Abstract

We aimed to investigate if declines in youth’s mental health during lockdown were dependent on housing condition among 7445 youth (median age ~ 20 years) from the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC), with data collected at 18 years of age and again three weeks into the first national lockdown (April 2020). We examined associations between housing conditions (access to outdoor spaces, urbanicity, household density, and household composition) and changes in mental health (mental well-being, Quality of Life (QoL) and loneliness). We report results from multivariate linear and logistic regression models. Youth without access to outdoor spaces experienced greater declines in mental well-being (vs. garden; mean difference: − 0·75 (95% CI − 1·14, − 0·36)), and correspondingly greater odds of onset of low mental well-being (vs. garden; OR: 1·72 (95% CI 1·20, 2·48)). Youth in higher density households vs. below median or living alone vs. with parents only also had greater odds of onset of low mental well-being (OR: 1·26 (95% CI 1·08, 1·46) and OR: 1·62 (95% CI 1·17, 2·23), respectively). Living in denser households (vs. below median; OR: 1·18 (95% CI 1·06, 1·33), as well as living alone (vs. with parents; OR: 1·38 (95% CI 1·04, 1·82) was associated with onset of low QoL. Living alone more than doubled odds of onset of loneliness compared to living with parents, OR: 2·12 (95% CI 1·59, 2·82). Youth living alone, in denser households, and without direct access to outdoor spaces may be especially vulnerable to mental health declines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Differences in housing conditions may become increasingly apparent when a large portion of the population is mandated or recommended to spend the majority of their time at home, as has been the case under in nationwide lockdowns implemented globally to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought with it public health and political actions varying across countries in their degrees of restrictions1, but all scenarios likely resulted in increased time spent in individuals' residency. Additional lockdowns have occurred in some nations and despite vaccine availability are still being implemented, where restrictive measures are chosen to curb national and regional spread. In Denmark, the national lockdown in spring 2020 was announced March 11th and effective from March 13th, 20201. It involved closing of the national boarders, restaurants/bars, sports facilities, schools and public workplaces, and recommendations to social distance and engage in only essential activities2.

Previous studies have documented changes in mental health from before to during initial national lockdowns3,4,5,6, highlighting how youth have been disproportionately affected3,7,8. A few studies have described cross-sectional associations between housing conditions and mental health during initial lockdowns9,10,11, as well as before and after measures of loneliness in separate samples12. To our knowledge, no previous studies have documented changes in young people’s mental health from before to during a lockdown in relation to the housing conditions one must ‘stay home’ in. Using prospectively-collected mental health data, we examined whether mental health declines among Danish youth were dependent on their housing conditions during the initial national COVID-19 lockdown.

Materials and methods

Population

The Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) consists of mothers and offspring from approximately 100 000 pregnancies enrolled in the cohort during the years 1996 to 200213. The pregnant women responded to computer assisted telephone interviews twice during pregnancy and twice in the child’s two first years of life. Additional follow-ups were conducted at offspring ages 7, 11, and more recently, 18 years. In the 18-year follow up, invitations were sent three months after participants’ 18th birthday. This data collection was initiated in March 2016 and will be completed ultimo 2021; detailed information on DNBC is available at: www.dnbc.dk. Most recently, in the 3rd week of the national Danish COVID-19-related lockdown, mothers and their offspring for whom we had either a private e-mail address or phone number were invited to participate in a COVID-19 online questionnaire, and all participants who responded within a week were re-invited to up to six subsequent consecutive online questionnaires2. In this study, we used data on offspring’s mental health from the 18-year follow-up (baseline) as a before lockdown measure and data on housing conditions and mental health from the first of the COVID-19 online questionnaires (follow-up) as a during lockdown measure, eFigure 1.

Mental health outcomes

We examined changes in mental health with the following three parameters:

-

1)

Mental well-being

Changes in mental well-being were measured as the difference in metric scores on the 7-item Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (SWEMWBS)14,15,16. This instrument has been validated in a Danish sample, including participants in the age range we studied15. The scale ranges from 7 to 35, with higher values indicating better well-being. Because a score of ≤ 20 corresponds to possible or probable anxiety or depression16, we used this cut-off to define low vs. normal mental wellbeing.

-

2)

Quality of life (QoL)

Changes in quality of life (QoL) were reported on an adaptation of the Cantril Ladder scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represented the ‘worst possible life’ and 10 ‘the best possible life’17. In addition to treating the outcome as a continuous variable, we also categorized participants with a score of 5 or lower as having a low QoL and above 5 as normal QoL, in line with previous research17,18.

-

3)

Loneliness

Changes in loneliness were measured only as a binary outcome. Loneliness was measured with similar Likert scales at baseline and follow-up. At baseline, participants were asked ‘How often do you feel lonely?’ with response options: ‘Never’, ‘Occasionally’, ‘Often’, ‘Very often’ or ‘Unsure’ (excluded). ‘Often’ and ‘Very often’ responses were categorized as lonely vs. not lonely. At follow-up, participants were asked ‘In the last week, how often have you felt lonely?’ with the following response options: ‘Seldom or not at all (less than 1 day)’, ‘Some or a little (1–2 days)’, ‘Occasionally or often (3–4 days)’ or ‘Most of the time (5–7 days)’. Responses with a minimum of three days were categorized as lonely vs. not lonely.

Housing conditions during lockdown

We examined the following four housing conditions:

-

1)

Direct access to outdoor spaces

Direct access to outdoor spaces was defined as not having direct access to outdoor spaces or having direct access to a common yard only, a balcony only, a garden only, or multiple outdoor spaces/other (e.g. a garden and a balcony). For descriptive analyses only, the variable was dichotomized into no or direct access to any of the aforementioned outdoor spaces.

-

2)

Urbanicity

Urbanicity was defined as residential degree of urbanicity, defined by the European Union, using the following municipality-level population density categorizations: rural (thinly populated), semi-urban (intermediate density) and urban (densely populated)19. Postal codes for residency at follow-up were self-reported.

-

3)

Household density

Household density was defined as the reciprocal of average square meters per person in the household, i.e. 1/( square meters/number of person in household). The housing area was reported in 10 square meters intervals, e.g. 50 to 59, and we therefore used the middle value. Children and adults were counted similarly, rather than assigning lower value for children. The distribution was split at the median value to create a binary variable for both the descriptive and regression analyses. The continuous variable was used in models where household density was a covariate.

-

4)

Household composition

Household composition was categorized as living alone, with friends or roommates (including in a dormitory), with a partner, with parents only, or with parents and children or siblings. For descriptive analyses, the variable was dichotomized into living without parents (i.e. alone, with a friend/roommate, and partner) or living with parents (i.e. living with parents only and living with parents and siblings/children).

Covariates

Data on sex (male, female), current educational enrolment (not a student, ISCED 0–2, ISCED 3–4, ISCED 5–8, and ‘other education’), part-time work (yes, no), moving during lockdown (moved from residency/other postal code: yes, no) and geographical region (Capital City Region, Region Zealand, Region of Southern Denmark, Mid Jutland Region, North Jutland Region) were considered potential covariates.

Three variables were considered a priori for interaction analyses: sex, quarantine and self-reported psychiatric illnesses. Quarantine was defined as those who at follow-up reported having been in quarantine or isolation during the last 14 days. Psychiatric illnesses were self-reported and respondents could choose between the following answers: ‘no history of psychiatric illness’, ‘current psychiatric illnesses’, ‘previous psychiatric illnesses’, or ‘unsure’. Youth reporting current psychiatric illness and those who were ‘unsure’ were grouped together (since respondents who were ‘unsure’ resembled those with a current psychiatric illness most in terms of mental health measures), and those with previous illnesses or none were grouped together.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in Stata 15.0 (StataCorp, Tx, USA).

Absolute and relative frequencies are presented for the dichotomized exposure variables and median and interquartile ranges are presented for continuous covariates. Unadjusted mean changes in mental well-being (SWEMWBS) scores were computed for each category in each exposure. Kernel density plots and bar plots were constructed to visualize the distribution of the mental health parameters at baseline and follow-up.

Crude and adjusted regression models were fitted for linear and logistic regressions. For all outcomes, Adjusted Model 1 included potential covariates and Adjusted Model 2 included additional mutual adjustments for housing conditions. Results are presented for Adjusted Model 2 and results of crude and Adjusted Model 1 are presented in the eSupplement. Linear regression models were fitted for the two outcomes on a continuous scale (changes in mental well-being and QoL scores). To also examine the odds of onset of low mental well-being, low QOL and loneliness, models were fitted for participants who were at risk (only individuals who had normal levels at baseline, eFigure 1). In post hoc analyses, instead of excluding participants with low mental wellbeing, low QoL, or loneliness at baseline, we estimated relative risk ratios (RRRs) for each of the potential combinations of the binary baseline and follow-up mental health parameter in multinomial logistic regression models with the normal-normal (not lonely-not lonely) as reference outcome (e.g. for mental wellbeing: low at baseline followed by low at follow-up vs. normal at baseline followed by normal at follow-up).

For interaction analyses, linear (mental well-being and QoL) and logistic (loneliness) regression models with and without interaction terms were compared, and differences in fit tested with the likelihood ratio test. For tests indicating potential interaction (p < 0.2), we fitted stratified or joint effect models, as appropriate.

We performed complete case analyses.

Patient and public involvement

Young DNBC participants from the DNBC ambassadors group were consulted in the initial design of the COVID-19 questionnaire and provided feedback on questionnaire items prior to launching the online questionnaire. Preliminary findings were presented to the DNBC ambassadors group and the DNBC reference group. Other participants and public were not invited to participate in the study design or interpretation of results.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency via a joint notification to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences—University of Copenhagen (ref. 514-0497/20-3000, 'Standing together at a distance: how are Danish National Birth Cohort participants experiencing the corona crisis?') and performed in accordance with relevant ethical and legal regulations and guidelines. Mothers in the DNBC were enrolled with a signed and written informed consent on behalf of themselves and their offspring, until the offspring’s 18th birthday. At age 18, offspring in the DNBC were informed of their participation in the cohort, their rights, including information on how to opt out of the cohort and have their personal data deleted. For the COVID-19 questionnaire, participants who had given consent to participate in the cohort at 18, were invited to participate, and participated voluntarily in the online questionnaire.

Ethics

This study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency via a joint notification to the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences—University of Copenhagen (ref. 514-0497/20-3000, 'Standing together at a distance: how are Danish National Birth Cohort participants experiencing the corona crisis?'). The cohort is approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and the Committee on Health Research Ethics under case no. (KF) 01-471/94. Data handling in the DNBC has been approved by Statens Serum Institut (SSI) under ref. no 18/04608 and is covered by the general approval (Fællesanmeldelse) given to SSI. The 18 year follow-up was approved under ref. no 2015-41-3961. The DNBC participants were enrolled by informed consent.

Results

Participants

We included a total of 7445 of the 9211 young participants who had responded to the first COVID-19 online questionnaire and the 18-year DNBC follow-up, eFigure 1. The age range at follow up was 18 to 23 with a median age of 20 years. Approximately two thirds of the study population were female. Youth with no access to outdoor spaces were older, more educated, and more often lonely at baseline, but had less often moved compared to youth with access to outdoor space. Additionally, in the capital region more lived in households with density above median, and the other housing conditions likewise differed according to demographic characteristics Fig. 1.

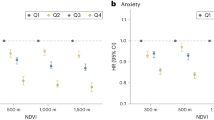

Declines in mental health during lockdown

Lower mental well-being and QoL and higher levels of loneliness were observed in the third week of the lockdown compared to before the lockdown, with higher proportions of individuals with scores indicative of possible (19.1% compared to 12.2%) or probable (2.6% compared to 1.3%) depression/anxiety, low QoL (36.6% compared to 15.6%) or being lonely (23.1% compared to 13.8%), Fig. 2.

Distribution of baseline and follow-up mental well-being (SWEMWBS) scores, QoL scores, and loneliness (No. = 7445). SWEMWBS Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale, QoL Quality of Life. (A) Kernel density plot of the distribution of mental well-being (SWEMWBS) scores: Long dash red reference for probable anxiety/depression16, short dash red reference line for indication of possible anxiety/depression, and black short reference line for indication of high mental well-being, (B) Kernel density plot of distribution QoLscores: Long dash red reference for cut-off of low QoL18, (C) Barplot of loneliness. Participants in the tails of SWEMWBS were aggregated in kernel density plots to secure non-identifiability of participants.

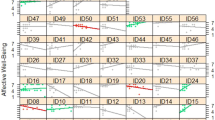

Housing conditions impact on changes in mental health

Unadjusted mean changes in mental well-being scores were highest for those with no access to outdoor spaces, Fig. 3. For this group the score was > 1 point lower, and a 1-point change on the SWEMWBS is considered to represent a clinically meaningful change16. Similarly, in the adjusted model, a lack of direct access to outdoor spaces was associated with the greatest decreases in mental well-being scores (no access vs. garden: adjusted mean difference (aMD): − 0.75 [95% CI − 1.14, − 0.36]). A stepwise decrease in odds of onset of low mental well-being was also observed going from more limited to less limited outdoor spaces. Compared to youth living in rural homes, those in urban or semi-urban homes had greater decreases in mental well-being (aMD: − 0.20 [95% CI − 0.39, − 0.02] and − 0.13[95% CI − 0.32, 0.06], respectively) and greater odds of onset of low mental well− being (aOR 1.14 [95% CI 0.94, 1.38] and aOR 1.21 [1.00, 1.48], respectively). Youth living in denser households had greater decreases in mental well-being and likewise greater odds of onset of low mental well-being than youth in non-dense households. Household composition was also associated with changes in mental well-being. Youth living with a partner had increased mental well-being compared to those living with parents. A stepwise greater odds of onset of low mental well-being was observed for youth living with parents and children/siblings, roomies/friends, and alone, compared to living with parents (Fig. 4 and eTables 1 and 2).

Changes in mental well-being (SWEMWBS) scores indicative of meaningful changes, according to housing conditions (No. = 7445). SWEMWBS: Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale. Unadjusted means for changes in mental well-being scores on the SWEMWBS, by housing conditions. Red dashed line indicates minimum change considered meaningful at the individual level on the SWEMWBS16 and incrementally darker shades of red indicate incrementally larger decreases in SWEMWBS scores.

Changes in mental well-being (A) and onset of low mental well-being (B), according to housing conditions. aMD Adjusted Mean Difference, aOR Odds Ratios, CI Confidence Intervals. aMD and 95% CI and aOR and 95% CI are presented. Population at risk of developing low mental well-being: No. (6537). Adjusted model 2: adjusted for age, sex, current education, part-time work, moving, geographical region, and mutually adjusted for housing conditions.

Decreases in QoL and onset of low QoL were associated with living in a denser household and living alone. Youth living with a partner reported increased QoL compared to youth living with parents (aMD: 0.40 [95% CI 0.22, 0.58], (Fig. 5 and eTables 3 and 4) Incident loneliness was associated with living alone and living in a denser household (aOR 2.12 [95% CI: 1.59, 2.82] and aOR 1.30 [95% CI 1.14, 1.48], respectively). (Fig. 6 and eTable 5).

Changes in QoL (A) and onset of low QoL (B) according to housing conditions. QoL Quality of Life, aMD Adjusted Mean Difference, aOR Adjusted Odds Ratios, CI Confidence Intervals. aMD and 95% CI and aOR and 95% CI are presented. Population at-risk of developing low QoL(No. = 6283). Adjusted model 2: adjusted for age, sex, current education, part-time work, moving, geographical region, and mutually adjusted for housing conditions.

Onset of loneliness, according to housing conditions. aOR Adjusted Odds Ratios, CI Confidence Intervals. aOR and 95% CI are presented. Population at-risk of developing loneliness (No. = 6418). Adjusted model 2: adjusted for age, sex, current education, part-time work, moving, geographical region, and mutually adjusted for housing conditions.

Analyses stratified by sex indicated minor sex differences that were not consistent across mental health parameters for household composition (eTable 6). Males experienced greater decreases in mental well-being when living alone or with roomies/friends and in denser households, and greater increases in loneliness when living alone. Females experienced greater decreases in QoL when living alone, but lesser decreases in QoL when living with their partner. In the joint effects model examining interactions with quarantine status, youth not quarantined and with no direct access to outdoor spaces experienced the greatest decreases in mental well-being (aMD : − 1.01 [95% CI − 1.45, − 0.57], eTable 7). Psychiatric illness did not interact with housing conditions, with a few exceptions. Youth with no psychiatric illness and living with a partner had increased QoL compared to youth without a psychiatric illness and living with parents only, suggesting an interaction with psychiatric illness (aMD: 0.38 [0.20, 0.55]) eTable 8). This may be due to the larger sample of youth without a psychiatric illness though, as the point estimate was similar for those with a psychiatric illness.

For the majority of youth for whom mental health changed from before lockdown it decreased, but for 5.3% mental well-being, for 6.1% QoL and for 7.6% loneliness improved during the lockdown. Factors associated with onset of low mental well-being, low QoL, or loneliness (no access to outdoor spaces, above median household density, and living alone) were also associated with continued poorer mental health, while these patterns were less clear for improvements in mental health (eTables 9,10,11).

Discussion

The present study shows that housing conditions during the initial national Covid-19 related lockdown influenced changes in mental health among Danish youth. A lack of access to outdoor spaces was associated with greater decreases in mental well-being. Although to a lesser extent, decreased mental well-being appeared to be associated with living in an urban or semi-urban home. Living in a denser household and living alone were also both associated with decreases in mental well-being and QoL, and with an increase in loneliness. Therefore, characteristics of the built environment and the household matters for the mental health of our youth during this pandemic.

The concepts of ‘a sense of over-crowding in the home’ and ‘escape facilities’ have previously been highlighted as important aspects of the built environment that may influence mental health20. Results from the first studies on housing and mental health in the COVID-19 pandemic, suggest that these factors may be associated with mental health during a pandemic as well9,10,11. Three cross-sectional studies conducted in Southern European countries which were severely impacted by the pandemic have assessed associations between some housing conditions on mental health during the initial Covid-19 related lockdowns. In Italy, students with moderate–severe and severe depressive symptoms lived in significantly smaller apartments without access to outdoor space, such as a balcony or a garden, and had a poor quality view10. Another study from France found that living in an urban area, having access to an outdoor space and a bigger dwelling size was positively associated with well-being (measured using the WEMWBS scores)11. A third study conducted in Portugal reported that access to a garden was related with lower depression and stress, whereas the number of people in the household was not9. In addition, a prospective study in the UK reported that being a young adult, urbanicity, and living alone were associated with greater loneliness—these results were based on a sample during the pandemic and compared levels to another sample with measures prior to the pandemic12. These studies were not, as we were, able to assess changes in mental health parameters from before to during lockdown in the same individuals, and three of them were not specific to youth9,11,12, but their findings are consistent with ours, and highlight the importance of aspects of the built environment previously known to impact mental health.

Although changes in mental health from before to during lockdown differed for females and males, only minor and inconsistent differences in the impact of housing were observed. For example, living with a partner was only associated with relatively-speaking higher QoL among females and was only associated with relatively-speaking higher mental well-being among males.

Associations between access to outdoor spaces and declines in mental well-being were stronger for youth in quarantine. Given previous findings on the disproportionately negative effects of pandemics on mental health among youth in quarantine21, this may seem counter-intuitive. Strict adherence to quarantine might have an effect that cannot be improved simply by access to outdoor spaces. For example, youth may utilize some of the outdoor spaces investigated for visiting with friends.

We suspected that youth with psychiatric illnesses would be more susceptible to the negative effects of the lockdown and that housing conditions could potentially be more strongly associated with mental health outcomes6. We only observed differences for QoL and household composition. Although youth with psychiatric illnesses in our sample have experienced greater declines in mental health on average (for further information visit coronaminds.ku.dk), our results do not suggest that these interact substantially with housing conditions. Nevertheless, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions, due to the low numbers.

Strengths and limitations

One of the main strengths of our study design is the longitudinal design with individual-level data on a large sample of youth with measures from before and during the most restrictive phases of the Danish lockdown in spring 2020. The early lockdown of Denmark effectively curbed the spread of COVID-19 and the number of deaths due to COVID-19 were low compared to other European countries at the time of our follow-up2. Therefore, it is less likely that changes in mental health outcomes were due to the concurrent levels of infection spread, as opposed to the lockdown. To our knowledge, no other studies have considered longitudinally the effect of housing conditions on youth’s mental health development before and during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Interpretation of our results deserves consideration of a few limitations. The baseline data were collected at age 18 years and three months for all participants, whereas the participants’ ages varied during the lockdown. Thus, the time elapsed between baseline and follow-up was greater for older participants. All analyses were adjusted for age, and we thereby indirectly accounted for different time between baseline and follow up. For older participants, changes in mental health parameters may be underestimated, since their baseline measures represent a younger age than the follow-up measures, and on average reporting on mental health instruments improves by age. Therefore, our estimates could be underestimated, and thereby conservative, in particular for the housing conditions where age is unevenly distributed as for access to outdoor spaces and household composition. Additionally, although we adjusted for what we consider likely to be the most important confounding variables, we cannot exclude the possibility of unmeasured and residual confounding. Access to outdoor spaces could be a proxy for other beneficial aspects of the built environment. Nonetheless, we suspect that such factors would be captured in the model (geographical region, urbanicity, household density) and would likely not have independent effects on changes in mental health.

Misclassification of housing conditions may have influenced our results. Postal codes were used to identify municipality-level degrees of urbanization. However, in a few instances postal codes may be assigned to multiple municipalities and even regions. Nevertheless, the numbers of potential misclassification due to this are minimal. Misclassification of loneliness may also have occurred, as the two items from each questionnaire, were worded slightly differently. Although identical items would have been ideal, the two items were deemed sufficiently similar to include as harmonizable variables. We also do not expect any differential misclassification according to housing conditions—that youth in different housing conditions would understand the two questionnaire items in different manners. Lastly, although we used validated scales for mental well-being and QoL, the interpretation of these as indicating new onset mental disease must be cautious, as changes on these scales may be transient.

A final important limitation to consider is the selection into the study. Less than 10% of the youth still enrolled in the DNBC contributed to this study, as a prerequisite was that they were old enough to have 18-year data and participated in the corona survey. Maternally reported household socio-occupational status collected when pregnant, prenatal smoking, maternal age and parity are all predictors for participation. It is likely that these and other factors influenced both participation and mental health, and we presume this would, if anything, have biased our results towards no association. The external generalizability of these findings must be considered in light of the predominantly female participation and the Danish context. In our study population, approximately 60% of the DNBC offspring 18 and 19 years old were living with parents at the time of responding to the online questionnaire. The vital statistics for the Danish population in 2016 indicate that this is a lower percentage than in the general population, although this may be due to a greater proportion of females, who tend to move away from home earlier22. In other countries, ages for moving away from the parental home is later23, and the relationship between housing characteristics and youth’s mental health under a pandemic might be different. In our study, 12% had moved during lockdown, and those who moved more often stayed in non-urban municipalities, had access to outdoor spaces and lived with parents. Additionally, we suspect that the effect of housing conditions on changes in mental health are likely to be more pronounced in countries with more severe and lengthy restrictions1. Future studies may elucidate this.

Conclusion

Youth’s mental health has declined during the initial stage of the COVID-19 pandemic with some youth especially vulnerable to mental health declines. Living without access to outdoor spaces, in urban or semi-urban homes, alone, or in denser households may increase onset of depression, anxiety, and loneliness. Housing conditions should be emphasized in efforts to keep youth’s mental health intact and public health professionals and policy-makers should consider the increased vulnerability of youth living alone, in denser households, and without access to outdoors spaces.

References

Flaxman, S. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7 (2020).

Clotworthy, A. et al. ‘Standing together—at a distance’: Documenting changes in mental-health indicators in Denmark during the COVID-19 pandemic. Scand. J. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494820956445 (2020).

Pierce, M. et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. Lancet Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4 (2020).

Ettman, C. K. et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in us adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw. open. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686 (2020).

Vindegaard, N. & Eriksen, B. M. COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain Behav. Immun. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.048 (2020).

Zhou, J., Liu, L., Xue, P., Yang, X. & Tang, X. Mental health response to the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Am. J. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20030304 (2020).

Fegert, J. M., Vitiello, B., Plener, P. L. & Clemens, V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 (2020).

Loades, M. E. et al. Rapid systematic review: The impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 (2020).

Moreira, P. S. et al. Protective elements of mental health status during the COVID-19 outbreak in the Portuguese population. MedRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.04.28.20080671 (2020).

Amerio, A. et al. Covid-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165973 (2020).

Haesebaert, F., Haesebaert, J., Zante, E. & Franck, N. Who maintains good mental health in a locked-down country? A French nationwide online survey of 11,391 participants. Heal. Place. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2020.102440 (2020).

Bu, F., Steptoe, A. & Fancourt, D. Who is lonely in lockdown? Cross-cohort analyses of predictors of loneliness before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.036 (2020).

Olsen, J. et al. The Danish national birth cohort–its background, structure and aim. Scand. J. Public Health. 29(4), 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1177/14034948010290040201 (2001).

Stewart-Brown, S. et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): A valid and reliable tool for measuring mental well-being in diverse populations and projects. J. Epidemiol. Community Heal. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2011.143586.86 (2011).

Koushede, V. et al. Measuring mental well-being in Denmark: Validation of the original and short version of the Warwick-Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS and SWEMWBS) and cross-cultural comparison across four European settings. Psychiatry Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.003 (2019).

Warwick Medical School. Collect, score, analyse and interpret WEMWBS. Warwick. https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/sci/med/research/platform/wemwbs/using/howto/. Published 2020. Accessed September 29, 2020.

Levin, K. A. & Currie, C. Reliability and validity of an adapted version of the cantril ladder for use with adolescent samples. Soc. Indic. Res. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0507-4 (2014).

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., et al. Social determinants of health and well-being among young pople. Heal Behav Sch Child Study Int Rep From 2009/2010 Surv. 2012.

Dijkstra, L., Poelman, H. A harmonised definition of cities and rural areas: the new degree of urbanisation. Reg Urban Policy. 2014.

Guite, H. F., Clark, C. & Ackrill, G. The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.005 (2006).

Sprang, G. & Silman, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2013.22 (2013).

Denmark S. Vital Statistics 2016.; 2017. https://www.dst.dk/Site/Dst/Udgivelser/GetPubFile.aspx?id=20714&sid=befudv2016.

Eurostat. Being young in Europe today - digital world - Statistics Explained. Eurostat Stat Explain. 2015.

Acknowledgements

The Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation and other minor grants. The DNBC Biobank has been supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation. Follow‐up of mothers and children has been supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (SSVF 0646, 271‐08‐0839/06‐066023, O602‐01042B, 0602‐02738B), the Lundbeck Foundation (195/04, R100‐A9193), The Innovation Fund Denmark 0603‐00294B (09‐067124), the Nordea Foundation (02‐2013‐2014), Aarhus Ideas (AU R9‐A959‐13‐S804), a University of Copenhagen Strategic Grant (IFSV 2012) and the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF—4183‐00594 and DFF—4183‐00152). Follow-up of mother and children in the COVID-19 data collection was supported by a grant from the Velux Foundation (Grant number 36336). Follow-up of youth in the 18 year-follow up was supported by a grant from the Independent Research Fund Denmark (DFF-4183-00594 [Close to Adult: 17-year follow-up of the Danish National Birth Cohort]).

Funding

This study was made possible by a grant from the RealDania Foundation (PRJ-2019-00020 ‘Indoor environment and child health’) and by a grant from the Velux Foundation (grant number 36336, ‘Standing together at a distance—how Danes are handling the corona crisis’). The funders of the study had no part in the conception or design of the study, or in the decision to publish.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.G., A.C.K., T.L.N., A.M.N.A. and K.S.L. conceived and designed the study. J.G. was primarily responsible for conducting the analyses and drafting the manuscript. J.G., A.C.K., A.J., A.M.N.A. and K.S.L. were involved in the data collection and data management of the COVID-19 questionnaire. All authors contributed to the analytical approach and interpretation of the data, revisions of the manuscript, and submission of the final manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted. JG is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Groot, J., Keller, A., Joensen, A. et al. Impact of housing conditions on changes in youth’s mental health following the initial national COVID-19 lockdown: a cohort study. Sci Rep 12, 1939 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04909-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-04909-5

This article is cited by

-

Trajectories of child mental health, physical activity and screen-time during the COVID-19 pandemic considering different family situations: results from a longitudinal birth cohort

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.