Abstract

Aging, change in property depending on the elapsed time from preparation, is known to affect the rheological behavior of various materials. Therefore, whether magma ages must be examined to characterize potentially widespread volcanic phenomena related to the transition from rest to flow. To achieve this, we performed rheological measurements and microstructural analyses on basaltic andesite lava from the 1986 Izu-Oshima eruption. The rheology shows an initial overshoot of shear stress during start-up flow that correlates with the duration and the shear rate of a pre-rest time. This indicates that the yield stress of magma and lava increases with aging. The microstructure shows that original aggregates of crystals, which may grow during crystallization, coalesce during the pre-rest period to form clusters without changing the crystal volume fraction. We conclude that the clusters are broken by shear in the start-up flow, which induces the stress overshoot. Thus, aging in magma rheology will impact the understanding of dynamic flow.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Magma rheology is a key to understand widespread volcanic phenomena related to the flow of magma and lava; therefore, there have been many studies on it, as reviewed by1,2. The rheological behavior of magma is controlled not only by temperature, pressure, and chemical composition, but also by the presence of crystals and bubbles3,4,5,6,7. The effect of crystals is especially influential, and the volume of crystals increases with cooling and/or degassing8,9.

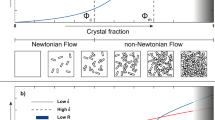

The crystal volume fraction is a critical parameter to describe the rheology of magma composed of crystals and melt. At low crystal volume fraction, magma behaves as a Newtonian fluid, whereas with an increase in the crystal volume fraction, the rheology of magma becomes complicated and non-Newtonian5,10,11. To date, major non-Newtonian behaviors have been examined at the steady state to extract one-to-one relationships, such as viscosity vs. crystal volume fraction12 and yield stress vs. crystal volume fraction13, because relational equations are required for simulations of magma and lava flow4,14. Equations to predict the effect of crystal shape on rheology are also proposed and widely applied1,15,16.

In contradiction to the formulated characteristics at the steady state, non-Newtonian rheology at non-steady state such as the start-up of flow is more complex. Previous studies have reported thixotropy11,17,18,19,20,21, which is the continuous decrease of viscosity with time when flow is applied to a sample that has been previously at rest and the subsequent recovery of viscosity in time when the flow is discontinued22,23. Although one explanation for the behavior is temporal alignment change of plagioclase crystals with shear20,24,25, the relationship between the rheology and the microstructure is less well understood.

As time-dependence, aging, or change in property depending on the elapsed time since a sample was prepared, has been under intense study in the fields of nonlinear physics and soft matter, because it has strong effects on rheology26,27,28,29. Many soft solids, such as polydomain defect textures in ordered mesophases of copolymers or surfactants may show rheological aging through coarsening dynamics, or through glassy rearrangement of domains, or both26. In the same manner, melt-crystal textures of magma can vary with time, generating transition from rest to flow and the associated rheological evolution such as changes in thixotropy. However, there is no study that has examined the appearance of aging in magma until now.

We performed experiments to shed some light on aging in magma rheology using lava samples from the 1986 Izu-Oshima eruption. We report rheological changes as functions of time and shear rate of pre-rest, during which the sample rests before the measurement. The results are combined with the microstructures of quenched samples under different conditions for pre-rest to discuss the relationship between the rheology and the microstructure in terms of aging. Finally, we discuss how the aging in magma rheology may practically affect the dynamic flow at a volcano.

Materials and methods

Sample preparation

The starting material for this study was a rock sample from lava produced by the 1986 eruption at Izu-Oshima, an isolated volcanic island, 110 km SSW of Tokyo, Japan. The eruptive sequence comprised three eruptions at summit crater A, fissures in the caldera floor (crater B), and fissures in the flank of the outer rim (crater C) in chronological order30. We used lava from fissure crater B (LB) because the aphyric basaltic andesite fully melts in a relatively short period of time and has a sufficiently low viscosity that is measurable within the mechanical constraints of our experimental system. The chemical data shown in Table S1 of the Supplementary Material is consistent with those of the other LB samples collected within one year after the eruption31,32. The rock sample was crushed and sieved to a particle size less than 4 mm for the experiment.

Experimental apparatus

The experimental system used in this study is an improved version of that described by33. The furnace was changed to a high-temperature muffle furnace (MSFS-1218, Yamada Denki Co., Ltd.) that can increase the temperature up to 1400°C. The LB sample was placed in an alumina crucible with 17% porosity. Porous alumina was selected to prevent fracture during water-quenching and to maximize the quenching rate. A concentric cylindrical viscometer (HBDV-II+Pro, Brookfield Engineering Laboratories, Inc.) was connected to an alumina rod introduced into the LB sample from a hole on the top of the furnace to measure the torque. To calculate the shear stress and the shear rate, the equations described in33 were used with the sample height (15 mm), the radius of the rod (2.5 mm), and the radius of container (9.5 mm). Note that the reaction between the alumina parts and the LB sample is limited to the interface and does not affect either the overall microstructure of the sample or the calculation of shear rate. Further details about the calculations are described in Text S1 of the Supplementary Material.

Experimental protocol

Experiments were performed in an atmospheric environment at 1 atm with the following steps. (1) The furnace was heated to 1300°C and the temperature was maintained for 6 h to achieve complete melting of the starting material. (2) A rod was inserted into the sample 3 h after heating was started in (1) and weak shear at 1.13 s−1 was imposed for separating gas between fragments of the sample gravitationally and tracking the rheological change. (3) The temperature was lowered to the experimental temperature of 1180°C and shearing at the rate imposed in (2) was continued until the sample has the equilibrium crystal content at the PT conditions. The temporal variation in the shear stress during the process is indicated in Fig. S1 of the Supplementary Material. The temperature of 1180°C, which is between the solidus and the liquidus, was selected to observe the effect of microstructural changes in crystals on the rheology. It is 80°C higher than the eruption temperature of LB, 1100°C estimated by31. (4) Preshearing was applied at 4.50 s−1 for 2 min. The shear rate was higher than that of all tests to initialize and homogenize the sample. (5) Pre-rest was set for \(t_{pr}\) to relax the sample before measurement, and allow recovery of the microstructure, or aging if it shows. During the pre-rest, zero or weak shear (\(\dot{\gamma }_{pr} \le\) 0.45 s−1) was imposed to examine if aging occurs with shear. (6) A shear-rate controlled test (SRC) was performed at a shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\)) within the range of 0.68−2.48 s−1, which is equivalent to that of actual lava flows34,35. (7) Processes (4)–(6) were repeated with changing \(t_{pr}\), \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\), and \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) to examine the rheological variations in magma induced by aging. After the series of SRCs, the rod was gently pulled out from the sample, and the sample was immediately quenched in water for observation using scanning electron microscopy (SEM; JSM-IT500, JEOL) and for micro-computed tomography (micro-CT; SkyScan 1272, Bruker).

Results and discussion

Rheology

Effect of pre-rest time

Figure 1a presents the effect of the pre-rest time (\(t_{pr}\)) on the subsequent SRC test. The shear stress relaxes smoothly towards a constant value after the shortest \(t_{pr}\) of 10 min. For longer \(t_{pr}\), the stress increases toward a peak in the start-up flow and falls to be a constant through the overshoot. The stress overshoot becomes pronounced, or the peak stress increases with \(t_{pr}\). The rheological variation with \(t_{pr}\) is evidence that magma shows aging. On the other hand, the stress eventually matches after the long amount of time/strain (\(\sim\) 400 s in Fig. 1a), regardless of \(t_{pr}\). The agreement in the final stress indicates the one-to-one relation between the shear stress and the shear rate at steady state that has been reported in many other magmatic systems to date7,33. Therefore, magma of which steady state seems simple, can show complex rheology at non-steady state due to aging.

Effect of shear rate during pre-rest

The occurrence of aging with shear is examined by changing \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) at the pre-rest time of 60 min, which is adequate to observe the aging effect, as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Figure 1b indicates that the stress overshoot becomes more predominant with low \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) than that without shear, while the shear stress remains constant without the experience of the overshoot at the highest \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) of 0.45 s−1. This indicates that aging occurs at \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) below 0.45 s−1 in this case, although the threshold may vary depending on the shear rate of the SRC test, and the crystal variations and shapes. There may be competition between aging and shear-rejuvenation (viscosity decrease in time under shear28) during the pre-rest process as it in flows of soft matters28,29. Aging is promoted by weak shear, while rejuvenation wins at high shear rate and diminishes the stress overshoot. Therefore, \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) is also a key parameter to induce the aging effect as well as \(t_{pr}\).

(a) Results of SRC tests at \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) of 1.13 s−1 after various pre-rest times \(t_{pr}\), as shown in the legend. The sample was not sheared during the pre-rest times (\(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0 s−1). (b) Results of SRC tests at \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) of 1.13 s−1 after t\(_{pr}\) = 60 min at various \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\), as shown in the legend.

Effect of shear rate in SRC test

The effect of shear rate imposed in SRC test, \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\), on the stress overshoot was investigated at five different \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) with a same pre-rest condition (\(t_{pr}\) = 60 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0 s−1). Figure 2a shows the relative stress to the final stress, \(\sigma /\sigma _{fin}\) as a function of time. The overshoot appeared in all cases, but became more evident with an increase in \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\). The linear \(\sigma _{fin}\) vs. \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) in the inset denotes a similar tendency to the data of magma at the steady state1,7,33. Therefore, magma of which the steady-state characteristics are simple, has the potential to show much more complex rheology induced by aging in the non-steady state as in the case of this study. Further discussion on the steady state is described in Text S3 of the Supplementary Material. Figure 2b presents the relative stress vs. strain calculated from the time and shear rate. The relationships are similar, regardless of \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\), although the strain to reach the peak stress of the overshoot and the final stress increase with increasing shear rate.

Results of SRC tests at various shear rates after pre-rest with t\(_{pr}\) of 60 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) of 0 s−1. \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\) are indicated by the colors in the legend of (b). \(\sigma _{fin}\) is the average value of the last 10 s. (a) Normalized shear stress vs. time. The inset shows the relation between the final stress \(\sigma _{fin}\), and the shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }_{src}\), and the standard deviation of \(\sigma _{fin}\) is included in the circle. (b) Normalized shear stress vs. strain.

Microstructure

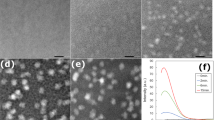

The experiments provided clear evidence of aging in the magma rheology as the stress overshoot in the start-up flow. The microstructural change related to the interaction between crystals during the pre-rest may cause the overshoot because whether it appears or not is dependent on the conditions, \(t_{pr}\) and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\). To investigate the relation between the rheological and microstructural variations induced by aging, imaging with SEM and micro-CT technology was applied. Here we show the results of two representative samples; one is an unaged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 10 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0 s−1, and the other is a shear-aged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 60 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0.02 s−1, which showed the most prominent overshoot (Fig. 1b). The conditions and methods for the microstructural observations are described in Text S2 of the Supplementary Material.

SEM observations

SEM observations revealed that both of the unaged and shear-aged samples contain Fe-Ti oxide and plagioclase in the melt (Fig. 3). The crystal volume fractions \(\phi\), estimated from 10 images using Fiji software36 are comparable; \(\phi\) of Fe-Ti oxide is 0.07 ± 0.010 in the unaged sample and 0.07 ± 0.012 in the shear-aged sample, and \(\phi\) of plagioclase is 0.09 ± 0.012 in the unaged sample and 0.09 ± 0.017 in the shear-aged sample. The crystal volume fraction does not change with aging; therefore, an increase in crystals is not the cause of the stress overshoot in the rheology. Compared with the critical crystal volume fraction \(\phi _c\), at which a crystal network first forms determined by13, the total crystal volume fractions of the two samples (ca. 0.16) are within the range of \(\phi _c\) for plagioclase, 0.08 \(< \phi _c<\) 0.20, and close to \(\phi _c\) for randomly-oriented cubes, 0.22. This is consistent with the results reported here, which show non-Newtonian rheology. With respect to the crystal alignments in Fig. 3, the crystals, Fe-Ti oxide in particular, do not exist alone but as aggregates, and the aggregates are larger and more noticeable in the shear-aged sample. Dense parts composed of the aggregated crystals are sparse in the shear-aged sample, where the estimated \(\phi\) has a larger error than that of the unaged sample. It can be interpreted that contact of the aggregates may proceed by slightt shear during pre-rest to form clusters, and the clusters are broken after the onset of the SRC test by shear that causes the stress overshoot. A similar process of shear-induced memory effect on reversible clusters composed of several unbreakable aggregates of primary particles has recently been proposed in the field of soft glass materials37.

Micro-CT imaging

To examine the 3D structure of the clusters grown by aging, analyses of micro-CT images were performed. Since the CT imaging cannot distinguish plagioclase from melt due to the subtle difference between the densities, here we focus on Fe-Ti oxide, of which 2D distribution strongly depended on aging (Fig. 3). In Fig. 4, large clusters of Fe-Ti oxide are present in all cross sections of the shear-aged sample, while small aggregates are more dispersed in the unaged sample. Image analyses were performed to obtain the quantitative characteristics of the clusters using Fiji software36 with MorpholibJ integrated library and plugin38. The detailed imaging conditions and the procedure for image processing are described in Text S2 of the Supplementary Material.

Table 1 shows the results of the image analyses. The number of objects detected is smaller while the volume is larger in the shear-aged sample than in the unaged sample. This indicates that pre-existent aggregates coalesce with time and become larger, thereby reducing their number during the pre-rest because the total volumes of Fe-Ti oxide in the two samples are equivalent. The results mean that aging affects not the volume of crystals but the crystal arrangement, which agrees well with the SEM observations. A reduction in sphericity would suggest that grown clusters have a greater variety of shape. Histograms of the original object volume and sphericity are shown in Fig. S2 of the Supplementary Material. With respect to the shape of equivalent ellipsoid, although the size increases with aging, the shape maintains a scaling relationship, which is evident in the normalized equivalent ellipsoid sizes. The aggregates are long in the shear-plane; therefore, it is easier for them to collide in the plane, so that residual shear-history before the pre-rest and weak shear during the pre-rest would promote the formation of clusters. On the other hand, the small aggregates dispersed in the unaged sample would be formed originally by the contact of crystals due to shear during crystallization and those may be scarcely broken by the shear imposed in this study. This could explain why the elevation of the major axis of the equivalent ellipsoids on the horizontal plane, or shear plane is close to zero. The effect of shear on crystal alignment has also been referred to in previous studies24,39.

Overall, this study concludes rheological changes are caused by forming crystal clusters by aging without changing characteristics of each crystal, so that this is different from the effects of crystal shape, size, and volume fraction1,12,13,15,16. We consider clustering is not caused by magnetic force between the oxides because the Curie temperature is much lower than our experimental temperature. Instead, shear-induced acceleration of synneusis, which is a hydrodynamic process that can drive the aggregation of preformed crystals40,41,42, is a possible mechanism of aging, although future works are required to explore the effect in detail.

Back-scattered electron images of cross-sectional surfaces of samples cut off at a height of 13 mm from the bottom. The dark gray and elongated rectangles are plagioclase, the white crystals are Fe-Ti oxide, and the background is melt/glass. The scale bars in the lower right corners are 200 μm. Each figure is a composite image in which 27 images are superimposed. (a) Unaged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 10 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0 s−1. (b) Shear-aged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 60 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0.02 s−1.

Micro-CT images of the same samples as those used for SEM observations. The white crystals are Fe-Ti oxide, the background is melt/glass and plagioclase. (a) Unaged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 10 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0 s−1. (b) Shear-aged sample with \(t_{pr}\) = 60 min and \(\dot{\gamma }_{pr}\) = 0.02 s−1. (a-1) and (b-1) are sagittal planes and (a-3) and (b-3) are coronal planes composed of 1531 images each. (a-2) and (b-2) are transverse planes.

Implication for magma flow inside volcanic conduit

This study shows that the peak stress of overshoot in the start-up flow increases if the magma has sufficient time at rest, and low shear rates promote the process. The temporal variation in magma rheology caused by aging would affect the dynamics of magma and lava associated with an eruption. An example is the formation of a high-viscosity plug in a shallow conduit, which would significantly affect the dynamics of Strombolian eruptions43,44,45. Aging would prompt plug formation as follows; (1) magma stops its ascent after degassing. (2) At the shallow conduit depth, the arrangement of crystals changes with time and form clusters by aging, which leads to yield stress. (3) Due to the yield stress, the stagnant magma separates from the main convection flow in the conduit. (4) Cooling and crystallization are facilitated in the stagnant magma. The process becomes dominant in the presence of Fe-Ti oxide since the liquidus increases under the oxidized state46. As a result, a high-viscosity plug is formed, increasing the explosivity of eruption. In this way, aging would play an important role during the initial stage of the plug formation. Although Fe-oxides, of which clusters were formed in our shear-aged sample, are less likely to observe at natural systems, this scenario is possible at shallow parts of volcanic conduit because there would be an oxidized state with oxidized recycled materials46,47 and magnetite nanolite48. Since magnetite nanolites could drastically increase the viscosity49, it makes a plug more viscous, and the structure becomes even stronger by aging, causing more explosive eruptions. We expect aging in other crystals, too. Especially, since clusters of plagioclase have been observed in natural products42 and experimental samples25, aging may affect the formation. That would be a next key question to address in future work.

Conclusions

Rheological measurements and microstructural observations were performed on aphyric basaltic andesite lava produced by the 1986 Izu-Oshima eruption. The rheological measurements indicated the overshoot of shear stress in the start-up flow by aging with sufficient pre-rest time, which became predominant in the case of imposing weak shear during the pre-rest. The microstructural observations revealed that original aggregates of crystals, which grew during crystallization, coalesce during the pre-rest to form clusters, and the clusters are broken by shear in the start-up flow, which induces the stress overshoot. The temporal variation in magma rheology caused by aging would prompt the formation of high-viscosity plug of magma flow inside a volcanic conduit and would control the onset/stop of magma and lava flows.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author, AK on reasonable request.

References

Mader, H. M., Llewellin, E. W. & Mueller, S. P. The rheology of two-phase magmas: A review and analysis. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 257, 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2013.02.014 (2013).

Kolzenburg, S., Chevrel, M. & Dingwell, D. Magma/suspension rheology. In Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry, 1st ed (eds Neuville, D. et al.) 639–720 (Mineralogical Society of America, 2022). Chap. 14. https://doi.org/10.2138/rmg.2020.86.X.

Manga, M., Castro, J. & Cashman, K. V. Rheology of bubble-bearing magmas. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 87, 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-0273(98)00091-2 (1998).

Caricchi, L. et al. Non-Newtonian rheology of crystal-bearing magmas and implications for magma ascent dynamics. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 264(3–4), 402–419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2007.09.032 (2007).

Moitra, P. & Gonnermann, H. Effects of crystal shape- and size-modality on magma rheology. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005554 (2015).

Namiki, A. & Tanaka, Y. Oscillatory rheology measurements of particle- and bubble-bearing fluids: Solid-like behavior of a crystal-rich basaltic magma. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44(17), 8804–8813. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GL074845 (2017).

Vona, A. et al. The complex rheology of megacryst-rich magmas: The case of the mugearitic “cicirara” lavas of Mt. Etna volcano. Chem. Geol. 458, 48–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2017.03.029 (2017).

Lindoo, A., Larsen, J. F., Cashman, K. V. & Oppenheimer, J. Crystal controls on permeability development and degassing in basaltic andesite magma. Geology 45(9), 831–834. https://doi.org/10.1130/G39157.1 (2017).

Di Fiore, F., Vona, A., Kolzenburg, S., Mollo, S. & Romano, C. An extended rheological map of Pāhoehoe-‘A’ā transition. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 126(7), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021JB022035 (2021).

Pistone, M., Caricchi, L., Ulmer, P., Reusser, E. & Ardia, P. Rheology of volatile-bearing crystal mushes: Mobilization vs. viscous death. Chem. Geol. 345, 16–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemgeo.2013.02.007 (2013).

Liu, Z., Zhang, L., Malfliet, A., Blanpain, B. & Guo, M. Non-Newtonian behavior of solid-bearing silicate melts: An experimental study. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids 493(March), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnoncrysol.2018.04.042 (2018).

Costa, A., Caricchi, L. & Bagdassarov, N. A model for the rheology of particle-bearing suspensions and partially molten rocks. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10(3), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GC002138 (2009).

Saar, M. O., Manga, M., Cashman, K. V. & Fremouw, S. Numerical models of the onset of yield strength in crystal-melt suspensions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 187(3–4), 367–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00289-8 (2001).

Hérault, A., Bilotta, G., Vicari, A., Rustico, E. & del Negro, C. Numerical simulation of lava flow using a GPU SPH model. Ann. Geophys. 54(5), 600–620. https://doi.org/10.4401/ag-5343 (2011).

Mueller, S. P., Llewellin, E. W. & Mader, H. M. The rheology of suspensions of solid particles. Proc. R. Soc. 466, 1201–1228. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.2009.0445 (2014).

Klein, J., Mueller, S. P. & Castro, J. M. The Influence of crystal size distributions on the rheology of magmas: New insights from analog experiments. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 18(11), 4055–4073. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017GC007114 (2017).

Ryerson, F. J., Weed, H. C. & Piwinskii, A. J. Rheology of subliquidus magmas. 1. Picritic compositions. J. Geophys. Res. 93(B4), 3421–3436. https://doi.org/10.1029/JB093iB04p03421 (1988).

Pinkerton, H. & Norton, G. Rheological properties of basaltic lavas at sub-liquidus temperatures: Laboratory and field measurements on lavas from Mount Etna. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 68(4), 307–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/0377-0273(95)00018-7 (1995).

Sato, H. Viscosity measurement of subliquidus magmas: 1707 basalt of Fuji volcano. J. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 100(4), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.2465/jmps.100.133 (2005).

Ishibashi, H. & Sato, H. Viscosity measurements of subliquidus magmas: Alkali olivine basalt from the Higashi-Matsuura district, Southwest Japan. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 160(3–4), 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2006.10.001 (2007).

Ishibashi, H. Non-Newtonian behavior of plagioclase-bearing basaltic magma: Subliquidus viscosity measurement of the 1707 basalt of Fuji volcano, Japan. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 181(1–2), 78–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvolgeores.2009.01.004 (2009).

Barnes, H. A. Thixotropy—a review. J. Non-Newtonian Fluid Mech. 70, 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-2494.1987.tb00472.x (1997).

Mewis, J. & Wagner, N. J. Thixotropy. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 147–148(C), 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cis.2008.09.005 (2009).

Vona, A., Romano, C., Dingwell, D. B. & Giordano, D. The rheology of crystal-bearing basaltic magmas from Stromboli and Etna. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75(11), 3214–3236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gca.2011.03.031 (2011).

Chevrel, M. et al. Viscosity measurements of crystallizing andesite from Tungura-hua volcano (Ecuador). Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 16(1), 870–889. https://doi.org/10.1002/2014GC005684.Key (2015).

Fielding, S. M., Sollich, P. & Cates, M. E. Aging and rheology in soft materials. J. Rheol. 44(2), 323–369. https://doi.org/10.1122/1.551088 (2000).

Cloitre, M., Borrega, R. & Leibler, L. Rheological aging and rejuvenation in microgel pastes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85(22), 4819–4822. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.85.4819 (2000).

Moller, P. C. F., Mewis, J. & Bonn, D. Yield stress and thixotropy: On the difficulty of measuring yield stresses in practice. Soft Matter 2(4), 274–283. https://doi.org/10.1039/b517840a (2006).

Kurokawa, A., Vidal, V., Kurita, K., Divoux, T. & Manneville, S. Avalanche-like fluidization of a non-Brownian particle gel. Soft Matter 11(46), 9026–9037. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5sm01259g (2015).

Endo, K. et al. Tephrochronological study on the 1986–1987 eruptions of Izu-Oshima volcano, Japan. Bull. Volcanol. Soc. Jpn. 33(2), 32–51 (1988).

Fujii, T. et al. Petrology of the lavas and ejecta of the November, 1986 eruption of Izu-Oshima volcano. Bull. Volcanol. Soc. Jpn. 33, 234–254 (1988) (in Japanese with English abstract).

Aramaki, S. & Fujii, T. Petrological and geological model of the 1986–1987 eruption of Izu-Oshima volcano. Bull. Volcanol. Soc. Jpn. 33, 297–306 (1988) (in Japanese with English abstract).

Kurokawa, A. K., Miwa, T. & Ishibashi, H. A simple procedure for measuring magma rheology. J. Disaster Res. 14(4), 616–622. https://doi.org/10.20965/jdr.2019.p0616 (2019).

Piombo, A. & Dragoni, M. Evaluation of flow rate for a one-dimensional lava flow with power-law rheology. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36(22), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009GL041024 (2009).

Kolzenburg, S., Giordano, D., Hess, K. U. & Dingwell, D. B. Shear rate-dependent disequilibrium rheology and dynamics of basalt solidification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45(13), 6466–6475. https://doi.org/10.1029/2018GL077799 (2018).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.2019 (2012).

Sudreau, I., Manneville, S., Servel, M. & Divoux, T. Shear-induced memory effects in boehmite gels. J. Rheol. 66, 91. https://doi.org/10.1122/8.0000282 (2022).

Legland, D., Arganda-Carreras, I. & Andrey, P. MorphoLibJ: Integrated library and plugins for mathematical morphology with ImageJ. Bioinformatics 32(22), 3532–3534. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btw413 (2016).

Bergantz, G. W., Schleicher, J. M. & Burgisser, A. On the kinematics and dynamics of crystal-rich systems. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 122(8), 6131–6159. https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JB014218 (2017).

Vogt, J. H. L. The physical chemistry of the crystallization and magmatic differentiation of igneous rocks. J. Geol. 29, 318–350 (1964).

Vance, J. A. On synneusis. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 24(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00398750 (1969).

Wieser, P. E. et al. To sink, swim, twin, or nucleate: A critical appraisal of crystal aggregation processes. Geology 47(10), 948–952. https://doi.org/10.1130/G46660.1 (2019).

Del Bello, E. et al. Viscous plugging can enhance and modulate explosivity of strombolian eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 423, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2015.04.034 (2015).

Suckale, J., Keller, T., Cashman, K. V. & Persson, P. O. Flow-to-fracture transition in a volcanic mush plug may govern normal eruptions at Stromboli. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43(23), 12071–12081. https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL071501 (2016).

Oppenheimer, J. et al. Analogue experiments on the rise of large bubbles through a solids-rich suspension: A weak plug model for Strombolian eruptions. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 531, 115931 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2019.115931 (2020).

D’Oriano, C., Bertagnini, A., Cioni, R. & Pompilio, M. Identifying recycled ash in basaltic eruptions. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05851 (2014).

Deardorff, N. & Cashman, K. Rapid crystallization during recycling of basaltic andesite tephra: Timescales determined by reheating experiments. Sci. Rep. 7(April), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep46364 (2017).

Mujin, M., Nakamura, M. & Matsumoto, M. In-situ FE-SEM observation of the growth behaviors of Fe particles at magmatic temperatures. J. Cryst. Growth 560–561, 126043 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrysgro.2021.126043 (2021).

Di Genova, D. et al. In situ observation of nanolite growth in volcanic melt: A driving force for explosive eruptions. Science Advances 6(39), eabb0413. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abb0413 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank Stephan Kolzenburg and an anonymous reviewer for their constructive comments and suggestions that helped to improve the manuscript. Masashi Nagai helped to prepare the experimental materials and perform SEM-EDS analyses. XRF analysis was conducted by Atsushi Yasuda and Natsumi Hokanishi at the Earthquake Research Institute. Micro-CT imaging was performed by Takehiro Yamada at Saitama Industrial Technology Center. Masatoshi Ohashi gave effective advice on image processing. We are grateful for their help. This work was supported by the MEXT “Integrated Program for Next Generation Volcano Research and Human Resource Development” and JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP17K14383.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K. performed experiments and analyses, and wrote the manuscript. T.M. and H.I reviewed the manuscript, and contributed to the discussion and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kurokawa, A.K., Miwa, T. & Ishibashi, H. Aging in magma rheology. Sci Rep 12, 10015 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14327-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-14327-2

This article is cited by

-

Vulcanian eruption processes inferred from volcanic glow analysis at Sakurajima volcano, Japan

Bulletin of Volcanology (2023)

-

A chemical threshold controls nanocrystallization and degassing behaviour in basalt magmas

Communications Earth & Environment (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.