Abstract

PA-enhanced content causes astringency in persimmon fruit. PCNA persimmons can lose their astringency naturally and they become edible when still on the tree, which allows for conserves of physical and financial resources. C-PCNA persimmon originates in China. Its deastringency trait primarily depends on decreased PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization at the late stage of fruit development. Although some genes and transcription factors that may be involved in the deastringency of C-PCNA persimmon have been reported, the expression patterns of these genes during the key deastringency stage are reported less. To investigate the variation in PA contents and the expression patterns of deastringency-related genes during typical C-PCNA persimmon ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’ fruit development and ripening, PA content and transcriptional profiling were carried out at five late stages from 70 to 160 DAF. The combinational analysis phenotype, PA content, and DEG enrichment revealed that 120–140 DAF and 140–160 DAF were the critical phases for PA biosynthesis reduction and PA insolubilization, respectively. The expression of PA biosynthesis-associated genes indicated that the downregulation of the ANR gene at 140–160 DAF may be associated with PA biosynthesis and is decreased by inhibiting its precursor cis-flavan-3-ols. We also found that a decrease in acetaldehyde metabolism-associated ALDH genes and an increase in ADH and PDC genes might result in C-PCNA persimmon PA insolubilization. In addition, a few MYB-bHLH-WD40 (MBW) homologous transcription factors in persimmon might play important roles in persimmon PA accumulation. Furthermore, combined coexpression network analysis and phylogenetic analysis of MBW suggested that three putative transcription factors WD40 (evm.TU.contig1.155), MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203), might connect and co-regulate both PA biosynthesis and its insolubilization in C-PCNA persimmon. The present study elucidated transcriptional insights into PA biosynthesis and insolubilization during the late development stages based on the C-PCNA D. kaki genome (unpublished). Thus, we focused on PA content variation and the expression patterns of genes involved in PA biosynthesis and insolubilization. Our work has provided additional evidence on previous knowledge and a basis for further exploration of the natural deastringency of C-PCNA persimmon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diospyros kaki Thunb. is a member of the family Ebenaceae and is among the important fruit trees cultivated and harvested worldwide1. Based on genetic traits and astringency removal, persimmon varieties can be classified into pollination-constant non-astringent (PCNA), pollination-variant non-astringent (PVNA), pollination-variant astringent (PVA), and pollination-constant astringent (PCA) types2. The Chinese PCNA (C-PCNA) and Japanese PCNA (J-PCNA) persimmon can lose astringency naturally on the tree without any postharvest treatment but have different proanthocyanidin (PA) accumulation mechanisms3,4. The characteristic of losing astringency in J-PCNA and C-PCNA persimmon is genetically controlled by a recessive and a dominant allele, respectively5. Because of dominant inheritance, the C-PCNA genotype is often selected as the superior parent for persimmon breeding programs.

Both the “dilution effect” and “coagulation effect” contribute to the deastringency of C-PCNA persimmon fruit at the late stage6. The “dilution effect” means that PA biosynthesis is reduced with the fruit grows larger, resulting in a decrease in the proportion of soluble PA content in persimmon fruit7,8. PAs are synthesized via the chorismic acid pathway, phenylpropane metabolic pathway, flavonoid synthesis and proanthocyanidin pathway9. The structural genes encoding the enzymes have been identified in the three pathways, including chalcone isomerase (CHI), chalcone synthase (CHS), leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), and anthocyanidin reductase (ANR)10. The “coagulation effect” refers to losing astringency by PA insolubilization by converting soluble PAs into insoluble PAs with acetaldehyde6. The acetaldehyde metabolic pathway plays an important role in the astringency loss of PCNA persimmon11,12 and is catalyzed by pyruvate decarboxylase (PDC), alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH)13,14.

Transcription factors involved in PA biosynthesis have been identified previously. The R2R3MYB, bHLH, and WD40 (MBW) complex regulates the expression of the structural genes DFR, ANS, and ANR of late flavonoid/phenylpropanoid metabolism15. The expression of PA biosynthesis genes is specifically induced by AtTT2 (AtMYB123), AtTT8 (AtbHLH042), and AtTTG1 (WD40-repeat protein) in Arabidopsis thaliana16. In strawberries, FaTTG1 can form a complex with FaMYB9/FaMYB11 and FabHLH3, which increases the accumulation of PA by upregulating the expression of ANS and LAR17. In persimmon, reduced expression of DkMYB4 in J-PCNA leads to the downregulation of PA biosynthesis during the early stages18, and in C-PCNA, reduced expression of DkMYB14 results in the nonastringency, which directly represses PA biosynthesis and promotes its insolubilization, leading to nonastringency19. A bHLH gene (DkMYC1) involved in PA synthesis regulation was isolated from ‘Luotian-tianshi’, and the expression pattern of DkMYC1 was correlated with PA accumulation and the expression patterns of DkANR and DkF3′5′H20.

Several studies have tried to elucidate the underlying molecular basis for C-PCNA persimmon deastringency, either by ethanol or by 40 °C water treatments via transcriptome sequencing. These procedures have no doubt provided crucial insight into the deastringency process21,22; however, C-PCNA persimmon can lose its astringency naturally. The PA biosynthesis and insolubilization in C-PCNA persimmon have not been adequately explained in the natural state, especially at the late developmental stages of fruit. In this study, fruits from the C-PCNA genotype ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’ persimmon were specifically collected at five later stages, as natural deastringency occurs late on the C-PCNA persimmon tree. In addition, the completion of the C-PCNA D. kaki reference genome (unpublished) has facilitated the genome-wide analysis of dynamic gene expression during fruit development; thus, the PA content combined with RNA-seq analysis at key late development stages can provide basic support for C-PCNA persimmon natural astringency loss.

Material and methods

Plant material

Fruits of C-PCNA persimmon (D.kaki, variety ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’) at five developmental stages (T1 = 70, T2 = 100, T3 = 120, T4 = 140, T5 = 160 DAF) were harvested from Yuanyang County, Henan Province, China (34° 55′ 18″–34° 56′ 27″ N, 113° 46′ 14″–113° 47′ 35″ E). The collection and conservation of plant material in this study complied with relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. Fresh material was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at − 80 °C until the PA content and RNA extraction were analyzed.

Extraction and determination of PAs

Approximately 2.5 g (precise weight) of the persimmon fruit powder was extracted with 80% (v/v) ethanol in an ultrasonic bath for 30 min, and the precipitates were suspended in 1% HCl-MeOH for insoluble PA extraction. Soluble and insoluble PA contents were detected using the Folin-Ciocalteu method as described by Oshida et al.23.

RNA extraction, transcriptome sequencing, and data analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the UNlQ-10 Column TRIzol Total RNA Isolation Kit (B511321; Sangon, Shanghai, China). The quality and quantity of the RNA were tested on a 1% agarose gel and then assessed on a Merinton SMA4000 spectrophotometer (Merinton Inc., Beijing, China). The paired-end cDNA sequencing libraries of fruits at five stages were prepared with three biological replicates and then sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). The files of raw reads were cleaned by removing adapter sequences and then the clean reads were mapped to the hexaploid C-PCNA persimmon genome (variety ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’, unpublished).

DEseq2 was used to detect the DEGs24, with a padj ≤ 0.05 and |log2-fold change|≥ 1. Gene Ontology (GO) (www.geneontology.org)25 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) (www.kegg.jp/kegg/kegg1.html)26 databases were used for functional enrichment analysis by ClusterProfiler (3.8.1)27. The R packages Cluster, Biobase, and Q-value were used to display the expression profiles of the DEGs in the five stages using K-means clustering. Heatmaps were prepared with the online website Hiplot. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software (v 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The coexpression networks were constructed using DEGs and were analyzed using the R package WGCNA28 and visualized using Cytoscape (v3.9.1) and its plugin cytoHubba29.

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA for the RNA-seq analysis was reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the TRUE-script First-Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Kemix, Beijing, China). Reactions were run on a LightCycler 480 II (Roche) with a 96-well plate. The reaction conditions for each gene were 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 45 cycles of 5 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 55–60 °C. Three technical replicates were performed for each gene. GAPDH was used as the reference gene30. The RT-qPCR primers are listed in Table S1.

Identification of MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex members in C-PCNA persimmon

To identify MYB-bHLH-WD40 Complex Members in the persimmon genome, local tBLASTp (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) (E-value ≤ 1e−5) was performed using the sequences of homologous MBW complex proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana16,31, Malus × domestica32, Vitis vinifera33,34,35, and Fragaria × ananassa17 (Table S2). The online website Pfam (https://pfam.xfam.org/) was used to remove sequences without conserved MYB_DNA-binding (PF00249.30, PF13921.5), bHLH-MYC_N (PF14215.5), or WD40 (PF00400.31) domains (Table S2). Multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis were implemented using Clustal X36 and MEGA 537 software, respectively.

Result

Phenotype and PA content of C-PCNA persimmon fruit

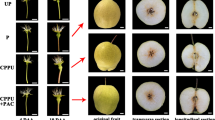

To evaluate the C-PCNA persimmon deastringency process, the fruit’s late developmental stages were grouped into 5 time points (T1–T5) and the fruits were harvested at 70, 100, 120, 140, and 160 days after flower (DAF) (Fig. 1a). Morphological differences were measured based on the changes in fruit size and weight. Persimmon fruit experienced the fastest growth stage from 120 to 140 DAF, with a 39.67–59.27 g weight, and then grew slowly until deastringency (Fig. 1b). During the ‘expansion’ phase, the soluble and insoluble PA contents decreased, followed by a continuous decrease in the soluble PA content in the T4-T5 stages and a significant increase in the insoluble PA content. This resulted in the astringency loss of ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’ persimmon fruit at stage T5 (Fig. 1c).

Five developmental stages of C-PCNA persimmon ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’. (a) Fruit morphology. (b) Mean fruit weight and diameter. (c) Soluble PAs, insoluble PAs, and total PA content. Values are the means of four replicates. **Indicates a significant difference at P < 0.01. * indicates a significant difference at P < 0.05.

RNA-Seq of C-PCNA persimmon developing fruit

After the low-quality reads, the transcriptome sequencing of the ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’ fruit at five developmental stages yielded 99.24 GB of data. Each filtered sample consisted of 6.79 GB of high-quality data with a Q30 base percentage of 95.28% on average, approximately 87.61% of the reads could be with the reference D. kaki genome, and 3,472 novel genes were also identified. These results indicated that sequencing data accuracy was sufficient for further analysis. A principal component analysis (PCA) based on Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values separated the samples into five distinct groups, with each sample making a separate group with its replicates, indicating that there were good correlations and differences among the samples (Fig. 2a). To analyze the expression variabilities associated with C-PCNA persimmon fruit PA biosynthesis and insolubilization at different developmental stages, genes in four pairwise transcriptome groups (T2 vs T1, T3 vs T2, T4 vs T3, and T5 vs T4) were compared. In all, 7,102 genes were significantly differentiated in the four groups, including 2,851 DEGs in T2 vs T1, 2,428 DEGs in T3 vs T2, 2,996 DEGs in T4 vs T3, and 1,914 DEGs in T4 vs T3. The Venn diagram shows that 1,484, 1039, 1,384, and 793 DEGs were differentially expressed in the four respective groups (Fig. 2b–e). Most of the DEGs were downregulated in the control groups. The reliability of the transcriptomic results was confirmed by the consistent gene expression trend of 9 DEGs, which was observed using real-time quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis (Fig. S1) compared with the transcriptome FPKM data.

Overview of the C-PCNA Persimmon Developing Fruit transcriptome. (a) Principal component analysis. (b) Summary of DEGs in all combinations of developmental stage comparisons. The number of total DEGs (c), upregulated DEGs (d), and downregulated DEGs (e) are presented by Venn diagrams (|log2-fold change|> 1 and padj < 0.05).

Functional enrichment analysis of DEGs

The GO and KEGG databases were used to further analyze DEGs in four comparison groups (T2 vs T1, T3 vs T2, T4 vs T3, and T5 vs T4) using padj < 0.05 to indicate a significant difference. The results of GO functional enrichment analysis revealed significant enrichment in four terms associated with PA transport: UDP-glycosyltransferase, glucosyltransferase, drug transmembrane transporter, and transferase activities. GO terms of glucosyltransferase activity were observed in T2 vs T1, T4 vs T3, and T5 vs T4, and the other three terms were only shared in T5 vs T4. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis revealed that T4 vs T3 had enriched phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. The significantly enriched KEGG pathway term flavonoid biosynthesis was shared in T4 vs T3 and T5 vs T4. The two candidate KEGG pathways were considered to be heavily involved in PA accumulation. Our results suggest that the T3–T4 stages may be a key developmental period for the persimmon PA biosynthesis process phenylpropane metabolic pathway and flavonoid synthesis proanthocyanidin pathway. Stages T4-T5 may be involved in persimmon PA transport and the subsequent process (Fig. S2).

Gene expression trends during C-PCNA persimmon fruit development

Six gene profiles based on their expression patterns were clustered together, as shown in Fig. 3a. The genes within these 6 expression profiles were analyzed by KEGG annotation (Fig. 3b). Cluster 2 comprised 1,090 DEGs and their expression showed a downregulating trend from T1 to T5, and these genes rapidly decreased between T2 and T4. Cluster 5 contained 1,332 DEGs, and their expression increased at late time points. The expression pattern of cluster 2 was positively consistent with soluble PA and total PA content (Fig. 1b), whereas 5 was positively aligned with insoluble PA content. DEGs in cluster 2 were significantly enriched in flavonoid biosynthesis and photosynthesis, where flavonoid biosynthesis had an enrichment factor of nearly 0.4, indicating greater intensity. The plant hormone signal transduction and MAPK signaling pathways were significantly enriched in cluster 5. Among those, some of the final metabolites of flavonoid biosynthesis are proanthocyanins. The results of the functional classification analysis of the common expression patterns of DEGs combined with KEGG showed that genes in cluster 2 and cluster 5 might be associated with PA accumulation and were selected for subsequent analysis.

Gene expression profiles and KEGG enrichment analysis of the DEGs in the six common expression clusters composing the fruit transcriptome. (a) Heatmap of the overall common expression pattern. Heat maps depict the normalized gene expression values, which represent the mean value of three biological replicates. (b) Expression patterns and KEGG pathway annotations of 6 clusters. Each line represents the normalized gene expression values for an individual transcript. The y-axis of each cluster is the pathway name, while the x-axis represents the rich factor. Significantly overrepresented KEGG categories are represented by red dots.

DEGs related to PA biosynthesis and insolubilization

PA accumulation gene expression levels across the five developmental stages were investigated by generating heat maps (Fig. 4). We focused on the 43 DEGs involved in the PA biosynthesis and insolubilization pathway, which included 18 genes from cluster 2, 8 from cluster 5, 7 from cluster 6, 5 from cluster 4, 3 from cluster 1, and 2 from cluster 3. Since the aim was to identify genes associated with PA content variation in the C-PCNA persimmon, our analysis was focused on DEGs in clusters 2 and 5. Nearly all DEGs from cluster 2 were downregulated in T4 vs T3 and T5 vs T4. Most of the cluster 2 genes were involved in PA biosynthesis, such as DAHPS (evm.TU.contig8955.26) and DHD/SDH (evm.TU.contig8908.198), the precursors of proanthocyanin biosynthesis that participate in the chorismic acid pathway. PAL (evm. TU.contig9504.51, evm.TU.contig3686.428), C4H (evm.TU.contig22.251), and 4CL (evm.TU.contig7272.385) are phenylpropanoid genes. ANR (evm.TU.contig4466.754), ANS (evm.TU.contig5828.5), CHS (evm.TU.contig4175.257), F3’H (evm.TU.contig7272.244), F3′5'H (evm.TU.contig31.16), and F3H (evm.TU.contig4466.49) are involved in flavonoid synthesis and the proanthocyanidin pathway. Cluster 5 DEGs, however, were upregulated in T5 vs T4, and most of these genes were involved in PA insolubilization, such as PDC (evm.TU.contig3684.117, evm.TU.contig4466.583, evm.TU.contig8029.113, evm.TU.contig9507.111), ADH (evm.TU.contig2067.296, evm.TU.contig4397.68), and ALDH (evm.TU.contig7272.653), which take part in acetaldehyde metabolism. However, the MATE gene (evm.TU.contig2065.66) was significantly downregulated at T4 vs T3, which might be involved in transporting PA to the vacuole. This study revealed that PA biosynthesis-associated genes were highly downregulated in T4 vs T3 and T5 vs T4, whereas PA insolubilization genes were highly upregulated in T5 vs T4, providing a reasonable explanation for the variation in PA content at stages T4–T3 and T5–T4.

Expression patterns of 43 DEGs involved in PA biosynthesis and insolubilization. PA biosynthesis pathways include the chorismic acid pathway, phenylpropane pathway, flavonoid synthesis and proanthocyanidin-specific pathway. PA insolubilization refers to converting soluble PA into insoluble PA with acetaldehyde metabolism. Heatmaps depict the normalized gene expression values, which represent the mean value of three biological replicates.

Phylogenetic analysis and expression patterns of the persimmon MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex

It has been reported that an MBW complex consisting of MYB, bHLH, and WD40 is a critical factor for PA biosynthesis. Our study discovered a total of 14 R2R3-MYB, 13 bHLH, and 13 WD40 transcription factors from the D.kaki genome. These transcription factors clustered with homologous MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex genes of A. thaliana, V. vinifera, and F. ananassa (Fig. 5a–c). Among these transcription factors, only 6 R2R3-MYB, 5 bHLH, and 2 WD40 genes were differentially expressed during C-PCNA persimmon fruit development, so these were used for further analysis. Of the 6 R2R3-MYB family genes, 5 showed significantly decreased expression at T4 vs T3. The evm.TU.contig8910.486 and evm.TU.contig7396.13 gene expression showed a remarkably positive correlation with total PA content (P < 0.05), where evm.TU.contig8910.486 was from cluster 2. All 5 bHLH family genes were downregulated at T4 vs T3, and of these 5 genes, the expression of evm.TU.contig1398.203 and evm.TU.contig8910.303 cluster 2 genes presented a positive correlation with total PA content (P < 0.05). Only 1 WD40 gene, evm.TU.contig1.155, from cluster 5 exhibited a significantly negative correlation with soluble PA content (P < 0.01).

Weighted gene coexpression network analysis

To construct a potential regulatory network of PA accumulation in the C-PCNA persimmon, weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) was performed using 7,102 DEGs, and 15 merged coexpression gene modules were identified. Among these modules, the brown module contained 904 genes, which had a significant and positive correlation with soluble PA (r = 0.76, P = 0.001) and total PA content (r = 0.94, P = 2e−07). The yellow module (864 DEGs) had a significant negative correlation with insoluble PA content (r = 0.75, P = 0.001) (Fig. 6a). This indicates that the brown and yellow modules may have a closer association and more significant correlations with PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization, respectively.

Weighted gene coexpression network analysis. (a) Gene modules defined using WGCNA and the association with soluble PA, insoluble PA, and total PA content. The numbers in the heatmap show the P-value (lower) and the correlation (upper). (b) The linkages of PA biosynthesis and insolubilization DEGs in yellow and brown modules, and the circles are sized by the gene connectivity.

Strikingly, the brown module genes included the structural genes DAHPS (evm.TU.contig8955.26), PAL (evm.TU.contig9504.51), C4H (evm.TU.contig22.251), 4CL (evm.TU.contig7272.385), ANS (evm.TU.contig5828.5), F3'H (evm.TU.contig7272.244), F3′5'H (evm.TU.contig31.16), and F3H (evm.TU.contig4466.49), which have been linked to PA biosynthesis. Yellow module genes included the structural genes PDC (evm.TU.contig4466.583, evm.TU.contig9507.111, evm.TU.contig3684.117) and ADH (evm.TU.contig4397.68, evm.TU.contig2067.296), which have been linked to PA insolubilization. The evm.TU.contig1407.18 (probable aminotransferase ACS10) and evm.TU.contig1077.85 (AHA10) had high interconnections in the brown module and the yellow module, respectively. In addition, the critical transcription factors MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486), bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203), and WD40 (evm.TU.contig1.155) were identified. Among them, the WD40 transcription factor in the yellow module was connected with the PA insolubilization genes ADH and PDC and presented a significant negative correlation with soluble PA content. Combined with the MYB-bHLH-WD40 complex analysis above, WD40 probably interacts with MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203) in the brown module, connecting and coregulating PA biosynthesis and insolubilization in C-PCNA persimmon (Fig. 6b).

Discussion

An overview of genes and transcription factors associated with PA content variation in C-PCNA persimmon fruits at five late stages was obtained using the transcriptome based on a well-annotated C-PCNA persimmon genome. According to previous studies, research on the natural deastringency of the C-PCNA genotype has always been more inclined towards fruit that underwent 40 °C water deastringent treatment21 or the whole development stages as materials38, rather than using fruit at late developmental stages, which is more critical for natural C-PCNA deastringency. In the present study, we analyzed PA content and constructed C-PCNA genotype libraries representing five late development stages and used the transcriptome to evaluate differentially expressed genes and TFs associated with PA variation to identify potential PA biosynthesis-related and insolubilization-related genes.

Comprehensive analysis of phenotype (Fig. 1a), PA content (Fig. 1b), and DEG enrichment (Fig. S2) at five late developmental stages of the C-PCNA persimmon ‘Xiaoguo-tianshi’ helped us pinpoint the critical phase for PA variation. The C-PCNA persimmon fruit experiences the fastest growth stage from 120 to 140 DAF, where the soluble, insoluble, and total PA content was decreased. Moreover, the enrichment of “flavonoid biosynthesis” at this time point was related to PA biosynthesis39. These results indicated that 120–140 DAF could be the critical phase for the “dilution effect”. Soluble PA decreased while insoluble PA levels for C-PCNA persimmon increased rapidly from 140 to 160 DAF. Meanwhile, GO terms such as “drug transmembrane transporter activity” relating to PA transport40 and KEGG term “flavonoid biosynthesis” were significantly enriched. The results showed that 140–160 DAF could be the critical phase for PA transport and the “coagulation effect”. These results are consistent with previous research showing that C-PCNA persimmon undergoes deastringency at the late stage6.

Chorismate acid links primary and secondary metabolism in the shikimate pathway, which refers to the synthesis of phenylalanine from erythrose 4-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate in several steps41. It has been reported previously that inhibiting the DAHPS or DHD/SDH of the shikimate pathway results in the reduction of some secondary metabolites, such as chlorogenate and lignin, in tobacco and potato plants42,43. In our study, it was revealed that 1 DAHPS and 1 DHD/SDH were aggregated in cluster 2 and were downregulated between T4 vs T3 and T5 vs T4, which matched the proanthocyanin content. Downregulation of DHD/SDH has been reported in J-PCNA9, C-PCNA5, and artificially treated PCA persimmon44. However, DAHPS downregulation was observed in C-PCNA and C-PCNA persimmon that underwent artificial 40 °C water treatment21. These results showed that termination of PA accumulation accompanies downregulation of DAHPS and DHD/SDH in persimmon fruit.

Biosynthesis of the PA precursor flavan-3-ols shares the phenylpropane metabolic pathway, flavonoid synthesis and proanthocyanidin pathway9,45. LAR and ANR encode key enzymes involved in PA biosynthesis, which act in the production of 2,3-trans-flavan-3-ols [(+)-catechin (CA), and (+)-gallocatechin (GC)], 2,3-cis-flavan-3-ols [(−)-epicatechin (EC), (−)-epigallocatechin (ECG), and (−)-epi-gallocatechin 3-O-gallate (EGCG)], respectively44. We found that the expression of the phenylpropane and flavonoid structural genes PAL, C4H, 4CL, ANR, ANS, CHS, F3’H, F3′5'H, and F3H decreased at T4 compared to T3, which was consistent with the decreased PA level. However, the LAR gene showed no differential expression in any developmental stage, which caused a reduction in epigallocatechin (EGC) and EGCG. This was one of the main reasons for PA reduction in the PCNA genotype9. Moreover, overexpression of Chinese Bayberry MrANR and MrLAR in tobacco indicated that MrANR increased PA accumulation, while MrLAR was unable to affect the total PA contents46. These results revealed that ANR was highly downregulated at the late stage of persimmon, which might be associated with the decrease in PA content by inhibiting PA precursor biosynthesis.

Previous studies suggest that acetaldehyde metabolism plays an important role in the astringency loss in both C-PCNA genotype21 and PCA persimmon with artificial deastringency treatment47. In plants, pyruvate is converted to acetaldehyde by PDC, then to ethanol by ADH, and acetate by mitochondrial ALDH2a and ALDH2b during the acetaldehyde biosynthesis process48,49. We found that 3 ADH and 2 ALDH genes that grouped in cluster 2 were downregulated, and 2 ADH and 1 ALDH that grouped in cluster 5 were upregulated. Three PDC genes were found to aggregate in cluster 5 and were upregulated between T5 and T4, which matched the insoluble PA content. The ADH-like and ALDH2 genes were downregulated in the C-PCNA genotype natural deastringency process, and PDC2 was specifically upregulated21. However, the expression patterns of the DkADH1,3 and DkPDC1,2 genes were upregulated in PCA persimmon during artificial ethylene deastringency treatment47, and 1 ADH-like gene showed high expression in 40 °C water treatment21. The upregulation of ADH and PDC genes to ethylene was also reported in other fruits, such as apricot50 and melon51, implying that the decrease in ALDH genes and the increase in ADH and PDC genes might result in acetaldehyde accumulation, causing C-PCNA deastringency naturally via PA insolubilization.

PA and anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway genes are mainly regulated by the MBW complex in plants, such as Medicago truncatula52 and Anthurium andraeanum53. MYB transcription factors are core members of the MBW complex. MYB182 overexpression results in the reduction of PA and anthocyanin levels in poplar by reducing the expression of flavonoid biosynthesis structural genes54. DkMYB14 in persimmon acts as both a repressor in PA biosynthesis and an activator in acetaldehyde biosynthesis19. MYB and bHLH autonomously mediate the expression of genes involved in the middle steps of the phenylpropanoid pathway16. In the ‘Red Delicious’, only a few MYB and bHLH members in the fruit skin were significantly correlated with anthocyanin content and suggested to regulate anthocyanin accumulation55. WD40 proteins in the MBW complex are thought to confer a docking platform for the MYB–bHLH interaction56. A member of the MBW protein complex has been identified in persimmon through homologous cloning20 and transcriptome sequencing21. DkMYB2, DkMYB4, and DkMYC1 (MBW) cooperatively increase the expression of a persimmon ANR gene involved in the biosynthesis of PA precursor cis-flavan-3-ols, which not only echoes the above analysis of PA biosynthesis structural genes, but also supports the presence of MBW complexes in persimmon57. We also identified R2R3MYB, bHLH, and WD40 members based on the unpublished C-PCNA persimmon genome and indicated that the expression of the transcription factors R2R3-MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486 and evm.TU.contig7396.13) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203 and evm.TU.contig8910.303) positively correlated with the total PA content and WD40 (evm.TU.contig1.155) negatively correlated with the soluble PA content. These data provide the basis for targeted gene resources of transcription factors involved in PA accumulation in C-PCNA persimmon.

To reveal the potential regulatory network underlying PA content variation in C-PCNA persimmon, we performed WGCNA to identify modules of highly correlated genes associated with soluble PA, insoluble PA, and total PA content. We found that most PA biosynthesis and insolubilization DEGs were included in the brown and yellow modules, which were highly correlated with the soluble, insoluble, and total PA contents of the C-PCNA persimmon. A network of genes that were highly coexpressed with these PA biosynthesis-related and insolubilization-related DEGs was constructed. Among these genes, an MBW complex homologous WD40 gene (evm.TU.contig1.155) showed a high correlation with the PA insolubilization genes ADH and PDC in WGCNA. This WD40 gene also presented a highly negative correlation with soluble PA content. Previous studies have reported that the expression pattern of DkWD40 was consistent with that of PA insolubilization genes such as ADH, and it is also consistent with the transformation of soluble PA to insoluble PA in the “Nishimura-wase” persimmon58. Combining WGCNA and phylogenetic analysis of the MBW complex, we found that the WD40 gene (evm.TU.contig1.155), MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203) might be linked between PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization. In this study, evm.TU.contig1407.18 (probable aminotransferase ACS10) and evm.TU.contig1077.85 (AHA10) were coexpressed with the WD40 gene (evm.TU.contig1.155), MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203) and harbored the highest connections in the brown and yellow modules, respectively. ACS is the key enzyme in the ethylene biosynthetic pathway in plants59. In Arabidopsis, AtACS10 is not ACC synthase but aminotransferase, it was clustered with alanine AT and aspartate AT, which speculated that it might encode aminotransferase60. Complementation experiments showed that AtACS10 and AtACS12 were ATases with broad specificity for aspartic acid and aromatic amino acids such as tyrosine and phenylalanine60. Besides, aspartate AT, the homologous genes of AtACS10, catalyze the synthesis of compounds such as phenylalanine via a transamination reaction61. Phenylalanine is the precursor of many flavonoid compounds such as PA, anthocyanins, and isoflavonoids62. The conversion of phenylalanine to PA and anthocyanins was catalyzed by enzymes such as PAL, C4H, and 4CL63, which is consistent with our results that ACS10 and the genes encoding these enzymes were coexpressed. AHA10 that have been associated with PA accumulation with the disturbance of vacuolar acidification activates TT12 to transport PA into vacuoles64. Thus, evm.TU.contig1407.18 (probable aminotransferase ACS10) and evm.TU.contig1077.85 (AHA10) might play important roles in the regulation of PA accumulation. The overall results suggest that the MBW complex might play important roles in regulating PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization; however, the mechanism remains unclear and requires further investigation.

Conclusion

Transcriptome data of C-PCNA persimmon fruit at five developmental stages have provided the specific processes that lead to PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization. Altogether, the physiological, PA content, and transcriptome data revealed that 120 to 140 DAF is the critical phase for PA biosynthesis, while 140 to 160 DAF is the critical phase for PA transport and PA insolubilization. The results indicate that the downregulation of the ANR gene at T5 vs T4 may be associated with a reduction in PA biosynthesis by inhibiting its precursor cis-flavan-3-ols. The decrease in ALDH and an increase in ADH and PDC genes might result in C-PCNA persimmon’s PA insolubilization. MBW complex homologous R2R3-MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486 and evm.TU.contig7396.13), bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203 and evm.TU.contig8910.303), and WD40 (evm.TU.contig1.155) were isolated from the C-PCNA D.kaki genome (unpublished) and were highly correlated with PA content. In addition, the WD40 (evm.TU.contig1.155), MYB (evm.TU.contig8910.486) and bHLH (evm.TU.contig1398.203) genes might link and coregulate both PA biosynthesis and insolubilization via WGCNA. These genes might play important roles in PA content variation. This study laid an empirical foundation for ongoing investigations of PA biosynthesis and PA insolubilization in C-PCNA persimmon.

Data availability

The raw transcriptome sequencing data were deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Sequence Read Archive (NCBI SRA) under Bioproject ID PRJNA771936.

References

Wang, R., Yang, T. & Ruan, X. Industry history and culture of persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) in China. Acta Hortic. 996, 49–54. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.996.3 (2013).

Yonemori, K., Sugiura, A. & Yamada, M. Persimmon genetics and breeding in plant breeding reviews, Vol. 19 (ed. Janick, J. Ch.) 6, 191–225 (Wiley, 2000).

Sato, A. & Yamada, M. Persimmon breeding in Japan for pollination-constant non-astringent (PCNA) type with marker-assisted selection. Breed Sci. 66, 60–68. https://doi.org/10.1270/jsbbs.66.60 (2016).

Taira, S. Astringency in persimmon in fruit analysis, Vol. 18 (eds Linskens, H. F. et al.) Ch. 6, 97–110 (Springer, 1996).

Ikegami, K. et al. Segregations of astringent progenies in the F1 populations derived from crosses between a Chinese pollination-constant nonastringent (PCNA) ‘Luo Tian Tian Shi’, and Japanese PCNA and pollination-constant astringent (PCA) cultivars of Japanese origin. HortSci. 41, 561. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.41.3.561 (2006).

Zhang, Q., Chen, D. & Luo, Z. Natural astringency loss property of a pollination-constant non-astringent persimmon newly found in central China. Acta Hortic 996, 207–211. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2013.996.28 (2013).

Yonemori, K., Matsushima, J. & Sugiura, A. Differences in tannins of non-astringent and astringent type fruits of Japanese persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.). J. Japanese Soc. Hort. Sci. 52, 135–144 (1983).

Yonemori, K. & Matsushima, J. Property of development of the tannin cells in non-astringent type fruits of Japanese persimmon (Diospyros kaki) and its relationship to natural deastringency. J. Japanese Soc. Hort. Sci. 54, 201–208. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs.54.201 (1985).

Akagi, T. et al. Expression balances of structural genes in shikimate and flavonoid biosynthesis cause a difference in proanthocyanidin accumulation in persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) fruit. Planta 230, 899–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-009-0991-6 (2009).

Lim, I. & Ha, J. Biosynthetic pathway of proanthocyanidins in major cash crops. Plants 10, 1792. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants10091792 (2021).

Taira, S., Ikeda, K. & Ohkawa, K. Comparison of insolubility of tannins induced by acetaldehyde vapor in fruits of three types of astringent persimmon. Nippon Shokuhin Kagaku Kogaku Kaishi 48, 684–687. https://doi.org/10.3136/nskkk.48.684 (2001).

Tanaka, T., Takahashi, R., Kouno, I. & Nonaka, G. I. Chemical evidence for the deastringency (insolubilization of tannins) of persimmon fruit. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1, 3013–3022. https://doi.org/10.1039/P19940003013 (1994).

Mo, R. et al. ADH and PDC genes involved in tannins coagulation leading to natural deastringency in Chinese pollination constant and non-astringency persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.). Tree Genet. 12, 17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-016-0976-0 (2016).

Xu, J. et al. ALDH2 genes are negatively correlated with natural deastringency in Chinese PCNA persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.). Tree Genet. 13, 122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1207-z (2017).

Naik, J., Misra, P., Trivedi, P. K. & Pandey, A. Molecular components associated with the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 317, 111196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2022.111196 (2022).

Baudry, A. et al. TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 39, 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02138.x (2004).

Schaart, J. G. et al. Identification and characterization of MYB-bHLH-WD40 regulatory complexes controlling proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa) fruits. New Phytol. 197, 454–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12017 (2013).

Akagi, T. et al. DkMyb4 Is a Myb transcription factor involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol. 151, 2028–2045. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.109.146985 (2009).

Chen, W. et al. DkMYB14 is a bifunctional transcription factor that regulates the accumulation of proanthocyanidin in persimmon fruit. Plant J. 106, 1708–1727. https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.15266 (2021).

Su, F., Hu, J., Zhang, Q. & Luo, Z. Isolation and characterization of a basic Helix–Loop–Helix transcription factor gene potentially involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis regulation in persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.). Sci. Hortic. 136, 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scienta.2012.01.013 (2012).

Chen, W., Xiong, Y., Xu, L., Zhang, Q. & Luo, Z. An integrated analysis based on transcriptome and proteome reveals deastringency-related genes in CPCNA persimmon. Sci Rep. 7, 44671. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44671 (2017).

Luo, C., Zhang, Q. & Luo, Z. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of Chinese pollination-constant nonastringent persimmon fruit treated with ethanol. BMC Genom. 15, 112 (2014).

Oshida, M., Yonemori, K. & Sugiura, A. On the nature of coagulated tannins in astringent-type persimmon fruit after an artificial treatment of astringency removal. Postharvest Bio. Technol. 8, 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0925-5214(96)00016-6 (1996).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Ashburner, M. et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. The gene ontology consortium. Nat. Genet. 25, 25–29. https://doi.org/10.1038/75556 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S., Okuno, Y. & Hattori, M. The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucl. Acids Res. 32, D277–D280. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkh063 (2004).

Wu, T. et al. ClusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation 2, 100141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141 (2021).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

Otasek, D., Morris, J., Bouças, J., Pico, A. & Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biol. 20, 185. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-019-1758-4 (2019).

Du, G. et al. Selection and validation of reference genes for quantitative gene expression analyses in persimmon (Diospyros kaki Thunb.) using real-time quantitative PCR. Biologia Futura 70, 261–267. https://doi.org/10.1556/019.70.2019.24 (2019).

Baudry, A., Caboche, M. & Lepiniec, L. TT8 controls its own expression in a feedback regulation involving TTG1 and homologous MYB and bHLH factors, allowing a strong and cell-specific accumulation of flavonoids in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 46, 768–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02733.x (2006).

An, X., Tian, Y., Chen, K., Wang, X. & Hao, Y. The apple WD40 protein MdTTG1 interacts with bHLH but not MYB proteins to regulate anthocyanin accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 710–717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2012.01.015 (2012).

Terrier, N. et al. Ectopic expression of VvMybPA2 promotes proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in grapevine and suggests additional targets in the pathway. Plant Physiol. 149, 1028–1041. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.131862 (2009).

Deluc, L. et al. The transcription factor VvMYB5b contributes to the regulation of anthocyanin and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in developing grape berries. Plant Physiol. 147, 2041–2053. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.118919 (2008).

Deluc, L. et al. Characterization of a grapevine R2R3-MYB transcription factor that regulates the phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Physiol. 140, 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.105.067231 (2006).

Larkin, M. A. et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404 (2007).

Tamura, K. et al. MEGA5: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msr121 (2011).

Zheng, Q. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals regulatory network and regulators associated with proanthocyanidin accumulation in persimmon. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 356. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03133-z (2021).

Wasternack, C. & Strnad, M. Jasmonates are signals in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites pathways, transcription factors and applied aspects–a brief review. New Biotechnol. 48, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbt.2017.09.007 (2019).

Xu, L. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of upland cotton MATE gene family reveals a conserved subfamily involved in transport of proanthocyanidins. Mol. Biol. Rep. 46, 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-018-4457-4 (2019).

Herrmann, K. M. & Weaver, L. M. The shikimate pathway. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 50, 473–503. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.473 (1999).

Jones, J., Henstrand, J., Handa, A. & Weller, H. Impaired wound induction of 3-deoxy-d-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate (DAHP) synthase and altered stem development in transgenic potato plants expressing a DAHP synthase antisense construct. Plant Physiol. 108, 1413–1421. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.4.1413 (1995).

Ding, L. et al. Functional analysis of the essential bifunctional tobacco enzyme 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase in transgenic tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 2053–2067. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/erm059 (2007).

Ikegami, A., Eguchi, S., Kitajima, A., Inoue, K. & Yonemori, K. Identification of genes involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis of persimmon (Diospyros kaki) fruit. Plant Sci. 172, 1037–1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.02.010 (2007).

Xiao, Y. et al. Transcriptome and biochemical analyses revealed a detailed proanthocyanidin biosynthesis pathway in brown cotton fiber. PLoS ONE 9, e86344. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0086344 (2014).

Shi, L. et al. Proanthocyanidin synthesis in Chinese Bayberry (Myrica rubra Sieb. et Zucc.) fruits. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00212 (2018).

Min, T. et al. Ethylene-responsive transcription factors interact with promoters of ADH and PDC involved in persimmon (Diospyros kaki) fruit de-astringency. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 6393–6405. https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers296 (2012).

Strommer, J. The plant ADH gene family. Plant J. 66, 128–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04458.x (2011).

Luo, C., Zhang, Q. & Luo, Z. Genome-wide transcriptome analysis of Chinese pollination-constant nonastringent persimmon fruit treated with ethanol. BMC Genom. 15, 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-112 (2014).

González-Agüero, M. et al. Differential expression levels of aroma-related genes during ripening of apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 47, 435–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2009.01.002 (2009).

Manríquez, D. et al. Two highly divergent alcohol dehydrogenases of melon exhibit fruit ripening-specific expression and distinct biochemical characteristics. Plant Mol. Biol. 61, 675. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-006-0040-9 (2006).

Jun, J. H., Liu, C., Xiao, X. & Dixon, R. A. The transcriptional repressor MYB2 regulates both spatial and temporal patterns of proanthocyandin and anthocyanin pigmentation in Medicago truncatula. Plant Cell 27, 2860–2879. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.15.00476 (2015).

Li, C., Qiu, J., Huang, S., Yin, J. & Yang, G. AaMYB3 interacts with AabHLH1 to regulate proanthocyanidin accumulation in Anthurium andraeanum (Hort.)—another strategy to modulate pigmentation. Hort. Res. 6, 14. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41438-018-0102-6 (2019).

Yoshida, K., Ma, D. & Constabel, C. P. Thes MYB182 protein down-regulates proanthocyanidin and anthocyanin biosynthesis in poplar by repressing both structural and regulatory flavonoid genes. Plant Physiol. 167, 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.114.253674 (2015).

Li, W. et al. Anthocyanin accumulation correlates with hormones in the fruit skin of “Red Delicious” and its four generation bud sport mutants. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 363. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-018-1595-8 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of the accumulation of anthocyanins revealed the underlying metabolic and molecular mechanisms of purple pod coloration in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.). Foods 10, 2180. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10092180 (2021).

Gil-Muñoz, F. et al. MBW complexes impinge on anthocyanidin reductase gene regulation for proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Sci. Rep. 10, 3543. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60635-w (2020).

Su, F. Isolation and characterization of MYB, basic Helix-Loop-Helix and WD40 transcription factors genes involved in persimmon proanthocyanidin metabolism, Huazhong Agricultural University, (2012).

Pattyn, J., Vaughan-Hirsch, J. & Van de Poel, B. The regulation of ethylene biosynthesis: A complex multilevel control circuitry. New Phytol. 229, 770–782. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.16873 (2021).

Yamagami, T. et al. Biochemical diversity among the 1-Amino-cyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase isozymes encoded by the Arabidopsis gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 49102–49112. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M308297200 (2003).

Dornfeld, C. et al. Phylobiochemical characterization of class-Ib aspartate/prephenate aminotransferases reveals evolution of the plant arogenate phenylalanine pathway. Plant Cell 26, 3101–3114. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.114.127407 (2014).

Xi, D. et al. The combined analysis of transcriptome and metabolome provides insights into purple leaves in Eruca vesicaria subsp. Sativa. Agronomy 12, 2046. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12092046 (2022).

Dixon, R., Liu, C. & Jun, J. Metabolic engineering of anthocyanins and condensed tannins in plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 24, 329–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2012.07.004 (2012).

Baxter, I. et al. A plasma membrane H+-ATPase is required for the formation of proanthocyanidins in the seed coat endothelium of Arabidopsis thaliana. PNAS 102, 2649–2564. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0406377102 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFD1001200) and the Central Non-profit Research Institution of CAF in China (CAFYBB2019MA005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W., Q.Z., and T.P. carried out the experiments and participated in the data analysis; W.H., S.D., H.L., and P.S. participated in the sampling and investigation; J.F. and Y.S. conceived and designed the experiments and helped draft and review the manuscript. All authors contributed to the critical review and editing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Zhang, Q., Pu, T. et al. Transcriptomic profiling analysis to identify genes associated with PA biosynthesis and insolubilization in the late stage of fruit development in C-PCNA persimmon. Sci Rep 12, 19140 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23742-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-23742-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.