Abstract

In the European Union (EU) multiple levels of governance interact in the design of public policies. Multi-level policies require a variety of evidence to define problems appropriately, set the right objectives and create suitable instruments to achieve them. How such a variety of evidence is used in practice, however, remains largely elusive. In 2013, the reformed EU Cohesion Policy brought about a sea change in the way governments must justify their investment priorities to support innovation and economic development. One of many new 'ex-ante conditionalities' sought to improve the design of regional innovation policies by putting strong emphasis on the underlying evidence base of policy strategies. A multitude of data sources had to be combined to meet this novel requirement in 120 regional and national strategy documents. Combining various data sources meaningfully was a necessary first step to engage with stakeholders from relevant business and research communities to jointly develop and decide on priorities for public investments. Stakeholder organisations had the opportunity to contest insights coming from official statistics. But how do governments reconcile insights from socio-economic analyses with differing views from stakeholders? We illustrate how such contestation of evidence has unfolded in the Basque Country. In this region, socio-economic analysis and broader stakeholder consultation rapidly confirmed three investment priorities that had been already quite established. Stakeholders from local governments, universities and other government departments contested this choice as not fully representative of the local potential and societal needs. Through their participation in a multi-stakeholder body advising the government they succeeded in adding four priorities that address local societal issues: sustainable food, urban living, culture and environmental protection. Our findings underline that rational planning using statistics gets governments only so far in meeting pressing societal challenges. Stakeholders contesting and complementing statistical insights make policies more responsive to local needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

The elusive search for evidence in a multi-level Europe

At a time when “post-truth” has become the term of the year, the role of evidence in the policy process is ever more contested and questioned. Citizens and concerned social groups increasingly demand justifications for why governments prioritise some issues over others. The European Union (EU) with its annual budget at EUR 145 billion (2015 figures), split into six different headings, has made prioritisation of public investments and their strategic use a guiding principle for its multi-annual budget 2014–2020. Being arguably the most complex socio-political and economic space in the world (Hooghe and Marks, 2001), in the EU various levels of government and different types of organisations interact and contribute evidence to develop priorities and implement public policies. Having a highly elaborated system of harmonised collection of official statistics assembled by Eurostat, in addition to various governmental and private databases, creates a large and scattered picture of available evidence. While national statistics are abundant, more detailed and timely subnational or place-based data is rather scarce (Kleibrink and Mateos, 2017). How combinations of these data sources are used to justify policy choices in the EU’s system of multilevel governance, however, has not been studied in a systematic way. Case studies have been often used to develop typologies of policy appraisal systems that improve the evidence base of decisions (Nilsson et al., 2008). Yet such studies are less suited when evidence is used as a first step to inform collaborative decision-making with concerned non-governmental stakeholders, a process increasingly common across policy domains (Ansell and Gash, 2008; Fung, 2006). Our findings identify two different uses of evidence. The Basque government used quantitative evidence to legitimate past decisions and policy revisions. Stakeholder views, on the other hand, were more relevant during exploratory policy deliberations that defined new priority domains addressing societal challenges.

The EU’s Cohesion Policy, constituting the largest part of the EU budget, addresses regional development issues. It has become a highly structured process with strong requirements for ex-post and ex-ante evaluations to justify public investment decisions and demonstrate thematic concentration. The implementation track record has not lived up to the expectations, while public scrutiny has been increasing. In great part a “lack of conceptual thinking or strategic justification for programmes” over the past 20 years explains why spending has not been as effective as intended (Bachtler et al., 2016, p. 20). Therefore, a series of legal ex-ante conditionalities were introduced in 2013 to improve policy execution by requiring sound policy and regulatory frameworks and stronger administrative capacities. Improving these aspects of policy-making has imposed, in many cases, high demands on the quality of evidence used to justify choices. In total, 36 ex-ante conditionalities were introduced (European Parliament and Council, 2013).

Administrations at national, regional and local level that did not comply with this legal provision, either due to late submissions or issues concerning the quality of submitted documents, had to negotiate actions plans with the European Commission. These included binding indications of the actions undertaken to remedy shortcomings with a clear deadline by the end of 2016 to achieve full compliance (European Parliament and Council, 2013). The difficulty of this task is reflected by the sheer number of action plans addressing the fulfilment criteria spelled out in the regulation further below, amounting to 658 distinct action plans.Footnote 1

In this article, we examine one of these conditionalities that mandated the design and adoption of evidence-based innovation strategies for 'smart specialisation'. Innovation policies are a critical example of evidence-based policy-making, since they try to look into the future and create a shared understanding of what will be successfully commercialised or put into practice in local, national and global markets. In other words, these policies create shared visions of future competitive advantages (Beckert, 2016). What this requirement meant in practice is enshrined in the relevant EU regulation (European Parliament and Council, 2013):

'Smart specialisation strategy’ means the national or regional innovation strategies which set priorities in order to build competitive advantage by developing and matching research and innovation own strengths to business needs in order to address emerging opportunities and market developments in a coherent manner, while avoiding duplication and fragmentation of efforts; a smart specialisation strategy may take the form of, or be included in, a national or regional research and innovation (R&I) strategic policy framework; … [it] shall be developed through involving national or regional managing authorities and stakeholders such as universities and other higher education institutions, industry and social partners in an entrepreneurial discovery process.

The regulation lists several fulfilment criteria that the European Commission used to formally assess compliance with these provisions: The innovation strategy should be adopted at the highest political level of the region or state, be 'based on a SWOT or similar analysis to concentrate resources on a limited set of research and innovation priorities', outline 'measures to stimulate private research, technology and development investment', contain 'a monitoring mechanism' and a finance plan. Action plans were required if administrations did not manage to submit their full strategy documents by the time of programme approval (which was the case for 21 member states) or the Commission believed the submitted documents did not meet the fulfilment criteria set out in the regulation. Governments resorted to a vast array of different information sources to comply with these requirements.

Ninety-three distinct action plans had to be implemented to rectify issues raised by the European Commission and to meet the fulfilment criteria of smart specialisation. Economists developed the underlying concept of smart specialisation during their work in an EU expert group (Foray et al., 2009). Smart specialisation describes the 'capacity of an economic system (a region for example) to generate new specialities through the discovery of new domains of opportunity and the local concentration and agglomeration of resources and competences in these domains' (Foray 2015, p. 1). In this view, public policies must involve all relevant organisations in the local innovation system—firms, research organisations, universities and civil society—to define these opportunity domains, prioritise funding to support them and coordinate actions to further develop them in order to transform the economy. How fast this concept entered into the new Cohesion Policy is surprising, especially since the risks and benefits from specialising in certain economic activities are under debate and largely depend on the local linkages across sectors (Balland et al., 2018).

In the remainder of this article, we focus on one particular dimension of smart specialisation, namely the evidence used to justify the prioritisation of public investments. The overabundance of statistical data can be understood as ‘aggregated facts’. Yet most policy-making for place-based policies such as innovation and economic development requires more detailed and oftentimes territorial data. Concerned non-governmental stakeholders can serve as critical challengers of official statistics by giving feedback on what may be missing or misleading in this aggregated picture, possibly also pointing to causal stories that the data does not cover. We argue that bridging these two worlds is not a trivial process, putting great demands on governmental agencies to analyse the interaction between aggregated facts and stakeholder knowledge. The EU’s smart specialisation conditionality in general, and the experience of the Basque Country specifically, illustrate how this interplay has unfolded to adjust policy choices to societal demands.

Quantifying evidence and stakeholder knowledge

Governments must quantify different aspects of their societies to effectively manage socio-economic and political relations. State administrations rose to be the number one data collector, originally to raise taxes on land and transactions and steer economic development (Mayntz, 2017; Scott, 1998). Using quantified evidence has become a prerequisite for shaping socio-economic realities and coping with publicly relevant problems, suggesting the existence of objective and precise knowledge to make public policies both more effective and legitimate (Mayntz, 2017). In the 1960’s, the Rand Corporation’s formalisation of a sophisticated Planning, Programming, and Budgeting System constituted the heyday of rational planning, which was resurrected again in the 1980s and 1990s with the idea of new public management. In part, this branch of thinking continued in what we now call the evidence-based policy movement (Boswell, 2017; Cairney, 2016; Cartwright and Hardie, 2012; Head, 2010; Khagram and Thomas, 2010).

At the same time, there is mounting criticism of the idea that numbers should be the predominant or even sole component of ‘evidence’. Management scholars summarised this contention succinctly with the dichotomy ‘hard versus soft data’. Early on, Mintzberg (1994, 1978) convincingly argued that hard data, or 'quantitative aggregates of detailed facts', are rarely useful for planning and implementing strategies in the real world. They often aggregate variant quantities and details that measure very different aspects of social reality. In the worst case, hard data constructs ambiguous phenomena as objective facts built through standardised methodologies that defy local and contextual knowledge (Irvine et al., 1979; Mügge, 2016; Pearce et al., 2014). Unlike the assumption that rational plans with clear causal relations can be made and their effects measured, reality is more fuzzy and blurred. In contexts where issues and strategies are emergent rather than fixed, 'soft data' or stakeholder perceptions and interactions become equally important.

In many important policy domains such as education, health, welfare, science and technology and industrial and economic development, quantification and hard data have become central in justifying policy choices and prioritisation. Yet, the quality of this data is often left unquestioned (Mayntz, 2017, p. 8). Furthermore, the more detailed information is needed, the more difficult it becomes to gather that kind of data. Data availability is not the only problem, however. Whether data abounds or is scarce, many local and regional administrations do not have sufficient competencies to analyse overly complex or unstructured data. Within oftentimes devolved governments, analytical capacities are often unevenly distributed, thus aggravating sound policy analysis (Borrás, 2011; Borrás and Jordana, 2016).

This is where soft data and stakeholder involvement come into the picture. They can contest the apparently transparent and objective nature of hard facts, and contribute to more inclusive policy-making that takes full account of stakeholder knowledge and needs. Evidence must be contestable in democratic systems, taking into account the political nature of decision-making and the need to institutionalise contestation and knowledge transfer from hard data and its analysis (Parkhurst, 2017). A multitude of stakeholders that are targets of policy programmes challenge evidence. Institutionalised stakeholder contestation can partly compensate for the lack of relevant data or limited administrative capacities for dealing with complex data in the public sector.

The interplay of hard and soft data in smart specialisation

Starting with the EU level and working down to the national and subnational or regional level, the availability of data that is relevant for innovation policies varies significantly. At the European level, data usually concentrates on EU-wide objectives, like building the European Research Area or becoming an 'Innovation Union'. Various scoreboards benchmark the performance of EU member states and regions (Arundel and Hollanders, 2008). Harmonised data collection coordinated through Eurostat facilitates this process (OECD and Eurostat, 2005). At national level, detailed accounts report, for instance, on structural business statistics of employment and productivity by sector. Such data can be broken down to the regional level, depending on the practices and capacities of national statistical offices. In other words, regional administrations usually depend on national level bodies for data that is an important source for their usually place-based policies. Only very few regional administrations benefit from their own statistical offices that produce highly detailed data; exceptions are economically advanced regions like Baden-Württemberg and the Basque Country. Non-territorialised data at the level of aggregate industrial sectors thus is over-abundant, while place-based and industry-specific data is often still scarce (Kleibrink and Mateos, 2017).

How can governments make sense of this multitude of available information to build stronger evidence for their innovation policies, while considering the preferences and views of critical stakeholders such as companies, business associations or research institutes? The European Commission supported governments in this endeavour by organising peer review workshops, building thus on the accumulated experience from the open method of coordination through which national governments could learn from each other on how to improve their policies. In the EU’s Cohesion Policy, peer reviews among policy-makers have become an important tool for coordination.Footnote 2 Apart from the broader Cohesion Policy, smart specialisation received tailored support through peer reviews.

One hundred and twenty national and regional administrations submitted their strategies in the end to the European Commission. Since 2012, 54 regional and national administrations that had to comply with the smart specialisation requirement voluntarily underwent a peer review to present their ongoing strategy-making processes to peer policy-makers from other EU regions and member states, discuss common problems and commit to tangible actions to improve.Footnote 3 This exercise covered thus almost half of those that submitted their strategies. Peer reviews have become a central process to support learning for designing strategic aproaches to place-based innovation policies across EU regions. Administrations were encouraged to consider novel ways to move towards participatory whole-of-government thinking and action, often supported by external expert advice. When evidence is used to justify local policy choices and hence public investments—who gets what and why—internal voices may either restrain from being too critical towards anybody or they may not be perceived as trustworthy sources. Bringing in a trusted external expert can break up established ways of policy thinking and parochial practices. Out of the peer reviewed regions and countries, 46% had to prepare an action plan to remedy shortcomings.Footnote 4 The majority did not have to do further work on their documents. In a survey, a vast majority of peer review participants assessed the exercise to be useful, one fifth made substantial changes to their strategy processes after receiving feedback, while half of participants introduced some smaller changes after the workshop (Midtkandal and Hegyi, 2014). As mentioned earlier, 93 distinct action plans had to be adopted for the 120 strategy documents that were initially submitted to the European Commission. Roughly only one third of all countries and regions passed without any action plan.

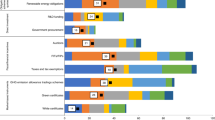

What happened in the European arena in terms of transnational learning and exchange, however, was only the tip of the iceberg. Thousands of data sources and stakeholder workshops were organised across the EU in regions and member states. The most commonly used participatory methods to involve stakeholders were working and focus groups, interviews and online surveys (Griniece et al., 2017). To create a shared vision between government and non-governmental stakeholders, working and focus groups were more prominent than statistical analysis. Other studies based on surveys of policy-makers find similar results, suggesting that most administrations used both informational and interactive approaches to define their strategic objectives. In many cases, established procedures and organisational structures had to be changed to allow for this combined approach (Marinelli and Periáñez Forte, 2017). Quantitative analyses thus prepared the ground for the democratic contestation of stakeholders (see also Boswell, 2017, p. 13). In the next section, we illustrate how this contestation unfolded in the Basque Country, where the regional government first established priority domains based on socio-economic analysis. Universities and local governments successfully contested this draft strategy and managed to include additional priority domains that in their view were critically linked to local culture and societal needs.

Constructive contestation of evidence in the Basque Country

The process of policy design and implementation in the Basque region is an illustrative example of how evidence has been used for different purposes throughout different phases of prioritising public investments. The Basque Country is a region located in Northern Spain that has singular characteristics with respect to other regions in Europe. Its regional government has its own powers and shares competences with the national state in some policy domains. Innovation policy is a domain in which the regional government can act autonomously within the overarching national framework. This section builds on different sources and data. It is based on document analysis of the Science, Technology Plans (STIP 2015 and 2020) and related texts that document the process of developing the current policy framework.Footnote 5 Additionally, the authors had access to internal documents (intermediate versions of the strategy; minutes of meetings among different actors) and were involved in parts of the discussions through 'engaged research projects'.Footnote 6

The Basque framework for smart specialisation was accepted without any action plan by the European Commission, reflecting the tradition of policy planning in the regional government that builds on strong data analysis capacities and stakeholder networks. Six regional organisations have primarily provided ‘hard’ data for this strategy process. Already in the 1980’s, the Basque government created the regional statistics agency EUSTAT that has been collecting and analysing regional data. Policy-makers have been systematically using its data and analyses. Additionally, the Basque government has promoted different organisations at different times, each one with a specific role in evidence gathering and analysis.

In 1981, the Basque government established the Business Development Agency SPRI, a public corporation responsible for managing funds and programmes of the government’s Industry Department. It gathers data on these programmes and the beneficiaries. It is noteworthy that the focus of Basque innovation policy has been on industry and manufacturing. Therefore, this department has managed a greater amount of funds compared to the Education and Science Department. The latter coordinates policies for universities and research organisations through another agency, Ikerbasque, that supports science activities in the region and provides the government with relevant data.

Innobasque, the Basque innovation agency founded in 2007 by the President’s Office, has had an important role in innovation policy and especially in the development of the new smart specialisation strategy. It supported the government as a technical secretariat throughout the process. One of its missions is to evaluate innovation policies and the regional innovation system. Innobasque has promoted and carried out several analyses and diagnoses that informed policy-making in this regard.

Orkestra-the Basque Institute of Competitiveness is a non-profit research centre whose mission is to improve Basque competitiveness through regional analysis and research-based policy advisory services. Finally, the consulting company B + I Strategy supported the Government in designing the strategy through analysis and drafting of the first policy documents.

All these regional organisations have been actively building the evidence base for the Basque smart specialisation strategy—albeit mainly based on hard data with only little soft data used during the earlier stages of the process. Indeed, some of these organisations (Orkestra, B + I Strategy and Innobasque) took part in the Inter-departmental Committee in charge of coordinating the strategy process, together with regional policy-makers from different departments of the Basque Government and SPRI.

The mosaic of the Basque policy landscape for innovation support is completed by the stakeholder organisations that are catalysts and beneficiaries of policy programmes. They complemented and contested the evidence and hard data presented by the government agencies, offices and advisory bodies we listed before. Representatives of these organisations are members of the Basque Science, Technology and Innovation Council (BSTIC), a multi-stakeholder body that has been steering regional innovation policies since 2007. This Council, whose main responsibility was to approve and validate the STIP 2020 in which the priorities were included, was at the same time one of the main fora for discussing and contesting evidence. In what follows, we briefly describe the variety of regional stakeholders that have provided evidence in regional policy-making in different ways:

-

Subregional governments: The Basque region is divided in three provinces, each of which has its own administration with competences in certain areas that affect innovation policy such as economic development or taxation. Only two regions in Spain have their own taxation powers, derived from medieval rights or fueros: the Basque Country and Navarra. Additionally, city governments have local development agencies that act as catalysers of economic activities. All these actors collect data and evidence. They have their own policy-making processes and priorities that interact with the Basque smart specialisation process, making multi-level governance a key issue in the region.

-

Technology organisations: Technology centres, mainly a strategic platform named IK4 that associates several technology research centres and Tecnalia, are cornerstones of the Basque innovation system. They have conducted research in collaboration with Basque firms and supported their technological developments since the 1980’s and are very active in EU consortia. These organisations constitute a rich source of information. They are thermometers that indicate how competitive Basque firms are in different domains and measure hot European trends in these domains.

-

Higher education institutions: In the Basque region three universities are veritable heavyweights. The public University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU) is the biggest and most comprehensive university. It covers a wide range of knowledge areas. The other two universities are private, Mondragon University and Deusto University, and differ by their peculiar specialisations and missions. Mondragon University mainly serves as a training institution for the Mondragon Corporation, an industrial group made up of more than 100 cooperatives in the Basque region. Engineering and advanced services to firms are their main activities. Deusto University, for its part, has its main strength in social sciences, although it also covers other areas such as engineering. Orkestra, the regional research and advisory institute mentioned previously, is linked to this university through the Deusto Foundation.

-

Scientific organisations: It is important to distinguish between two groups of research organisations outside universities—cooperative research centres (Centros de Investigación Cooperativa or CIC) and the Basque Excellence Research Centres (BERCs). Although they are very different, both are linked to the Basque innovation priorities. CICs were created to support Basque sectoral strategies such as the ones in bioscience, energy and nanoscience. Their main aim is to build scientific capabilities in those areas. BERCs, on the other hand, conduct basic research in transversal knowledge areas like mathematics, language or climate. Both types of organisations played a key role in the prioritisation process.

-

Businesses: Firms in the Basque region play a significant role in innovation policy, especially industrial firms, given the importance of manufacturing. Most of the firms are small and medium-sized enterprises with a relatively small number of employees. Large companies, by their sheer size and economic importance, are better equipped to present their positions to policy-makers and contest evidence. This is particularly true for the energy sector. However, the Basque industrial panorama cannot be understood without considering the central role cluster associations have in the region. These associations have been critical for innovation policy-making and especially in the implementation of the current smart specialisation strategy. They constitute an important source of evidence, both in terms of hard data about their associates and the sectors they represent as well as regarding the strategic reflections that have taken place in their working bodies.

The variety of actors, institutions and the complex governance of the innovation policy in the Basque Country, coupled with abundant hard data, make the process of policy-making and prioritisation a very difficult and delicate task.

Using evidence for policy design to justify priorities

As recognised by the Basque government but also by external expert assessment, Basque innovation policies have had some of the ingredients of participatory and evidence-based policy-making for more than 30 years (Morgan, 2013). When the concept of smart specialisation was established as a legal requirement in the European Union, the Basque Country took this as an opportunity to revise its prioritised innovation domains, despite already having a widely recognised policy framework in place: the Science, Technology and Innovation Plan 2015 together with singular strategies for three priority domains—Biobasque for biosciences, Energibasque for energy and Nanobasque for nanosciences—and a dedicated cluster policy (Aranguren et al., 2016). STIP 2015 was elaborated in a very participatory and inclusive way with evidence not only from hard data and statistics but also through the participation of a wide array of relevant Basque stakeholders (Morgan, 2013). These documents already had some elements of evidence-based policy prioritisation. They were developed in the previous decade through data analyses coupled with a highly participatory and inclusive process in which many relevant stakeholders of the innovation system were consulted. These previous processes gave legitimacy to some of the areas that finally constituted the priority areas of the new smart specialisation strategy.

Previous processes to develop STIP 2015 paved the way for the ensuing prioritisation process that the Basque Government conducted for the STIP 2020, the main document that reflects the regional smart specialisation strategy. Thus the work to comply with the EU provision did not start from scratch. The Basque government decided to begin the new prioritisation process first internally within the public sector, with the collaboration of different departments from the government and some external organisations such as Innobasque and Orkestra. Orkestra provided evidence through analysis but also through an external assessment of the first steps of the prioritisation process. In addition, the Basque government presented their on-going work at the first peer review workshop organised by the European Commission in early 2012.Footnote 7 During this workshop, the government asked for feedback on five challenges: (1) how to establish global partnerships and innovative products in priority domains, (2) how to support the internationalisation of small and medium-sized enterprises, (3) how to promote cooperation across different business clusters, (4) how to motivate universities to participate in strategic partnerships, and (5) how to reach smaller and rather non-innovative companies and include them in the strategic action. Together with policy-makers from other regional governments from the Netherlands, Romania and France, the Basque representatives discussed these and other issues and how to address them back home.

These external views helped the government to legitimise its on-going process and get feedback for possible improvements. Prioritisation thus clearly built on previous policy frameworks. At the same time, the government used the opportunity to address some of the weaknesses and inefficiencies of the regional innovation system (Aranguren et al., 2016). During this phase, the Basque government established the following four criteria to define research and innovation priorities for the region:

-

1.

Presence of competitive business activities that can generate employment and added value in the region.

-

2.

The existence of significant technological and scientific capabilities related to these activities and linked to key enabling technologies such as advanced manufacturing and biotechnology.

-

3.

Promising new domains or 'opportunity niches' must have a minimum level of competitive businesses and technological and scientific capabilities.

-

4.

The existence of private and public instruments to support priority domains.

Different sources were analysed to assess whether these pre-established criteria were met. The following three steps illustrate how this was done in practice:

-

Data on business structure, sectoral growth and exports was analysed and specialisation indexes to define priority sectors were constructed.

-

Indicators of the size of scientific and technological organisations, their quality and their results were examined to benchmark existing capabilities.

-

The potential impact on society and added value were assessed, as well as the expected market growth, to identify new opportunities.

Whereas the first two analyses were mainly quantitative the last one was carried out through qualitative analysis. The main sources were official statistics from the European and regional statistical offices as well as data and analyses from involved stakeholders (cluster reports, Orkestra policy publications, government reports etc.). Finally, relevant studies by international organisations, especially from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, were systematically examined. All these analyses culminated in the identification of three priority areas: bioscience-health, energy and advanced manufacturing (Basque Industry 4.0). This definition was part of the main policy documents developed by the Inter-departmental Committee between autumn 2013 and spring 2014. BSTIC approved the final strategy document in April 2014. After that, a Scientific Committee contributed minor changes to the document in October 2014 and the formal process of consultation with other actors in the Basque Country started in the beginning of 2015.

Although it appears to have been a top-down process at first sight, the strategy had changed significantly due to the contestation of existing evidence within only 6 months. The analyses of hard data suggested that the priorities for the Basque Country ought to be energy, health and advanced manufacturing, all established economic sectors that are competitive in the EU. Following feedback from key stakeholders such as universities, local government and other departments it was decided to add four ‘opportunity niches’ that are strongly linked to the regional territory: sustainable agri-food industry; leisure, entertainment and culture; urban planning and regeneration; and environmental ecosystems. This inclusion was largely a consequence of the contestation by some vital stakeholders. Representatives of Basque universities and Provincial Councils contested the orientation of the strategic priorities during a meeting of the BSTIC in autumn 2013. In another meeting held in December that year, participants entered into an informal dialogue with selected stakeholders and channelled their views later on into the formal process. Finally, a representative of the Department of Education, Language Policies and Culture suggested the inclusion of ‘language industries’ in the opportunity niche for culture in April 2014, just before the final strategy document was approved. It is worth remembering that this department has substantially less funding than the more powerful Industry Department. Nonetheless, their representative was still able to convince the Council members to add language as a dedicated sub-priority. The stakeholder views stressed that the potential impact on the local society must be taken more into account in funding decisions.

In summary, the Basque government was the main actor in this phase of revisiting existing priorities for innovation and adapting them for a new policy design. Learning from previous processes and making explicit reference to them was an important element that complemented the use of data and analysis to legitimise policy decisions across the innovation system. This shaped substantially the definition of policy priorities and the new innovation strategy. However, the governance mechanism of the innovation strategy allowed formal and informal processes of contestation of this ‘hard’ evidence. Particularly the Science, Technology and Innovation Council has been instrumental in translating societal demands into the definition of regional priorities.

Evidence during policy implementation: challenges ahead

The definition of policy priorities is only the first step of this strategy process. After the approval of STIP 2020, implementation began. While in the first phase of policy design the government was the central actor, in the implementation phase other organisations such as cluster associations, technology centres and universities moved centre stage. The Basque government has established steering groups co-led by stakeholders to manage implementation and collect evidence. For instance, the innovation manager of one of the industrial companies in the Basque Country is co-leading the priority domain for advanced manufacturing, together with the Ministry of Economic Development and Infrastructure. The mission of these steering groups is to further define and make tangible the priorities and translate them into project portfolios that are strategic for the region. Subregional governments are embedded in these groups to align strategies across different governance levels.Footnote 8

Policy implementation, too, is informed by evidence. Evidence and data from different organisations constitute the main source to feed the discussions of steering groups and other related groupings. They are facing two key challenges regarding hard data. First, implementation of the strategy must be overseen by a monitoring mechanism that allows policy-makers to effectively manage and adapt goals and measures based on progress on the ground (Kleibrink et al., 2016). Policy monitoring and evaluation or knowing ‘what works’ is a pending issue on which some progress has been made in the past few years (Morgan, 2013). One of the difficulties is to identify which indicators truly measure what is relevant and to agree on a shared understanding of their interpretation with relevant stakeholders. This requires not only political commitment, but also availability of detailed data to monitor progress made in each priority domain. This leads us to the second challenge, namely collecting data and information on detailed ‘priority domains’ instead of established industrial sectors. There are, for example, established industry codes to classify economic activities in the production of air and spacecraft, but none for advanced manufacturing or biopharmaceuticals. Official statistics are generally organised around established economic sectors, both in the Basque Country and beyond. At European level attempts were made to address these challenges though the European Cluster Observatory that uses statistical measures to group 'emerging industries' (Ketels and Protsiv, 2014). Yet there is still a long way to go to systematically cope with this issue. This opens up room for the use of more qualitative approaches of participatory monitoring and evaluation.

Conclusions

Governments use different combinations of evidence at different points in time of the same policy process. We shed light on the various kinds of evidence and how policy-makers use them to improve the quality of policy design. How can governments justify what is a priority for public action and what is not? Simply looking at the widely studied science-policy interface and use of academic research to inform policy-making largely misses this more pertinent question (Newman, 2017). We argue that the key issue is not which evidence to use or whether policy analysts should take a more quantitative or qualitative position. Rather, we show with our case study on the Basque Country how different types of evidence feed into policy processes in different phases and for different purposes. This evidence has been intrinsically related to governance mechanisms and multi-stakeholder bodies in this region.

In the European Union, a new ex-ante conditionality was introduced to ensure sound policy frameworks and stronger administrative capacities for investing EU funds in support of science, technology and innovation. Creating a strong and participatory evidence base was a cornerstone of this legal requirement. National and regional governments developed and adopted one hundred and twenty innovation strategies that had to comply with these principles. Evidence had to underpin policy prioritisation and the strategy process had to enable democratic contestation from concerned stakeholder groups. This iterative process has unfolded in very different ways across the European Union. The European Commission negotiated 427 action plans with national and regional governments, in part to remedy shortcomings in their evidence base. Over a period of 5 years, different Commission services offered support to administrations to fully comply with these new provisions. Their activities supported policy learning, contributed to convergence between public investment priorities and broader EU objectives, promoted participatory whole-of-government thinking and provided an external view to legitimise domestic policy choices.

The Basque case, where one of these strategy processes unfolded, vividly illustrates the varieties of evidence policy-makers use and how they eventually can become effective stories for innovation and local economic development. It shows that quantitative evidence was more frequently used to legitimise decisions when revisiting and (re-)designing policies, while ‘soft’ data and stakeholder contestation were employed more during exploratory policy deliberations to define new priority domains linked to societal challenges. Different public and private organisations played diverse roles in gathering, analysing and contesting evidence throughout the policy process for developing a new innovation strategy. These roles do not only depend on their institutional nature (private/public), but also on their positions and participation in the governance of the strategy. The weight and power of stakeholders in policy-making was determined by governance structures and mechanisms. This is more likely to be the case in regions with a long history in innovation institutions and policies, since established institutions generate trust among stakeholders and new policies necessarily build on previous ones (Kramer, Tyler and Powell, 1996).

An important bottleneck which is notable for subnational administrations is their limited capacity to regularly conduct timely policy analysis of quantitative data and stakeholder feedback, which requires substantial analytical skills and resources. In the Basque case, the existence of knowledge organisations with expertise in policy design and innovation policy constituted an advantage. More research is needed to better understand the role renowned external experts can play to help governments in promoting impartiality and openness to external viewpoints and novel ideas. Other mechanisms to achieve this are peer reviews, dialogue formats in which policy-makers from different regions and countries discuss similar problems and possible solutions. Policy-making, after all, is an iterative process in which large amounts of information and evidence come in at different moments, making a systematic and inclusive approach necessary to make informed decisions for policies that are more responsive to societal needs.

Notes

Data on these action plans was retrieved on 2 February 2018 from the internal SFC2014/Infoview database managed by the Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy of the European Commission.

Apart from peer reviews of smart specialisation strategies, the European Commission introduced a new tool called TAIEX REGIO PEER 2 PEER to improve administrative capacities for ERDF and the Cohesion Fund; see http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/policy/how/improving-investment/taiex-regio-peer-2-peer/ (accessed on 7 February 2018).

Information on peer reviews was taken from the European Commission’s dedicated website: http://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/s3-design-peer-review.

Own calculation based data from the internal SFC2014/Infoview database and the list of peer reviewed regions retrieved from the website of the Smart Specialisation Platform of the European Commission.

The official minutes of the Basque Science, Technology and Innovation Council are publicly available: http://www.euskadi.eus/web01-a2lehpct/es/contenidos/informacion/consejo_vasco_de_cti/es_def/index.shtml.

In engaged research projects researchers generate knowledge by interacting with involved stakeholders, in this case with regional policy-makers.

The presentation of the Basque government can be found here: http://s3platform.jrc.ec.europa.eu/regions/es21 (accessed on 15 February 2018).

More information about this priority domain can be found at https://www.innobasque.eus/microsite/basque-industry-40/que-hacemos/ (accessed 15 February 2018).

References

Ansell C, Gash A (2008) Collaborative governance in theory and practice. J Public Adm Res Theory 18:543–571. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mum032

Aranguren MJ, Morgan K, Wilson J (2016) Implementing smart specialisation: the case of the Basque Country, Cuadernos Orkestra. Orkestra—Basque Institute of Competitiveness, San Sebastián

Arundel A, Hollanders H (2008) Innovation scoreboards: indicators and policy use. In: Nauwelaers C, Wintjes R (eds) Innovation policy in Europe: measurement and strategy. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, p 29–52

Bachtler J, Begg I, Charles DR, Polverari L (2016) The Long-term effectiveness of EU cohesion policy: assessing the achievements of the ERDF, 1989–2012. In: Bachtler J, Berkowitz P, Hardy S, Muravska T (eds) EU cohesion policy: reassessing performance and direction. Routledge, London, p 11–20

Balland P-A, Boschma R, Crespo J, Rigby DL (2018) Smart specialization policy in the European Union: relatedness, knowledge complexity and regional diversification. Reg Stud. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1437900

Beckert J (2016) Imagined futures: fictional expectations and capitalist dynamics, 1st edn. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Borrás S (2011) Policy learning and organizational capacities in innovation policies. Sci Public Policy 38:725–734. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234211X13070021633323

Borrás S, Jordana J (2016) When regional innovation policies meet policy rationales and evidence: a plea for policy analysis. Eur Plan Stud 24:2133–2153. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1236074

Boswell J (2017) What makes evidence-based policy making such a useful myth? The case of NICE guidance on bariatric surgery in the United Kingdom. Governance. https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12285

Cairney P (2016) The politics of evidence-based policy making. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Cartwright N, Hardie J (2012) Evidence-based policy: a practical guide to doing it better, 1st edn. Oxford University Press, Oxford; New York

European Parliament and Council (2013) Regulation (EU) No 1303/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down common provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund and laying down general provisions on the European Regional Development Fund, the European Social Fund, the Cohesion Fund and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund. Brussels

Foray D, Hall B, David PA (2009) Smart specialisation: the concept. Knowledge Econ Policy Brief

Foray D (2015) Smart specialisation: opportunities and challenges for regional innovation policy. Routledge, Abingdon; New York

Fung A (2006) Varieties of participation in complex governance. Public Adm Rev 66:66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

Griniece E, Rivera León L, Reid A, Komninos N, Panori A (2017) State of the art report on methodologies and online tools for smart specialisation strategies, Report produced in the framework of the Horizon 2020 project Online S3: ONLINE Platform for SmartSpecialisation Policy Advice

Head BW (2010) Reconsidering evidence-based policy: key issues and challenges. Policy Soc 29:77–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2010.03.001

Hooghe L, Marks G (2001) Multi-level governance and european integration. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham

Irvine J, Miles I, Evans J (1979) Demystifying social statistics. Pluto Press, London

Ketels C, Protsiv S (2014) Methodology and findings report for a cluster mapping of related sectors, European cluster observatory report. European Commission, Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry, Brussels

Khagram S, Thomas CW (2010) Toward a platinum standard for evidence-based assessment by 2020. Public Adm. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2010.02251.x

Kleibrink A, Gianelle C, Doussineau M (2016) Monitoring innovation and territorial development in europe: emergent strategic management. Eur Plan Stud 24:1438–1458

Kleibrink A, Mateos J (2017) Searching for local economic development and innovation: a review of mapping methodologies to support policymaking. In: Reference module in earth systems and environmental sciences, edited by Bo Huang, Kai Cao, and Elisabete A. Silva, 59–68. Elsevier, Amsterdam; Oxford;Waltham MA. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-409548-9.09674-3

OECD, Eurostat (2005) Oslo manual: guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation data. OECD Publishing, Paris

Powell WW (1996) Trust-based forms of governance. In: Kramer RM, Tyler TR (eds) Trust in organizations. SAGE, Thousand Oaks, p 51–67

Marinelli E, Periáñez Forte I (2017) Smart specialisation at work: the entrepreneurial discovery as a continuous process. S3 Working Paper Series No. 12/2017. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Mayntz R (2017) Zählen—Messen—Entscheiden: Wissen im politischen Prozess [Counting—measuring—deciding: knowledge in the political process]. MPIfG Discuss, Cologne. Pap. 17

Midtkandal I, Hegyi FB (2014) Taking Stock of S3 peer review workshops (No. JRC92890), S3 working paper series 07/2014. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Mintzberg H (1994) The rise and fall of strategic planning: reconceiving roles for planning, plans, planners. Free Press; Maxwell Macmillan Canada, New York; Toronto

Mintzberg H (1978) Patterns in strategy formation. Manag Sci 24:934–948

Morgan K (2013) Basque Country RIS3: an expert assessment on behalf of the directorate-general for regional and urban policy (No. Contract Number CCI 2012CE160AT058)

Mügge D (2016) Studying macroeconomic indicators as powerful ideas. J Eur Public Policy 23:410–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2015.1115537

Newman J (2017) Debating the politics of evidence-based policy. Public Adm 95:1107–1112. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12373

Nilsson M et al. (2008) The use and non-use of policy appraisal tools in public policy making: an analysis of three European countries and the European Union. Policy Sci 41:335–355

Parkhurst JO (2017) The politics of evidence: from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence. Routledge, Abingdon

Pearce W, Wesselink A, Colebatch H (2014) Evidence and meaning in policy making. Evid Policy 10:161–165. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426514X13990278142965

Scott JC (1998) Seeing like a state: how certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press, New Haven

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. The views expressed are purely those of the authors and may not in any circumstances be regarded as stating an official position of the European Commission.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kleibrink, A., Magro, E. The making of responsive innovation policies: varieties of evidence and their contestation in the Basque Country. Palgrave Commun 4, 74 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0136-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-018-0136-2