Abstract

Patient-specific and lesion-specific computational simulation of bifurcation stenting is an attractive approach to achieve individualized pre-procedural planning that could improve outcomes. The objectives of this work were to describe and validate a novel platform for fully computational patient-specific coronary bifurcation stenting. Our computational stent simulation platform was trained using n = 4 patient-specific bench bifurcation models (n = 17 simulations), and n = 5 clinical bifurcation cases (training group, n = 23 simulations). The platform was blindly tested in n = 5 clinical bifurcation cases (testing group, n = 29 simulations). A variety of stent platforms and stent techniques with 1- or 2-stents was used. Post-stenting imaging with micro-computed tomography (μCT) for bench group and optical coherence tomography (OCT) for clinical groups were used as reference for the training and testing of computational coronary bifurcation stenting. There was a very high agreement for mean lumen diameter (MLD) between stent simulations and post-stenting μCT in bench cases yielding an overall bias of 0.03 (− 0.28 to 0.34) mm. Similarly, there was a high agreement for MLD between stent simulation and OCT in clinical training group [bias 0.08 (− 0.24 to 0.41) mm], and clinical testing group [bias 0.08 (− 0.29 to 0.46) mm]. Quantitatively and qualitatively stent size and shape in computational stenting was in high agreement with clinical cases, yielding an overall bias of < 0.15 mm. Patient-specific computational stenting of coronary bifurcations is a feasible and accurate approach. Future clinical studies are warranted to investigate the ability of computational stenting simulations to guide decision-making in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and improve clinical outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary bifurcations remain one of the most challenging lesion subsets in interventional cardiology with lower procedural success rates than non-bifurcations, and increased rates of adverse cardiac events, ranging between 15 and 20% at 6 months to 1 year post intervention1. The stenting technique and the associated biomechanical environment play a dominant role in the restenosis propensity of this type of lesions1,2,3. Consideration of patient-specific anatomic parameters and local physiologic/biomechanical factors has the potential to optimize bifurcation stenting.

In the era of powerful computers, patient-specific computational simulation of bifurcation stenting can provide individualized pre-procedural planning and improvement of outcomes1. Computational simulations could guide percutaneous interventions with incremental information to the anatomical and functional assessment of coronary artery disease in the catheterization laboratory4. Computational stenting models can reproduce controversial “what if” scenarios in a 3D environment and in a cost- and time-effective fashion, elucidating the events occurring during the stenting procedure5. Computational stenting can characterize the local biomechanical microenvironment pre- and post-stenting, providing a framework for bifurcation stenting optimization and generating new hypotheses that can be tested clinically.

To date, several computational stent simulation studies have been reported, with the majority focusing on idealized non-bifurcated geometries6,7,8,9,10. Very few computational studies have focused on coronary bifurcations, mostly simulating one-stent techniques using simplified plaque material properties11,12. In this work, we aimed to present and validate a novel platform for fully computational, patient-specific coronary bifurcation stenting. Our computational simulation platform was trained in patient-specific bench bifurcation models and clinical cases. We blindly validated our platform in clinical cases. A variety of stent techniques and stent platforms were used.

Materials and methods

The study design of bench and clinical testing is summarized in the Online Figure 1.

Patient-specific bench stenting

Silicone bifurcation models

Four bench models of patient-specific coronary artery bifurcations were created using an in-house developed technique13. The initial bifurcation geometries were 3D reconstructed from human coronary angiograms (CAAS, Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands). For each model, a negative mold was designed, and 3D printed with acrylonitrile butadiene styrene material. After smoothing the inner surface of the mold using acetone vapor, polydimethylsiloxane (Sylgard 184, Dow Corning Corporation, Midland, MI, USA) was injected into the mold and then placed in an oven for curing of polydimethylsiloxane. The physical models were then immersed in an acetone beaker to dissolve the acrylonitrile butadiene styrene and generate the final silicone bifurcation models for bench testing.

Contrast enhanced micro-computed tomography (μCT) imaging

To acquire high-resolution lumen geometry, all silicone bifurcation models were filled with contrast and scanned with μCT (Bruker SkyScan 1172, Kontich, Belgium, https://www.bruker.com/ru/products-and-solutions/preclinical-imaging/micro-ct/skyscan-1272.html) using the following parameters: Image pixel size (26.9 μm), voltage (100 kV), and current (100 μA). The reconstructed 3D models based on μCT before stenting served as anatomical input to computational stent simulations13.

Bench stenting of silicone bifurcation models

The silicone bifurcation models were placed in a custom-made flow chamber13. A computer-controlled bioreactor circuit was connected to the inlet and outlet of the bifurcation and facilitated the circulation of 1 L of deionized water at a steady flow-rate of 100 mL/min. The stenting techniques performed on the silicone bifurcation models are summarized in Table 1.

Stereoscopic scanning

All the stents deployed in the silicone bifurcation models were imaged with a stereoscopic microscope (Olympus SZX16, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The microscopic images were used to measure the distance of the stent edges from fixed points (e.g. carina) and guide stent positioning in the computational models.

Computational simulation of bench bifurcation stenting

Computational mesh The 3D reconstructed lumens by μCT were meshed with four-node quadrilateral shell elements using HyperMesh (Altair Engineering, Troy, MI, USA). The stent design models used in bench stenting were provided by the manufacturers in their nominal dimensions. The balloons were computationally created in Grasshopper (plugin to Rhinoceros 6.0, Robert McNeel and Associates, Seattle, WA, USA) in their crimped state. The stents were meshed in HyperMesh using beam elements (Resolute Integrity and Onyx; Medtronic Vascular, Santa Rosa, CA, USA) or hexahedral elements (Synergy; Boston Scientific, Maple Groove, MN, USA), whereas the balloons were meshed with quadrilateral finite-membrane-strain elements.

Material properties The stent and silicone material properties used in the computational simulations of bench models are listed in Table 214. The cured silicone samples (“Silicone bifurcation models” section) were cut into rectangular specimens and underwent uni-axial compression testing. The obtained force–displacement curves were converted into stress–strain curves. The Neo-Hookean hyperelastic model was used to fit the non-linear stress–strain curve. A specific thickness was assigned to the shell elements of each bifurcation to represent the true thickness of the silicone models. The elastic modulus for compliant, semi- and non-compliant balloons was defined as 300 MPa, 900 MPa and 1500 MPa, respectively15.

Stent and balloon crimping, positioning, and bending The correct stent and balloon positioning in the computational bifurcation models was determined by angiography, μCT and stereoscopic imaging of the stented silicone models. The stents were first crimped from their nominal states using surface elements driven by radial displacement. Then, the crimped stents and balloons were positioned and bent along the artery centerline16.

Computational simulation of bench stenting procedures The bench stenting procedures were simulated through a multi-step, quasi-static finite element analysis using the central difference method (Abaqus/Explicit solver, Dassault Systèmes Simulia Corporation, Providence, RI, USA). The steps followed in the stenting procedures are summarized in Table 1. Only the edges of the bifurcation lumen were fixed to avoid rigid body motion. Balloon edges were constrained to eliminate motion in all directions. To model the interactions between different elements (balloon–stent, stent–lumen, balloon–lumen, balloon–balloon, stent–stent), the robust general contact algorithm was used with a friction coefficient of 0.217. The real inflation pressures used in each procedural step were applied to the inner surface of the corresponding balloons. The stressed configurations of lumen and stent after each step were used as the initial condition for the next step. Given the large number of elements and complicated contacts in the computational model, a computer cluster (452 Intel Xeon E5-2670 2.60 GHz 2 CPU/16 cores and 64 GB RAM per node, University of Nebraska, NE, USA) was used to perform the high-speed computational simulations.

Training of computational bench stenting

The 3D reconstructed bifurcation and stent geometry by μCT post-stenting served as the ground truth for the training of computational stenting. The simulated bifurcation and μCT bifurcation were co-registered using the bifurcation carina as the fixed point. The mean lumen diameter (MLD) was used for the comparison studies.

Clinical stenting

Patient data

Ten patient cases were selected for the patient-specific computational simulations from PROPOT (Randomized trial of the proximal optimization technique in coronary bifurcation lesions), a multi-center, prospective, open-label study that compared proximal optimization technique (POT) versus kissing balloon inflation (KBI) in provisional stenting of coronary bifurcations using Zotarolimus-eluting stents (Resolute Integrity or Onyx, Medtronic; Online Table 1). The use of these geometries was approved by the ethics committee of Teikyo University (IRB approval number #15-159-2). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

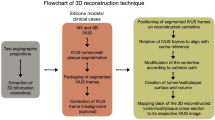

All patients of this study underwent coronary angiography (at multiple angiographic planes) and intracoronary imaging with optical coherence tomography (OCT) of main vessel (MV) and side branch (SB) before the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), immediately post stenting, and at the end of the procedure. Pre-PCI anatomical imaging data were used to 3D reconstruct the patient-specific coronary bifurcation anatomies which served as anatomical input to the computational stenting simulations13. The steps of computational simulations of clinical bifurcation stenting is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Workflow of patient-specific computational stenting simulations. Overview of the steps required for computational simulations of bifurcation stenting. The bifurcation lumen and wall are 3D reconstructed by fusing angiography and OCT (Steps 1 and 2). The 3D reconstructed model is meshed and assigned with patient-specific plaque material properties based on OCT imaging (Step 3). The real stent and balloon designs are computationally positioned in the bifurcation (Step 4). Using finite element method, the stenting procedure is computationally performed (Step 4). The output of the simulation includes stent morphometry and biomechanics (Step 5); IVUS intravascular ultrasound, OCT optical coherence tomography, SB side branch, MV main vessel, TAWSS time-averaged wall shear stress.

Training group Five out of ten cases (patient #1–5, Table 3) were used for training of the computational stenting platform, wherein none of the operators were blinded. All the PCI steps performed in this group of cases were replicated in the computational environment as described in “Computational simulation of clinical stenting” section. The post-PCI OCT data were used as the ground truth for the comparison to the computational simulations.

Testing group Five cases (patient #6–10, Table 3) were chosen for testing of the computational stenting platform. The operators responsible for angiography and OCT imaging analysis, 3D reconstruction of vessels, computational stenting simulations and comparison studies were blinded to each other. The stenting simulation results were compared with the post-PCI OCT data.

3D reconstruction of bifurcation geometry

The pre-PCI bifurcation geometries were 3D reconstructed from fusion of angiography with OCT13. The bifurcation centerline was generated from two angiographic planes (CAAS, Pie Medical Imaging BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands), and served as the backbone for the reconstruction. The segmented OCT images (EchoPlaque 4.0, INDEC Medical System, Los Altos, CA, USA) were aligned along the centerline using carina as reference point. We followed a systematic approach for the delineation of the outer borders in OCT images, as previously described13. In cases of ill-defined outer wall borders, our approach involved limiting the segmentation at the margin of complete signal loss. If the margin of complete signal loss could not be identified in < 180 degrees of vessel circumference, we interpolated with the visible border, but if it was unidentifiable in > 180 degrees of vessel circumference, we discarded that particular OCT frame. The aligned lumen and wall contours were lofted to build the MV and SB inner and outer surfaces. Then, the MV and SB surfaces were merged to create the bifurcation lumen and wall.

Computational simulation of clinical stenting

Computational mesh The 3D reconstructed bifurcation models were meshed with 0.25 mm hexahedral elements (ICEM CFD 17.2, ANSYS Inc., Canonsburg, PA, USA). Mesh convergence study using different element sizes (from 0.50 to 0.25 mm) showed minimal difference (< 1%) in stent expansion18. The stent design models were provided by the manufacturer (Medtronic Vascular) in their nominal dimensions. The balloons were constructed in Grasshopper in their crimped state. The stents and balloons were meshed using fully hexahedral and quadrilateral finite-membrane-strain elements, respectively.

Material properties In computational simulations, the wall thickness, lumen area, plaque eccentricity and plaque material were determined by OCT, as previously described18. A novel plaque scoring system was established based on the experimental data represented by the stress-strain graph of the constitutive equation with multiple coefficients (Online Figure 2)18,19. The area, circumference, and thickness of the lipid, fibrous, and calcified material were assessed in each OCT frame of MV and SB pullback by an imaging expert (YSC). Of note, the imaging expert was blind to the simulation results of the testing group. Then, the MV and SB were divided into sequential zones of heterogeneous plaque material and assigned with a quarter number (e.g. − 0.25, 0, + 0.25 etc.) ranging from + 2 (calcium only, very stiff) to − 2 (lipid only, very soft)18. The normal wall thickness and tapering were assessed by OCT. The normal wall material was modeled using the sixth-order reduced polynomial constitutive equation to characterize the isotropic hyper-elastic mechanical behavior, as previously described20. The material coefficients for normal arterial wall and plaque are listed in Table 2. The nickel cobalt alloy MP35N of Resolute Integrity and Onyx was modeled with the Von Mises-Hill plasticity model with isotropic hardening, while the Pt–Ir alloy core of Resolute Onyx was modeled with perfect plasticity. The material coefficients for the two alloys are listed in Table 2. The balloons were modeled as pure linear elastic materials with the same material properties as in simulations of the bench group.

Stent and balloon crimping, positioning, and bending All stents were first crimped from their nominal states using surface elements driven by radial displacement18. The crimped stents and balloons were positioned and bent along the centerline (Fig. 1). The stent and balloons were precisely positioned within the bifurcations with reference to fiduciary markers (i.e. radiopaque markers of stent/balloons, carina, and intersection points of guidewires) in angiography and OCT. Since the information on the exact location of side branch recrossing was not available, in the computational stenting simulations, we recrossed the side branch through distal struts.

Computational simulations All steps of the PCI procedures were computationally replicated through a multi-step, large-deformation, quasi-static finite element analysis using the central difference method (Abaqus/Explicit solver; Table 3)18. In all analyses, the duration of balloon inflation and deflation was set to 0.05 s and the target time increments were set as 5 × 10–8 s (adjusted via mass scaling) to obtain fast quasi-static results while avoiding dynamic effects. The boundary conditions, simulation parameters and computer cluster described above in “Computational simulation of bench bifurcation stenting” section was used to perform the computational simulations.

3D stent reconstruction from OCT

The stents were 3D reconstructed from OCT and angiographic images using a custom-built Grasshopper Python code21. First, the stent struts were segmented as individual points and flattened to 2D surfaces. Using the 2D stent design pattern as reference, the stent points were connected by lines that represented the centerlines of stent struts and links. Then, the 2D stent centerlines were wrapped and mapped back to the 3D lumen centerline, and finally, the volume of stent struts was added.

Computational fluid dynamic studies

The post-computational PCI bifurcation and stent geometries were used to discretize the fluid domain for CFD analyses (Fig. 1)21,22,23. The fluid domain was meshed with tetrahedral elements using ICEM CFD (ANSYS Inc.). Transient CFD simulations were performed with Fluent (ANSYS Inc.). Pulsatile flow was applied at the inlet of each artery24, and the inlet velocity was adjusted according to the inlet diameter25. To minimize the effect of boundary conditions, we added extensions (length = 10 times of the inlet diameter) to the inlet and outlet sections. The Huo-Kassab (HK) law26 was used to derive the relation between the diameter ratio of two daughter branches and the flow ratio through the branches. The lumen and stent surfaces were approximated as a rigid body, where non-slip boundary conditions were applied. The blood density was considered constant with a value of 1060 kg/m322. The Carreau model was adopted to consider the non-Newtonian nature of blood. The following values for each parameter were used27: \({\mu }_{\infty }=0.0035\,{\text{Pa}}\,{\text{s}}\), \({\mu }_{0}=0.25\,{\text{Pa}}\,{\text{s}}\), \(\lambda =25\,{\text{s}}\) and \(n=0.25\). Three full cardiac cycles were simulated, and the results of the last cycle were used28.

Comparison metrics

The final lumen and stent geometries after computational stenting simulations were compared to the lumen and stent cross-sections segmented on post-PCI OCT. The cross-sections from post-PCI OCT were used as reference. The simulated bifurcation and frame number of OCT cross-sections were co-registered using carina as the fixed marker. The MLD along the stented MV and the mean stent diameter (MSD) were used as comparison metrics.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed with the statistical package GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard error of mean. Bland–Altman analysis was used to measure agreement for method comparison studies.

Results

Bench simulations

All bench stenting procedures, the majority of which were multi-step two- stent techniques, were successfully simulated. Figure 2 illustrates a representative example of Culotte technique with two stents. Visually, the computationally simulated stents were nearly identical in size and shape to the actual μCT-reconstructed stents (Fig. 3a). The MLD was plotted along the axial direction of the simulated and μCT reconstructed stents (Fig. 3b), and quantitatively compared the agreement between methods with Bland–Altman analysis that yielded an overall mean difference of 0.03 (− 0.28 to 0.34) mm (Table 4).

Representative computational simulation of a bench stenting case. A patient-specific silicone bifurcation geometry was stented on the bench with the culotte technique. We faithfully replicated computationally all the steps of the stenting procedure using the same bifurcation geometry and stent/balloon designs; SB side branch, MV main vessel.

Computational stenting simulation versus µCT (Bench cases). Qualitative (a) and morphometric (b) comparison of computational stenting simulations against bench stenting imaged by μCT. Graphs show the stented part of the lumen only. Bias refers to the average difference in mean lumen diameters (MLD; 95% limits of agreement) between methods by Bland–Altman analysis; MV main vessel, SB side branch, µCT micro-computed tomography.

Contrast-enhanced μCT and stereoscopic images further revealed the ability of our computational stenting platform to replicate, with high precision, fine details of the bench stenting procedures, including malapposed struts, side branch ostium size and shape, and gaps in struts around the anatomically sensitive site of the carina (Fig. 4).

Qualitative comparison of computational stenting simulation of bench bifurcation models at the carina. Computational stenting (a) compared with bench stenting imaged by μCT (b) and stereoscopy (c) at the anatomically sensitive site of the carina. Simulation cross-sections (red) compared with the cross-sections from the µCT reconstructed model (black) showing similarity in the lumen shape at carina. In case #1 note the similarity of two stent links (black arrows), and the vessel curvature (black dotted line) in simulation and µCT and stereoscopic image. In case #2, note the similarity in vessel curvature (black dotted line). In case #3, note the very similar link position and shape (black dotted rectangle) at the bifurcation. In case #4, note the similarity in the position of stent link (black arrow); TAP T and protrusion, µCT micro-computed tomography.

Clinical simulations

Training group

In the training group, the clinical stenting procedures were successfully simulated with our computational platform. The one-stent technique was followed for all of these procedures. Online Figure 3 summarizes all the steps of a representative case (Patient #1), in which provisional stenting technique with POT was followed. The Online Video shows the procedural steps of the case of patient #5. Visually, the computationally stented bifurcation lumen yielded high qualitative agreement with the angiographic lumen post stenting (Online Figure 4). Bland–Altman analysis revealed MLD differences close to zero [mean bias 0.08 mm (− 0.24 to 0.41) mm; Table 5, Online Figure 5]. Similarly, the computationally simulated stents exhibited high similarity to the shape and size of the actual stents which were 3D reconstructed by fusing OCT and angiography (Online Figures 6a and 6b). The MSD of the computationally simulated stents was quantitatively compared to the OCT stent segmentations, yielding very high agreement [mean bias 0.13 mm (− 0.21 to 0.48) mm; Table 6, Online Figures 5 and 6c]. Notably, in Patient #1, the computational simulation replicated the stent under-expansion around the carina secondary to the local stiff plaque material. In Patient #5, the computational stenting reproduced the large gaps between stent struts and consequent over-dilated lumen at the proximal MV following the proximal stent post-dilatation.

Testing group

In the testing group, we used only the pre-procedural anatomical information (angiography and OCT) to assess the ability of our computational platform to replicate the clinical stenting (Fig. 5). The computational simulation operators were blinded to the post-procedural OCT. As shown in Figs. 6 and 7, computational stenting yielded very high agreement to post-procedural OCT suggesting the robustness of our platform. Quantitative comparisons by Bland–Altman analysis showed small differences in MLD and MSD [mean bias 0.08 mm (− 0.29 to 0.46) mm and 0.14 mm (− 0.25 to 0.54) mm, respectively; Tables 5 and 6, Online Figure 5]. Figure 8 shows a representative example of a blinded testing case. Pre-procedural OCT provided anatomical inputs (lumen area, plaque thickness, plaque eccentricity and plaque material properties) in our computational platform. Patient-specific computational stent simulations yielded similar lumen and stent expansion with the post-procedural OCT.

Representative computational stent simulation of a clinical case (Testing group). A patient-specific bifurcation geometry was stented clinically following the provisional technique. We faithfully replicated computationally all the steps of the stenting procedure using the same bifurcation anatomy, wall material properties, stent/balloon designs, inflation pressure and stenting technique. Note that the computational simulation was blinded to the post-procedural OCT. Material properties were assigned to the 3D reconstructed bifurcation wall based on OCT imaging (Vessel in top left). Wall stiffness score varied from − 0.25 (Fibrolipid material) to + 0.50 (Fibrocalcific material); MV main vessel, SB side branch.

Blind comparison of computational stenting simulation versus angiography and OCT (Testing group). Qualitative (a, b), and quantitative (c) comparison of lumen size after computational stenting against angiography and OCT imaging. The graphs include the stented part of the lumen. Note that the computational stent simulation was blind to the final OCT results post-procedure; MV main vessel, SB side branch, MLD mean lumen diameter.

Blind computational stenting simulation versus OCT (Testing group). Qualitative (a, b), and quantitative (c) comparison of mean stent diameter (MSD) after computational stenting against OCT. The stents in (b) were 3D reconstructed from OCT21. Note that the computational stent simulation was blind to the final OCT results post-procedure.

Representative example showing the similarity between computational stenting simulation and reality (OCT). Left column shows the lumen size pre-stenting and right column shows the lumen size post-stenting. The figure illustrates the pre-procedural 3D reconstructed vessel anatomy and plaque stiffness, as well as the post-procedural stented vessel. Note the similarity in pre-stenting lumen size, shape and plaque constituents by OCT versus computational simulation. In the computational simulation, this vessel cross-section was assigned + 0.50 plaque stiffness based on OCT imaging. Likewise, note the similarity in post-stenting lumen size and shape, as well as stent size and circumferential configuration by OCT and computational simulation; FL fibrolipid.

Processing times

The average processing times from model preparation to completion of the computational simulations are provided in Table 7.

CFD studies

To show the feasibility of CFD in our simulated procedures, we compared the time-averaged wall shear stress (TAWSS) along the axial direction of MV and SB before and after computational stenting (Online Figure 7). As shown quantitatively and qualitatively, stenting smoothed the wall shear stress pattern along the MV, resulting in lower time averaged wall shear stress at the stenosis.

Discussion

In this work, we presented and validated a novel, fully computational methodology for patient-specific stenting simulations of coronary artery bifurcations. Our computational simulation platform was trained using patient-specific bench and clinical cases, covering a wide spectrum of bifurcation disease complexity, stenting techniques (1- and 2-stent techniques), and drug-eluting stent platforms (zotarolimus- and everolimus-eluting stents). The accuracy of our platform was tested blindly against clinical cases. High resolution imaging of bench and clinical cases with μCT and OCT, respectively, was used as the ground truth for the training and testing of computational stenting. Collectively, our studies demonstrate that computational bifurcation stenting is feasible and accurate. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to present and validate a full pipeline from bifurcation imaging to computational 3D reconstruction, computational stent deployment (using realistic plaque properties), and CFD analysis. Furthermore, this is the first study in which multiple stenting techniques and stent platforms were simulated in patient-specific bifurcation geometries. Previous attempts to virtually implant stents in patient-specific bifurcation models had several limitations (simplified 1-stent technique, inaccurate representation of true bifurcation anatomy and plaque material properties, and lack of blinded validation)11,20.

Of note, the ability of our computational stenting platform to perform realistic stent simulations was exhibited in clinical cases, in which the operators of computational simulations were blinded to post-procedural imaging. The feasibility and robustness of our platform was based on two important features: (i) Precise anatomical representation of the bifurcation, and (ii) Assignment of realistic plaque anatomy and material properties. We used either μCT or OCT for the anatomical representation of bifurcation, paying attention to the accurate reconstruction of the anatomically sensitive region of carina. Other imaging modalities, including intravascular ultrasound or coronary computed tomography angiography could also perform well with our platform. Unlike previous studies, we employed a sophisticated approach to achieve realistic vessel response to stent and balloon expansion by integrating the following plaque morphology components: (i) Pre-procedural lumen stenosis, (ii) Plaque thickness, (iii) Plaque eccentricity, and (iv) Plaque tissue characteristics.

Another key feature of our computational stenting platform is the versatility across different stenting techniques and stent platforms/sizes. In the patient-specific bench models, our computational approach accurately replicated all the steps of almost all the guideline-proposed bifurcation stenting techniques29, i.e. provisional, T-and-protrusion and culotte followed by POT and KBI (detailed steps are shown in Table 1). In the clinical cases, we performed provisional stenting followed by KBI or POT (detailed steps are shown in Table 3). In all these computational simulations, different stent platforms were used, including the laser-cut everolimus-eluting stents, wire stent with circular strut cross-section (Resolute Integrity), and wire stent with shell-core strut cross-section (Resolute Onyx). Overall, our computational simulations (particularly the 2-stent techniques) involved multiple complicated contacts, i.e. balloon-stent, balloon-artery, stent-artery, stent-stent, balloon-balloon, and multiple steps with each step serving as input for the next one. These non-linear contacts could create computational and geometrical errors multiplied and propagated throughout the steps if they were not handled correctly. The incorporation of accurate bifurcation anatomy and plaque morphology were fundamental for the successful completion of our multi-step, quasi-static, finite element analyses and one of the major novelties in this work. Notably, we replicated the correct stent position not only in the longitudinal direction, but also in the circumferential direction. This is of paramount clinical importance when it comes to jailing of SB ostium (Fig. 4).

Clinical perspectives

The proposed computational platform for patient-specific bifurcation stenting simulations provides a reliable resource for clinical research, clinical decision making, stent manufacturing and education on stenting techniques. Computational stenting can be used in virtual (in-silico) clinical trials using patient-specific anatomical and physiological data and provide surrogate endpoints (i.e. under-expansion, malapposition, flow dynamics) that are highly predictive of clinical endpoints. These virtual clinical trials can be adequately powered with large volume patient data to investigate the performance of different stenting techniques or stent platforms, thereby guiding the actual clinical trials. Flow ISR study, which is currently underway, is an example of such a virtual clinical trial. The study compares different 1- and 2-stent techniques in patient-specific coronary bifurcations. In cardiac catheterization laboratory, computational stenting simulations can be used for pre-procedural planning and decision-making. Computational simulation assisted identification of the optimal stent strategy can provide invaluable guidance to the interventionalist to increase the procedural success and achieve favorable long-term clinical outcomes. When it comes to stent manufacturers, a cost- and time-effective computational stenting strategy using patient-specific anatomies has the potential to reduce the need for bench and animal research for stent testing. Computational simulations can help with stent design optimization (e.g. number of crowns and links, strut size) and mechanics (radial and longitudinal strength, expansion capability, vessel scaffolding)18. The computational approach can effectively evaluate different stent designs in realistic vessel environments obviating the need to manufacture and experimentally test stent prototypes, ultimately reducing the development time and manufacturing costs. Another important consideration with computational stenting is that it can be used as an educational tool to train healthcare providers on bifurcation stenting techniques. Extended reality technologies can further assist towards this direction. Finally, computational bifurcation stenting can be translated to other vascular beds (e.g. carotid, renal or aortic bifurcations) and structural heart interventions.

Limitations

There are several limitations within our study. First, in simulations of clinical cases the vessel motion related to cardiac cycle was not considered. Adding the parameter of time (4D simulation) would potentially make the simulation more realistic, at the expense of increased computational time. The tradeoff between improved accuracy and increased computational time warrants further investigation. Second, in rare cases with very tortuous or complex coronary geometries that are not clearly visualized on two angiographic views (at least 30 degrees apart), 3D reconstruction of the bifurcation and consequently computational stenting simulation might be limited. Third, in the clinical cases, plaque was 3D reconstructed by OCT. We acknowledge that OCT is not the best modality to visualize the outer vessel; however, in the majority of OCT frames we were able to identify the outer plaque borders with confidence. Fourth, the processing time was about 7.0 ± 1.5 h per simulation step (Table 7). One of our priorities is to reduce the processing time by streamlining our computational methods and increasing the computer power and integrating machine learning techniques. Fifth, we made some assumptions in the simulations of bench cases: To avoid heavy computational load in the bench simulations, the silicone wall was meshed with shell elements. Since the silicone wall thickness varied in each model, the assigned shell thickness could deviate slightly from the real silicone wall thickness. However, no significant errors were expected from this assumption. The material properties of silicone were obtained by fitting the stress–strain curve from compression tests, which may differ than that derived from the tensile tests. Sixth, there were some technical assumptions in the simulations of clinical cases. The material properties of different plaque types were adopted from literature19. However, the literature data are quite representative of the entire spectrum of plaque material properties and we feel that they did not deviate from the true plaque properties. In accordance with previous studies17,30, we used the idealized multi-wing crimped balloon model. We adopted the material properties for compliant, semi-compliant and non-compliant balloons from literature15. The computational model could be improved if the material properties of the balloon were calibrated to the corresponding compliance data from the manufacturer31. The pre-stressed state of the arterial wall due to blood pressure was neglected. Finally, the primary purpose of this work was to virtually replicate the actual stenting steps. The reverse process of executing the computational simulation steps in the cardiac catheterization laboratory is a fascinating perspective that warrants to be tested in future work.

Conclusions

Patient-specific computational stenting of coronary artery bifurcations is a feasible and accurate approach. Future studies are warranted to investigate the ability of computational stenting simulations to guide decision making in the cardiac catheterization laboratory and improve clinical outcomes.

Abbreviations

- 2D:

-

Two-dimensional

- 3D:

-

Three-dimensional

- CFD:

-

Computational fluid dynamics

- IQR:

-

Inter quartile range

- KBI:

-

Kissing balloon inflation

- MLA:

-

Mean lumen area

- MLD:

-

Mean lumen diameter

- MSD:

-

Mean stent diameter

- MV:

-

Main vessel

- NC:

-

Non-compliant

- OCT:

-

Optical coherence tomography

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- POT:

-

Proximal optimization technique

- SB:

-

Side branch

- SC:

-

Semi-compliant

- TAWSS:

-

Time-averaged wall shear stress

- μCT:

-

Micro-computed tomography

References

Antoniadis, A. P. et al. Biomechanical modeling to improve coronary artery bifurcation stenting: Expert review document on techniques and clinical implementation. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 8, 1281–1296 (2015).

Burzotta, F. et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention for bifurcation coronary lesions: The 15(th) consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 16, 1307–1317 (2021).

Colombo, A. et al. Randomized study to evaluate sirolimus-eluting stents implanted at coronary bifurcation lesions. Circulation 109, 1244–1249 (2004).

Mortier, P. et al. A novel simulation strategy for stent insertion and deployment in curved coronary bifurcations: Comparison of three drug-eluting stents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 88–99 (2010).

Mortier, P. et al. Provisional stenting of coronary bifurcations: insights into final kissing balloon post-dilation and stent design by computational modeling. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 7, 325–333 (2014).

Zhao, S., Gu, L. & Froemming, S. R. On the importance of modeling stent procedure for predicting arterial mechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 121005 (2012).

Conway, C., Sharif, F., McGarry, J. P. & McHugh, P. E. A computational test-bed to assess coronary stent implantation mechanics using a population-specific approach. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 3, 374–387 (2012).

Mortier, P. D. B. M., Segers, P., Verdonck, P. & Verhegghe, B. Virtual bench testing of new generation coronary stents. Eurointerventions 7, 369–376 (2011).

Wu, W. et al. Finite element shape optimization for biodegradable magnesium alloy stents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 38, 2829–2840 (2010).

Gijsen, F. J. H. et al. Simulation of stent deployment in a realistic human coronary artery. Biomed. Eng. Online 7, 23 (2008).

Morlacchi, S. et al. Patient-specific simulations of stenting procedures in coronary bifurcations: Two clinical cases. Med. Eng. Phys. 35, 1272–1281 (2013).

Peter, M. et al. Patient-specific computer modelling of coronary bifurcation stenting: The John Doe programme. EuroIntervention 11, 35–39 (2015).

Wu, W. et al. 3D reconstruction of coronary artery bifurcations from coronary angiography and optical coherence tomography: Feasibility, validation, and reproducibility. Sci. Rep. 10, 18049 (2020).

O’Brien, B. J., Stinson, J. S., Larsen, S. R., Eppihimer, M. J. & Carroll, W. M. A platinum–chromium steel for cardiovascular stents. Biomaterials 31, 3755–3761 (2010).

Xu, J., Yang, J., Sohrabi, S., Zhou, Y. & Liu, Y. Finite element analysis of the implantation process of overlapping stents. J. Med. Device 11, 0210101–0210109 (2017).

Iannaccone, F. et al. Impact of plaque type and side branch geometry on side branch compromise after provisional stent implantation: A simulation study. EuroIntervention 13, e236–e245 (2017).

Grundeken, M. J. et al. Differences in rotational positioning and subsequent distal main branch rewiring of the Tryton stent: An optical coherence tomography and computational study. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 92, 897–906 (2018).

Samant, S. et al. Computational and experimental mechanical performance of a new everolimus-eluting stent purpose-built for left main interventions. Sci. Rep. 11, 8728 (2021).

Loree, H. M., Grodzinsky, A. J., Park, S. Y., Gibson, L. J. & Lee, R. T. Static circumferential tangential modulus of human atherosclerotic tissue. J. Biomech. 27, 195–204 (1994).

Chiastra, C. et al. Computational replication of the patient-specific stenting procedure for coronary artery bifurcations: From OCT and CT imaging to structural and hemodynamics analyses. J. Biomech. 49, 2102–2111 (2016).

Wu, W. et al. 3D Reconstruction of coronary artery stents from optical coherence tomography: Experimental validation and clinical feasibility. Sci. Rep. 11, 12252 (2021).

Chiastra, C. et al. Computational fluid dynamic simulations of image-based stented coronary bifurcation models. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130193 (2013).

Morlacchi, S. et al. Sequential structural and fluid dynamic numerical simulations of a stented bifurcated coronary artery. J. Biomech. Eng. 133, 121010 (2011).

Davies, J. E. et al. Evidence of a dominant backward-propagating “suction” wave responsible for diastolic coronary filling in humans, attenuated in left ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 113, 1768–1778 (2006).

van der Giessen, A. G. et al. The influence of boundary conditions on wall shear stress distribution in patients specific coronary trees. J. Biomech. 44, 1089–1095 (2011).

Huo, Y. et al. Which diameter and angle rule provides optimal flow patterns in a coronary bifurcation?. J. Biomech. 45, 1273–1279 (2012).

Seo, T., Schachter, L. G. & Barakat, A. I. Computational study of fluid mechanical disturbance induced by endovascular stents. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 33, 444–456 (2005).

Chiastra, C., Morlacchi, S., Pereira, S., Dubini, G. & Migliavacca, F. Computational fluid dynamics of stented coronary bifurcations studied with a hybrid discretization method. Eur. J. Mech. B. Fluids 35, 76–84 (2012).

Ormiston, J. A. et al. Bench testing and coronary artery bifurcations: A consensus document from the European Bifurcation Club. EuroIntervention 13, e1794–e1803 (2018).

Chiastra, C. et al. Biomechanical impact of wrong positioning of a dedicated stent for coronary bifurcations: A virtual bench testing study. Cardiovasc. Eng. Technol. 9, 415–426 (2018).

Morris, P. D. et al. Simultaneous kissing stents to treat unprotected left main stem coronary artery bifurcation disease; stent expansion, vessel injury, hemodynamics, tissue healing, restenosis, and repeat revascularization. Catheter. Cardiovasc. Interv. 92, E381–E392 (2018).

Schievano, S. et al. Finite element analysis of stent deployment: Understanding stent fracture in percutaneous pulmonary valve implantation. J. Interv. Cardiol. 20, 546–554 (2007).

Funding

National Institutes of Health (R01 HL144690-01); Dr. Vincent Miscia Cardiovascular Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.S.C., W.W., and S.Z., conceived and designed study, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the manuscript, revised critically for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript submitted. S.S., B.K., J.M., M.S., D.Z., A.P., G.S.K., Y.W., and Y.M. analyzed and interpreted the data, revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the manuscript submitted. F.B., F.M., T.W.J., T.L., J.F.L., E.S.B., D.L.B., G.D., C.C., G.S., and Y.L., revised the manuscript critically for intellectual content and approved the manuscript submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Yiannis S. Chatzizisis: Speaker honoraria, advisory board fees and research grant from Boston Scientific Inc.; Advisory board fees and research grant from Medtronic Inc.; Issued U.S. patent (No. 11,026,749) and international patent pending (application No. PCT/US2020/057304) for the invention entitled “Computational simulation platform for the planning of interventional procedures”; Co-founder of ComKardia Inc. Emmanouil S. Brilakis: Consulting/Speaker honoraria from Abbott Vascular, American Heart Association (associate editor Circulation), Amgen, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Cardiovascular Innovations Foundation (Board of Directors), CSI, Elsevier, GE Healthcare, InfraRedx, Medtronic, Siemens, and Teleflex; Research support from Regeneron and Siemens: Shareholder in MHI Ventures. Francesco Burzotta: Speaker honoraria from Medtronic, Abbott and Abiomed. Deepak L. Bhatt: Advisory Board: Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Elsevier Practice Update Cardiology, Janssen, Level Ex, Medscape Cardiology, MyoKardia, Novo Nordisk, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regado Biosciences; Board of Directors: Boston VA Research Institute, Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care, TobeSoft; Chair: American Heart Association Quality Oversight Committee; Data Monitoring Committees: Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute, for the PORTICO trial, funded by St. Jude Medical, now Abbott), Cleveland Clinic (including for the ExCEED trial, funded by Edwards), Contego Medical (Chair, PERFORMANCE 2), Duke Clinical Research Institute, Mayo Clinic, Mount Sinai School of Medicine (for the ENVISAGE trial, funded by Daiichi Sankyo), Population Health Research Institute; Honoraria: American College of Cardiology (Senior Associate Editor, Clinical Trials and News, ACC.org; Chair, ACC Accreditation Committee), Baim Institute for Clinical Research (formerly Harvard Clinical Research Institute; RE-DUAL PCI clinical trial steering committee funded by Boehringer Ingelheim; AEGIS-II executive committee funded by CSL Behring), Belvoir Publications (Editor in Chief, Harvard Heart Letter), Canadian Medical and Surgical Knowledge Translation Research Group (clinical trial steering committees), Duke Clinical Research Institute (clinical trial steering committees, including for the PRONOUNCE trial, funded by Ferring Pharmaceuticals), HMP Global (Editor in Chief, Journal of Invasive Cardiology), Journal of the American College of Cardiology (Guest Editor; Associate Editor), K2P (Co-Chair, interdisciplinary curriculum), Level Ex, Medtelligence/ReachMD (CME steering committees), MJH Life Sciences, Population Health Research Institute (for the COMPASS operations committee, publications committee, steering committee, and USA national co-leader, funded by Bayer), Slack Publications (Chief Medical Editor, Cardiology Today’s Intervention), Society of Cardiovascular Patient Care (Secretary/Treasurer), WebMD (CME steering committees); Other: Clinical Cardiology (Deputy Editor), NCDR-ACTION Registry Steering Committee (Chair), VA CART Research and Publications Committee (Chair); Research Funding: Abbott, Afimmune, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cardax, CellProthera, Cereno Scientific, Chiesi, CSL Behring, Eisai, Ethicon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Forest Laboratories, Fractyl, Garmin, HLS Therapeutics, Idorsia, Ironwood, Ischemix, Janssen, Lexicon, Lilly, Medtronic, MyoKardia, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Owkin, Pfizer, PhaseBio, PLx Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi, Synaptic, The Medicines Company, 89Bio; Royalties: Elsevier (Editor, Cardiovascular Intervention: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease); Site Co-Investigator: Abbott, Biotronik, Boston Scientific, CSI, St. Jude Medical (now Abbott), Svelte; Trustee: American College of Cardiology; Unfunded Research: FlowCo, Merck, Takeda. Thomas Johnson: Speaker/consultancy fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Terumo, and Vascular Perspectives. Research grants from AstraZeneca and Bayer. Thierry Lefèvre: Speaker/consultancy fees from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, and Terumo. All other authors have no relevant conflict of interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, S., Wu, W., Samant, S. et al. Patient-specific computational simulation of coronary artery bifurcation stenting. Sci Rep 11, 16486 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95026-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-95026-2

This article is cited by

-

Post-procedure micro-CT analyses of coronary artery stenting in left main vessels of reanimated and perfusion-fixed human hearts

BioMedical Engineering OnLine (2023)

-

Blood flow modeling reveals improved collateral artery performance during the regenerative period in mammalian hearts

Nature Cardiovascular Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.