Abstract

Hurricane Maria was the worst recorded natural disaster to affect Puerto Rico. Increased stress in pregnant women during and in the aftermath of the hurricane may have induced epigenetic changes in their infants, which could affect gene expression. Stage of gestation at the time of the event was associated with significant differences in DNA methylation in the infants, especially those who were at around 20–25 weeks of gestation when the hurricane struck. Significant differences in DNA methylation were also associated with maternal mental status assessed after the hurricane, and with property damage. Hurricane Maria could have long lasting consequences to children who were exposed to this disaster during pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Puerto Rico (PR) is an archipelago in the Eastern Caribbean with a population of approximately 3.3 million1. It has been an un-incorporated territory of the United States since 1898 characterized by high poverty rate (43%) and high income inequality2. The island is burdened by significant public health problems, including one of the highest prevalence rates of premature births in the United States (11.8%, 2020) and worldwide3,4, and a high incidence of HIV infections. The Zika epidemic also affected the island5.

On September 20 of 2017, PR was devastated by Hurricane Maria, a category 4 storm that affected the entire island. Two weeks earlier, Hurricane Irma, a category 5 storm had passed very close to the island causing significant damage on the infrastructure. The storms completely wiped-out the island’s electric power infrastructure, water supplies, communications, and transportation systems (including all ports and airports), leaving many residents isolated for several weeks. By November 2017, two months after the storm, only 50% of the electric power generation had been restored, and 10% of the citizens were still without water service; by February 2018, only 70% of the electric power generation capacity had been restored5. In October 2017 it was estimated that there were 51 deaths directly caused by the hurricane, and an additional 900 potentially hurricane-related deaths. Subsequent studies estimated that the “excess all-cause deaths” in Puerto Rico during the three months following Hurricane Maria could amount to more than 40006.

Although it is far too soon to estimate the public health consequences of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, pregnant women were an especially vulnerable population during this unprecedented disaster because of the distress from the fearful experience itself, the disruption of prenatal care, nutritional alterations due to lack of electricity and fresh food supplies, and possible exposures to infectious and toxic materials. During the storm the majority of the 69 major hospitals on the island were left without electricity or fuel for their generators, and only three hospitals were functional 3–4 days after the storm2. Although obstetric services had to be available 24/7, not all women had access to them, and the conditions were far from adequate. The University Hospital was fully operational by day 8, and by day 9 it was estimated that the number of deliveries was 33% higher compared to the same month of the previous year2. The threat to life and multiple causes of a state of loss associated with this hurricane were a source of increased PNMS that can lead to significant maternal mental health problems like depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)2,6,7. Dietary changes are also a common consequence in these types of emergencies due to the lack of access to fresh food supplies8. The Island’s prevailing high importation rate added to the direct impact of the hurricane on the ports of entry further aggravated the loss of resources available to address basic needs.

Prenatal maternal stress due to natural disasters has been shown to impact practically all spheres of child development, including birth outcomes, and cognitive, motor, physical, socio-emotional, and behavioral development9,10. Previous experience from natural disasters like Hurricane Andrew (1992), Hurricane Katrina (2005), the Iowa Floods (2008), the Queensland Floods (2011) and the Ice Storm of Québec (1998) have shown that these types of prenatal stressors can lead to adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as prematurity, reduced birth weight and head circumference and other neonatal complications, especially in highly exposed women9,11,12,13,14. The long-term health consequences for the children who were prenatally exposed to these events are far more important, and they include effects on early infant temperament and motor development15, early cognitive development16, increased risk for immunologic conditions such asthma17 autism traits18,19 and obesity11.

Prenatal maternal stress may affect the fetus via the release of maternal stress hormones however, many of the long-term effects of prenatal maternal stress on offspring health can also be attributed to epigenetic changes to the fetal genome20,21. Children and adolescents prenatally exposed to the 1998 Québec Ice Storm showed significant differences in methylation levels of thousands of CpG sites, based on their mother’s objective prenatal maternal stress during the storm, and/or her cognitive appraisal of the impact of the storm in her life. The differentially methylated CpGs were affiliated with 1564 different genes and 408 biological pathways, primarily related to immune function22. These epigenetic changes were associated with significant health problems later in the life of these children, including obesity and diabetes23,24, and, more recently, brain development25.

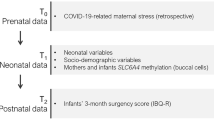

The objective of this study is to evaluate DNA methylation profiles in children who were exposed to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico during pregnancy in relation to hurricane-related maternal mental health exposures. Assessments were performed within two years of the exposure to the hurricane using validated measures for objective and subjective maternal stressors. Our hypothesis was that children who were prenatally exposed to maternal psychosocial and environmental stressors associated with Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico would have an altered DNA methylation profile. We report that the timing of the traumatic maternal event affects methylation patterns differently as expressed in early childhood. Specific measures of maternal stress are also associated with differing methylation patterns. The results of this study provide information for clinical providers working with women who experience a traumatic event during pregnancy. Our findings further inform the current understanding of the temporal dimension of DNA methylation during development by demonstrating differences in methylation levels based on the period of gestation at the time of the major traumatic event.

Results

A total of 47 significant differentially methylated single probes (DMPs) were associated with all hurricane-related variables tested (Supplemental Table 1).

We identified 30 significant DMPs associated with the gestation stage in weeks at the time of the hurricane (Fig. 1). Almost all DMPs significantly associated with the timing of the exposure are hypermethylated. The most significant hypermethylated probes cluster on chromosomes 1–4.

Mean methylation levels were calculated for each subject and used to explore the direction of methylation changes dependent on the time of maternal exposure to the hurricane. Maternal exposure between 20- and 25-weeks’ gestation yields higher mean methylation levels (Fig. 2). Average methylation values for women that were exposed in the first part of the third trimester (~ 30 weeks) are lower compared to other exposure times (Fig. 2).

One significant true differentially methylated region (DMR) with multiple probes was associated with the timing of the hurricane. This DMR contains four probes and is in the promoter region of LLRC39 gene. The FDR adjusted p-value for this region is 0.000355. The probes were in the 5′UTR and the TSS200 (within 200 base pairs of the transcription start site) region of the gene. The probes are in open chromatin. A heatmap of this region shows that higher methylation values are found in the children of women who were in the 2nd half (< 20 weeks) of their pregnancy during the hurricane impact (Supplementary Fig. S1). The LLRC39 gene produces a protein that is a component of the sarcomeric M-band, which plays a role in myocyte response to biomechanical stress26. Downregulation of LRRC39 in spontaneously beating engineered heart tissue results in a lower generation of force. An in-vivo zebrafish knockdown model of LRRC39 resulted in severely impaired cardiac function and cardiomyopathy26.

Of the 10 most significant DMPs associated with the timing of exposure, the most biologically relevant site is the probe located near the SPR (Sepiapterin Reductase) gene. This DMP is located within a CpG island and within 200 bps of the transcription start site in an open chromatin region. The enzyme sepiapterin reductase is involved in the production of the tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4), which converts amino acid precursors into the neurotransmitters serotonin and dopamine27. BH4 is also a necessary cofactor for nitric oxide (NO) synthesis via nitric oxide synthase (NOS). Mutations in this gene have been linked to hypertension and brachycardia, likely because of an imbalance between sympathetic and parasympathetic input and impaired NO production in endothelial cells28. SPR variants have also been linked to a higher susceptibility to bipolar disorder29 and an increased risk of schizophrenia in females of Han Chinese descent30. Other functions represented by genes associated with significant DMPs include basic cellular processes, apoptosis, and cell proliferation, and the epigenetic process of histone demethylation.

A total of five DMPs were associated with the constructed variable “prenatal maternal stress” (PNMS) (Supplementary Fig. S2). The high PNMS group included children of mothers with symptoms of moderate to severe depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), while the low PNMS mothers had no symptoms of depression or PTSD (Supplement: Study Sample). One of these DMPs is associated with the gene CRIP2; the same DMP is also significantly associated with the maternal PHQ-9 score. Another DMP significant in the PNMS group, associated with a region on chromosome 10, was also significant in the PTSD group. CRP2, the protein produced by the CRIP2 gene is associated with smooth muscle differentiation. CRP2 forms a complex with serum response factor and GATA proteins which converts fibroblasts to smooth muscle cells31.

Five significant DMPs were associated with the categorical PHQ-9 score, which measures levels of depression symptoms in the mothers (categories: none, mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe) were identified by the dmrff algorithm (Fig. 3). The significant DMPs map to genes involved in cell proliferation; protein folding, trafficking, prevention of aggregation, and proteolytic degradation; methionine metabolism/ histone methylation, and maintenance of intracellular calcium homeostasis. None of the significant DMPs for the PHQ-9 score are in a CpG-dense region or upstream of the transcription start site. Four of the five significant DMPs are hypermethylated and may represent a pattern of hypermethylation associated with this score.

Five significant DMPs were associated with the categorical PSS-10 score which measures symptoms of perceived maternal stress (categories: High, Moderate, Low) (Fig. 4). None of the significant DMPs are in a CpG dense region or upstream of the transcription start site. The significant DMPs map to genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism, actin cytoskeleton and cell polarity organization, and neuronal migration. Four of the five significant probes are hypermethylated and may represent a pattern of hypermethylation associated with this score.

Three significant DMPs were associated with the binary variable of presence/absence of PTSD symptoms (Supplementary Fig. S3). Of the three significant DMPs, two mapped to genes that are involved in RNA processing. Both DMPs were hypermethylated. One probe, associated with the HNRNPF gene is in a CpG island and in the TSS200 or 5′ UTR region depending on alternate splicing variants. The HNRNPF gene is part of the heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins [hnRNPs] family of genes that regulate mRNA processing and transport. The hnRNP family is also involved in regulating telomerase activity and telomere length32. Individuals with psychiatric disorders have significantly shorter telomeres33. Send et al.34 found higher levels of perceived maternal stress during pregnancy associated with shorter telomeres in newborns. Aberrant methylation of HNRNPF associated with maternal PTSD might represent an epigenetic pathway by which psychological maternal trauma is associated with shorter telomeres in offspring.

One significant DMP was associated with the categorical “property damage” score (Supplementary Fig. S4). It is located on chromosome 9, a CpG shore region, with an adjusted p-value of 0.013865217. This DMP is hypomethylated. The DMP is in the body of the JAK2 gene. The JAK2 protein is important for controlling the production of blood cells from hematopoietic stem cells and gain-of-function mutations have been linked to polycythemia vera and idiopathic erythrocytosis35.

Changes in global methylation at repetitive genomic elements have been linked with genomic instability and disease processes36. To explore if global methylation changes were associated with exposure to the hurricane, a linear model was applied to a subset of 17,730 probes associated with long interspersed nucleotide element-1 (LINE-1) elements. The PNMS variable (yes/no) was used to assess if there were methylation differences between the groups. No significant differences were found.

Discussion

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease theory (DOHaD) postulates that exposure to prenatal stressors during critical periods of early development could lead to permanent alterations of the developing tissues. These alterations could lead to a higher risk of developing serious pathological conditions later in life, such as obesity, cardiometabolic disease, immunological conditions, and mental health problems20. Although the biological mechanisms that mediate these effects are not completely understood, recent studies indicate that epigenetic mechanisms are an important “interface” through which the body interprets and responds to stressful experiences early in prenatal and perinatal life by modulating DNA function and gene expression21.

Founded on the principals of the DOHaD this study examined the impact of prenatal stress due to Hurricane Maria on the methylation profiles of children participating in the HELiOS cohort (Hurricane Exposures and Long-term Infant Outcomes Study), which includes 187 children exposed to hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico during pregnancy, and their mothers. The epigenetic analysis only included children who were evaluated within 2 years of the disaster, which is much earlier compared to previous studies on other natural disasters22,37. The timely evaluation of the mother–child dyads is a strength of this study because it allowed us to identify mothers who experienced higher levels of PNMS due to the disaster and to compare them against those with no apparent symptoms of mental distress. The assessments were performed using validated instruments, providing an additional strength to the study.

The timing of maternal exposure to the hurricane during pregnancy was the factor with the strongest impact on the methylation patterns in children. In the absence of a non-exposed control, this finding provides a strong argument that the observed effects were indeed related to the disaster. Property damage, another objective hurricane-related exposure, was associated with one significant DMP. Subjective measures of PNMS, such as maternal depression, stress, and PTSD symptoms were also associated with differences in methylation patterns in children in our study, but the impact was smaller. Previous studies in children prenatally exposed to the Quebec ice-storm in 1998 have also reported that the objective hardship experienced by the mothers during the natural disaster had a stronger association with the DNA methylation patterns of affected children, compared to more subjective maternal distress levels22. These observations reflect the difficulty in accurately quantifying maternal distress levels specifically related to the disaster, which could be due to the confounding effect of multiple other factors, including unrelated personal experiences and previous mental health history.

With respect to the timing of the hurricane, our data indicates that children whose mothers were exposed during the second half of their pregnancy had higher methylation values, in the promoter region of the LLRC39 gene, which is involved in the development of the sarcomeric M-band and may be associated with cardiac function. A recent study on adults who had been prenatally exposed to the Tangshan earthquake in 1976 also reported that those who had been exposed during the second trimester of pregnancy had significantly higher methylation levels in the promoter region of the human glucocorticoid gene NR3C1, and this finding was associated with poorer working memory performance37. Virk et al.38 found that the second trimester of pregnancy (13–27 weeks) was the most developmentally sensitive period for maternal bereavement, which acts through a similar pathway to stress, and this exposure was associated with higher risk for the development of type-2 diabetes later in life. Increased maternal cortisol levels during the second trimester of pregnancy have also been reported to be associated with decreased infant physical and neuromuscular maturation in males39.

HELiOS has collected extensive information on phenotypic characteristics of the children and potential confounders but we did not use these variables in the methylation analysis because of the small sample size. This may have biased our results, however, none of the mothers in the sample smoked either cigarettes or marijuana during pregnancy or heavily consumed alcohol. The small sample size is a limitation in this study, which decreased statistical power. To address this, we used the dmrff algorithm, which is more powerful than other comparable tools, to identify significant probes. The epigenetic findings of this study will guide our ongoing analysis evaluating the associations between the clinical outcomes and hurricane-related stressors within the entire HELiOS cohort, where we will include adjustments for confounders. Future studies are planned to evaluate the long-term clinical impact of hurricane Maria in the HELiOS cohort and to understand the underlying biological mechanisms that mediate the impact of early life stress on children’s health and development.

Methods

Study sample

Project HELiOS (Hurricane Exposures and Long-term Infant Outcomes Study) is a birth cohort that includes children who were prenatally exposed to Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico or were conceived within three months post-disaster (born 09/20/2017 and 09/21/2018) and their mothers. The HELiOS cohort consists of 187 maternal-child dyads. For this study, the research team selected 16 children of mothers with symptoms of moderate to high depression and PTSD [high PNMS group]. These were matched by age and gender to 16 children of mothers with no symptoms of depression or PTSD (low PNMS group). The final sample for this study consisted of 32 children, 26 males, and 6 females, aged between 13 to 23 months at the time of the study (average 17.1 ± 4.3 months). There is a small number of females in the sample. Differences in autosomal DNA methylation by sex have been found. A list of significant probe IDs from this study was compared to the list of probe IDs associated with biological sex found by Grant et al.40. There was no overlap. The age of the mothers at the time of the study was between 22 and 41 years (average 31.2 ± 4.8 years). Children born to mothers with history of depression and PTSD were not excluded as we used the presence of the current symptoms as a proxy of how much stress the mother had during the pregnancy. When considering the effects of maternal mental health status, current evidence suggests that it is irrelevant if the symptoms are related to a first episode of Major Depression Disorder (MDD)/PTSD or if it is a recurrence as post-disaster, as literature shows both increased incidence and recurrence of both disorders. The study was conducted following the ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects as defined by the declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol is approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus (UPR-MSC, Protocol #A0060118). Written consent approved by the IRB of the UPR-MSC was obtained by the mothers or legal guardians.

Study variables

Project HELiOS utilizes validated instruments to assess objective and subjective hurricane-related exposures, pregnancy outcomes, maternal and child medical histories, and child growth, development, and diet. In this report we included results for temporal, psychological, and selected hurricane exposure variables. Detailed pregnancy history, including pregnancy category and type of delivery was obtained using validated instruments currently used in other genetic cohort studies at the Dental and Craniofacial Genomics Core at the University of Puerto Rico. Gestational age (weeks) at the time of impact was used to assess the temporality of maternal exposure to the storm.

Maternal depressive symptoms were measured using the PHQ-9. The PHQ-9 is a multiple-choice, 4-point Likert scale, self-report inventory composed of nine items, assisting clinicians in screening for depression as well as selecting and monitoring treatment41. The PHQ-9 is a reliable and valid measure (α = 0.90) of depression severity42 and has been validated within primary care settings42,43. Its brevity makes it a useful clinical and research tool42 and it can detect and monitor depression in diverse ethnic/racial populations44. We have used scores of moderate depression or higher (score of 10 or higher) as indicator of depression. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) was used to assess subject maternal exposure to stress. The PSS-10 is widely used for measuring the degree in which situations in one’s life are perceived as stressful, unpredictable, and uncontrollable45. The PSS-10 was designed for at least a junior high school education. The questions are designed for any subpopulation group but have been previously used with pregnant women in post-hurricane settings46. The PSS-10 involves a 5-point Likert scale, with response ranging from 0 to 40, as higher scores indicate more stress. Scores from 0 to 13 are classified as low stress, 14–26 as moderate stress, and 27–40 as high stress. It has a good validity and reliability, with a α = 0.7644 and is used in Spanish in ongoing studies with Puerto Ricans. Post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms were measured using the PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), which is a 20-item self-report measure that assesses the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD 14. It takes approximately 5–10 min to complete. The total symptom severity score (range 0–80) is determined by summing the scores for each of the 20 items. We used the recommended cut-off for the PCL-5 of 33 points. We also used the criterion-based score (PCL-5 will be positive if the subject answers “moderately” or higher to all criteria needed for PTSD diagnosis). The PCL-5 has been translated into Spanish and has been used with Puerto Rican samples.

Measuring maternal mental health 1–2 years after Hurricane Maria is an ideal marker of PNMS as the moment of peak post-traumatic symptomatology is at this first-year mark47. Most cases of post-traumatic depression and PTSD improve over time, so the mothers that continue to present symptoms between 1 to 2 years after the hurricane are the more severe cases that will probably continue to present symptoms. Administration of certified psychological tests was performed by trained staff supervised by a licensed psychologist/psychiatrist from the Center for the Treatment and Management of Anxiety (CETMA) of the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus. Any mothers who exhibited symptoms requiring special mental health evaluation and treatment were referred to CETMA.

To assess objective prenatal exposures related to Hurricane Maria we adapted the Exposure to Disaster Scale48 that was used with Hispanic populations after Hurricane Andrew in Florida and Hurricane Georges49 in PR. This self-report questionnaire includes questions assessing the threat to life or danger encountered during the hurricane, any injury or illness to self or others and the degree of property damage or loss. The adaptation includes specific stressors for Hurricanes Irma and María captured through formal interviews with patients receiving treatment for PTSD at the CETMA. These adaptations include measuring how long the person lived without electricity and communication services and the effect of the hurricane on sleep patterns.

Blood samples were collected by trained nurses/phlebotomists at the Hispanic Alliance for Clinical and Translational Research (Alliance) of the UPR Medical Sciences Campus. Samples were immediately transported to the Alliance core laboratory facility for processing and storage by trained staff. Whole blood samples were aliquoted, snap-frozen in dry ice/ethanol and stored at -80 0C. Dried blood spot (DBS) samples were also prepared in filtered paper for future analysis of environmental exposures, in addition to metabolic and cortisol tests.

DNA methylation analysis

Coded blood samples were mailed to the Vieira Lab at the University of Pittsburgh for DNA methylation analysis. Samples were processed by the University of Pittsburgh Genomics Core. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was extracted from blood samples using the Qiagen DNeasy blood Mini Kit. Bisulfite modification of 1 µg DNA was conducted using an EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s procedure. The Infinium Methylation EPIC assay was performed according to Illumina’s standard protocol. Six sample pairs were processed on the same chip to account for chip-to-chip variation. All samples were run in duplicates. Infinium Methylation data was processed in R (version 4.0.2). Methylation levels of CpG sites were be calculated as β-values (β = intensity of the methylated allele (M)/ (intensity of the unmethylated allele (U) + intensity of the methylated allele (M) + 100)50. Data was preprocessed and analyzed according to the “A cross-package Bioconductor workflow for analyzing methylation array data”. All samples passed quality control (QC) with detection p-values > 0.05 and CpG coverage > 95% (Supplementary Fig. S5).

CpG sites (N = 11,648) on the sex chromosomes were not removed for the initial analysis. Data was normalized via the preprocess Funnorm function which performs better than other normalization methods on datasets with global methylation variation51. This function adjusts for known covariates via internal control probes, applies a background correction and corrects dye bias (Supplementary Fig. S6).

Probes with SNPs known to effect methylation at the probe site, or the single nucleotide extension were excluded. Cross-reactive probes were removed52. A cell heterogeneity correction was applied to normalized data53. To evaluate potentially confounding variables, MDS plots were created. Ethnicity and race affect methylation profiles54,55. In this dataset subjects did not cluster by race or ethnicity (Supplementary Fig. S7). The outliers in the MDS plots are samples with higher detection p-values.

Mode of delivery (Vaginal, C-section) may influence newborn methylation profiles, but the evidence is not conclusive56. In this dataset there is some clustering based on mode of delivery for subjects who delivered via un-scheduled C-section (Supplementary Fig. S8). This was used as a covariate in linear models to evaluate differential methylation. Preterm birth is also associated with differential methylation program in children57. In this dataset there was no clustering based on whether a delivery was term or preterm. A linear model was created via limma to assess the differential methylation by variable. All analyses were run using M-values, which have better statistical properties than beta values58. All tests were run using the false discovery rate (FDR) as a significance threshold59. To evaluate differential methylation the dmrff algorithm was used60. Like other popular methods of identifying differentially methylated sites, (bumphunter, comb-p, and DMRcate), dmrff uses EWAS summary statistics. Dmrff was chosen for this study because it combines these summary statistics from probes located in close proximity to each other. This takes into account that methylation marks at these sites is often interdependent, leading to is more power and better control of false positives than other tools. Data for DNase I hypersensitive sites (DHSs) is included for each significant site for which this data is available. DHSs indicate chromatin is not condensed at this location and is transcriptionally available.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Puerto Rico. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/PR.

Zorilla, C. The view from Puerto Rico—Hurricane Maria and its Aftermath|NEJM. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1713196.

Ferguson, K. K. et al. Demographic risk factors for adverse birth outcomes in Puerto Rico in the PROTECT cohort. PLoS ONE 14, e0217770 (2019).

Annual Report 2020. https://www.marchofdimes.org/annual-report-2020.

Rodríguez-Díaz, C. E. Maria in Puerto Rico: Natural disaster in a colonial archipelago. Am. J. Public Health 1971(108), 30–32 (2018).

Kishore, N. et al. Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 162–170 (2018).

Brock, R. L. et al. Peritraumatic distress mediates the effect of severity of disaster exposure on perinatal depression: The Iowa flood study: Peritraumatic distress and maternal mental health. J. Trauma. Stress 28, 515–522 (2015).

Dancause, K. N. et al. Dietary change mediates relationships between stress during pregnancy and infant head circumference measures: The QF2011 study. Matern. Child Nutr. 13, (2017).

Lafortune, S. et al. Effect of natural disaster-related prenatal maternal stress on child development and health: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18, (2021).

Beversdorf, D. Q., Stevens, H. E., Margolis, K. G. & Van de Water, J. Prenatal stress and maternal immune dysregulation in autism spectrum disorders: Potential points for intervention. Curr. Pharm. Des. 25, 4331–4343 (2019).

Kroska, E. B. et al. The impact of maternal flood-related stress and social support on offspring weight in early childhood. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 21, 225–233 (2018).

Xiong, X. et al. Exposure to Hurricane Katrina, post-traumatic stress disorder and birth outcomes. Am. J. Med. Sci. 336, 111–115 (2008).

Harville, E. W., Giarratano, G., Savage, J., Barcelona de Mendoza, V. & Zotkiewicz, T. Birth outcomes in a disaster recovery environment: New Orleans women after Katrina. Matern. Child Health J. 19, 2512–2522 (2015).

Norris, F. H., Foster, J. D. & Weisshaar, D. L. The epidemiology of gender differences in PTSD across developmental, societal, and research contexts. In Gender and PTSD. 3–42 (The Guilford Press, 2002).

Tees, M. T. et al. Hurricane Katrina-related maternal stress, maternal mental health, and early infant temperament. Matern. Child Health J. 14, 511–518 (2010).

Laplante, D. P., Hart, K. J., O’Hara, M. W., Brunet, A. & King, S. Prenatal maternal stress is associated with toddler cognitive functioning: The Iowa Flood Study. Early Hum. Dev. 116, 84–92 (2018).

Turcotte-Tremblay, A.-M. et al. Prenatal maternal stress predicts childhood asthma in girls: Project ice storm. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 201717–201810 (2014).

Walder, D. J. et al. Prenatal maternal stress predicts autism traits in 6½ year-old children: Project Ice Storm. Psychiatry Res. 219, 353–360 (2014).

Kinney, D. K., Miller, A. M., Crowley, D. J., Huang, E. & Gerber, E. Autism prevalence following prenatal exposure to hurricanes and tropical storms in Louisiana. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 38, 481–488 (2008).

Heindel, J. J., Skalla, L. A., Joubert, B. R., Dilworth, C. H. & Gray, K. A. Review of developmental origins of health and disease publications in environmental epidemiology. Reprod. Toxicol. 68, 34–48 (2017).

Vineis, P. et al. Epigenetic memory in response to environmental stressors. FASEB J. 31, 2241–2251 (2017).

Cao-Lei, L. et al. DNA methylation signatures triggered by prenatal maternal stress exposure to a natural disaster: Project Ice Storm. PLoS ONE 9, e107653 (2014).

Cao-Lei, L. et al. DNA methylation mediates the effect of maternal cognitive appraisal of a disaster in pregnancy on the child’s C-peptide secretion in adolescence: Project Ice Storm. PLoS ONE 13, e0192199–e0192199 (2018).

Cao-Lei, L. et al. Pregnant women’s cognitive appraisal of a natural disaster affects DNA methylation in their children 13 years later: Project Ice Storm. Transl. Psychiatry 5, e515–e515 (2015).

Cao-Lei, L. et al. Prenatal maternal stress from a natural disaster and hippocampal volumes: Gene-by-environment interactions in young adolescents from project ice storm. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 15, 706660 (2021).

Will, R. D. et al. Myomasp/LRRC39, a heart- and muscle-specific protein, is a novel component of the sarcomeric M-band and is involved in stretch sensing. Circ. Res. 107, 1253–1264 (2010).

Bonafé, L., Thöny, B., Penzien, J. M., Czarnecki, B. & Blau, N. Mutations in the sepiapterin reductase gene cause a novel tetrahydrobiopterin-dependent monoamine-neurotransmitter deficiency without hyperphenylalaninemia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 269–277 (2001).

Sumi-Ichinose, C. et al. Sepiapterin reductase gene-disrupted mice suffer from hypertension with fluctuation and bradycardia. Physiol. Rep. 5, e13196 (2017).

McHugh, P. C., Joyce, P. R. & Kennedy, M. A. Polymorphisms of sepiapterin reductase gene alter promoter activity and may influence risk of bipolar disorder. Pharmacogenet. Genom. 19, (2009).

Fu, J. et al. Association study of sepiapterin reductase gene promoter polymorphisms with schizophrenia in a Han Chinese population. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 11, 2793–2799 (2015).

Chang, D. F. et al. Cysteine-rich LIM-only proteins CRP1 and CRP2 are potent smooth muscle differentiation cofactors. Dev. Cell 4, 107–118 (2003).

Shishkin, S. S., Kovalev, L. I., Pashintseva, N. V., Kovaleva, M. A. & Lisitskaya, K. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins involved in the functioning of telomeres in malignant cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 745 (2019).

Darrow, S. M. et al. The association between psychiatric disorders and telomere length: A meta-analysis involving 14,827 persons. Psychosom. Med. 78, 776–787 (2016).

Send, T. S. et al. Telomere length in newborns is related to maternal stress during pregnancy. Neuropsychopharmacology 42, 2407–2413 (2017).

Akada, H., Akada, S. & Mohi, G. Critical role of Jak2 in the maintenance and function of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Blood 122, 1180–1180 (2013).

Pappalardo, X. G. & Barra, V. Losing DNA methylation at repetitive elements and breaking bad. Epigenet. Chromatin 14, 25 (2021).

Wang, R. et al. Prenatal earthquake stress exposure in different gestational trimesters is associated with methylation changes in the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) and long-term working memory in adulthood. Transl. Psychiatry 12, 1–7 (2022).

Virk, J. et al. Prenatal exposure to bereavement and type-2 diabetes: A Danish longitudinal population based study. PLoS ONE 7, e43508–e43508 (2012).

Ellman, L. M. et al. Timing of fetal exposure to stress hormones: Effects on newborn physical and neuromuscular maturation. Dev. Psychobiol. 50, 232–241 (2008).

Grant, O. A., Wang, Y., Kumari, M., Zabet, N. R. & Schalkwyk, L. Characterising sex differences of autosomal DNA methylation in whole blood using the Illumina EPIC array. Clin. Epigenet. 14, 62 (2022).

phqscreeners. https://www.phqscreeners.com/index.html.

Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L. & Williams, J. B. W. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613 (2001).

Litster, B. et al. Validation of the PHQ-9 for suicidal ideation in persons with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 24, 1641–1648 (2018).

Kroenke, K. et al. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 114, 163–173 (2008).

Cohen, S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In The Social Psychology of Health. 31–67 (Sage Publications, Inc, 1988).

Solivan, A. E., Xiong, X., Harville, E. W. & Buekens, P. Measurement of perceived stress among pregnant women: A comparison of two different instruments. Matern. Child Health J. 19, 1910–1915 (2015).

Bravo, M., Rubio-Stipec, M., Canino, G. J., Woodbury, M. A. & Ribera, J. C. The psychological sequelae of disaster stress prospectively and retrospectively evaluated. Am. J. Community Psychol. 18, 661–680 (1990).

Norris, F. H., Perilla, J. L., Riad, J. K., Kaniasty, K. & Lavizzo, E. A. Stability and change in stress, resources, and psychological distress following natural disaster: Findings from hurricane Andrew. Null 12, 363–396 (1999).

Felix, E. et al. Natural disaster and risk of psychiatric disorders in Puerto Rican children. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 39, 589–600 (2011).

Bibikova, M. et al. High density DNA methylation array with single CpG site resolution. Genomics 98, 288–295 (2011).

Fortin, J.-P. et al. Functional normalization of 450k methylation array data improves replication in large cancer studies. Genome Biol. 15, 503 (2014).

Chen, Y. et al. Discovery of cross-reactive probes and polymorphic CpGs in the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450 microarray. Epigenetics 8, 203–209 (2013).

Houseman, E. A. et al. Reference-free deconvolution of DNA methylation data and mediation by cell composition effects. BMC Bioinform. 17, 259 (2016).

Adkins, R. M., Krushkal, J., Tylavsky, F. A. & Thomas, F. Racial differences in gene-specific DNA methylation levels are present at birth. Birth Defects Res. A 91, 728–736 (2011).

Xia, Y. et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in human DNA methylation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Rev. Cancer 1846, 258–262 (2014).

Chen, Q. et al. The impact of cesarean delivery on infant DNA methylation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 265 (2021).

Lester, B. M. et al. Neurobehavior related to epigenetic differences in preterm infants. Epigenomics 7, 1123–1136 (2015).

Du, P. et al. Comparison of Beta-value and M-value methods for quantifying methylation levels by microarray analysis. BMC Bioinform. 11, 587 (2010).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 57, 289–300 (1995).

Suderman, M. et al. dmrff: Identifying differentially methylated regions efficiently with power and control. bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/508556 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health grants R21MD013652 (EMB, CBM, KMG); Hispanic Alliance for Clinical and Translational Research (U54GM133807, EMB). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We thank all the participants that contributed to this study and shared their stories regarding the landfall and the aftermath of Hurricane Maria. We would like to acknowledge the staff and students of the HELiOS project team at the Dental and Craniofacial Genomics Core, the Oral Biology Laboratory, the Center for the Treatment of Fear and Anxiety (CETMA) and the Hispanic Alliance for Clinical and Translational Research at the University of Puerto Rico Medical Sciences Campus for their work with the recruitment of the participants, and the collection of clinical data and samples. We wish to thank Kathleen Deeley of the Vieira lab for assisting with the lab work for this project and Dongjing Liu of The University of Pittsburgh Department of Human Genetics for assisting with data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: E.M.B., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., A.R.V. Methodology: A.R.V., E.K., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., E.M.B., S.R.T. Formal analysis: A.R.V., E.K. Investigation: A.R.V., E.K., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., E.M.B., S.R.T., M.C.R. Visualization: A.R.V., E.K. Funding acquisition: E.M.B., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., A.R.V. Project administration: E.M.B., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., A.R.V. Supervision: E.M.B., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B., A.R.V. Writing—original draft: A.R.V., E.K., E.M.B., K.G.M.-G., C.J.B. Writing—review and editing: S.R.T., M.C.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kello, E., Vieira, A.R., Rivas-Tumanyan, S. et al. Pre- and peri-natal hurricane exposure alters DNA methylation patterns in children. Sci Rep 13, 3875 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30645-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30645-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.