Abstract

Loneliness is associated with detrimental consequences for mental and physical health. Even though loneliness affects people of all ages, very few studies have examined its prevalence across the adult lifespan. Additionally, no study has examined the distinction between social and emotional loneliness across the lifespan, even though it has long been considered functionally important. To address these issues, the present study examined the prevalence of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan based on two cohorts (2016/17 and 2017/18) of a nationally representative survey (N ~ 8000 per cohort, age range: 16 to ~ 90). We estimated how similar or distinct patterns of social and emotional loneliness were across the adult lifespan and their consistency across cohorts. The results consistently showed that social and emotional loneliness levels differ as a function of age. Emotional loneliness peaked in younger and older adulthood, whereas social loneliness was stable in early and middle adulthood, before dropping steeply in later stages of life. These findings update basic understanding of loneliness by demonstrating how the experience of different loneliness types may vary across the adult lifespan. In the longer term, the findings have potential societal and clinical importance by informing interventions that target specific loneliness subtypes and age groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Humans are inherently social beings, whose lives are centered around interactions with others1,2. Due to the centrality of social life, the absence of sufficient social connections can be detrimental to our mental and physical well-being3. Indeed, loneliness, or a perceived lack of social connection3,4, has been associated with a range of negative health outcomes, such as higher immunodeficiency, susceptibility to psychiatric disorders, an increased risk for cognitive decline, and higher overall mortality5,6,7,8. As such, loneliness is an urgent public health issue, which requires further attention in order to mitigate its detrimental consequences.

Loneliness is often considered synonymous with social isolation, but these terms are dissociable9. Social isolation is an objective measure of the quantity of an individual’s social interactions, related to factors such as the frequency of social contact and proximity to others. In contrast, loneliness reflects a subjective perception that an individual’s need for social connection is not sufficiently being met by their surroundings10,11,12.

The prevalence of loneliness across the adult lifespan has received increased attention in recent years. Most studies have revealed a non-linear, U-shaped relationship between loneliness and age, whereby loneliness increases during young adulthood and older age, and substantially decreases in middle adulthood3,13,14,15,16,17,18. However, recent large-scale studies have also shown that loneliness has a linear relationship with age (i.e., loneliness gradually increases as people get older19,20,21), as well as a different nonlinear trajectory (i.e., loneliness decreases in young adulthood and gradually peaks from middle adulthood onwards22), or no relationship with age23. As such, even though a majority of prior studies have demonstrated a U-shaped trajectory of loneliness across the lifespan, the results remain mixed overall.

Although many factors could have contributed to these mixed findings (e.g., sociodemographic and health characteristics of the samples20), in this study we consider two factors that have not received sufficient attention in the research literature. First, the majority of studies have treated loneliness as a unidimensional concept, which could have masked relationships between age and different dimensions of loneliness. Loneliness is generally considered a multifaceted construct that is composed of at least two distinct components that have been identified for decades: social and emotional loneliness24. Social loneliness refers to the absence of a desired social network, that is, a wider circle of family, friends and acquaintances that can provide a sense of belonging24,25,26. In contrast, emotional loneliness is related to the lack of one or more attachment figures that one could form an intimate connection with24,25,26. While these two dimensions are correlated, they are distinct states that are associated with different events in someone’s life27,28. For example, social loneliness can occur after moving to a different location, whereas emotional loneliness can follow the death of a loved one26. Given that divergent accounts of the relationship between loneliness and age have been put forward19,20,23, it remains possible that each loneliness dimension has a distinct relationship with age.

A second factor that could have contributed to the variation in prior findings is that very few studies, if any, have investigated social and emotional loneliness across the entirety of the adult lifespan. For example, previous studies on young adults have found that emotional loneliness is more prevalent than social loneliness between adolescence and one’s late twenties29,30. Similar evidence was obtained in a sample of older adults (75+ years), in which emotional loneliness was more prevalent than social loneliness26. However, these prior studies focused only on younger or older adults, thus leaving middle adulthood understudied, and being unable to directly compare different loneliness types across the entire adult lifespan. Moreover, the loneliness measurements (i.e., social and emotional loneliness scale) and sample characteristics (e.g., nationality) in these studies are divergent, which makes comparison between results difficult, given that different national backgrounds and loneliness measures can influence loneliness scores20,31,32. Therefore, the prevalence of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan remains unclear.

In light of this research context, the current project investigates the severity of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan. We use a nationally representative sample of adults aged 16 to ~ 90 to estimate the relationship between age and each of the two loneliness dimensions. More specifically, we use data from two different years of the National Survey for Wales (NSW), an annual survey of approximately 10,000 people in Wales, which included a loneliness questionnaire. We take a multi-level Bayesian estimation approach to analyse the data over two cohorts (2016/17 and 2017/18). As such, we use a data-driven approach to test the extent to which patterns of social and emotional loneliness are similar or distinct across the adult lifespan, as well as how consistent the data are across two large cohorts that cover the entirety of the adult lifespan. We also evaluate the extent to which levels of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan support the differing predictions from previously suggested trajectories of loneliness across the lifespan. The primary value of the current work is to improve basic understanding of the rate of social and emotional loneliness in different stages of adult life. In the longer term, such findings could also ultimately help to inform interventions targeting specific loneliness symptoms across the lifespan.

Materials and methods

Data source

The present study involved secondary analyses of two existing datasets from the 2016/17 and 2017/18 cohorts of the NSW, an annual survey conducted by the UK's Office of National Statistics (ONS). The NSW is a nationally representative sample of the entire adult population (aged 15 and over) of Wales, assessing factors like health status, lifestyle, access to public services, mental wellbeing and loneliness. The design of the NSW is described in more detail in the Welsh Government Technical Report33. In total, there were 21,874 participants across both NSW datasets (10,493 in the 2016/17 dataset and 11,381 in the 2017/18 dataset). Participants in each cohort were randomly chosen to participate from the entire population of Wales. Only participants who completed the loneliness measure in the NSW were included in the study. Thus, the final sample consisted of 8177 individuals (4559 females) from the 2016/17 dataset and 9343 individuals (5,168 females) from the 2018/19 dataset. The age range of participants in the 2016/17 and 2018/19 datasets was 15 to 100 years (M = 55.16, SD = 18.38) and 15 to 90 years (M = 54.2, SD = 18.23), respectively. Age was treated as a continuous variable in this study. In both datasets, over 95% of participants identified as Caucasian (Welsh or British). Additional demographic information for each dataset can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

Social and emotional loneliness measure

Loneliness was measured by the 6-item De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS), which is a shortened version of the 11-item DJGLS34. The 6-item DJGLS contains two 3-item subscales that measure social (e.g., “There are plenty of people I can rely on when I have problems”) and emotional loneliness (e.g., “I experience a general sense of emptiness”). Each item is answered categorically (“Yes” / “More or less” / “No”). This item response model is based on dichotomous item scale scores in which the answer “more or less” always indicates loneliness31. This means, for example, that answers of “yes” or “more or less” are given a score of 1, while answers of “no” are scored as 0. Responses in each subscale are summed to produce a score from 0 to 3, with greater scores indicating greater social or emotional loneliness.

The validity and reliability of the 6-item DJGLS have been empirically tested for use in different age groups and cultures31,34. The 6-item scale has been found to have good internal consistency (α reliability coefficients between .70 and .76) and strong correlations (r correlation coefficients between .93 and .95) with the original 11-item DJGLS, indicating good convergent validity34. The emotional and social subscales have good reliability (α reliability coefficients between .82 to .90 for emotional and α between .85 to .94 for social loneliness)34. Moreover, confirmatory factor analysis has confirmed the existence of each type of loneliness as separate constructs34.

Data analysis approach

We followed a Bayesian estimation approach to modelling35, which we have adopted in recent papers36,37. The main goal was to estimate parameters of interest in regression models of varying complexity and compare the performance of these models. First, we evaluated key parameters of interest from the posterior distribution of our most complex model. Second, we performed model comparison via efficient approximate leave-one-out cross validation (LOO38), to estimate how accurately each model can predict out-of-sample data. In this way, we could estimate the extent to which an increase in model complexity corresponded to an increase in model accuracy.

More specifically, we implemented McElreath’s35 general Bayesian principles in the modelling package “brms”39,40,41 in R version 4.1.142. Given that our primary dependent variable (loneliness score) was a count variable, we modelled the data using a binomial distribution. We computed six models per dataset (2016/17, 2017/18), which built incrementally in terms of complexity. We started with an intercepts-only model (m0). Model m1 included a linear age term and model m1b also included a quadratic age term. Model m2 additionally included loneliness type, and model m3 included a linear age * loneliness type interaction term. Lastly, model m3b additionally included a quadratic age * loneliness type interaction term. Model m3b, therefore, was the full or most complex model in each dataset.

Factors were coded according to a deviation coding style, where factors sum to zero. As such, loneliness type was coded as −0.5 (social) and 0.5 (emotional). Age was centred and standardised. We set priors using a weakly informative approach43, because we currently do not have sufficient knowledge to place more specific constraints on expected results (Table 1). Weakly informative priors place a constrained distribution on expected results, rather than leaving all results to be equally likely (uniform). Also, by using weakly informative priors, we allow for the possibility of larger effects, should they exist in the data43,44,45,46. Given the relatively small effect sizes in the field of psychology in general47, we centred normally distributed priors for effects of interest on zero (i.e., no effect) with a standard deviation of 0.5 (see class “b” in Table 1). That means that prior to running the study, we expected effects closer to zero to be more likely than effects further away from zero.

The formula for the full model (m3b) is specified below, with lcount being the dependent variable, age being the linear age term, age2 being the quadratic age term and ltype being the loneliness type factor (social vs. emotional):

For all six models (m0 to m3b) we subsequently computed LOO to compare out-of-sample prediction accuracy. Lastly, to follow-up our primary analyses, we also ran some further, more exploratory analyses. Given that other demographic and social contact variables have been associated with loneliness in the NSW, such as marital status, health and socioeconomic status (e.g.10), we wanted to run a further model that included a set of additional covariates. By doing so, we wanted to see the extent to which our key parameters of interest changed once additional covariates were added. Therefore, we ran one further model, which expanded model m3b to include five further variables including gender, marital status, number of people in a household, a measure of deprivation and a measure of general health (see Supplementary Materials for details).

Results

Describing social and emotional loneliness across the lifespan

Our primary aim was to investigate the extent to which levels of social and emotional loneliness are similar or distinct across the adult lifespan in two nationally representative cohorts. Social and emotional loneliness scores were largely consistent between the two cohorts (Figs. 1 and 2). Figure 1 shows social and emotional loneliness scores in the two NSW datasets. Most participants reported not experiencing loneliness or low levels of loneliness in both cohorts. Mean scores for social loneliness were 1.04 (SD = 1.15) and 0.99 (SD = 1.12) for the 2016/17 and 2017/18 cohorts, respectively. Additionally, mean scores for emotional loneliness were 0.76 (SD = 0.96) and 0.77 (SD = 0.98) for the 2016/17 and 2017/18 datasets, respectively.

Social and emotional loneliness scores in the two NSW cohorts (2016/17 and 2017/18) (note: bars for social and emotional loneliness are overlapping). Scores for each loneliness type range between 0 (no loneliness) and 3 (severe loneliness). Dashed lines represent mean scores for each loneliness type.

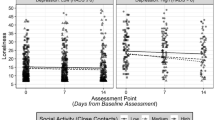

Figure 2 shows the mean social and emotional loneliness scores across the lifespan. Social and emotional loneliness had a different distribution across age. Social loneliness remained relatively stable in early and mid-adulthood and dropped in late adulthood (between 56 and 96 years of age). Emotional loneliness followed a subtle U-shaped distribution, peaking in early and late adulthood, and dropping between 26 and 86 years of age. In addition, social loneliness was higher than emotional loneliness until late adulthood (~ 80 years of age in each cohort), at which point emotional loneliness increased.

Assessing the levels of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan

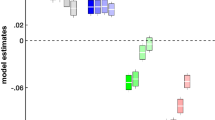

We assessed the levels of loneliness types across the adult lifespan in two ways. First, we considered parameter estimates in the most complex of our primary models. For both sets of analyses (2016/17 and 2017/18 NSW cohorts), model diagnostics were acceptable, and the chains converged well, which means that the models were built without any problems (see Supplementary Figs. 1–4). Additionally, for both analyses, parameter estimates for the most complex model (m3b) are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 2. Parameter estimates were converted from log odds to odds ratios for ease of interpretation. An odds ratio of 1 indicates no effect on the outcome, while an odds ratio of 1.5 indicates a 50% increase in the outcome measure.

Results across both years of the NSW were consistent. The odds ratios for the fixed effects of linear age, quadratic age, and loneliness type were negative, with the lower bound of the interval estimate ranging from 0.8 to 0.9 for linear and quadratic age terms, and 0.5 for loneliness type. These main effects are qualified by the interaction terms, which are directly relevant to our primary aim. The odds ratio for the interactions between both age terms (linear and quadratic) and loneliness type was positive with the lower bound of the interval estimate ranging from 1.1 to 1.2 (Fig. 3, Table 2). This suggests that the shape of the linear and quadratic age effects varied as a function of loneliness type. In other words, the relationship between each loneliness type and age was not the same.

According to the model predictions (Fig. 4), the pattern of social loneliness across age was steeper and curvier than the pattern of emotional loneliness. Therefore, given that social loneliness was coded as a negative factor (− 0.5) and emotional loneliness as a positive factor (+ 0.5), a positive interaction term indicates that the linear and quadratic age effects were more positive for emotional than social loneliness. This interaction effect can be readily seen in Fig. 4, whereby emotional loneliness is well-characterised by a relatively gentle U-shaped function across age. That is, emotional loneliness peaks in the youngest and oldest cohorts. In contrast, social loneliness remains relatively stable in the first half of the age cohort (although higher than emotional loneliness), and then reduces in the second half of the age cohort. The centre point (i.e., zero) in Fig. 4 resembles the mean age in each cohort, which was 54 and 55 years for 2016/17 and 2017/18, respectively.

Model comparison (models 1-6) for 2016/17 (a) and 2017/18 (b) NSW cohorts. In both analyses, model m0 included an overall intercept; model m1 added a linear age term; model m1b added a quadratic age term; model m2 added a predictor for loneliness type (social vs emotional); model m3 added a linear age * loneliness type interaction; model m3b (the full model) added a quadratic age * loneliness type interaction. “ELPD_LOO” refers to the estimate of the expected log pointwise predictive density. “LOO” refers to leave-one-out estimated cross validation. Error bars depict the standard error of the mean. The “17” and “18” suffixes in each model indicate the 2016/17 and 2017/18 NSW cohorts, respectively.

We also ran an additional exploratory model with factors that are frequently associated with loneliness as covariates (i.e., gender, marital status, number of people in a household, a measure of deprivation and a measure of general health). Once these covariates were added in, the primary results, which involved interaction terms between linear and quadratic age terms and loneliness type, remained the same in terms of strength and direction (Supplementary Figs. 5–6, Supplementary Table S2). That is, there was still a clear positive interaction term for each age term and loneliness type. We take this finding as suggestive evidence that whatever set of variables contribute to the relationship between age and loneliness type, it cannot be easily described by a host of demographic, health and social contact variables that have previously been associated with loneliness.

The second way we assessed loneliness across the adult lifespan was by comparing out-of-sample predictive accuracy across models. The pattern of predictive accuracy across models was consistent across both datasets (Fig. 5). Compared to the intercepts-only model (m0), adding loneliness type into the model (m2) improved out-of-sample predictive accuracy more than adding either age term (m1 and m1b). In fact, error bars for age models overlapped with the intercepts-only model, which suggests that they were largely similar. Likewise, error bars for the models with the interaction terms (m3 and m3b) also overlapped with the model with loneliness type (m2), which again suggests that these models performed in a largely similar manner in terms of out-of-sample predictive accuracy.

Discussion

This is the first large-scale study to investigate the levels of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan. Across both datasets, the results demonstrated a consistent relationship between loneliness type and age. In both datasets, levels of social loneliness peaked in early and middle adulthood, and dropped in later adulthood. In contrast, emotional loneliness followed a gentle U-shaped distribution, peaking in early and late adulthood, and dropping in middle adulthood. These results provide large-scale empirical evidence that demonstrates how levels of social and emotional loneliness, which have long-been considered functionally important for individuals and society24, vary across the adult lifespan. In the following, we consider implications for understanding the prevalence of loneliness in society, as well as for designing future interventions, and we also highlight limitations of the current work.

Comparison of results to previous models of loneliness and age

We first consider how our findings fit with the predictions from prior models of loneliness. The distribution of emotional loneliness supports a non-linear trajectory of the relationship between loneliness and age3,13,14,21. In line with previous findings, emotional loneliness was at its highest points in young and older adulthood26,29,30. Although the cross-sectional nature of the current design is unable to demonstrate which factors are driving such a relationship, the findings are intuitively consistent with past work, which has associated emotional loneliness with the presence of an intimate partner26,29,48,49. As such, emotional loneliness would be higher before intimate relationships are established (younger age) and once they have ended (older age), for example due to divorce or a partner’s death.

Social loneliness, however, did not follow predictions from prior models. For example, social loneliness levels did not increase in older age19,20 or show a U-shaped distribution3,13,14,21. Instead, social loneliness showed a marked decrease from late 50’s onwards. These results, therefore, are discrepant with previous studies that have shown that social loneliness gradually decreases from adolescence to young adulthood29,30, and then increases in the later stages of adulthood26.

We cannot say with certainty what accounts for this discrepancy between past studies and our findings nor can we say what factors are driving the pattern of social loneliness across age in our data. Cross-sectional data is simply not the right kind of data to make those kinds of claims50. Instead, we see the value of the current work being the comprehensive description of the pattern of different types of loneliness across age, which has been replicated in two large, nationally representative samples. Moreover, such value was only made possible by making the distinction between loneliness types and by having a sample that is sufficiently large to span the entire adult age range, which past work has not done. Past work tended to focus on age groups, such as groups of younger or older individuals, but not both (e.g.,26,29,30), which means that comparisons between age groups were not possible.

At this stage of understanding, therefore, we consider the comprehensive nature of our data and the somewhat discrepant results with past studies to be fertile ground for future research to assess or generate different hypotheses regarding social loneliness, which may have more causal or mechanistic foundations, and then test them using appropriate methods. For example, a prominent hypothesis that could explain the relationship between social loneliness and age is the socioemotional selectivity theory51,52. According to this view, physical limitations (e.g., reduced mobility, health issues) that typically decrease the possibility of extensive socialising make older adults prioritise the quality over the quantity of social relationships, which could act as a protective factor for social loneliness. In other words, according to this theory, older adults prioritize fewer but more meaningful relationships, which decreases the risk of social loneliness as maintaining a wide network of social connections is no longer a priority. Further studies could assess this and other hypotheses to get a better understanding of the experience of social loneliness in later life.

Implications for interventions

The findings from the current study could also help to guide the design of loneliness interventions. In the past, ignoring variation in different types of loneliness across the lifespan might have been one reason for the limited effectiveness of previous loneliness interventions53,54,55. For instance, based on the current findings, middle-aged individuals are much more likely to experience social than emotional loneliness, and could thus benefit more from interventions that specifically tackle social loneliness (e.g., participating in social activities as part of a group56), as opposed to interventions that treat loneliness as a unidimensional construct. Based on this, future research should examine how interventions that target a specific loneliness subtype might help alleviate loneliness levels across the lifespan.

Limitations and future directions

Even though the present study provides novel insight into the experience of loneliness across the lifespan, the results face important limitations. As mentioned before, data from the two NSW cohorts are cross-sectional, which makes it hard to determine causal relationships between age and social and emotional loneliness50. Indeed, it is unclear whether the trends observed in this study are cohort-specific, or if they will be carried on as the younger members of the NSW datasets grow older. Further studies could overcome this issue by acquiring longitudinal data to examine the experience of social and emotional loneliness in a single aging cohort.

Another thing to consider is that the findings only focus on one country. This could be problematic because loneliness levels can vary considerably between different regions20,21,32. For example, previous research has demonstrated that Eastern European countries are characterised by a gradual increase of both loneliness and age, whereas Western European countries are associated with a rapid increase in loneliness only after ~ 70 years of age17. Additionally, recent findings from 237 countries have shown that people in collectivist countries tend to feel less lonely compared to people in individualistic cultures57. Future research should compare findings from different regions to obtain a more holistic view of the severity of social and emotional loneliness across the lifespan in different cultures.

A further potential limitation is the use of the DJGLS34 as a measurement of social and emotional loneliness. It has been argued that the distinction between social and emotional loneliness in the DJGLS could be partially driven by the valence of items (that is, three negatively phrased items for emotional loneliness and three positively phrased items for social loneliness), as opposed to two underlying factors that correspond to each loneliness subtype28,58. However, any account of our findings needs to explain the pattern of data for each loneliness type as a function of age, rather than just an average difference between loneliness types. And, to our knowledge, there is currently no clear theoretical basis or robust evidence that demonstrates that the way people respond to positively and negatively phrased items (as opposed to the way they experience loneliness) is what changes as a function of age. Thus, although it is possible that the valenced nature of the items could contribute to our findings, such a proposal currently lacks theoretical or empirical justification. To contextualise this point further, this limitation is not specific to the current study, as previous studies that estimated the prevalence of social and emotional loneliness across the lifespan also used scales that dichotomised social and emotional loneliness based on positively or negatively phrased items26,29,30. As such, we suggest that the development of a revised scale, which can distinguish between different types of loneliness in a cleaner manner, would be an important avenue for future research.

Constraints on generality

Simons and colleagues59 recently argued that it can be useful to place explicit constraints on the generality of findings, which we do here, in terms of the conceptualisation of “age effects”. We do not take the present results to mean that the experience of loneliness across the lifespan is determined by a “pure” chronological effect related to age. Instead, the “age” factor in our analyses is indicative of a complex set of life events that could underlie the experience of loneliness across the adult lifespan. Indeed, different stages in life might be characterised by different events that can drive levels of social and emotional loneliness (e.g., death of a partner that typically occurs in older age might lead to higher emotional loneliness levels). This is consistent with recent meta-analytic findings suggesting that the severity of loneliness across the lifespan is not an age-specific phenomenon but is driven more by personal experiences that may be associated with age in the general population23. We think that future work that further characterises the relationship between age, life experiences and loneliness would be valuable.

Data availability

The data used in this work are open and can be freely downloaded from the U.K. Data Service website (https://ukdataservice.ac.uk). Furthermore, in accordance with current open science suggestions60, we release R Markdown files that record each stage of our analytical process to aid transparency, data sharing, and reproducibility (https://osf.io/yuw6h/).

References

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117, 497–529 (1995).

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S. & Boomsma, D. I. Evolutionary mechanisms for loneliness. Cognit. Emot. 28, 3–21 (2014).

Luhmann, M. & Hawkley, L. C. Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Dev. Psychol. 52, 943–959 (2016).

Hawkley, L. C. et al. From social structural factors to perceptions of relationship quality and loneliness: the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 63, S375–S384 (2008).

Beutel, M. E. et al. Loneliness in the general population: prevalence, determinants and relations to mental health. BMC Psychiatry 17, 97 (2017).

Boss, L., Kang, D. H. & Branson, S. Loneliness and cognitive function in the older adult: a systematic review. Int. Psychogeriatr. 27, 541–553 (2015).

Brown, E. G., Gallagher, S. & Creaven, A. M. Loneliness and acute stress reactivity: A systematic review of psychophysiological studies. Psychophysiology 55, e13031. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13031 (2017).

Kuiper, J. S. et al. Social relationships and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Ageing Res. Rev. 22, 39–57 (2015).

Perissinotto, C. M. & Covinsky, K. E. Living alone, socially isolated or lonely: what are we measuring?. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 29, 1429–1431 (2014).

Byrne, C., Saville, C. W. N., Coetzer, R. & Ramsey, R. Stroke survivors experience elevated levels of loneliness: a multi-year analysis of the National Survey for Wales. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 37, 390–407 (2021).

Cacioppo, J. T., & Patrick, W. Loneliness: human nature and the need for social connection (W W Norton & Co, 2008).

Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., Ronzi, S. & Hanratty, B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 102, 1009–1016 (2016).

Hawkley, L. C., Buecker, S., Kaiser, T. & Luhmann, M. Loneliness from young adulthood to old age: explaining age differences in loneliness. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 46, 39–49 (2020).

Lasgaard, M., Friis, K. & Shevlin, M. “Where are all the lonely people?” A population-based study of high-risk groups across the life span. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51, 1373–1384 (2016).

Pinquart, M. & Sorensen, S. Influences on loneliness in older adults: a meta-analysis. BASP 23, 245–266 (2001).

Qualter, P. et al. Loneliness across the life span. Perspect Psychol Sci. 10, 250–264 (2015).

Victor, C. R. & Yang, K. The prevalence of loneliness among adults: a case study of the United Kingdom. J. Psychol. 146, 85–104 (2012).

Weeks, M. S. & Asher, S. R. Loneliness in childhood. Adv Child Dev Behav 42, 1–39 (2012).

Franssen, T., Stijnen, M., Hamers, F., & Schneider, F. Age differences in demographic, social and health-related factors associated with loneliness across the adult life span (19–65 years): a cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health 20 (2020).

Hutten, E. et al. Risk factors of loneliness across the life span. J Soc Pers Relat 39, 1482–1507 (2021).

Yang, K. & Victor, C. Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing Soc 31, 1368–1388 (2011).

Clark, M., Bonnici, J. & Azzopardi, A. Loneliness in Malta: findings from the first national prevalence study. J Soc Pers Relat 38, 2751–2771 (2021).

Mund, M., Freuding, M. M., Möbius, K., Horn, N. & Neyer, F. J. The stability and change of loneliness across the life span: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 24, 24–52 (2021).

Weiss, R. S. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation (MIT Press, 1973).

Dahlberg, L. & McKee, K. J. Correlates of social and emotional loneliness in older people: evidence from an English community study. Aging Ment Health 18, 504–514 (2013).

Fierloos, I. N. et al. (2021). Socio-demographic characteristics associated with emotional and social loneliness among older adults. BMC Geriatr. 21 (2021).

DiTommaso, E. & Spinner, B. Social and emotional loneliness: a re-examination of Weiss’ typology of loneliness. Pers. Individ. Differ. 22, 417–427 (1997).

Dykstra, P. A. & Fokkema, T. Social and emotional loneliness among divorced and married men and women: comparing the deficit and cognitive perspectives. BASP 29, 1–12 (2007).

Diehl, K., Jansen, C., Ishchanova, K. & Hilger-Kolb, J. Loneliness at universities: determinants of emotional and social loneliness among students. IJERPH 15, 1865 (2018).

van Soest, T., Luhmann, M. & Gerstorf, D. The development of loneliness through adolescence and young adulthood: Its nature, correlates, and midlife outcomes. Dev. Psychol. 56, 1919–1934 (2020).

de Jong Gierveld, J. & van Tilburg, T. The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. Eur. J. Ageing 7, 121–130 (2010).

Hawkley, L. C., Duvoisin, R., Ackva, J., Murdoch, J. C., & Luhmann, M. Loneliness in older adults in the USA and Germany: Measurement invariance and validation. Working Paper Series, NORC at the University of Chicago, Paper 2015–002 (2015).

Helme, M & Brown, Z. National Survey for Wales 2017–18 Technical Report. Welsh Government; https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-05/national-survey-for-wales-technical-report-2017-18_0.pdf. (2018).

de Jong Gierveld, J. & van Tilburg, T. A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness. Res Aging 28, 582–598 (2006).

McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking; A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan. (2nd ed.). (CRC Press, 2020).

Bara, I., Binney, R. & Ramsey, R. Investigating the role of cognitive control in aesthetic judgments. J. Vis. 21, 1940 (2021).

Bara, I., Darda, K. M., Kurz, A. S., & Ramsey, R. Functional specificity and neural integration in the aesthetic appreciation of artworks with implied motion (2021).

Vehtari, A., Gelman, A. & Gabry, J. Practical Bayesian model evaluation using leave-one-out cross-validation and WAIC. Stat. Comput. 27, 1413–1432 (2016).

Bürkner, P. C. (2017). brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J. Stat. Softw. 80, 1–28 (2017).

Bürkner, P. C. Advanced Bayesian multilevel modeling with the R package brms. R J 10, 395–411 (2018).

Kurz, A. S. Statistical Rethinking with brms, ggplot2, and the tidyverse (2nd ed.); 10.5281/zenodo.4302550 (2020).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; https://www.R-project.org/ (2021).

Gelman, A. Prior distributions for variance parameters in hierarchical models (Comment on article by Browne and Draper). Bayesian Anal. 1 (2006).

Gelman, A., & Hill, J. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (1st ed.) (Cambridge University Press, 2007).

Gelman, A. et al. Bayesian Data Analysis (3rd ed.) (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2013).

Lemoine, N. P. Moving beyond noninformative priors: why and how to choose weakly informative priors in Bayesian analyses. Oikos 128, 912–928 (2019).

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. AMPPS 2, 156–168 (2019).

Chiao, C., Chen, Y. H. & Yi, C. C. Loneliness in young adulthood: Its intersecting forms and its association with psychological well-being and family characteristics in Northern Taiwan. PLoS ONE 14, e0217777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0217777 (2019).

Nicolaisen, M. & Thorsen, K. Who are lonely? Loneliness in different age groups (18–81 years old), using two measures of loneliness. Int J Aging Hum Dev 78, 229–257 (2014).

Wang, X. & Cheng, Z. Cross-sectional studies: strengths, weaknesses, and recommendations. Chest 158, S65–S71 (2020).

Carstensen, L. L. Social and emotional patterns in adulthood: support for socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychol Aging 7, 331–338 (1992).

Carstensen, L. L. Evidence for a life-span theory of socioemotional selectivity. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 4, 151–156 (1995).

Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., & Donnelly, M. Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: a scoping review of reviews. BMC Public Health 20 (2020).

Gardiner, C., Geldenhuys, G. & Gott, M. Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: an integrative review. Health Soc Care Community 26, 147–157 (2016).

Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C. & Cacioppo, J. T. A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. PSPR 15, 219–266 (2010).

Dickens, A. P. et al. Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 11, 647 (2011).

Barreto, M. et al. Loneliness around the world: age, gender, and cultural differences in loneliness. Pers. Individ. Differ. 169, 110066 (2021).

Buz, J., Urchaga, D., & Polo, M. E. Factor structure of the de Jong Gierveld loneliness scale in Spanish elderly adults. An. de Psicol. 30 (2014).

Simons, D. J., Shoda, Y. & Lindsay, D. S. Constraints on generality (COG): a proposed addition to all empirical papers. Perspect Psychol Sci 12, 1123–1128 (2017).

Munafò, M. R. et al. A manifesto for reproducible science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M. and R.R. designed the study, analysed the data, evaluated the results, and visualised the figures. A.M. wrote the original manuscript draft. J.M. and R.R. conceptualised the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Manoli, A., McCarthy, J. & Ramsey, R. Estimating the prevalence of social and emotional loneliness across the adult lifespan. Sci Rep 12, 21045 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24084-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-24084-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.