Abstract

Assessing the taxonomic importance of the suture line in shelled cephalopods is a key to better understanding the diversity of this group in Earth history. Because fossils are subject to taphonomic artifacts, an in-depth knowledge of well-preserved modern organisms is needed as an important reference. Here, we examine the suture line morphology of all known species of the modern cephalopods Nautilus and Allonautilus. We applied computed tomography and geometric morphometrics to quantify the suture line morphology as well as the conch geometry and septal spacing. Results reveal that the suture line and conch geometry are useful in distinguishing species, while septal spacing is less useful. We also constructed cluster trees to illustrate the similarity among species. The tree based on conch geometry in middle ontogeny is nearly congruent with those previously reconstructed based on molecular data. In addition, different geographical populations of the same species of Nautilus separate out in this tree. This suggests that genetically distinct (i.e., geographically isolated) populations of Nautilus can also be distinguished using conch geometry. Our results are applicable to closely related fossil cephalopods (nautilids), but may not apply to more distantly related forms (ammonoids).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Cephalopoda are marine mollusks including both extinct (e.g., orthocerids, bactritoids, ammonoids, and belemnoids) and modern taxa (squids, octopuses, and nautiloids). Since their origin in the Cambrian1, they have played an important ecological role in the oceans, occupying most likely multiple trophic levels2,3,4,5,6. In the fossil record, some cephalopods such as ammonoids are abundant and widely distributed, thus making them ideal model organisms to understand diversification dynamics. One of the apomorphies of externally shelled cephalopods is the chambered conch consisting of a gas-filled phragmocone, providing buoyancy, and a body chamber, accommodating the soft tissue. The phragmocone chambers are septated by partitions called septa; the intersection of the septum and the outer shell wall is known as the suture line. The morphology of septa—and, therefore, the suture line—varies widely among and within cephalopod taxa at different geological times. For example, it is relatively simple in Paleozoic taxa including plectronocerids, oncocerids, and orthocerids, while it is significantly more complex in various clades of ammonoids in the Mesozoic. The complex sutural (septal) morphology is often attributed to constraints related to biomechanics or physiology7,8,9,10. Most recently, Lemanis et al.11,12 concluded that complex septal morphology was likely not an adaptation to increase the resistance against hydrostatic pressure.

The suture line morphology differs at high taxonomic levels in ammonoids and nautiloids. Thus, documenting the morphology of the suture line is traditionally an important part of carrying out taxonomic studies of fossil cephalopods13,14. In some cases (e.g., where only a few characters are available), the morphology of the suture line (as well as septal spacing) is an important character to diagnose species15,16,17,18. However, despite wide application in cephalopod taxonomy, the taxonomic utility of the suture line is still under debate, although paleontologists have attempted to quantitatively examine the morphology of the suture line in ammonoids for decades19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26. One of the issues is that, conventionally, the suture line is translated from 3- to 2-dimensional space by hand. This introduces artifacts depending on the researcher. Secondly, fossil material is always subject to time-averaging and post-mortem transport to some degree, introducing another source of variation. Demonstrating the utility of the suture line in cephalopod taxonomy is, thus, of great importance, considering its potential application to a wide range of phragmocone-bearing cephalopods.

Among cephalopod groups, the nautilids Nautilus and Allonautilus—often dubbed “living fossils”—are the only modern ectocochleate taxa that possess a phragmocone. The study of modern nautilids reduces time-averaging to a minimum (at least at time scales of more than tens of years). In addition, specimens are widely available in museum collections from many localities. While an increasing number of studies have examined the genetics of these animals, shedding new light on their phylogeny and phylogeography27,28,29,30,31,32, our knowledge of the morphology of their shells has not been substantially updated since the 1990’s. Modern nautilids are now protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Fortunately, modern analytical methods, such as computed tomography, allow for the examination of museum collections in detail without destruction33,34.

In this study, we investigate the morphology of the suture line in modern nautilids in detail by applying high-resolution computed tomography and geometric morphometrics. We aim to answer the following questions: (1) To what degree does the morphology of the suture line differ among species of modern nautilids? (2) How does the variation in the morphology of the suture line compare to that of other conch parameters such as conch geometry and septal spacing? (3) Is the suture line a useful diagnostic character for cephalopods compared to other conch parameters? (4) How do our results based on these conch parameters compare to those from molecular data?

Methods

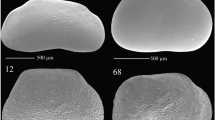

We studied two specimens of each of the following eight modern nautilid species: Allonautilus perforatus (Conrad, 1847) from Indonesia, Allonautilus scrobiculatus (Sowerby, 1849) from Papua New Guinea, Nautilus belauensis Saunders, 1981 from Palau, Nautilus macromphalus Sowerby, 1849 from New Caledonia, Nautilus pompilius Linnaeus, 1758 from Papua New Guinea and the Philippines, Nautilus pompilius suluensis Habe and Okutani, 1988 from the Philippines, Nautilus repertus Iredale, 1944 from Western Australia, and Nautilus stenomphalus Sowerby, 1848 from Lizard Island, Australia. Brief descriptions of each of these species are summarized in the Supplementary Note. Most of the specimens were caught live between 1970 and 2010. The sex was recorded for a few individuals (see Table 1 for details). All specimens were identified as nearly to fully mature because all specimens show a crowding of the last few septa and/or exhibit a black band at the aperture35,36. Most specimens are housed in the American Museum of Natural History (with the abbreviation AMNH); the specimens of N. pompilius from the Philippines are in the National Museum of Nature and Science, Japan (with the abbreviation NMNS PM).

We applied computed tomography in order to three-dimensionally reconstruct the conchs. A total of 16 specimens were CT-scanned at the Microscopy and Imaging Facility of the American Museum of Natural History and two specimens of N. pompilius from the Philippines were CT-scanned at the Port and Airport Research Institute, Japan. The image stacks obtained were segmented in Amira 2020 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to export the interior surfaces of all chambers. Note that we excluded the earliest formed chamber (chamber 1) from our analyses due to potential artifacts resulting from limited scan resolution. To quantify the morphology of the suture line, we applied three-dimensional geometric morphometrics. Accordingly, we designated a total of 20 points of reference (so-called ‘landmarks’) with equidistant intervals along the edge of each chamber (i.e., suture line) in MATLAB (MathWorks). The landmarks for each chamber were slid along the outline of a reference individual to minimize the bending energy (sliding semi-landmark method37; Fig. 1A). Subsequently, we normalized and registered the landmark coordinates of each chamber according to its centroid size using the generalized Procrustes method38. The Procrustes residuals were then analyzed using principal components analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensions of the data. We also examined two other morphological parameters—conch geometry and septal spacing. Conch geometry is the cross-sectional shape of a conch (Fig. 1B). We regard this parameter as the most commonly used character in the taxonomy of (mainly fossil) ectocochleate cephalopods. It is generally quantified using a linear morphometric approach39,40,41. We applied two-dimensional geometric morphometrics to analyze the conch geometry. First, we produced cross-sections of the conch every 45°, starting with the aperture (see Tajika and Klug33 for details), which enabled us to examine the morphology of ~ 20 ontogenetic points per specimen. Then, we designated a total of 40 landmarks with equidistant intervals along the shell on the whorl cross-section (Fig. 1B; compare Tajika et al.41). These landmarks were analyzed with the same methodology as the suture line. It should be noted that the conch geometry quantified here represents the morphology of the internal mold, the most common type of preservation in fossil ectocochleate cephalopods. Lastly, septal spacing was measured as the rotational angle between septa through ontogeny (Fig. 1C).

Analyzed morphological parameters (Nautilus pompilius suluensis Habe and Okutani, 1988; AMNH 93768). (A) Suture line (adoral view). A total of 20 landmarks were placed on the edge of the chamber. (B) Conch geometry (cross-sectional morphology). (C) Septal spacing (septal rotational angle). Scale bars = 10 mm.

To visualize the similarity of each morphological character between species/populations, we constructed trees for the three morphological parameters using the neighbor-joining method42 and the Euclidian distances in PC space (based on all PCs). Comparisons of trees were carried out at three different ontogenetic stages. In this study, we used the conch diameters of 20 and 50 mm and maximal conch diameter as a proxy for the three different ontogenetic stages pre-hatching, middle ontogeny, and maturity. Accordingly, we picked two data points that are the closest to each of the conch diameters in each specimen. The specific ranges of each ontogenetic stage are approximately 18–21 mm (pre-hatching) and 45–55 mm (middle ontogeny; see Table 1 for maximal conch diameter of each specimen). Additionally, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine whether or not septal spacing significantly differs between species and populations. The analysis of variance was followed by multiple-comparison tests to determine which pairs of species/population are significantly different. These statistical tests were carried out at three different ontogenetic stages: (1) pre- hatching stage (conch diameter < 30 mm), (2) juvenile–submature stage (conch diameter ≥ 30 until the third chamber from the last), (3) mature stage (last two chambers). We conducted these analyses using the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox™ of MATLAB.

Results

Figure 2A shows the results of PCA for suture line morphology. PC1 accounts for 63.0% of the total variance, PC2 for 20.6%, and PC3 for 3.9%. In the graph, all species share a similar ontogenetic pattern in the change of PC scores. PC1 increases rapidly until about a conch diameter of 30–40 mm after which it increases more gradually (Fig. 2C). PC2 shows a rapid decrease until about a conch diameter of 10 mm, followed by a rapid increase until a conch diameter of 30 mm (Fig. 2D). Then, it decreases steadily until the end of ontogeny. The ontogenetic changes of PC1 and PC2 indicate high morphological variation through ontogeny.

Results of morphological analysis. Points from the same individual are connected with a line. Arrows indicate the direction of growth. (A) PCA plot graph for sutural morphology. (B) PCA plot graph for conch geometry (cross-sectional morphology). (C) PC1 plotted against conch diameter for sutural morphology. (D) PC2 plotted against conch diameter for sutural morphology. (E) PC1 plotted against conch diameter for conch geometry. (F) PC2 plotted against conch diameter for conch geometry. (G) Septal spacing (septal rotational angle) plotted against chamber number. (H) Septal spacing (septal rotational angle) plotted against conch diameter (mm).

The results of PCA for conch geometry (cross-sectional morphology) are shown in Fig. 2B. In conch geometry, PC1 accounts for 65.1% of the total variance, PC2 for 24.0%, and PC3 for 6.4%. Similar to the morphology of the suture line, all species share a similar pattern in the change of PC scores for conch geometry through ontogeny. However, the patterns between suture line morphology and conch geometry differ. In conch geometry, PC1 increases until it reaches a plateau at a diameter of approximately 40 mm (Fig. 2E). PC2 rapidly increases until a diameter of 25 mm, followed by a sharp decrease; the decreasing trend becomes attenuated at a diameter of about 40 mm (Fig. 2F). The measurements of septal spacing are plotted in Fig. 2G,H. Septal spacing shows a steep increase followed by a steep decrease at chamber 7 or 8, which corresponds to the point of hatching43. Subsequently, septal spacing becomes relatively stable, with septa regularly spaced at 20–30°. Septal spacing decreases at the last septum or over the last few septa.

To illustrate the similarity among species, we constructed trees for each morphological character based on the PC scores (suture line, conch geometry) and measurements (septal spacing). As shown in Fig. 3, individuals at approximately the same ontogenetic stage form the largest clusters (pre-hatching versus post-hatching stages) rather than individuals of the same species. This suggests that morphological comparisons need to be made at a similar ontogenetic stage. Accordingly, we constructed trees based on the conch parameters using two chambers and two cross-sections at three different ontogenetic stages: diameters of about 20 mm (before hatching; Fig. 4), 50 mm (middle ontogeny; Fig. 5), and maturity (Fig. 6). In all examined characters, it is clear that the different species are less easily distinguished at the pre-hatching stage than at other ontogenetic stages (Figs. 4C, 5C, 6C). In addition, some taxa such as the two species of Allonautilus (A. scrobiculatus and A. perforatus) and N. macromphalus tend to form a single cluster, respectively, with a few exceptions for suture line and conch geometry (Figs. 4A,B and 5A,B). The morphological differences between species are visualized in Supplementary Video S1 and Supplementary Fig. S1. By contrast, taxa appear to be more randomly distributed with respect to septal spacing (Fig. 6). Figure 7 shows the range and distribution of septal spacing at different ontogenetic stages. The results of ANOVA reveal that there is no significant difference (p > 0.05; p-values available in Supplementary Table S1) at the pre-hatching (conch diameter < 30 mm) and adult stages but that the difference is significant at the middle ontogenetic stage (Supplementary Table S1). Multiple comparison tests demonstrate that a significant difference occurs both within- and between taxa at this stage (Fig. 7; Supplementary Table S1). In the following section, we will discuss the taxonomic implications in detail.

Discussion

Potential artifacts

Although the application of computed tomography has become relatively common, there are some potential artifacts that may affect the results of our study. For instance, although the make-up of our specimens is entirely calcium carbonate with some organic remains, and the specimens were scanned at high resolution, the partial volume effect (PVE) results in a certain degree of error when reconstructing the volume44. In our study, the morphological analysis of the suture line is subject to this artifact because we needed to three-dimensionally reconstruct the chambers. As such, we estimated the difference between the actual and reconstructed conch volume using a silica sphere that was scanned together with the specimens. We found that the difference is ~ 10% in the examined specimens, implying that the reconstructed volume is not exactly precise. However, this is true for all specimens and, as a result, we consider that this artifact does not significantly affect our comparisons among the different specimens. Another possible error arises when there are some deposits such as cameral remains and broken shells within the conch. In this case, instead of relying on an automatic segmentation tool in Amira, we needed to manually segment the CT-images, which usually introduces some artifacts. In our specimens, we found a few chambers with infills. Nevertheless, we think that this artifact is quite negligible because we obtained a relatively distinctive ontogenetic pattern in our results without outliers (Fig. 2).

Taxonomy

It should be noted that the validity of some of the studied nautilid taxa has been occasionally debated, although we explicitly excluded dubious species (sensu Saunders45) from our study. Most modern nautilid species were established based on their conch morphology, color pattern, and soft tissue anatomy. Yet, recent genetic studies have presented divergent views. For instance, Vandepas et al.30 studied Nautilus belauenesis, N. repertus, and N. stenomphalus using mitochondrial markers, which suggested that these species are simply variants of N. pompilius. Combosch et al.27 discovered that there is no genomic admixture between the geographic populations of Nautilus species in the South Pacific, Coral Sea, and Indo-Pacific. They concluded that previously described species are not concordant with their results and that there may be cryptic species that are geographically isolated (i.e., there are species that are only separable based on molecular data). In the following, we discuss whether such species with similar genetic distances show clear morphological differences.

Similarity of the three morphological parameters among taxa

As briefly discussed in the results section, the three conch parameters differ in how useful they are in distinguishing species. For all three characters examined, the pre-hatching stage appears less useful than the other ontogenetic stages in distinguishing species and genera: all taxa tend to be more or less randomly distributed in the tree (Figs. 4C, 5C, 6C). This is especially conspicuous in septal spacing at this stage in which there is no significant difference in the mean value among taxa (Fig. 7A; Supplementary Table S1). With respect to the suture line (Fig. 4C), individuals within the same species at this stage tend to cluster with one another, with a few outliers. This implies that the intraspecific variation of suture line morphology is relatively high and that the morphology of one species may overlap with that of another before hatching. This also holds true for conch geometry at this stage (Fig. 5C).

In middle ontogeny (i.e., conch diameter ≈ 50 mm), the species are more clearly separated (Figs. 4B and 5B) except in septal spacing (Fig. 6B). When comparing the trees for suture line and conch geometry, the latter exhibits a clearer separation of species. For instance, although Nautilus repertus, N. belauensis, and N. pompilius appear in the two largest clusters in Fig. 4B, they are more or less separated in Fig. 5B. Also, both species of Allonautilus can more readily be distinguished using conch geometry than suture line at this ontogenetic stage. Our results are similar to the phylogeographic trees constructed by Combosch et al.27 and Vandepas et al.30 in that Allonautilus scrobiculatus and N. macromphalus form distinctive clusters. Furthermore, three geographic clusters of Nautilus from the South Pacific, Coral Sea, and Indo-Pacific shown by Combosch et al. are apparent in our results for conch geometry (Fig. 5B), although this separation is not visible for the suture line. This similarity with Combosch et al.27 implies that the five distinct clades that are potentially new Nautilus species may not, after all, be cryptic. As far as septal spacing is concerned, some species can be distinguished (Figs. 6B, 7B), but the fact that the ranges of some species—even genera—overlap, with high intraspecific variation (e.g., N. belauensis in Fig. 7B) suggests that septal spacing is not useful in middle ontogeny.

As in middle ontogeny, the suture line and conch geometry appear to be better characters than septal spacing to distinguish species in late ontogeny (Figs. 4A, 5A, 6A). Regarding the suture line, species are better separated at maturity than at the juvenile stage. Allonautilus perforatus and A. scrobiculatus are distinguished from one another although one specimen of A. perforatus is morphologically closer to Nautilus macromphalus than to A. scrobiculatus (Fig. 4A). The mixture of A. perforatus and N. macromphalus suggests that the morphological difference in suture line between the two taxa is not as conspicuous as that of external conch morphology. All Nautilus species except N. macromphalus are difficult to separate out. Regarding conch geometry, species do not separate out as readily as at the middle ontogenetic stage, although there are some species-specific patterns (Fig. 5A). The species of Allonautilus form a cluster and one individual of N. macromphalus lies outside the cluster for N. macromphalus and both species of Allonautilus (Fig. 5A). As far as the other Nautilus species are concerned, the morphological variation of each species seems to hamper separation in late ontogeny. Septal spacing at maturity does not significantly differ in any species (Figs. 6A, 7C), suggesting that septal spacing is not a useful diagnostic character throughout ontogeny. This indicates that septal formation may not be affected by environmental factors such as food supply and water chemistry, resulting from the different habitats of modern nautilids.

Morphological similarity and phylogeny

Some researchers have suggested that the suture line may be a better character than conch geometry for reconstructing the phylogeny of ectocochleate cephalopods as the latter is highly homoplastic (see Klug and Hoffmann46 and references therein). This is usually the case for at/above generic level in ammonoids. Although it is not our purpose to reconstruct the phylogeny of modern nautilids using morphological characters, we briefly discuss our result in the context of phylogeny.

As mentioned above, all modern nautilid species were established based on morphology, and thus morphological differences should be visible among species. However, most species cannot be distinguished in our results at early and adult ontogenetic stages, with the exception of Nautilus macromphalus and the two species of Allonautilus. The differences in Nautilus species are apparent only for conch geometry in middle ontogeny. Although the reason behind this is unclear, it may be rooted in morphological constraints at maturity regarding reproductions, which are shared by different species (see the discussion of morphogenetic countdown at maturity in Tajika and Klug33 and Seilacher and Gunji47). Additionally, species specific characters may not develop before hatching. When comparing our results and previous molecular studies, the tree based on conch geometry in middle ontogeny is most similar to the phylogeographic tree of Vandepas et al.30 and Combosch et al.27 (for a simiplified phylogenetic tree by Combosch et al.27 see Supplementary Fig. S2). These results suggest that conch morphology—particularly in middle ontogeny—may yield a robust phylogeny similar to that reconstructed using molecular data. Further research with more specimens and more data (e.g., sex, habitat) and more rigorous methodology for phylogenetic reconstruction are needed.

Implications for taxonomy of fossil ectocochleate cephalopods

Our results revealed that (1) intraspecific variation is higher than interspecific variation at a particular ontogenetic stage, (2) modern nautilid species can be separated out based on conch geometry (cross-sectional morphology) in middle ontogeny, and (3) it is difficult to distinguish modern species based on the suture line with the exception of Nautilus versus Allonautilus.

We suspect that our results also apply to fossil nautilids. Tajika et al.41 investigated the ontogeny of Late Cretaceous Eutrephoceras dekayi (Morton, 1834) and modern Nautilus pompilius. They discovered a similar ontogenetic pattern in whorl expansion rate, whorl width index, and septal spacing index between the two taxa despite the fact that the two taxa lived in different environments at different times (i.e., E. dekayi in shallow water epicontinental seas in North America during the Late Cretaceous vs. N. pompilius in much deeper water on steep forereef slopes in the Philippines today). Their similar ontogenetic trajectories in morphological space may suggest a similar evolutionary heritage rather than an adaptation to a particular environment. Thus, we presume that our results may be applicable to at least some groups of fossil nautilids. As mentioned above, however, detailed morphological studies are largely lacking in fossil nautilids with few exceptions41,48,49 and, therefore, additional data on the conch morphology (e.g., siphuncular position, siphunclular thickness, soft tissue attachment, classical conch parameters) through ontogeny are needed to further discuss the potential application in fossil forms.

In contrast to nautilids, ammonoids are known to possess a remarkably diverse array of conch shapes. They also exhibit high intraspecific variation, possibly in response to variation in their environment50,51,52,53. As a result, the ontogenetic trajectory in morphological space of ammonoids is highly variable54,55,56,57. Taking these observations into consideration, it implies that the various patterns of conch morphology in ammonoids also differ from those in modern nautilids. Although the phenotypic plasticity and ecophenotypic variability of the suture line in ammonoids have never been studied in detail to our knowledge, we cannot determine whether the suture line is the most useful character in distinguishing ammonoid species with our current data. As evidenced by our results, even a slight difference in conch diameter can significantly affect the suture line. We, therefore, strongly suggest examining the suture line at the same conch diameter. Our data also demonstrate that even distantly related nautilid species (e.g., Nautilus macromphalus and Allonautilus scrobiculatus) exhibit similar suture lines and, thus, we suggest caution in using the suture line as the only character in taxonomic studies.

Data availability

Results of statistical tests and raw data are available in Supplementary Table S1.

References

Kröger, B., Vinther, J. & Fuchs, D. Cephalopod origin and evolution: A congruent picture emerging from fossils, development and molecules. BioEssays 33, 602–613 (2011).

Keupp, H. Sublethal punctures in body chambers of Mesozoic ammonites (forma aegra fenestra nf), a tool to interpret synecological relationships, particularly predator-prey interactions. Paläontol. Z. 80, 112–123 (2006).

Kruta, I., Landman, N., Rouget, I., Cecca, F. & Tafforeau, P. The role of ammonites in the Mesozoic marine food web revealed by jaw preservation. Science 331, 70–72 (2011).

Tajika, A., Nützel, A. & Klug, C. The old and the new plankton: Ecological replacement of associations of mollusc plankton and giant filter feeders after the Cretaceous?. PeerJ 6, e4219 (2018).

Jenny, D. et al. Predatory behaviour and taphonomy of a Jurassic belemnoid coleoid (Diplobelida, Cephalopoda). Sci. Rep. 9, 7944 (2019).

Klug, C., Schweigert, G., Tischlinger, H. & Pochmann, H. Failed prey or peculiar necrolysis? Isolated ammonite soft body from the Late Jurassic of Eichstätt (Germany) with complete digestive tract and male reproductive organs. Swiss J. Palaeontol. 140, 1–14 (2021).

Hassan, M. A., Westermann, G. E., Hewitt, R. A. & Dokainish, M. A. Finite-element analysis of simulated ammonoid septa (extinct Cephalopoda): Septal and sutural complexities do not reduce strength. Paleobiology 28, 113–126 (2002).

Kröger, B. On the efficiency of the buoyancy apparatus in ammonoids: Evidences from sublethal shell injuries. Lethaia 35, 61–70 (2002).

Pérez-Claros, J. A. Allometric and fractal exponents indicate a connection between metabolism and complex septa in ammonites. Paleobiology 31, 221–232 (2005).

Daniel, T. L., Helmuth, B. S., Saunders, W. B. & Ward, P. D. Septal complexity in ammonoid cephalopods increased mechanical risk and limited depth. Paleobiology 23, 470–481 (1997).

Lemanis, R., Zachow, S. & Hoffmann, R. Comparative cephalopod shell strength and the role of septum morphology on stress distribution. PeerJ 4, e2434 (2016).

Lemanis, R. The ammonite septum is not an adaptation to deep water: Re-evaluating a centuries-old idea. Proc. R. Soc. B 287, 20201919 (2020).

Arkell, W., Furnish, W. & Kummel, B. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part L: Mollusca 4, Cephalopoda, Ammonoidea 490 (Geological Society of America, 1957).

Teichert, C. et al. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology. Part K: Mollusca 3. Cephalopoda-General Features, Endoceratoidea-Actinoceratoidea-Nautiloidea Bacteritoidea (Geological Society of America/University of Kansas Press, 1964).

Pictet, F.-J. Description des mollusques fossiles qui se trouvent dans les grès verts des environs de Genève (1847).

Gauthier, H. Volume IV. Céphalopodes Crétacés in Révision critique de la Paléontologie Française d'Alcide d'Orbigny (ed J.-C. Fischer) 1–292 (2006).

Sharpe, D. Description of the Fossil Remains of Mollusca Found in the Chalk of England. Part I Cephalopoda. Monogr. Palaeontograph. Soc 7, 1–26 (1853).

Wiedmann, J. Zur Stammesgeschichte jungmesozoischer Nautiliden unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der iberischen Nautilinae D’ ORB. Palaeontogr. Abt. A 115, 144–206 (1960).

Pérez-Claros, J. A., Palmqvist, P. & Olóriz, F. First and second orders of suture complexity in ammonites: A new methodological approach using fractal analysis. Math. Geol. 34, 323–343 (2002).

Allen, E. G. New approaches to Fourier analysis of ammonoid sutures and other complex, open curves. Paleobiology 32, 299–315 (2006).

Allen, E. G. Understanding Ammonoid Sutures: New Insight into the Dynamic Evolution of Paleozoic Suture Morphology in Cephalopods Present and Past: New Insights and Fresh Perspectives (eds. Landman, N. H., Davis, R. A. & Mapes R. H.) 159–180 (Springer, 2007).

Gildner, R. F. A Fourier method to describe and compare suture patterns. Palaeontol. Electron. 6, 12 (2003).

Saunders, W. B. & Work, D. M. Shell morphology and suture complexity in Upper Carboniferous ammonoids. Paleobiology 22, 189–218 (1996).

Ubukata, T., Tanabe, K., Shigeta, Y., Maeda, H. & Mapes, R. H. Eigenshape analysis of ammonoid sutures. Lethaia 43, 266–277 (2010).

Ubukata, T., Tanabe, K., Shigeta, Y., Maeda, H. & Mapes, R. H. Wavelet analysis of ammonoid sutures. Palaeont. Electron. 17, 9A (2014).

Yacobucci, M. M. & Manship, L. L. Ammonoid septal formation and suture asymmetry explored with a geographic information systems approach. Palaeontol. Electron. 14, 17 (2011).

Combosch, D. J., Lemer, S., Ward, P. D., Landman, N. H. & Giribet, G. Genomic signatures of evolution in Nautilus—An endangered living fossil. Mol. Ecol. 26, 5923–5938 (2017).

Bonnaud, L., Ozouf-Costaz, C. & Boucher-Rodoni, R. A molecular and karyological approach to the taxonomy of Nautilus. C.R. Biol. 327, 133–138 (2004).

Sinclair, B., Briskey, L., Aspden, W. & Pegg, G. Genetic diversity of isolated populations of Nautilus pompilius (Mollusca, Cephalopoda) in the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisheries 17, 223–235 (2007).

Vandepas, L. E., Dooley, F. D., Barord, G. J., Swalla, B. J. & Ward, P. D. A revisited phylogeography of Nautilus pompilius. Ecol. Evol. 6, 4924–4935 (2016).

Williams, R. C. et al. The genetic structure of Nautilus pompilius populations surrounding Australia and the Philippines. Mol. Ecol. 24, 3316–3328 (2015).

Wray, C. G., Landman, N. H., Saunders, W. B. & Bonacum, J. Genetic divergence and geographic diversification in Nautilus. Paleobiology 21, 220–228 (1995).

Tajika, A. & Klug, C. How many ontogenetic points are needed to accurately describe the ontogeny of a cephalopod conch? A case study of the modern nautilid Nautilus pompilius. PeerJ 8, e8849 (2020).

Tajika, A., Morimoto, N., Wani, R. & Klug, C. Intraspecific variation in cephalopod conchs changes during ontogeny: Perspectives from three-dimensional morphometry of Nautilus pompilius. Paleobiology 44, 118–130 (2018).

Saunders, W. B. & Spinosa, C. Sexual dimorphism in Nautilus from Palau. Paleobiology 4, 349–358 (1978).

Ward, P. D. The Natural History of Nautilus (Allen and Unwin, 1987).

Gunz, P., Mitteroecker, P. & Bookstein, F. L. Semilandmarks in three dimensions in Modern morphometrics in physical anthropology (ed. Slice, D.) 73–98 (Springer, 2005).

Bookstein, F. L. Morphometric Tools for Landmark Data: Geometry and Biology (Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Korn, D. A key for the description of Palaeozoic ammonoids. Fossil Rec. 13, 5–12 (2010).

Klug, C. et al. Describing ammonoid conchs in Ammonoid Paleobiology: From anatomy to ecology (eds. Klug, C. et al.) 3–24 (Springer, 2015).

Tajika, A., Landman, N. H., Morimoto, N., Ikuno, K. & Linn, T. Patterns of intraspecific variation through ontogeny: A case study of the Cretaceous nautilid Eutrephoceras dekayi and modern Nautilus pompilius. Palaeontology 63, 807–820 (2020).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: A new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Landman, N. H., Rye, D. M. & Shelton, K. L. Early ontogeny of Eutrephoceras compared to Recent Nautilus and Mesozoic ammonites: Evidence from shell morphology and light stable isotopes. Paleobiology 9, 269–279 (1983).

Hoffmann, R. et al. Non-invasive imaging methods applied to neo- and paleo-ontological cephalopod research. Biogeosciences 11, 2721–2739. https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-11-2721-2014 (2014).

Saunders, W. B. The species of Nautilus in Nautilus The Biology and Paleobiology of a Living Fossil (eds. Saunders, B. W. & Landman, N. H.) 35–52 (Springer, 1987).

Klug, C. & Hoffmann, R. Ammonoid septa and sutures in Ammonoid Paleobiology: From anatomy to ecology (eds. Klug, C. et al.) 45–90 (Springer, 2015).

Seilacher, A. & Gunji, P. Y. Morphogenetic countdowns in heteromorph shells. Neues Jb. Geol. Paläontol. Abh. 190, 237–265 (1993).

Landman, N. H. et al. Nautilid nurseries: Hatchlings and juveniles of Eutrephoceras dekayi from the lower Maastrichtian (Upper Cretaceous) Pierre Shale of east-central Montana. Lethaia 51, 48–74 (2018).

Wani, R. & Ayyasami, K. Ontogenetic change and intra-specific variation of shell morphology in the Cretaceous nautiloid (Cephalopoda, Mollusca) Eutrephoceras clementinum (d’Orbigny, 1840) from the Ariyalur area, southern India. J. Paleontol. 83, 365–378 (2009).

Wilmsen, M. & Mosavinia, A. Phenotypic plasticity and taxonomy of Schloenbachia varians (J. Sowerby, 1817) (Cretaceous Ammonoidea). Paläontol. Z. 85, 169–184 (2011).

Kawabe, F. Relationship between mid-Cretaceous (upper Albian–Cenomanian) ammonoid facies and lithofacies in the Yezo forearc basin, Hokkaido, Japan. Cretac. Res. 24, 751–763 (2003).

Ikeda, Y. & Wani, R. Different Modes of Migration Among Late Cretaceous Ammonoids in Northwestern Hokkaido, Japan: Evidence from the Analyses of Shell Whorls. J. Paleontol. 86, 605–615 (2012).

Landman, N. H. & Waage, K. M. Morphology and environment of Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) scaphites. Geobios 26, 257–265 (1993).

Korn, D. & Klug, C. Conch form analysis, variability, morphological disparity, and mode of life of the Frasnian (Late Devonian) ammonoid Manticoceras from Coumiac (Montagne Noire, France) in Cephalopods present and past: new insights and fresh perspectives (eds. Landman, N. H., Davis, R. A. & Mapes R. H.) 57–85 (Springer, 2007).

Korn, D. Goniatites sphaericus (Sowerby, 1814), the archetype of Palaeozoic ammonoids: A case of decreasing phenotypic variation through ontogeny. Paläontologische Zeitschrift 91, 337–352 (2017).

Korn, D., Bockwinkel, J. & Ebbighausen, V. The Late Devonian ammonoid Mimimitoceras in the Anti-Atlas of Morocco. Neues Jb. Geol. Paläontol. Abh. 275, 125–150 (2015).

Morón-Alfonso, D. A. Exploring the paleobiology of ammonoids (Cretaceous, Antarctica) using non-invasive imaging methods. Palaeontol. Electron. https://doi.org/10.26879/1007 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Morgan Chase and Andrew Smith (American Museum of Natural History) for CT-scanning most of the studied specimens. Yasunari Shigeta (National Museum of Nature and Science, Japan) is thanked for providing access to the specimens of N. pompilius in his care. Kozue Nishida (University of Tsukuba) helped CT-scanning some of the specimens. Meaningful discussions with Emanuel Tschopp (University of Hamburg) and Kei Sato (Waseda University) are greatly appreciated. We are also greatful to Bushra Hussaini (American Museum of Natural History) and Mariah Slovacek (formerly AMNH) for locating the specimens in the AMNH collections. Many of the studied specimens were donated by Royal Mapes (Ohio) and the late Bruce Saunders (Bryn Mawr). AT was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Research Fellow, Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (grant nrs. 20J00376 and 21K14028), and Showa Seitoku Memorial Foundation Biology Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.T. and N.L. wrote the paper. A.T. produced the tomographic data. A.T. and N.M. analyzed the tomographic data. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tajika, A., Morimoto, N. & Landman, N.H. Significance of the suture line in cephalopod taxonomy revealed by 3D morphometrics in the modern nautilids Nautilus and Allonautilus. Sci Rep 11, 17114 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96611-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-96611-1

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.