Abstract

Over the past four decades, the humanities have been subject to a progressive devaluation within the academic world, with early instances of this phenomenon tracing back to the USA and the UK. There are several clues as to how the university has generally been placing a lower importance on these fields, such as through the elimination of courses or even whole departments. It is worth mentioning that this discrimination against humanities degrees is indirect in nature, as it is in fact mostly the result of the systematic promotion of other fields, particularly, for instance, business management. Such a phenomenon has nonetheless resulted in a considerable reduction in the percentage of humanities graduates within a set of 30 OECD countries, when compared to other areas. In some countries, a decline can even be observed in relation to their absolute numbers, especially with regards to doctorate degrees. This article sheds some light on examples of international political guidelines, laid out by the OECD and the World Bank, which have contributed to this devaluation. It takes a look at the impacts of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities, both inside and outside of the university, while assessing the benefits and value of studying these fields. A case is made that a society that is assumed to be ideally based on knowledge should be more permeable and welcoming to the different and unique disciplines that produce it, placing fair and impartial value on its respective fields.

Introduction

In August 2017, the World Humanities Conference took place in Liège, Belgium. The theme was Challenges and Responsibilities for a Planet in Transition, and it was organized in cooperation with UNESCO. The rationale for this conference can be summarized as follows:

“The humanities were at the heart of both public debate and the political arena until the Second World War. In recent years their part was fading and they have been marginalized. It is crucial to stop their marginalization, restore them and impose their presence in the public sphere as well as in science policiesFootnote 1”

I participated in this event and it gave me hope that it would be possible to reverse the general trend of devaluating the humanities, something that has been going on since the early 1980s, namely in the UK and in the USA (Costa, 2016). Such a phenomenon has coexisted with an acceleration in globalization and a widespread rise of neoliberalism, two trends which have been gradual and simultaneous in their origins (Heywood, 2014). In regard to the growth of neoliberalism, while in the 1980s only four countries had what could be reasonably categorized as neoliberal governments (Chile, New Zealand, the UK and the USA), at the beginning of the 21st century that number had multiplied all around the world (Peck, 2012).

This marginalization of the humanities has been a gradual process that manifested itself at different times throughout the countries in which it can be observed. A global approach was used for studying this process (Costa, 2016), along with available OECD data which consisted of a subset of thirty countries and recorded the period between 2000 and 2012Footnote 2. Under these circumstances, “graduates by field of education”Footnote 3 is arguably one of the few relevant indicators that we can establish. On analysing it, one can conclude that despite some variance in tendencies for each individual nation, there is an overall shift that allows us to confidently corroborate such a devaluation when we compare figures for the year 2000 with those of 2012. This approach was further complemented with the analysis of case studies and existing academic literature on the topic (Costa, 2016).

With that in mind, it seems paradoxical that in a so-called knowledge society, one that should be ‘nurtured by its diversity and its capacities’ (UNESCO, 2005, p.17), not all knowledge fields would be valued in an equitable manner. So why does it happen and why namely at the expense of the humanities? Conversely, what are the reasons for looking at the humanities in a more positive light? These reasons have long been known, but can nowadays lack sufficient recognition. The goal of this comment is to address these questions.

The way to find the answers to these discussion points begins with an analysis of political documents written within the framework of international organisations such as the World Bank and the OECD during the transition into the 21st century. This analysis identifies some political guidelines that have plausibly influenced the global shift in the number of graduates by field of education occuring between 2000 and 2012. Afterwards, we take a look at the impact that these guidelines have had both within and outside of the University. Once done, we reflect on the benefits of studying the humanities and on the complementarity of the various knowledge fields within society.

The political constraints of the devaluation of the humanities in an academic context

Taking into account the already long history of the University, its most recent transformation has been marked by the principles of neoliberalism and the pace of this change has increased since 1998 (Altbach et al., 2009). It is in this particular institutional context that the devaluation of the humanities has been taking place. If we pay attention to the general guidelines that have been at the core of this paradigm shift, we can see that the humanities have been confronted not so much with a direct and explicit denial of their benefits, but with the exalting of skills and traits strongly connected to other knowledge fields, such as business administration. This reasoning is based on the following analysis of some specific documents that are enlightening examples of this occurrence.

At The World Conference on Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century, organized by UNESCO in 1998, in Paris, two talks expanded on how the University was already undergoing a process of transformation—one from a practical point of view, and the second from a conceptual one.

In the first talk, titled The Financing and Management of Higher Education: a Status Report on Worldwide Reforms (Johnstone et al. 1998), the authors explain how the World Bank implemented its political agenda in order to reform the University throughout the 90s in several countries. A political decision to reduce public investment fundamentally altered the financial and managerial scenarios of the University. A result of this was that the academic sector was steered towards the markets, with an explicit mention in the report that this shift was meant to align with neoliberal principles.

The consistency of this reform has been hailed as remarkable by the cited authors. It has followed similar patterns across all countries independently of existing differences between them with regards to political and economic systems, states of industrial and technological development, and the structuring elements of the higher education system itself.

In the other talk, titled Higher Education Relevance in the 21st Century, Michael Gibbons (1998), counselor to the World Bank, affirms the urgency of a new paradigm for the University, and theorizes such a transformation. Accordingly, the main mission of the University would be to serve the economy, specifically through the training of human resources, as well as the production of knowledge, for that purpose. Other functions would be cast into the background. In order for this institution to adjust to its new priorities, the author affirms that a new culture would have to impose itself on the University: a new way of considering accountability—so called “new accountability”—with financial accounting at its core; the dissemination of a new practice of highly ideological management (“new public management” or “new managerialism”); and a new way of utilizing human resources with the goal of maximizing efficiency. In short, an entrepreneurial outlook on the concept of “University”.

A few years later, the document The New Economy. Beyond the Hype (OECD, 2001) essentially anticipated the impact of the then new model of University on the prioritization of the various fields of knowledge. The success of this “New Economy”, where a noticeable rise in investment in information and communication technologies (ICT) was apparent, required individuals qualified not only to work with these technologies but also fit to answer the new organizational challenges brought about by them. Due to this, areas such as ICT and management began to become promoted more strongly, namely in higher education and research, and the connection between higher education and the job market strengthened.

An indirect discrimination of the humanities was thus induced, with real-world consequences. One of the symptoms relating to such a social phenomenon has been a progressively lower relative representation of graduates in humanities and, in some countries, also of the absolute representation, especially with regards to doctorate degrees. For instance, in the period between 2000 and 2012, while the number of humanities graduates rose by a factor of 1.4—and that of total graduates by a factor of 1.6 overall—those in the area of business administration increased by a factor of 1.8Footnote 4. For perspective, this accounts for virtually a fifth of total graduates. In other words, although academia within the humanities is growing, it is doing so at a disproportionately lower pace than when compared with other fields.

As Pierre Bourdieu had already outlined in Homo Academicvs (Bourdieu, 1984), alterations in the relative representation of students of certain areas, and thus of respective University staff, have an impact not only on power balances within the University, but also on its influence on society itself. The author saw these as morphological changes—a point of view that shapes the following considerations.

The impact of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities

With regard to the internal impact of shrinking resources within academic departments of the humanities, we can identify several clues as to how the University has generally been placing a lower importance on the humanitiesFootnote 5:

-

Cuts in the financing of research and teaching;

-

a lower share of the space and structure within the University, through the elimination of courses and even departments;

-

undervalued human resources (fewer job offers, falling wages, overloaded work schedules, aging staff, lack of opportunities for the young);

-

a decrease in library resources and the like;

-

the use of evaluation methods typical of scientific activity and which are unadjusted to the specificity of the humanities, indirectly resulting in pressure to change communication practices specific to these fields and weakening their social impact;

-

the extent to which some fields in the humanities are weakened, reaching dimensions so residual that they become at risk of disappearing.

These phenomena, even when not simultaneous, contribute to paving the way to further devaluation as they ultimately work together to make the humanities look progressively less attractive. In an academic context we are essentially confronted with a vicious cycle of devaluation. The next two sections deal with a series of reasons for why it becomes urgent to break such a cycle.

If on the one hand we are witnessing a shrinking of resources within academic departments of the humanities, on the other we can see a clear reduction in the relative representation of humanities graduates entering the job market. Without going too much into detail on the interdependence between these two phenomena, they stand as symptoms of a clear loss of influence of the humanities on society itself – perhaps the result of a growing incomprehension of their usefulness. Indeed, the field appears to be held hostage to a way of appreciation that is overly focused on the economy, established by those who govern and apparently accepted by most of those governed. Governors in particular tend to have a peculiar, restricted and limited way of evaluating, classifying and neglecting the humanities, even if opinions amongst themselves are not always in agreement. Through this lens, the field can be pretentiously seen as a luxury, as economically irrelevant, or even as useless - worse still, as an obstacle to access the job marketFootnote 6.

These dynamics make it even more difficult for academics in the humanities to convince others of the relevance of their area. Therefore, when competing with other areas for resources, the overall trend has been to deprioritise the humanities.

In the above-mentioned report titled Towards Knowledge Societies, UNESCO recognized that political choices tend sometimes to place a high importance on specific disciplines, namely ‘at the expense of the humanities’ (UNESCO, 2005, p. 90). These words are coated with a subtle yet sharp sense of loss. But what is in fact lost when the humanities see their presence in society diminished?

The benefits of studying the humanities

An analysis of several sources of information, such as surveys, studies and websites, has made it possible to understand the point of view of different social actors who believe there are advantages to graduating in the humanities (Costa, 2016). Students (Armitage et al., 2013), graduates (Lamb et al., 2012) and researchers (Levitt et al., 2010) in the humanities share their opinion on what the main advantages are, and their takes coincide with the way humanities courses are promoted on the websites of the universities that were taken into account in the analysisFootnote 7. As it would turn out, these advantages match the profile of the ideal employee as outlined by a group of employers as a condition to achieve success at their companies, according to a separate study that is unrelated to the humanities in particular (Hart Research Associates, 2013). In other words, even neoliberal standards and concerns are adequately addressed.

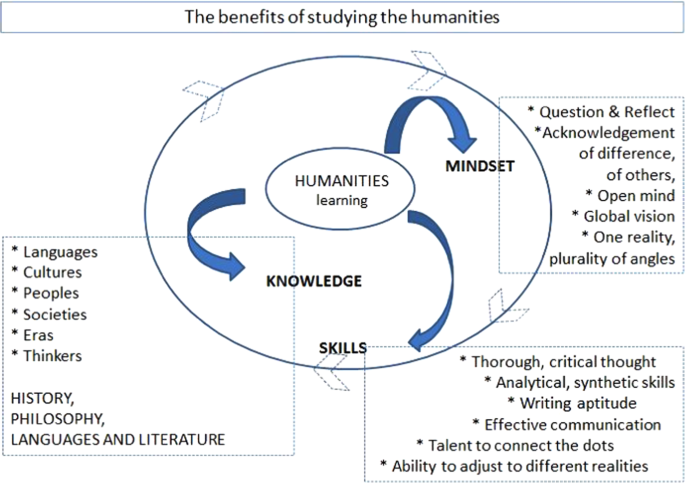

At its core, this acknowledgement of the value of the humanities can be looked at in three independent, mutually reinforcing levels: the comprehensive knowledge, skills and mindset that come with studying the field, and which are not easily outdated. These assets represent the genuine and specific character of studying these disciplines, and substantially differ from the priorities set by the political guidelines mentioned earlier. The following picture clarifies the scope of each of these levels (Fig. 1).

Benefits of studying the humanities. Source: adapted from Costa, 2017, with permission of the Portuguese Association of Professionals in Sociology of Organizations and Work–APSIOT. The figure is not covered by the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence

The attraction of studying the humanities lies precisely in that which one sets out to know and experiment with when one opts to study them. History, philosophy, languages and literature, to mention a few, are nuclear subjects that give us direct access to knowledge on that which is fundamentally and irreducibly human.

The challenge that this knowledge presents us with, and the effort of interpreting and attributing meaning to ourselves and that which surrounds us, are enhancers of the skills and mindset highlighted in the above graphic and their value is undeniable. Critical thought, acknowledgement of others, the ability to adjust to different realities and so forth are indispensable traits in any situation—in any institution, organization, government or company. It would thus follow that the humanities should be as explicitly and directly promoted by public policy as is specialized knowledge that directly serves firms and markets.

In spite of the value that can be recognized in studying the humanities, it stands that in the last few decades education in the field has been reduced to an almost insignificant dimension relative to other areas. It should be noted that demand in higher education is representative not just of the expectations of the students, or even of their educational and social backgrounds. It is also conditioned by the choices of a large group of social actors, interdependent amongst themselvesFootnote 8, such as decision makers – be it national or international, political or institutional –, employers and parents. But this depreciation has not been exclusive to higher education only. It has led to generalized deficits in knowledge, sensitivity and imagination, cognitive resources which are necessary to the acknowledgement of real problems within society and likewise to the development of possible solutions. The ability for citizens to possess and demonstrate a mindset of critical thinking has in this way been undermined.

One can thus argue that, at the very least from a social standpoint, much could be lost here. Martha Nussbaum warned in 2010 about the dangers this poses to democracy itself. The number of billionaires has nearly doubled as wealth has become even more concentrated in the last ten years since the financial crisis, worsening social inequalities (OXFAM, 2019). A society of consumption and uncontrolled, unregulated and acritical exploitation of natural resources is hindering sustainable development. Perhaps somewhat ironically, even the market economy registers some losses of its own in this scenario. The University of Oxford studied the career path of a group of their graduates in humanities, who had been students from 1960–1989, and subsequently produced a report that ‘shines a light on the breadth and variety of roles in society that they adopt, and the striking consistency with which they have had successful careers in sectors driving economic growth’ (Kreager, 2013, p. 1). This conclusion contradicts the vision, or perhaps the bias, according to which graduations within the humanities are considered useless and of no value, especially for the economy and the labour market in general. The TED Talk Why tech needs the humanitiesFootnote 9 (December 2017) addresses this issue in the light yet personal manner of someone who has experienced it first hand.

On the complementarity of the various knowledge fields within society

In contrast to the trend within the humanities, from 2000 to 2012 and as previously mentioned, graduates in the area of business administration grew both in numbers and in relevance. Georges Corm (2013) considers that a new wave of employees, trained in accordance with the neoliberal ideas, has emerged in the job market. In his opinion, this is noticeable for instance in the case of MBAs, which in general have a similar format in use in the best schools around the world. Engwall et al. (2010) had already come to the conclusion that these graduates have become the new elite, taking up the leadership positions within organizations, replacing graduates namely in law and in engineering.

According to Colin Crouch (2016), ‘financial expertise has become the privileged form of knowledge, trumping other kinds, because it is embedded in the operation of […] the institutions that ensure profit maximization […]. Under certain conditions this dominance of financial knowledge can become self-destructive, destroying other forms of knowledge on which its own future depends’ (ibid., p. 34). Indeed, ‘serious problems arise when one kind of knowledge systematically triumphs over others’ (ibid., p. 35), a sentiment the author illustrates by giving examples related to engineering and geology. It can be argued that such a large pool of graduates and post-graduates in business administration has severely disrupted the balance and the complementarity of wisdom in society.

The environmental disasters and social crises that have marked the last decade, and which we have all witnessed, mean that the priority which had been given to some fields of knowledge is a concern not just of the academic community, but that it should instead be seen as an issue for all of society. If we start discrediting certain kinds of knowledge, we might end up discrediting all which are not in accordance with the interests that prevail in society at any given point in time, interests which in turn might not necessarily have the common good as their priority. This would be akin to opening a Pandora’s box.

Where has this led us? For instance, few of us are unaware of the difficulties that scientific evidence faces today in order to be appreciated and accepted by people who are farthest from the world of science, and who will more easily trust populist discourses (Baron, 2016; Boyd, 2016; Gluckman, 2017; Horton and Brown, 2018). Current disinvestment in the teachings of philosophy, particularly in the young, pulls us away from the basic foundations of knowledge and science, ultimately furthering the establishment of a post-truth society.

Concluding remarks

The process of devaluation of the humanities fortunately has not been enough to nullify the voice and ongoing work of their community. The World Humanities Conference, mentioned at the very beginning of this text, is a sign of the vitality and pertinence that this field still holds. When we look at the topics discussed at this conference, they are undoubtedly of great relevance for the society of today: ‘Humanity and the environment’; ‘Cultural identities, cultural diversities and intercultural relations: a global multicultural humanity’; ‘Borders and migrations’; ‘Heritage’; ‘History, memory and politics’; ‘The humanities in a changing world. What changes the world and in the world? What changes the humanities and in the humanities?’; and ‘Rebuilding the humanities, rebuilding humanism’. Events like this conference allow for the hope that a new and virtuous cycle for the humanities could be on the upswing for the benefit of all of society. One which will be more permeable and welcoming to all knowledge and skills, valuing all of its fields in a fair and impartial manner. Ultimately, the hope is to have a society that is zealous and proactive in the protection of a rich diversity of knowledge from the establishment and dominance of political hierarchies.

Notes

Set of years for which OECD data are available in a usable way (verified in 23 May 2018 at OECD.Stat).

According to the ISCED 1997 (levels 5A and 6)—International Standard Classification of Education 1997 (first and second stages of tertiary education).

For this indicator, data for a subset of thirty OECD countries were used.

This systematization is based on the interpretation of a plurality of official statistics and reports on several countries (Costa, 2016).

Observations based on several publications, some of which are included in the bibliography (Benneworth and Jongbloed, 2010; Bod, 2011; Bok, 2007; Brinkley, 2009; Classen, 2012; Donoghue, 2010; European University Association, 2011; Fish, 2010; Gewirtz and Cribb, 2013; Gumport, 2000; Nussbaum, 2010; Weiland, 1992).

Harvard University (http://artsandhumanities.fas.harvard.edu), Stanford Humanities Center (http://shc.stanford.edu/why-do-humanities-matter), University of Chicago´s Master of Arts Program in the Humanities (http://maph.uchicago.edu/directors) and MIT School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences (http://shass.mit.edu/news/news-2014-power-of-humanities-arts-socialsciences-at-mit). Data last updated from these websites: October 2015.

This statement is highly influenced by the thought of Norbert Elias, namely his concept of configuration (Elias, 2015 [1970]).

References

Altbach PG, Reisberg L, Rumbley LE (2009) Trends in global higher education: tracking an academic revolution. A report prepared for the UNESCO 2009 World Conference on Higher Education. UNESCO, Paris

Armitage D et al. (2013) The teaching of the arts and humanities at Harvard College. Mapping the future. Harvard University, Cambridge

Baron N (2016) So you want to change the world? Nature 540:517–519

Benneworth P, Jongbloed BW (2010) Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorisation. Higher Educ 59(5):567–588

Bod R (2011) How the humanities changed the world: or why we should stop worrying and love the history of the humanities. Annuario 2011-2012–Unione Internazionale Degli Istituti Di Archeologia Storia E Storia dell’Arte in Roma 53:189–200

Bok D (2007, June 7) Remarks of President Derek Bok. Harvard Gazette. http://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2007/06/remarks-of-president-derek-bok/

Bourdieu P (1984) Homo academicvs. Minuit, Paris

Boyd IL (2016) Take the long view. Nature 540:520–521

Brinkley A (2009) The landscape of humanities research and funding. http://archive201406.humanitiesindicators.org/essays/brinkley.pdf

Classen A (2012) Humanities-to be or not to be, that is the question. Humanities 1:54–61

Corm G (2013) Le Nouveau Gouvernment du Monde. Idéologies, Structures, Contre-Pouvoirs. La Découverte, Paris

Costa RC (2016) A desvalorização das humanidades: universidade, transformações sociais e neoliberalismo. Doctoral Thesis: ISCTE-IUL, Lisboa, https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/12371/1/tese%20nova%20subcapa.pdf

Costa RC (2017) Novas políticas de ensino superior para a quarta Revolução Industrial. Um lugar para as Humanidades. In: XVII Encontro Nacional de SIOT. APSIOT: Lisboa. https://repositorio.iscte-iul.pt/bitstream/10071/16251/1/04_xvii_Ros%C3%A1rio_Couto_Costa.pdf

Crouch C (2016) The knowledge corrupters: hidden consequences of the financial takeover of public life. Polity Press, Cambridge

Donoghue F (2010, September 5) Can the Humanities Survive the 21st Century? The Chronicle of Higher Education. http://chronicle.com/article/Can-the-Humanities-Survive-the/124222/

Elias N (2015) Introdução à Sociologia. Edições70, Lisboa, [1970]

Engwall L, Kipping M, Usdiken B (2010) Public Science Systems, Higher Education, and the Trajectory of Academic Disciplines: Business Studies in the Unites States and Europe. In: Whitley R, Glässer J, Engwall L (eds) Reconfiguring Knowledge Production. Changing Authority Relationship in the Sciences and their Consequences for Intellectual Innovation. Oxford University, Oxford, p 325–353

European University Association (2011) Impact of the economic crisis on European Universities. EUA, Brussels

Fish S (2010, October 11) The crisis of the humanities officially arrives. The New York Times. http://www3.qcc.cuny.edu/WikiFiles/file/The%20Crisis%20of%20the%20Humanities%20Officially%20Arrives%20-%20NYTimes.com-1.pdf

Gewirtz S, Cribb A (2013) Representing 30 years of Higher Education Change: UK Universities and The Times Higher. J Educ Admin Hist 45(1):58–83

Gibbons M (1998) Higher education relevance in the 21st Century. World Bank, Washington, D.C

Gluckman P (2017) Scientific advice in a troubled world. The Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, Wellington

Gumport PJ (2000) Academic restructuring: organizational change and institutional imperatives. Higher Educ 39:67–91

Hart Research Associates (2013) It takes More than a Major. Employer priorities for college learning and student success. Association of American Colleges and Universities, Washington, D.C

Heywood A (2014) Global politics. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Horton P, Brown GW (2018) Integrating evidence, politics and society: a methodology for the science–policy interface. Pal Commun 4:42

Johnstone DB, Arora A, Experton W (1998) The financing and management of higher education. A status report on worldwide reforms. World Bank, Washington, DC

Kreager P (2013) Humanities graduates and the british economy. The hidden impact. University of Oxford, Oxford

Lamb H et al. (2012) Employability in the faculty of arts and social sciences. Final Report. CFE, Leicester

Levitt R et al. (2010) Assessing the impact of arts and humanities research at the University of Cambridge. Rand Corporation, Santa Monica, CA

Nussbaum MC (2010) Not for profit. Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University, Princeton

Peck J (2012) Neoliberalismo y crisis actual. Documentos y Aportes en Administración Pública y Gestión Estatal 12(19):7–27

OECD (2001) The new economy. Beyond the hype. Final Report on the OECD Growth Project. OECD, Paris

OXFAM (2019) Public good or private wealth? Oxfam GB, Oxford

UNESCO (2005) Towards knowledge societies. UNESCO, Paris

Weiland JS (1992) Humanities: introduction. In: Clark BR, Neave G (eds) The encyclopedia of higher education. Pergamon Press, Oxford, p 1981–1989

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa, R.C. The place of the humanities in today’s knowledge society. Palgrave Commun 5, 38 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0245-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0245-6