Abstract

The cornerstone of modern finance is the efficient market hypothesis. Under this hypothesis all information available about a financial asset is immediately incorporated into its price dynamics by fully rational investors. In contrast to this hypothesis many studies have pointed out behavioral biases in investors. Recently it has become possible to access databases that track the trading decisions of investors. Studies of such databases have shown that investors acting in a financial market are highly heterogeneous among them, and that heterogeneity is a common characteristic of many financial markets. The article describes an empirical study of the daily trading decisions of all Finnish investors investing Nokia stock over a time period of 15 years. The investigation is performed by adapting and using methods and tools in network science. By investigating daily trading decisions, and by constructing the time-evolution of statistically validated networks of investors, clusters of investors—and their time evolution— which are characterized by similar trading profiles are detected. These clusters are performing distinct trading decisions on time scales ranging from several months to twelve years. These empirical observations show the presence of an ecology of groups of investors characterized by different attributes and by various investment styles over many years. Some of the detected clusters present a persistent over-expression of specific investor categories. The study shows that the logarithm of the ratio of pairs of statistically validated trading decisions is different for different values of the market volatility. These findings suggest that an ecology of investors is present in financial markets and that groups of traders are always competing, adopting, using and eventually discarding new investment strategies. This adaptation process is observed over a multiplicity of time scales, and is compatible with several conclusions of behavioral finance and with the assumptions of the so-called adaptive market hypothesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The efficient market hypothesis (Fama, 1970; Fama, 1991) states that information about the present and future states of the world impacting the price of financial assets are immediately incorporated into their price dynamics. Within this hypothesis it is possible to describe the trading decisions of market participants in terms of those of a representative agent subsuming the diverse characteristics of traders. On the other hand, many empirical and theoretical studies have highlighted the presence of a high degree of heterogeneity in the nature and trading styles of investors. Some studies have pointed out specific trading profiles held by institutional and individual investors (Lakonishok and Maberly, 1990; Lakonishok et al. 1992; Nofsinger and Sias, 1999; Barber and Odean, 2007; Barber et al. 2008; Kirilenko et al. 2017).

Another conceptual framework assuming heterogeneity of traders is that of market microstructure. This research area of finance hypothesizes the presence of different types of traders, e.g., informed, non-informed and market makers in its models (Kyle, 1985; O’hara, 1995). This heterogeneity has been investigated in several market microstructure studies (Bouchaud et al. 2009). A number of researchers have characterized investors by using the stylized concepts of fundamentalists, i.e., investors considering the fundamentals of the company of the considered financial asset, and chartists or noise traders, i.e., investors focusing on idiosyncratic reasons and/or on historical patterns of return and other market indicators such as volume and volatility (Black, 1986; Kirman, 1993; Brock and Hommes, 1998; Lux and Marchesi, 1999).

Behavioral finance has pointed out specific traits of households investors (Shiller 2003; Thaler, 2005) characterizing their trading decisions. A large amount of empirical evidence shows that households present behavioral characteristics that cannot be straightforwardly explained in terms of financial theory (Campbell, 2006). An early piece of evidence of behavioral bias in households investors was the discovery of the so-called disposition effect, i.e., the observation that retail investors have a preferential tendency to sell stocks that keep going up in price and hold those that keep going down (Odean, 1998; Feng and Seasholes, 2005; Dorn et al. 2008). Another robust stylized observation concerns the degree of portfolio diversification (Grinblatt and Keloharju, 2000; Campbell, 2006; Calvet et al. 2007; Goetzmann and Kumar, 2008). In fact, households on average invest in portfolios with a number of stocks that is much less than the number of stocks in portfolios of other categories of investors. Empirical investigations also point out a limited level of financial competence and the so-called home bias (Grinblatt and Keloharju, 2001; Graham et al. 2009), i.e., the preference towards stocks of companies that are regionally closer to the residence of the investor. Other studies have also considered the ability of household investors to overcome their behavioral biases (Feng and Seasholes, 2005) and to learn (Seru et al. 2009) from their trading history. Other studies have considered the trading frequency of retail investors. Specifically, scholars have investigated whether retail investors are trading too much (Odean 1999; Gervais and Odean, 2001; Dorn and Huberman, 2005; Glaser and Weber, 2007; Graham et al. 2009).

The heterogeneity of investors supports the existence of a market ecology of different traders (Farmer and Lo, 1999; Farmer 2002). The term market ecology (Farmer, 2002; Challet et al. 2005; Bouchaud et al. 2018) was introduced in the finance literature (Farmer, 2002) for two main reasons. Firstly, as in biological sciences, it draws attention to the relationships of market participants amongst themselves and within the financial and economic environment, e.g., evaluation of endogenous market information and/or evaluation and processing of exogenous information arriving into the market. Secondly, an ecological setting considers “species” of investors and studies their trading decisions without necessarily performing a modeling of the reasons why certain categories of investors are present in the market (Farmer, 2002).

The existence of a market ecology of investors is compatible with some assumptions of behavioral finance. A market ecology also provides a framework for the adaptive markets hypothesis (AMH) (Lo, 2004). In the AMH financial markets are only marginally efficient and groups of traders are competing amongst themselves by inventing, using, adopting, and discarding investment strategies. This adaptation process usually presents multiple time scales.

The investigation of investors acting in financial markets has also been performed within interdisciplinary studies jointly using concepts of finance, computer science, statistical physics, and network science (Newman, 2010, Barabasi, 2016). For example, Morton de Lachapelle and Challet, 2010 studied the heterogeneity of the average portfolio value of individual investors trading through the largest online Swiss broker; Tumminello et al. (2012) detected clusters of investors characterized by a high degree of similarity in their trading decisions; Fei and Zhou (2013) studied the trading profile of packages traded by two broad categories of investors operating in the Chinese stock market; Challet and Morton de Lachapelle (2013) presented an analysis of investment fluxes of individual investors, companies, and asset managers that were clients of an online broker and detected robust evidence of the contrarian attitude of retail investors; Bohlin and Rosvall (2014) investigated the relationship between the similarity of portfolios and the similarity in trading decisions for Swedish investors; Lillo et al. (2015) studied how the presence of news about a given stock impacts the trading decisions of different categories of investors, and Musciotto et al. (2016) obtained clusters of investors characterized by analogous trading profiles by using two different statistical methodologies.

Most of the studies on empirical investigations of the trading decisions of individual investors have been performed by covering relatively limited periods of time. Here we study the long-term dynamics of trading decisions of groups of Finnish investors investing into the Nokia stock. Our study covers the 15 year time period from 1/1995 to 12/2009. During the investigated years, Nokia stock was one of the most capitalized and liquid stock traded on the Nordic Stock Exchange. The Nokia stock was also traded in several other stock exchanges around the world. Due to the details of the investigated database we are able to track and analyze trading decision of investors on a daily basis for a time period of 15 years (see the section of dataset and methodology for details). Investors are classified in six broad categories defined as financial corporations, households, governmental organizations, foreign organizations, non-financial corporations, and non-profit organizations on the basis of legal information.

In the present study, we adapt and use the methodology of statistically validated networks (Tumminello et al. 2011a) on a yearly time base (i.e., by using approximately 250 trading records per year). Statistically validated networks have been introduced in network science to highlight over-expressed relationships observed between pair of agents of a complex system when repeated interactions are performed among them. A specific property of this approach is that the methodology is designed to minimize false positives related to heterogeneity of the actors or to familywise error. In the present study, agents are Nokia investors and repeated interactions are buying, selling or buying-selling trading decisions of Nokia shares.

With this approach, for each calendar year we detect groups of heterogeneous investors that are presenting similar timing and profile of trading decisions and we investigate their time evolution over the years. We discover that the market of Nokia shares presents an ecology of groups of investors that are active over the years and are characterized by different attributes. The time scales of the profile of their trading decisions are ranging from a few months to twelve years. The different groups of investors evolving over time often present an over-expression of investors belonging to a specific category. Our empirical results show the presence of an ecology of investors characterized by dynamics with time scales ranging from several months to a decade.

The paper is organized as follows. In section Dataset and methodology we describe the database and our methodology of statistically validated networks. We discuss how the methodology is based on concepts and tools in network science. In section Results, we present the obtained results, discuss the statistical power of the test, and visualize the obtained results. The Dynamics of statistically validated networks of investors is investigated in the next section. The section on Long term ecology of clusters investigates the time evolution of clusters and characterizes chains of clusters in terms of four attributes of investors. The role of market volatility is also discussed in this section. The last section presents conclusions.

Dataset and methodology

Dataset

In this paper we investigate the daily trading decisions of investors (corporations, organizations, and individuals) trading the Nokia stock during the time period from January 1995 to December 2009. Our data source is the financial asset ownership database collected by Euroclear Finland (previously Nordic Central Securities Depository Finland). This database is obtained from the central register of shareholdings for Finnish financial assets recorded at the Finnish Central Securities Depository. The register records the shareholdings (both institutional and retail) of all Finnish investors and of those foreign investors exercising their vote right. The database is updated on a daily basis. Recorded transactions cover the Nordic Stock Exchange and worldwide stock exchanges where Nokia stock was traded in the considered period of time.

In our study, each investor is identified by a unique legal entity. Euroclear Finland classifies investors into six broad categories; they are: non-financial corporations, financial and insurance corporations, general governmental organizations, non-profit institutions, households, and foreign organizations. The starting date of the database is January 1st, 1995. The database was updated from the starting date until 2009 by considering each market transaction done by investors. At the end of 2009 technical changes in recording the date of transactions and aggregation of market transactions of the same investors limit the usability of the data. Due to this technical change, even though the data is available up to the current date, we study the period 1995–2009.

Several studies have used this database to investigate characteristics of the investment decisions of distinct categories of investors. A series of studies has been performed by Grinblatt and Keloharju (Grinblatt and Keloharju, 2000; Grinblatt and Keloharju, 2009) primarily focusing on the trading style of individual and institutional investors, and on behavioral aspects in investors of the households category. Other studies have considered the synchronicity of trading decisions of investors (Tumminello et al. 2012; Musciotto et al. 2016), and the reaction of different categories of investors to endogenous and exogenous flow of market information (Lillo et al. 2015).

Legal considerations impact the way the database is designed and information is stored. For example, information about Finnish domestic investors (or foreign investors asking to exercise their vote right) and foreign investors can be stored in a quite different way. In fact, foreign investors can choose to use nominee registration. In this last case, the provider of the investor’s ownership, for example a bank, can aggregate all transactions from all of its accounts, and a single nominee register coded identity contains the holdings of several foreign investors. Footnote 1

One key aspect of the trading activity of investors is heterogeneity. For example, there are investors which are acting only a few times during the considered time period and investors trading continuously. A summary statistics about the number of investors trading the Nokia stock over the investigated years is given in Table I and in Table II of SI. We are performing our analysis yearly. To quantify similarity in the trading decisions we require that an investor has performed a minimum number of trading decisions in each analyzed calendar year. For this reason, we select a set of investors called “active” investors; they are those investors that have done more than five transactions in a given calendar year. The summary statistics of this subset of investors is given in Table II of SI. A comparison between Table I and Table II of SI shows that the number of active investors is a rather limited fraction of the set of investors. On average active investors are approximately only 12.0% of the total number of investors. However this percentage primarily reflects the percentage of active households (10.4%) which is the most populated category of investors. When we consider the average percentage of active investors for other categories we obtain 57.3% for financial corporations, 55.6% for governmental organization, 23.8% for non-financial corporations, 15.2% for non-profit institutions, and 13.4% for foreign organizations. In other words corporations, institutions and organizations are on average more active than households and among the institutions and organizations, financial corporations and governmental organizations are the most active.

Methodology

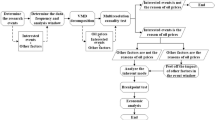

In this paper, we analyze the synchronous trading decisions of investors by using concepts and tools of complex networks (Newman, 2010; Barabasi, 2016). In our approach, for each calendar year, we define a bipartite network where one set of the nodes are investors and the other set of nodes are three types of trading decisions for each trading day. As frequently done in network science (Newman, 2010; Barabasi, 2016) from the bipartite network one obtains a projected network with nodes of just one type. Here we are considering the projected network of investors having performed the same trading decision of buying, selling, and buying and selling (see below for a quantitative definition) in at least one trading day. For such a liquid stock as Nokia, the projected network is rather dense. Many active investors are making the same trading decision in at least one day. These networks are therefore not especially informative regarding the high similarity of trading decision of groups of investors connected in the projected networks. To highlight pairs of investors that are characterized by a number of co-occurences of trading decisions that cannot be explained in terms of a random null hypothesis, we use the method of statistically validated networks Tumminello et al. (2011a). With this methodology, introduced in (Tumminello et al. 2012) and applied to Nokia investors in Musciotto et al. (2016), it is in fact possible to select those pairs of investors performing similar trading choices within a highly controlled statistical procedure that is robust with respect to the heterogeneity of the system. For the sake of completeness, we briefly sketch the statistical procedure below.

In statistics, a categorical variable can take a limited number of values describing a qualitative property. Specifically, we use a categorical variable describing the daily trading decisions of an investor. Our categorical variable is defined as follows: let us call Vs(i,t) the volume sold and Vb(i,t) the volume purchased of Nokia stock by the investor i at day t. We convert these quantities into a categorical variable with 3 possible states: investor primarily buying b, investor primarily selling s, and investor buying and selling bs during the trading day. The categorical variable is computed starting from the real quantity

When the condition r(i,t)>θ is verified, we consider investor i at day t in state b as primarily buying. A primarily selling state s is assigned when r(i,t)<−θ, whereas a buying and selling state bs is assigned when −θ /le r(i,t) /le θ with Vb(i,t)>0 and Vs(i,t)>0. In the present study, the categorical variable is obtained by setting θ = 0.01 as threshold value.

Statistically validated networks of investors

For each calendar year, we obtain a statistically validated network by performing the following procedure: For each pair i and j of active investors we estimate the overlap of their time periods of trading; this overlap NT is the number of days that are common between the two time intervals delimited by the first and last transaction performed by each investor during the considered calendar year. We call NA the number of days when investor i is in the state A and NB the number of days when investor j is in the state B. NA,B is the number of days with the simultaneous co-occurrence of state A for investor i and state B for investor J. Under a null hypothesis assuming random co-occurrence, the probability of observing X simultaneous co-occurrences of states A and B is given by the hypergeometric distribution H(X|NT,NA,NB) (Tumminello et al. 2011a). By using the probability of X co-occurrences, one can obtain a p-value.

For each pair of states A and B and for each pair of investors i and j, the p-value of observing NA,B co-occurrences or more is

We are considering three different trading states labeled as b (buying), s (selling), and bs (buying and selling). By investigating three trading states, we have nine combinations of co-occurrences of trading states involving each pair of investors i and j. For each calendar year, we are therefore performing a very large number of statistical tests and so to avoid false positives we need to take into account a multiple hypothesis test correction (Miller, 1981). In statistics, the most used procedures for the control of the familywise error rate are the Bonferroni correction and the control of the False Discovery Rate (FDR). The Bonferroni correction uses the most general assumptions. It minimizes the number of false positives but does not provide sufficient statistical accuracy in several cases. This is due to the fact that it usually allows a large number of false negatives. The FDR correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) reduces the number of false negatives without significantly increasing the number of false positives.

The Bonferroni correction is obtained by redefining the statistical threshold. In our study we use as the statistical threshold of a single statistical test the customary value of α = 0.01. For each year t we use as the Bonferroni statistical threshold the value αb = 0.01/Nt, where Nt is the number of pairs of active investors trading Nokia with at least one simultaneous trading day of activity. The control of the FDR is obtained with the following procedure: we first rank in increasing order all p-values obtained by considering all the l performed tests where l = 9Nt(Nt−1). This gives us the ranked sequence P1<P2<…<Pl. We then select the tests rejecting the null hypothesis by selecting the largest lmax such that \(p_{\ell _{max}} < \ell _{max}\,\alpha _b\). In this paper we use the control of the FDR as multiple hypothesis test correction.

Results

Households are the largest group of active investors and therefore an unconditional investigation is essentially reflecting their behavior. To discriminate among different categories of investors, in Fig. 1 we show the number of investors, the number of active investors, and the number of FDR investors (i.e., the number of investors observed in the statistically validated networks) as a function of calendar year for each of the six categories of the database. Figure 1 shows that households are primarily determining the unconditional statistics of the number of investors present in statistically validated networks (see the close analogy of the households panel of Fig. 1 with Fig. SI1 of SI), non-financial corporations show an overall profile analogous to the one observed for households whereas the remaining categories show patterns that are only roughly similar to the ones of households and non-financial corporations.

Number of investors (blue circles), number of active investors (green triangles down), and number of investors included in the FDR network (red triangles up) as a function of the calendar year. Each panel refers to a category of investors. In the top row we have households, financial institutions, and governmental organizations (from left to right), whereas in the bottom row we have foreign organizations, non-profit organizations, and non-financial corporations (from left to right)

Our investigation covers 15 years and we obtain a statistically validated network of active investors for each calendar year. In network science, the internal structure of networks is customarily investigated by detecting regions of the network where the nodes (in our case investors) are strongly interconnected with one another. An unsupervised detection of these regions is done by performing the so-called community detection procedures. The name originates from the fact that these techniques were originally introduced for the study of social networks. To highlight clusters of investors characterized by analogous trading decisions we apply the widely used Infomap community detection algorithm (Rosvall and Bergstrom, 2007). We consider each statistically validated network as a weighted network, i.e., we assign a weight to each link. This is done by defining the weight of each link connecting investors i and j as the number of statistically validated co-occurrences between them of the nine possible pairs of trading states. The majority of links have weights equal to one but links with weight equal to two are also observed.

In Table 1 we report summary statistics of the clusters of investors detected in the FDR networks with the community detection algorithm. The number of clusters and their size (in number of investors) is varying over time. The size of the clusters of investors observed is ranging from the minimum value of 2 to the maximal value of 425 (observed in 2005). Clusters of size larger than 100 investors are observed during the period from 2002 to 2005 and in 2008. Table II of the SI shows that the number of active investors is varying by more than one order of magnitude. In fact it is ranging from 764 in 1995 to 9651 in 2002. The statistical test used to obtain statistically validated networks has a power that is depending on the number of nodes (i.e., investors). In the next subsection we investigate whether the power of the test affects our results.

Power of the test

The first evidence that results of statistically validated networks are not affected by the power of the test can be concluded by analyzing the ratio of validated links to the total links observed for the different calendar years. This ratio is shown in Fig. 2 as red points. It is worth noting that although the year with the highest number of observed links is 2002 (see Table II of SI) and the power of the test is expected to be maximum for this year, the highest value of the ratio is observed in 2005. In order to assess the role of the power of the test in a rigorous way, we have designed the following numerical experiment. For each year, we have drawn ten random samples of fixed size from the pool of all the links that are present in the projected network of investors. When drawing the samples we have maintained the proportion of links among investors of the different categories as observed in the original set. For each random sample, we have obtained the corresponding statistically validated network. Figure 2 plots the ratio of validated links to total links both for the randomly selected samples (blue points) and for the whole system (red points). The random samples used in our numerical experiment contain all 1,000,000 links and therefore the test has the same power. The figure shows that the power of the test does not affect the estimation of the ratio of validated links to total links when we consider samples with a number of links equal to or larger than 1,000,000 and we use the FDR correction. This numerical experiment demonstrates that the dynamics of the size of statistically validated networks observed at different years are genuine dynamics of the financial market and of investors’ activity and it is not an artefact of the power of the test used.

Ratio of validated links as a function of the year. The samples investigated for the test contain 1,000,000 links each. Ten different realizations are used to estimate the average rate <r> of different random selections of links with the same size. The vertical blue bar gives the interval (<r>−σ,<r>+σ), where σ is the standard deviation of the ratio computed in 10 different realizations

Quantifying and visualizing the similarity of trading decisions of clusters

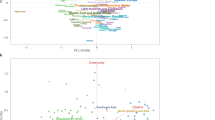

With our approach, for each calendar year we detect clusters whose investors are characterized by a high degree of similarity in their trading decisions. To quantify the similarity of collective trading decisions of different clusters we devise the following procedure. For each cluster we compute a vector where each record counts the number of investors of the cluster that are in state b, s, or bs each trading day of the calendar year. Such a vector has approximately 750 records (the exact number depends on the exact number of trading days of the considered year). The similarity between each pair of clusters is evaluated by estimating the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between the vectors of trading decisions of the two clusters. A simple and efficient way to highlight the main similarities present between the investment activity of different clusters is through the minimum spanning tree (MST) associated with the correlation coefficient matrix of all clusters of a given calendar year (Mantegna, 1999). In Fig. 3 we show the MST of investors’ clusters for 2005. Figure 3 is representative of the MSTs observed in different years. In the figure the first number of the cluster label is a numeric label and the second number are the last two digits of the calendar year. For example the cluster 0_05 is the cluster number 0 of 2005. It is worth noting that some clusters, for example clusters 0_05, 1_05, and 3_05, are located in distinct branches of the MST highlighting potential dissimilarity among them.

Minimum spanning tree of the similarity matrix associated with the trading activity of clusters for year 2005. Each cluster is labeled by a number. Symbols in colors indicate the over-expression of one or more category of investors. Colors refer to the different categories as follows: non-financial corporations (green), financial and insurance corporations (red), general governmental organizations (gray), non-profit organizations (yellow), households (cyan), and foreign organizations (brown). The size of each node is proportional to the logarithm of the number of investors that are in the cluster

In our analysis, we also investigate whether each cluster presents an over-expression of the number of investors of a given category. The statistical test used to perform this kind of analysis is described in (Tumminello et al., 2011b). It should be noted that the result of this statistical test is providing the over-expression of the number of investors belonging to a specific category with respect to a null hypothesis assuming a heterogeneous number of investors in the different categories. When the over-expression is detected, we label the symbol of the cluster with a given color. For example the cluster 0_05 has an over-expression of households (cyan color) and of non-financial corporations (green color). Other clusters showing over-expression of some category of investors are clusters 1_05 (households over-expression), 3_05 (households over-expression), 6_05 (governmental over-expression, label in gray color), and 27_05 (financial over-expression, label in red color).

In Fig. 4 we provide a direct visualization of a few types of synchronicity of trading decisions of investors belonging to six representative clusters of 2005. In the horizontal axis we have distinct investors of the cluster whereas we have the trading day in the vertical axis. In the figure we label a buying day of an investor with a green spot, a red spot indicates a selling day, a white spot is used when the investor performs a buy-selling activity during the day, and a black spot indicates the absence of trading. Visual inspection of Fig. 4 suggests that the trading strategy of the six selected clusters is rather different under many aspects. The most evident ones concern the frequency of trading, the number of investors, and the specific sequence of buy, sell, and buy-sell trading decisions. For example, clusters 0_05 and 2_05 are characterized by a low frequency of trading. On the contrary, 27_05 and 1_05 are characterized by a high frequency of trading whereas 3_05 and 6_05 show an intermediate level. Similarity of the profile is often related to synchronous buying (green lines) and selling (red lines) trading decisions. However synchronous buying and selling decisions also have a prominent role for some clusters. Examples are clusters 27_05 and 1_05.

Trading states of Nokia investors for clusters 0_05 (top left panel), 2_05 (top right panel), 3_05 (middle left panel), 6_05 (middle right panel), 27_05 (bottom left panel), and 1_05 (bottom right panel). We plot investors in the horizontal axis and time in vertical axis (in trading days from top to bottom). A green spot indicates a primarily buying day, a red spot a primarily selling day and a white spot a buy-selling day. When no trading is performed we use a black spot

Dynamics of statistically validated networks of investors

The investors’ composition and investment profile of clusters are changing year after year. To relate investors of a cluster in a given year to investors of clusters in the successive year, we use a statistical test of the over-representation of the number of investors that are present in both clusters against a null hypothesis that takes into account the heterogeneity of the size of the clusters. We perform the test as indicated in (Marotta et al. 2015). The test is performed on all clusters with more than five investors. For the sake of completeness, hereafter we briefly describe the procedure of the statistical test about time dynamics of clusters.

Statistically validated time dynamics of clusters

We label each calendar year with the integer k and Nk is the number of clusters \(C_i^k\), i = 1,..,Nk observed at year k. With this notation there are Nk+1 clusters \(C_j^{k + 1}\), j = 1,..,Nk+1 at year k+1. We call \(n_i^k\) the number of investors of cluster \(C_i^k\). Similarly \(n_j^{k + 1}\) is the number of investors of cluster \(C_j^{k + 1}\). We call \(n_{ij}^{k,k + 1}\) the number of investors which are both in cluster \(C_i^k\) and in cluster \(C_j^{k + 1}\). Nk,k+1 is the number of distinct investors that are trading in at least one of years k and k+1. Under the null hypothesis of random partitioning of investors, the hypergeometric distribution \(H\left( {n_{ij}^{k,k + 1}|N^{k,k + 1},n_i^k,n_j^{k + 1}} \right)\) gives the probability that \(n_{ij}^{k,k + 1}\) co-occurrences of investors are observed in clusters \(C_i^k\) and in cluster \(C_j^{k + 1}\). By using this probability, one can obtain a p-value associated with the observation of \(n_{ij}^{k,k + 1}\) or more co-occurrences of investors. The p-value is

This methodology (Marotta et al. 2015) allows us to select clusters in year k+1 that present an over-expressed number of investors that were also present in clusters at year k. When the p-value is below a statistical threshold we connect with a directed link the clusters selected by the statistical test. Also in this case we are performing a multiple comparison procedure and therefore a multiple hypothesis test correction is necessary. We perform these tests for all pairs of consecutive years from 1995 to 2009 by using the control of the FDR procedure with a threshold given by

Several clusters’ pairs present over-expression of the presence of same investors in a cluster m at year k and in a cluster n at year k+1. When this is the case we connect with a direct link cluster m_k with cluster n_k+1. Roughly twenty percent of clusters with more than 5 investors are connected with at least one cluster of next calendar year. We address these clusters whose time evolution is validated by a statistical test as chained clusters. Several of these chained clusters have a large number of investors. In fact chained clusters comprise approximately from 20 to 50 percent of the number of investors that are present in clusters with more than 5 investors. The details about the number of clusters and investors for both chained and all clusters are given in Table 1.

In Fig. 5 we show the time evolution of these clusters. The time duration of the observed cluster evolutions range from a minimum of 2 years to a maximum of 12 years (see the cluster evolution starting from 7_98 and ending at 34_09). We also observe the coalescence of several clusters (see, for example, the coalescence of clusters 2_02, 3_02, 6_02, 22_02 and 34_02 into the cluster 0_03 in the middle of the figure), and the splitting of a cluster in two clusters (e.g., the splitting of 1_05 into 1_06 and 5_06). When several clusters coalesce, they are characterized by a similarity between pairs of them that is typically higher than the similarity with other clusters. This is reflected in the corresponding MST where these clusters are located in a closely connected subnetwork of the tree. In Fig. SI2 of SI we show the MST for year 2002 where the above cited clusters are closely located.

Time evolution of the clusters detected in the FDR networks. Clusters are represented by a square labeled with a numerical index and the year. A link is set between two clusters when the overlap between the number of investors present in a cluster at year k with the number of investors present at year k+1 is over-expressed with respect to a null hypothesis of random partitioning of investors maintaining the heterogeneity of cluster size. Chains of cluster evolution lasting several years (up to 12 years) are observed. Splitting and merging of clusters are also observed. Colored clusters are clusters characterized by an over-expression of one or more categories of investors

For several chains of clusters, the dynamics of the chains present regularities with respect to the type of investors over-expressed in the clusters. In Fig. 5 we highlight those clusters that present an over-expression of the number of investors of a given category (or categories) by labeling the cluster with the corresponding color (or colors). We see that several chains of clusters show a persistent over-expression of specific categories of investors. The most prominent example is the cluster evolution starting from 7_98 and ending at 34_09. In all clusters of the chain we observe over-expression of governmental organizations (clusters labeled with gray) with the additional over-expression of non-profit institutions (clusters labeled with yellow color) in some years. We also observe chains of clusters characterized by over-expression of households (see, for example, the chain from 11_02 and 61_02 to 2_07 and 3_07 and the chain from 0_02 to 5_06 and 1_06), households and non-financial corporations (see the chain from 13_00 to 0_05), financial corporations (starting from 22_03 and ending at 42_05 and from 46_04 to 27_05), non-profit institutions (see the chain from 13_07 to 10_09), or some combinations of the different categories.

The results summarized in Fig. 5 show that some clusters of investors use trading strategies coherently evolving over time on time scales up to several years. Moreover, some of these chains are characterized by over-expression of one or two categories of investors. In the next section, we analyze in detail some of these chains of clusters that are simultaneously present in the market. Our analysis shows that their trading decisions are markedly different from one another, confirming the existence of groups of investors simultaneously acting in the market with different approaches and strategies for long periods of time.

Long-term ecology of clusters

We analyze 4 different attributes that are chosen to characterize different aspects of investors and of their chosen trading strategies. The attributes we consider are: (i) the average pairwise distance d(i,j) between vectors of individual trading decisions of investors belonging to a cluster or to a group of clusters. Footnote 2 (ii) the average value of the ratio of number of trading days coinciding with earning announcement days divided by the total number of trading days, (iii) the average value of the number of stocks each investor of the cluster (or group of clusters) is investing in, and (iv) the average trading frequency of investors of the cluster (or group of clusters). The trading frequency of an investor is the ratio of the number of trading days he or she performed in the considered year divided by the total number of trading days of that year. Therefore, a trading frequency equal to one indicates trading activity of an investor that performed all trading days of the year. For each calendar year, these attributes are computed for each cluster (when the chain is involving just a single cluster per year) or group of clusters (when many clusters are part of a chain in a year, see for example clusters 8_01, 10_01 of the chain from 7_98 to 34_09).

The average distance gives us information about the degree of dissimilarity observed between the trading decisions of each pair of investors in a cluster. The average value of the ratio of earning announcement trading days provides information concerning the relevance of these special days in the trading decisions. A high value of this attribute highlights attention to fundamental news and/or timing of trading decisions associated with market trading days typically characterized by over-reaction of the market. We consider the average number of stocks owned by investors as a proxy of their knowledge about basic financial concepts such as investment diversification. The average trading frequency tells us information about the time horizon of investors during the year. In Table 2 we report the 15-year average of the yearly average value of the four attributes for each category of investors. The Table shows that the average number of stocks in the portfolio of an investor is quite different for the different categories whereas the average distance between pairs of trading and the average of the ratio of earning announcement trading days is quite similar for all categories. The average frequency of trading is also quite similar for all categories of investors with the exception of financial corporations that are showing an average frequency of trading an order of magnitude higher than the other categories.

In Fig. 6 we show scatter plots of the 6 pairs of four attributes over the chain’s time-span. For each calendar year, besides the average, we also present information about the dispersion of the observed value by showing two segments indicating the interval of the attribute’s value from the first decile to the last one. All points and segments are provided in gray with the exception of tree groups of information referring to three specific cluster chains that are provided with crosses in color. The six panels of the figure show that the chain from 7_98 to 34_09 (red crosses), which is characterized by over-expression of investors belonging to governmental and non-profit institutions, presents attention to diversification (high value of the average number of stocks), low average frequency of trading (with two years of exception when an intermediate frequency of trading was chosen), moderate trading involvement during days of quarterly earnings, and relatively high similarity among investment profiles of investors. It is worth noting that points associated with this chain of clusters are quite distinct from the other two chains selected by us for illustrative purposes.

Scatter plot of four attributes characterizing a cluster or a group of clusters for each year. Each segment covers the values from the first decile to the last one. Crosses shown in color refer to the cluster chains from 7_98 to 34_09 (red crosses), from 13_00 to 0_05 (yellow crosses), and from 0_02 to 1_06 and 5_06 (green crosses)

Let us now consider the chain of clusters from 13_00 to 0_05 (yellow crosses). This chain is characterized by over-expression of households and non-financial corporations. Investors of this chain of clusters pay less attention than the previous ones to diversification. In fact they on average invest in portfolios with a number of stocks of the order of 15. Trading decisions are characterized by a low average frequency of trading and high involvement during days of quarterly earnings. The trading decisions present a high level of synchronicity as testified by the relatively low average distance between trading decisions of investors. The third chain describes the time evolution of clusters from 0_02 to 1_06 and 5_06 (green crosses). This chain is also characterized by over-expression of households. However, in spite of this common over-expression the time evolution of the chain of clusters is characterized by attributes that are quite different from the ones of the previous chain. Specifically, investors of this chain present moderate attention to diversification, relatively high average frequency of trading, low trading involvement during days of quarterly earnings, and a high average distance between trading decisions of investors (i.e., the trading decisions are rather heterogeneous in this case).

Our analysis therefore shows the presence of clusters of investors characterized by trading profiles that are different from one another, and that are observed in the market on time scales of many years or even decades.

The last investigation concerns the logarithm of the ratio of the number of validated links divided by the total number of links of the projected network of investors. We empirically observe a relationship between the logarithm of the ratio of validated links and the average daily volatility of Nokia’s stock computed each calendar year (see Fig. 7). Figure 7 shows that the two quantities are anti-correlated. In fact the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between them is −0.59. The presence of a pronounced empirical anti-correlation is not implying causation. However, this empirical correlation is consistent with a theoretical prediction obtained by Farmer, 2002 showing that the presence of a number of distinct trading strategies increases the volatility of the traded financial asset. In our empirical observation large clusters, i.e., a reduced number of similar strategies, are observed when the market is characterized by low values of volatility. In fact, years characterized by low market volatility are associated with high values of the logarithmic ratio and viceversa. Figure 7 also shows a rather peculiar pattern of the scatter plot. We observe that years (i) 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, and 2008 and (ii) 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2006, 2007, and 2009 are characterized by a quite different relationship. It is tempting to note that all the years of the onset of the dot-com financial bubble are in the second group but in the same group there are also years 2006, 2007, and 2009. Currently, we do not have an explanation for this pattern of the scatter plot.

Conclusions

Our study shows that it is possible to use methods originally introduced in network science to detect clusters of investors characterized by similar trading decisions of a financial asset. A key aspect for the success of the methodology used is its effectiveness in the statistical validation of large sets of heterogeneous investors. In fact, an empirically observed common trait of financial markets is the heterogeneity of the investors acting in the market. The size, composition, and time dynamics of these clusters of investors presents a large variability in terms of attributes of the investors. We have empirically verified that investors are heterogeneous with respect to their type of legal entity, frequency of trading, attention to earning announcements, type of portfolio owned, and pattern of trading decisions. It is worth noting that, with our approach, we are reaching the limit of analyzing and classifying trading decisions at the micro level of each single financial agent acting in the market.

With our approach, we show that the detected heterogeneity of clusters evolves with a temporal dynamics with time scales ranging from several months to several years. The presence of such long time scales provides empirical evidence about the presence of a market ecology of investors. These time scales are many orders of magnitude larger than the time scales of the price dynamics of the financial asset. Inside the market, the aggregation process of the information is therefore performed by heterogeneous clusters of investors that are maintaining their identity and style of trading on time scales covering up to many years.

Our results show that market volatility and the amount of similar synchronous trading decisions of investors are significantly anti-correlated. Some theoretical models (Farmer, 2002) predict that trading heterogeneity increases market volatility. Our empirical observation is consistent with these theoretical findings although the detection of anti-correlation cannot be interpreted as an evidence of causality. Unfortunately, estimating causality (even at the level of Granger, 1969 causality) is much more difficult than estimating correlation between two empirically detected variables and the present state of the art of our methodology does not allow us to detect causality. We therefore cannot conclude from empirical data whether trading heterogeneity increases volatility or rather higher values of market volatility increases the heterogeneity of trading decisions.

We believe that our empirical observation of the existence of a long-term market ecology of investors challenges the basic setting of the efficient market hypothesis. Our empirical results are better interpreted in terms of the hypothesis that heterogeneous investors are ubiquitously present in a financial market. These heterogeneous groups of traders can be characterized by different needs and attributes and are continuously adopting, and discarding new trading strategies at different time scales. The large body of literature of behavioral finance shows that this process of innovation and evaluation of trading decisions is often done in the presence of behavioral biases or constraints associated with the specific nature of investors. For example household investors are taking trading decisions that can be markedly different from the ones taken by financial corporations or governmental organizations as shown by studies about the disposition effect or about the learning attitude of investors. The presence of different types of investors, and of different clusters of investors all acting in the financial market with distinct and slowly evolving types of trading decisions is more consistent with a description of market activity done in terms of a market ecology (Farmer and Lo, 1999; Farmer, 2002) where investors are subjected to an adaptation process controlled by the success of their trading decisions. In other words, our results empirically support the description of a financial market in terms of the adaptive market hypothesis (Lo, 2004).

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during the current study is not publicly available and cannot be distributed by the authors because it is a proprietary database of Euroclear Finland. The database can be accessed for research purposes under confidentiality agreement by asking permission to Euroclear Finland.

Notes

To discriminate between the in-house trading activity of a financial corporation from its trading activity as nominee register we split the trading activity of a financial corporation into two distinct IDs. The first is recording its trading activity as an investor and the second one records the trades done for nominee registered (NR) investors.

The distance between investor i and j is measured first as a Jaccard similarity ρJ(i, j) and then transformed into a distance by using \(d\left( {i,j} \right) = \sqrt {2\left( {1 - \rho _J\left( {i,j} \right)} \right)}\). Specifically, we estimate the Jaccard similarity between the binary activity vectors of investors i and j. A binary activity vector is obtained for each investor by recording the presence (state 1) or absence (state 0) of buying, selling, or buy selling activity for each trading day of the year

References

Barber BM, Odean T (2007) All that glitters: The effect of attention and news on the buying behavior of individual and institutional investors. Rev Fin Stud 21:785–818

Barber BM, Lee Y, Liu Y, Odean T (2008) Just how much do individual investors lose by trading? Rev Fin Stud 22:609–632

Barabasi AL (2016) Network science. Cambridge university press, Cambridge, UK

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc B 57:289–300

Black F (1986) Noise. J Financ 41:528–543

Bohlin L, Rosvall M (2014) Stock portfolio structure of individual investors infers future trading behavior. PloS One 9(7):e103006

Bouchaud J-P, Farmer JD, Fabrizio L (2008) 'How Markets Slowly Digest Changes in Supply and Demand.' In Handbook of Financial Markets: Dynamics and Evolution, (eds) Thorsten Hens and Klaus Schenk-Hoppe. Elsevier: Academic Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA, 57–156

Bouchaud JP, Bonart J, Donier J, Gould M (2018) Trades, quotes and prices: financial markets under the microscope. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Brock WA, Hommes CH (1998) Heterogeneous beliefs and routes to chaos in a simple asset pricing model. J Econ Dyn Control 22:1235–1274

Calvet LE, Campbell JY, Sodini P (2007) Down or out: Assessing the welfare costs of household investment mistakes. J Political Econ 115:707–747

Campbell JY (2006) Household finance. J Financ 61:1553–1604

Challet D, Marsili M, Zhang YC (2005) Minority games: interacting agents in financial markets. Oxford university press, Oxford, UK

Challet D, Morton de Lachapelle D (2013) A Robust Measure of Investor Contrarian Behaviour In Econophysics of systemic risk and network dynamics, (eds) Abergel F, Chakrabarti BK, Chakraborti A, Ghosh A. Springer-Verlag, Italia, pp 105–118

Dorn D, Huberman G (2005) Talk and action: what individual investors say and what they do. Rev Financ 9:437–481

Dorn D, Huberman G, Sengmueller P (2008) Correlated trading and returns. J Financ 63:885–920

Fama EF (1970) Efficient capital markets: a review of theory and empirical work. J Financ 25:383–417

Fama EF (1991) Efficient capital markets: II. J Financ 46:1575–1617

Farmer JD (2002) Market force, ecology and evolution. Ind Corp Change 11(5):895–953

Farmer JD, Lo AW (1999) Frontiers of finance: evolution and efficient markets. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96(18):9991–9992

Fei R, Zhou WX (2013) Analysis of trade packages in the Chinese stock market. Quant Financ 13(7):1071–1089

Feng L, Seasholes MS (2005) Do investor sophistication and trading experience eliminate behavioral biases in financial markets? Rev Financ 9:305–351

Gervais S, Odean T (2001) Learning to be overconfident. Rev Financ Stud 14:1–27

Glaser M, Weber M (2007) Overconfidence and trading volume. Geneva Risk Insur Rev 32:1–36

Goetzmann WN, Kumar A (2008) Equity portfolio diversification. Rev Financ 12:433–463

Graham JR, Harvey CR, Huang H (2009) Investor competence, trading frequency, and home bias. Manag Sci 55:1094–1106

Granger CW (1969) Investigating causal relations by econometric models and cross-spectral methods. Econometrica 37:424–438

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M (2000) The investment behavior and performance of various investor types: a study of Finland’s unique data set. J Financ Econ 55:43–67

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M (2001) How distance, language, and culture influence stockholdings and trades. J Financ 56:1053–1073

Grinblatt M, Keloharju M (2009) Sensation seeking, overconfidence, and trading activity. J Financ 64:549–578

Kirilenko A, Kyle AS, Samadi M, Tuzun T (2017) The flash crash: high-frequency trading in an electronic market. J Financ 72:967–998

Kirman A (1993) Ants, rationality, and recruitment. Q J Econ 108:137–156

Kyle AS (1985) Continuous auctions and insider trading. Econometrica 53:1315–1335

Lakonishok J, Maberly E (1990) The weekend effect: trading patterns of individual and institutional investors. J Financ 45:231–243

Lakonishok J, Shleifer A, Vishny RW (1992) The impact of institutional trading on stock prices. J Financ Econ 32:23–43

Lillo F, Miccichè S, Tumminello M, Piilo J, Mantegna RN (2015) How news affects the trading behaviour of different categories of investors in a financial market. Quant Financ 15:213–229

Lo AW (2004) The adaptive markets hypothesis. J Portf Manag 30:15–29

Lux T, Marchesi M (1999) Scaling and criticality in a stochastic multi-agent model of financial market. Nature 397:498–501

Mantegna RN (1999) Hierarchical structure in financial markets. Eur Phys J B-Condens Matter Complex Syst 11:193–197

Marotta L et al. (2015) Bank-firm credit network in Japan: an analysis of a Bipartite network. PloS One 10:0123079

Miller RG (1981) Simultaneous statistical inference, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag, New York

Morton de Lachapelle D, Challet D (2010) Turnover, account value and diversification of real traders: evidence of collective portfolio optimizing behavior. New J Phys 12:075039

Musciotto F, Marotta L, Miccichè S, Piilo J, Mantegna RN (2016) Patterns of trading profiles at the Nordic Stock Exchange. A correlation-based approach. Chaos Solitons Fractals 88:267–278

Newman M (2010) Networks: an introduction. Oxford university press, Oxford, UK

Nofsinger JR, Sias RW (1999) Herding and feedback trading by institutional and individual investors. J Financ 54:2263–2295

Odean T (1998) Are investors reluctant to realize their losses? J Financ 53:1775–1798

Odean T (1999) Do investors trade too much? Am Econ Rev 89:1279–1298

O’hara M (1995) Market microstructure theory (Vol. 108). Blackwell, Cambridge

Rosvall M, Bergstrom CT (2007) An information-theoretic framework for resolving community structure in complex networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104(18):7327–7331

Seru A, Shumway T, Stoffman N (2009) Learning by trading. Rev Financ Stud 23:705–739

Shiller RJ (2003) From efficient markets theory to behavioral finance. J Econ Perspect 17:83–104

Thaler RH (ed) (2005) Advances in behavioral finance (Vol 2). Princeton university press, Princeton, USA

Tumminello M, Miccichè S, Lillo F, Piilo J, Mantegna RN (2011a) Statistically validated networks in bipartite complex systems. PloS One 6(3):e17994

Tumminello M, Miccichè S, Lillo F, Varho J, Piilo J, Mantegna RN (2011b) Community characterization of heterogeneous complex systems. J Stat Mech P01019

Tumminello M, Lillo F, Piilo J, Mantegna RN (2012) Identification of clusters of investors from their real trading activity in a financial market. New J Phys 14(1):013041

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Musciotto, F., Marotta, L., Piilo, J. et al. Long-term ecology of investors in a financial market. Palgrave Commun 4, 92 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0145-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0145-1

This article is cited by

-

Market Ecology: Trading Strategies and Market Volatility

Computational Economics (2024)

-

Meta-validation of bipartite network projections

Communications Physics (2022)

-

Detecting informative higher-order interactions in statistically validated hypergraphs

Communications Physics (2021)

-

Detecting network backbones against time variations in node properties

Nonlinear Dynamics (2020)