Abstract

Many lizard species use caudal autotomy, the ability to self-amputate a portion of the tail, as an effective but costly survival strategy. However, as a lizard grows, its increased size may reduce predation risk allowing for less costly strategies (e.g., biting and clawing) to be used as the primary defence. The King’s skink (Egernia kingii) is a large scincid up to approximately 244 mm snout to vent length (SVL) in size when adult. Adults rely less on caudal autotomy than do juveniles due to their size and strength increase during maturation. It has been hypothesised that lower behavioural reliance on autotomy in adults is reflected in loss or restriction of caudal vertebrae fracture planes through ossification as caudal intra-vertebral fracture planes in some species ossify during ontogenetic growth. To test this, we used micro-CT to image the tails of a growth series of seven individuals of E. kingii. We show that fracture planes are not lost or restricted ontogenetically within E. kingii, with adults retaining between 39–44 autotomisable vertebrae following 5–6 non-autotomisable vertebrae. Even though mature E. kingii rely less on caudal autotomy than do juveniles, this research shows that they retain the maximum ability to autotomise their tails, providing a last resort option to avoid threats. The potential costs associated with retaining caudal autotomy are most likely mitigated through neurological control of autotomy and E. kingii’s longevity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Autotomy, the self-induced loss of a body part, usually to avoid predation, is found across multiple taxa from invertebrates to vertebrates1,2. In lizards, the ability to shed a portion of their tail, providing a distraction to the predator and an opportunity for the lizard to escape, is one of the most familiar examples of autotomy3,4,5. Once autotomised, the tail regenerates over time, with the original bony vertebrae replaced by a rigid cartilaginous rod that lacks autotomy planes6,7. Although caudal autotomy is a very effective anti-predation strategy, how much of the tail is autotomised and the time and energy invested into regenerating the tail, can incur short- and long-term costs associated with locomotion, growth, reproduction and subsequent survival8,9,10,11,12. The fitness costs however, both short- and long-term, can potentially be mitigated in certain species depending on specific life-history characteristics and behavioural traits12.

Lizard species that possess intra-vertebral autotomy have pre-formed fracture planes within a series of tail vertebrae– the post-pygal vertebrae13,14. Preceding the post-pygal vertebrae within the tail are a series of non-autotomising vertebrae – the pygal vertebrae – that are associated with the attachment of the caudifemoralis longus muscle (CFL), as well as the muscles of the intromittent organs of males15,16,17,18,19. When relying on caudal autotomy to survive a threat, a lizard needs to drop a sufficient amount of its tail to distract the threat, but not so much that it incurs unnecessary costs – a balance known as the economy of autotomy4,20. As such, the number and position of caudal vertebrae with fracture planes will physically influence the effectiveness of caudal autotomy as an anti-predation strategy, the time and energy investment required to regenerate the tail, and the number of consecutive times caudal autotomy events can occur4,5. Phylogenetically the osteological features that allow for caudal autotomy can be lost or restricted within whole families or in species within families5,13. Although there are species and clades of lizards that cannot autotomise due to having tails with a specialised function (e.g., prehensility), there does not seem to be a clear phylogenetic pattern across lizards as a whole13,14,21.

Selective forces associated with predation risk can also lead to fracture planes being lost in certain species ontogenetically as the individual grows4,5. The degree in which fracture planes are lost varies across species from partial to complete loss4,13, and is likely influenced by the importance of the tail to each species as an adult5,21. Loss of fracture planes occurs through a fusion of the fracture plane within the caudal vertebrae, commencing dorsally from the neural arch extending ventrally toward the centrum, and extending proximally from the most distal vertebrae in the tail13. Predation risks faced by juvenile lizards are generally higher than those faced by adults; therefore, reliance on caudal autotomy is more adaptive for juveniles. For example, juveniles of certain species have evolved bright or contrasting colour patterns and/or different behaviours to that of adults to deflect attacks toward the tail, increasing the adaptiveness of caudal autotomy22,23,24,25. Conversely, adults show a greater ability to defend themselves physically against certain predators (e.g., some species of snake) due to their larger size and alternative defensive tactics14,25,26,27, avoiding costs associated with caudal autotomy.

The King’s skink (Egernia kingii) is a large skink endemic to the South-West of Western Australia and adjacent islands28,29. During ontogenetic development, E. kingii matures from small, gracile juveniles (7 g, SVL 60–80 mm) into large, robust adults (between 220 and 360 g, up to 244 mm SVL)28,30,31. Juvenile E. kingii are known to rely more heavily on caudal autotomy for survival than do adults24, with adults physically able to defend themselves against certain predators26,32. Egernia kingii belong to the lygosomine ‘Egernia group’, a small but diverse grouping of ~ 50 skink species across seven genera that have either lost their autotomy planes evolutionarily (E. depressa and E. stokesii) or ontogenetically (Corucia zebrata, Tiliqua rugosa and T. scincoides), or have retained autotomy planes as adults (E. cunninghami, Liopholis inornata, T. gigas and T. nigrolutea)13,14,16,17. The ‘Egernia group’ include both gracile and largely robust species ranging between 70-270 mm SVL as adults and have multiple species with different tail specialisations (e.g., C. zebrata’s semi prehensility, and T. rugosa’s fat storage)29,33. However, unlike some of the ‘Egernia group’ species, E. kingii is not known to have additional caudal specialisations beyond autotomy, and, as such, ontogenetic changes of caudal autotomy planes can be approached purely from an anti-predation perspective. Additionally, as E. kingii are a slow-maturing (3–5 years), long-lived (suspected ~ 20 years) species30,33, potential ossification of fracture planes has a longer ontogenetic time frame to occur compared to that of a short-lived species.

We predict that fracture planes would be lost or restricted in Egernia kingii as they age and change from gracile, autotomy-reliant animals to robust animals that are able to rely on other physical defence tactics14. In this study, we use 1) micro-computer tomography to investigate the caudal morphology of E. kingii, 2) identify the pattern and degree of fracture planes present, and 3) assess if the fracture planes are lost or restricted ontogenetically to certain regions of the tail. The use of a growth series in this context instead of comparing a single juvenile and adult individual allows for a more in-depth investigation of how ossification occurs ontogenetically over the lifespan of E. kingii. We provide valuable insight into how the importance of this anti-predation strategy changes morphologically during ontogeny, and discuss the potential implications of the change both within E. kingii and in other lizard taxa with alternative methods for balancing costs of anti-predation strategies to maximise their effectiveness.

Results

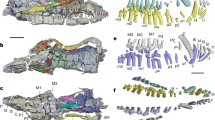

The micro-CT scans of the seven E. kingii specimens representing a growth series (SVL 132 mm–205 mm) reported in Table 1 show that intra-vertebral fracture planes were present in all specimens examined. Autotomy planes were not lost from, or restricted to, certain regions of the tail across the growth series, with fracture planes being evident in both the neural arch and centrum of the post-pygal vertebrae for all specimens examined (Fig. 1). The total number of post-pygal vertebrae ranged from 39—44 vertebrae, with an average (± SD) of 41 ± 2. The first 5–6 caudal vertebrae lacked fracture planes (pygal vertebrae), with the start of the post-pygal series of vertebrae (i.e., those with autotomy planes) at either the 6th or 7th caudal vertebra. The total number of caudal vertebrae in the E. kingii specimens ranged from 44 to 50, with an average (± SD) of 46 ± 2.

Sagittal longitudinal sections of Egernia kingii caudal vertebrae from reconstructed micro-CT images showing fracture planes (arrows) in the neural arch (top arrows) and centrum (bottom arrows). Images for a juvenile (top row) specimen (R62232) and an adult (bottom row) specimen (RI adult). Pygal vertebra without fracture planes and post-pygal vertebrae with fracture planes at proximal, middle, and distal positions of the tail (a., b., c., d. for the juvenile and e., f., g., h for the adult). White bar represents 5 mm for the individual specimens.

Discussion

Ossification of fracture planes in the post-pygal vertebrae is the most common change associated with ontogenetic loss of autotomy in lizards4,13,14, and has been attributed to the greater relative importance of the tail after attaining a larger size, where tail loss would incur high costs to the individual4,14. Our results show that, for E. kingii, caudal autotomy fracture planes are not lost or restricted to a portion of the tail ontogenetically, with all specimens assessed from the ontogenetic growth series possessing intra-vertebral fracture planes throughout their post-pygal vertebrae. Although juvenile E. kingii rely heavily on caudal autotomy24, the complete retention of fracture planes and the ability to autotomise their tails as adults likely indicate that a net benefit from autotomy still applies to mature individuals1,12,14,18.

Caudal autotomy, although often thought of as primarily an anti-predation strategy, can be beneficial to survival for interactions with non-predatory threats and therefore be retained even in the absence of predators34. Both intra- and inter-specific aggressive interactions, often exacerbated in denser populations such as those occurring on islands, can result in tail loss in lizards for adults and juveniles35,36,37. For example, increased tail break frequencies in adult Mediodactylus kotschyi (Gekkonidae) was correlated with higher gecko abundance but not predator richness across island populations34. In Anolis nebulosus (Dactyloidae), increased frequencies of caudal autotomy were correlated with inter-and intra- species aggression for both adults and juveniles across mainland and island populations35. The distribution of E. kingii occurs throughout the South-West of Western Australia, including multiple offshore islands28,29. Some offshore islands, like Penguin Island, are free of terrestrial predators and E. kingii occur in high densities – up to 667–950 individuals/ha38,39,40. Non-predatory aggressive interactions are evident between adult lizards, especially during the mating period, and from nesting shorebirds (J. Barr, pers obs). Therefore, the retention of caudal autotomy in adults could be of potential benefit to individuals exposed to high levels of intra- or inter-specific aggression5,34,41.

For adult lizards, tail loss can have significant negative effects on the reproductive output of an individual. Tail loss can result in reduced mate attraction or mating success42,43, physical loss of caudal fat reserves vital in vitellogenesis and young development9,44,45, and decreased likelihood of reaching future reproductive seasons due to increased predation risk46,47,48. Tail loss during the reproductive season can reduce litter size, the number of young produced, and even skipping reproduction, especially in species that use their tails for fat storage9,49. Short-lived species have fewer reproductive seasons over their lifespan than long-lived species, particularly if they are missing their tail, and therefore rendered more vulnerable to predation. If autotomy occurs during the reproductive season, the reproductive output should be prioritised in short-lived species through energy investment into reproduction over regeneration, with long-lived species prioritising regeneration and survival for future reproductive seasons8. Egernia kingii is a slow-maturing (3–5 years), long-lived species, with a breeding season restricted to approximately two months in the Austral spring and summer30,33. Adults are likely to live upwards of 15–20 years, similar to the related E. cunninghami33, giving them a longer reproductive span compared to short-lived, fast-maturing species. Ontogenetic retention of caudal autotomy planes may allow E. kingii to balance the reproductive costs of caudal autotomy as adults through their longevity and future reproductive seasons, with retention of this nascent strategy serving as a last resort scenario and conveying an overall fitness benefit to the species12.

Behavioural decisions, including anti-predation strategies, are largely influenced by the perception or recognition of a threat50,51,52,53,54. Behavioural responses to threat perception and associated anti-predation behaviour can be learned or lost over time with exposure to or isolation from threats54,55,56,57,58. Both frequency and ease of caudal autotomy for lizards often increase in high threat environments41,59. Intra-vertebral caudal autotomy is under the conscious control of the individual, and active muscular contractions of the tail assist in breakage at the fracture plane, hence physical stimulus from a potential predator is not necessarily required18,60,61. The ability of the individual to regulate when and how much of its tail is autotomised may, especially within changing environments, confer a fitness benefit while minimising associated costs (e.g., dropping and regenerating a part of, as opposed to the entire tail) and hence the retention of caudal autotomy into adulthood.

Balancing the fitness costs and benefits of caudal autotomy in lizards has seen loss or restriction of fracture planes between clades and throughout ontogeny, with no clear phylogenetic pattern evident. Ontogenetic fitness costs, at least in intra-vertebral autotomising lizard species, may be mitigated through behavioural regulation and the species’ longevity. This would allow for the retention of caudal autotomy and its benefits as adults (e.g., to escape from potential threats if required) and reduce the potential long-term negative fitness effects, particularly those associated with reduced reproductive output. Here we show that caudal fracture planes are not lost or restricted during ontogenetic development of the large, long-lived skink Egernia kingii and suggest how fitness costs are likely to be balanced to allow for their retention. Additionally, the CT scanning analysis presented in this paper provides a non-destructive, powerful approach to examine in detail the fracture plane in a variety of preserved specimens. This approach will be very useful in examining the interaction between fracture plane loss and balancing the metabolic costs of regeneration.

Methods

Specimens

Seven preserved E. kingii specimens representing a juvenile to adult growth series (SVL 132 mm–205 mm) were chosen to investigate the ontogenetic change in caudal osteology and fracture planes. Six preserved E. kingii specimens came from the Western Australian Museum (WAM) (R61436, R62232, R78064, R84662, R132059 & R151388) and one recently deceased specimen from Rottnest Island (RI), donated by the Rottnest Island Authority (RIA). The specimen obtained from RIA was frozen at − 20 °C and preserved in 100% ethanol. Western Australian Museum specimens were formalin-fixed and stored in 70% ethanol. Specimens were selected based on the criteria of (1) being in good condition, (2) having their original tail intact (no regeneration) as determined from visual inspection, and (3) that preservation had not made specimen rigid, allowing easy manipulation during micro-CT scanning. Snout to vent length (SVL) and tail length (TL) of specimens was measured to the nearest mm using a flexible fabric measuring tape. The number of autotomisable vertebrae was obtained by visual confirmation of fracture plane presence from micro-CT images in the neural arch and centrum.

CT scanning and analysis

Sample specimens were scanned individually using a SkyScan 1176 scanner (Bruker micro-CT, Kontich, Belgium) at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation and Analysis (CMCA), University of Western Australia. The CT scans were performed at 18 μm resolution (65 kV, 385µA, 300 ms, 1 mm Al filter, 0.5° rotation step, no frame averaging, 360° scan) producing 2000 * 1336-pixel images. Scanning images were reconstructed in NRecon v1.7.1.0 (Bruker micro-CT) using the modified Feldkamp cone-beam algorithm (Gaussian smoothing kernel (2), ring artefact correction (20), beam hardening correction (30%) and threshold for defect pixel masking (0–5%)). Three-dimensional models were constructed and manipulated in Avizo 2019.4 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The caudal vertebral column of all specimens was examined using coronal and sagittal longitudinal sections from the Ortho Slice function, with the presence or absence of an autotomy plane in the centrum and neural arch marked as being present or absent (see Fig. 1).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or after the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Emberts, Z., Escalante, I. & Bateman, P. W. The ecology and evolution of autotomy. Biol. Rev. 94, 1881–1896. https://doi.org/10.1111/brv.12539 (2019).

Dunoyer, L. A., Seifert, A. W. & Van Cleve, J. Evolutionary bedfellows: Reconstructing the ancestral state of autotomy and regeneration. J. Exp. Zool. Part B Mol. Dev. Evol. 336, 94–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/jez.b.22974 (2021).

Dial, B. E. & Fitzpatrick, L. C. Lizard tail autotomy: function and energetics of postautotomy tail movement in Scincella lateralis. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.219.4583.391 (1983).

Arnold, E. Caudal autotomy as a defense. Biol. Reptil. 16, 235–273 (1988).

Bateman, P. W. & Fleming, P. A. To cut a long tail short: A review of lizard caudal autotomy studies carried out over the last 20 years. J. Zool. (Lond.) 277, 1–14 (2009).

Woodland, W. Memoirs: Some observations on caudal autotomy and regeneration in the gecko (Hemidactylus flaviviridis, Rüppel), with notes on the tails of Sphenodon and Pygopus. J. Cell Sci. 2, 63–100 (1920).

Alibardi, L. Morphological and Cellular Aspects of Tail and Limb Regeneration in Lizards: A Model System with Implications for Tissue Regeneration in Mammals (Springer, 2010).

Maginnis, T. L. The costs of autotomy and regeneration in animals: A review and framework for future research. Behav. Ecol. 17, 857–872. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arl010 (2006).

Dial, B. E. & Fitzpatrick, L. C. The energetic costs of tail autotomy to reproduction in the lizard Coleonyx brevis (Sauria: Gekkonidae). Oecologia 51, 310–317. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00540899 (1981).

Vitt, L. J., Congdon, J. D. & Dickson, N. A. Adaptive strategies and energetics of tail autotomy in Lizards. Ecology 58, 326–337. https://doi.org/10.2307/1935607 (1977).

Clause, A. R. & Capaldi, E. A. Caudal autotomy and regeneration in lizards. J. Exp. Zool. 305, 965–973 (2006).

Barr, J. I., Boisvert, C. A. & Bateman, P. W. At what cost? Trade-offs and influences on energetic investment in tail regeneration in lizards following autotomy. J. Dev. Biol. 9, 53 (2021).

Etheridge, R. Lizard caudal vertebrae. Copeia, 699–721 (1967).

Arnold, E. Evolutionary aspects of tail shedding in lizards and their relatives. J. Nat. Hist. 18, 127–169 (1984).

Zani, P. A. Patterns of caudal-autotomy evolution in lizards. J. Zool. (Lond.) 240, 201–220 (1996).

Russell, A. & Bauer, A. The m. caudifemoralis longus and its relationship to caudal autotomy and locomotion in lizards (Reptilia: Sauria). J. Zool. (Lond.) 227, 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04349.x (1992).

Arnold, E. Investigating the evolutionary effects of one feature on another: Does muscle spread suppress caudal autotomy in lizards?. J. Zool. (Lond.) 232, 505–523. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1994.tb01591.x (1994).

Bellairs, A. & Bryant, S. Autotomy and regeneration in reptiles. Biol. Reptil. 15, 301–410 (1985).

Hoffstetter, R. & Gasc, J. P. Vertebrae and ribs of modern reptiles. Biol. Reptil. 1, 201–310 (1969).

Cooper, W. E. Jr. & Frederick, W. G. Predator lethality, optimal escape behavior, and autotomy. Behav. Ecol. 21, 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arp151 (2009).

Fleming, P. A., Valentine, L. E. & Bateman, P. W. Telling tails: Selective pressures acting on investment in lizard tails. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 86, 645–658 (2013).

Bateman, P. W., Fleming, P. A. & Rolek, B. Bite me: Blue tails as a ‘risky-decoy’defense tactic for lizards. Curr. Zool. 60, 333–337 (2014).

Hawlena, D., Boochnik, R., Abramsky, Z. & Bouskila, A. Blue tail and striped body: Why do lizards change their infant costume when growing up?. Behav. Ecol. 17, 889–896. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/arl023 (2006).

Barr, J. I., Somaweera, R., Godfrey, S. S. & Bateman, P. W. Increased tail length in the King’s skink, Egernia kingii (Reptilia: Scincidae): An anti-predation tactic for juveniles?. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 126, 268–275 (2019).

Pafilis, P. & Valakos, E. D. Loss of caudal autotomy during ontogeny of Balkan Green Lizard, Lacerta trilineata. J. Nat. Hist. 42, 409–419 (2008).

Masters, C. & Shine, R. Sociality in lizards: family structure in free-living King’s Skinks Egernia kingii from southwestern Australia. Aust. Zool. 32, 377–380 (2003).

Cury de Barros, F., Eduardo de Carvalho, J., Abe, A. S. & Kohlsdorf, T. Fight versus flight: The interaction of temperature and body size determines antipredator behaviour in tegu lizards. Anim. Behav. 79, 83–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.10.006 (2010).

Storr, G. The genus Egernia (Lacertilia, Scincidae) in Western Australia. Rec. West. Aust. Mus. 6, 147–187 (1978).

Cogger, H. G. Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. 7th edn, (CSIRO Publishing, 2014).

Arena, P. C. & Wooller, R. D. The reproduction and diet of Egernia kingii (Reptilia : Scincidae) on Penguin Island, Western Australia. Aust. J. Zool. 51, 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO02040 (2003).

Dilly, M. L. Factors Affecting the Distribution and Variation in Abundance of the King's Skink (Egernia kingii) (Gray) in Western Australia, Murdoch University (2000).

Pearson, D., Shine, R. & How, R. Sex-specific niche partitioning and sexual size dimorphism in Australian pythons (Morelia spilota imbricata). Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 77, 113–125 (2002).

Chapple, D. G. Ecology, life-history, and behaviour in the Australian scincid genus Egernia, with comments on the evolution of complex sociality in lizards. Herpetol. Monogr. 17, 145–180. https://doi.org/10.1655/0733-1347(2003)017[0145:ELABIT]2.0.CO;2 (2003).

Itescu, Y., Schwarz, R., Meiri, S., Pafilis, P. & Clegg, S. Intraspecific competition, not predation, drives lizard tail loss on islands. J. Anim. Ecol. 86, 66–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12591 (2017).

Siliceo-Cantero, H., Zúñiga-Vega, J., Renton, K. & Garcia, A. Assessing the relative importance of intraspecific and interspecific interactions on the ecology of Anolis nebulosus lizards from an island vs. a mainland population. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 12, 673–682 (2017).

Langkilde, T. & Shine, R. Interspecific conflict in lizards: Social dominance depends upon an individual’s species not its body size. Austral Ecol. 32, 869–877 (2007).

Pafilis, P., Pérez-Mellado, V. & Valakos, E. Postautotomy tail activity in the Balearic lizard, Podarcis lilfordi. Naturwissenschaften 95, 217–221 (2008).

Browne, C. King's Skinks (Egernia kingii) Abundance and Juvenile Survival Unaffected by Temporal Change or Presence of Invasive BLACK Rats (Rattus rattus) on Penguin Island, Western Australia, The University of Western Australia (2014).

Langton, J. Population Biology of the King's Skink (Egernia kingii) (Gray) on Penguin Island, Western Australia, Murdoch University (2000).

Arena, P. Aspects of the Biology of the King's Skink Egernia kingii (Gray), Murdoch University (1986).

Pafilis, P., Meiri, S., Foufopoulos, J. & Valakos, E. Intraspecific competition and high food availability are associated with insular gigantism in a lizard. Naturwissenschaften 96, 1107–1113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00114-009-0564-3 (2009).

Martín, J. & Salvador, A. Tail loss reduces mating success in the Iberian rock-lizard, Lacerta monticola. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 32, 185–189 (1993).

Salvador, A., Martin, J. & López, P. Tail loss reduces home range size and access to females in male lizards, Psammodromus algirus. Behav. Ecol. 6, 382–387. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/6.4.382 (1995).

Smyth, M. Changes in the fat scores of the skinks Morethia boulengeri and Hemiergis peronii (Lacertilia). Aust. J. Zool. 22, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1071/ZO9740135 (1974).

Wilson, R. S. & Booth, D. Effect of tail loss on reproductive output and its ecological significance in the skink Eulamprus quoyii. J. Herpetol. 32, 128–131 (1998).

Fox, S. F. & McCoy, J. K. The effects of tail loss on survival, growth, reproduction, and sex ratio of offspring in the lizard Uta stansburiana in the field. Oecologia 122, 327–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420050038 (2000).

Dial, B. E. & Fitzpatrick, L. C. Predator escape success in tailed versus tailless Scinella lateralis (Sauria: Scincidae). Anim. Behav. 32, 301–302 (1984).

Downes, S. & Shine, R. Why does tail loss increase a lizard’s later vulnerability to snake predators?. Ecology 82, 1293–1303 (2001).

Bernardo, J. & Agosta, S. J. Evolutionary implications of hierarchical impacts of nonlethal injury on reproduction, including maternal effects. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 86, 309–331 (2005).

Stankowich, T. & Blumstein, D. T. Fear in animals: A meta-analysis and review of risk assessment. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. Ser. B 272, 2627–2634. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2005.3251 (2005).

Steindler, L. A., Blumstein, D. T., West, R., Moseby, K. E. & Letnic, M. Exposure to a novel predator induces visual predator recognition by naïve prey. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 74, 102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-020-02884-3 (2020).

Blumstein, D. T. Moving to suburbia: Ontogenetic and evolutionary consequences of life on predator-free islands. J. Biogeogr. 29, 685–692. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2699.2002.00717.x (2002).

Sih, A. et al. Predator–prey naïveté, antipredator behavior, and the ecology of predator invasions. Oikos 119, 610–621 (2010).

Cooper, J. W. E.; Blumstein, D. T. Escaping From Predators: An Integrative View of Escape Decisions. (Cambridge University Press, 2015).

Cox, J. G. & Lima, S. L. Naiveté and an aquatic–terrestrial dichotomy in the effects of introduced predators. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 674–680 (2006).

Blumstein, D. T. & Daniel, J. C. The loss of anti-predator behaviour following isolation on islands. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. Ser. B 272, 1663–1668 (2005).

Blumstein, D. T., Daniel, J. C. & Springett, B. P. A test of the multi-predator hypothesis: Rapid loss of antipredator behavior after 130 years of isolation. Ethology 110, 919–934 (2004).

Jolly, C. J., Webb, J. K. & Phillips, B. L. The perils of paradise: An endangered species conserved on an island loses antipredator behaviours within 13 generations. Biol. Lett. 14, 20180222 (2018).

Cooper, W. E., Pérez-Mellado, V. & Vitt, L. J. Ease and effectiveness of costly autotomy vary with predation intensity among lizard populations. J. Zool. 262, 243–255 (2004).

Elwood, C., Pelsinski, J. & Bateman, B. Anolis sagrei (Brown Anole). Voluntary autotomy. Herpetol. Rev. 43, 642–642 (2012).

Slotopolsky, B. Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Verstümmelungs-und Regenerationsvorgänge am Lacertilierschwanze. Zool. Jahrb. Abt. Anat. Ontog. Tiere 43, 39–48 (1922).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the people of the Noongar nation, their Elders, past, present and emerging, as the traditional custodians of this country, on whose land this research was carried out. We want to thank the Western Australian Museum for access to their preserved collections, specifically Rebecca Bray, for her assistance with sample preparation and exploratory radiographic work (not presented here). This project was funded by the Holsworth Wildlife Research Endowment – Equity Trustees Charitable Foundation & the Ecological Society of Australia. The authors acknowledge the facilities, and the scientific and technical assistance of the National Imaging Facility at the Centre for Microscopy, Characterisation & Analysis, the University of Western Australia, a facility funded by the University, State and Commonwealth Governments. Specifically, the authors would like to thank Diana Patalwala and Jeremy Shaw for their contributions. This work was supported by resources provided by the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre with funding from the Australian Government and the Government of Western Australia. J.I.B. was supported by an RTP scholarship from the Australian Government, as well as a CRS scholarship and Inclusion Fellowship from Curtin University. CAB is supported by a Curtin Research Fellowship and a ROC research grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.I.B. was involved in the concept/design, acquisition of data, data analysis/interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article. P.W.B. was involved with concept/design, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article. C.A.B. was involved in concept/design, acquisition of data, data analysis/interpretation, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article. K.T. was involved in concept/design, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and approval of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Barr, J.I., Boisvert, C.A., Trinajstic, K. et al. Ontogeny and caudal autotomy fracture planes in a large scincid lizard, Egernia kingii. Sci Rep 12, 7051 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10962-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10962-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.