Abstract

Preventive chemotherapy (PC), the main strategy recommended by the World Health Organization to eliminate soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) and schistosomiasis (SCH), should be strengthened through identification of the remaining SCH transmission foci and evaluating its impact to get a lesson. This study was aimed to assess the prevalence of STH/SCH infections, the intensity of infections, and factors associated with STH infection among school-aged children (SAC) in Uba Debretsehay and Dara Mallo districts (previously not known to be endemic for SCH) in southern Ethiopia, October to December 2019. Structured interview questionnaire was used to collect household data, anthropometric measurements were taken and stool samples collected from 2079 children were diagnosed using the Kato-Katz technique. Generalize mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to assess the association of STH infections with potential predictors. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni in the Dara Mallo district was 34.3% (95%CI 30.9–37.9%). Light, moderate, and heavy S. mansoni infections were 15.2%, 10.9%, and 8.2% respectively. The overall prevalence of any STH infection was 33.2% with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 31.1–35.3%. The intensity of infections was light (20.9%, 11.3% & 5.3%), moderate (1.1%, 0.1% & 0.4%) and heavy (0.3%, 0% & 0%) for hookworm, whipworm and roundworms respectively. The overall moderate-to-heavy intensity of infection among the total diagnosed children was 2% (41/2079). STH infection was higher among male SAC with Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR) of 1.7 (95%CI 1.4–2.1); occupation of the household head other than farmer or housewife (AOR = 0.5; 95%CI 0.3–0.8), middle [AOR = 1.1; 95%CI 1.0–1.3] or high [AOR = 0.7; 95%CI 0.5–0.9] socioeconomic status. Dara Mallo district was moderate endemic for S. mansoni; and it needs sub-district level mapping and initiating a deworming campaign. Both districts remained moderate endemic for STH. Evidence-based strategies supplementing existing interventions with the main focus of the identified factors is important to realize the set targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Schistosomiasis (SCH) and soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) are the two most common Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) affecting economically deprived people living in warm and moist tropical areas1. SCH is caused by blood flukes of the genus Schistosoma. Humans become infected by these flukes when the larval form of the parasite, released into the water by the freshwater snail host, penetrates the skin during contact with infested water. It was reported from 78 countries, but 90% of moderate-to-heavy infections requiring preventive chemotherapy (PC) live in Africa. There are two major forms of SCH (intestinal and urogenital) with the intestinal form caused by S. mansoni being the most common in Ethiopia2.

STH is caused by helminths of the roundworms (Ascaris lumbricoides), the whipworms (Trichuris trichiura), and the hookworms (Ancylostoma duodenal or Necator americanus). Humans are infected by these helminths through ingestion of food or water contaminated with embryonated eggs of roundworms and whipworms or active penetration of the skin by filariform (infective 3rd stage) larvae of hookworms from infested soil1. The World Health Organization (WHO) update on March 2020 indicated that about 1.5 billion or 24% of the world population was infected by STHs3.

The morbidities associated with SCH were due to the reaction of the body to the eggs lodged in the blood vessels. Intestinal SCH can result in abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloody stool. In the advanced stage of the disease, there is an enlargement of the spleen and liver, which is associated with accumulation of the fluid in the peritoneal cavity and hypertension of abdominal blood vessels. In children, SCH causes anemia, stunting, and reduced ability to learn. In some chronic cases, SCH can lead to death. The WHO estimated that the annual death rate due to SCH was 200,000 globally2. The symptoms of STH depend on the intensity of infection and are attributable to their chronic nature and insidious impact on the health and quality of life than mortality. In moderate-to-heavily infected individuals, STH impairs the physical growth, cognitive development, and micronutrient deficiencies leading to poor school performance and absenteeism in SAC; reduced work productivity and adverse pregnancy outcomes in adults4.

In Ethiopia, about 79 million people, including 25.3 million SAC were living in STH endemic areas while the corresponding numbers for intestinal SCH were 37.3 million and 12.3 million in 20135. The 2013 and 2015 national SCH and STH mapping carried out in Ethiopia revealed that the overall prevalence of STH and SCH infections was 21.7% and 3.5% respectively6. Ethiopia launched the national NTD control program in November 2015 and targeted to eliminate morbidity due to STH and SCH among SAC by 2020 and break transmission by 2025. In its 1st national PC campaign, Ethiopia achieved 100% geographic coverage and the individual treatment coverage was 77% and 76.5% for SCH and STH respectively5,7. However, the coverage validation survey undertaken in March 2019, indicated that the treatment coverage varied widely per district ranging from 54.4% to 91.6% for STH and 59.7% to 89.6% for SCH8,9.

To overcome the morbidities from STH and SCH, the WHO recommends chemoprevention as a public health intervention to reduce the worm burden for preschool children, SAC, adolescent girls, women of the reproductive age group, and adults in certain high-risk occupations1. Though PC and other supplementary interventions reduced the prevalence and intensity of STH infections, the gain was spatiotemporally heterogeneous, suggesting stringent monitoring and evaluation of the deworming process to be undertaken in different contexts10.

SCH and STH morbidity elimination and transmission breaking targets need consistent monitoring and evaluation of the interventions to get lessons and customize the existing interventions. However, the SCH transmission foci are not exhaustively identified, the impact of the existing interventions on the distribution of STH and SCH were poorly addressed in hard-to-reach areas like Dara Mallo and Uba Debretsehay districts. Therefore, the present study was primarily aimed to estimate the prevalence of STH and SCH infections, the intensity of the infections after 5 years PC against STH among SAC. In addition, factors affecting STH infections were assessed in Dara Mallo and Uba Debretsehay districts. This study was embedded in baseline data collected for a cluster-randomized trial that is used to assess the effect of malaria prevention education on malaria, anemia, and cognitive performance of SAC in the study area. The trail was registered in PACTR with Trail registration identification of PACTR202001837195738 on 21 January 2020. The findings of this cross-sectional study will be used by decision-makers to customize the existing interventions or look for supplementary interventions to accelerate reaching the set targets of morbidity elimination and transmission break of STH and SCH.

Methods

Study setting

This study was conducted in Dara Mallo and Uba Debretsehay districts in Gamo and Gofa Zones respectively. Both zones are found in Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Regional (SNNPR) state which is the 3rd populous region among the 9 regional states in Ethiopia. Both districts are located in the western part of Arba Minch town, capital of the former Gamo Goffa zone, as indicated in Fig. 1. Based on the 2007 national census, a total of 150,145 people were living in the two districts and of whom 76,550 (51%) were male11. According to the recent update of the population by the respective districts, there were a total of 94,396 people in the Uba Debretsehay district and 110,207 people in the Dara Mallo district. All 32 schools (20 from Uba Debretsehay and 12 from Dara Mallo) involved in the study are located in an altitude range below 2000 MASL.

Study design and sample size

A cross-sectional study was undertaken by recruiting children aged 5–14 years, attending their education in grades 1, 2, and 3 in the 32 primary schools in the study area. The sample size to address the primary objective of this study was computed by using single population proportion formula by assuming that 50% of the children were infected by either STHs or intestinal schistosomiasis (P); 5% margin of error (d) and design effect of 3.0

After adding the 10% non-response rate, the estimated sample size was 1268. However, this study was embedded in a large cluster-randomized trial conducted to evaluate the effect of malaria prevention education on malaria, anemia, and cognitive development among SAC in the study area. The estimated sample size of the trial was 2304. Since increasing sample size reduces the sampling error and increases the power of the study, we have included all children who consented, participated in the interview, and gave stool specimens for the laboratory diagnosis.

Sampling techniques and method of data collection

Seventy-two children from each school were selected using a systematic random sampling technique with a class roster as the sampling frame. The number of participants from each grade level (grade 1 to 3) was determined by the relative contribution of students to the total enrolment in each school. Children who were aged between 5 and 14 years and attending their education in the schools during the data collection period were included in the study while those mentally not fit to respond to questions directed to them, with physical problems to measure their height were excluded from the study. Children enrolled in the study were used to trace their households. Participants' households were approached by trained data collectors for interview and observation. A pretested and structured questionnaire, uploaded to the android version Open Data Kit (ODK) application, was used to collect data through face-to-face interviews with mothers/caretakers of the selected children on socio-demographic characteristics, socioeconomic factors, and water access. It was also used to observe the type of sanitation facilities and their cleanliness and a face-to-face interview with the selected SAC on hygienic practice. The coordinates of household location were taken using GPS (Global Positioning System). The data collectors were trained on how to use the ODK for data collection and ethical procedures.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements were taken according to the WHO guideline12. Children were weighed by using Seca digital scales. The scales were placed on a hard and flat surface. Children were weighed with their lightweight clothing (excluding shoes, belts, socks, watches, and jackets). Each child's weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg by two individuals. If the two measurements differ by more than 0.1 kg a third measurement was made and the two closest measurements with a difference less than or equal to 0.1 kg were recorded.

When measuring the height of a child, he or she stood with his/her back against the board, his/her heels, buttocks, shoulders, and head touching a flat upright sliding headpiece. The child's legs were placed together with the knees and ankles brought together. Children were asked to take in a deep breath. The child's height measurement was taken when the child had maximum inspiration. The headpiece was brought down onto the uppermost point on the head and the height was recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm at the examiner's eye level. In this case, also, the height was measured by two data collectors, and a difference of 0.5 cm was tolerated. In cases when the difference between the two measurements was greater than 0.5 cm, a third measurement was taken and the nearest two measurements were recorded like the measurement done for weight.

Stool examination

After instructing children on how to collect stool specimens without contamination with soil, urine or any dirty material, a polyethylene screw cupped stool container was given to selected students to bring the stool specimen. The collected stool specimen was transported to Wacha and Beto health centers for laboratory diagnosis within the same day of its collection. Single stool smear was prepared following the manufacturer's instruction of the Kato-Katz thick smear technique. The prepared stool is left for 30 min after preparation and examined under a bright-field microscope within an hour of smear preparation. The template used for the preparation of the smear was 41.7 mg13. The number of helminth eggs present in the whole smear was counted and written in laboratory report form designed for this purpose14.

Data analysis

The number of egg counts in the whole preparation of Kato-Katz thick smear and data collected using android version ODK application was converted to comma-separated values (CSV) file. Multiple factor analysis by using household assets, housing conditions, source of drinking water, agricultural land area, and the number of domestic animals was used to generate the wealth index of a household to measure socioeconomic status. The 1st dimension was categorized into tertiles to classify the household economic status into poor, middle, and high. These data were subjected to descriptive statistical analysis like the proportion for categorical variables and plots and descriptive measures for continuous data.

The total number of ova counted from the whole preparation of the Kato-Katz thick smear was multiplied by 24 to get the number of ova per gram of stool specimen. This count was used for further classification of the infections into light, moderate and heavy infections. The prevalence of STH infection in each school involved in the study was computed to determine the endemicity of the infection: low, moderate, or high endemic13.

The GPS coordinates taken from each household point were used to calculate the average point to represent the geographic location of the respective schools. Geospatial distribution of endemicity of the infections per school was presented by using quantum geographic information system (QGIS) version 3.12.1. This software is used to create map of the study area and the endemicity of STH and S. mansoni infection per schools studied15.

Univariable and multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression models were used to assess the association between STH infections with the potential predictor variables by taking schools as a random variable. Selection of variables for multivariable mixed-effect logistic regression was made through stepwise backward variable selection method in which variable with the largest P-value is removed from the model and checked for AIC. If removal of a variable from the model improves the AIC value, it is removed from the model, otherwise, it is maintained in the model. In all cases, P-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The trial to which this study was imbedded was approved by the written consent procedure to be followed by the Institutional Research Ethics Review Board (IRB) in College of Medicine and Health Sciences at Arba Minch University with the reference number of IRB/154/12. The trial was conducted according to the Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomized trials16. It is registered in the Pan African Clinical Trials Registry with a trial ID of PACTR202001837195738. Official request of the permission letter to conduct the research was submitted to district health offices and education offices in Dara Mallo and Uba Debretsehay districts. Support letter written by the respective education offices to support and participate in the study was given to each of the selected schools. The school headmasters were given a support letter from the education offices and written consent was obtained. Parents of the selected SAC were requested to come to the schools and written informed consent was obtained before data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from each of the selected student's parents at the school and documented in the college of medicine and Health Sciences in Arba Minch University. Children positive in stool examination were treated by using a single dose of 400 mg Albendazole for STH and 40 mg of Praziquantel /kg in two divided doses for S. mansoni.

Results

A total of 2304 SAC were approached to participate in the study, but complete data were obtained from 2079 participants (1362 from Uba Debretsehay district), giving a response rate of 90.2%. Of the total participated children, almost half (1040/2079) were male and the mean age of SAC was 8.7 years with a standard deviation (SD) of 1.5 years. The detailed socio-demographic characteristics of participants were indicated in Table 1.

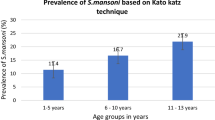

Prevalence, intensity and endemicity of infections

Overall, the prevalence of intestinal helminth infection was 44.6% (95%CI 42.5–46.8%) and infection only by STH was 33.2% (95%CI 31.1–35.3%). The prevalence of S. mansoni among SAC in the Dara Mallo district was 34.3% (246/717) with 95%CI of 30.9–37.9%. The prevalence of each species of parasite, intensity of the infection and the median (IQR) of the egg count among infected children was presented in Table 2.

The prevalence of STH infection varied widely per school. Of the total 32 schools involved in this study, in 10, 13, and 9 of the schools, the prevalence was low, moderate, and high endemic respectively. Half of the schools (n = 6/12) involved in the study from the Dara Mallow district were high endemic for STH. The geospatial distribution of low, moderate, and high prevalence of infections per school in each district was depicted (Fig. 2).

The prevalence of S. mansoni infection also varied widely per school with the minimum prevalence observed was in Shella Subo primary school (3.2%) and the highest prevalence was in Hoya school (90.8%). Concerning the endemicity of infections per school involved in the study, only 3 out of 12 schools were low-endemic, 5 were moderate-endemic and 4 were high-endemic. The geospatial distribution of S. mansoni endemicity per school in the Dara Mallo district was shown in Fig. 3.

Predictors of STH infection

After fitting the model in multivariable mixed-effects logistic regression, factors significantly influencing STH infections were district of the residence, gender of the SAC, occupational status of the household head, and wealth index of the household. Being resident in Dara Mallo district [AOR = 3.2; 95%CI 1.9–5.2]; male gender [AOR = 1.7; 95%CI 1.4–2.1], occupational status of the household head other than farmer/housewife [AOR = 0.5; 95%CI 0.3–0.8] and middle [AOR = 1.1; 95%CI 1.0–1.3] or high [AOR = 0.7; 95%CI 0.5–0.9] socioeconomic status (Table 3). Most of water access, sanitation, and hygiene-related factors significantly influenced STH infection in univariable mixed-effect logistic regression but they did not significantly predict STH infection by SAC in multivariable mixed-effect logistic regression (Table 4).

Discussion

The prevalence of STH infection, infection by S. mansoni, their intensity of infection, and infections associated risk factors among SAC after 5 years of MDA against STH in Dara Mallo and Uba Debretsehay districts were assessed in the present study. The prevalence of any STH infection was 33.3% and the overall prevalence of moderate-to-heavy STH infection among all children was 2.0%. The prevalence of S. mansoni infection and its heavy intensity of infection were 34.3% and 24.0% respectively. Infection by any STH among SAC in the study area was affected by the gender of the child, occupational status of the household head, and economic status, but none of the sanitation and hygiene-related factors influenced STH infection significantly.

The prevalence of any STH infection in Uba Debretsehay and Dara Mallo districts remain moderate endemic at the end of 2019 indicating achieving elimination of morbidity target which is defined as the prevalence of moderate-to-heavy for STH and heavy infections for S. mansoni < 1% among SAC14 and needs a continuation of the morbidity elimination strategies. The prevalence of STH infection in this study was in agreement with Chuahit district17 in Northern Ethiopia while it was higher than findings of similar studies undertaken in Jima town18 and Gurage Zone19 in Ethiopia. In contrast to this, the prevalence of STH infection among SAC in the study area was lower than that found in Hawassa town20 and west Shewa Zone21 in Ethiopia. The disagreements in the prevalence of STH infections in these studies could be related to the time of the data collection relative to the year when deworming has started, since deworming could reduce the worm burden and transmission. The high prevalence of STH infection in this study area as compared to other studies mentioned above might be related to the high prevalence of STH infection before deworming program was started in Ethiopia or the difference in the adherence of STH prevention measures. Except in Kenya22,23, the prevalence of STH infection was higher in the current study area than in other areas outside Ethiopia. It was higher than the prevalence of STH infection in Cameroon24,25 and Sudan26. The high prevalence observed in Kenya as compared to the current study might be due to differences in the data collection time relative to the last deworming or the frequency of deworming undertaken as a method used to eliminate STH infection associated morbidities. One of the two studies mentioned from Cameroon was undertaken 2 months post-MDA unlike the present study24.

Different factors influenced infection of STH in Uba Debretsehay and Dara Mallo districts. One of the socio-demographic factors that influenced STH infection by children was being male. Male children might be more engaged in playing with infested soil outside the houses than females that support their mother and other girls who were more concentrated in activities within the house compounds23. This was in agreement with findings from Gurage Zone19 and T.trichuira infection in Cameroon25. The other identified factor influencing STH infection was the economic level of the household. It is known that STH and other neglected tropical diseases were more common in economically disadvantaged populations. This was corroborated in the present study as those in middle or high economic status were at decreased risk of infection as compared to those in the lower economic category1. A community-based study carried out in northern Ethiopia also demonstrated that children from households with poor wealth Index were more likely to be infected by intestinal parasites27.

Poor access to improved water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practice were one of the areas for intervention to eliminate STH and SCH. However, improved water source, hand washing after the last recent toilet and before last recent meals by child did not affect STH infection. One large-scale cluster-randomized trial was carried out to assess whether provision of water supply, hand washing facility, sanitation facility, drinking water, and provision of behavioral change education and promotion from 2014 to 2017 in Laos did not influence STH infection28. Similar to this study, a survey undertaken in Gurage Zone19 and in Jawi town29 revealed that STH infection was not affected by trimming nails. Another similar study undertaken in West Shewa Zone indicated that untrimmed nail and availability of latrine at household level did not associate with STH infection21. In contrast to the present study, other studies carried out in Ethiopia17,29,30 and abroad22,23 found a significant influence of WASH related factors on STH infections. The disagreement of these might be linked to social desirability bias as over-reporting of positive hygienic behavior than the real practice of the study participants31 and might be difference in the level of improved water access, sanitation and hygiene that can interrupt the transmission of the parasites.

The prevalence of S. mansoni in the Dara Mallo district was moderate-endemic though it was not targeted in the national MDA campaign for the last 5 years. This might be occurred due to a sampling problem during mapping as the sample collected from five schools32 would not show the full picture of the district. The transmission of S. mansoni was more focal and observed in schools that are in the Wacha cluster of the studied schools. This cluster involves schools in the town and those surrounding it. There were irrigation canals almost surrounding the town and which might be the major source for breading the snail hosts important to complete the life cycle of S. mansoni. The prevalence of S. mansoni infection in the present study was higher than other studies conducted in Ethiopia such as Jima town33, Manna34 and Chuahit17 district in northern Ethiopia, Sabatamit (rural Bahir dar)35 in Northern Ethiopia, in west Shewa Zone21 and Wondo district in west Arsi Zone36. The high prevalence of infection and intensity of infections were due to the absence of periodic MDA to reduce the transmission and morbidity of the infection in the present study area. S. mansoni infection was lower than the prevalence of its infection in Ljinga Island in Tanzania37 which could be related to the difference in the frequency of contact of children with the water bodies that inhabit S. mansoni infected snails. Children who had habit of swimming on water bodies were at higher risk of infection. In the majority of the studies, infection by SCH was positively affected by children who had the habit of swimming on water bodies: Chuahit17, Sabatamit rural Bahir Dar35, west Shewa zone21 and Korhogo in Côte d’Ivoire38.

There were limitations related to this study. One of these is due to the type of study design used. The cross-sectional study design, used in this study, is poor in generating evidence on the causal relationship. The strength of this study was using a large sample size to generate evidence on the infection status of children on STH and SCH and reaching children in remote and hard-to-reach areas.

Conclusion

The prevalence of STH infection remained moderate in both districts with the highest prevalence observed in the Dara Mallo district. This implies that achieving the morbidity elimination target by 2020 is not achievable. Thus, stringent monitoring of the deworming process and coverage validation survey should be undertaken to improve the implementation of the interventions and accelerate the elimination of these diseases as a public health problem. More attention should be given to male children, children from low socioeconomic status and improving the level of access to improved water, sanitation and hygiene than the its mere presence. The clustered nature of S. mansoni infection in the Dara Mallo district pinpoints the importance of sub-district level mapping and initiating PC based on the mapping result. Furthermore, studies focusing on the transmission dynamics and interventions targeting the snail host shall be considered.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study will be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AIC:

-

Akaike Information Criterion

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COR:

-

Crude odds ratio

- GPS:

-

Global Positioning System

- IRB:

-

Institutional Research Ethics Review Board

- MDA:

-

Mass Drug Administration

- ODK:

-

Open Data Kit

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PC:

-

Preventive chemotherapy

- QGIS:

-

Quantum Geographical Information System

- SAC:

-

School-aged children

- SCH:

-

Schistosomiasis

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SNNPR:

-

South Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

- STH:

-

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

WHO. Guideline: Preventive Chemotherapy to Control Soil-Transmitted Helminth Infections in At-Risk Population Groups (World Health Organization, 2017).

WHO. Schistosomiasis (2020). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/schistosomiasis. (Accessed 2 Mar 2020).

WHO. Soil-transmitted helminth infections: (WHO, 2020). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/soil-transmitted-helminth-infections. (Accessed 2 Mar 2020).

WHO. Soil-transmitted helminthiases: eliminating soil-transmitted helminthiases as a public health problem in children: progress report 2001–2010 and strategic plan 2011–2020. (2012).

Negussu, N. et al. Ethiopia schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthes control programme: Progress and prospects. Ethiop. Med. J. 55(Suppl 1), 75–80 (2017).

Leta, G. T. et al. National mapping of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Ethiopia. Parasit. Vectors 13(1), 437 (2020).

Health FDRoEMo. Ethiopian schistosomiasis and soiltransmitted helminthiasis National Control Programme Year 2 Plan (2016–2017) (Health FDRoEMo, 2016).

Asfaw, M. A. et al. Preventive chemotherapy coverage against soil-transmitted helminth infection among school age children: Implications from coverage validation survey in Ethiopia, 2019. PLoS ONE 15(6), e0235281 (2020).

Chisha, Y. et al. Praziquantel treatment coverage among school age children against Schistosomiasis and associated factors in Ethiopia: A cross-sectional survey, 2019. BMC Infect. Dis. 20(1), 872 (2020).

Assoum, M. et al. Spatiotemporal distribution and population at risk of soil-transmitted helminth infections following an eight-year school-based deworming programme in Burundi, 2007–2014. Parasit. Vectors 10(1), 583 (2017).

Ministry of Health. National Malaria Guidelines. 3rd ed. Addis Ababa: Federal Ministry of Health of Ethiopia. (2012). https://www.medbox.org/nationalmalaria-guidelines-ethiopia/download.pdf. (Accessed 21 May 2019).

WHO. Training Course on Child Growth Assessment, 2008 (World Health Organization, 2009).

WHO. Assessing the efficacy of anthelminthic drugs against schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiases (2013).

WHO. Soil-transmitted Helminthiasis—Eliminating Soil-transmitted Helminthiases as a Public Health Problem in Children. Soil-transmittted Helminthiases Progress Report 2001–2010 and Strategic Plan 2011–2020 (World Health Organization, 2012).

Team QD. QGIS Geographic Information System version 3.12.1. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project (2020) http://qgis.osgeo.org.

Campbell, M. K., Piaggio, G., Elbourne, D. R. & Consort, A. D. G. Consort 2010 statement: Extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012, 345 (2012).

Alemu, A., Tegegne, Y., Damte, D. & Melku, M. Schistosoma mansoni and soil-transmitted helminths among preschool-aged children in Chuahit, Dembia district, Northwest Ethiopia: Prevalence, intensity of infection and associated risk factors. BMC Public Health 16, 422 (2016).

Mekonnen, Z., Getachew, M., Bogers, J., Vercruysse, J. & Levecke, B. Assessment of seasonality in soil-transmitted helminth infections across 14 schools in Jimma Town, Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. 32, 6 (2019).

Weldesenbet, H., Worku, A. & Shumbej, T. Prevalence, infection intensity and associated factors of soil transmitted helminths among primary school children in Gurage zone, South Central Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study design. BMC. Res. Notes 12(1), 231 (2019).

Eyamo, T., Girma, M., Alemayehu, T. & Bedewi, Z. Soil-transmitted helminths and other intestinal parasites among schoolchildren in southern Ethiopia. Res. Rep. Trop. Med. 10, 137–143 (2019).

Ibrahim, T. et al. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminths and Schistosoma mansoni: A base-line survey among school children, Ejaji, Ethiopia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 12(12), 1134–1141 (2018).

Worrell, C. M. et al. A cross-sectional study of water, sanitation, and hygiene-related risk factors for soil-transmitted helminth infection in urban school- and preschool-aged children in Kibera, Nairobi. PLoS ONE 11(3), e0150744 (2016).

Pasaribu, A. P., Alam, A., Sembiring, K., Pasaribu, S. & Setiabudi, D. Prevalence and risk factors of soil-transmitted helminthiasis among school children living in an agricultural area of North Sumatera, Indonesia. BMC Public Health 19(1), 1066 (2019).

Tabi, E. S. B., Eyong, E. M., Akum, E. A., Löve, J. & Cumber, S. N. Soil-transmitted Helminth infection in the Tiko Health District, South West Region of Cameroon: A post-intervention survey on prevalence and intensity of infection among primary school children. Pan Afr. Med. J. 30, 74 (2018).

Nkengni, S. M. M. et al. Current decline in schistosome and soil-transmitted helminth infections among school children at Loum, Littoral region, Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med. J. 33, 94 (2019).

Cha, S. et al. Epidemiological findings and policy implications from the nationwide schistosomiasis and intestinal helminthiasis survey in Sudan. Parasit. Vectors 12(1), 429 (2019).

Gizaw, Z., Addisu, A. & Gebrehiwot, M. Socioeconomic predictors of intestinal parasitic infections among under-five children in rural Dembiya, Northwest Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. Environ. Health Insights. 13, 1178630219896804 (2019).

Chard, A. N., Garn, J. V., Chang, H. H., Clasen, T. & Freeman, M. C. Impact of a school-based water, sanitation, and hygiene intervention on school absence, diarrhea, respiratory infection, and soil-transmitted helminths: Results from the WASH HELPS cluster-randomized trial. J. Glob. Health. 9(2), 020402 (2019).

Sitotaw, B., Mekuriaw, H. & Damtie, D. Prevalence of intestinal parasitic infections and associated risk factors among Jawi primary school children, Jawi town, north-west Ethiopia. BMC Infect. Dis. 19(1), 341 (2019).

Teshale, T., Belay, S., Tadesse, D., Awala, A. & Teklay, G. Prevalence of intestinal helminths and associated factors among school children of Medebay Zana wereda; North Western Tigray, Ethiopia 2017. BMC. Res. Notes 11(1), 444 (2018).

Aiemjoy, K. et al. Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminth and intestinal protozoan infections in preschool-aged children in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 96(4), 866–872 (2017).

Leta, G. et al. National mapping of soil-transmitted helminth and schistosome infections in Ethiopia. (2020).

Tefera, A., Belay, T. & Bajiro, M. Epidemiology of Schistosoma mansoni infection and associated risk factors among school children attending primary schools nearby rivers in Jimma town, an urban setting, Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE 15(2), e0228007 (2020).

Bajiro, M. et al. Prevalence of Schistosoma mansoni infection and the therapeutic efficacy of praziquantel among school children in Manna District, Jimma Zone, southwest Ethiopia. Parasit. Vectors 9(1), 560 (2016).

Workineh, L., Yimer, M., Gelaye, W. & Muleta, D. The magnitude of Schistosoma mansoni and its associated risk factors among Sebatamit primary school children, rural Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC. Res. Notes 12(1), 447 (2019).

Ansha, M. G., Kuti, K. A. & Girma, E. Prevalence of intestinal schistosomiasis and associated factors among school children in Wondo District, Ethiopia. J. Trop. Med. 2020, 9813743 (2020).

Mueller, A., Fuss, A., Ziegler, U., Kaatano, G. M. & Mazigo, H. D. Intestinal schistosomiasis of Ijinga Island, north-western Tanzania: Prevalence, intensity of infection, hepatosplenic morbidities and their associated factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 19(1), 832 (2019).

M’Bra, R. K. et al. Risk factors for schistosomiasis in an urban area in northern Côte d’Ivoire. Infect. Dis. Poverty 7(1), 47 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Arba Minch University for funding the research budget for data collection, the London Centre for Neglected Tropical Disease Research for the kind support of Kato-Katz kits, Dara Mallo, and Uba Debretsehay district health offices for informing lists of kebeles. Our sincere appreciation also goes to the education offices of both districts and school directors who facilitated the data collection process, those involved in the data collection, and parents for devoting their time to come to school to provide assent and interview.

Funding

Arba Minch University financed the data collection process. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Z., J-P.V.G., H.B., S.A. and F.M. conceived the idea, designed the study, analyzed, interpreted and drafted the manuscript; M.M., M.S. and Y.C. conceived and involved in acquisition of the data; G.B., A.T. and T.Y. conceived the idea.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zerdo, Z., Bastiaens, H., Anthierens, S. et al. Prevalence, intensity and endemicity of intestinal schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis and its associated factors among school-aged children in Southern Ethiopia. Sci Rep 12, 4586 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08333-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-08333-7

This article is cited by

-

Epidemiology of soil-transmitted helminth infections and the differential effect of treatment on the distribution of helminth species in rural areas of Gabon

Tropical Medicine and Health (2024)

-

Fine mapping of Ascaris lumbricoides, Trichuris trichiura and hookworm infections in sub-districts of Makenene in Centre Region of Cameroun

Scientific Reports (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.