Abstract

The photodeposition of metallic nanostructures onto ferroelectric surfaces could enable new applications based on the assembly of molecules and patterning local surface reactivity by enhancing surface field intensity. DCJTB (4-(dicyanomethylene)-2-t-butyl-6-(1,1,7,7-tetramethyljulolidyl-9-enyl)-4H-pyran) is an excellent fluorescent dye and dopant material with a high quantum efficiency used for OLED displays on the market. However, how to raise the photoluminescence (PL) and reduce the lifetime of DCJTB in a substrate remain extraordinary challenges for its application. Here, we demonstrate a tunable ferroelectric lithography plasmon-enhanced substrate to generate photo-reduced silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and achieve enhanced PL with a shortened lifetime depending on the substrate’s annealing time. The enhanced PL with shortened lifetimes can attribute to the localized electromagnetic (EM) wave produced by the nanotextured AgNPs layers' surface and gap plasmon resonances. The simulation is based on the three-dimensional finite element method to explain the mechanism of experimental results. Since the absorption increases, the remarkable enhanced PL of DCJTB can attain in the fabricated periodically proton exchanged (PPE) lithium niobate (LiNbO3) substrate. Furthermore, the proposed fabrication method demonstrates to help tune the surface EM wave distribution in the substrate, which can simultaneously achieve the significantly shortened lifetime and high PL intensity of DCJTB in the substrate. Compared with the un-annealed substrate, the PL intensity of DCJTB in the assembly metallic nanostructures is enhanced 13.70 times, and the PL’s lifetime is reduced by 12.50%, respectively. Thus, the fabricated substrate can be a promising candidate, verifying chemically patterned ferroelectrics' satisfaction as a PL-active substrate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The presence of metal nanoparticles (MNPs) arranged in nanostructure offers a strong light-matter interaction resulting in “hot spots” with intensely large electromagnetic (EM) waves due to the structure’s plasmonic effect1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The concentration of high EM wave in the plasmon-enhanced substrate can widely apply for surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and other applications in nanophotonics18,19,20,21, and notably in applications requiring high wavelength sensitivity and selectivity22,23,24. The fabrication of functional nanomaterials with different MNPs in the plasmon-enhanced substrate called photoluminescence (PL) substrates has attracted considerable attention25,26,27,28,29. Several fabrication techniques include lithography-based techniques, such as holographic lithography30,31, focused ion beam patterning32,33, direct imprint34, nanosphere lithography35,36, thermal dewetting37, electron beam lithography38,39 and neutral beam etching40. These methods can produce high-quality arrays of plasmon-enhanced substrates; however, the processes are highly time-consuming and expensive because of the equipment's capital cost. Their reproducibility rate can be low41,42,43,44.

Recently, ferroelectric materials, e.g., lithium niobate (LiNbO3), as templates for the "growth" of patterned or structured MNPs has received numerous attention. It drives by the increasing demand for plasmon-enhanced substrates in the fields of biochemical sensors or reconfigurable electronics26,45,46,47,48. The solitary characteristics of ferroelectric surfaces can obtain electrowetting49,50, nanostructured surface functionalization, and localized chemical reactions51, especially in the use of localized charge transfer oxidation–reduction chemical processes capable of producing nanostructures of MNPs on the surface of ferroelectric substrates52. These substrates can serve as functional substrates for congregating complex nanostructures that combine with their surface electronic features. MNP fabrication on LiNbO3 ferroelectric surfaces can process using a photochemical reaction53. Ferroelectric lithography is an emerging technology that sanctions directed self-assembly. This technique has the potential in cost-cutting of MNP arrays production54. One of the potential techniques utilizes congruent single-crystal LiNbO3 as the ferroelectric template52. LiNbO3 has the merit of a single 180°-domain structure and reveals a powerful photovoltaic effect along the + z direction, in which the photoinduced electrons can migrate adequately55. When an ultra-violet (UV) light (~ 4.89 eV) impinges on the LiNbO3 (bandgap ~ 3.9 eV), electron–hole pairs can produce in the LiNbO3. The periodically modulated spontaneous polarization separates the electrons and holes, and the electrostatic field accelerates the electrons (photoelectrons) to the proton exchanged region surface. In the presence of the AgNO3 solution, the silver (Ag) ions can also speed up by the electrostatic field to the surface of the proton exchanged region, and the photoelectrons then diminish them to form a silver nanoparticle (AgNP) array56. It is, therefore, easy to deposit on the substrate by only utilizing the photovoltaic effect. Ag deposition occurs at the domain boundaries57.

There are several methods in producing plasmon-enhanced substrates. The physical mechanism on the enhanced fluorescence and shorter lifetime has been interpreted by Chen et al58. Wang et al. explained the mechanism of the direction of polarization in the LiNbO3 substrate and elucidated the photoelectrons migrating to the substrate surface can reduce the Ag ions59. Rodriguez et al. proposed a chemical patterning method to prepare the periodical proton exchanged (PPE) LiNbO353, and they claimed that the PPE LiNbO3 substrates have a stronger SERS signal due to the SPR effects60. However, the PPE LiNbO3 substrates reveal surface morphology in the range of 6–8 nm along the z-direction61, which could be a drawback for SERS application. Subsequently, Damm, S. et al. fabricated Ag nanopatterns using periodically poled LiNbO3 and periodically proton-explanted template methods60. Liu et al. reported on the fabrication of large-scale nanoparticle arrays SERS substrates based on periodically poled LiNbO3 templates55. Tseng et al. proposed a template with color surface plasmon-enhanced PL of organic dyes using annealed AgOx thin Film62. Ferroelectric lithography potentially provides a route to fabricate substrates that offer reproducible plasmon-enhanced substrates made from the MNP arrays of AgNPs53. For the benefits of expediency and reproducibility, photochemically deposited MNPs on ferroelectric-based substrates have great potential in surface-plasmon-related applications63.

OLED (Organic light-emitting devices), as an exemplary flat panel display and solid-state lighting source, have attracted numerous considerations since their advantages are low cost, low consumption, and environment-friendly64. An archetypical dopant material used for many of today’s OLED displays on the market is DCJTB (4-(dicyanomethylene)-2-t-butyl-6-(1,1,7,7-tetramethyljulolidyl-9-enyl)-4H-pyran), which is an excellent red fluorescent dye with solution PL λmax ~ 620 nm and a quantum efficiency > 90%65. Still, to improve the PL and diminish the lifetime of DCJTB in a substrate, endure significant challenges for its commercialization application. While several types of research have demonstrated that a range of metallic nano- and microstructures can make using ferroelectric lithography61,66, few studies have applied such structures to simultaneously enhance the PL intensity and reduce the lifetime of the DCJTB in a substrate. Unlike the substrates mentioned above, this paper proposed a PL-active substrate with a high PL intensity and a short PL’s lifetime of the DCJTB depending on the substrate’s annealing time. We use an inexpensive and easily controlled method to fabricate plasmon-active PPE LiNbO3 templates and verify the functionality of the substrate by depositing AgNPs onto the substrates. Furthermore, the chemical patterning used by the proposed procedure offers the capability to manipulate the EM waves in the vicinity of LiNbO3 crystals’ surface. Thus, we can simultaneously achieve the remarkable enhanced PL intensity and short PL’s lifetime of DCJTB in the fabricated plasmon-enhanced substrate system. To understand the mechanism, we employ the three-dimensional (3-D) finite element method (FEM) on the dependence of EM wave distribution. The proposed substrate results from surface plasmon resonance (SPR), gap plasmon resonance (GPR), and the confined local EM wave. The substantial plasmonic enhancement makes the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate a promising candidate for function as a PL-active substrate.

Fabrication procedure

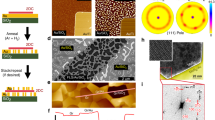

The PPE LiNbO3 shows a lesser density of defects in the vicinity of its surface, which leads to remarkably external screening and nearly flat bands close to the surface43,55. PPE LiNbO3 substrate can fabricate by electric poling. The LiNbO3 single crystal wafer is first to cut perpendicular to the crystallographic c-axis and polished67. This paper reports on the main procedures in fabricating flat PPE LiNbO3 substrates and the assembly of AgNPs onto the + z domain surfaces of LiNbO3. We utilize the nanoscale patterned consistent LiNbO3 as the deposition substrates. Figure 1a–j depict the PPE LiNbO3 substrate's fabrication procedures. The z-cut with the dimension of 0.8 cm × 0.8 cm × 1 mm of ferroelectric substrates (optical grade, congruent LiNbO3 substrates, Crystal Technology Inc.) was adopted to fabricate the PPE LiNbO3 substrates. Firstly, the substrate was cleaned using acetone and methanol in an ultrasonic bath for 20 min and then heated on a hot plate at 120 °C for 3 min (Fig. 1a). Subsequently, we deposited a 240 nm-thick Chromium (Cr) film (which uses as a proton exchanged mask) on the substrate surface with a 40 W RF magnetron sputtering under the pressure of 0.6 Pa and Ar flux of 30 sccm for 30 min (Fig. 1b). An SPR6810 photoresist layer was then spin-coated onto the cleaned substrate surface (Fig. 1c). The resulting substrate was heated on a hot plate at 95 °C for 1.5 min. We covered the LiNbO3 substrate surface with a periodic Cr-mask patterned via photomask aligner and D-35 developer solution for the photolithography process. An ultraviolet (UV) light with an incident wavelength of 254 nm impinged the substrate for 20 s. We reduced the Cr film's photoresist stripes after heating by a hot plate at 140 °C for 3 min (Fig. 1d). The substrates were then put in an oven at 120 °C for 30 min. After that, we removed the Cr film (which was uncovered by the photoresist mask) using an etching solution and then removed the photoresist using acetone. After photolithography and wet etching, the formed Cr film used as the proton exchanged mask has an opening width of 5.0 μm and a period of 10.0 μm. The Cr mask formed by PPE LiNbO3 substrate was then obtained (Fig. 1e). Subsequently, the PPE LiNbO3 substrate was immersed in a proton-rich benzoic acid melt at 200 °C for 24 h (Fig. 1f). After that, we cleaned the PPE LiNbO3 substrate and removed the patterned Cr film (Fig. 1g). Edwin et al. have found that the cause of annealing on the surface index change and the waveguide depth increase follows a power-law relationship68. Therefore, the substrates were annealed at 240 °C for 1 h, 4 h, 9 h, and 16 h for comparison (Fig. 1h). We cleaned the PPE LiNbO3 substrates, and then AgNPs deposition was carried out by dripping the 10–2 M aqueous solution of AgNO3 on the domain patterned LiNbO3 crystal surface under UV irradiation (with the incident wavelength of 254 nm) for 3 min at 2 cm (Fig. 1i). When the LiNbO3 surface is covered with a metal salt solution such as AgNO3 and irradiated by a UV light, the electrons can be quickly induced and migrated toward the positive direction since the band bending energy. The photoelectrons migrating to the substrate surface reduce the Ag ions in the solution to form the AgNPs layer. After UV irradiation, the substrate surface was rinsed with distilled water and then sprayed with nitrogen gas to dry it. After photodeposition, we obtained the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates (Fig. 1j).

Schematic illustrations of the fabrication procedures of a periodically proton-exchanged (PPE) LiNbO3 substrate, (a) clean substrate, (b) Cr film deposition, (c) spin coating SPR 6810, (d) photolithography, (e) Cr film etching, (f) photon exchange (200 °C, 24 h), (g) removing Cr film, (h) annealing (0, 1, 4, 9, 16) h, (i) photodeposition and (j) after photodeposition.

Figure 2 depicts the optical microscope (Carl Zeiss Axiolab) images of the PPE LiNbO3 substrates with the different annealing times of 0-h, 1 h, 4 h, 9 h, and 16 h before photoreduction (Fig. 2a) and after photoreduction (Fig. 2b). These optical microscope images reveal the brilliant lines represent the proton exchange regions. In the annealing procedure, the protons can diffuse along with both the out of plane and in-plane, respectively54. Therefore, the line width is widened as the annealing time (ta) increases for ta = 0 h and 4 h and shows the unapparent change for ta = 9 h and 16 h.

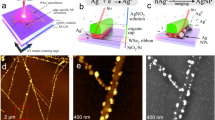

Figure 3a,b show the SEM images of photoreduced AgNPs using PPE LiNbO3 substrates made with various annealing time. As observed, the AgNPs can form in the proton exchanged zone and show a different width of demarcation under variant annealing times. Although the distribution of AgNPs also grows into dense with the increase of annealing time and the gaps of AgNPs become small, the size of AgNPs is approximately similar when ta = 9 and 16 h (Fig. 3b4,b5). For the substrate without annealing treatment (ta = 0 h), the number of AgNPs is not many, and most of them have a small size (see Fig. 3a1,b1). In Fig. 3a, the two broad lines on the proton exchanged area’s edges relate to the areas with larger AgNPs formed by the edge enhancement of the electrostatic field. As the annealing time increased (see Fig. 3a2–a5,b2–b5), the AgNPs’ size enlarges, and the number of large-size AgNPs grows into a larger area with the larger AgNPs shifting toward the proton exchanged area’s center54. This phenomenon demonstrates that the annealing process influences the size of the proton exchanged mask69.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of photoreduced AgNPs using PPE LiNbO3 substrates made with different annealing time, (a) with the magnification of 6 K and (b) with the magnification of 100 K, respectively. (c) Size-distribution histogram of the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates under different annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h.

Figure 3c depicts the size-distribution histogram of the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates under different annealing times. It can expect that the PPE LiNbO3 substrate without annealing treatment (ta = 0 h) generates smaller AgNPs in which the size does not reach 100 nm (see Fig. 3c1). As the annealing time increases, the electrostatic field enhanced by the ferroelectric PPE LiNbO3 substrate increases photoelectrons and Ag ions, creating more large-size AgNPs54,66,69. In the proposed plasmonic system, the absorption peak of localized surface plasmon resonance depends on the gap between adjacent AgNPs, the size and shape of the AgNPs. Among them, the gap between adjacent AgNPs will dominate the plasmonic effect in the fabricated substrates, and this effect was demonstrated by COMSOL Multiphysics simulations (see Fig. 8). We measured the size of AgNPs based on SEM images and histograms. The average diameter of AgNPs is around 45.60 nm, 55.40 nm, 58.39 nm, 63.00 nm, and 57.30 nm for different annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h, respectively. Note that the annealing time with 9 h has the largest average size of AgNPs and more AgNPs ranging in 30 ~ 100 nm than the other annealing time, exposing the larger surface of AgNPs in the same area. These results from Fig. 3b,c have correlated with the annealing time. The edge enhancement effect, which possesses more dipole effects (i.e., more positive–negative charge pairs on the Ag surface70,71,72,73,74), leads to the EM wave enhancement and helps form a different size of AgNPs depending on the various annealing time. It indicates that the ferroelectric PPE LiNbO3 substrate's EM wave enhancement can effectively increase the growth rate of AgNPs and facilitate the formation of large-size AgNPs. Figure 4 shows both the average size and the density of AgNPs (in 1 μm2) as a function of annealing time (hour). The annealing time with 9 h has the largest average size and the density of AgNPs compared to the other annealing time.

Measurement results and discussion

Optical density, denoted as log10 (1/T), increases with larger absorption excited by the localized SPR on the AgNPs’ surface. Figure 5a shows the optical density spectra of the fabricated substrate under various annealing time of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h, respectively. Two prominent optical density peaks for all cases occur around λ = 520 nm and λ = 665 nm, corresponding to two SPR modes of the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate. The first peak with the maximal optical density at 520 nm is near the measurement's excitation wavelength. The maximal peak value of optical density is ta = 9 h. The magnitude of optical density is strongly related to the localized SPR effect generated from the interaction between the incident EM wave and the AgNPs on the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate. The wavelength corresponds to the optical density peak of the fabricated substrate treated with different annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h. In Fig. 5a, the OD spectra do not show the size-dependent shift upon changing the annealing time since the average size of AgNPs shows a minor difference, and the size and distribution of AgNPs are not uniform. Therefore, the OD spectra reveal a broadband profile. Note that the intensity variation in the optical density's tendency with the annealing time is directly proportional to the AgNPs density, as mentioned above. This phenomenon indicates that the fabricated substrate with ta = 9 h shows the most plasmonic effect on the AgNPs’ surfaces compared to other annealing times. The case of ta = 0 h (i.e., non-annealed substrate) shows the smallest optical absorption because the smaller and lower density of AgNPs can produce on the fabricated substrate surface. Figure 5a shows that the density and distribution of AgNPs in the fabricated substrate greatly influence the plasmonic effect and optical absorption. Such remarkable enhancement is excited by plasmonic coupling between the AgNPs and incident EM wave. This result is direct evidence of AgNPs contributing to the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate's optical density performance. Furthermore, it is illustrated through the optical density spectrum that the AgNPs can confine surface plasmons if the gap between the adjacent AgNPs is sufficiently small.

The assembly of metallic nanostructures can further functionalize with a target molecule from detecting the Raman signal. If a target molecule is under the hot spot of the EM wave, it will generate a relatively large Raman signal from the target molecule. We used a laser confocal Raman microspectrometer (equipped with a 532 nm laser) to inspect the EM wave scattering of a target molecule. All measurements utilized a 20 × /NA0.4 objective, an R500-2000 line/mm grating, a data integration time of 5 s, and a small laser power set at 1 mW. Each substrate was subjected to ten measurements at different spots to obtain an average Raman signal. We used a representative organic analyte, rhodamine 6G (R6G), with 10–5 M as the target molecule for Raman signal measurement. R6G has well-established vibrational features and extensive surface-enhanced scattering properties. Figure 5b depicts the Raman spectra of the R6G dye on the flat LiNbO3 and the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates produced with different annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h. The various annealing time of the substrates exhibits tunable PL activities. It can observe that six distinct Raman intensity peaks appeared in the range of 800–1700 cm−1, which can contribute by the various vibration modes of the R6G molecules. The intensities of the R6G’s Raman peaks from the fabricated substrates are related to the interaction between the vibration modes and the localized surface plasmon mode. Such enhancement in Raman signals can attribute to the plasmonic effect arising from the surface plasmon on AgNPs, the gap plasmon enhancement among AgNPs, and the charges transfer between the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate and R6G. This result implies that one can get Raman signal enhancements using the most favorable photoreduced MNP nanostructure, i.e., the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates54. As discussed in Fig. 5a, we can tune the plasmonic effect by the different annealing times. As the annealing time changes, it can also alter the Raman signals' corresponding plasmonic response. Note that the optimal value of annealing time is ta = 9 h. It leads to enhanced E-field localization in the gap and edge regions among the AgNPs and the surface of the AgNPs. These effects are beneficial to improve the Raman signals. In Fig. 5b, the Raman peaks of the R6G dye occurs at the wavenumbers of 1181 cm−1, 1314 cm−1, 1365 cm−1, 1514 cm−1and 1661 cm−1, and it does not appear in the case of flat LiNbO3, which Raman peak is only happened at 866 cm−1 and exhibits the highest one compared to other annealing times. In these AgNPs-assisted plasmon-enhanced substrates, the weak Raman signal can collect at the flat LiNbO3 and ta = 0, 1, and 4 h with the smaller Raman peaks at 1181 cm−1, 1314 cm−1and 1661 cm−1, whereas stronger Raman signals can achieve at ta = 9 and 16 h with remarkably Raman peaks. The Raman peaks at 1365, and 1514 cm−1 demonstrated the generation of R6G dye produced by the fabricated plasmon-enhanced substrates when ta = 4, 9, and 16 h. The Raman signal intensity at 1365 cm−1 on the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate can assign to the aromatic C–C stretching of R6G molecule75. Figure 5b demonstrates that the Raman signal intensities increase with the increasing annealing time. The maximal intensity peak occurs at ta = 9 h, with the maximal plasmon-enhanced effect compared to the other annealing time. The plasmon-enhanced phenomenon is attributed to the most substantial electric field enhancement results from many closely adjacent, large-diameter AgNPs, as indicated in Fig. 3b4, with high-density inter-particle gaps in subwavelength scale, and thus more gap plasmon resonance effect. It is worth noting that the highest measured Raman peak of ta = 9 h at the wavenumber of 1365 cm−1 is enhanced 10.36 times compared to ta = 0 h (i.e., un-annealed substrate), exhibiting the noticeably improved sensitivity. The Raman intensity spectra obtained from the R6G molecules adsorbed on the various PPE LiNbO3 substrates can demonstrate the enhanced magnitude and scattering of the EM waves in the fabricated plasmon-enhanced substrates (i.e., the bright spots arising from the plasmonic effect).

For obtaining the PL spectra, 375 nm CW laser was employed to excite the DCJTB emission, whose absorption is around 510 nm76. Besides, the PL signal can be enhanced when the resonant mode of plasmonic nanoparticles is spectrally overlapped with either the absorption wavelength or the emission position of the photon emitters77,78. The excitation laser is away from the peak wavelength of the plasmonic modes in nanoparticles. However, the spectral overlapping between the plasmonic absorption and emitted photon energy can be obtained due to the relatively broad absorption spectrum (see Figs. 5a and 6). As a result, the observed PL enhancements are initially from the near-field coupling between the DCJTB and Ag nanoparticles. Note that the absorption peak at ~ 670 nm is another plasmonic mode, which occurs in all cases in Fig. 5a and contributes to enhancing the PL signal. The absorption at ~ 670 nm possesses almost equal intensity in all cases, further verifying that the sample-dependent PL enhancement is mainly from the broad plasmonic absorption centered at ~ 510 nm.

The localized SPR wavelength of AgNPs at 510 nm can couple well with the DCJTB molecular, thus leading to the plasmonic enhancement of the DCJTB emission. Figure 6 shows the PL measurement results of the flat LiNbO3 and the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates under various annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h. A CW laser light of 375 nm wavelength with a 0.4 mW power and an integration time of 1 s is transmitted through a mirror into an inverted microscope and focused onto the substrate via an objective lens with 0.9 NA and 100 × magnification. To prevent energy transfer quenching, we insert a SiO2 buffer between the substrate and the DCJTB fluorescent dye layer. The thickness of the SiO2 buffer layer and DCJTB is 10 nm and 75 nm, respectively, as discussed in our previous literature35,79. In Fig. 6, all the spectral profiles had similar shapes. The exposed area of the AgNPs surface can generate PL intensity enhancement because the increased PL intensity could be attributed to DCJTB molecules' interactions with the AgNPs surface, offering a plasmon resonance. A noticeable difference in PL intensity in Fig. 6 can observe under different annealing times. The PL intensity of the case of ta = 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h can reach a maximum value of 4699, 13,801, 18,343, 23,933, and 21,086, respectively, which are 2.69, 7.9, 10.5, 13.7, and 12.07 times the intensity compared to the flat LiNbO3 substrate.

Subsequently, we measured the lifetime of the dye molecules (DCJTB with 75 nm) for flat LiNbO3 substrate and the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates under different annealing times of 0, 1, 4, 9, and 16 h. The lifetime measurement method is reported in the previous works35,62,79. We used a laser beam (λ = 375 nm, power = 0.4 W) focused onto the substrate and performed a 2D XY-scan of 50 × 50 μm2 area with simultaneous time-resolved PL (TRPL) measurements and recorded the light intensities of each spot20,80. A biexponential function, I PL(t) = ∑Ai exp(− t/τi) + y0, is used to fit the measured PL decay curves. Where τi, Ai, and y0 denote decay time, amplitude, and background intensity, respectively35,62,81,82,83. For simplicity, the measured PL decay lifetime is given by 1/ τTRPL = 1/τ1 + 1/τ220.

In Fig. 7, the dye molecules' decay rates on the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates treated with annealing time are faster than the corresponding one without annealing and the flat LiNbO3 substrate. By combining all the luminescence spectrum areas and comparing the intensities from DCJTB on the PPE LiNbO3 substrates, the lifetime of 1.19 ns can be achieved under the annealing time, ta = 9 h. The rest of the lifetime for DCJTB substrate, ta = 0, 1, 4, and 16 h are 1.36, 1.35, 1.32, 1.30, and 1.26 ns, respectively. The lifetime at ta = 9 h is reduced by 12.50% (from 1.36 to 1.19) compared to DCJTB substrate. These results can be elucidated by the strong EM wave coupling when the substrate nanostructure's plasmon resonance overlaps with the molecules' absorption band35.

We used COMSOL Multiphysics simulations to understand the mechanism of electric field distribution on the surface of the proposed substrate. The simulations used a 3-D model with perfectly matched layer boundary conditions84. Since the case of ta = 9 h exhibits the most robust fluorescence than the other annealing time, we compare the two cases, ta = 9 h and ta = 0 h, in our simulation models. The sizes of simulation models are 875 nm(x) × 875 nm(y) × 60 nm(z) for the case of ta = 9 h and 875 nm(x) × 875 nm(y) × 40 nm(z) for the case of ta = 0 h, respectively. Circularly polarized light with an incident wavelength of 650 nm and electric field intensity of E0 = 1 V/m is launched normally from the top of the substrates. The permittivity data of Ag can obtain from Refs.85. The plasmonic effect can mainly contribute by enhancing of the localized surface plasmon acting on the nanostructure86,87,88,89. Figure 8a,b depict the simulated spatial electric field distribution induced by the incident light of 650 nm impinging on the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrate with ta = 0 h and ta = 9 h, respectively. The localized electric field in the vicinity of the AgNPs with the larger diameter and smaller gap distance under ta = 9 h is more vital than that of a smaller one under ta = 0 h. It is consistent with the above PPE's experimental results (Fig. 3c1,c4), which possess the maximum number of AgNPs in the diameter range of 30 ~ 100 nm, showing the most substantial absorption at 650 nm. The simulation result also displays a strong localized electric field in the gaps among AgNPs. The significant electric field enhancement around the large-diameter AgNPs and the small gap between AgNPs suggests the leading cause of the PL enhancement in the fabricated substrate. These results are relevant to PL-active substrates' design, and we can expect a larger PL with plasmon enhancement.

Conclusions

To summarize, we have demonstrated a reliable and relatively easy method to construct a plasmon-enhanced photoluminescence substrate with a shortened lifetime. We studied the DCJTB’s PL, and lifetime depending on the substrate's annealing time. The chemical patterning offers the capability to manipulate the EM waves near the surface of lithium niobate substrate, and these engineered fields can apply to fabricate the assembly of metallic nanostructures, which have a PL-active function. The PL intensities and shortened lifetimes of DCJTB in the fabricated substrate confirmed the presence of enhanced local EM waves by SPR and GPR modes, which are strongly confined on the substrate’s surfaces and in the AgNPs’ gaps. In the AgNPs-assisted photoreduction, enhancing the electrostatic field facilitates large-diameter AgNPs, and can achieve intense localized EM wave action by annealing time. 3D-FEM simulations demonstrated that the confined electric field around the AgNPs with larger size under ta = 9 h are more vital than weaker fields surrounding the smaller AgNPs under ta = 0 h. Compared with the un-annealed substrate, the fabricated PPE LiNbO3 substrates with ferroelectric AgNPs can enhance the PL intensities of DCJTB by 13.70 times and reduce the PL’s lifetime by 12.50% (from 1.36 to 1.19) at ta = 9 h, respectively. The fabricated ferroelectric PPE LiNbO3 substrates with the vigorous photoreduction characteristic promise versatile PL applications for practical optical device applications.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compelling reasons why data are not public but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chang, R., Chiang, H. P., Leung, P. T., Tsai, D. P. & Tse, W. S. Nonlocal effects in the optical response of composite materials with metallic nanoparticles. Solid State Commun. 133, 315–320. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssc.2004.11.014 (2005).

Chau, Y.-F.C. et al. Plasmonic effects in composite metal nanostructures for sensing applications. J. Nanopart. Res. 20, 190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-018-4293-4 (2018).

Chou Chau, Y.-F. et al. Perfect dual-band absorber based on plasmonic effect with the cross-hair/nanorod combination. Nanomaterials 10, 2030. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030493 (2020).

Kumara, N. T. R. N. et al. Plasmonic spectrum on 1D and 2D periodic arrays of rod-shape metal nanoparticle pairs with different core patterns for biosensor and solar cell applications. J. Opt. 18, 115003. https://doi.org/10.1088/2040-8978/18/11/115003 (2016).

Lai, C.-H. et al. Near infrared surface-enhanced Raman scattering based on star-shaped gold/silver nanoparticles and hyperbolic metamaterial. Sci. Rep. 7, 5446. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05939-0 (2017).

Lin, C.-T. et al. Rapid fabrication of three-dimensional gold dendritic nanoforests for visible light-enhanced methanol oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 192, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2016.01.043 (2016).

Oscar, Á. -O., Lucas, V. B., Zhiming, W. & Alexander, O. G. Temporal plasmonics: Fano and Rabi regimes in the time domain in metal nanostructures. Nanophotonics 9, 3587–3595. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2020-0229 (2020).

Al-Shammari, R. M. et al. Single-molecule nonresonant wide-field surface-enhanced Raman scattering from ferroelectrically defined au nanoparticle microarrays. ACS Omega 3, 3165–3172. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.7b01285 (2018).

Barnes, E. et al. Photochemically patterned metal nanoparticle strontium barium niobate surfaces with tunable wettability, enhanced Raman scattering, and fluorescence emission. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 011601. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5089746 (2019).

Huang, H. J. et al. Review of experimental setups for plasmonic photocatalytic reactions. Catalysts 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal10010046 (2020).

Li, J. F. et al. Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature 464, 392–395. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08907 (2010).

Liu, X. et al. High sensitivity and homogeneity of surface enhanced Raman scattering on three-dimensional array–film hybrid platform. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 081605. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4977424 (2017).

Si, D. et al. Plasmon-driven surface catalysis on photochemically deposited-based SERS substrates. App. Opt. 55, 8468–8471. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.55.008468 (2016).

Mehmet, K., Emma, R. M., Aysun, K. & Sebastian, W.-H. Fundamentals and applications of SERS-based bioanalytical sensing. Nanophotonics 6, 831–852. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2016-0174 (2017).

Hwang, J. S. et al. The preparation of silver nanoparticle decorated silica nanowires on fused quartz as reusable versatile nanostructured surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates. Nanotechnology 21, 025502. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/21/2/025502 (2010).

Cao, Y. & Sun, M. Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Rev. Phys. 8, 100067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.revip.2022.100067 (2022).

Fang, Y., Zhang, Z. & Sun, M. High vacuum tip-enhanced Raman spectroscope based on a scanning tunneling microscope. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 87, 033104. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4943291 (2016).

Chau, Y.-F., Syu, J.-Y., Chao, C.-T., Chiang, H. P. & Lim, C. Design of crossing metallic metasurface arrays based on high sensitivity of gap enhancement and transmittance-shift for plasmonic sensing applications. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 50, 045105. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6463/aa506b (2017).

Peng, T.-C., Lin, W.-C., Chen, C.-W., Tsai, D. P. & Chiang, H. P. Enhanced sensitivity of surface plasmon resonance phase-interrogation biosensor by using silver nanoparticles. Plasmonics 6, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-010-9165-4 (2011).

Wang, Z. et al. Enhancement of Alq3 fluorescence by nanotextured silver films deposited on porous alumina substrates. App. Phys. Lett. 90, 151119–151119. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2722231 (2007).

Dana, C., Sibyll, P., Carolin, S., Karina, W. & Jürgen, P. SERS-based detection of biomolecules. Nanophotonics 3, 383–411. https://doi.org/10.1515/nanoph-2013-0024 (2014).

Chau, Y.-F.C. et al. Strong and tunable plasmonic field coupling and enhancement generating from the protruded metal nanorods and dielectric cores. Results Phys. 13, 102290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2019.102290 (2019).

Chou Chau, Y.-F. et al. Ultra-high refractive index sensing structure based on a metal-insulator-metal waveguide-coupled T-shape cavity with metal nanorod defects. Nanomaterials 9, 1433. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9101433 (2019).

Hsieh, L.-Z. et al. Metal nano-particles sizing by thermal annealing for the enhancement of surface plasmon effects in thin-film solar cells application. Opt. Commun. 370, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2016.03.009 (2016).

Li, S. et al. Impact of the crystal orientation of Fe-doped lithium niobate on photo-assisted proton exchange and chemical etching. Sci. Rep. 7, 16818. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-16454-7 (2017).

Neumayer, S. M. et al. Thickness, humidity, and polarization dependent ferroelectric switching and conductivity in Mg doped lithium niobate. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 244103. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4938386 (2015).

Sanna, S. & Schmidt, W. G. LiNbO3surfaces from a microscopic perspective. J. Condens. Matter Phys. 29, 413001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-648x/aa818d (2017).

Mu, X. & Sun, M. Interfacial charge transfer exciton enhanced by plasmon in 2D in-plane lateral and van der Waals heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 091601. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0018854 (2020).

Cui, L. et al. In situ plasmon-enhanced CARS and TPEF for Gram staining identification of non-fluorescent bacteria. Spectrochim. Acta 264, 120283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.saa.2021.120283 (2022).

Horák, M. et al. Comparative study of plasmonic antennas fabricated by electron beam and focused ion beam lithography. Sci. Rep. 8, 9640. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28037-1 (2018).

Vieu, C. et al. Electron beam lithography: Resolution limits and applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 164, 111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-4332(00)00352-4 (2000).

Duan, H. et al. Metrology for electron-beam lithography and resist contrast at the sub-10 nm scale. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 28, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1116/1.3501359 (2010).

Joshi-Imre, A. & Bauerdick, S. Direct-write ion beam lithography. J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 170415. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/170415 (2014).

Pavlov, D. V. et al. Multi-purpose nanovoid array plasmonic sensor produced by direct laser patterning. Nanomaterials 9, 1348. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9101348 (2019).

Chau, Y.-F.C. et al. Enhanced photoluminescence of DCJTB with ordered Ag-SiO2 core–shell nanostructures via nanosphere lithography. Results Phys. 17, 103168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rinp.2020.103168 (2020).

Zhang, C., Cvetanovic, S. & Pearce, J. M. Fabricating ordered 2-D nano-structured arrays using nanosphere lithography. MethodsX 4, 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2017.07.001 (2017).

Yoshino, M., Li, Z. & Terano, M. Theoretical and experimental study of metallic dot agglomeration induced by thermal dewetting. J. Micro Nano-Manuf. 3, 021004. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4029685 (2015).

Li, W. & Marconi, M. C. Extreme ultraviolet Talbot interference lithography. Opt. Express 23, 25532–25538. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.025532 (2015).

Pollari, R. & Milstein, J. N. Improved axial trapping with holographic optical tweezers. Opt. Express 23, 28857–28867. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.23.028857 (2015).

Schartner, E. P., Tsiminis, G., Henderson, M. R., Warren-Smith, S. C. & Monro, T. M. Quantification of the fluorescence sensing performance of microstructured optical fibers compared to multi-mode fiber tips. Opt. Express 24, 18541–18550. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.24.018541 (2016).

Chou Chau, Y.-F. et al. Fabrication and characterization of a metallic-dielectric nanorod array by nanosphere lithography for plasmonic sensing application. Nanomaterials 9, 1691. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano9121691 (2019).

Fan, M., Andrade, G. & Brolo, A. A review on the fabrication of substrates for surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy and their applications in analytical chemistry. Anal. Chim. Acta 693, 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2011.03.002 (2011).

Liu, X., Shao, Y., Tang, Y. & Yao, K.-F. Highly uniform and reproducible surface enhanced Raman scattering on air-stable metallic glassy nanowire array. Sci. Rep. 4, 5835. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05835 (2014).

Que, R. et al. Highly reproducible surface-enhanced Raman scattering on a capillarity-assisted gold nanoparticle assembly. Adv. Func. Mater. 21, 3337–3343. https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.201100641 (2011).

Alattar, N. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering for rapid hematopoietic stem cell differentiation analysis. App. Opt. 57, E184–E189. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.57.00E184 (2018).

Carville, N. C. et al. Influence of annealing on the photodeposition of silver on periodically poled lithium niobate. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 054102. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4940968 (2016).

Molina, P. et al. Selective plasmon enhancement of the 1.08 μm Nd3+ laser stark transition by tailoring Ag nanoparticles chains on a PPLN Y-cut. Nano Lett. 13, 4931–4936. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl4028999 (2013).

Neumayer, S. M. et al. Interface and thickness dependent domain switching and stability in Mg doped lithium niobate. J. Appl. Phys. 118, 224101. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4936605 (2015).

Ferraro, P., Grilli, S., Miccio, L. & Vespini, V. Wettability patterning of lithium niobate substrate by modulating pyroelectric effect to form microarray of sessile droplets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 92, 213107. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.2936851 (2008).

Grilli, S. et al. Liquid micro-lens array activated by selective electrowetting on lithium niobate substrates. Opt. Express 16, 8084–8093. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.16.008084 (2008).

Dunn, S. et al. Using the surface spontaneous depolarization field of ferroelectrics to direct the assembly of virus particles. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 3537–3539. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1797535 (2004).

Sun, Y., Eller, B. S. & Nemanich, R. J. Photo-induced Ag deposition on periodically poled lithium niobate: Concentration and intensity dependence. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 084303. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.3647752 (2011).

Carville, N. C. et al. Photoreduction of SERS-active metallic nanostructures on chemically patterned ferroelectric crystals. ACS Nano 6, 7373–7380. https://doi.org/10.1021/nn3025145 (2012).

Wang, T.-J. et al. Electrostatic-field-tunable ferroelectric template for photoreduction of silver nanostructures applied in Raman scattering enhancement. Opt. Mater. Express 7, 2838–2846. https://doi.org/10.1364/OME.7.002838 (2017).

Liu, X. et al. Tunable and highly reproducible surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrates made from large-scale nanoparticle arrays based on periodically poled LiNbO3templates. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 14, 055011. https://doi.org/10.1088/1468-6996/14/5/055011 (2013).

Craig Carville, N., Manzo, M., Denning, D., Gallo, K. & Rodriguez, B. J. Growth mechanism of photoreduced silver nanostructures on periodically proton exchanged lithium niobate: Time and concentration dependence. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 187212. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4801963 (2013).

Hanson, J., Rodriguez, B., Nemanich, R. & Gruverman, A. Fabrication of metallic nanowires on a ferroelectric template via photochemical reaction. Nanotechnology 17, 4946. https://doi.org/10.1088/0957-4484/17/19/028 (2006).

Chen, Y., Cheng, Y. & Sun, M. Physical mechanisms on plasmon-enhanced organic solar cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 125, 21301–21309. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c07020 (2021).

Wang, T. J., Barveen, N. R., Liu, Z. Y., Chen, C. H. & Chou, M. H. Transparent, flexible plasmonic Ag NP/PMMA substrates using chemically patterned ferroelectric crystals for detecting pesticides on curved surfaces. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 13, 34910–34922. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c08233 (2021).

Damm, S. et al. Surface enhanced luminescence and Raman scattering from ferroelectrically defined Ag nanopatterned arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 083105. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4818910 (2013).

Damm, S. et al. Plasmon enhanced Raman from Ag nanopatterns made using periodically poled lithium niobate and periodically proton exchanged template methods. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 26543–26550. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp310248w (2012).

Tseng, M. L., Leu, B.-H., Li, P.-Y., Chung, K. S. & Chiang, H.-P. Multi-color surface plasmon-enhanced photoluminescence of organic dyes using annealed AgOx thin film. Plasmonics 10, 1301–1305. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-015-9930-5 (2015).

Al-Shammari, R. M. et al. Photoinduced enhanced Raman from lithium niobate on insulator template. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 10, 30871–30878. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.8b10076 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Key issues and recent progress of high efficient organic light-emitting diodes. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 17, 69–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jphotochemrev.2013.08.001 (2013).

Liu, T.-H., Iou, C.-Y., Wen, S.-W. & Chen, H. 4-(Dicyanomethylene)-2-t-butyl-6-(1,1,7,7-tetramethyljulolidyl-9-enyl)-4H-pyran doped red emitters in organic light-emitting devices. Thin Solid Films 441, 223–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0040-6090(03)00861-7 (2003).

Liu, X., Osada, M., Kitamura, K., Nagata, T. & Si, D. Ferroelectric-assisted gold nanoparticles array for centimeter-scale highly reproducible SERS substrates. Sci. Rep. 7, 3630. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-03301-y (2017).

Yamada, M., Nada, N., Saitoh, M. & Watanabe, K. First-order quasi-phase matched LiNbO3 waveguide periodically poled by applying an external field for efficient blue second-harmonic generation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 435–436. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.108925 (1993).

Pun, E. Y. B., Kwok Kwong, L. & Po Shuen, C. Proton-exchanged optical waveguides in Z-cut LiNbO/sub 3/ using phosphoric acid. J. Light. Technol. 11, 277–284. https://doi.org/10.1109/50.212539 (1993).

Wang, T.-J., Chang, H.-W., Chen, J.-S. & Chiang, H.-P. Nanotip-assisted photoreduction of silver nanostructures on chemically patterned ferroelectric crystals for surface enhanced Raman scattering. Sci. Rep. 9, 10962. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-47523-8 (2019).

Chau, Y.-F. & Tsai, D. P. Three-dimensional analysis of silver nano-particles doping effects on super resolution near-field structure. Opt. Commun. 269, 389–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.optcom.2006.08.004 (2007).

Chau, Y.-F.C., Chou Chao, C.-T., Lim, C. M., Huang, H. J. & Chiang, H.-P. Depolying tunable metal-shell/dielectric core nanorod arrays as the virtually perfect absorber in the near-infrared regime. ACS Omega 3, 7508–7516. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.8b00362 (2018).

Chou Chau, Y.-F. et al. Tunable optical performances on a periodic array of plasmonic bowtie nanoantennas with hollow cavities. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 11, 411. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-016-1636-x (2016).

Lin, W.-C. et al. SERS study of tetrodotoxin (TTX) by using silver nanoparticles arrays. Plasmonics 4, 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11468-009-9090-6 (2009).

Tseng, M. et al. Multi-level surface enhanced Raman scattering using AgOx thin film. Opt. Express 21, 24460–24467. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.21.024460 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Grooved nanoplate assembly for rapid detection of surface enhanced Raman scattering. Nanoscale 9, 15390–15396. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7NR05228F (2017).

Huang, X., Zhang, H., Xu, D., Wen, F. & Chen, S. Investigation of exciton recombination zone in quantum dot light-emitting diodes using a fluorescent probe. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 27809–27816. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b08574 (2017).

Ayala-Orozco, C. et al. fluorescence enhancement of molecules inside a gold nanomatryoshka. Nano Lett. 14, 2926–2933. https://doi.org/10.1021/nl501027j (2014).

Akselrod, G. M. et al. Probing the mechanisms of large Purcell enhancement in plasmonic nanoantennas. Nat. Photonics 8, 835–840. https://doi.org/10.1038/nphoton.2014.228 (2014).

Huang, H.-L. et al. Surface plasmon-enhanced photoluminescence of DCJTB by using silver nanoparticle arrays. Opt. Express 21, A901–A908. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.21.00A901 (2013).

Xu, Y. et al. Effect of gold nanorods and nanocubes on electroluminescent performances in organic light-emitting diodes and its working mechanism. AIP Adv. 5, 067121. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4922438 (2015).

Wilkerson, C. W., Goodwin, P. M., Ambrose, W. P., Martin, J. C. & Keller, R. A. Detection and lifetime measurement of single molecules in flowing sample streams by laser-induced fluorescence. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62, 2030–2032. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.109495 (1993).

Zyuzin, M. V. et al. Photoluminescence quenching of dye molecules near a resonant silicon nanoparticle. Sci. Rep. 8, 6107. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-24492-y (2018).

Sakurai, T. et al. Time-resolved microphotoluminescence study of Cu(In, Ga)Se2. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 50, 05FC01. https://doi.org/10.1143/jjap.50.05fc01 (2011).

Sung, M.-J., Ma, Y.-F., Chau, Y.-F. & Huang, D.-W. Surface plasmon resonance in a hexagonal nanostructure formed by seven core shell nanocylinders. App. Opt. 49, 920–926. https://doi.org/10.1364/AO.49.000920 (2010).

Johnson, P. B. & Christy, R. W. Optical constants of the noble metals. Phys. Rev. B 6, 4370–4379. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.6.4370 (1972).

Chen, W. T. et al. Electromagnetic energy vortex associated with sub-wavelength plasmonic Taiji marks. Opt. Express 18, 19665–19671. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.18.019665 (2010).

Chau, Y.-F. & Yeh, H.-H. A comparative study of solid-silver and silver-shell nanodimers on surface plasmon resonances. J. Nanopart. Res. 13, 637–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-010-0058-4 (2011).

Chou Chao, C.-T. et al. Highly sensitive and tunable plasmonic sensor based on a nanoring resonator with silver nanorods. Nanomaterials 10, 1399 (2020).

Chou Chau, Y.-F. et al. Perfect dual-band absorber based on plasmonic effect with the cross-hair/nanorod combination. Nanomaterials 10, 493. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano10030493 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (Grant No. MOST 110-2112-M-019-004, MOST 110-2124-M-006-004 and MOST 108-2112-M-006-021-MY3) and University Research Grant of Universiti Brunei Darussalam (Grant No. UBD/RSCH/1.9/FICBF(b)/2022/018). P.C.W. also acknowledges the support from the Ministry of Education (Yushan Young Scholar Program), Taiwan, and in part from the Higher Education Sprout Project of the Ministry of Education (MOE) to the Headquarters of University Advancement at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.F.C.C. investigation, Resources, Conceptualization & Writing, H.E.C., P.S.H., P.C.W., C.M.L., L.M.C., T.J.W., C.T.C.C., investigation, Experiment, Simulation, & data analysis, T.S.K., M.H.S., and H.P.C. conceptualization, Methodology, Review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chau, YF.C., Chang, HE., Huang, PS. et al. Enhanced photoluminescence and shortened lifetime of DCJTB by photoinduced metal deposition on a ferroelectric lithography substrate. Sci Rep 12, 6173 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10303-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10303-y

This article is cited by

-

Optimization of NPD/Alq3/TPBi/Bphen OLED structure and investigation of electrical characteristics along with allied parameters

Optical and Quantum Electronics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.