Abstract

In this article we assessed the prevalence of benzodiazepine (BZD) use in women before and during imprisonment, as well as its related factors and association with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder in a quantitative, cross-sectional, analytical study of regional scope. Two female prisons in the Brazilian Prison System were included. Seventy-four women participated by completing questionnaires about their sociodemographic data, BZD use and use of other substances. These questionnaires included the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7), Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL-C). Of the 46 women who reported no BZDs use before arrest, 29 (63%) began using BZDs during imprisonment (p < 0.001). Positive scores for PTSD, anxiety, and depression, as well as associations between BZD use during imprisonment and anxiety (p = 0.028), depression (p = 0.001) and comorbid anxiety and depression (p = 0.003) were found when a bivariate Poisson regression was performed. When a multivariate Poisson regression was performed for tobacco use, the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales, BZD use was associated with depression (p = p = 0.008), with tobacco use (p = 0.012), but not with anxiety (p = 0.325). Imprisonment increases the psychological suffering of women, consequently increasing BZD use. Nonpharmacological measures need to be considered in the health care of incarcerated women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are usually indicated during the treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, muscle spasms, and seizures1,2,3. BZDs are among the most prescribed drugs, with the number of prescriptions increasing in the last two decades4. In the USA, prescriptions for BZDs have increased threefold or more in the last decade, particularly for long-term users4,5,6. The rates of BZD use are 5.2% of adults in the US2, 4% in Canada7, and 7.5% in France8. In the Brazilian general population, 3.6% of individuals use BZDs, and 7.8% of individuals have mental health problems9. However, little information on prevalence rates and patterns of BZD use in female prisoners is available in the literature10.

Hassan et al.11 discuss the surprisingly high prevalence of prescribed psychotropic drugs, including BZDs, for female prisoners compared to that of male prisoners and women in the general population. These authors found a higher prevalence of hypnotic and anxiolytic prescriptions for female prisoners (with diazepam prescriptions comprising 50% of prescriptions). The prevalence of prescriptions was 7.9% in female prisoners but 1.0% in male prisoners and 2.5% in the general female population. For female prisoners, 85.7% of these prescriptions represent a valid indication of these drugs and 98.3% represent a valid dose11.

A worrying emerging reality is the significant increase in female incarceration rates internationally12. In Brazil, the general incarceration rate increased by more than 150% between 2000 and 2017, which calls for increased attention of researchers and suggests the need for more research in prisons13,14.

An important problem identified in female prisoners is the prevalence of psychiatric disorders15,16. Incarcerated women show higher prevalences of most illnesses, especially depressive disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders17.

In addition to psychiatric disorders, there has been an increase in drug use disorders in prisons during the last three decades18. Two-thirds of sentenced prisoners (63%) meet criteria for addiction or abuse of marijuana/hashish, cocaine/crack, heroin/opiates, depressants, stimulants, methamphetamines, hallucinogens and inhalants19. Higher rates of lifetime substance use disorder are found in female prisoners than in females in the general population (25.2% vs. 1.6%)20. An Irish study found a 17.2% rate of alcohol use disorder and 62.6% rate of substance use disorder21 in a female prison population.

In this study we aim to verify the prevalence of BZD use and other substance use in incarcerated women before and during imprisonment as well as the association of BZD use with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Methods

Study design

This study is quantitative, cross-sectional, and analytical, with regional coverage. It is a secondary analysis of data from the PPSUS Project, “Incarcerated women: Context of violence and needs arising from drug use”, EFP_0001396822. After an initial analysis of the data, our attention was drawn to the significant increase in BZD use by women during incarceration, which motivated the present study.

Study population and inclusion criteria

The population consisted of women from the Prison System of Porto Alegre and the Metropolitan Region of Porto Alegre. Two prisons were selected that had a basic health unit and comprised a total of 502 women, in 201923. Seventy-four women over 18 years old who had served a sentence for at least 6 months in closed conditions were randomly selected. The women who agreed to participate in the research signed an informed consent form.

Data collection methods

The researchers participating in the data collection were trained so that they could administer the questionnaires in the same way. For the data collection, self-assisted tablet interviews were conducted through an offline system, Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap)23, using a structured questionnaire with closed questions about sociodemographic characteristics, information about time and cause of incarceration, use of BZD and other drugs (tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, snorted cocaine, crack) and mental health. These questions were taken from the following validated scales: the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist–Civilian Version (PCL-C)24, the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)25, and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale-7 (GAD-7)26.

BZDs were the substance of interest in this study, as they are a subclass of one of the ten classes of drugs related to relevant disorders, according to the DSM-527 Self-reported data on BZD use including the frequency of use and whether the use was under prescription were collected for two time points: describing use before being arrested and in the last 6 months after their arrest. For the frequency of use, responses were grouped into the following categories and subcategories: more than once per week (every day and more than once a week), from once a week to occasional use in 6 months (once a week to more than once every 6 months), and approximately once in 12 months (once every 6 months, more than once a year, once a year, once in a lifetime). Nondichotomous variables were grouped into categories of race (White or Caucasian and other races, including Asian, Hispanic or South Asian, Black (quilombola), and Black (nonquilombola); level of schooling (less than 8 years of schooling and secondary/higher education) and marital status (single, which included single and separated/divorced/widowed women, and married, which included women who were married, in a stable relationship or with a steady partner). Two time points, before and during imprisonment (the 6 month period following arrest), were considered during data collection on the type of drug used (tobacco, alcohol, marijuana, cocaine snorted, crack) and frequency of use. The mental health assessment of female prisoners considered the period of 6 months after imprisonment. The questionnaires used were the (PCL-C with a cutoff of 5024; the PHQ-9 with a cutoff of 1025; and the GAD-7 with a cutoff of 1026. The scores were considered “Negative” or “Positive” based on the cutoff values.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were completed using SPSS, version 20.0. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was adopted. The prevalence for the study’s categorical variables was determined. To describe the age variable, the mean and standard deviation were used. A multicollinearity test was performed between the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 to certify that there would be no overlapping variables compromising the results. To assess the change in BZD use and other substances before and during imprisonment, the McNemar chi-square test was used. To assess the change in the frequency of use, the McNemar-Bowker chi-square test was used. A simple robust Poisson regression was performed to assess the association of different risk factors with BZD use (95% confidence interval). After this analysis, variables with p < 0.20 (PHQ-9, GAD-7, tobacco use with BZD use) were included in the multivariate Poisson regression28.

To compare the overall use of BZDs in female prisoners before and during imprisonment, discordant pairs were used (39.2% of those who did not use BZDs before and started using BZDs during imprisonment and 5.4% who used BZDs before and stopped using BZDs during imprisonment), with a power of 99%.

Ethics declarations

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The present study was approved by the Ethics in Health Research Committee of the Psychology Institute of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) (#2.832.322).

Results

The following characteristics of the studied population were found: predominance of young inmates, with a mean age of 37.8 to 38.9 years among nonusers and users of BZDs; 43 (58.1%) White or Caucasian women and 31 (41.9%) women of other races (Asian, Black (quilombola), and Black (nonquilombola). Regarding education, 53 (71.6%) women achieved less than 8 years of study, and 21 of them (28.4%) had completed high school or pursued a university degree (complete or incomplete). Fifty (67.6%) women were married (including those with a stable union or steady partner), while 24 (32.4%) reported being single, separated, divorced or widowed. Sixty-six (89.2%) reported being mothers, and 8 (10.8%) did not have children. Forty-five women (60.8%) reported that they were responsible for family income, and 28 (37.8%) reported that they were not.

At the time of data collection, the prison time interval of the women participating in this research was 7 months to 138 months, with an average prison time of 32.65 months. According to the criminal classification, 32 women (43.2%) were arrested for crimes related to drugs, 21 (28.4%) for crimes against people, 1 (1.4%) for crimes related to weapons, 10 (13, 5%) for crimes against sexual dignity and 12 (16.2%) women were arrested for crimes against property.

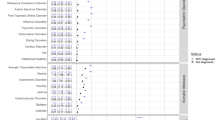

There was a relationship between tobacco use and BZD use. An association between BZD use and sociodemographic variables was not found in prison (Table 1).

Of the 74 women inmates, 28 (38%) women used BZDs, and 46 (62%) women did not use BZDs before imprisonment. Of the women who used BZDs before imprisonment, 24 (32.4%) continued using BZDs, and 4 (5.4%) stopped using BZDs during imprisonment. Of the 46 (62%) women who did not use BZDs before prison, 17 (23%) continued to not use BZDs, while 29 (39.2%) started using BZDs during imprisonment. Of the 46 women who did not use BZDs, a significant proportion 29 (63%) started to use BZDs (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1).

The participants showed a substantial increase in their frequency of BZD use. Before imprisonment, 20 women (27%) reported frequent use of BZDs (more than once a week), while 46 (62.2%) women reported not using BZDs. During imprisonment, 21 (28.4%) of the 46 women who had not used BZDs continued to not use BZDs, but a significant proportion of them, 25 (54%), started using BZDs very frequently (more than once a week), with a p value < 0.001. The 48 (64.9%) women who used BZDs more than once a week during imprisonment comprised the women who used BZDs more than once a week before imprisonment (n = 20; 27%) + women who did not use BZDs before imprisonment and started to use BZDs during imprisonment (n = 25; 33.7%) + the number of women who used BZDs before imprisonment at a frequency of once a week to occasional use in 6 months (n = 3; 4.2%) (Fig. 2).

We also quantified prevalence rates for the current use of tobacco (64.9%), marijuana (10.9%), snorted cocaine (8.2%), crack (4.1%) and alcohol (1.4%). A statistically significant decrease in the use of alcohol, marijuana, snorted cocaine and crack was observed when comparing current use during incarceration (including women who previously used these substances and continued to use them in prison and those who did not previously use them and started to use them during incarceration) with previous use (Table 2).

Considering the similar effects on the central nervous system (CNS) of BZDs and alcohol (a CNS depressant agent)27, we analyzed the use of alcohol before incarceration and the current use of BZDs. The results did not show a statistically significant different in alcoholic beverage use before and BZD use after (p = 0.637).

The rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety based on the mental health questionnaires used in this study are shown in Table 3. More than 80% of the women who had “positive” scores for PTSD, anxiety and depression reported use of BZDs. In the Poisson regression analysis of the mental health assessment scales (GAD-7, PHQ-9, and PTSD) and BZD use, it was found that of the 22 women with PTSD (positive PCL-C classification), 18 women (81.8%) were using BZDs; however, there was no statistically significant relationship between PCL-C classification and BZD use (p = 0.161). Regarding the GAD-7, of the 45 women who had anxiety based on a positive GAD-7 classification, 37 (82.2%) reported using BZDs during incarceration with p = 0.028, indicating a significant relationship between GAD-7 classification and BZD use. When analyzing the PHQ-9 scale, a total of 33 participants had depression based on a positive PHQ-9 classification, of which 30 (90.9%) used BZDs with p = 0.001. A significant relationship was found (p = 0.003) for women who had comorbid anxiety and depression and reported using BZDs (Table 3).

Before incarceration, 100% of BZD use was prescribed. During imprisonment, the rate of BZDs used that was prescribed dropped to 88.7%; 6 women (11.3%) self-reported the use of BZDs without a prescription.

When a multivariate Poisson regression was performed with BZD use, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scales, and tobacco use, BZD use was associated with the PHQ-9 scale (p = 0.008), and tobacco use (p = 0.012), but not the GAD-7 (p = 0.325) (Table 4).

Discussion

The main results are as follows: (a) the prevalence of BZD use by women more than doubles in the first months of incarceration; (b) BZDs are used more frequently during imprisonment than before imprisonment; (c) Positive scores for PTSD, anxiety, and depression had high prevalence rates; (d) There is an association between BZD use by women in prison with anxiety, depression and comorbid anxiety and depression; (e) Women who use BZDs have a statistically significant likelihood of having a positive score for depression but not for anxiety; (f) tobacco use increased during incarceration and the use of other substances decreased; (g) no association was found between BZD use in prison and alcohol use before prison.

Most data on sociodemographic characteristics are in accordance with the population of incarcerated women in Brazil29; these women are quite young, have a low educational attainment, are not married and are mothers of one or more children. The main difference is that there is a predominance of White women included in the current study, while in the Brazilian female prison population, 48.04% are mixed-race and 15.51% are black. The three southern Brazilian states have a greater number of incarcerated White women, with 63% of the incarcerated population being White or Caucasian30, which follows the general profile of the population of Rio Grande do Sul that is related to immigration waves from the nineteenth century that predominantly included European immigrants31. Considering that almost 90% of these women were mothers, it is noteworthy that the interruption of close relationships, especially separation from children and abandonment by friends, are factors that worsen mental suffering in female prisoners32,33. The breakdown of the family unit after imprisonment has worse consequences for women than men32.

This study found an increase in the prevalence and frequency of BZD use in women during imprisonment. It is recognized that nonincarcerated women have high rates of BZD use2,4,27,34,35, and the increase in BZD use, both in prevalence and in frequency of use by women during imprisonment, might be related to stressors and anxiogenic factors related to incarceration itself33,36. Most prisons are adapted spaces36 that are uncomfortable, overcrowded, noisy, and busy, with poor infrastructure and sanitary conditions10,33,37,38. Women report feelings of degradation, humiliation and objectification36, with consequent changes in their self-conception32. Sadness, loneliness, abandonment, anger, idleness, anxiety, stress, depression, and changes in sleep patterns are factors that affect the mental health of women in this context33.

In addition to their calming function, BZDs provide a feeling of disconnection or escape from reality and a change in temporal perception (with BZDs, time seems to pass faster), motivating incarcerated women to use them33,36,39. The reported increase in use and frequency of use in the first months during imprisonment needs to be thoroughly considered in addition to guidelines for BZD prescription and the risk of misuse40.

A high prevalence of mental health conditions was found here, as in other studies in the international literature12,32,33,41,42,43. The mental health of women in prison is more affected than their physical health due to factors that are socially inherent to the gender, namely, responsibility for their families in combination with isolation and lack of social support32. Here, we show that approximately one-third of female inmates presented with PTSD, similar to other studies44, reflecting the extent to which incarceration per se and its consequences are traumatic. Previous studies have shown that female inmates have higher prevalence rates of mental health conditions than male inmates44, and there are significant associations between PTSD and other disorders (depression, anxiety, and substance use)45. The prevalence of depression among inmates of both sexes is approximately 40%46, but it is almost 50% among older female inmates47. The rate of depression in older female inmates is similar to the rate observed here, although this group is composed of younger women. One-third of the inmates interviewed reported anxiety and depression. In prisons, anxiety prevalence rates range between 19.138 and 43% in older female inmates47, which are much lower than the rates observed here, with 60.8% of the inmates having a positive GAD-7 classification. The potentially traumatizing environment of prison12 does not provide the emotional or psychological support these women need. BZD use could be avoided if evidence-based psychological care were properly offered.

In Spain, in addition to symptoms related to anxiety and depression, consumption of alcohol and other drugs is frequent in female inmates48. An American report found higher rates of substance use in female prisoners (47%) than in male prisoners (38%)19. Incarcerated women have a 20% rate of alcohol use disorders and a higher, 51%, prevalence rate of illicit drug use disorders18. Much lower prevalences were found in our study, especially for the use of alcohol and other drugs. This result seems to be more related to the control system in Brazilian prisons, which limits access to drugs, than to effective care responses for these women. An estimate of the prevalence of nicotine use during imprisonment in low- and middle-income countries ranged from 5 to 87%, with an overall estimate of 56%16. A Swiss study found 78.3% rates of women smoking in prison49. The high prevalence of smoking in prison found in our study (65%) and in the international literature suggests that smoking-related policies need careful review. Our study did not find a relationship between alcohol use before imprisonment and BZD use during imprisonment, although pharmacological treatment with BZDs represents the gold standard for alcohol withdrawal syndrome treatment50.

One of the limitations of this study is the relatively small number of participants, emphasizing the need to expand the studied population. It is possible that a considerable number of women at high risk of BZD misuse or abuse did not participate in the survey, which may have led to underestimation of the prevalence of BZD use. The results of this research were obtained from a sample of women in two prisons in the southern region of Brazil and should be applied with caution in other locations. Brazilian female prisons may differ in their structure from prisons in other locations. The absence of data on the use of other psychotropic medications is another limitation of this study. Another aspect is that the prevalence of BZD use and frequency of use was based on self-reported responses, which may introduce a memory bias.

Conclusion

This study emphasizes the urgency of discussing the precise indication and rational BZD use in women in prison. Current guidelines indicate the risks of inadvertently prescribing BZDs. This reinforces the importance of structuring strategies for the rationalization of use, ranging from indications based on scientific evidence to the prioritization of nonpharmacological interventions for the treatment of female inmates.

Prison environments and women’s mental health needs are complex. Female inmates require care that begins with specific knowledge of women and their vulnerabilities. This study confirms the importance of interdisciplinary research that includes different perspectives for the structuring of public health policies.

It is noteworthy that researching BZD use in incarcerated women reinforces the importance of study designs that address phenomena as they happen in real life. It is expected that these results will help in the structuring of public health policies aimed at women in prison. The understanding of the prevalence of mental suffering and the increase in the use and frequency of BZDs and tobacco found in this study may ultimately contribute to the construction of effective surveillance and monitoring strategies for this population, to the organization of the provision of services and to the recognition of the need for the incorporation of interdisciplinary therapeutic resources in the treatment of PTSD, anxiety, and depression in prisons.

Data availability

Women prisoners constitute a vulnerable population. Requests for materials and data relating to this study should be addressed to F.M.S.E.

References

López-Muñoz, F., Álamo, C. & García-García, P. The discovery of chlordiazepoxide and the clinical introduction of benzodiazepines: Half a century of anxiolytic drugs. J. Anxiety Disord. 25, 554–562 (2011).

Olfson, M., King, M. & Schoenbaum, M. Benzodiazepine use in the United States. JAMA Psychiat. 72, 136 (2015).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP20–07–01–001, NSDUH Series H-55). https://store.samhsa.gov/ (2020).

Agarwal, S. D. & Landon, B. E. Patterns in outpatient benzodiazepine prescribing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2, e187399 (2019).

Bachhuber, M. A., Hennessy, S., Cunningham, C. O. & Starrels, J. L. Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the United States, 1996–2013. Am. J. Public Health 106, 686–688 (2016).

Johansen, M. E. & Niforatos, J. D. Benzodiazepine use in the USA is driven by long-term users: A repeated cross-sectional study of MEPS 2002–2016. J. Gen. Intern. Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05042-2 (2019).

Moore, N., Pariente, A. & Bégaud, B. Why are benzodiazepines not yet controlled substances?. JAMA Psychiat. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2190 (2015).

Lagnaoui, R. et al. Patterns and correlates of benzodiazepine use in the French general population. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-004-0808-2 (2004).

Campanha, A. M. et al. Benzodiazepine use in Sao Paulo, Brazil. Clinics 75, (2020).

van Hout, M. C. & Mhlanga-Gunda, R. Contemporary women prisoners health experiences, unique prison health care needs and health care outcomes in sub Saharan Africa: A scoping review of extant literature. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 18, 31 (2018).

Hassan, L. et al. Prevalence and appropriateness of psychotropic medication prescribing in a nationally representative cross-sectional survey of male and female prisoners in England. BMC Psychiatry 16, 1–10 (2016).

Bartlett, A. & Hollins, S. Challenges and mental health needs of women in prison. Br. J. Psychiatry 212, 134–136 (2018).

Brasil. Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias: Atualização - Junho 2017. Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública http://depen.gov.br (2019).

Brasil. Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Projeto BRA 34/2018: Produto 5 Relatório Temático Sobre as Mulheres Privadas de Liberdade, Considerando os Dados do Produto 01,02, 03 e 04. (2019).

Baranyi, G. et al. Severe mental illness and substance use disorders in prisoners in low-income and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence studies. Lancet Glob. Health 7, e461–e471 (2019).

Mundt, A. P., Baranyi, G., Gabrysch, C. & Fazel, S. Substance use during imprisonment in low-and middle-income countries. Epidemiol. Rev. 40, 70–81 (2018).

Karlsson, M. E. & Zielinski, M. J. Sexual victimization and mental illness prevalence rates among incarcerated women: A literature review. Trauma Violence Abuse https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018767933 (2020).

Fazel, S., Yoon, I. A. & Hayes, A. J. Substance use disorders in prisoners: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis in recently incarcerated men and women. Addiction https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13877 (2017).

Bronson, J., Stroop, J., Zimmer, S. & Berzofsky, M. Drug use, dependence, and abuse among state prisoners and jail inmates, 2007–2009. US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics (2017).

Andreoli, S. B. et al. Prevalence of mental disorders among prisoners in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil. PLoS ONE 9, e88836 (2014).

Gulati, G. et al. The prevalence of major mental illness, substance misuse and homelessness in Irish prisoners: Systematic review and meta-analyses. Ir. J. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/ipm.2018.15 (2019).

Dias, M. T. G. Mulheres privadas de liberdade: Contexto de violências e necessidades decorrentes do uso de drogas. 1–5 Preprint at (2017).

Dias, M. T. G. Banco de Dados da Pesquisa Mulheres privadas de liberdade: Contexto de violências e necessidade decorrentes do uso de drogas, desenvolvido pelo sistema REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). Preprint at (2019).

Berger, W., Mendlowicz, M. V., Souza, W. F. & Figueira, I. Equivalência semântica da versão em português da Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist - Civilian Version (PCL-C) para rastreamento do transtorno de estresse pós-traumático. Rev. Psiquiatr. Rio Grande do Sul 26, 167–175 (2004).

Santos, I. S. et al. Sensibilidade e especificidade do Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) entre adultos da população geral. Cad Saude Publica 29, 1533–1543 (2013).

Bártolo, A., Monteiro, S. & Pereira, A. Factor structure and construct validity of the generalized anxiety disorder 7-item (GAD-7) among Portuguese college students. Cad Saude Publica 33, 1–12 (2017).

American Psychiatric Association. Manual diagnóstico e estatístico de transtornos mentais - DSM-5, estatísticas e ciências humanas: inflexões sobre normalizações e normatizações. Rev. Int. Interdiscip. INTERthesis 11, 96 (2014).

Barros, A. J. & Hirakata, V. N. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: An empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 3, 21 (2003).

Brasil. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Levantamento Nacional de Informações Penitenciárias: dezembro de 2019. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiMmU4ODAwNTAtY2IyMS00OWJiLWE3ZTgtZGNjY2ZhNTYzZDliIiwidCI6ImViMDkwNDIwLTQ0NGMtNDNmNy05MWYyLTRiOGRhNmJmZThlMSJ9 (2020).

Brasil. Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Departamento Penitenciário Nacional. Projeto BRA 34/2018: produto 5 relatórios temáticos sobre as mulheres privadas de liberdade, considerando os dados do produto 01,02,03 e 04. https://www.gov.br/depen/pt-br/sisdepen/mais-informacoes/relatorios-infopen/relatorios-sinteticos/infopenmulheres-junho2017.pdf (2019).

de Santos, M. O. Reescrevendo a história: Imigrantes italianos, colonos alemães, portugueses e a população brasileira no sul do Brasil. Rev. Tempo Argumento 09, 230–246 (2017).

de Lima, G. M. B., de Neto, A. F. P., de Amarante, P. D. C., Dias, M. D. & de Ferreira Filha, M. O. Mulheres no cárcere: Significados e práticas cotidianas de enfrentamento com ênfase na resiliência/Women in prison: Meanings and everyday practices of coping with emphasis on resilience. Saúde Debate 37, 446–456 (2013).

dos Santos, M. V. et al. Mental health of incarcerated women in the state of Rio de Janeiro. Texto Contexto Enferm. 26, 1–10 (2017).

Bezerra, D. S., Bonzi, A. R. B., da Silva, G. R. & da Lima, A. K. B. S. Mulheres eo uso de benzodiazepínicos: Uma revisão integrativa. Temas Saúde 18, 204–215 (2018).

Brett, J. et al. Benzodiazepine use in older adults in the United States, Ontario, and Australia from 2010 to 2016. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 66, 1180–1185 (2018).

Vildoso-Cabrera, E., Navas, C., Vildoso-Picón, L., Larrea, L. & Cabrera, Y. Prison infrastructure, the right to health and a suitable environment for the inmates of the Women’s Annex in Chorrillos Prison (Peru). Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 21, 149–152 (2019).

Barry, L. C., Adams, K. B., Zaugg, D. & Noujaim, D. Health-care needs of older women prisoners: Perspectives of the health-care workers who care for them. J. Women Aging 32, 183–202 (2020).

Hernández-Vásquez, A. & Rojas-Roque, C. Diseases and access to treatment by the Peruvian prison population: An analysis according to gender. Rev. Esp. Sanid. Penit. 22, 9–15 (2020).

Fegadolli, C., Varela, N. M. D. & de Carlini, E. L. A. Uso e abuso de benzodiazepínicos na atenção primária à saúde: Práticas profissionais no Brasil e em Cuba. Cad Saude Publica 35, e00097718 (2019).

Votaw, V. R., Geyer, R., Rieselbach, M. M. & McHugh, R. K. The epidemiology of benzodiazepine misuse: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 200, 95–114 (2019).

Collier, S. & Friedman, S. H. Mental illness among women referred for psychiatric services in a New Zealand women’s prison. Behav. Sci. Law 34, 539–550 (2016).

Fedock, G. L. Women’s psychological adjustment to prison: A review for future social work directions. Soc. Work Res. 41, 31–42 (2017).

Gottfried, E. D. & Christopher, S. C. Mental disorders among criminal offenders. J. Correct. Health Care 23, 336–346 (2017).

Baranyi, G., Cassidy, M., Fazel, S., Priebe, S. & Mundt, A. P. Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder in prisoners. Epidemiol. Rev. 40, 134–145 (2018).

Facer-Irwin, E. et al. PTSD in prison settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis of comorbid mental disorders and problematic behaviours. PLoS ONE 14, e0222407 (2019).

Bedaso, A., Ayalew, M., Mekonnen, N. & Duko, B. Global estimates of the prevalence of depression among prisoners: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress. Res. Treat. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/3695209 (2020).

Aday, R. & Farney, L. Malign neglect: Assessing older women’s health care experiences in prison. J. Bioeth. Inq. 11, 359–372 (2014).

Caravaca-Sánchez, F. & García-Jarillo, M. Alcohol, otras drogas y salud mental en población femenina penitenciaria. Anuario Psicol. Jurídica 30, 47–53 (2020).

Augsburger, A. et al. Assessing incarcerated women’s physical and mental health status and needs in a Swiss prison: A cross-sectional study. Health Justice 10, 8 (2022).

Attilia, F. et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: Diagnostic and therapeutic methods. Riv. Psichiatr. https://doi.org/10.1708/2925.29413 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a public agency Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (CHAMADA FAPERGS/MS/CNPq/SESRS n. 03/2017 PROGRAMA PESQUISA PARA O SUS: GESTÃO COMPARTILHADA EM SAÚDE PPSUS – 2017- PPSUS EFD_00000129). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of this article. The authors are extremely grateful for the support shown by the Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de Porto Alegre and by the Grupo Hospitalar Conceição. Special thanks to Ms. Vânia Naomi Hirakata for contributing to the statistical analysis.

Funding

This work was supported by public agency [CHAMADA FAPERGS/MS/CNPq/SESRS n. 03/2017 PROGRAMA PESQUISA PARA O SUS: GESTÃO COMPARTILHADA EM SAÚDE PPSUS – 2017]—(PPSUS EFD_00000129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K., M.T.G.D. and H.M.T.B. (Conceptualization); L.K. and M.T.G.D. (Data curation); F.M.S.E., L.K. and M.T.G.D. (Formal Analysis); M.T.G.D. (Funding acquisition); L.K., M.T.G.D., A.L.V.S., R.M.D. and H.M.T.B (Investigation); F.M.S.E., L.K., M.T.G.D, A.L.V.S., R.M.D. and H.M.T.B (Methodology); L.K., M.T.G.D., A.L.V.S. and R.M.D. (Project administration); F.M.S.E., L.K., M.T.G.D, A.L.V.S. and R.M.D. (Resources); M.T.G.D., A.L.V.S. and R.M.D. (Software); L.K., M.T.G.D, A.L.V.S., R.M.D. and H.M.T.B (Supervision); L.K., M.T.G.D, A.L.V.S., R.M.D. and H.M.T.B (Validation); F.M.S.E., L.K., M.T.G.D, A.L.V.S., R.M.D. and H.M.T.B (Visualization); F.M.S.E., L.K. and H.M.T.B (Writing – original draft); F.M.S.E., L.K. and H.M.T.B (Writing—review and editing). All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Miranda Seixas Einloft, F., Kopittke, L., Thais Guterres Dias, M. et al. The use of benzodiazepines and the mental health of women in prison: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 13, 4491 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30604-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-30604-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.