Abstract

Governments worldwide have intensified their efforts to institutionalize policy evaluation. Still, also in organizations with high evaluation maturity, the use of evaluations is not self-evident. As mature organizations already meet many of the factors that are commonly seen to foster evaluation use, they constitute an interesting research setting to identify (combinations of) factors that can make a key difference in minimizing research waste. In this article, we present an analysis of the use of evaluations conducted between 2013 and 2016 by the Policy and Operations Evaluation Department (IOB) of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a typical case of relatively high evaluation maturity. Methodologically, we rely on Qualitative Comparative Analysis as an approach that is excellently suited to capture the causal complexity characterizing evaluation use. The analysis provides useful insights on the link between knowledge production and use. We highlight the relevance of engaging policy makers in developing the evaluation design, and fine-tune available evidence as to what is perceived a good timing to organize evaluations. Contrary to existing research, we show that the political salience of an evaluation does not matter much.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parallel with the diffusion of the evidence-based policy mantra, the attention for policy evaluations has risen dramatically in recent decades. In their quest for more efficient, effective and democratic policy decisions, governments worldwide have intensified their efforts to institutionalize policy evaluation (Jacob et al., 2015; Pattyn et al., 2018). Establishing a supportive evaluation infrastructure, however, is not a guarantee that evaluations are also used. Even in settings scoring relatively high on evaluation institutionalization or maturity indices (Furubo et al., 2002; Varone et al. 2005; Jacob et al., 2015; Stockmann et al., 2020), there is often much ‘research waste’ (Oliver and Boaz, 2019). In this article, consistent with our conceptualization of policy evaluation (see below), research waste refers to evaluation findings which do not provide useful knowledge for decision makers or which are not recognized as doing so. Research waste, or evaluation waste in particular, can lead to huge amounts of public money being misspent (Glasziou and Chalmers, 2018; Grainger et al., 2020).

When it comes to understanding the (non-)use of evaluations, a plethora of facilitators and barriers can be identified in evaluation discourse. Common to the practitioner-oriented nature of the field, much of the evidence is of anecdotal nature. Although anecdotal evidence as such is empirically valuable, it makes it particularly difficult to systematically draw lessons across individual evaluations (Ledermann, 2012, p. 159). While evidence use will never be straightforward in the reality of complex and messy decision making (Oliver and Boaz, 2019, p. 3), this may not discourage us from collecting systematic insights on evaluation use in particular contexts. In this article, we present the results of a systematic comparison of evaluation (non-) use in a typical case (Seawright and Gerring, 2008) of high evaluation maturity, but where evaluation use is neither self-evident. With high evaluation maturity, we refer to a context where significant resources are spent in producing high quality evaluations, and where an explicit concern exists for evaluation use. Evaluation mature organizations by definition already meet many of the factors that are commonly seen to foster evaluation use. Knowing which (combinations of) conditions can account for evaluation (non-)use in such setting can help identifying ‘critical change makers’, which can also be relevant in other contexts. As such, we aim to contribute to the broader research agenda on the issue, outlined by Oliver and Boaz (2019).

Empirically, the study focuses on the (non-)use of eighteen evaluations conducted in a time span of three years by the Policy and Operations Evaluation Department (IOB) of the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Netherlands ranks relatively high on the above-mentioned evaluation maturity and institutionalization indices (Jacob et al., 2015). And within the country, IOB is one of the frontrunner organizations when it comes to policy evaluation practice (Klein Haarhuis and Parapuf, 2016). In the past decade, the organization has also taken several initiatives to actively promote evaluation use (see below). This makes it a particularly interesting case.

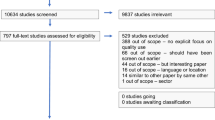

The research proceeded stepwise. First, we conducted an extensive screening of the evaluation literature to identify the conditions that could potentially account for evaluation use. Second, via desk research, interviews, and a survey with evaluators and policy makers, we investigated which conditions held relevance for the case of IOB. Third, by means of Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA), we analyzed which (combinations of) condition(s) are necessary and/or sufficient for evaluation use. QCA as a method is excellently suited to capture the causal complexity characterizing evaluation use.

The article is structured as following: In the theoretical framework, we describe the results of the literature screening for barriers and facilitators for evaluation use, and we explain our conceptual stance. Next, we introduce our research design, and present our case. We continue with the presentation and discussion of the findings. In the conclusion, we reflect on the theoretical and practical relevance of the results.

Theoretical framework

Barriers and facilitators for evaluation use: literature review

This study is about identifying the (combinations of) factors that influence evaluation use, through a systematic analysis of evaluations conducted by IOB. In the literature on evaluation use, one can find a multitude of factors that relate to the use of evaluations in public sector organizations. The table below (Table 1) lists the result of a screening of relevant texts that address factors contributing to evaluation (non-)use. We proceeded stepwise: first, we started from well-known and well-cited articles and books in the evaluation field discussing evaluation use. In these texts, we screened which sources were cited, and which sources cited them in turn. Second, we did a thorough search of Web of Science and the SAGE-database and JSTOR-database, using key words as ‘evaluation use’ and ‘utilization of evaluation’. Third, we screened existing literature reviews on evaluation use to identify any other relevant texts.

In the table, we specify whether the texts are of theoretical/conceptual or empirical nature, and detail to which type of use each factor holds relevance (if mentioned). We also state whether the factor was found to have (or expected to be) a negative (‘barrier’) or positive relationship (‘facilitator’) with use. We grouped the factors along several dimensions, staying close to the original labels used in the literature. As such, we distinguish between factors that concern the involvement of policy makers; political context; timing of the evaluation; key attributes of the evaluation/report; characteristics of the evaluator; policy maker characteristics; and characteristics of the public sector organization which commissioned an evaluation.

It would exceed the scope of this contribution to discuss all individual studies in depth. Neither do we claim that our overview is exhaustive. As may be clear, however, the analysis supports the diagnosis of a field without a consistent research agenda on evaluation use. True, a broad diversity of factors is discussed in evaluation literature, but there is great imbalance in the amount of available empirical evidence across factors. Also, there is strong diversity in how individual elements have been conceptualized and operationalized. We further highlight the fact that many studies are not explicit in the type of use being studied. It is noteworthy as well that factors impeding use are usually not directly addressed; overall studies are more focused on the factors fostering use. Finally, and as mentioned before, there is little information on how individual factors interact with each other (Johnson et al., 2009, p. 399). By zooming into a setting with high evaluation maturity, we aim to identify those combinations of factors that have the potential to make a key difference.

Instrumental evaluation use

In line with OESO-DAC (1991) and consistent with the definitions applied by IOB, our case organization, we conceive a policy evaluation as “an assessment, as systematic and objective as possible, of an on-going or completed project, programme or policy, its design, implementation and results. The aim is to determine the relevance and fulfillment of objectives, developmental efficiency, effectiveness, impact and sustainability. An evaluation should provide information that is credible and useful, enabling the incorporation of lessons learned into the decision-making process of both recipients and donors”. As can be remarked, the definition assumes a fairly traditional approach to a policy cycle, but is useful as an analytical heuristic. Most importantly, it highlights the usefulness of evaluation for decision-making. As to the latter, we do not make a distinction between accountability and learning, as the main (rational) evaluation purposes (Vedung, 1997). Not only are the two hard to distinguish methodologically. The evaluation goal can also change throughout the evaluation lifecycle.

Of the many approaches to evaluation use, we focus on instrumental use, consistent with the majority of empirical research on the issue, and as such in an effort to build up more systematic cumulative knowledge on the issue. We conceptualize instrumental use as the use of the evaluation for direct information or policy decision making (Alkin and Taut, 2003; Ledermann, 2012), regardless of whether the use is intended or unintended. In our understanding, use does not necessarily involve an actual change to the policy, but the knowledge gained from the evaluation should at a minimum inform decision making about the policy. The knowledge should neither be novel per se; it is possible that the knowledge was already known before, but that the evaluation constituted the catalyst for action.

As to the timing of use, we focused on immediate and so called end-of-cycle use (Kirkhart, 2000), referring to use that happened during or closely following the evaluation study. Of course, we do not rule out that use can happen at a (much) later time (Kirkhart, 2000; Feinstein, 2002). One can assume, however, that the urgency to act on the findings will be highest immediately following the evaluation study. Also, the decision to focus only on studies that were not older than three years at the time of data collection (to make sure that respondents could still recall use), put empirical constraints on investigating use at a later point in time.

We conceived instrumental use to be ‘present’ (see below) if at least one major policy decision was influenced significantly by the evaluation. Such policy decisions can concern the termination or continuation of the policy; an important strategic change in the policy with consequences at the operational level; or a major change in funding. To be clear, in our perspective, instrumental use can but does not necessarily have to be written down (Leviton and Hughes, 1981, p. 530).

Research design

Case: policies and operations evaluations department (IOB) in the Netherlands

As mentioned, we focus on evaluations conducted by/for the Policies and Operations Evaluations Department (IOB) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the Netherlands. IOB is part of the Ministry but operates independently from the policy department and has its own budget. The organization was established in the 1970s, and charged with the mission to study the effects of Dutch governmental development aid. In general, IOB aims to conduct high-quality evaluations that should serve learning and accountability purposes (Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 2009). Policy makers in the Ministry’s policy department constitute the main target group. At present, it can be said that IOB has an established reputation and adequate experience with evaluation research. As mentioned above, evaluation use has been a priority for the organization since years. In 2009, for instance, the Minister of Development Cooperation established an advisory panel of external experts, particularly with the aim to assess and improve the usability and use of evaluations for policy and practice. The panel only ceased existence in 2014 (Klein Haarhuis and Parapuf, 2016). In Dutch Parliament, IOB evaluations get quite some attention, where even international comparisons on the institutionalization of evaluations explicitly referred to (Jacob et al., 2015, p. 21).

Data collection

The actual data collection for the research took place in June and July 2016. We selected the entire sample of 20 evaluations that were (at the time) most recently conducted for IOB. The evaluations were completed and sent to Parliament between 2013 and 2016. Spanning a period of 3 years, they can be conceived as representative for IOBs evaluation practice. Eventually, with some targeted respondents not being available, we proceeded with 18 evaluations for a more in depth analysisFootnote 1. According to the evaluations’ Terms of Reference, most had a duration of approximately one year, with five months as the lower limit and 24 months as the upper limit. All evaluations were made public. Of the 18 evaluations our study included 7 so-called policy reviewsFootnote 2 (i.e., systematic reviews), 5 evaluations of programmes or activities of (semi) public organizations, and 6 evaluations of thematic and regional policies. Just one evaluation concerned ongoing policy, the others were all ex post evaluations. Substantively, 10 of the evaluations focused on international development policy, the other related to foreign affairs, such as human rights.

The total number of 18 evaluations allowed us to gain sufficient ‘intimacy’ with the cases, while also holding potential for systematic cross-case analysis (Rihoux and Lobe, 2009, p. 223). Data collection consisted of three main sources, which we triangulated to have a reliable picture of each evaluation. To begin with, we studied all relevant documentation relating to the evaluations (such as the Terms of Reference, interim reports, final evaluation report and the Ministerial response following the evaluation). Next, we held a minimum of two interviews for each evaluation, one with the evaluator(s) and one with the policy maker who was most closely involved in the evaluation and who was the main contact person for the evaluation team. In all but one case, we could interview the so-called IOB ‘inspector’ and the IOB researcher in charge of the evaluation. In addition, we sent a questionnaire to other policy makers who were having a substantial role in the evaluation. The latter being for instance policy makers who had partaken in the reference group, who served as a respondent in the evaluation, or who were responsible for writing the policy response on the evaluation.

Identifying conditions with most explanatory potential

On the basis of the triad of sources, only five evaluations qualify as being used in an instrumental way. This is already worth highlighting: also in the evaluation mature setting of IOB, not half of the evaluations are instrumentally used. The observation tends to support the criticism that evidence-based policy is often unrealistic and relying on a too rational and linear approach to policy making (e.g., Sanderson, 2006; Strassheim and Kettunen, 2014). Still, with Carey and Crammond (2015, p. 1021), we argue that we should be careful not to throw the baby out with the bathwater. In five cases, the evaluations were indeed used in a tangible way, prompting the question what distinguishes them from the rest.

To solve this complex puzzle, the above longlist of factors (Table 1) explaining use served as our starting point. We only scrutinized those conditions that concern the organizational level. After all, at the national level policies are very rarely decided upon by one person alone (Weiss, 1998). As such, explanatory attributes merely relating to characteristics of individual civil servants fell out of the scope of this study. Taken this altogether, we ended up with a series of 18 factors, grouped along 6 categories, which display strong parallels with the categories of our literature review. The categories concern:

-

1.

Contact between evaluator and policy makers,

-

2.

Political context,

-

3.

Timing of the study,

-

4.

Evaluation characteristics,

-

5.

Evaluator characteristics,

-

6.

Characteristics of the policy department.

The overview of all factors per category can be consulted in the supplementary materials. We also list which measures we used to operationalize each of the factors in a qualitative way. During the data collection process, it turned out that some factors proved not relevant for further analysis. For a substantial number of factors, we observed no or only very little variation across the evaluations. This is largely to be interpreted in light of IOB’s evaluation maturity. For instance, for all factors relating to the ‘contact between evaluator and policy maker’, evaluations scored quasi-identical. IOB established a certain routine in this respect, which makes that evaluation processes occur in relatively similar ways in terms of the ‘frequency of contact between evaluator and policy makers’, the ‘formality of the contact’, as well as for ‘timing of contact’. Similar observations apply to ‘evaluation quality’ or ‘readability of the evaluation report’, which were perceived as almost constant across the cases. IOB developed a stringent quality assurance system, resulting in the observation that all evaluations are seen as of relatively good quality and well-written. Also ‘the credibility of evaluators’ was perceived as generally high across the board. These observations should not be interpreted wrongly, as if these factors should be given less attention to when engaging in policy evaluations. However, for the case of IOB, with a strong evaluation tradition, they are not sufficient to account for differences in evaluation use.

Other than these relatively stable factors, we excluded a few others which proved difficult to measure in a reliable way, at least with our data collection strategy. The ‘feasibility of recommendations’ is one of them. In practice, evaluations included a mixture of recommendations of which some were deemed feasible and others not. Also, respondents struggled to indicate what they conceived feasible. In many instances, it was neither possible to analytically distinguish the feasibility of recommendations from the dependent (outcome) variable. In the same vein, we could not obtain reliable findings when investigating whether it was the evaluator and/or the policy maker who took the initiative for contact. Respondents could often not remember who actually initiated the contact, and/or evaluators and policy makers frequently gave inconsistent responses.

Importantly, QCA requires researchers to craft an explanatory model based on both theoretical insights and empirical information on these variables in the context of specific cases (Marx and Dusa, 2011, p. 104). Also, in QCA model building, a good ratio between conditions and cases is essential to obtain valid findings (Schneider and Wagemann, 2010). With 18 cases, it is advisable to limit the model to four conditions (Marx and Dusa, 2011, p. 104). From the data collection the four factors below appeared most relevant in case of the IOB, and qualify as potentially of strong importance in understanding instrumental evaluation use:

-

- the political salience of the evaluation (cfr. Ledermann, 2012; Barrios, 1986, p. 111). While many possible approaches exist to measure political salience, we opted for a conceptualization (see Table 2) derived from conversations with policy makers before the data collection phase. As we focused on the use of the evaluations in making policy decisions, we deliberately accounted for this policy makers’ perspective.

-

- timing of the evaluation process (Bober and Bartlett, 2004, p. 377; Boyer and Langbein, 1991, p. 527; Rockwell et al., 1990, p. 392; Shea, 1991, p. 107). While most studies usually approach timing by asking policy makers whether the evaluation was on time/too early/ too late, we take a more objective stance. We analyze in particular whether it matters if the evaluation runs in parallel to the policy formulation process in which new policy measures are drafted or old ones are revised.

-

- whether the study generates novel knowledge, not previously known to policy makers (Ledermann, 2012, p. 173; Johnson et al., 2009, p. 385).

-

- clear interest in the evaluation among the main policy maker(s) involved (see e.g., Johnson et al., 2009; Leviton and Hughes, 1981; Patton et al., 1977, Preskill et al., 2003).

While all these factors have been given considerable attention in the evaluation literature, evidence about their relevance for evaluation use if often mixed, and frequently running in opposite causal directions. The question is then whether more causal clarity can be obtained by unraveling how these factors interact with each other, and whether different combinations can be identified?

Qualitative comparative analysis

Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) as a method lends itself very well to study such causal complexity. By systematically comparing evaluations as configurations of conditions (i.e., factors), we can search for prevalent patterns and identify redundant conditions that do not seem to make a difference in explaining evaluation use. As a set-theoretic approach, QCA aims to identify so-called ‘necessary’ and ‘sufficient’ (combinations of) conditions. Will a condition (or a combination of conditions, i.e., configuration) be sufficient, the outcome should appear, whenever the condition is present. A (combination) of condition(s) found as necessary implies that it will always be present/absent whenever the outcome is present/absent (Pattyn et al. 2019).

QCA comes with assumptions of equifinality, conjunctural causation, and asymmetric causality. Equifinality means that there are usually multiple causal combinations of factors leading to a particular outcome, i.e., the use of policy evaluations. Multiple conditions can be sufficient for an outcome, of which none is actually necessary. Conjunctural causality refers to the idea that a combination of factors, instead of a single factor, might cause an outcome to occur. Asymmetric causality, finally, implies that if the presence of a particular (combination of) conditions is relevant for the outcome, its absence is not necessarily relevant for the absence of the outcome. To compare the cases in a systematic and formal way, QCA uses Boolean logic. The present research relied on the original crisp set version of QCA. Crisp set QCA requires to ‘calibrate’ (code) all conditions (and the outcome) in binary terms 1 and 0, expressing qualitative differences in kind. Conditions assigned a score of 1 should be read as present, while a score of 0 is to be regarded as absent. To arrive at this score, we largely applied the step-wise approach outlined by Basurto and Speer (2012). They describe how to transform qualitative data in QCA. First, and as mentioned, we developed measures to operationalize each of the conditions in a qualitative way. On this basis, we collected data on each measure using documents, interviews and the survey. We subsequently summarized all information for each evaluation, and checked this for consistency. This helped us to define the crisp-set values, 1 or 0. In the last step, we assigned the values of the conditions for each evaluation. Table 2 explains how we calibrated each of the conditions. A condition is absent if the evaluation did not meet this conceptualization.

The Supplementary Materials include the so-called ‘truth table’, which lists all possible configurations leading to a particular outcome, i.e., use or non-use. More extensive ontological and technical details about the method and its procedures can be found in specialized textbooks such as Ragin (1987, 2000, 2008), Rihoux and Ragin (2009), and Schneider and Wagemann (2012).

Findings

Prior to searching for the combinations of conditions being sufficient for use or non-use in the IOB setting, QCA practice requires to verify whether there are any necessary conditions for use, or non-use.Footnote 3 Table 3 presents the results of the analysis of necessity, restricted to the four conditions that we identified as potentially explanatory powerful.

As becomes clear, in all IOB evaluations which qualify as being used, the evaluation took place in parallel to the drafting process of a new policy [Timing=Present]. In these evaluations, policy makers also clearly expressed interest [Interest=Present]. Yet, while ‘necessary’ strictly speaking, both conditions are to some extent ‘trivial’, as they are not unique to the ‘success’ cases only.Footnote 4 Also in the instances where the evaluations were not used, these conditions are often present. Interestingly though, we cannot identify any necessary conditions for ‘non-use’.

Table 4 presents the results of the analysis of sufficiencyFootnote 5 for the presence of evaluation use. We can identify one ‘path’ being associated with evaluation use, which includes the necessary conditions ‘Timing’ and ‘Interest of policy makers’, but also highlights the importance of novel knowledge revealed by the evaluation. In formal terms, this solution can be presented as (with * referring to logical ‘AND’; and capital letters implying the ‘presence’):

TIMING * NOVEL KNOWLEDGE* INTEREST → USE

Of the five evaluations that are indeed used, four evaluations are covered by this ‘solution’, to put it in QCA terms. Importantly, of the cases that are not used, none displays this combination of conditions.

When turning to the analysis of the absence of instrumental use, the causal picture is more complex, with three different paths that can be distinguished (Table 5).

In formal terms, this can be presented as (‘+’ to be read as ‘logical OR’; and small letters reflecting the absence of conditions):

timing * novel knowledge + POLITICAL * novel knowledge * interest + timing * INTEREST → use

Altogether, these three paths cover ten of the thirteen evaluations that did not result in instrumental use. Again, there are no evaluations among the ‘successful’ cases that share any of these configurations.

Discussion

Of the longlist of potential barriers and facilitators for evaluation use that we started from, we identified four conditions with potentially strong explanatory power for the mature evaluation setting of IOB: the timing of the evaluation, its political salience, whether policy makers show clear interest in the evaluation, and whether the evaluation presents novel knowledge. Of these conditions, an appropriate timing of the evaluation, and clear interest among policy makers prove ‘necessary’ for evaluation use to take place, which is a first important observation. As for timing, our study further highlights the relevance of having the evaluation running in parallel to the policy formulation process. Yet, the mere presence of these two conditions is not sufficient for evaluation use. Whether the evaluation is picked up will also depend on the novelty of the knowledge being generated, as we have shown in our analysis. For four of the five evaluations that were indeed used, these three conditions together turn out to be sufficient for use to take place. If these conditions are met, it does not seem to matter whether the issue is perceived as politically salient.

All three facilitators can clearly strengthen each other and are not fully independent: policy makers with clear interest in the evaluation will be incentivized to ask specific questions during the evaluation process, which increases the chances of novel knowledge being generated. In turn, it can be speculated that a policy maker’s interest will also depend on the timing of the evaluation. If the evaluation takes place while policy makers are dealing with the revision of existing policy, or when drafting new policy, there will be more reason to engage in the evaluation, and to ask specific questions. It is an encouraging observation as well that political salience matters less, precisely because this an element that is often beyond control of policy makers and evaluators.

More insights can be obtained from analyzing the cases that were less successful in terms of instrumental use. The causal picture is more complicated for these evaluations, with no less than three different ‘recipes’ for non-use. We could not identify any necessary conditions for non-use. A first path revolves around the absence of novel knowledge, and an inappropriate timing of the evaluation. Logically, when policy makers are not working on new policy or major policy changes, there will be less opportunity to make use of the evaluation findings, especially if the evaluation neither generates novel knowledge. Empirically speaking, this first path has most explanatory power. In a second path, the absence of novel knowledge returns again as a major barrier for use in a politically salient setting, in combination with a lack of evaluation interest among policy makers. Again, when there is no new knowledge generated, and if policy makers do not show genuine interest, there is hardly any reason for the evaluation being used. A third path, applying to two empirical cases, confirms once more the importance of timing: even if policy makers have some interest in the evaluation, but if the evaluation does not take place at the right timing, there may not be possibilities for evaluation use. In at least one of the cases, it was explained that the policy makers were intrinsically interested in the evaluation results, but that management was not eager to act upon the evaluation. In other studies, focusing on reasons behind evaluation inactivity (Blinded for review), it was already shown that managerial attitudes to evaluation are an important aspect to consider.

Conclusion

In the evaluation literature, one can identify a plethora of facilitators and barriers for evaluation use. It can be assumed, however, that such facilitators/barriers will not be equally at play in all organizations. Especially in organizations with a strong evaluation tradition, there are usually built-in guarantees to make sure that evaluations reach certain minimum quality standards. Still, also in such organizations, as the IOB case shows, it is not self-evident that evaluations are indeed used. On the contrary, of the eighteen evaluations that we studied, only five were perceived as being used, at least in an instrumental way. As such, this confirms that policy making is highly complex, and that it would be naive to think that evidence would be used in a linear and rational way (Strassheim and Kettunen, 2014). This will even more apply to a wicked policy setting as development cooperation, where interventions tend to be complex, and multiple stakeholders often hold competing interests (Holvoet et al., 2018). Policy evaluation will always remain an intrinsic political undertaking (Weiss, 1993), irrespective of the evaluation maturity of a public sector organization.

Of course, future research ideally verifies whether our findings hold true for other evaluation mature settings, and in settings characterized by a knowledge regime, different from the Dutch consensus-style tradition (Jasanoff, 2011; Strassheim and Kettunen, 2014). A more in depth engagement with the type of knowledge regime could also help understanding what makes an evaluator being perceived as reliable, or results credible. In our study we did not open this blackbox. Also, while we scrutinized a relatively long range of explanatory factors for evaluation use, a more extensive review beyond the disciplinary boundary of the evaluation field would potentially yield other relevant factors. Similarly, we primarily focused on the point of view of civil servants, leaving aside politicians’ perspectives on evaluation use or other political variables. Finally, it could be valuable to consider other policy fields. Development cooperation is one of the fields where one can typically find a lot of evaluation practice, and where internally independent evaluation units, such as IOB, often have a key role in generating evaluations (Stockmann et al., 2020). This makes it a rather particular evaluation setting.

These limitations notwithstanding, the analysis provides useful insights on the link between knowledge production and use, and points at important elements to consider in deciding who to involve in the evaluation process and when evaluations are ideally set up to minimize research waste (Oliver and Boaz, 2019). The contribution highlights the importance of interest among policy makers for the evaluation, and engaging them in the evaluation process. Providing policy makers the opportunity to suggest evaluation questions seems key in this regard. As mentioned by one of our respondents, the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs is characterized by a fast-changing policy setting, which leaves little time for reflection and learning among policy makers. Under these circumstances, it is no big surprise that an evaluation will only be used when the main policy maker(s) is really dedicated to doing so. In the same vein, we observed that ex post evaluations are perceived as timely, especially when taking place simultaneously with drafting new/changed policy measures. As such, our research fine-tunes available evidence (Leviton and Hughes, 1981; Johnson et al., 2009) that demonstrates the importance of timing, but which did not detail what an appropriate timing is. Other than this, and especially interesting in light of the political nature of evaluation, the analysis shows that the use of evaluations is not hindered, but neither promoted by an issue being political salient. As political salience that is less malleable by policy makers, this in itself is an encouraging observation, and puts previous research on the issue in a different light (e.g., Ledermann, 2012; Barrios, 1986).

Methodologically, by relying on QCA, we could reveal how these factors precisely interact. True, given the relatively low number of cases, we were constrained in the number of conditions that we could include in the analysis. Nonetheless, via the method, we could identify multiple paths to use or non-use which echoes the multiple conjunctural nature of evidence utilization (Ledermann, 2012). Also, the analysis confirmed that evidence use, and non-use is best to be conceived from a causally asymmetric approach, with different explanations being accountable for use, and for non-use. While the barriers and facilitators’ approach can be conceived as reductionist in itself, it can help to get a systematic overview, and to identify certain patterns across research and evaluation studies. Given its ontological characteristics, the method also has much potential, we believe, to advance the broader research agenda on evidence use.

Data availability

The QCA ‘truth table’ generated and analyzed during this study can be consulted in the Supplementary Materials. A replication document can be achieved from the authors upon request.

Notes

The list of evaluations can be received from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, and after approval by IOB.

Policy reviews are mandatory reviews of policies conducted at least once every seven years. The specifications for this specific type of evaluation are laid down in the Regeling Periodiek Evaluatieonderzoek. https://wetten.overheid.nl/jci1.3:c:BWBR0040754¶graaf=2&artikel=3&z=2018-03-27&g=2018-03-27.

The QCA analysis has been conducted in R (packages QCA, QCA3; SetMethods).

The coverage score for timing is 0.56 and for interest 0.42. QCA denotes this as ‘low coverage’, or ‘trivial’ (Schneider and Wagemann, 2010, p. 144).

Conservative solution: we did not make any assumptions on the logical remainders, i.e., the combinations of conditions that are logically possible, but for which we do not have any empirical observations.

References

Alkin MC, Jacobson P, Burry J, Ruskus J, White P, Kent L (1985) A guide for evaluation decision makers. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

Alkin MC, Taut SM (2003) Unbundling evaluation use. Stud Education Eval 29:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-491X(03)90001-0

Balthasar A (2006) The effects of institutional design on the utilization of evaluation: evidenced using qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). Evaluation 12(3):354–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389006069139

Barrios NB (1986) Utilization of evaluation information: a case study approach investigating factors related to evaluation utilization in a large state agency (Doctoral dissertation, Florida State University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing)

Basurto X, Speer J (2012) Structuring the calibration of qualitative data as sets for qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). Field Methods 24(2):155–174

Bober CF, Bartlett KR (2004) The utilization of training program evaluation in corporate universities. Human Res Dev Quart 15(4):363–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrdq.1111

Boyer JF, Langbein LI (1991) Factors influencing the use of health evaluation research in Congress. Eval Rev 15(5):507–532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X9101500501

Carey G, Crammond B (2015) What works in joined-up government? An evidence synthesis. Int J Public Admin 38(13–14):1020–1029

Coryn CLS, Noakes LA, Westine CD et al. (2011) A systematic review of theory-driven evaluation practice from 1990 to 2009. Am J Eval 32(2):199–226. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010389321

Forss K, Cracknell B, Samset K (1994) Can evaluation help an organisation to learn? Eval Rev 18(5):574–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X9401800503

Furubo JE Rist RC Sandahl R (eds) (2002) International atlas of evaluation. Transaction publishers, New Jersey

Glasziou P, Chalmers I (2018) Research waste is still a scandal—an essay. BMJ 363:k4645

Grainger MJ, Bolam FC, Stewart GB, Nilsen EB (2020) Evidence synthesis for tackling research waste. Nat Ecol Evol 4(4):495–497. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1141-6

Greene JC (1988) Communication of results and utilization in participatory program evaluation. Eval Program Planning 11:341–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(88)90047-X

Feinstein ON (2002) Use of evaluations and the evaluation of their use. Evaluation 8(4):433–439

Hodges SP, Hernandez M (1999) How organisation culture influences outcome information utilization. Eval Program Planning 22:183–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(99)00005-1

Holvoet N, Van Esbroeck D, Inberg L, Popelier L, Peeters B, Verhofstadt E (2018) To evaluate or not: evaluability study of 40 interventions of Belgian development cooperation. Eval Program Planning 67:189–199

Jacob S, Speer S, Furubo JE (2015) The institutionalization of evaluation matters: updating the international atlas of evaluation 10 years later. Evaluation 21(1):6–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389014564248

Jasanoff S (2011) Designs on nature: science and democracy in Europe and the United States. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Johnson K, Greenseid LO, Toal SA et al. (2009) Research on evaluation use: a review of the empirical literature from 1986 to 2005. Am J Eval 30(3):377–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214009341660

Kirkhart KE (2000) Reconceptualization evaluation use: an integrated theory of influence. New Direct Eval 88:5–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ev.1188

Klein Haarhuis C, Parapuf A (2016) Evaluatievermogen bij beleidsdepartementen. Praktijken rond uitvoering en gebruik van ex post beleids-en wetsevaluaties. Cahier 2016-5. Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek en Documentatiecentrum. Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie, Den Haag

Ledermann S (2012) Exploring the necessary conditions for evaluation use in program change. Am J Eval 33(2):159–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214011411573

Leviton LC, Hughes EFX (1981) Research on the utilization of evaluations: a review and synthesis. Eval Rev 5(4):525–548. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X8100500405

Marra M (2004) The contribution of evaluation to socialization and externalization of tacit knowledge: the case of the World Bank. Evaluation 10(3):263–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389004048278

Marsh DD, Glassick JM (1988) Knowledge utilization in evaluation efforts: the role of recommendations. Knowledge 9(3):323–341. https://doi.org/10.1177/107554708800900301

Marx A, Dusa A (2011) Crisp-set qualitative comparative analysis (csQCA), contradictions and consistency benchmarks for model specification. Methodol Innovations Online 6(2):103–148. https://doi.org/10.4256/mio.2010.0037

Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2009) Evaluatiebeleid en richtlijnen voor evaluaties. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/brochures/2009/10/01/evaluatiebeleid-en-richtlijnen-voor-evaluaties. Accessed 17 Nov 2019

OESO-DAC (1991) Principles for the evaluation of development assistance. OECD, Paris

Oliver K, Boaz A (2019) Transforming evidence for policy and practice: creating space for new conversations. Pal Commun 60:10

Patton MQ, Grimes PS, Guthrie KM et al. (1977) In search of impact: an analysis of the utilization of federal health evaluation research. In: Weiss C (ed) Using social research in public policy making. Lexington Books, Lexington, pp 141–163

Pattyn V, Molenveld A, Befani B (2019) Qualitative comparative analysis as an evaluation tool: Lessons from an application in development cooperation Am J Eval 40(1):55–74

Pattyn V, Van Voorst S, Mastenbroek E, Dunlop CA (2018) Policy evaluation in Europe. In:Ongaro E, Van Thiel S (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Public Administration and Management in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp 577–593

Preskill H, Zuckerman B, Matthews B (2003) An exploration study of process use: findings and implications for future research. Am J Eval 24(4):423–442

Ragin CC (1987) The comparative method: moving beyond qualitative and quantitative strategies. University of California Press, Berkeley

Ragin CC (2000) Fuzzy-set social science. University Chicago Press, Chicago

Ragin CC (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Rihoux B, Lobe B (2009) The case for qualitative comparative analysis (QCA): adding leverage for thick cross-case comparison. In: Byrne D, Ragin CC (eds) The Sage handbook of case-based methods. Sage, London, pp 222–243

Rihoux B, Ragin CC (eds) (2009) Configurational comparative methods: qualitative comparative analysis (QCA) and related techniques. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Rockwell SK, Dickey EC, Jasa PJ (1990) The personal factor in evaluation use: a case study of steering committee’s use of a conservation tillage survey. Eval Program Planning 13:389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(90)90024-Q

Sanderson I (2002) Evaluation, policy learning and evidence-based policy making. Public Admin 80(1):1–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9299.00292

Sanderson I (2006) Complexity, ‘practical rationality’ and evidence-based policy making Policy Politics 34(1):115–132

Schneider CQ, Wagemann C (2010) Standards of good practice in Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and Fuzzy-Sets. Compara Sociol 9:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1163/156913210X12493538729793

Schneider CQ, Wagemann C (2012) Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: a guide to Qualitative Comparative Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Seawright J, Gerring J (2008) Case selection techniques in case study research: a menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Polit Res Quart 61(2):294–308

Shea MP (1991) Program evaluation utilization in Canada and its relationship to evaluation process, evaluator and decision context variables. Dissertation, University of Windsor

Shulha LM, Cousins JB (1997) Evaluation use: theory, research, and practice since 1986. Eval Practice 18(3):195–208

Stockmann R, Meyer W, Taube L (2020) The Institutionalisation of evaluation in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan

Strassheim H, Kettunen P (2014) When does evidence-based policy turn into policy-based evidence? Configurations, contexts and mechanisms. Evidence Policy 10(2):259–277

Turnbull B (1999) The mediating effect of participation efficacy on evaluation use. Eval Program Planning 22:131–140

Varone F, Jacob S, De Winter L (2005) Polity, politics and policy evaluation in Belgium. Evaluation 11(3):253–273

Vedung E (1997) Public policy and program evaluation. Routledge

Weiss CH (1993) Where politics and evaluation research meet. Am J Eval 14(1):93–106

Weiss CH (1998) Have we learned anything new about the use of evaluation? Am J Eval 19(1):21–33

Widmer T, Neuenschwander P (2004) Embedding evaluation in the Swiss Federal Administration: Purpose, institutional design and utilization. Evaluation 10(4):388–409.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible through funding support of the KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pattyn, V., Bouterse, M. Explaining use and non-use of policy evaluations in a mature evaluation setting. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 7, 85 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00575-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00575-y

This article is cited by

-

Evidence for policy-makers: A matter of timing and certainty?

Policy Sciences (2024)