Abstract

Although many studies have investigated relationships between emotional labour and emotional intelligence among hospital staff, few have paid attention to social intelligence in this field. This study explored the relationships between emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism among physicians in governmental hospitals in Jordan. The goal was to improve the understanding of the causes of patients abusing physicians in Jordan. Some patients have maintained that physicians are responsible for hostile behaviour against them, as these resulted from medical errors, physician negligence, and a failure to provide adequate care, exacerbated by physician narcissism, lack of empathy, verbal miscommunication, and lack of sympathy in critical cases. Findings confirmed that whenever physicians engage in strategies of emotional labour, they display higher social intelligence and lower levels of narcissism. Moreover, social intelligence does not mediate the relationship between emotional labour and narcissism. The results of the study suggest that interventions by the Jordan Medical Association to reduce physical and verbal assaults on physicians should encompass more than a mere legal focus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Physical and verbal assaults on physicians have increased in Jordan, especially in government hospitals, despite the heavy penalties imposed upon assailants of physicians and medical staff in hospitals. The Jordan Medical Association (JMA) recorded 111 physical assaults between 2016 and 2019, and the Ministry of Health recorded more than 600 cases of physical assault on physicians in the period 2010–2019. The phenomenon of physicians being abused at their workplace by patients is widely spread in many countries across the world (Reddy et al., 2019). The study of Ghosh (2018) indicated that reports of violence against physicians are making global headlines. Ghosh also confirmed that such violence is on the rise in India, and that India’s medical journals include discussions on the matter. Ghosh further referenced a study by the Indian Medical Association (IMA) (2017), which reported that 75% of physicians in India have faced violence, especially verbal abuse. Violence against physicians has also been frequently reported in the United States (Kuhn, 1999), the United Kingdom (Ness et al., 2000), China (Cai et al., 2019), and Israel (Carmi-Iluz et al., 2005).

In this context, the JMA proposed its favoured legal solution in 2016—to deploy a security detachment to emergency departments where these attacks abound. In 2019, the JMA suggested that the Ministry of Health (instead of physicians) take over pleading-and-follow-up orders. In the same year, the Parliamentary Health and Environment Committee recommended reviewing Article 187 of the Jordanian Penal Code No. 16 to increase the punishments as a deterrent against attacks on physicians (up to 3 years of jail time). However, citizens maintained that the physicians were responsible for hostile behaviour against them, as these resulted from medical errors, physician negligence, and a failure to provide adequate care. The JMA also indicated in 2019 that healthcare problems are caused by a lack of medical staff and disproportionate numbers of patients, obligating some medical staff to work more hours than the law permits. While patients have acknowledged the existence of these problems, they have argued that the following exaggerated their issues: physician narcissism, lack of empathy, verbal miscommunication, and lack of sympathy in critical cases.

There are a few existing studies that explore assaults on physicians in Jordan. Alquisi (2016) aimed at identifying the causes and types of violence against the medical staff in hospitals in Jordan, which included the following: impulsiveness, an absence of dialogue, strict opinions, tribalism, and a predominance of clan and cultural values. Alquisi (2016) also found that patients threatened physicians with jail time/murder and failed to show them respect. Al-hourani (2013) studied the role of the physicians’ expectations in relation to patient violence against them in Jordan. Three types of expectations were identified: humanity, accountability, and fidelity. The study found that there was a statistically significant relationship between the patients’ expectations from physicians and violence against physicians. Similarly, Rawash (2011) Violence against doctors in the hospitals of the public sector: symbolic interaction perspective, Unpublished Master Thesis, Yarmouk University, Jordan) concluded that the causes of violence against physicians in Jordanian government hospitals resulted from negative exchanges between patient and physician. The results highlighted that Jordanian physicians acknowledged that the reason for inadequate interactions with their patients, in addition to the violence they faced, was a result of complex hospital systems and a shortage of medicine/medical equipment.

To understand the causes of the gap between patients and physicians behind the increase in cases of abuse, it is necessary to be aware of the emotional labour of physicians and its relationship to the level of their social intelligence, especially in light of patients’ accusations of physician narcissism. Emotional labour—the process of managing emotions and emotional expression to fulfil the emotional requirements of a task (Hochschild, 1983)—is an important consideration in research on organisational outcomes in the service sector. There is increasing evidence to suggest a positive relationship between physician job satisfaction and patient satisfaction, as well as health outcomes (Nwankwo et al., 2013). Further, according to Larson and Yao (2005), empathy should characterise physicians’ interactions with their patients because the interpersonal relationship between physician and patient remains essential to quality healthcare. Therefore, physicians consider empathy a form of emotional labour that depends on two strategies: surface acting and deep acting. Physicians may rely on surface acting when sincere empathy for patients is impossible (Larson and Yao, 2005).

In this study, the researcher assumed that physicians are likely to be the most rational party in a treatment situation, especially those working in the emergency and surgical departments. The patient, as the result of the healthcare process, suffers from a combination of emotions—such as the loss of a loved one, the cost of treatment, post-traumatic responses and symptoms, the suffering of a chronic illness—and is largely passive. This reduces the patient’s ability to communicate and disorients their understanding of the therapeutic scene, potentially resulting in irrational behaviour. In this context, this study explores the relationships between emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism among physicians in governmental hospitals in Jordan and, accordingly, develops several hypotheses. This research incorporates a survey design and uses the Tromso Social Intelligence Scale (TSIS), the Deep Acting and Surface Acting Scale (DASAS), and the Grandiose Narcissism Scale (GNS) to quantify the survey results. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was used to test the proposed hypotheses. The study aims to explore the correlations between these constructs and to provide data related to emotional labour strategies for physicians. As stated previously, prior studies have confirmed the effectiveness of such strategies in improving the relationship between physicians and patients. This study, therefore, can improve the understanding of the causes of patients abusing physicians in Jordan. The researcher expect that this study will be useful for institutions and researchers interested in studying this phenomenon in the future.

Emotional labour (EL): conceptual framework and hypothesis development

In the study of emotions, symbolic interactionist studies are based in large part on the work of Mead (1934), Blumer (1969), and Goffman (1959, 1963, 1967). Symbolic interactionism is a sociological perspective that has been particularly influential in microsociology and social psychology. It focuses on the study of emotions in social interactions, and the formation of a social self through emphasis on the role of identities and self-conceptions in regulating behaviour. When an individual is able to reaffirm her or his self-conception or identity in a situation, positive emotions are generated and experienced. However, when problems arise in self-confirmation, individuals experience negative emotions that cause pain for themselves and encourage them to employ defensive strategies and invoke defence mechanisms that distort their experiences and emotions; in an attempt to avoid this pain, they will attempt to change their emotional experience and responses to others. In this context, symbolic integrationists interpret how individuals use their abilities to let their emotions align with the emotions that are expected from them (Turner and Stets, 2005). This perspective refuses the hypothesis that emotions are innate or universal responses to external stimuli that exist but rather holds that they are socially constructed. Most symbolic integrationists acknowledge the physiological aspects of emotions and feelings, especially when they study the idea of ‘role-taking emotions’, or feelings previously presuming to assume the role. Meanwhile, the individual will presume the other’s perspective and respond accordingly, which may require a social self; this includes responses such as feeling guilt, shame, and sympathy, and embracing when receiving bad news. Therefore, role-taking emotions reinforce self-control and social control, which may help in maintaining social fabric (Fields et al., 2006; Scheff, 2014; Shott, 1979).

The study of emotions has proven critical in interpreting the relationship between individual agency and social structure; this may lead to the sociological theorisation of the study of emotions to include job and organisations as the symbolic interactionism theory has become widespread in establishing the sociology of emotions through the concept of ‘emotional labour’. The concept of emotional labour was developed by Arlie Hochschild in her 1983 book, ‘The Managed Heart’ to facilitate the understanding of feelings at the workplace. According to Hochschild (1983), emotional labour refers to managing personal feelings and expressions based on the emotional requirements of a particular job. In this context, social processes are integral to emotions and responsible for managing feelings, and social structures and institutions impose restrictions on individuals’ efforts to form and direct their feelings. In addition, Hochschild refers to ‘feeling rules’, or socially shared norms that influence the emotions people expect to experience in particular social relations. In the workplace, employees strive to adhere to these rules through attempts to align privately felt emotions with normative expectations, or to bring the outward expression of emotions in line with inward experience. Thus, employees are expected to manage their on-the-job emotions according to the rules and instructions determined by their employer. This is especially true for service jobs where employees are generally expected to manage their feelings in their continued interactions with customers; in this way, the transformation of emotion management into emotional labour becomes a formal job requirement (Wharton, 2009).

Components of emotional labour

According to Hochschild (1983), an employee works at managing their emotions as a professional requirement through deep acting and surface acting. Biron and Veldhoven (2012) suggest that the need to organise one’s emerging emotions—i.e., thoughts and feelings—by blocking, changing, or controlling them is common to both deep and surface acting. Brotheridge and Lee (2003) confirmed the importance of distinguishing between surface and deep acting on account of the fundamentally different internal state of each and the different effects on employee well-being they may have. Despite the different underlying processes, they share the common aim of showing the positive feelings that should affect customers’ feelings and achieve the organisation’s goals, such as positive sales, client recommendations, and repeat business (Grandy et al., 2013; Pugh et al., 2013).

Deep acting

Deep acting is an exerted effort through which employees change their internal feelings to align with organisational expectations, producing more natural and genuine emotional displays (Biron and Veldhoven, 2012, p. 1263). Deep acting involves ‘pumping up’ by trying to bring the required emotions and one’s true feelings into alignment (Brotheridge and Lee, 2003, p. 366). In other words, employees attempt to experience the emotions they are expected to show to customers (Asumah et al., 2019) The expression of this feeling and its implication for meeting social expectations hold professional benefits for employees (Jeong et al., 2019).

Hochschild divided deep acting into passive and active acting. Passive deep acting occurs when employees spontaneously feel what they are required to feel, whereas active deep acting indicates that employees actively attempt to influence what they feel in order to embody the role they are asked to play (Yagil, 2008). Deep acting could be achieved through two ways: ‘exhorting feeling’ by stimulating or suppressing feelings, and ‘trained imagination’ by actively calling for thoughts and memories to stimulate the related emotions, such as thinking about death to feel sad. Therefore, employees use deep acting to change their feelings by deliberately visualising a substantial portion of reality in a different way (Asumah et al., 2019, p. 493; Yagil, 2008, p. 22).

Surface acting

Surface acting occurs when employees display the emotions required for work without changing what they are actually feeling (Hochschild, 1983). In other words, an employee who is engaging in surface acting suppresses their actual feelings while simulating an emotional performance according to organisational instructions (Biron and Veldhoven, 2012) in a ‘pushing down’ of one’s authentic expression of self in favour of an emotional mask (Brotheridge and Lee, 2003, p. 366). This ‘mask’ is achieved by changing one’s external appearance to display the required emotions by careful presentation of nonverbal cues, such as facial expression, gestures, or voice tone) Asumah et al., 2019). Surface acting is limited to modifying behavioural expressions of emotion, thus matching Goffman’s (1959) description of impression management in social interactions (von Scheve, 2012, p. 4). Furthermore, Brotheridge and Lee (2003) indicate that the end state of surface acting is misalignment and inauthenticity, both of which reduce one’s sense of well-being and potentially endanger employees’ health, for example, by causing emotional exhaustion (Pugh et al., 2013), However, the extent to which an employee identifies with their work role may determine the motive for why they engage in surface acting, i.e., ‘faking in good faith’ (Brotheridge and Lee, 2003, p. 366).

Emotional labour and medical practice

The study of emotional labour in healthcare is appropriate and necessary, due to the emotionally charged nature of the field. The expression of emotions is considered a non-professional practice that does not comply with the rationality of the medical profession (Kerasidou and Horn, 2016). As advanced technology and economic rationalisation become more prevalent in healthcare, it becomes difficult to remain authentically emotional and caring in institutions where new production standards do not allow for generous hospitality and link performances of emotionality to profitability. Further, the human gift of ‘paying respect with feeling’ has been transformed into a commodified form of emotional labour (Erickson and Grove, 2008, p. 2). Therefore, physicians suppress most forms of emotional expression and exhibit ‘affective neutrality’ by invoking the rhetoric of science to justify emotion management through displays of rationality by drawing from scientific jargon that they learned during their formal medical study rather than intimate or personalised language. Moreover, they tend to focus on technical details and avoid disturbing communication, thereby retaining a more powerful position in relation to their emotionally expressive patients, thus reinforcing their identity and authority as physicians (Fields et al., 2006, p. 161). In addition, it may be difficult to meet their professional commitments pertaining to clinical efficiency while simultaneously being sympathetic with patients; thus, by outwardly maintaining a professional image, a rational physician who is emotionally separated from their profession can overcome feelings of sympathy (Kerasidou and Horn, 2016). However, this inability of care providers to manage emotions may cause problems for them or their patients. For example, it may lead to situations in which caregivers display disrespect and a lack of care and empathy—one of the most prevalent reasons for complaints from patients and their families (Kinman and Leggetter, 2016). It may also lead to depression and exhaustion in physicians (Kerasidou and Horn, 2016).

The implementation of elements of emotional labour can result in increased success in providing healthcare while reducing the possibility of medical malpractice. It may also increase job satisfaction and result in more effectively provided treatment, which increases patient trust in their physicians as well. Such increased trust may positively affect patient recovery and satisfaction regarding their interactions with and respect for their physicians (Kerasidou and Horn, 2016; Lan and Yan, 2017; Larson and Yao, 2005).

Components of emotional labour and narcissism

Surface acting problems can lead to different types of psychological disorders (Grandey et al., 2004). However, employees who engage in deep acting show higher levels of empathy toward the clients (Genç, 2013). In this study, it is assumed that emotional labour lowers physician narcissism and prevents aggressive behaviour of physicians towards patients. Based on the above discussion and evidence, the following hypotheses have been formulated.

H1: There is a statistically significant relationship between surface acting and narcissism.

H2: There is a statistically significant relationship between deep acting and narcissism.

Components of emotional labour and social intelligence

Previous studies have provided evidence that there is a significant association between surface acting and social intelligence and between deep acting and social intelligence (Genc and Genc, 2018). Specifically, the existing findings are as follows: (1) managers’ social intelligence is significantly and negatively related to employees’ surface acting; (2) managers’ social intelligence is significantly and positively related to employees’ deep acting. Previous research has also established that employee emotions affect how employees interact with customers (Jung and Yoon, 2014; Kim, 2008; Lee et al., 2016). Accordingly, the following hypotheses have been formulated.

H3: There is a statistically significant relationship between surface acting and social intelligence.

H4: There is a statistically significant relationship between deep acting and social intelligence.

Social intelligence and physician narcissism

The roots of social intelligence theory date back to Thorndike’s (1920) conclusion that individuals have the ability to deal with men, women, boys, and girls, understand their motives and behaviours, and manage this knowledge. Moreover, Silvera et al. (2001) proposed that the dimensions of social intelligence are processing of social information, social skills, and social awareness.

Many studies discuss how crucial social skills and emotional intelligence are for hospital staff. A physician’s emotional intelligence plays a vital role in increasing patient satisfaction scores and communication skills, while ensuring continuity of care and a good physician–patient relationship. It can also help healthcare organisations deliver better, higher-quality service and more compassionate care (Lin and Chang, 2015; Psilopanagioti et al., 2012; Ravikumar et al., 2017). Social intelligence for physicians, by contrast, is an under-researched topic, particularly regarding the relationships, whether direct or indirect, between social intelligence and the components of emotional labour. In this study, the researcher assumed that social intelligence has a direct or indirect relationship with the components of emotional labour and that it plays a role in the healthcare.

Narcissism as a ‘normal’ dark personality trait is characterised by the expression of pride, egotism and vanity, and is potentially present within the healthcare profession. Moreover, it is worth noting that narcissistic personality disorder is highly comorbid with other disorders and associated with significant functional impairment and psychosocial disability (Caligor et al., 2015, p. 415). In this context, mainstream stereotypes abound about physicians being self-centred or arrogant because they feel that their abilities and social status are greater than that of others; in addition, they have also been described as avaricious and untrustworthy (Bucknall et al., 2015).

Leon et al. (2018) discuss the term difficult physician or problem physician and also examine personality disturbances among physicians; they indicate that narcissism and arrogance in physicians lead to a self-inflated self-image that causes difficulties in the workflow of a medical organisation. Further, they suggest that ‘disruptive physicians’ must focus on ‘empathy’ and not use it to ‘manipulate’ people but to help them. This will ensure better performances especially in medical specialties requiring interactions with patients. Moreover, fragile self-esteem has been shown to manifest in defensive, often aggressive behaviour. Alexander et al. (2010) measured physician narcissism as a proxy for high but fragile self-esteem and found that physicians with high narcissism levels were more likely to respond to ego threats by attempting to bolster their self-image. Based on the above evidence, the researcher proposes the following hypotheses in regard to the relationships between emotional labour, physician behaviour, and relationships with patients (see Fig. 1 for a conceptual framework comprising all hypotheses.)

H5: There is a statistically significant relationship between social intelligence and narcissism.

H6: Social intelligence significantly mediates the relationship between emotional labour and narcissism.

Methods

Participants and data collection

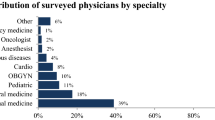

Data were collected through a survey distributed to 478 physicians in three government hospitals in the capital city of Amman. It is worth noting that the current study used a random sampling technique to collect data. Owing to restrictions imposed by the government as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was not possible for the researcher to collect data in person by interviewing the physicians. For this reason, the researcher had to use other means. Therefore, an online anonymous survey platform via Google Drive was used to collect data. Physicians who wished to respond were invited to respond to the study measures by making use of a link via social media whereby they could access the survey page and via email. Participants who consented to willingly participate in the survey would click yes on the first question in the survey, which was ‘Do you consent to participate in this study’? Once this option was selected by the physician, the physician would be directed to complete the self-administered questionnaire. The data were collected anonymously, without identification of the respondents. However, many physicians did not respond to the questionnaire because of their hectic routines caused by the pandemic. Thus, the total sample of this study was 140 physicians (100 males and 40 females).

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants.

Measures

-

1.

Surface and Deep-Acting Scales

The surface acting and deep-acting scales used in this study were developed by Diefendorff et al. (2005). The surface acting scale consists of seven items, and the deep-acting scale consists of four items. Participants rated each item using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = ‘Strongly Agree’; 1 = ‘Strongly Disagree’). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 for surface acting and 0.86 for deep acting, thereby indicating high reliability.

-

2.

Tromso Social Intelligence Scale

The TSIS scale developed by Silvera et al. (2001) consists of 21 items measuring social intelligence through self-reporting. It defines social intelligence based on three factors: social information processing or social perspective (e.g., ‘I can predict other people’s behaviour’), social skills (e.g., ‘I fit in easily in social situations’) and social awareness (e.g., ‘I often feel that it is difficult to understand other people’s choices’). Participants rated each item using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = ‘Strongly Agree’; 1 = ‘Strongly Disagree’). Cronbach’s alpha for social intelligence was 0.79 overall, with three subscales: social information processing (0.84), social skills (0.80) and social awareness (0.79). These scores indicated good reliability.

-

3.

Grandiose Narcissism Scale

The GNS developed by Ames et al. (2006) is the most widely used measure by non-clinical researchers and was used in this study to assess the extent to which physicians exhibit narcissistic tendencies. It contains 16 pairs of items, each consisting of two conflicting proposals between which physicians had to choose (e.g., ‘I like to be the centre of attention’ vs. ‘I prefer to blend in with the crowd’). Narcissistic responses were coded as ‘1’, and other responses were coded as ‘0’. A total score was calculated by summing the responses to all 16 items, with higher scores indicating the exhibition of greater narcissistic tendencies. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86, indicating high reliability.

Structural equation modelling

Along with standard statistical analysis (the Pearson correlation for the hypotheses, Alpha Coefficient, and hierarchical regression), this study also utilised structural equation modelling (SEM) for testing the proposed hypotheses. Genc and Genc’s (2018) research is an example of a related study that also used SEM for model testing. According to Hair et al. (2019, p. 607), ‘structural equation modelling (SEM) is a family of statistical models that seeks to explain the relationships among multiple variables‘. Except for SEM, other statistical techniques cannot be utilised to test entire theories while considering all possible information regarding research. The two SEM techniques that are the most popular among researchers are covariance-based SEM or CB-SEM and partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) (Hair et al., 2019). However, compared to the ‘hard modelling’ of CB-SEM with restrictive assumptions (e.g., normality assumption and larger sample sizes), PLS-SEM is termed as ‘soft modelling’ and performs well with non-normal or highly skewed data and smaller sample sizes (Hair et al., 2012; 2019). Moreover, non-metric or categorical data can also be easily analysed using PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). As one of the study’s constructs (narcissism) contains a dummy code or two categories (0 and 1), PLS-SEM was considered most suitable.

Results

Analysis of the data

The researcher used IBM SPSS-22 version for the statistical analysis of the collected data. Two types of statistics were used for the analysis of data. Descriptive statistics including frequency distribution and percentage of the data were used for analysis of demographic data. Pearson’s correlation coefficient r, and the alpha coefficient were used to test the hypothesis Meanwhile, the inferential statistics included a hierarchical regression.

Pearson’s correlation

Pearson’s correlation coefficient ‘r’ is a statistical test to investigate the degree of strength and direction of a relationship that exists between two variables. In this study, it was used to test the hypothesis of the relationship between social intelligence, emotional labour and narcissism and found the association and its direction among the three. The value of r indicated the degree of relationships among the variables. Conversely, the p-value showed whether either of the two variables were statistically significant or not. On the basis of the p-values, the hypotheses were either accepted or rejected.

Hierarchical regression

Hierarchical regression is a process used to indicate whether one variable shows a statistically significant amount of variance in comparison to all the other variables. It is not used as a form of statistical analysis but rather for comparisons of models.

Preliminary analysis

According to Table 2, the components of the Social Intelligence Scale (M = 72.4, SD = 6.4) were computed by adding the scores of its 21 items; meanwhile, the three subscales or factors, social information processing (M = 23.91, SD = 3.2), social skills (M = 24.3, SD = 3.73), and social awareness (M = 24.15, SD = 3.35), were also computed by summing the respective related items. The components of emotional labour (surface-acting and deep-acting scales) (M = 36.84, SD = 4.14) were computed by adding the scores of its 11 items, and further dividing it into in surface acting (M = 23.83, SD = 3.32) and deep acting (M = 13.0, SD = 2), which were computed by adding the seven and four items related to them, respectively. The values for narcissism (M = 10, SD = 2.62) were computed by adding all scores that were coded ‘1’.

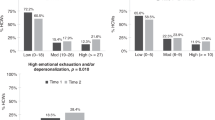

Pearson’s correlation analysis (H1, H2, H3, H4, H5)

As shown in Tables 3 and 4, there was no statistically significant correlation between surface acting and narcissism (r = −0.019, p = 0.823; Pearson’s r = −0.019). These values indicate a negative correlation; however, they are not significant. Thus, the hypothesis (H1) that surface acting is correlated with narcissism, was rejected. There was also no statistically significant correlation between deep acting and narcissism (r = 0.004, p = 0.961; Pearson’s r = 0.004). The results indicate that deep acting is positively correlated with narcissism, but the correlation is not statistically significant. Thus, the hypothesis (H2) that there is a statistically significant relationship between deep acting and narcissism was rejected. As for social intelligence, there was a statistically significant correlation between surface acting and social intelligence (r = 0.264, p < 0.05) and a statistically significant correlation between deep acting and social intelligence (r = 0.312, p < 0.05). Thus, social intelligence is strongly and positively correlated with surface acting as well as deep acting. Based on these results, hypotheses H3 and H4 were accepted. Finally, social intelligence and narcissism were not correlated (r = −0.163, p = 0.055; Pearson’s r = −0.163). Thus, H5 is unsupported by these findings.

Meditating analysis (H6)

Direct effect

Emotional labour has a statistically significant positive effect on the social intelligence scale (b = 0.5594, s.e. = 0.1225, p < 0.05) (Path a). This means that a higher level of emotional labour indicates higher social intelligence in a physician as compared to those who have lower scores in terms of emotional labour. On the other hand, social intelligence does not have a statistically significant positive effect on narcissism (b = 0.0331, s.e. = 0.0571, p = 0.56) (Path b). Further, emotional labour has a statistically significant negative effect on narcissism (b = −0.0744, s.e. = 0.0370, p < 0.5) (Path c), implying that physicians who exhibit a higher level of emotional labour will have a lower level of narcissism.

Indirect effect

A bootstrap method was used to analyse the indirect effect (IE = −0.0416), and this effect was not statistically significant: 95% CI (−0.0882, 0.0087). The indirect effect of emotional labour on narcissism is significantly less than zero. The effect of emotional labour on narcissism is not mediated by social intelligence; thus, hypothesis 6 (H6), which stated that social intelligence mediates the relationship between emotional labour and narcissism in physicians, is not supported by the findings.

Structural equation modelling (SEM) and model assessment

The measurement model, which illustrates how the estimated variables represent the constructs, and the structural model, which shows how the constructs are related, are both available in PLS-SEM (Hair et al., 2019). The researcher used SmartPLS (version 3) to test both models (Ringle et al., 2015). The measurement model specifies the theoretical relationship between the observed and latent constructs (Hair et al., 2019), and this is assessed via convergent and discriminant validities.

Construct validity

Construct validity is established when items related to a specific construct converge or commonly share a large proportion of variation (Hair et al., 2019). Meanwhile, composite reliability (CR) is used to assess the validity of the latent construct. Except for narcissism, all latent constructs had CR values greater than the recommended level (0.70) (Hair et al., 2019). The average variance extracted (AVE) is also used in association with CR, and an AVE lower than 0.50 is acceptable when the construct has a CR value >0.60 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981; Pervan et al., 2018). Table 5 displays the estimated construct validity of the latent constructs.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity assesses the extent to which each latent construct differs from the others (Hair et al., 2019). A construct has discriminate validity when the square root of AVE is greater than the correlations among the latent constructs. As illustrated in Table 5, the square roots for the AVE values were higher than the inter-construct correlations; therefore, the study constructs achieved discriminant validity.

Higher-order constructs

The researcher followed a repeated indicators approach to develop the ‘emotional labour’ and ‘social intelligence’ higher-order constructs. With this approach, the researcher could assign all lower-order constructs to higher-order constructs (Sarstedt et al., 2019). Therefore, all the items were assigned in the two lower-order constructs—deep acting and surface acting—as emotional labour. Similarly, all the items in the three lower-order constructs—social awareness, social information processing, and social skills—were assigned as social intelligence.

Structural model testing

Model one

The first model tested the hypotheses related to surface acting, social intelligence, and narcissism. Here, surface acting and narcissism were lower-order constructs, while social intelligence was a higher-order construct. The paths were drawn from surface acting to social intelligence and narcissism (e.g., surface acting → social intelligence and surface acting → narcissism) and from social intelligence to narcissism (e.g., social intelligence → narcissism) in order to estimate the path coefficients. The results showed that surface acting had no significant impact on narcissism (β = −0.129, p > 0.05) or social intelligence (β = 0.259, p > 0.05). Thus, there was insufficient evidence to support H1 or H3. The path coefficient (β = −0.129) indicated that when surface acting increased by 1 standard deviation (SD), narcissism decreased by 0.129 SD. Additionally, the path coefficient (β = 0.259) indicated that when surface acting increased by 1 SD, social intelligence increased by 0.259 SD. However, social intelligence had a significant and negative impact on narcissism (β = −0.374, p-value ~0.05); thus, the results from the first model provide support for hypothesis 5. The path coefficient (β = −0.374) indicated that when social intelligence was increased by 1 SD, narcissism decreased by 0.374 SD. (Fig. 2).

Model two

The second model tested the hypotheses in regard to the relationships between deep acting, social intelligence, and narcissism. Here, deep acting and narcissism were lower-order constructs, and social intelligence was a second-order construct. The paths were drawn from deep acting to social intelligence and narcissism (deep acting → social intelligence and deep acting → narcissism) and from social intelligence to narcissism (social intelligence → narcissism) in order to estimate the path coefficients. The results showed that deep acting did not significantly affect narcissism (β = 0.016, p > 0.05), failing to provide sufficient evidence to support H2. Deep acting significantly affected social intelligence (β = 0.402, p < 0.05), providing support for H4. The path coefficient (β = 0.016) indicated that when deep acting was increased by 1 SD, narcissism increased by 0.016 SD. Additionally, the path coefficient (β = 0.402) indicated that when deep acting was increased by 1 SD, social intelligence increased by 0.402 SD. Conversely, social intelligence had no significant impact on narcissism (β = −0.461, p > 0.05); thus, hypothesis 5 was not supported in the second model. The path coefficient (β = −0.461) indicated that when social intelligence was increased by 1 SD, narcissism decreased by 0.461 SD. (Fig. 3)

Model three

The third model tested the hypotheses in regard to the relationships between emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism. Here, narcissism was a lower-order construct, while emotional labour and social intelligence were higher-order constructs. The path was drawn from emotional labour to deep acting and surface acting (emotional labour→ deep acting and emotional labour→ surface acting) and from social intelligence to social awareness, social information processing, and social skills (social intelligence → social awareness, social intelligence → social information processing and social intelligence → social skills). Finally, paths were drawn from emotional labour to social intelligence and narcissism (emotional labour → social intelligence and emotional labour → narcissism) and social intelligence to narcissism (social intelligence → narcissism) in order to estimate the paths coefficients.

The results showed that emotional labour had an insignificant effect on narcissism (β = −0.069, p > 0.05). The path coefficient (β = −0.069) indicated that when emotional labour increased by 1 SD, narcissism decreased by 0.069 SD. In addition, emotional labour had a significant impact on social intelligence (β = 0.347, p < 0.05). The path coefficient (β = 0.347) indicated that when emotional labour increased by 1 SD, social intelligence increased by 0.347 SD. Moreover, social intelligence had an insignificant effect on narcissism (β = −0.397, p > 0.05); thus, hypothesis 5 (H5) was not supported in the third model. The path coefficient (β = −0.397) indicated that when social intelligence increased by 1 SD, narcissism decreased by 0.397 SD. Finally, the indirect effect in all three models showed that social intelligence does not significantly mediate the relationship between emotional labour and narcissism. Thus, hypothesis 6 (H6) was not supported. (Fig. 4) (Table 6)

Robustness test

The researcher used the coefficient of determination (R2), the effect size (f2), and Predictive relevance (Q2) to test the robustness and predictive capacity of the exogenous constructs (Hair et al., 2019).

Coefficient of determination (R 2)

The coefficient of determination (or R2) is used to assess the explanatory power of the structural model in partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). R2 ranges from 0–1, with higher values indicating that the model has better predictive power (Hair et al., 2019). The R2 value (0.18) in Table 7 indicates that emotional labour and social intelligence explain 18% of the variation in narcissism. Meanwhile, the R2 (0.12) value indicates that 12% of the variation in social intelligence is explained by emotional labour.

Effect size (f 2)

Effect size (f2) can be used to assess the impact on endogenous or outcome constructs as a result of removing an exogenous or independent construct (Hair et al., 2019). In other words, the f2 value denotes the changes that may happen in an endogenous construct (narcissism) if a predictor variable is omitted (social intelligence or emotional labour). Small, medium, and large effects can be explained by f2 values of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively. Table 8 illustrates that removing emotional labour had a small effect on narcissism and a medium-size effect on social intelligence. Conversely, removing social intelligence had a medium-size effect on narcissism.

Predictive relevance (Q 2)

Predictive relevance (Q2) is used to investigate the predictive accuracy of exogenous constructs (social intelligence or emotional labour) on an endogenous construct (narcissism) (Hair et al., 2019). A Q² value >0 indicates predictive accuracy. As illustrated in Table 7, all Q² values were >0, suggesting that the exogenous constructs have predictive relevance.

Discussion

To the researcher’s knowledge, this is the first study to address the issue of emotional labour of physicians in Jordan. After the legal and social arguments between patients and health officials, the exchange of accusations, and the listing of justifications of the causes of physician abuse, some decisions were made during the 2005 deans’ meeting of Arab medical colleges at Mu’tah University, Jordan. These decisions recommended teaching ‘community health’ and ‘medical ethics’ to medical students in order to develop their social communication skills, thereby potentially contributing both to improved communication between physicians, patients, and their companions and to reducing physician abuse. However, these changes were not implemented.

This study makes a novel contribution to the literature by seeking to understand the emotional labour of physicians. This is the first time such an approach has been used in Jordan to examine both the behaviour of physicians and the reasons why they are assaulted. The present study in particular casts light upon accusations of narcissism levelled against physicians. Additionally, it could potentially contribute to enrichment of socio-psychological solutions—that are proposed by the Medical Association—to challenge the phenomenon of abuse of physicians. Further, this study will also contribute to the enrichment of the field of research with regard to emotional labour by examining its relationship with social intelligence.

This study aimed to investigate the relationship among emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism in physicians. The results of the correlation analysis showed that emotional labour has a direct positive effect on social intelligence and narcissism—i.e., whenever physicians learn to use strategies of emotional labour, they exhibit higher social intelligence and lower levels of narcissism. Social intelligence is not negatively correlated with surface acting; in fact, deep acting has a significant effect on social intelligence. Meanwhile, surface acting is negatively correlated to narcissism, and deep acting has an insignificant effect on narcissism. However, social intelligence has a substantial positive effect on narcissism, and social intelligence does not mediate the relationship between emotional labour and narcissism.

Little attention has been paid to studying the relationship between social intelligence and emotional labour among physicians. In this context, Genc and Genc’s (2018) study—whose results are consistent to some extent with the present study’s findings—observed that social intelligence positively and significantly affects deep acting and negatively affects surface acting. Additionally, they found that surface acting did not have a mediating effect on social intelligence and that emotional labour does not have an intermediary role effect on managers’ social intelligence and emotional climate.

The results of the present study also confirmed that emotional labour has a direct positive effect on physicians. Physicians who practice emotional labour exhibit a higher level of social intelligence and a lower level of narcissism when interacting with patients. The researcher suggests that this dynamic may reduce potentially abusive verbal or physical confrontation with patients. There is increasing evidence to suggest that emotional labour has a positive effect on the healthcare process by enhancing patients’ confidence in physicians, increasing their satisfaction with their interactions with physicians and their experience of the treatment process, and making them demonstrate more cooperation (Kerasidou and Horn, 2016; Lan and Yan, 2017; Larson and Yao, 2005).

Meanwhile, Genc and Genc (2018) confirmed that emotional labour has an effect on individual behaviour, and Larson and Yao (2005) suggested that physicians may rely on surface acting when sincere empathy for patients is impossible. Moreover, Lin and Chang (2015) confirmed that surface acting for physicians has a direct impact on job performance. Surface acting during emotional labour is associated with higher physician job satisfaction and should be considered a desirable strategy for community healthcare workers in promoting effective and efficient work role performance (Pandey and Singh, 2016). Conversely, when physicians practice deep acting through generating empathy-consistent emotional and cognitive reactions, they become more effective healers and enjoy more professional satisfaction (Larson and Yao, 2005). These results support the present study’s finding that deep acting has a significant effect on social intelligence but an insignificant effect on narcissism; meanwhile, surface acting has no significant impact on narcissism or on social intelligence. In addition, this positive effect of deep acting upon physicians is confirmed by the results of the present study that show that deep acting has a positive and significant effect on social intelligence. However, there is a negative correlation between surface acting and narcissism, but it is not significant.

Despite these positive findings, there is increasing evidence that surface acting has negative effects and possibly several detrimental organisational outcomes. First, physicians cannot always have a positive attitude, and this may increase emotional exhaustion while reducing job performance and job satisfaction. In other words, when physicians display required emotions without accounting for how they actually feel, they do not feel emotion in their interpersonal relationships with colleagues and patients and thereby experience less job satisfaction (Kong and Jeon, 2018; Psilopanagioti et al., 2012). Likewise, deep acting is associated with lower job satisfaction (Pandey and Singh, 2016). The different results of studies in regard to the positive and negative effects of emotional labour upon physicians are dependent upon several factors, such as whether the job sector is governmental or private, what labour regulations exist, what the patient’s cultural background is, what the levels of affective commitment are, and what medical department the physician is staffed in.

However, the present study supported the hypothesis of the positive effect of emotional labour and the importance of physicians engaging in deep acting during treatment of patients. According to Hirsch (2007), physicians must not only identify but also understand the basis of the patient’s feelings. A physician may have a dissimilar cultural background from a patient, which may prevent the physician from adequately understanding the nature and circumstances of the patient’s emotional state, thus complicating the generation of an empathic response. Besides the cultural difference, there is the physician’s own commitment to the stereotype that forces them to be competent, rational, and emotionally disengaged while treating patients. Thus, Kerasidou and Horn (2016) confirmed that empathy should not only be expected from physicians but should be developed through several methods such as questionnaires that aid self-reflection and discussion groups with peers and supervisors on emotional experiences. For these methods to succeed, it is necessary to change the negative stereotype that inhibits physicians from engaging emotionally with their patients. Concomitantly, it is also important to improve the working conditions of physicians. Moreover, physicians should be socially adept and trained to strike a balance between emotional engagement and emotional detachment in order to avoid becoming excessively invested emotionally and to protect themselves from suffering emotionally and stressful situations (Dutton et al., 2014).

This study revealed the importance of physicians using their social intelligence to manage the emotional labour of their patients as well as to manage their own. In this context, physicians need to be able to empathise with their patients, be aware of their cultural backgrounds, and commit to social attention and social performance through the employment of their social intelligence. Therefore, health institutions must provide training programs for physicians that include social intelligence training through comprehensive learning programs that promote social performance, social concern, emotion regulation, and social information processing. These programs should include topics such as how to manage high sensitivity to emotional states along with training in strategies of emotional labour. These programs will positively affect relationships between physicians and patients and also improve physicians’ abilities to interact, collaborate, and adapt so that abuse of physicians can be reduced. Further, solutions to improve healthcare efficacy and patients’ understanding of the pressures experienced by physicians as well as the lack of capacity experienced by some hospitals can be developed. Moreover, hospitals must provide qualified social workers and psychologists on premises to help physicians deal with psychological and occupational pressures.

The best healthcare systems are those that provide patient-centred care—i.e., they make the patient the basis of the patient care process so that the needs of the patient and the results of their health screenings constitute the compass by which treatment is directed and decisions about the health sector are made. When patient-centred care is provided, the patient becomes an active participant regarding their health. This arrangement requires a distinct human relationship between the patient and medical staff, especially in the case of physicians, whose work entails not only physical but also emotional, psychological, and social care for patients; thus, physicians must develop their communication and social interaction skills (Berghout et al., 2015; Reynolds, 2009).

Limitations of the study

Despite this study providing important findings in the link between the relationship of emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism among physicians in the hospital workplace by using appropriate measures with a sample representative of the study population, this study had a limitation. The researcher’s inability to reach other governmental hospitals in the governorates of the Kingdom due to the curfew imposed as a result of the current COVID-19 pandemic, resulted in data collection being confined to three governmental hospitals in the Capital Governorate. The random sampling of physicians from multiple government hospitals at this level in Jordan could give more comprehensive results, leading to a better understanding of the causes of the abuse of physicians, and will provide added value in understanding the impact of emotional labour strategies for physicians in the patient care process. It may lead to an improvement in physicians’ well-being, efficacy of treatment, and a reduction in the number cases of abuse of physicians.

Conclusion

Physicians who exhibit higher levels of emotional labour will have higher social intelligence and lower levels of narcissism. In this context, deep acting as a strategy can be used by physicians to display emotions while engaging with patients to avoid emotional losses. Physicians need to recognise that their work requires emotional labour and an understanding of patients’ cultural backgrounds. Doing so will enable them to remain emotionally detached while increasing their social intelligence and optimising the practice of emotional labour in order to protect themselves from patients’ aggressive responses. The results of this study present some methods for improvement of the relationship between physicians and patients, which could help reduce the increasing cases of abuse of physicians in government hospitals. It would be beneficial for future research to be carried out in private hospitals with a specific focus on differences between hospitals in urban and rural areas.

References

Alexander GC, Humensky J, Guerrero C, Park H, Lowenstein G (2010) Brief report: physician narcissism, ego threats, and confidence in the face of uncertainty. J Appl Soc Psychol 40(4):947–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2010.00605.x

Al-hourani MA (2013) Tendencies for violence against doctors in public Jordanian hospitals: an attempt to understand this phenomenon in light of the doctor’s role. Univ Sharjah J Humanit Soc Sci 10(2):251–291

Alquisi S (2016) The violence causes and forms of violation on the medical staff in the government and private hospitals in Jordan. Jord J Soc Sci 9(1):93–108

Ames D, Rose P, Anderson C (2006) The NPI-16 as a short measure of narcissism. J Res Person 40(4):440–450. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.03.002

Asumah S, Agyapong D, Owusu N (2019) Emotional labor and job satisfaction: does social support matter? J Afr Bus 20(4):489–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1583976

Berghout M, van Exel J, Leensvaart L, Cramm JM (2015) Healthcare professionals’ views on patient-centered care in hospitals. BMC Health Service Res 15:385. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1049-z

Biron M, Veldhoven M (2012) Emotional labour in service work: psychological flexibility and emotion regulation. Hum Relat 65(10):1259–1282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726712447832

Blumer H (1969) Symbolic interactionism: perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Brotheridge CM, Lee RT (2003) Development and validation of the emotional labor scale. J Occup Organ Psychol 76(3):365–379. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903769647229

Bucknall V, Burwaiss S, MacDonald D, Charles K, Clement R (2015) Mirror on the ward, who’s the most narcissistic of them all? Pathologic personality traits in health care. CMAJ 187(18):1359–1363. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.151135

Cai R, Tang J, Deng C et al. (2019) Violence against health care workers in China, 2013–2016: evidence from the national judgment documents. Hum Resour Health 17:103. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-019-0440-y

Caligor E, Levy K, Yeomans F (2015) Narcissistic personality disorder: diagnostic and clinical challenges. Am J Psychiatr 172(5):415–422. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14060723

Carmi-Iluz T, Peleg R, Freud T et al. (2005) Verbal and physical violence towards hospital- and community-based physicians in the Negev: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res 5:54. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-5-54

Diefendorff JM, Croyle MH, Gosserand RH (2005) The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. J Vocat Behav 66(2):339–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.001

Dutton JE, Workman KM, Hardin AE (2014) Compassion at work. Ann Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 1(1):277–304. http://scholarship.sha.cornell.edu/articles/749

Erickson R, Grove W (2008) Emotional labor and health care. Sociol Comp 2(2):704–733. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2007.00084.x

Fields J, Copp M, Kleinman S (2006) Symbolic interactionism, inequality, and emotions. In: Turner, JH, JE Stets, JE (eds.). Handbook of the sociology of emotions. Springer, pp. 155–178. Springer

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Market Res 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Genç V (2013) The effects of emotional labor and emotional intelligence on job satisfaction of employees working in tourist companies in Alanya. (Unpublished Master’s Dissertation). Çanakkale: Çanakkale Onsekiz Mart University Graduate School of Social Sciences

Genc V, Genc SG (2018) Can hotel managers with social intelligence affect the emotions of employees? Cogent Bus Manage 5(1):1432157

Ghosh K (2018) Violence against doctors: a wake-up call. Ind J Med Res 148(2):130–133. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1299_17

Goffman E (1959) The persentation of self in everday life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday

Goffman E (1963) Behavior in public places: Notes on the social organization of gathering, New York: Free Press

Goffman E (1967) Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. Garden City, NY: Anchor Book

Grandey AA, Dickter DN, Sin HP (2004) The customer is not always right: customer aggression and emotion regulation of service employees. J Organ Behav 25:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.252

Grandey A, Diefendorff JM, Rupp D (2013) Emotional labor in the 21st century: diverse perspectives on emotion regulation at work. Routledge

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2019). Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective (8 edn.). Cengage Learning EMEA

Hair JF, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM, Mena JA (2012) An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J Acad Market Sci 40(3):414–433

Hirsch E (2007) The role of empathy in medicine: a medical student’s perspective. Virtual Mentor 9(6):423–427. https://doi.org/10.1001/virtualmentor.2007.9.6.medu1-0706

Hochschild A (1983) The managed heart: commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press

Indian Medical Association Press Release (2017) Majority of doctors fear violence and are stressed out reveals IMA study. 2017. Accessed on 22 May 2019, http://emedinews.in/ima/Press_Release/2017/July/1.pdf

Jeong JY, Park J, Hyun H (2019) The role of emotional service expectation toward perceived quality and satisfaction: moderating effects of deep acting and surface acting. Front Psychol 10:321. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00321

Jung HS, Yoon HH (2014) Moderating role of hotel employees’ gender and job position on the relationship between emotional intelligence and emotional labor. Int J Hospital Manage 43:47–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.08.003

Kerasidou A, Horn R (2016) Making space for empathy: supporting doctors in the emotional labour of clinical care. BMC Med Eth 17(8):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-016-0091-7

Kim HJ (2008) Hotel service providers’ emotional labor: the antecedents and effects on burnout. Int J Hosp Manage 27:151–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2007.07.019

Kinman G, Leggetter S (2016) Emotional labour and wellbeing: what protects nurses? Healthcare 4(89):1–12. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare4040089

Kong H, Jeon J (2018) Daily emotional labor, negative affect state, and emotional exhaustion: cross-level moderators of affective commitment. Sustainability 10(6):1967. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10061967

Kuhn W (1999) Violence in the emergency department. Managing aggressive patients in a high-stress environment. Postgrad Med 105(1):143–154. https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.1999.01.504

Lan YL, Yan YH (2017) The impact of trust, interaction, and empathy in doctor-patient relationship on patient satisfaction. J Nurs Health Stud, 2(2). https://doi.org/10.21767/2574-2825.100015

Larson E, Yao X (2005) Clinical empathy as emotional labor in the patient-physician relationship. J Am Med Assoc 293(9):1100–1106. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.9.1100

Lee JJ, Ok CM, Hwang J (2016) An emotional labor perspective on the relationship between customer orientation and job satisfaction. Int J Hospital Manage 54:139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.01.008

Leon J, Wise T, Balon R, Fava G (2018) Dealing with difficult medical colleagues. Psychother Psychosomat 87(1):5–11. https://doi.org/10.1159/000481200

Lin YW, Chang WP (2015) Physician emotional labour and job performance: the mediating effects of emotional exhaustion. J Health Manage 17(4):446–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0972063415606281

Mead G (1934) Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Ness GJ, House A, Ness AR (2000) Aggression and violent behavior in general practice: population-based survey in the north of England. Br Med J 320:1447–1448

Nwankwo BE, Obi TC, Sydney-Agbor N, Agu SA, Aboh JU (2013) Relationship between emotional intelligence and job satisfaction among health workers. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci 2(5):19–23. https://doi.org/10.9790/1959-0251923

Pandey J, Singh M (2016) Donning the mask: effects of emotional labour strategies on burnout and job satisfaction in community healthcare. Health Policy Plan 31(5):551–562. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czv102

Pervan M, Curak M, Pavic Kramaric T (2018) The influence of industry characteristics and dynamic capabilities on firms’ profitability. Int J Finan Stud 6(1):4

Psilopanagiot A, Anagnostopoulos F, Mourtou E, Niakas D (2012) Emotional intelligence, emotional labor, and job satisfaction among physicians in Greece. BMC Health Servic Res 12(1):463. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-463

Pugh SD, Diefendorff JM, Moran CM (2013) Emotional labor: organization-level influences, strategies, and outcomes. In: Grandey AA, Diefendorff JM, Rupp DE (eds.) Emotional labor in the 21st century: diverse perspectives on emotion regulation at work. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, pp. 199–221

Ravikumar R, Rajoura OP, Sharma R, Bhatia MS (2017) A study of emotional intelligence among postgraduate medical students in Delhi. Cureus 9(1):e989. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.989

Reddy IR, Ukrani J, Indla V, Ukrani V (2019) Violence against doctors: a viral epidemic? Indian J Psychiatr 61(Suppl 4):S782–S785. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_120_19

Reynolds A (2009) Patient-centered care. Radiol Technol 81(2):133–147

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker J-M (2015). SmartPLS 3 [Computer software]. SmartPLS GmbH. http://www.smartpls.com

Sarstedt M, Hair Jr JF, Cheah JH, Becker JM, Ringle CM (2019) How to specify, estimate, and validate higher-order constructs in PLS-SEM. Australas Market J (AMJ) 27(3):197–211

Scheff T (2014) Role-taking, emotion and the two selves. Can J Sociol 39(3):315–329. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjs20421

Shott S (1979) Emotion and social life: a symbolic interactionist analysis. Am J Sociol 84(6):1317–1334. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2777894

Silvera DH, Martinussen, Dahl TI (2001) The Tromso Social Intelligence Scale, a self-report measure of social intelligence. Scand J Psychol 42:313–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00242

Thorndike EL (1920) Intelligence and its use. Harper’s Magazine 140:227–235

Turner JH, Stets, JE (2005). The sociology of emotions. Cambridge University Press

von Scheve C (2012) Emotion regulation and emotion work: two sides of the same coin? Front Psychol 3:496. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00496

Wharton A (2009) The sociology of emotional labor. Annu Rev Sociol 35:147–165. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115944

Yagil D (2008) The service providers. Palgrave Macmillan

Acknowledgements

I thank Mr. Shahedul Hasan, Department of Marketing, University of Dhaka for the review and audit of the statistical analysis. I would also like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for help with English language editing. The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alsawalqa, R.O. Emotional labour, social intelligence, and narcissism among physicians in Jordan. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 174 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00666-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00666-w