Abstract

This article analyses the role of different types of social capital in the integration of immigrants into the labour market of Catalonia (Spain), according to the geographical distribution and ethnic characteristics of immigrants’ contacts. It aims to test the role of social networks, human capital and the ethno-stratification of the labour market in immigrants’ labour market performance; and to contribute to understanding the often overlooked but complex interactions between these factors and gender inequalities. Results show that transnational ties constitute a weak resource in obtaining job benefits, that labour-intensive ethnic occupational niches confine immigrants to low-skilled positions to a great extent and that, even controlling for human capital and industrial sectors, having supportive links with native-born Spaniards has a positive effect on migrants’ occupational status. Finally, gendered differences are also evident in respect of returns on social capital, indicating that the sexually segregated occupational structure of the Spanish labour market makes social capital a weaker resource for women immigrants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the Global North migrants’ working lives are routinely defined by the precarity of employment at the bottom of the labour market (Lewis et al., 2015). As a result, they usually face indecent working and living conditions and major vulnerability to economic recessions (ILO, 2012). In Spain, Moroccan and Ecuadorian immigrants are among the most disadvantaged ethnic groups in the occupational structure, with the lowest wages and the worst contractual conditions (Miguélez et al., 2011). These disadvantages, moreover, intersect with gender inequalities, restricting immigrant women’s options in a gendered labour market that reinforces their entrapment in its lowest positions (Parella, 2003). How are these phenomena explained?

Two main approaches have been used to explain immigrants’ disadvantage and ethnic inequalities in the labour market. First, human capital theory treats work as just another tradeable market commodity adjusted through the equilibrium between the supply and demand for labour. In the market, employees’ investments in education and training are rewarded by employers because of the higher productivity that they offer (Degenne and Forsé, 1999). From this perspective, inequalities in the labour market are explained mostly by differences in the individual’s decision to invest in education and training (Becker, 1983). In the case of migrants, Chiswick (1978) also considers the international transferability of human capital skills, namely language, job-related skills, labour market information, and credentials. These factors are expected to increase as time passes in the destination, therefore drawing a U-shaped pattern of occupational change over time in the host country (Chiswick et al., 2003).

Secondly, labour market stratification theory rejects the assumption that labour market divisions can be attributed mainly to inadequate levels of human capital or differences in productivity. Following some of the long-standing critiques of human capital theory (see Bowles and Gintis, 1975), labour market stratification theory claims that the concept perpetuates an overly simplistic view of the labour market based on individual choices and market rewards that end up blaming the victim, that is, those who are unsuccessful in the labour market. This approach, by contrast, highlights the role of the structure of labour demand instead. It considers that inequalities are fostered mainly through both formally and informally institutionalized policies and practices in labour markets and workplaces (Grimshaw et al., 2017). Labour market stratification theory also believes that, as a result, the labour market is divided into different segments with different structures and characteristics. On the one hand, a primary segment with high levels of security and stability, possibilities for promotion and prestigious jobs. On the other hand, a secondary segment with low wages, job instability, bad working conditions and a lack of career prospects (Piore, 1975; Grimshaw et al., 2017).

According to the labour market stratification theory, the labour market is stratified along ethnic lines in a way that pushes immigrants to occupy positions in the secondary segment, specifically in employment nichesFootnote 1 (Pajares, 2005; Miguélez et al., 2011). This theory acknowledges that transnational migrant processes and processes of exclusion practised by states often close down real and acceptable alternatives for migrants to engage in precarious and exploitative labour (Lewis et al., 2015). In Spain, in particular, the growth of immigration has both enabled and been promoted by the economic expansion of some labour-intensive industrial sectors. This process has been reinforced by Spanish migration policies by facilitating the placement of immigrants in ‘hard-to-fill jobs’ (that local workers are less inclined to do), and more broadly by creating a ‘discriminatory institutional framework’ that restricts access to residence and work permits, and places barriers to the recognition of academic titles (Cachón, 2009; Veira et al., 2011), particularly to immigrants from the Global South. It all contributes to placing such labour-intensive industrial sectors in the secondary labour market, characterized by low wages, limited contractual security, and little stability or possibilities for promotion (Martinez Veiga, 1997; Miguélez et al., 2011). These sectors have thus become ethnic occupational niches in which the jobs on offer are arduous, dangerous and precarious (Cachón, 2003, p. 38), ones rejected by the autochthonous population (Parella, 2003) and often situated in the informal economy (Pajares, 2005). Diverse mechanisms of ethnic and/or racial discrimination by employers and society as a whole contribute to binding immigrants within these sectors, with some occupations coming to be regarded as ‘immigrants’ jobs’ (Cachón, 2003; Parella, 2012). In Spain these ethnic occupational niches include construction, agriculture, hotels and catering, retail and domestic work (Pajares, 2010).

Finally, the labour market stratification theory also highlights the fact that concentration in a few employment sectors is even stronger for immigrant working women. In the context of a sexually segregated occupational structure, immigrant women also face gendered discrimination in their access to paid work that relegates them to the employment niches that Spanish women reject (Parella, 2003, p. 138). The growing influx of female migration has been closely linked to the expansion of the service sector, the mercantilisation of care (Parella, 2003) and the subsequent growth of employment opportunities in hotels, catering and particularly domestic work (Moreno-Colom and López-Roldán, 2018). As a result, immigrant women’s employment is strongly bounded by or concentrated in stigmatized employment niches, in positions that are unqualified, undervalued, and have markedly servile connotations (Moreno-Colom and López-Roldán, 2018).

There is also a third fertile stream of literature, which emphasizes the importance of seeking jobs through social networks in enabling individuals to access certain positions in the labour market (Granovetter, 1973, 1974; Lin, 1999). The social network perspective on the labour-market integration of migrants does not fit clearly into either of the two previous approaches. Indeed, this perspective makes a clear criticism of the human capital approach, as it recognizes that information on job opportunities does not flow properly on the labour market, stressing that mechanisms other than investment in education and training explain how jobs are obtained. In this sense, social network analysis points to the fact that individualistic models are insufficient to explain labour market performance because the social context can strongly alter the links between individual capacities and motivations and the expected rewards (Lin, 1999; Portes and Rumbaut, 2010). By so doing, the premises of many network explanations of incorporation into the labour market challenge the liberal view of this process. However, such network explanations usually assume that the professional environment is unstructured and unsegmented (Degenne and Forsé, 1999, p. 114) and tend to ignore the broader institutional framework within which immigrant employment occurs (Waldinger, 1994, p. 4). Very little work has been conducted that takes into account the interplay between on the one hand the structure of opportunities on the demand side, and on the other hand immigrants’ resources (Kloosterman and Rath, 2010).

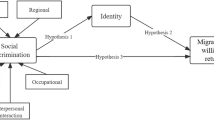

This article aims to fill this gap by assessing the type of social capital that is most useful for status attainment by immigrants in Spain, given both their human capital and the segmented and ethno-stratified context in which social networks operate. More specifically, it aims to identify what is the most resourceful type of social capital (supportive contacts with the autochthonous population, with co-ethnics living in the country of origin or with co-ethnics living in Spain) for immigrant men and women, who experience (or suffer) the immigrant concentration in the labour market in different ways.

In the next section, the article delves into the literature on immigrant networks and labour market performance. The following methods section presents the network-based methodology adopted here. A personal network survey of 150 Ecuadorian and Moroccan immigrants living in Catalonia, Spain, was carried out using questionnaires on personal networks that retrieved the network of the 30 ‘closest’ contacts for every interviewee. The “Results” section presents the logistic regression analysis that was subsequently performed, showing the relevance of both social capital and the ethno-stratified and gendered structure of the labour market. To conclude, the article reflects on the results obtained in light of the various theoretical debates.

Social networks and labour market attainment

Social networks, defined as social interactions among individuals, are treated as operational and conceptual frameworks that emphasize the relational aspects of social reality and conceptualize social life in terms of the structures of relationships among actors (Carrington and Scott, 2011, p. 6). This perspective takes into account the meso-social dimension of the social structure that provides resources (material, symbolic, informational, etc.) to the agents involved in these networks, thereby both creating and constraining opportunities for action for the individuals embedded in them (Bottero and Crossley, 2011; Bolíbar, 2016). In this sense, following the approach of Bourdieu (1986), Coleman (1988) and Lin (1999), the network of personal relationships may be regarded as the structure where social capital is created, expressed and distributed (Lozares et al., 2011).

Among immigrants, the patterns and structures of informal sociability both reflect and influence the diversity of individual integration processes (Lubbers et al., 2010). Personal networks reveal personal communitiesFootnote 2 (Wellman, 1979; Chua et al., 2011) and express the diversity of individual settlement processes, as they show the different ways in which migrants cut old links with their countries of origin and create new links in their host countries with different kinds of people (Molina et al., 2008; Bolibar et al., 2015). In the empirical study of transnational movements and migratory processes, social networks have been identified as an important resource for migrants’ incorporation into the host society, and consequently as a key element in the process of settlement and social integration (Massey et al., 1993; Portes, 1998; Maya-Jariego, 2001; Cheong et al., 2007; Molina et al., 2008; Lubbers et al., 2010; De Miguel and Tranmer, 2010).

Research focusing in particular on the role of social capital in labour market performance goes back to Granovetter’s seminal research on the strength of weak ties, which pointed out the particular relevance of links to people with no common friends in obtaining new and valuable information on job opportunities. This study opened up a fertile stream of research on the use of contacts in seeking and finding employment, as well as in hiring, recruiting and training. The application of these premises to immigrants’ labour market performance has shown the importance of social networks and social capital in defining the possibilities of migrants being promoted inside a firm (Behtoui and Neergaard, 2010), in determining wage rates (Aguilera and Massey, 2003) and in identifying the sectors in which they are employed (Livingston, 2006). In these regards, there is a debate about what kinds of ties are more useful for immigrants in their endeavours to make progress in the labour market.

Some research points to ties with autochthonous populations as the most valuable for immigrants to succeed in the labour market by attaining a higher employment and occupational status, as by building bridges to the native population such networks span structural holes (Lancee, 2010) that bridge ethnic divides, which are usually also associated with socioeconomic distinctions (Lancee, 2012). In this sense, Lin in particular developed his theory of the strength of position, pointing to the fact that access to and the mobilization of resources embedded in networks, as well as the outcomes of such mobilization in the labour market, depend on the socioeconomic status of personal contacts (1999).

On the other hand, the structure and vitality of ties within immigrant communities that determine immigrants’ ‘reception contexts’ have also been used to explain differences between ethnic groups in their positioning in the structure of labour (Portes and Rumbaut, 2010). Along these lines, Portes and Rumbaut argue that the differential performance between, for example, Mexican and Cuban migrants in the American labour market is not necessarily due to their respective abilities but to the wealth and strength of their community networks, that is, to the resources that are exchanged by means of these networks and the economic organization of ethnic enclaves so as to promote opportunities for mobility through ethnic labour niches in an entirely network-driven way (Portes, 1998, p. 13). Sanders et al. (2002) also identify a negative relation between co-ethnic networks and upward occupational mobility among Asian immigrants in Los Angeles. Other researchers, however, point to the ‘negative effects of social capital’ (Portes, 1998) at work within ethnic-enclaved networks. They might work to concentrate the immigrant workforce within ethnic occupational niches, as the exchange of solidarity and information through social networks might pull migrants into the same situation as their fellow countrymen (Martinez Veiga, 1997). In this sense, the immigrant niche might be a product of the repeated interaction of the networks that link immigrant newcomers to more established compatriots and settle them in those places where their compatriots are already established (Waldinger, 2001; Schrover et al., 2007).

Finally, more recent research rooted in the transnational approach to the migration phenomenon points to the fact that immigrants’ networks are scattered throughout the globe, producing and reproducing transnational social fields in which resources are exchanged in a de-territorialized manner (Levitt and Glick-Schiller, 2004; Vertovec, 2009). Taking this into account, some researchers have also pointed to the value of these transnational ties as a source of business and professional success (Gold, 2001; Kloosterman and Rath, 2010), as they enable the mobilization of resources from different contexts on a global scale.

On top of these three approaches, other developments in the literature have suggested that, in different cultural contexts and in different job categories, factors such as personal reputation or peer-group status may change the kind of ties that different kinds of workers prefer (Degenne and Forsé, 1999). In this regard, the notion of intersectionality can help to explain how social networks often tend to reflect and perpetuate the existing structural inequalities and power relations in a society. Networks may have a different value for different individuals at different times and for different purposes, depending on their social location in the mainstream hierarchical order (Anthias, 2007). In other words, the social valuation of population categories (such as ‘women’ or ‘migrants’) and their articulation or interrelation (e.g., ‘migrant women’), both within a minority ethnic context and within the wider society, can affect the value of their relational resources as well as their ability to use them to create economic capital (Anthias, 2007, 2012). Following these approaches, research has shown that the likelihood of finding a good job as a result of one’s social capital varies along gender and ethnic lines because of the impact of axes of inequality on the capacity to obtain both beneficial information and influential contacts (Trimble and Kmec, 2011, p. 170; Livingston, 2006). Networks are different in form and function for immigrant men and women, as their migration patterns, timing of and reasons for their migration are different, and they are differently embedded in the family sphere (Schover et al., 2007; Bolíbar, 2016). Thus, networks might operate in gendered ways to produce systematic differences in labour market outcomes for men and women immigrants, respectively (Hagan, 1998; Schrover et al., 2007). To sum up, as a result of both unequal access to social capital and the unequal outcomes obtained from it, searching for work through social networks may perpetuate gendered and ethnic labour market inequalities.

Context, data and methods

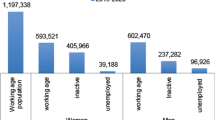

The data for this study form part of a broader project aimed to assess social cohesion in Catalonia, Spain, through the study of relationships both within and between social groups. The fieldwork was conducted in 2009 and 2010, just after a decade of a significant increase of the foreign-born immigrant population, which in Catalonia rose from 4% in 2000 to 17.5% in 2010 (data from the Municipal Population Register, Statistical Institute of Catalonia). That moment was also particularly marked by the Great Recession, which implied a massive loss of employment and substantial occupational immobility (Arranz et al., 2017). In 2010 the unemployment rate by that time was around 14.8%, but 30% for the immigrant population (data from the Labour Force Survey). The crisis affected the immigrant population particularly hard (Rinken et al., 2018), as they were already in a particularly vulnerable position when it started. Its impact was even worse for those who arrived latest in the Spanish labour market (Rodriguez-Planas and Nollenberger, 2016).

The data were collected by means of a survey of personal networks, administered to a sample of Ecuadorian and Moroccan immigrants (N = 153). In personal networks, the unit of reference is a specific informant (ego) and her relational setting, that is, the individuals with whom she is directly connected (the alters). The survey collected personal networks consisting of 30 contacts, therefore including both strong (close) and weak (distant) ties. To obtain this information, respondents were asked to name 30 people whom they knew by name and with whom they had had contact in the previous 2 years.Footnote 3 Interviews lasted an average of 2 h, as a lot of information about all 30 contacts retrieved by the interviewee was also collected.

The survey followed a non-probability quota sampling method. The sample was stratified in respect of the basic structural characteristics of the Catalan population by city of residence (three cities of different sizes, representing the variations in urbanization in Catalonia), age, gender and origin (country of birth). Multiple methods were used in recruiting participants.Footnote 4

A total of 446 interviews were conducted, 153 of which were with immigrants (77 Moroccans and 76 Ecuadorians) living in Catalonia.Footnote 5 These two ethnic groups were selected because they illustrate well the recent wave of immigration from the Global South that the country has received since the early 2000s. They are the two largest immigrant groups in Spain from outside the EU, and although they both came to Spain for economic reasons, they represent a variety of linguistic, religious and geographical backgrounds.

As shown in Table 1, the sample does not substantially differ from the reference population by sex or age, although the population with the highest educational level is slightly over-represented, especially among the Moroccan population.

After a brief description of immigrants’ networks, logistic regression analysis is used to test the effects of social capital, human capital and sector on the occupational status attained by Moroccans and Ecuadorians in Spain. Further analyses delve into gender differences by considering the interaction effect of each of the three explanatory factors with gender.

Acquired occupational status refers to the qualifications of the immigrant’s current or last job. It distinguishes business owners, professionals, qualified workers and workers with management responsibilities from workers without qualifications or only very low ones. The vast majority (98.7%) of those interviewed were wage-earners.

Regarding social capital, three variables were constructed, looking at the size of the sub-set of contacts with whom interviewees had exchanged labour-related supportFootnote 6 according to their ethnic origin and the location of the contact: autochthonous (born in Spain), co-ethnics living in their country of origin (transnational ties), or co-ethnics living in the host country (fellow immigrants in Spain). These variables were dichotomized in the regression analysis based on the median value.

Regarding human capital, the level of education is taken into account (low: basic and compulsory education; medium: secondary post-compulsory and professional education; and high: university degree). Finally, regarding the sector, the analysis takes into account whether the job is located within the ethnic niche: construction, agriculture, hotels and catering, retail and domestic work. In the full model, variables, such as country of birth, length of residence in Spain (in years) and gender are included as controls. Unfortunately, data on language competence or legal status are not available. See Table 2 for summary statistics.

Because of the small sample size, in order to avoid false negatives (LeBel et al., 2008), the significance levels are set at 0.05 (**) and 0.1 (*).

Results

Social networks and job-seeking among Ecuadorian and Moroccan immigrants in Spain

The exchange of employment-related information and assistance through social networks is very important among immigrants. In fact, possibly due to a lack of knowledge of the formal mechanisms of recruitment and because of the undocumented status of some of them, migrants exchange this kind of help with a higher proportion of their contacts (44.4%) than local native-born Spaniards do (34.1%) (p < 0.01).

However, not all contacts in immigrants’ networks provide or exchange this type of social support. In fact, autochthonous ties seem to be the most valuable in these regards, as 54.1% of such ties provide or receive employment-related information or assistance. Conversely, transnational ties with people in the home country appear to be less supportive when it comes to looking for jobs or solving employment-related issues, as only 34.6% of such contacts exchange this type of social support with the interviewees. Finally, employment-related social support is also exchanged with an important proportion (46.4%) of the co-ethnics living in Spain, showing that immigrants from the same place of origin settled in the host country are more able to provide this type of support than those living in the country of origin, although to a lesser extent than autochthonous contacts (Table 3).

The outcome of exchanging employment-related support through social networks

This section explores the role of social capital in the performance of immigrant labour markets. Following the first model, with social capital variables, three sets of models were generated, which gradually add human capital, sector and individual characteristics to the previous models.

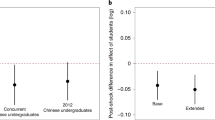

The results presented in Table 4 show that social capital is a relevant factor. To be more specific, exchanging labour-related support with autochthonous contacts is associated with being employed in a job with a higher occupational status. These results, moreover, are also found even when controlling for human capital, sector and other individual characteristics, indicating that this is a stable pattern not affected by other possible explanatory factors for immigrants’ labour market performance.

Regarding human capital, the second model shows that level of education is another good predictor of the occupational status attained. However, this effect ceases to be significant once the sector in which the immigrant works (as presented in model 3) has been controlled for. This suggests that, while those with higher academic qualifications might be in a better position to find a qualified job, if they end up in the immigrant occupational niche, those higher opportunities fade away. Other research also suggests that education may have a lower pay-off for immigrants than for natives in terms of occupational mobility because immigrants with higher levels of education also remain concentrated in sectors with poor job characteristics (Rodríguez-Planas and Nollenberger, 2016), and because their qualifications might not be fully recognized (Miguélez et al., 2013).

Finally, the full model shown in Table 4 indicates that, while ethnic group and length of residence in Spain are not statistically significant, gender is a powerful predictor of immigrants’ occupational status even when the effects of all the other variables are controlled for. In fact, these results confirm the existence of profound differences between the male and female labour forces in their patterns of insertion into the Spanish labour market, which provide fewer opportunities for immigrant women.

In order to determine whether social capital, human capital and ethnic concentration in occupational niches had a different return for immigrant men and women respectively in terms of occupational status, regression analyses setting the interaction effects were performed. These analyses, shown in Table 5, indicate that exchanging employment-related social support with autochthonous contacts remains a significant factor in attaining a higher occupational status, while its interaction with gender is not. This implies that, in line with the results that Kanas et al. (2011) present for Germany, social capital does not give a significant differential return depending on the worker’s gender. It might be noted, however, that segmented analyses show a much stronger effect of having autochthonous contacts in the network among men than among women: while men with this type of social capital work to a much greater extent in qualified occupations than those without it (68.6% vs. 34.1%), for women this asset does not have such a strong impact (only 34.5% work in a qualified occupation, just a few more than the 25.0% who do not have this type of social capital).

Working in the immigrant niche, conversely, has a clear differential effect for migrant men and women: the coefficient of working within the immigrant niche is almost zero (and, of course, non-significant), while the interaction between sector and gender appears to be a powerful predictor of the immigrants’ occupational status. This result points to the intersection of ethnic and gender-based axes in the segmentation of the labour market that configures labour-market inequalities: while immigrant men might have greater opportunities for vertical mobility even within the immigrant niche, for immigrant women the immigrant niche becomes a stronger trap, keeping women in undervalued positions within the secondary segment, which seem to have a strong ‘sticky floor’ (Torns, 1999; Parella, 2003).

According to further research, this trend might have been reinforced during the Great Recession, the most remarkable impact of which was the destruction of employment. In the initial stage (2008–2011) this destruction mainly took place in the construction sector, which affected in particular immigrant men. Later on (2011–2014), the exacerbation of the financial crisis and the spending cuts in the public sector also affected immigrant women (Gil-Alonso and Vidal-Coso, 2015). Nevertheless, the Great Recession also produced a worsening effect on employment conditions, hindering immigrants’ occupational mobility (Arranz et al., 2017), particularly for those women who had been regrouped by their male partners, therefore having a shorter period of residence and a migratory project subsidiary to their partners’ career (Moreno-Colom and López-Roldán, 2018). The high unemployment experienced during the crisis also fostered a discriminatory discourse that challenged the legitimacy of immigrants having employment at all, and it also pushed immigrant women to keep or re-occupy the most devalued positions such as intern in domestic service (Parella, 2012).

Conclusion

The data described in this article on the role of social networks in the labour market integration of immigrants clearly refute the assumption of the existence of a meritocratic labour market in which only human capital is rewarded by the market in the form of better jobs. Beyond individual factors, structural factors play an important role in explaining how migrants perform in the labour market, both the well-studied macro-structural elements, such as the occupational structure of the labour market, and the meso-level structure made of social relationships. In this sense, this paper shows that, even when the individual’s human capital and industrial sector are taken into account, the composition of networks of personal relationships creates and constrains employment opportunities for the individuals embedded in them.

Immigrants mobilize their networks in order to obtain information and support for job-seeking to a greater extent than the local Spanish population do. However, personal networks encourage different outcomes for individual immigrants’ depending on the composition of the network. In particular, for Moroccan and Ecuadorian immigrants in Catalonia (Spain) the type of social capital that has been featured as the most valuable for their occupational positioning is that composed of contacts with the native-born Spanish population. In contrast, ties with people living in the country of origin (i.e. transnational networks) are mobilized less in seeking employment-related support, and they are not related at all to the occupation of higher positions in the occupational structure, which questions the theory of the added value of transnational ties. Such ties might be a mechanism of business and professional success among high-status migrants (Gold, 2001) or post-industrial/high-skilled entrepreneurs (Kloosterman and Rath, 2010), but among recent Ecuadorean and Moroccan economic immigrants working mainly in the secondary segment of the labour market, local contacts should be regarded as more useful resources for obtaining labour market rewards than transnational ties.

Finally, the article also suggests that social capital should be understood in light of the wider context and dynamics of labour market segmentation that also play an important role in immigrants’ labour market performance. The article has shown that the specific structure of every labour market needs to be taken into account in order to study the relationship between social capital and its returns. In the Spanish case, the labour market is stratified according to ethnic differences and is crossed by gendered inequalities as well. Therefore, in the context of a sexually segregated labour market, immigrant working women face both ethnic occupational segregation and horizontal and vertical gendered discrimination that places them in undervalued jobs that are closely related to social care. Ethnic and sexual divisions of labour confine immigrant women in a closed and rigid position in the secondary labour market, without possibilities for promotion and with a ‘sticky floor’ (Torns, 1999; Parella, 2003) that hinders their professional development (Grimshaw et al., 2017). In this context, the structure of the labour market seems to make social capital a slightly weaker resource for women immigrants. These results point to the need to consider immigrants’ social capital in light of the intersectionality framework in order to understand how the nature and effects of (ethnic) relationships are crossed by multiple social divisions (Anthias, 2007). Just as human capital might have less salience for immigrant workers as a result of misrecognition and undervaluation of their skills, different forms of social capital also have different effects on social stratification depending on the social location of both the reaching out and reached out actors.

The research presented in this article faces a limitation: it is not possible to assume a one-way causality in the relationship between social capital and labour market performance. On the contrary, there might also be reverse causation (Mouw, 2006), or a complex web of causes and consequences, as the labour sphere is itself a space where networks are developed, allowing immigrants to meet people who might help them in the job search and in their further development. Nevertheless, the article has pointed to associations that provide interesting insights into the dynamics of inequality underlying the position of immigrants in the Spanish labour market. Another limitation has to do with the small N used in the analyses, which does not allow statistical assessment or inference of the results, but only identification of the trends and internal variations in the data. Given the length of questionnaires on personal networks, in personal network surveys small Ns are common, as a result of the trade-off between the number of interviewees and the extension and depth of the information on the network that surrounds every interviewee. In the case of this research, this has provided rich information on the different types of social capital that migrants might have when mobilizing their entire network, including both strong and weak ties.

To conclude, further research may explore this topic in greater depth by combining quantitative data with qualitative data or by working with a longitudinal design. That may allow us to study how networks are created in different life spaces in interaction, and how they influence the ability to obtain resources that may change the opportunity to create new networks. New data are thus needed in order to clarify the causality of the results presented. Further research may also incorporate into the models the distinction between the origin of the human capital of migrants—that is, whether it is acquired in the country of origin or in the host country (Kanas et al., 2011)—and their language skills (Bloch, 2013). Legal status should also be considered in more detail, as rights to residence, work and welfare depending upon immigrants’ status have been shown to contribute to the creation of racialized and gendered socially constructed definitions of work that operate to increase susceptibility to severe exploitation (Lewis et al., 2015).

Nevertheless, the results presented here may help us understand how ethnic and gender inequalities are reinforced in immigrants’ access to and development in the Spanish labour market. It contributes to strengthening an explanation for inequality (Johnson, 2000) that is based on social, cultural, political and economic barriers and structures, rather than on market rewards for responsible individuals’ choices.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The concept of ‘ethnic or immigrant occupational niches’ refers to a set of economic activities (sectors or occupations) in which immigrants are heavily concentrated (i.e. the percentage of immigrants or ‘group members’ being at least one-and-a-half times greater than the group’s percentage of all employment) (see Waldinger, 2001).

Unlike the traditional concept of community that is based on group and territorial belonging, personal communities shift this spatial definition to relationally defined communities (Chua et al., 2011).

Fixing the number of contacts is considered the best strategy in order to avoid bias in recall due to different interpretations of the question, memory problems, fatigue, desirability or a lack of cooperation (McCarty, 2002). Respondents were given the following prompt: ‘Please name a list of thirty people whom you know by name (and who know you by name) with whom you have had contact at least once in the last two years by any means of communication, and whom you could contact again if necessary. Do not include individuals under eighteen years old, but any other person can be included. Try to include people who are close and important to you. Then you can include people who are not close but whom you see often. You can extend your memory to other people. It may help you to think about different groups of people in different places, e.g. family, friends, workmates, neighbours, etc.’. Moreover, interviewees were encouraged to use nicknames or abbreviations to refer to their contacts to avoid privacy concerns.

A broad range of strategies were pursued to recruit research participants in different milieus. Respondents were located with the aid of diverse institutions and organizations, as well as with posters on the streets, “call shops” and cyber-cafés, markets, schools, public equipment, and online sites. Participants signed an informed consent form with an agreement to respect anonymity and confidentiality. A small financial compensation was offered. Snowballing sampling techniques were kept to the minimum in order to prevent overlaps in the observed networks.

The other 293 were native-born Spaniards. The whole data set is used to provide some comparison between migrants and locals, but the main focus is on the analysis of migrant cases. Unfortunately, there are valid data on occupational status in only 137 cases.

To be more specific, the questionnaire asked the following: Has this person provided you (or vice versa), whether in the present or in the past, with useful information or other means of support or assistance in finding employment or solving work-related problems?

References

Aguilera MB, Massey DS (2003) Social capital and the wages of Mexican Migrants: new hypotheses and tests. Soc Forces 82(3):671–701

Anthias F (2007) Ethnic ties: social capital and the question of mobilisability. Sociol Rev 55(4):788–805

Anthias F (2012) Hierarchies of social location, class and intersectionality: towards a translocational frame. Int Sociol 28(1):121–138

Arranz JM, Carrasco C, Massó M (2017) La movilidad laboral de las mujeres inmigrantes en España (2007–2013). Rev Espanola de Sociologia 26(3):329–344

Becker G (1983) El capital humano. Alianza Editorial, Madrid

Behtoui A, Neergaard A (2010) Social capital and wage disadvantages among immigrant workers. Work Employ Soc 24(4):761–778

Bloch A (2013) The labour market experiences and strategies of young undocumented migrants. Work Employ Soc 27:272–287

Bolíbar M (2016) Macro, meso, micro: broadening the ‘social’ of social network analysis with a mixed methods approach. Qual Quant 50(5):2217–2236

Bolibar M, Martí J, Verd JM (2015) Just a question of time? The composition and evolution of immigrants’ personal networks in Catalonia. Int Sociol 30(6):579–598

Bottero W, Crossley N (2011) Worlds, fields and networks: becker, bourdieu and the structures of social relations. Cult Sociol 5(1):99–119

Bourdieu P (1986) The forms of capital. In: Richardson J(ed.) Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education. Greenwood Press, New York, NY, pp. 241–258

Bowles S, Gintis H (1975) The problem with human capital theory—a Marxian critique. Am Econ Rev 65(2):74–82

Cachón L (2003) Discriminación por motivos de origen en el mercado laboral. In: Española CR (ed) Empleo e immigración: Estratégias de comunicación para la promoción de la igualdad de trato. Cruz Roja Española-Oficina central, Madrid

Cachón L (2009) La España inmigrante: marco institucional, mercado de trabajo y políticas de integración. Anthropos, Barcelona

Carrington P, Scott J (2011) Introduction. In: Scott J, Carrington P (eds) The Sage handbook of social network analysis. Sage Publications Ltd, London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi, pp. 1–8

Cheong PH, Edwards R, Goulbourne H, Solomos J (2007) Immigration, social cohesion and social capital: a critical review. Crit Soc Policy 27(24):24–49

Chiswick BR (1978) The effects of Americanization on the earnings of foreign born men. J Political Econ 86:897–921

Chiswick BR, Lee YL, Miller PW (2003) Patterns of immigrant occupational attainment in a longitudinal survey. Int Migr 41(4):47–69

Chua V, Madej J, Wellman B (2011) Personal communities: the world according to me. In: Carrington PJ, Scott J (eds) The Sage handbook of social network analysis. Sage, Londres

Coleman JS (1988) Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol 95:S95–S120

De Miguel V, Tranmer M (2010) Personal support networks of immigrants to Spain: a multilevel analysis. Soc Netw 32:253–262

Degenne A, Forsé M (1999) Introducing social networks. Sage Publications, London

Gil-Alonso F, Vidal-Coso E (2015) Inmigrantes Extranjeros En El Mercado De Trabajo Español: ¿Más Resilientes O Más Vulnerables Al Impacto De La Crisis? Migraciones 37:97–123

Gold SJ (2001) Gender, class, and network: social structure and migration patterns among transnational Israelis. Glob Netw 1(1):57–78

Granovetter M (1973) The strength of weak ties. Am J Sociol 78(6):1360–1380

Granovetter MS (1974) Getting a job: a study of contacts and careers. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Grimshaw D, Fagan C, Hebson G, Tavora I (2017) A new labour market segmentation approach for analysing inequalities: introduction and overview. In: Grimshaw D, Fagan C, Hebson G, Tavora I (eds) Making work more equal. Manchester University Press, Manchester, pp. 1–32

Hagan J (1998) Social networks, gender and immigrant incorporation: resources and constraints. Am Sociol Rev 63(1):55–67

International Labour Organization (2012) From precarious to decent work: outcome document to the Workers’ Symposium on policies and regulations to combat precarious employment. International Labour Organization, Geneva

Johnson CF (2000) Racial disparities and neoclassical economics: the poverty of human capital explanations. Soc Sci J 37(3):459–464

Kanas A, van Tubergen F, Van der Lippe T (2011) The role of social contacts in the employment status of immigrants: a panel study of immigrants in Germany. Int Sociol 26(1):95–122

Kloosterman R, Rath J (2010) Shifting landscapes of immigrant entrepreneurship. In: OECD (ed), Open for business: migrant entrepreneurship in OECD countries. OECD Publishing, pp. 101–123

Lancee B (2012) The economic returns of bonding and bridging social capital for immigrant men in Germany. Ethn Racial Stud 35(4):664–683

Lancee B (2010) The economic returns of immigrants’ bonding and bridging social capital: the case of the Netherlands. Int Migr Rev 44(1):202–226

LeBel TP, Burnett R, Maruna S, Bushway S (2008) The ‘Chicken and Egg’ of subjective and social factors in desistance from crime. Eur J Criminol 5(2):131–159

Levitt P, Glick-Schiller N (2004) Conceptualizing simultaneity: a transnational social field perspective on society. Int Migr Rev 38(3):1002–1039

Lewis H, Dwyer P, Hodkinson S, Waite L (2015) Hyper-precarious lives: migrants, work and forced labour in the Global North. Prog Hum Geogr 39(5):580–600

Lin N (1999) Social networks and status attainment. Annu Rev Sociol 25(1):467–487

Livingston G (2006) Gender, job searching, and employment outcomes among Mexican immigrants. Popul Res Policy Rev 25(1):43–66

Lozares C, Verd JM, López-Roldán P, Martí J, Molina JL (2011) Cohesión, Vinculación e Integración sociales como formas de Capital social. REDES Rev Hisp Anál Redes Soc 20(1)

Lubbers MJ, Molina JL, Lerner J, Brandes U, Ávila J, McCarty C (2010) Longitudinal analysis of personal networks: the case of Argentinean migrants in Spain. Soc Netw 32(1):91–104

Martinez Veiga U (1997) La integración social de los inmigrantes extranjeros en España. Editorial Trotta, Madrid

Massey DS, Arango J, Hugo G, Kouaouci A, Pellegrino A, Taylor JE (1993) Theories of International Migration: a review and appraisal. Popul Dev Rev 19(3):431–466

Maya-Jariego I (2001) Tipos de redes personales de los inmigrantes y adaptación psicológica. REDES Rev Hisp Anál Redes Soc 1(4)

McCarty C (2002) Structure in personal networks. J Soc Struct 3. http://www.cmu.edu/joss/

Miguélez F (coord.), Antonio M, De Alós-Moner R, Esteban F, López-Roldán P, Molina O, Moreno S (2011) Trayectorias laborales de los inmigrantes en España. Obra Social “La Caixa.”, Barcelona

Miguélez F, Molina Ó, López-Roldán P, Ibáñez Z, Godino A, Recio C (2013) Nuevas estrategias para la inmigración: recualificación para un nuevo mercado de trabajo. QUIT Working Pap Ser 18:1–227. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.3362.8320

Molina JL, Lerner J, Gómez Mestres S (2008) Patrones de cambio de las redes personales de inmigrantes en Cataluña. REDES Rev Hisp Para Anál Redes Soc 15(4):48–61

Moreno-Colom S, López-Roldán P (2018) El impacto de la crisis en las trayectorias laborales de las mujeres inmigrantes en España. Cuaderno de Relaciones Laborales, vol. 36(1), pp. 65–87

Mouw T (2006) Estimating the causal effect of social capital: a review of recent research. Annu Rev Sociol 32:79–102

Pajares M (2005) La integración ciudadana. Icaria, Barcelona

Pajares M (2010) Inmigración y mercado de trabajo. Informe 2010. In: Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigración (ed) Documentos del Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigración, vol. 25. Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración, Madrid

Parella S (2003) Mujer, inmigrante y trabajadora: la triple discriminación. Anthropos, Barcelona

Parella S (2012) El retraso de la recuperación económica y sus efectos sobre la fuerza de trabajo inmigrante Anuario IET de Trab y Relaciones Laborales 2012: Las Reformas y El Empl, Anthropos, vol. 1, pp. 195–205

Piore MJ (1975) Notes for a theory of labour market stratification. In: Edwards R, Reich M, Gordon D (eds) Labor market segmentation. Heath, Lexington, pp. 125–150

Portes A (1998) Social capital: its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annu Rev Sociol 24:1–24

Portes A, Rumbaut RG (2010) América inmigrante. Anthropos, Barcelona

Rinken S, Godenau D, Martínez de Lizarrondo A (2018) La integración de los inmigrantes en España ¿Pautas diferenciadas en distintas etapas de la crisis? Anuario CIDOB de La Inmigración, pp. 238–259

Rodríguez-Planas N, Nollenberger N (2016) Labor market integration of new immigrants in Spain. IZA J Labor Policy 5(4):1–15

Sanders J, Nee V, Sernau S (2002) Asian immigrants’ reliance on social ties in a multiethnic labor market. Soc Forces 81(1):281–314

Schrover M, van der Leun J, Quispel C (2007) Niches, labour market segregation, ethnicity and gender. J Ethn Migr Stud 33(4):529–540

Torns T (1999) Las asalariadas: un mercado con género. In: Prieto C, Miguélez F (eds.) Las relaciones de empleo en España. Siglo XXI de España Ed, Madrid, pp. 151–166

Trimble LB, Kmec JA (2011) The role of social networks in getting a job. Sociol Compass 5(2):165–178

Veira A, Stanek M, Cachón L (2011) Los determinantes de la concentración étnica en el mercado laboral español. Rev Int Sociol 69(1):219–242

Vertovec S (2009) Transnationalism. Routledge, London

Waldinger R (1994) The making of an immigrant niche. Int Migr Rev 28(1):3–30

Waldinger R (2001) The immigrant niche in global city-regions: concept, patterns, controversy. In: Scott Allen J (ed) Global city-regions: trends, theory, policy. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp. 299–322

Wellman B (1979) The community question. Am J Sociol 84:1201–1231

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation under the research grants “Estudio comparado de casos sobre la influencia mutua entre el capital e integración sociales” (CSO2008-01470), and “Precariedad laboral y estrés: factores sociales con impacto biomédico” (CSO2017-89719-R, AEI/FEDER, UE). Moreover, MB holds a Juan de la Cierva Incorporación fellowship granted by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolíbar, M. Social capital, human capital and ethnic occupational niches: an analysis of ethnic and gender inequalities in the Spanish labour market. Palgrave Commun 6, 22 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0397-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0397-4