sci Technol 21:25–28

Higgitt R, Wilsdon J (2013) The benefits of hindsight: how history can contribute to science policy. In: Doubleday R, Wilsdon J (eds) Future directions for scientific advice in Whitehall. Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP), Cambridge, pp. 22–31

Howe JP (2014) Behind the curve: science and the politics of global warming. University of Washington Press

Hulme M (2009) Why we disagree about climate change: understanding controversy, inaction and opportunity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge; New York

Jasanoff S (1994) The Fifth Branch: science advisers as policymakers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Jasanoff S (2005a) Judgment under siege: the three-body problem of expert legitimacy. In: Maasen S, Weingart P (eds) Democratization of expertise? Exploring novel forms of scientific advice in political decision-making. Springer, Netherlands, Dordrecht, pp. 209–224

Jasanoff S (2005b) Designs on nature: science and democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Jasanoff S (2013) The science of science advice. In: Doubleday R, Wilsdon J (eds) Future directions for scientific advice in Whitehall. Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP), Cambridge, pp. 62–68

Kattirtzi M (2016) Providing a “challenge function”: Government social researchers in the UK’s Department of Energy and Climate Change (2010–2015). Palgrave Commun 2:16064. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.64

Kitchenham A (2008) The evolution of John Mezirow’s transformative learning theory. J Transform Educ 6:104–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344608322678

König A (2015) Changing requisites to universities in the 21st century: organizing for transformative sustainability science for systemic change. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 16:105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2015.08.011

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Lawton JH (2007) Ecology, politics and policy. J Appl Ecol 44:465–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2007.01315.x

Lee RM (2011) “The most important technique …”: Carl Rogers, Hawthorne, and the rise and fall of nondirective interviewing in sociology. J Hist Behav Sci 47:123–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbs.20492

Mahoney KT, Baker DB (2002) Elton Mayo and Carl Rogers: a tale of two techniques. J Vocat Behav 60:437–450. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1839

Maxwell K, Benneworth P (2018) The construction of new scientific norms for solving Grand Challenges. Palgrave Commun 4:52. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0105-9

Meuser M, Nagel U (2009) The expert interview and changes in knowledge production. In: Bogner A, Littig B, Menz W (eds) Interviewing experts. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 17–42

Mezirow J (1978) Education for perspective transformation: women’s re-entry programs in community colleges. Center for Adult Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, New York

Mezirow J (1995) Transformation theory of adult learning. In: Welton MR (ed) In defense of the lifeworld: critical perspectives on adult learning. State University of New York Press, New York, pp. 39–70

Mezirow J, Associates (2000) Learning as transformation: critical perspectives on a theory in progress, 1st edn. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco

Michelat G (1975) Sur l’utilisation de l’entretien non directif en sociologie. Rev Fr Sociol 16:229–247. https://doi.org/10.2307/3321036

Moore AJ (2017) Critical elitism: deliberation, democracy, and the problem of expertise, 1st edn. Cambridge University Press, New York

Moser SC (2016) Can science on transformation transform science? Lessons from co-design. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 20:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.10.007

Nowotny H (2003) Democratising expertise and socially robust knowledge. Sci Public Policy 30:151–156. https://doi.org/10.3152/147154303781780461

NSF (2014) Perspectives on broader impact. National Science Foundation

Owen R, Macnaghten P, Stilgoe J (2012) Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Sci Public Policy 39:751–760. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs093

Owens S (2015) Knowledge, policy, and expertise: the UK royal commission on environmental pollution 1970-2011. Oxford University, New York

Pallett H, Chilvers J (2015) Organizations in the making: learning and intervening at the science–policy interface. Prog Hum Geogr 39:146–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132513518831

Palmer J, Owens S, Doubleday R (2018) Perfecting the ‘elevator pitch”? Expert advice as locally-situated boundary work. Sci Public Policy scy054 https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scy054

Parker M (2013) Making the most of scientists and engineers in government. In: Doubleday R, Wilsdon J (eds) Future directions for scientific advice in Whitehall. Centre for Science and Policy (CSaP), Cambridge, pp. 49–55

Pielke RA (2007) The honest broker: making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, New York

Pohl C (2008) From science to policy through transdisciplinary research. Environ Sci Policy 11:46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2007.06.001

Porter JJ, Dessai S (2017) Mini-me: why do climate scientists’ misunderstand users and their needs? Environ Sci Policy 77:9–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.004

REF (2019a) Guidance on submissions. Research Excellence Framework

REF (2019b) Panel criteria and working methods. Research Excellence Framework

Regan Á, Henchion M (2019) Making sense of altmetrics: the perceived threats and opportunities for academic identity. Sci Public Policy 46:479–489. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scz001

Rice M (2013) Spanning disciplinary, sectoral and international boundaries: a sea change towards transdisciplinary global environmental change research? Curr Opin Environ Sustain 5:409–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2013.06.007

Saltelli A, Funtowicz S (2017) What is science’s crisis really about? Futures 91:5–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2017.05.010

SAPEA (2019) Making sense of science for policy under conditions of complexity and uncertainty. Science Advice for Policy by European Academies (SAPEA), Berlin

Sarewitz D (2004) How science makes environmental controversies worse. Environ Sci Policy 7:385–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2004.06.001

Sarewitz D (2017) Kill the myth of the miracle machine. Nature 547:139–139. https://doi.org/10.1038/547139a

Sarewitz D, Pielke RA (2007) The neglected heart of science policy: reconciling supply of and demand for science. Environ Sci Policy 10:5–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2006.10.001

Sasse T, Haddon C (2018) How government can work with academia. Institute for Government, London

Scoones I, Stirling A, Abrol D et al. (2020) Transformations to sustainability: combining structural, systemic and enabling approaches. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.12.004

Select Committee on Science and Technology (2012) The role and functions of departmental Chief Scientific Advisers. Authority of the House of Lords, London. TSO

Selin NE, Stokes LC, Susskind LE (2017) The need to build policy literacy into climate science education. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 8:e455. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.455

Smith DE (1987) The everyday world as problematic: a feminist sociology. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Spruijt P, Knol AB, Vasileiadou E et al. (2014) Roles of scientists as policy advisers on complex issues: a literature review. Environ Sci Policy 40:16–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2014.03.002

Stilgoe J, Owen R, Macnaghten P (2013) Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res Policy 42:1568–1580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.05.008

Stirling A (2008) “Opening up” and “closing down”: power, participation, and pluralism in the social appraisal of technology. Sci Technol Hum Values 33:262–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0162243907311265

Stirling A (2010) Keep it complex. Nature 468:1029–1031. https://doi.org/10.1038/4681029a

Sutherland WJ, Burgman M (2015) Policy advice: use experts wisely. Nat News 526:317. https://doi.org/10.1038/526317a

Turnhout E, Bloomfield B, Hulme M et al. (2012) Conservation policy: listen to the voices of experience. Nature 488:454–455. https://doi.org/10.1038/488454a

Turnhout E, Metze T, Wyborn C et al. (2020) The politics of co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 42:15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2019.11.009

Turnhout E, Stuiver M, Klostermann J et al. (2013) New roles of science in society: different repertoires of knowledge brokering. Sci Public Policy 40:354–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs114

Turnpenny J, Russel D, Rayner T (2013) The complexity of evidence for sustainable development policy: analysing the boundary work of the UK Parliamentary Environmental Audit Committee. Trans Inst Br Geogr 38:586–598. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00549.x

Tyler C (2017) Wanted: academics wise to the needs of government. Nature 552:7. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-017-07744-1

Tyler C, Akerlof K (2019) Three secrets of survival in science advice. Nature 566:175. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00518-x

Universities UK (2018) Higher education in facts and figures 2018. Universities UK, London

van Kerkhoff L (2005) Integrated research: concepts of connection in environmental science and policy. Environ Sci Policy 8:452–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2005.06.002

Wals AEJ (ed) (2009) Social learning towards a sustainable world: principles, perspectives, and praxis, Reprint. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen

Weinstein N, Wilsdon J, Chubb J, Haddock G (2019) The real time REF review: a pilot study to examine the feasibility of a longitudinal evaluation of perceptions and attitudes towards REF 2021. Research England

Wenger-Trayner E, Wenger-Trayner B (2015) Introduction to communities of practice: a brief overview of the concept and its uses. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/. Accessed 10 Jun 2019

Wilsdon J (2014) The past, present and future of the Chief Scientific Advisor. Eur J Risk Regul 5:293–299. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1867299X00003809

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for the scholarship provided by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) Doctoral Training Partnership at the University of Cambridge, without which this work would not have been possible. I am also indebted to my supervisor, Professor Mike Hulme, for supporting and guiding me through my PhD journey. A huge thanks to Shin Asayama for his ongoing support and constructive feedback. Finally, thank you to Emilia Ochoa, David Durand-Delacre, Maximilian Gregor Hepach, and Elliot Honeybun-Arnolda for their comments and encouragement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Obermeister, N. Tapping into science advisers’ learning. Palgrave Commun 6, 74 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0462-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0462-z