Abstract

The development of mid-infrared (mid-IR) tunable lasers has been driving various laser spectroscopic technologies. Herein, we report wavelength-scanning cavity ring-down spectroscopy (WS-CRDS) in the mid-IR region using an electronically tuned Cr:ZnSe (ET-Cr:ZnSe) laser, which could achieve a nanosecond pulse operation, with broad wavelength tuning of 2–3 µm. This allowed WS-CRDS-induced trace detection of the refrigerant, CH2F2. A CH2F2 detection limit of 0.66 ppm (3σ), and the detection of trace H2O in CH2F2 was realized using the broad wavelength-tuning range feature, demonstrating the effectiveness of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser in WS-CRDS. We believe that our method would accelerate the development of various trace-gas detection technologies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the popularization of air-conditioning systems, refrigerants have become indispensable. Currently, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) replacements1,2 and exhibit a low ozone depletion potential (ODP), are mainly used as refrigerants. However, HFCs are subjected to reduction and emission control regulations under the Montreal and Kyoto Protocol because of their flammability and high global warming potential (GWP)3,4. Their leakage monitoring, crucial for environmental conservation and climate research, necessitates the development of trace refrigerant detection technology.

Although cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS)5,6, photoacoustic spectroscopy7, and tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy with multipass gas cells8 are employed for high-sensitive detection of various trace volatile organic compounds (VOCs), their implementation in trace HFC detection has not yet been demonstrated. Among these methods, CRDS is a widely used optical sensing technique for ultrahigh-sensitivity measurements, wherein the effective optical path length can be significantly increased using a highly reflective cavity. To detect trace HFCs using CRDS, a laser that can tune the wavelength to the mid-infrared (IR) absorption peak of HFCs is required. Some HFCs exhibit strong absorptions in the mid-IR region (wavelength > 3 µm)9,10,11. Recently, strong absorptions at 2.1–2.5 µm have been noticed for difluoromethane (CH2F2), 2,3,3,3-tetrafluoroprop-1-ene (CH2=CFCH3), and (E)-1,3,3,3-tetrafluoroprop-1-ene (CHF=CHCF3)12. CH2=CFCH3 and CHF=CHCF3 are hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs) that are new candidates for refrigerants. Compared to low-molecular-weight gases (e.g., CH4, C2H4, and CO2), HFCs exhibit broad absorption spectra under ordinary temperature and pressure. In CRDS, distributed feedback lasers operate at a single frequency, and quantum cascade lasers are used for detecting low-molecular-weight gases13,14. However, the wavelength tuning ranges (e. g., 1–5 nm) of these lasers are narrower than the absorption spectral width of the HFCs; thus, the entire absorption spectrum of HFCs, spanning several 10-nm spectral regions, cannot be measured and the identification of the impurities based on the absorption spectral shape becomes difficult. For trace HFC detection using CRDS, a laser with a broad wavelength tuning range that includes the entire absorption spectral region is effective. However, increasing the CRD mirror reflectance to obtain a high sensitivity drastically reduces the CRDS signal intensity. Therefore, high-intensity and broadly tunable mid-IR lasers are required for trace HFC.

Cr2+-doped chalcogenides (e.g., Cr:ZnSe, Cr:ZnS, and Cr:CdSe), enabling direct access to the spectral range of 2–3 μm because of their broad fluorescence region and large stimulated-emission cross sections, have been used as the laser media in mid-IR tunable lasers15,16. These media prompted the development of high-power tunable lasers and ultrashort pulse lasers in the mid-IR region, without using nonlinear frequency conversion techniques17,18,19. Among these lasers, the 2–3 µm tunable nanosecond pulsed lasers are highly adaptable for the trace detection of CH2F2 using CRDS. Furthermore, because the output power per unit wavelength is higher than that of the supercontinuum laser, CRDS with a high signal-to-noise ratio can be realized. An electronically-tuned Cr:ZnSe (ET-Cr:ZnSe) laser equipped with an acousto-optic tunable filter (AOTF) as a wavelength tuning element reportedly produced a tuning in the range 2.17–2.71 µm and pulse energy of 7.9 mJ at 2.41 µm, which demonstrates a rapid wavelength tuning using a computer program20. Using Cr:CdSe, a grating-tuned laser with a broad tuning range of 2.25–3.08 μm and output energy of 4 mJ at 2.64 μm has been demonstrated21. However, these lasers are unsuitable for CRDS because the relaxation oscillations modulate the temporal profiles of the nanosecond pulses into multipeak pulses. Mirov et al.22 reported a broadly tunable Cr:ZnS laser using a Q-switched Er:YAG laser with a 50 ns pulse width, showing an output energy of 7 mJ at 2.25 μm and a tuning range of 1.95–2.65 μm via grating rotation. Although it can be applied to CRDS, the grating tuning method is inferior in wavelength controllability to the electronic tuning method in terms of wavelength-tuning speed, wavelength reproducibility, and random-wavelength switching. Both optimal temporal profile and high wavelength controllability are required for wavelength-scanning CRDS (WS-CRDS) in the 2–3 µm region.

Herein, we report trace CH2F2 detection using CRDS with an ET-Cr:ZnSe laser, which was improved to perform single-peak nanosecond pulse operation. We also demonstrate the detection of CH2F2 and H2O via the rapid wavelength scanning of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser. Thus, the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser is an effective light source for WS-CRDS in the mid-IR region.

Results and discussion

WS-CRDS system using ET-Cr:ZnSe laser

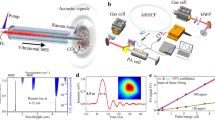

A schematic of the WS-CRDS setup for CH2F2 detection, composed of an ET-Cr:ZnSe laser, a ring-down cavity (RDC), a mid-IR detector (PVI-4TE-4, VIGO system), and a gas supply system, is shown in Fig. 1. We used a 15 mm-long antireflection-coated (for 1.5–2.7 µm) polycrystalline Cr:ZnSe (IPG Photonics, Inc.) as the laser medium with a Cr2+ doping concentration of 9.0 × 1018 cm−3. A Z-fold laser cavity configuration was developed using Cr:ZnSe, two folding mirrors (Concave radius = 500 mm), a total reflector, an output coupler, and an AOTF (Gooch & Housego). The output coupler and total reflector were flat, showing 70 and 99.5% reflections, respectively, for 2.1–3.5 μm. The folding mirrors were high-reflection-coated for 2.1–3.5 μm. We used a laser-diode-pumped 2 µm Q-switched Tm:YAG laser with a 10 Hz repetition rate as the pump source23, exhibiting maximum pulse energy of 1.8 mJ with a 53 ns pulse duration. To tune the wavelength, the AOTF was placed inside the cavity and connected to a radiofrequency (RF) driver whose power could be adjusted using a scanning computer program. This AOTF-based electronic tuning method promises high-speed continuous- or random-access tuning over a broad mid-IR region20. The laser output was passed through a lens pair and input to a ring-down cavity (RDC) consisting of two highly reflective mirrors placed 50 cm apart, each with a concave radius of 1000 m and a specified reflection of > 99.99% at 2.64 µm (LohnStar Optics, Inc.). The output beam from the RDC was focused on the mid-IR detector. The inlet and outlet of the RDC were connected to the gas supply and scroll pumps, respectively. Among the HFCs, we selected CH2F2 as the sample gas because it is mainly used in air-conditioning systems. CH2F2 exhibits a zero ODP and a GWP of 677, which is approximately 1/3rd of the GWP of CFCs and HCFCs24. The gas supply system was composed of a mass flow controller and reference gases (N2 and CH2F2). The CH2F2 concentrations were adjusted by controlling the flow rate of each reference gas. The ring-down signals were acquired on a computer using LabVIEW. All the experiments were performed at atmospheric pressure.

Output performances of ET-Cr:ZnSe laesr

Figure 2 shows the output performance of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser. The wavelength-tuning range and the filter tuning curve of ET-Cr:ZnSe laser are shown in Fig. 2a. We measured the wavelength and output energy by changing the RF signals fed into the AOTF. The wavelength was measured using a wavemeter (IR-III WS6-200, HighFinesse). The wavelength tuning range of 2.21–2.77 μm was achieved by changing the RF signals between 35.2 and 44.8 MHz. The maximum output energy of 0.3 mJ was obtained at 2.41 µm under a 1.8-mJ pumping. The decline of the output energy at approximately 2.6 µm is caused by water vapor absorption in the atmosphere. Figure 2b shows the output optical spectra of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser. For the RF signals of 37.5, 39.2, 41.0, 42.9, and 45.0 MHz, the spectral peaks at 2631.3, 2523.9, 2419.1, 2324.3, and 2218.5 nm were measured, respectively, using a spectrometer (ASP-IR-3.5, AVESTA Ltd.), and the spectral width at each wavelength was 1–1.5 cm−1. The temporal and spatial profiles at 2.4 µm are shown in Fig. 2c. The ET-Cr:ZnSe laser drove 14 ns pulses at 2.4 µm under 53 ns pumping pulses, and the spatial beam profile in the TEM00 mode was observed. In the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser reported in20, the relaxation oscillations modulate the temporal profiles of the nanosecond pulses into multipeak pulses due to the long pump duration (\({\tau }_{p}\)= 300 ns). However, in this study, the short pump duration (\({\tau }_{p}\)= 53 ns) suppresses the relaxation oscillations and provides single peak pulses. Figure 2d shows the pulse duration as a function of wavelength. Pulse durations of 14–20 ns were observed in 2250–2650 nm, whereas those longer than 20 ns were observed in the outer regions of 2250 and 2650 nm owing to the small stimulate-emission cross-sections of Cr:ZnSe.

WS-CRDS CH2F2 detection

The absorption spectrum of the CH2F2 (1000 ppm) reference gas is shown in Fig. 3. A Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer equipped with a multipass gas cell (optical pass length = 12 m) was used to measure the absorption spectrum. The absorption peaks of CH2F2 appear at approximately 2220 and 2422 nm. The absorption spectra observed in the 2600–2800 nm region originated from the H2O impurity. The absorption peak at 2422 nm is around the gain center of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser. The CRDS-based detection of CH2F2 was performed at 2422 nm to obtain high sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratios.

The ring-down times (RDTs) at which CH2F2 and N2 (99.999%) were introduced into the RDC are shown in Fig. 4a. An RDT of 16.6 µs was measured when the RDC was purged with N2. As the CH2F2 concentration inside the RDC increased from 6 to 47 ppm, the RDTs decreased from 14.4 to 8.3 µs. From the experimentally obtained RDT, the effective reflectivity and optical length of the RDC were estimated to be R = 99.99% and leff = 5 km, respectively. This reflectivity is reasonable compared to the specifications provided by the vendor, according to the relationship \(\tau =l/c(1-R)\), where l is the RDC length. Figure 4b shows a histogram of the RDTs in the N2-purged RDC at 2422 nm. The average and standard deviation (\(\sigma (\tau )\)) of the RDT were 16.6 µs and 65 ns, respectively. The noise-equivalent absorption sensitivity (NEAS)25 of the CH2F2 detection was calculated as \(\mathrm{NEAS}= \sigma (\tau )/c\cdot {\tau }^{-2}\cdot {{f}_{a}}^{-1/2}\), where \(\sigma (\tau )\) is the standard deviation of the RDT (\(\tau\)) in the N2-purged RDC, \(c\) is the speed of light, and \({f}_{a}\) is the RDT acquisition rate; \(\sigma (\tau )/\tau\) = 0.39% was obtained from the histogram, indicating NEAS ≈ 2.5 × 10–9 cm-1 Hz-1/2 (\({f}_{a}=10 \,\mathrm{Hz}\)). Figure 4c shows a linear regression plot of the CH2F2 concentration and the absorption coefficient. The CH2F2 concentrations were adjusted in the range of 0.5–47 ppm by changing the mixing ratio of the CH2F2 (100 ppm) and N2 (99.999%) reference gases using a gas dilution system. A linear fit to the experimental data yielded an R2 value of 0.9849, indicating an excellent linear response of the sensor. We estimated the detection limit within three standard deviations (3σ)26. The 3σ value of ~ 0.2 µs, obtained from the histogram, corresponded to a concentration of 0.66 ppm when compared with the linear-fitting line shown in Fig. 4c. Figure 4d shows the results of the continuous measurement of CH2F2 absorption when its concentration was changed gradually. The total flow rate of CH2F2 (100 ppm) and N2 (99.999%), provided by the gas supply system, was kept constant at 1 L/min, and the mixing ratio of CH2F2 and N2 was gradually changed from 0.15 L/min:0.85 L/min to 0.6 L/min:0.4 L/min. We succeeded in monitoring the continuous changes in the CH2F2 concentration in the RDC, implying that it is possible to monitor the CH2F2 leakage constantly for a ppm-level concentration.

CH2F2 detection using CRDS with the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser. (a) RDTs under changing CH2F2 concentrations. Each RDT was obtained by averaging 32 ring-down events. (b) Histogram of the RDTs in the N2-purged RDC. In total, 7300 ring-down events were used. (c) Linear regression plot between the CH2F2 concentration and the absorption coefficient. Each RDT was obtained by averaging 32 ring-down events. (d) Continuous measurement results with cascading CH2F2 concentration changes.

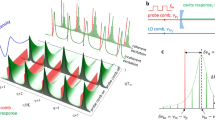

The CRD absorption spectrum of CH2F2 (Fig. 5a) was obtained by measuring the RDTs while scanning the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser wavelength in 2360–2480 nm, which was realized by sweeping the RF signals (39.62–41.76 MHz) fed into the AOTF. The scanning speed for each wavelength was 0.2 s. The absorption spectra of the reference gas CH2F2 (100 ppm) in the 2360–2480 nm region and those of CH2F2 (1000 ppm) and pure H2O are shown in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. The pure H2O absorption spectra (red curve) were obtained from the high-resolution transmission molecular absorption (HITRAN) database. Compared to the absorption spectrum in Fig. 5b, the CRD absorption spectrum in Fig. 5a shows several absorption peaks other than those of CH2F2. These absorption peaks are in excellent agreement with the H2O absorption peaks shown in Fig. 5b. This result indicates that the high sensitivity and broad-wavelength scanning features of the CRDS allowed the detection of trace H2O included as an impurity in the CH2F2 reference gas. In the future, our WS-CRDS is also expected to detect HFOs (CH2=CFCH3 and CHF=CHCF3) that show absorption in the same wavelength region12.

Conclusions

We demonstrated trace CH2F2 detection using WS-CRDS in a broad mid-IR region. WS-CRDS was performed using an ET-Cr:ZnSe laser with high wavelength controllability and single-peak nanosecond pulse operation, developed in this study. A CH2F2 detection limit of 0.66 ppm was realized along with real-time monitoring of the changes in CH2F2 concentration, thereby establishing the suitability of the proposed WS-CRDS method for leakage monitoring of CH2F2. Furthermore, the broad wavelength-tuning range of the ET-Cr:ZnSe laser allowed the detection of multiple and high-molecular-weight components that exhibit broad mid-IR absorption spectra. In the analysis of human respiration and gas released from plants, high-molecular-weight VOCs (ppb level) are often measured. Therefore, by improving the detection sensitivity, the WE-CRDS is also expected to be applied for their analysis.

Methods

Cr:ZnSe

A polycrystalline Cr:ZnSe (IPG Photonics, Inc.) was used as the laser medium. The concentration of Cr2+ was approximately 9.0 × 1018 cm−3, which was doped using the diffusion doping method27,28. The Cr:ZnSe was directly mounted on a copper stage without forced cooling.

Electronic wavelength tuning via AOTF

Electronic wavelength tuning was realized using the AOTF, which consisted of TeO2 and a transducer, inside the laser cavity29,30. TeO2 was anti-reflection-coated for 2.0–2.7 μm. An RF signal was fed to TeO2 through the transducer, causing an acoustic wave to propagate in the TeO2, and the selected wavelength was diffracted by the acousto-optic effect. A diffraction efficiency > 90% was achieved for 2.0–2.7 μm. Here, the Cr:ZnSe laser cavity was placed along the axis of the diffracted beam. Therefore, by varying the RF signal fed to the AOTF, the lasing wavelength can be changed automatically. In our laser system, the RF was varied from 35 to 46 MHz and the RF power was set to 5 W.

Data availability

The data associated with this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Velders, G. J. M., Fahey, D. W., Daniel, J. S., McFarland, M. & Andersen, S. O. The large contribution of projected HFC emissions to future climate forcing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 10949–10954. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0902817106 (2009).

Stanley, K. M. et al. Increase in global emissions of HFC-23 despite near-total expected reductions. Nat. Commun. 11, 397. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13899-4 (2020).

UNEP Ozone Secretariat. The Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. http://ozone.unep.org/en/treatiesand-decisions/montreal-protocol-substances-deplete-ozone-layer, (2008).

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Kyoto Protocol. http://unfccc.int/kyoto_protocol/items/2830.php, (2014).

De, A., Banik, G. D., Maity, A., Pal, M. & Pradhan, M. Continuous wave external-cavity quantum cascade laser-based high-resolution cavity ring-down spectrometer for ultrasensitive trace gas detection. Opt. Lett. 41, 1949–1952. https://doi.org/10.1364/OL.41.001949 (2016).

Maity, A., Pal, M., Banik, G. D., Maithani, S. & Pradhan, M. Cavity ring-down spectroscopy using an EC-QCL operating at 7.5 μm for direct monitoring of methane isotopes in air. Laser Phys. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1612-202X/aa8584 (2017).

Yin, X. et al. ppb-level SO2 photoacoustic sensors with a suppressed absorption-desorption effect by using a 7.41 μm external-cavity quantum cascade laser. ACS Sens. 5, 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.9b02448 (2020).

Ma, G. M. et al. Tracing acetylene dissolved in transformer oil by tunable diode laser absorption spectrum. Sci. Rep. 7, 14961. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-13823-0 (2017).

Wong, A. et al. High resolution far infrared spectroscopy of HFC-134a using a collisional cooling cell adapted to a synchrotron source. Chem. Phys. Lett. 634, 225–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cplett.2015.06.019 (2015).

Smith, K. M., Duxbury, G., Newnham, D. A. & Ballard, J. High-resolution mid-IR molecular absorption spectroscopy of collisionally cooled hydroÑuorocarbon vapours. J. Chem. Soc. 93, 2735 (1997).

Stoppa, P. et al. FTIR spectra of CH2F2 in the 1000–1300 cm−1 region: Rovibrational analysis and modeling of the Coriolis and anharmonic resonances in the ν3, ν5, ν7, ν9 and 2ν4 polyad. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 175, 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2016.01.035 (2016).

Minamida, T., Haikawa, T., Sato, K., Wada, S. & Yumoto, M. "GAS DETECTION DEVICE AND GAS LEAKAGE DETECTION SYSTEM," JP Patent Application (2020)-180465.

Wahl, E. H. et al. Ultra-sensitive ethylene post-harvest monitor based on cavity ring-down spectroscopy. Opt. Express 14, 1673–1684. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.14.001673 (2006).

Sonnenschein, V. et al. A cavity ring-down spectrometer for study of biomedical radiocarbon-labeled samples. J. Appl. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5041015 (2018).

Carrig, T. J. Transition-metal-doped chalcogenide lasers. J. Electron. Mater. 31, 759–769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11664-002-0233-1 (2002).

Mirov, S. B. et al. Progress in mid-IR lasers based on Cr and Fe-doped II–VI chalcogenides. IEEE J. Select. Topics Quantum Electron. 21, 292–310. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2014.2346512 (2015).

Yumoto, M., Saito, N. & Wada, S. 50 mJ/pulse, electronically tuned Cr:ZnSe master oscillator power amplifier. Opt. Express 25, 32948. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.25.032948 (2017).

Moskalev, I. et al. 140 W Cr:ZnSe laser system. Opt. Express 24, 21090–21104. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.021090 (2016).

Vasilyev, S. et al. Ultrafast middle-IR lasers and amplifiers based on polycrystalline Cr:ZnS and Cr:ZnSe. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 2636. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.7.002636 (2017).

Yumoto, M., Saito, N., Takagi, U. & Wada, S. Electronically tuned Cr:ZnSe laser pumped with Q-switched Tm:YAG laser. Opt. Express 23, 25009–25016. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.025009 (2015).

Yumoto, M. et al. High-energy, nanosecond pulsed Cr:CdSe laser with a 2.25–3.08 μm tuning range for laser biomaterial processing. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 5645–5653. https://doi.org/10.1364/BOE.9.005645 (2018).

Mirov, S. B. et al. Frontiers of mid-IR lasers based on transition metal doped chalcogenides. IEEE J. Select. Topics Quantum Electron. 24, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1109/JSTQE.2018.2808284 (2018).

Okabayashi, Y. et al. 2 µm Tm: YAG laser with pulse-on-demand operation. Proc. SPIE 11664, 1166407 (2021).

McLinden, M. O., Brown, J. S., Brignoli, R., Kazakov, A. F. & Domanski, P. A. Limited options for low-global-warming-potential refrigerants. Nat. Commun. 8, 14476. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms14476,Pubmed:28211518 (2017).

Long, D. A., Truong, G.-W., van Zee, R. D., Plusquellic, D. F. & Hodges, J. T. Frequency-agile, rapid scanning spectroscopy: Absorption sensitivity of 2×10-12 cm-1 Hz-1/2 with a tunable diode laser. Appl. Phys. B 114, 489–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-013-5548-5 (2014).

Shrivastava, A. & Gupta, V. B. Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of the analytical methods. Chron. Young Sci. 2, 21–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5186.79345 (2011).

Levchenko, V. I. et al. Preparation and properties of bulk ZnSe: Cr single crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 198–199(980–983), 980–983. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(98)01098-7 (1999).

Ndap, J.-O., Chattopadhyay, K., Adetunji, O. O., Zelmon, D. E. & Burger, A. Thermal diffusion of Cr2+ in bulk ZnSe. J. Cryst. Growth 240, 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-0248(02)00872-2 (2002).

Chang, I. C. Noncollinear acousto-optic filter with large angular aperture. Appl. Phys. Lett. 25, 370–372. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1655512 (1974).

Chang, I. C. Acousto-optic tunable filters. Opt. Eng. 20, 824–829. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.7972821 (1981).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Public/Private R&D Investment Strategic Expansion Program (PRISM). The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Y. Okabayashi and Dr. S. Imai at the mid-infrared laser source laboratory, RIKEN, and Mr. Y. Tomihari at OXIDE Corp. for providing the 2 µm Q-switched Tm:YAG laser.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. conceived and conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. Y.K. performed the experiments and analysed the data. S.W. supervised the project. All the authors contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yumoto, M., Kawata, Y. & Wada, S. Mid-infrared-scanning cavity ring-down CH2F2 detection using electronically tuned Cr:ZnSe laser. Sci Rep 12, 7879 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12019-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12019-5

This article is cited by

-

Mid-infrared supermirrors with finesse exceeding 400 000

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.