Abstract

Evidence of the role of cooking methods on inflammation and metabolic health is scarce due to the paucity of large-size studies. Our aim was to evaluate the association of cooking methods with inflammatory markers, renal function, and other hormones and nutritional biomarkers in a general population of older adults. In a cross sectional analysis with 2467 individuals aged ≥ 65, dietary and cooking information was collected using a validated face-to-face dietary history. Eight cooking methods were considered: raw, boiling, roasting, pan-frying, frying, toasting, sautéing, and stewing. Biomarkers were analyzed in a central laboratory following standard procedures. Marginal effects from generalized linear models were calculated and percentage differences (PD) of the multivariable-adjusted means of biomarkers between extreme sex-specific quintiles (Q) of cooking methods consumption were computed ([Q5 − Q1/Q1] × 100). Participants’ mean age was 71.6 years (53% women). Significant PD for the highest vs lowest quintile of raw food consumption was − 54.7% for high sensitivity-C reactive protein (hs-CRP), − 11.9% for neutrophils, − 11.9% for Growth Differentiation Factor-15, − 25.0% for Interleukin-6 (IL-6), − 12.3% for urinary albumin, and − 10.3% for uric acid. PD for boiling were − 17.8% for hs-CRP, − 12.4% for urinary albumin, and − 11.3% for thyroid-stimulating hormone. Concerning pan-frying, the PD was − 23.2% for hs-CRP, − 11.5% for IL-6, − 16.3% for urinary albumin and 10.9% for serum vitamin D. For frying, the PD was a 25.7% for hs-CRP, and − 12.6% for vitamin D. For toasting, corresponding figures were − 21.4% for hs-CRP, − 11.1% for IL-6 and 10.6% for vitamin D. For stewing, the PD was 13.3% for hs-CRP. Raw, boiling, pan-frying, and toasting were associated with healthy profiles as for inflammatory markers, renal function, thyroid hormones, and serum vitamin D. On the contrary, frying and, to a less extent, stewing showed unhealthier profiles. Cooking methods not including added fats where healthier than those with added fats heated at high temperatures or during longer periods of time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Classical nutritional epidemiology has mostly studied the role of foods, food groups, nutrients and energy intake as well as dietary patterns on the prevention and management of chronic diseases1,2. However, food preparation, including cooking methods, have only recently received attention.

Indeed, the study of cooking methods has been very limited. One of the main reasons is the lack of data on cooking methods in large-sized studies, particularly when diet is collected using food frequency questionnaires. Besides, information on cooking was usually obtained in small studies focusing on changes in nutrient composition and physicochemical quality when a limited number of foods were subjected to different types of cooking3,4.

Frying is the most frequently studied cooking method in large populations, both in the United States and in Spain. In the United States, analyses from the Nurses' Health Study and the Health Professionals Follow-Up Study showed an association between fried food consumption and higher incident diabetes, cardiovascular disease and heart failure5,6. Similar results were obtained in a large sample of American veterans7. However, in Spain no association was found between the consumption of fried food and incident cardiovascular disease8,9. Other cooking methods have scarcely been investigated10.

Nevertheless, the study of cooking methods could provide interesting insights into the investigation of chronic diseases development given that many of these are related to changes in inflammatory, renal, and other nutritional biomarkers11,12. Thus, in a previous large-sized study, cooking patterns showed a relationship with inflammatory and cardio-metabolic health biomarkers13. More specifically, four cooking patterns were found: (a) The “Spanish traditional pattern”, characterized by boiling, sautéing, brining, and pan-frying, tended to be metabolically advantageous; (b) the “Health-conscious pattern”, based on battering, frying, and stewing, seemed to improve renal function; (c) the “Youth-style pattern”, with frequent consumption of soft drinks and distilled alcoholic drinks, and low consumption of raw food, was associated with metabolic benefits, except for a higher insulin and higher urinary albumin levels; and (d) the “Social business pattern”, rich in fermented alcoholic drinks, food cured with salt or smoked, and cured cheese, appeared to be detrimental for lipid profile, renal function and other metabolic biomarkers.

Therefore, the aim of the study was to evaluate for the first time in literature, the association of eight cooking methods with a wide array of inflammatory, renal, and other hormones and nutritional biomarkers in a population-based sample of older adults. In this population, these parameters have been little examined, and might reflect their metabolic and renal health profiles. Our initial hypothesis was that frying could be a detrimental form of cooking, while boiling, pan-frying, and sautéing could be beneficial cooking methods.

Methods

Study design and participants

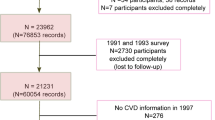

The Seniors-ENRICA-2 study consists of 3273 individuals aged 65 years and older. Analyses were performed with baseline information of this cohort including those recruited from 2015 to 2017. Participants came from community-dwelling population of Community of Madrid (Spain) that included its capital, Madrid, and another four surrounding municipalities with large populations: Alcalá de Henares, Alcorcón, Getafe, and Torrejón de Ardoz. Participants were selected among those with a national health care card and following a sex- and district-stratified random sampling. Of note is that access to the health care system is universal in Spain.

Information was obtained in three stages, with similar procedures to the Seniors-ENRICA-1 study14. Sociodemographic and lifestyle characteristics, morbidity, and healthcare use were obtained by a telephone interview. Then, blood and urine sample collections along with a physical examination were performed in a home visit. Seven days later an interviewer performed a face-to-face dietary history.

From the initial sample of 3273 participants, a total of 806 were excluded: 483 (14.8%) without dietary information, 12 (0.4%) with implausible values for total energy intake (< 800 kcal/day or > 5.000 kcal/day in men; < 500 kcal/day or > 4.000 kcal/day in women), 20 (0.6%) lacking data on potential confounders, and 291 (8.9%) with missing information on laboratory biomarkers. Therefore, 2467 participants remained for main analyses; a nested subsample was used to analyze some biomarkers as described in Biomarkers section below.

All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All participants gave written informed consent. The Clinical Research Ethics Committee of La Paz University Hospital in Madrid provided ethics approval.

Dietary information and cooking methods

Information on cooking methods was collected by trained and certified non-medical interviewers through a validated dietary history, DH-ENRICA. Information on habitual food consumption was collected considering all food consumed at least once every two weeks during the year prior to the interview. DH-ENRICA comprises 860 foods along with their cooking technique or preservation method. To estimate portion sizes, 127 sets of digitalized photos, household measurements and information on food proportion of typical ingredients from Spanish recipes were used15. Then, food consumption according to their cooking method was summed up in grams per day.

Eight cooking methods with a minimum mean consumption of 15 g/d were included in this analysis: raw (not cooked), boiling (cooking in aqueous medium with heat transmission by water), roasting (dry cooking transmitted by air or radiation), pan-frying (high temperature dry cooking using a pan and a minimum amount of oil), frying (high temperature cooking with food immersed in hot fats or oils; breaded, floured or battered food were also considered in this category), toasting (browning food using heat radiation), sautéing (brief medium to high heat cooking in a low-fat pan), and stewing (low heat cooking, usually simmered food in liquids for a long period of time). Mixed cooking methods (e.g. boiling + sautéing, frying + boiling, or sautéing + roasting) were not considered for this analysis since these are not frequent in Mediterranean diet16,17 and were barely consumed by participants in this study (less than 10 g per day).

Biomarkers

At first home visit, 12-h fasting blood and urine samples were collected by nurses using standardized procedures. Inflammation markers were measured, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP), white blood cell count (WBC), neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, growth differentiation factor-15 (GDF-15) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Renal function was assessed with serum creatinine, urinary albumin, serum uric acid, serum sodium, and serum potassium. Chronic Kidney Disease-Epidemiology Collaboration equation (CKD-EPI) was used to assess glomerular filtration rate based on serum creatinine levels18. Hormones and other nutritional biomarkers included thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), serum vitamin D, serum albumin, and total serum protein. A description of biomarkers measurement scales and procedures is provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Some measurements were only determined in a 1066 participants subsample, corresponding to those recruited from January 1st, 2017 to the end of the study. These biomarkers encompassed: hs-CRP, urinary albumin, serum uric acid, serum sodium, serum potassium, TSH, serum vitamin D, and serum albumin. All samples were centrally analyzed in core laboratory at La Paz University Hospital in Madrid.

Potential confounders

Participants provided information on age, sex, educational level (primary or less, secondary, university), smoking status (current, former or never smoker). Alcohol consumption was assessed using the dietary history. A specific question was answered to ascertain former-drinker status. Recreational physical activity and household physical activity was evaluated with the EPIC short physical activity questionnaire with 17 items. Each of them was multiplied by their respective energy expenditure rate in metabolic equivalent of task—METs·hour/week19 and total energy expenditure was calculated by summing up all physical activities. Number of television hours was used as sedentary lifestyle indicator. To assess morbidity, the number of chronic diseases and the number of medications prescribed (checked against packaging) were considered. To take into account diet quality and its influence in the results, models were also adjusted for the intake of very long chain omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid—EPA, and docosahexaenoic acid—DHA), and for total fiber consumption.

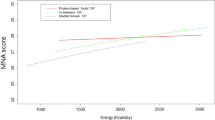

Statistical analysis

For each cooking method, analyses were performed in grams per kilogram (g/kg) of body weight to take into account body size. Participants were classified into sex-specific quintiles for each cooking method. Data on biomarkers were log-transformed in order to achieve normality. Marginal effects from generalized linear model (GLM) were obtained. The regression models were adjusted for sex, age, energy intake, educational level, smoking, alcohol consumption, former-drinker status, recreational physical activity in METs·hours/week, household physical activity in METs·hours/week, hours of television hours, number of chronic diseases, number of prescribed medications, intake of very long chain omega-3 fatty acids (eicosapentaenoic acid—EPA, and docosahexaenoic acid—DHA), and total fiber consumption. Geometric means were estimated, and percentage differences (PD) were calculated as [(5th quintile–1st quintile)/1st quintile] × 100. In this study, a PD greater than 10% was deemed clinically relevant. A similar cut-off point has been considered clinically relevant in other scenarios (such as in hypertension) when using nutritional recommendations for medical chronic conditions20. To calculate p for linear trend, quintiles of consumption were modelled as a continuous variable.

All analyses were performed with Stata, version 15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA), setting the statistical significance at p < 0.05.

Results

The main analyses were performed with 2467 participants with a mean age of 71.6 (± 4.4) years, and 53.0% were women. Those collected after January 1st, 2017 (subsample, n = 1066) had a mean age of 70.8 (± 3.9) years, and 49% were women. Baseline characteristics of main sample according to quintiles of cooking methods are shown in Table 1. Significant differences were found when comparing extreme quintiles of consumption for each cooking method. In general, those in the highest quintile of consumption of raw and pan-frying had the healthiest lifestyle profile. However, those in the highest quintile of consumption of roasting, frying, and stewing showed a more harmful lifestyle profile.

PD of inflammatory factors, renal function, and other hormone and nutritional biomarkers are provided in Table 2. A mean of 470 (± 208) g/d of raw food was consumed. PD for raw food consumption was − 54.7% for hs-CRP, − 11.9% for neutrophils, − 11.9% for GDF-15, − 25.0% for IL-6, − 12.3% for urinary albumin, and − 10.3% for uric acid. Considering boiling, a mean of 277 (± 119) g/d was consumed. PD for boiling was − 17.8% for hs-CRP, − 12.4% for urinary albumin, and − 11.3% for TSH. Concerning roasting, a mean of 156 (± 68) g/d was consumed. No relevant PD were found for roasting, although a trend towards lower urinary albumin and uric acid was observed. A mean of 63 (± 47) g/d of pan-frying food was consumed. PD for pan-frying were − 23.2% for hs-CRP, − 11.5% for IL-6, − 16.3% for urinary albumin, and showed an increase of 10.9% for serum vitamin D. A mean of 42 (± 33) g/d of frying food was consumed. PD for frying were 25.7 for hs-CPR and − 12.6 for vitamin D. Observing toasting, 42 (± 40) g/d was consumed. PD for toasting were − 21.4% for hs-CRP, and − 11.1% for IL-6. Also, a PD of 10.6% in serum vitamin D was observed. Regarding sautéing, a mean of 22 (± 21) g/d was consumed. No differences were observed between extreme quintiles for sautéing consumption. A mean of 19 (± 21) g/d of stewing food was consumed. PD for stewing was of 13.3% for hs-CRP. Adjusted means (95% confidence interval), percentage difference, and p for linear trend across quintiles of cooking methods consumption are presented in Supplementary Tables 2–9.

Discussion

In this large population-based study on cooking methods, raw, boiling, pan-frying, and toasting showed beneficial profiles for inflammatory markers, while frying and stewing showed detrimental inflammatory profiles. Raw, boiling, and pan-frying showed beneficial differences in renal biomarkers; no other cooking methods influenced renal function. Boiling was associated with lower TSH levels. Pan-frying and toasting were associated with a higher serum vitamin D, while frying was associated with a lower level of this vitamin. Therefore, raw, boiling, pan-frying, and toasting are associated with healthy profiles. However, frying and, to a less extent, stewing showed unhealthier profiles. Cooking methods that included no added fats where healthier than those including added fats heated at high temperatures or during longer periods of time.

Our results, obtained in a sample of older adults, are an example of novel exposures influence that have hardly been studied in the past and that may also be used as a healthy ageing strategy21. Thus, although some cooking methods are considered healthy, and in many cases older adults have gradually adopted them, comprehensive information that provides guidance on food preparation has never been provided in literature before.

Several mechanisms could alter food while it is being processed, including thermal procedures and the addition of certain components such as fats. For instance, mechanical processing or soaking could also modify nutrient bioavailability22. Then, there is a wide range of processes involved: from liquid evaporation and its substitution with fats23,24, variations on antioxidant activity25,26, formation of advanced glycation end products27,28, to altered glycemic and insulinemic responses29,30. In addition, some specific cooking methods are considered harmful. During deep-frying, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic amines are produced, which are genotoxic agents, and have been associated with cancer incidence31. Also, saturated fatty acids formation could increase during frying32 that, depending on its food source, are related varied biological effects.

Our findings support that, among the elderly, raw food consumption is associated with beneficial marker profiles (such as lower levels of hs-CRP, neutrophils, GDF-15, IL-6, urinary albumin, and serum uric acid). Two cross-sectional studies assessed the consumption of raw food-only diets. The first concluded that such a diet was associated with weight reduction, but also with underweight33. In the second one, an exclusive raw food diet was associated with lower LDL-cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol levels, in addition to vitamin B-12 deficiency34. Hence, along with general recommendations for a healthy diet (quality food choices and adequate daily consumption), it seems very reasonable to favor raw food consumption for this age group.

Regarding inflammatory markers, raw, boiling, and toasting food consumption were associated with lower hs-CRP levels. A possible explanation could rely on the fact that these cooking methods usually do not imply the addition of unhealthy fat sources35. In an analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) conducted with 4900 adults, it was observed that saturated fat consumption was modestly associated with elevated hs-CRP36. In addition, raw food has high fiber and antioxidants contents, which are also associated with lower levels of hs-CRP37. On the contrary, frying and stewing were associated with higher hs-CRP levels in this study. The addition of harmful fats or a longer cooking time might be associated with higher levels of this inflammatory marker. Regarding this latter, recent studies have found that a longer cooking time—such in stewing, increases fat content of food38,39 that could lead to deleterious effects on health40.

Concerning other inflammatory markers, the association of raw food consumption (mainly fruit and vegetables) with lower counts of white blood cells and neutrophils was also examined in other studies. An observational study with 51 vegan participants found a reduction in CD4, CD8 and natural-killer cells41. Likewise, Mediterranean diet adherence, rich in raw food, was associated with lower leukocyte count levels42. This is important since neutrophils regulate inflammatory function and it has been suggested that lower neutrophil levels are associated with lower atherothrombotic processes and cardiovascular diseases43,44.

In our study, raw food consumption was also associated with lower GDF-15 levels. Among older adults, the importance of GDF-15 relies on its role as biomarker for cardiac fibrosis45 as well as a marker for chronic disease burden46. An essential cofactor of this biomarker is selenium—mostly found in raw consumed food46, and it has been described an inverse relationship between them47. On the other hand, although cooking methods were not evaluated, a 6-month clinical trial found no association between GDF-15 levels and plant-based or protein-based diets48.

Raw and toasting food consumption showed decreasing differences in IL-6 levels. These cooking methods involve dressing oils and hidden fats from fruits, nuts and seeds (usually consumed toasted)49 which in turn promote carotenoid absorption. Carotenoid levels are inversely related to serum IL-6 due to modifications in systemic inflammatory responses50,51. Similarly, in a cohort with 3075 older adults an association was found between lower IL-6 levels and a dietary pattern that included high consumption of fruit, vegetables, whole grains, and non-fried poultry52. Lower levels of IL-6 might be beneficial as an inverse relationship with coronary heart disease has been observed53.

Concerning renal function, there was a lower mean urinary albumin with raw, boiling, and pan-frying consumption in this population. A high renal excretion of albumin could reflect greater animal protein and fat intake, and, generally, these cooking methods do not involve the addition of fats. Therefore, these could be beneficial for both overweight and high blood pressure prevention54, and might also be recommended in patients with hypertension or decline in renal function. On the other hand, lower uric acid levels occurred with raw food consumption. This is in line with the literature as a lower purine content in raw food could be responsible for a lower uric acid formation55,56.

In relation to hormones and other nutritional biomarkers, our results suggest that boiling is associated with lower TSH levels and it could potentially prevent subclinical hypothyroidism. Though, further research is still needed. A study demonstrated that boiled cauliflower had lower levels of progoitrin, a precursor of goitrin57. However, other boiled cyanogenic plants (cabbage, radish, cassava) have shown high anti-thyroid peroxidase levels that could exert opposite effects58. Additionally, beneficial PD in serum vitamin D was observed with pan-frying and toasting. Conversely, the exposure to high temperatures has been shown to cause adverse effects in vitamin D3 content in food, but knowledge regarding this matter is limited, and the stability of vitamin D3 in added vegetable oils during cooking has not yet been determined59,60. Of note is that for pan-frying and toasting, food is exposed to heat for shorter periods of time.

The main strength of this study is the use of a dietary history that allowed to collect detailed information on food consumption and cooking methods. Its validity and reproducibility has been shown in Spanish population. Standardized procedures have been followed during analytical processing of biological samples in a central laboratory. Likewise, several confounding factors were taken into account (including socio-demographic determinants and lifestyle), although some degree of residual confounding cannot be ruled out.

This study has several limitations that have to be considered. First, since this study has a cross-sectional design, the results cannot establish causality. Second, as when a specific food is studied, it is not possible to distinguish the effect of cooking from the consumption of the food itself. Similarly, we cannot distinguish the effect of a specific cooking method from the effect of added fats when occurring together. Finally, because of administrative reasons, some measurements were only conducted in the subsample recruited from January, 2017 to the end of the study resulting in a reduction in sample size, but without deriving in selection bias.

Conclusions

This study suggests that among older Spanish adults, some cooking methods, especially, raw, boiling, pan-frying, and toasting, are associated with positive differences in several inflammatory markers, renal function, thyroid hormones, and serum vitamin D. Therefore, these findings add information to current knowledge on the possible impact of cooking methods on health. Further studies are needed to establish causality and to fully understand the mechanisms underlying the relationships found.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Brandhorst, S. & Longo, V. D. Dietary restrictions and nutrition in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 124, 952–965 (2019).

Schulze, M. B., Martínez-González, M. A., Fung, T. T., Lichtenstein, A. H. & Forouhi, N. G. Food based dietary patterns and chronic disease prevention. BMJ 361, k2396 (2018).

Bastías, J. M., Balladares, P., Acuña, S., Quevedo, R. & Muñoz, O. Determining the effect of different cooking methods on the nutritional composition of salmon (Salmo salar) and chilean jack mackerel (Trachurus murphyi) fillets. PLoS ONE 12, e0180993 (2017).

Scherr, C. & Ribeiro, J. P. The influence of food preparation methods on atherosclerosis prevention. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 59, 148–154 (2013).

Djoussé, L., Petrone, A. B. & Michael Gaziano, J. Consumption of fried foods and risk of heart failure in the physicians’ health study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 4, e001740 (2015).

Cahill, L. E. et al. Fried-food consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease: A prospective study in 2 cohorts of US women and men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 100, 667–675 (2014).

Honerlaw, J. P. et al. Fried food consumption and risk of coronary artery disease: The Million Veteran Program. Clin. Nutr. 39, 1203–1208 (2020).

Rey-García, J. et al. Fried-food consumption does not increase the risk of stroke in the Spanish cohort of the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) study. J. Nutr. 150, 3241–3248 (2020).

Guallar-Castillón, P. et al. Consumption of fried foods and risk of coronary heart disease: Spanish cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study. BMJ 344, e363 (2012).

Mozaffarian, D., Gottdiener, J. S. & Siscovick, D. S. Intake of tuna or other broiled or baked fish versus fried fish and cardiac structure, function, and hemodynamics. Am. J. Cardiol. 97, 216–222 (2006).

Eimery, S. et al. Association between dietary patterns with kidney function and serum highly sensitive C-reactive protein in Tehranian elderly: An observational study. J. Res. Med. Sci. 25, 19 (2020).

Wang, J. et al. Dietary intake and cardiometabolic biomarkers in relation to insulin resistance and hypertension in a middle-aged and elderly population in Beijing, China. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 42, 869–875 (2017).

Moreno-Franco, B. et al. Association of cooking patterns with inflammatory and cardio-metabolic risk biomarkers. Nutrients 13, 1–14 (2021).

Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. et al. Rationale and methods of the study on nutrition and cardiovascular risk in Spain (ENRICA). Rev. Española Cardiol. (English Ed.) 64, 876–882 (2011).

Guallar-Castillón, P. et al. Validity and reproducibility of a Spanish dietary history. PLoS ONE 9, e86074 (2014).

León-Muñoz, L. M. et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet pattern has declined in Spanish adults. J. Nutr. 142, 1843–1850 (2012).

Garcimartín, A. et al. Frying a cultural way of cooking in the Mediterranean diet and how to obtain improved fried foods. In The Mediterranean Diet 191–207 (Academic Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-818649-7.00019-9.

Levey, A. S. et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 150, 604–612 (2009).

Ainsworth, B. E. et al. 2011 compendium of physical activities: A second update of codes and MET values. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 43, 1575–1581 (2011).

Steinberg, D., Bennett, G. G. & Svetkey, L. The DASH diet, 20 years later. JAMA 317, 1529–1530 (2017).

Harmell, A. L., Jeste, D. & Depp, C. Strategies for successful aging: A research update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 16, 476–482 (2014).

Hotz, C. & Gibson, R. Traditional food-processing and preparation practices to enhance the bioavailability of micronutrients in plant-based diets. J. Nutr. 137, 1097–1100 (2007).

Bouaziz, F. et al. Feasibility of using almond gum as coating agent to improve the quality of fried potato chips: Evaluation of sensorial properties. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 65, 800–807 (2016).

Osawa, C. C. & Gonçalves, L. A. G. Changes in breaded chicken and oil degradation during discontinuous frying with cottonseed oil. Cienc. e Tecnol. Aliment. 32, 692–700 (2012).

Ilyasoʇlu, H. & Burnaz, N. A. Effect of domestic cooking methods on antioxidant capacity of fresh and frozen kale. Int. J. Food Prop. https://doi.org/10.1080/10942912.2014.91931718,1298-1305 (2015).

Jiménez-Monreal, A. M., García-Diz, L., Martínez-Tomé, M., Mariscal, M. & Murcia, M. A. Influence of cooking methods on antioxidant activity of vegetables. J. Food Sci. 74, 97–103 (2009).

Yang, Y., Wang, Z. & Yin, M. Content of nitric oxide and glycative compounds in cured meat products-Negative impact upon health. Biomedicine 8, 28–33 (2018).

DeChristopher, L. R. Perspective: The paradox in dietary advanced glycation end products research: The source of the serum and urinary advanced glycation end products is the intestines, not the food. Adv. Nutr. An Int. Rev. J. 8, 679–683 (2017).

Hodges, C. et al. Method of food preparation influences blood glucose response to a high-carbohydrate meal: A randomised cross-over trial. Foods 9, 23–31 (2019).

Sonia, S., Witjaksono, F. & Ridwan, R. Effect of cooling of cooked white rice on resistant starch content and glycemic response. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 24, 620–625 (2015).

Bulanda, S. & Janoszka, B. Consumption of thermally processed meat containing carcinogenic compounds (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and heterocyclic aromatic amines) versus a risk of some cancers in humans and the possibility of reducing their formation by natural food additives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 4781–4804 (2022).

Mekonnen, M. F., Desta, D. T., Alemayehu, F. R., Kelikay, G. N. & Daba, A. K. Evaluation of fatty acid-related nutritional quality indices in fried and raw nile tilapia, (Oreochromis Niloticus), fish muscles. Food Sci. Nutr. 8, 4814–4821 (2020).

Koebnick, C., Strassner, C., Hoffmann, I. & Leitzmann, C. Consequences of a long-term raw food diet on body weight and menstruation: Results of a questionnaire survey. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 43, 69–79 (1999).

Koebnick, C. et al. Long-term consumption of a raw food diet is associated with favorable serum LDL cholesterol and triglycerides but also with elevated plasma homocysteine and low serum HDL cholesterol in humans. J. Nutr. 135, 2372–2378 (2005).

King, D. E., Egan, B. M. & Geesey, M. E. Relation of dietary fat and fiber to elevation of C-reactive protein. Am. J. Cardiol. 92, 1335–1339 (2003).

Tierney, A. C., Rumble, C. E., Billings, L. M. & George, E. S. Effect of dietary and supplemental lycopene on cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Adv. Nutr. 11, 1453–1488 (2020).

Hosseini, B. et al. Effects of fruit and vegetable consumption on inflammatory biomarkers and immune cell populations: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 108, 136–155 (2018).

Xu, Y. et al. Effect of stewing time on fatty acid composition, textural properties and microstructure of porcine subcutaneous fat from various anatomical locations. J. Food Compos. Anal. 105, 104240 (2022).

Zhu, W. et al. Effects of dietary pork fat cooked using different methods on glucose and lipid metabolism, liver inflammation and gut microbiota in rats. Foods 10, 20 (2021).

Alessandrini, R. et al. Potential impact of gradual reduction of fat content in manufactured and out-of-home food on obesity in the United Kingdom: A modeling study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 1312–1321 (2021).

Link, L. B., Hussaini, N. S. & Jacobson, J. S. Change in quality of life and immune markers after a stay at a raw vegan institute: A pilot study. Complement. Ther. Med. 16, 124–130 (2008).

Bonaccio, M. et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with lower platelet and leukocyte counts: Results from the Moli-sani study. Blood 123, 3037–3044 (2014).

Silvestre-Roig, C., Braster, Q., Ortega-Gomez, A. & Soehnlein, O. Neutrophils as regulators of cardiovascular inflammation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 327–340 (2020).

Gaul, D., Stein, S. & Matter, C. Neutrophils in cardiovascular disease. Eur. Heart J. 38, 1702–1704 (2017).

Alehagen, U. et al. Less fibrosis in elderly subjects supplemented with selenium and coenzyme Q10-A mechanism behind reduced cardiovascular mortality?. BioFactors 44, 137–147 (2018).

Daniels, L. B., Clopton, P., Laughlin, G. A., Maisel, A. S. & Barrett-Connor, E. Growth-differentiation factor-15 is a robust, independent predictor of 11-year mortality risk in community-dwelling older adults: The Rancho Bernardo study. Circulation 123, 2101–2110 (2011).

Prystupa, A. et al. Association between serum selenium concentrations and levels of proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines—interleukin-6 and growth differentiation factor-15, in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 437–446 (2017).

Markova, M. et al. Effects of plant and animal high protein diets on immune-inflammatory biomarkers: A 6-week intervention trial. Clin. Nutr. 39, 862–869 (2020).

Garcia, A. L. et al. Long-term strict raw food diet is associated with favourable plasma β-carotene and low plasma lycopene concentrations in Germans. Br. J. Nutr. 99, 1293–1300 (2008).

Chung, R. W. S., Lundberg, A. K. & Jonasson, L. Lutein exerts anti-inflammatory effects in patients with coronary artery disease Lutein exerts anti-inflammatory effects in patients with coronary artery. Atherosclerosis 262, 87–93 (2017).

Hajizadeh-Sharafabad, F., Zahabi, E. S., Malekahmadi, M., Zarrin, R. & Alizadeh, M. Carotenoids supplementation and inflammation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 1, 1–17 (2021).

Anderson, A. L. et al. Dietary patterns, insulin sensitivity and inflammation in older adults. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 66, 18–24 (2012).

Yuan, S., Lin, A., He, Q., Burgess, S. & Larsson, S. C. Circulating interleukins in relation to coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation and ischemic stroke and its subtypes: A two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Int. J. Cardiol. 313, 99–104 (2020).

Chalwe, J. M., Mukherjee, U., Grobler, C., Mbambara, S. H. & Oldewage-Theron, W. Association between hypertension, obesity and dietary intake in post-menopausal women from rural Zambian communities. Heal. SA Gesondheid 26, 1496–1553 (2021).

Schmidt, J. A., Crowe, F. L., Appleby, P. N., Key, T. J. & Travis, R. C. Serum uric acid concentrations in meat eaters, fish eaters, vegetarians and vegans: A cross-sectional analysis in the EPIC-Oxford cohort. PLoS ONE 8, e56339 (2013).

Chiu, T. H. T., Liu, C. H., Chang, C. C., Lin, M. N. & Lin, C. L. Vegetarian diet and risk of gout in two separate prospective cohort studies. Clin. Nutr. 39, 837–844 (2020).

Hwang, E.-S. Effect of cooking method on antioxidant compound contents in cauliflower. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci 24, 210–216 (2019).

Leko, M. B., Gunjača, I., Pleić, N. & Zemunik, T. Environmental factors affecting thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroid hormone levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 6521–6583 (2021).

Tabibian, M. et al. Evaluation of vitamin D3 and D2 stability in fortified flat bread samples during dough fermentation, baking and storage. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 7, 323–328 (2017).

Saghafi, Z. et al. Influence of time and temperature on stability of added vitamin D 3 during cooking procedure of fortified vegetable oils. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 5, 43–48 (2018).

Acknowledgements

Data collection was funded by the following Grants: FIS PI17/1709, PI20/144 (State Secretary of R+D and FEDER/FSE), and the CIBERESP, Instituto de Salud Carlos III. Madrid, Spain.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.G.-C. developed the study concept. P.G.-C. and M.R.-A. participated in the generation of the study design. M.R.-A. and P.G.-C. conducted data analyses. M.R.-A. and P.G.-C. prepared the first manuscript draft, and J.R.B., R.O., F.R.-A., C.D.-V and M.G. provided critical revisions. P.G.-C., J.R.B., and F.R.-A. obtained funding. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Ayala, M., Banegas, J.R., Ortolá, R. et al. Cooking methods are associated with inflammatory factors, renal function, and other hormones and nutritional biomarkers in older adults. Sci Rep 12, 16483 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19716-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-19716-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.