Abstract

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) represent potential biomarkers because of their highly stable structure and robust expression pattern in clinical samples. The aim of this study was to evaluate the expression of a recently identified circRNA, hsa_circ_0005986; determine its clinical significance; and evaluate its potential as a biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). We evaluated hsa_circ_0005986 expression in 123 HCC tissue samples, its clinical significance, and its association with patients’ clinicopathological characteristics and survival. Hsa_circ_0005986 expression was downregulated in HCC tissues. Low hsa_circ_0005986 expression was more common in tumors larger than 5 cm [odds ratio (OR), 3.19; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.51–6.76; p = 0.002], advanced TNM stage (III/IV; OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.16–4.95; p = 0.018), and higher BCLC stage (B/C; OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.30–5.65; p = 0.007). High hsa_circ_0005986 expression was associated with improved survival and was an independent prognostic factor for overall [hazard ratio (HR), 0.572; 95% CI, 0.339–0.966; p = 0.037] and progression-free (HR, 0.573; 95% CI, 0.362–0.906; p = 0.017) survival. Moreover, the circRNA–miRNA–mRNA network was constructed using RNA-seq/miRNA-seq data and clinical information from TCGA-LIHC dataset. Our findings indicate a promising role for hsa_circ_0005986 as a prognostic biomarker in patients with HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer remains a public health concern worldwide. It represents a major economic and social burden as well as a significant cause of mortality1. In 2012, there were an estimated 14 million and 8 million new cancer cases and cancer-related deaths, respectively. This increased to more than 18 million and 9 million, respectively, in 2018, which is evidence of the rapidly increasing rates of cancer incidence and mortality2,3. In particular, liver cancer is a commonly diagnosed cancer worldwide and is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related mortality. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) accounts for approximately 80% of primary liver cancers2 and is associated with poor patient prognosis. HCC originates primarily in chronically damaged liver (i.e., liver cirrhosis resulting from chronic viral hepatitis B or C or long-term alcohol consumption). Frequent recurrence of HCC limits treatment options because of the underlying liver disease and impaired liver function.

Because of the poor prognosis associated with HCC, the identification of biomarkers is essential for predicting patient prognosis and survival and tumor recurrence as well as for determining suitable treatment options. The recent development of high-throughput sequencing techniques and advances in bioinformatics has resulted in an increase in the number of candidate biomarkers4. Noncoding RNAs such as long noncoding RNAs, microRNAs (miRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs) are some potential biomarkers that may have relevance to HCC.

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are a class of highly stable, single-stranded RNAs that form a loop through covalent binding. They are synthesized either from coding or noncoding genomic regions. Whereas circRNAs are formally known to be noncoding, recent evidence indicates the existence of protein-coding circRNAs5. In contrast to linear RNAs, circRNAs are formed through a back-splicing event, which occurs via the linkage of downstream 3′ and upstream 5′ splice sites to form covalent and canonical bonds6. Exons, introns, or both may serve as substrates for circRNA back-splicing. This produces four types of circRNAs: exonic (EcircRNAs), circular intronic (ciRNAs), exon–intron (EIciRNAs), and tRNA intronic (tricRNAs)7,8,9. Most circRNAs are EcircRNAs. ciRNAs are localized abundantly in the nucleus and show minute enrichment for target miRNA sites. Importantly, the fact that ciRNA knockdown can lead to the downregulation of the expression of its corresponding parental gene suggests that ciRNAs are involved in positively modulating transcription catalyzed by RNA polymerase II9. EIciRNAs are RNA molecules in which the exons are separated by retained introns. The nuclear abundance of both ciRNAs and EIciRNAs suggests that they are involved in transcriptional and post-transcriptional events7,8,10,11. Pre-tRNA splicing into two parts by specific enzymes gives rise to tRNA and tricRNA—a unique class of ciRNA12.

CircRNAs are present predominantly in the cytoplasm. They contain miRNA response elements (MREs) and serve as sponges for miRNAs, thereby downregulating their expression. This results in decreased miRNA-mediated mRNA degradation or translational repression.

Although the exact function of circRNAs remains unclear, many studies have revealed their involvement in both physiological and pathological processes13, including cell aging14, tissue development15,16, and neurological disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease17. Furthermore, circRNAs are expressed in various cancers, including glioblastoma multiforme18, colorectal19,20, breast21,22, gastric23, and bladder24 cancers as well as HCC25,26. circRNAs may serve as miRNA sponges27 and may be involved in epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT)28 and development29 of various cancers. Collectively, these findings indicate that circRNAs play important roles in various cellular processes and may serve as clinical biomarkers.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the expression of a recently identified circRNA, hsa_circ_0005986, determine its clinical significance, and evaluate its potential as a biomarker for HCC.

Materials and methods

Patients and tissue samples

This study included 162 patients with HCC (Fig. 1) who underwent diagnostic biopsy or surgical resection at Kyungpook National University Hospital, Republic of Korea, between March 2015 and August 2016. Thirty patients who had been previously treated for HCC and nine patients who were lost to follow-up were excluded from the study, resulting in a final sample size of 123 evaluable patients. Tissue samples were obtained by liver biopsy or surgical resection. Liver biopsy was performed to confirm HCC diagnosis and to rule out the presence of other tumors. Patients underwent surgical resection (n = 19) or radiofrequency ablation (n = 47) as curative treatment (n = 66, 53.7%) or transarterial chemoembolization (n = 9), sorafenib (n = 12) or best supportive care (n = 36) as non-curative treatment. This study was conducted according to local ethical guidelines, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

MRI image of a patient with cancer. Gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced liver MRI images of a patient with HCC. (A) A huge mass replacing the right lobe of the liver in the arterial phase. (B) The mass (arrowhead) and portal vein thrombosis (arrow) are more prominent in the portal phase. (C) The mass shows washout in the venous phase.

For post-treatment monitoring, imaging was conducted every 3–6 months using contrast-enhanced dynamic computed tomography (CT) or gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced liver magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). We defined overall survival as the time between the date of initial HCC diagnosis and either the date of death from any cause or the date of last contact with the patient during follow-up examination. Progression-free survival was defined as the time between the initial date of HCC diagnosis and either the first event of recurrence or progression or until death from any cause. The recurrence of HCC was recognized if a tumor exceeded 1 cm and showed characteristic CT or MRI contrast enhancement in the arterial phase and washout in the venous or delayed phase. Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (version 1.1) was used to evaluate tumor response. HCC specimens and adjacent non-tumor tissue specimens were immediately stored at 4 °C for 24 h in RNAlater reagent (Ambion; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and then stored at − 80 °C. We recorded the patients’ age and sex, number and size of tumor, presence of macrovascular invasion, tumor node metastasis (TNM) stage, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) stage, Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) category of liver function, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level, and other pertinent laboratory data. Cancer staging was performed according to the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (8th edition) and also following BCLC staging criteria. The ethical committee of our institution (Kyungpook National University Hospital) approved the study (#KNUH-2014-04-056-001), and all patients provided written informed consent prior to sample collection.

Total RNAs extraction and cDNA synthesis

QIAzol Lysis Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract total RNAs from the frozen specimens according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We used a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) to determine RNA concentration as well as its purity. A High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) was used to reverse transcribe cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

We used SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) to perform qRT-PCR. The expression of hsa_circ_0005986 was normalized to that of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and then quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method. All primers were synthesized by Bionics (Seoul, Korea). In order to amplify only hsa_circ_0005986, but not linear form of RNA, the primers were designed by considering the backsplice junctions of circRNA (Supplementary Fig. 1). The following primer sequences were used: 5′-GAA ACT GGC TGC GAT ATG TG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAC AGG CTC AGT AGT GTT CTT TAA A-3′ (reverse) for hsa_circ_0005986 and 5′-GGA AGG TGA AGG TCG GAG TC-3′ (forward) and 5'-GTT GAG GTC AAT GAA GGG GTC-3' (reverse) for GAPDH. qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate, and specific target amplification was confirmed by melting curve analysis.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive statistics, categorical data were expressed as number (%) and numerical data as the mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data and as the median with interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. A paired t-test was used to analyse differences in hsa_circ_0005986 expression between HCC and adjacent non-tumor tissue. We used the chi-square or Fisher’s exact probability test to compare clinicopathological characteristics between two groups with different hsa_circ_0005986 expressions. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to generate survival curves, and the log-rank test was conducted to compare survival curves between groups. The prognostic performances30 of hsa_circ_0005986 were expressed as specificity, sensitivity, and area under the receiver operating curve (AUC). To determine the predictors of survivals, univariate and multivariate analyses based on a Cox proportional hazards model were performed. p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Values that were statistically significant in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses, with a p-value of < 0.1. We conducted all the analyses using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and GraphPad Prism 6 program for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to generate figures.

Construction of the circRNA–miRNA–mRNA network31,32

Publicly available sequencing data (RNA-seq, miRNA-seq and clinical information data) related to HCC were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) using gdc-rnaseq-tool (https://github.com/cpreid2/gdc-rnaseq-tool). Differentially expressed genes and miRNA (|log2-fold change|≥ 1 and adjust p value < 0.05) were analyzed using the DEseq233 R package (version 1.30.1) for further analysis. A co-expression network was constructed using a WGCNA package34 (version 1.70-3) in the R software (version 4.0.3). Potential target miRNAs of hsa_circ_0005986 were predicted via circBank35. The overlapping part of the target miRNAs from co-expressed miRNAs from WGCNA were selected. The potential target genes of the selected miRNA were predicted using mirDB36. The overlapping part of the target genes from co-expressed genes from WGCNA were selected. The circRNA–miRNA–mRNA network was visualized using Cytoscape (version 3.8.2 for Mac).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical committee of our institution (Kyungpook National University Hospital) approved the study (#KNUH-2014-04-056-001), and all patients provided written informed consent prior to sample collection.

Consent for publication

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all participants.

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with HCC

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients with HCC. The patients predominantly comprised males (85.4%), and the mean age was 60.3 years. Liver disease was primarily caused by hepatitis B (61.0%), alcohol consumption (25.2%), hepatitis C (8.9%), or hepatitis B and C virus co-infection (1.6%). Sixty-five (52.8%) patients presented with a single tumor and 58 (47.2%) had multiple tumors. The tumor size was > 5 cm in 66 (53.7%) patients and ≤ 5 cm in 57 (46.3%) patients. Vessel invasion was observed in 44 (35.8%) patients. Overall, 66 (53.7%) patients had TNM stage I or II tumor and 57 (46.4%) had TNM stage III or IV tumor. Moreover, 59 (48.0%) patients had cancer at BCLC stages 0 and A and 64 (52.0%) patients had cancer at BCLC stages B and C. The CTP class was A in 105 (85.4%) patients and B in 18 (14.6%) patients. The median aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, bilirubin, albumin, and AFP levels and prothrombin time were 52.0 U/L, 37.0 U/L, 0.8 mg/dL, 3.9 g/dL, 52.8 ng/mL, and 12.6 s, respectively. Of these clinical characteristics, sex and etiology of liver disease were not statistically different between the curative treatment and non-curative treatment groups.

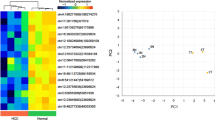

Downregulation of hsa_circ_0005986 expression in HCC tissues and advanced HCC

We found that the expression of hsa_circ_0005986 was significantly downregulated in HCC tissues compared with that in adjacent non-tumor tissues (Fig. 2). In addition, we found that the expression of hsa_circ_0005986 in TNM stages III and IV was significantly lower than that in stages I and II. Similarly, lower hsa_circ_0005986 expression was observed in BCLC stages B and C compared with that in stages 0 and A (Fig. 3).

Correlation between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and clinicopathological characteristics of patients with HCC

Table 2 shows the differences in patients’ characteristics based on the expression level of hsa_circ_0005986. Based on hsa_circ_0005986 expression, all patients were classified into a high-expression (≥ 0.0004347) or low-expression (< 0.0004347) group. The cutoff value was selected as the optimal value from the area under the curve (AUC) analysis of the time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve that maximized the sum of the specificity and sensitivity for predicting survival. Low hsa_circ_0005986 expression was associated with tumors larger than 5 cm [odds ratio (OR), 3.19; 95% confidence interval (CI), 1.51–6.76; p = 0.002), advanced TNM stage (III/IV; OR, 2.39; 95% CI, 1.16–4.95; p = 0.018), and higher BCLC stage (B/C; OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.30–5.65; p = 0.007).

Correlation between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and survival of patients with HCC

The overall survival of patients was significantly different according to hsa_circ_0005986 expression (Fig. 4A). The cumulative 1-, 2-, and 3-year overall survival rates were 45.5%, 38.2%, and 34.5%, respectively, in the low-expression group and 67.6%, 61.8%, and 56.6%, respectively, in the high-expression group.

The AUC of hsa_circ_0005986 for predicting survival was 0.633 (95% CI: 0.542–0.718, p = 0.009) with a sensitivity of 54.7% and specificity of 71.2%. The AUC of hsa_circ_0005986 for predicting progression was 0.673 (95% CI: 0.582–0.754, p = 0.001) with a sensitivity of 53.7% and specificity of 80.5%.

The univariate analysis of prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with HCC (Table 3) demonstrated the following significant predictors for overall survival: high hsa_circ_0005986 expression [hazard ratio (HR), 0.504; 95% CI, 0.307–0.828; p = 0.007], multiple tumors (HR, 3.655; 95% CI, 2.171–6.152; p < 0.001), large tumors (> 5 cm; HR, 10.083; 95% CI, 5.083–20.000; p < 0.001), vessel invasion (HR, 10.521; 95% CI, 5.983–18.502; p < 0.001), AFP level > 400 ng/mL (HR, 5.108; 95% CI, 3.077–8.481; p < 0.001), poor CTP class (HR, 3.283; 95% CI, 1.829–5.892; p < 0.001), and curative treatment (HR, 0.089; 95% CI, 0.048–0.167; p < 0.001).

Multivariate analysis identified the following independent prognostic factors for overall survival: high hsa_circ_0005986 expression (HR, 0.572; 95% CI, 0.339–0.966; p = 0.037), vessel invasion (HR, 3.364; 95% CI, 1.678–6.746; p = 0.001), AFP level > 400 ng/mL (HR, 1.846; 95% CI, 1.041–3.273; p = 0.036), and curative treatment (HR, 0.383; 95% CI, 0.158–0.929; p = 0.034).

Correlation between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and progression-free survival in patients with HCC

Progression-free survival differed significantly between patients depending on the hsa_circ_0005986 expression level (Fig. 4B). The cumulative 1-, 2-, and 3-year progression-free survival rates were 36.8%, 19.4%, and 14.8%, respectively, in the low-expression group and 61.8%, 43.1%, and 35.8%, respectively, in the high-expression group.

Univariate analysis of the factors associated with progression-free survival (Table 4) revealed the following significant prognostic factors: high hsa_circ_0005986 expression (HR, 0.492; 95% CI, 0.317–0.763; p = 0.002), multiple tumors (HR, 2.592; 95% CI, 1.666–4.032; p < 0.001), tumor size < 5 cm (HR, 5.239; 95% CI, 3.210–8.550; p < 0.001), vessel invasion (HR, 6.001; 95% CI, 3.717–9.686; p < 0.001), AFP level > 400 ng/mL (HR, 3.769; 95% CI, 2.407–5.903; p < 0.001), poor CTP class (HR, 3.257; 95% CI, 1.886–5.624; p < 0.001), and curative treatment (HR, 0.164; 95% CI, 0.101–0.267; p < 0.001).

Multivariate analysis revealed the following independent prognostic factors for progression-free survival: high hsa_circ_0005986 expression (HR, 0.573; 95% CI, 0.362–0.906; p = 0.017), vessel invasion (HR, 2.657; 95% CI, 1.435–4.921; p = 0.002), and AFP level > 400 ng/mL (HR, 1.702; 95% CI, 1.001–2.892; p = 0.049).

Prediction of hsa_circ_0005986 function

We obtained RNA-seq/miRNA-seq data and clinical information from the TCGA-LIHC dataset, including 425 RNA-seq and 425 miRNA-seq samples (50 normal samples and 374 tumors for RNA-seq; 375 tumors for miRNA-seq), and differentially expressed mRNAs and miRNAs were identified (9004 for mRNA and 310 for miRNA). To further investigate the target of hsa_circ_005986, circBank and WGCNA were performed. Two miRNAs were predicted as target of hsa_circ_005986. The target genes of hsa-mir-3677 and hsa-mir-188 were predicted using mirDB and WGCNA. Finally, we used 2 miRNAs and 52 genes to construct a circRNA–miRNA–mRNA network (Fig. 5A). Figure 5B shows the related biological processes, such as, cell adhesion (p = 0.0015), negative regulation of cell proliferation (p = 0.0044), skeletal system development (p = 0.0062), regulation of inflammatory response (p = 0.013), somatic stem cell maintenance (p = 0.014), and positive regulation of inflammatory response (p = 0.017), all of which were statistically significant.

Discussion

The prognosis of patients with HCC is poor37, in part because most HCC cases are diagnosed at an advanced stage, thereby limiting the treatment options available and resulting in poor overall prognosis38. HCC exhibits various clinical characteristics because of the diverse etiologies associated with the underlying liver disease, impaired hepatic function, and tumor biology, even between the same disease stage. Because the same HCC stage may result in different clinical outcomes, identifying factors that affect prognosis is of great importance. In addition to clinicopathological factors, novel biomarkers can predict tumor recurrence or progression and are currently an active area of investigation.

AFP is a widely used biomarker for HCC; however, it is not specific enough for screening and diagnosing HCC39. Limited progress has been made in identifying new candidate markers, such as des-gamma carboxyprothrombin or fucosylated AFP, which have exhibited low accuracy during clinical evaluation40. Therefore, discovering novel markers is imperative to facilitate timely and early HCC diagnosis and improve treatment success and survival of patients with HCC.

CircRNAs have recently been shown to be potential biomarkers for many cancers, including HCC41,42,43. CircRNAs are promising biomarkers because of their highly stable structure and robust expression patterns in clinical samples. Owing to the covalently closed structure that prevents their cleavage and degradation by exonucleases, circRNAs are highly stable in blood44, saliva45, and exosomes46. As such, they show enormous potential as cancer biomarkers. A previous study showed that the median half-life of tested circRNAs was 2.5-fold longer than that of their linear counterparts from the same gene and showed that circRNAs were stably expressed, whereas mRNA and microRNA expression levels changed within minutes47. Recently, the potential of some circRNAs (circ_005075 and circ_0016788) as HCC diagnostic biomarkers has been suggested48,49. For example, circ-CDYL was upregulated in the early stages of HCC but showed a low AUC value, i.e., 0.6450, which was lower than those reported for circ_005075 and circ_0016788 (0.94 and 0.85, respectively)48,49. Similarly, the development of prognostic biomarkers for HCC has progressed, and some candidates have been identified. Upregulated circ_001569, circ_0008450, and circ_0000267 expressions were associated with poor HCC prognosis suggesting that these circRNAs are independent prognostic markers for HCC51,52,53.

By regulating cell proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, metastasis, and EMT, circRNAs play either an oncogenic or a suppressive role in the progression of HCC25,54,55,56,57. The majority of these processes are regulated by circRNAs via miRNA sponging. For instance, to facilitate tumorigenesis, hsa_circ_101280 serves as a sponge for miR-375 and upregulates JAK2 expression, thereby promoting the proliferation of HCC cells as well as suppressing tumor cell apoptosis54. In addition, the oncogenic role of circSLC3A2 was shown to be dependent on the regulation of PPM1F expression by sponging miR-490-3p56. Another study involving HCC cells revealed higher circASAP1 expression in cells with higher metastatic potential. In addition, circASAP1 was shown to regulate the miR-326/miR-532-5p-MAPK1 pathway, thereby promoting the proliferation of tumor cells in HCC as well as metastasis43. Conversely, circMTO1 and hsa_circ_0001445 were found to promote the expression of the tumor suppressor genes p2125 and TIMP357, respectively. These actions are based on the sponging of miR-925, miR-17-3p, and miR-181b-5p57.

Our study revealed a clear relationship between the patients’ characteristics and hsa_circ_0005986 expression. We showed that hsa_circ_0005986 exhibited reduced expression in HCC and demonstrated that it was associated with clinical and pathological characteristics of patients with HCC. To our knowledge, this is the first study to validate hsa_circ_0005986 as a prognostic biomarker in a HCC cohort by performing survival and regression analyses. In 2017, Fu et al. showed that hsa_circ_0005986 sponged miR-129-5p to regulate NOTCH1 expression in HCC. Downregulated hsa_circ_0005986 expression led to the liberation of miR-129-5p, leading to lower NOTCH1 expression. This was coupled with an accelerated G0/G1 to S phase transition to promote cell proliferation58. The authors also showed an association between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and patient data, which is consistent with our results, except for the correlation of family history with chronic hepatitis B. We did not find an association between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and chronic hepatitis B infection. Moreover, the previous study did not include survival or progression data from 81 patients with HCC. The study by Fu et al. focused on the mechanistic aspect of hsa_circ_0005986 to be considered as a biomarker. On the contrary, our study focused more on the validation of hsa_circ_0005986 as a prognostic biomarker, along with other clinical predictors, based on survival and progression data from a larger number of patients with HCC. Therefore, the difference between this study and the previous study is the validation of a potential prognostic biomarker, hsa_circ_0005986, in a larger HCC cohort, which might be the originality of our study.

We analyzed the whole genome mRNA–miRNA–hsa_circ_0005986 and its interaction network for predicting the role of hsa_circ_0005986 in HCC. On gene ontology analysis, cell adhesion, inhibition of cell proliferation, and skeletal system development were all possibly related to the migration, proliferation, and invasion of HCC. In our study, hsa_circ_0005986 is downregulated in HCC compared with the background liver and also in the higher stages of HCC. These findings were compatible with the potential function of hsa_circ_0005986 as an inhibitor of proliferation. Regulation of the inflammatory response, promotion of the inflammatory response, and somatic stem cell population maintenance might be related to HCC development. Moreover, for predicting the potential mechanism of hsa_circ_0005986, RNA modification or a microbiome should be discussed. Aside from circRNAs relevant to HCC progression and metastasis, RNA modification has also become a popular topic in cancer. Specifically, N4-acetylcytidine modification in other highly stable RNAs, such as circRNA, can be a possible mechanism of aberrant RNA modifications in HCC, which has rarely been studied in the current literature59. On the other hand, there might be a regulation network among immunodeficiency, a microbiome, and circRNA. Immunodeficiency can promote adaptive alterations of the host–gut microbiome and affect cancer development and progression60.

This study has some limitations. First, we did not examine hsa_circ_0005986 expression at a mechanistic level but rather evaluated the association between its expression and clinical endpoints. Further investigation of the mechanism of action of hsa_circ_0005986 is essential. Second, considering the retrospective nature of this study, there may have been some selection bias, considering that patients with missing medical records were not included. We excluded 39 patients who were either lost to follow-up or were previously treated for HCC, which reduced the total number of patients available for analysis. A larger number of patients are needed to validate the associations with hsa_circ_0005986 expression. It is necessary to improve the performance of hsa_circ_0005986 predicting prognoses, specifically for survival and progression. Third, percutaneous needle biopsy performed to obtain the specimens may not adequately reflect tumor heterogeneity. Some pathological features that affect the survival of patients with HCC cannot be assessed using needle biopsies (histological grade, microvascular invasion, and lymphatic invasion). This also reinforces the need to identify noninvasive biomarkers. Noninvasive diagnostic approaches such as serum or exosome collection are needed to validate whether hsa_circ_0005986 can be used as a prognostic biomarker in patients with HCC.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results showed the association between hsa_circ_0005986 expression and HCC proliferation and progression. Considering that hsa_circ_0005986 was shown to be a predictor of HCC progression and survival of patients with HCC, we believe that it has potential to become both a prognostic biomarker and a therapeutic target. However, additional studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying the causal role of hsa_circ_0005986 in HCC progression under the Mendelian Randomization framework through integrating multi-omics datasets61,62,63. In addition, it is important to develop effective individualized therapeutic strategies to help improve the outcomes of patients with HCC.

Data availability

The datasets used or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CircRNA:

-

Circular RNA

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- MiRNA:

-

MicroRNA

- MRE:

-

MiRNA response element

- EMT:

-

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- TNM:

-

Tumor node metastasis

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

- CTP:

-

Child–Turcotte–Pugh

- AFP:

-

Alpha-fetoprotein

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

References

McGuire, S. World Cancer Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, International Agency for Research on Cancer, WHO Press, 2015. Adv. Nutr. 7(418–419), 2016. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.116.012211 (2014).

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359-386. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29210 (2015).

Harding, J. J., Khalil, D. N. & Abou-Alfa, G. K. Biomarkers: what role do they play (if any) for diagnosis, prognosis and tumor response prediction for hepatocellular carcinoma?. Dig. Dis. Sci. 64, 918–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05517-6 (2019).

Pamudurti, N. R. et al. Translation of CircRNAs. Mol. Cell 66(9–21), e27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2017.02.021 (2017).

Barrett, S. P., Wang, P. L. & Salzman, J. Circular RNA biogenesis can proceed through an exon-containing lariat precursor. Elife 4, e07540. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.07540 (2015).

Jeck, W. R. et al. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA 19, 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.035667.112 (2013).

Salzman, J., Chen, R. E., Olsen, M. N., Wang, P. L. & Brown, P. O. Cell-type specific features of circular RNA expression. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1003777 (2013).

Zhang, Y. et al. Circular intronic long noncoding RNAs. Mol. Cell 51, 792–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2013.08.017 (2013).

Memczak, S. et al. Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 495, 333–338. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11928 (2013).

Yu, B. & Shan, G. Functions of long noncoding RNAs in the nucleus. Nucleus 7, 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491034.2016.1179408 (2016).

Lu, Z. et al. Metazoan tRNA introns generate stable circular RNAs in vivo. RNA 21, 1554–1565. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.052944.115 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. The emerging landscape of circular RNAs in immunity: breakthroughs and challenges. Biomark. Res. 8, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40364-020-00204-5 (2020).

Wang, Y. H., Yu, X. H., Luo, S. S. & Han, H. Comprehensive circular RNA profiling reveals that circular RNA100783 is involved in chronic CD28-associated CD8(+)T cell ageing. Immun. Ageing 12, 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12979-015-0042-z (2015).

You, X. et al. Neural circular RNAs are derived from synaptic genes and regulated by development and plasticity. Nat. Neurosci. 18, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3975 (2015).

Szabo, L. et al. Statistically based splicing detection reveals neural enrichment and tissue-specific induction of circular RNA during human fetal development. Genome Biol. 16, 126. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0690-5 (2015).

Lukiw, W. J. Circular RNA (circRNA) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Front. Genet. 4, 307. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2013.00307 (2013).

Barbagallo, D. et al. CircSMARCA5 regulates VEGFA mRNA splicing and angiogenesis in glioblastoma multiforme through the binding of SRSF1. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11020194 (2019).

Zeng, K. et al. CircHIPK3 promotes colorectal cancer growth and metastasis by sponging miR-7. Cell Death Dis. 9, 417. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0454-8 (2018).

Lin, Y. C., Yu, Y. S., Lin, H. H. & Hsiao, K. Y. Oxaliplatin-induced DHX9 phosphorylation promotes oncogenic circular RNA CCDC66 expression and development of chemoresistance. Cancers (Basel). https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12030697 (2020).

Liang, H. F., Zhang, X. Z., Liu, B. G., Jia, G. T. & Li, W. L. Circular RNA circ-ABCB10 promotes breast cancer proliferation and progression through sponging miR-1271. Am. J. Cancer Res. 7, 1566–1576 (2017).

Chen, N. et al. A novel FLI1 exonic circular RNA promotes metastasis in breast cancer by coordinately regulating TET1 and DNMT1. Genome Biol. 19, 218. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1594-y (2018).

Li, P. et al. Circular RNA 0000096 affects cell growth and migration in gastric cancer. Br. J. Cancer 116, 626–633. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.451 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. CircHIPK3 sponges miR-558 to suppress heparanase expression in bladder cancer cells. EMBO Rep. 18, 1646–1659. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201643581 (2017).

Han, D. et al. Circular RNA circMTO1 acts as the sponge of microRNA-9 to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology 66, 1151–1164. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.29270 (2017).

Zhang, X. et al. Down-regulation of hsa_circ_0001649 in hepatocellular carcinoma predicts a poor prognosis. Cancer Biomark. 22, 135–142. https://doi.org/10.3233/CBM-171109 (2018).

Hansen, T. B. et al. Natural RNA circles function as efficient microRNA sponges. Nature 495, 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11993 (2013).

Conn, S. J. et al. The RNA binding protein quaking regulates formation of circRNAs. Cell 160, 1125–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.014 (2015).

Guarnerio, J. et al. Oncogenic role of fusion-circRNAs derived from cancer-associated chromosomal translocations. Cell 165, 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.020 (2016).

Yu, H. et al. LEPR hypomethylation is significantly associated with gastric cancer in males. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 116, 104493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yexmp.2020.104493 (2020).

Chen, J. et al. Genetic regulatory subnetworks and key regulating genes in rat hippocampus perturbed by prenatal malnutrition: implications for major brain disorders. Aging (Albany NY) 12, 8434–8458. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.103150 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Co-expression network analysis identified hub genes critical to triglyceride and free fatty acid metabolism as key regulators of age-related vascular dysfunction in mice. Aging (Albany NY) 11, 7620–7638. https://doi.org/10.18632/aging.102275 (2019).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-9-559 (2008).

Liu, M., Wang, Q., Shen, J., Yang, B. B. & Ding, X. Circbank: a comprehensive database for circRNA with standard nomenclature. RNA Biol. 16, 899–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/15476286.2019.1600395 (2019).

Chen, Y. & Wang, X. miRDB: an online database for prediction of functional microRNA targets. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D127–D131. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz757 (2020).

Torre, L. A. et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 87–108. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21262 (2015).

Llovet, J. M., Burroughs, A. & Bruix, J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet 362, 1907–1917. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1 (2003).

Giannini, E. G. et al. Alpha-fetoprotein has no prognostic role in small hepatocellular carcinoma identified during surveillance in compensated cirrhosis. Hepatology 56, 1371–1379. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.25814 (2012).

Marrero, J. A. et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, des-gamma carboxyprothrombin, and lectin-bound alpha-fetoprotein in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology 137, 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.005 (2009).

Dong, Y. et al. Circular RNAs in cancer: an emerging key player. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-016-0370-2 (2017).

Kristensen, L. S., Hansen, T. B., Veno, M. T. & Kjems, J. Circular RNAs in cancer: opportunities and challenges in the field. Oncogene 37, 555–565. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2017.361 (2018).

Meng, S. et al. CircRNA: functions and properties of a novel potential biomarker for cancer. Mol. Cancer 16, 94. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-017-0663-2 (2017).

Zhang, Y. G., Yang, H. L., Long, Y. & Li, W. L. Circular RNA in blood corpuscles combined with plasma protein factor for early prediction of pre-eclampsia. BJOG 123, 2113–2118. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13897 (2016).

Bahn, J. H. et al. The landscape of microRNA, Piwi-interacting RNA, and circular RNA in human saliva. Clin. Chem. 61, 221–230. https://doi.org/10.1373/clinchem.2014.230433 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Circular RNA is enriched and stable in exosomes: a promising biomarker for cancer diagnosis. Cell Res. 25, 981–984. https://doi.org/10.1038/cr.2015.82 (2015).

Enuka, Y. et al. Circular RNAs are long-lived and display only minimal early alterations in response to a growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 1370–1383. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkv1367 (2016).

Shang, X. et al. Comprehensive circular RNA profiling reveals that hsa_circ_0005075, a new circular RNA biomarker, is involved in hepatocellular crcinoma development. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, e3811. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000003811 (2016).

Guan, Z. et al. Circular RNA hsa_circ_0016788 regulates hepatocellular carcinoma tumorigenesis through miR-486/CDK4 pathway. J. Cell Physiol. 234, 500–508. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.26612 (2018).

Wei, Y. et al. A noncoding regulatory RNAs network driven by circ-CDYL acts specifically in the early stages hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 71, 130–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.30795 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Overexpression of circular RNA circ_001569 indicates poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes cell growth and metastasis by sponging miR-411-5p and miR-432-5p. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 503, 2659–2665. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.020 (2018).

Zhang, J., Chang, Y., Xu, L. & Qin, L. Elevated expression of circular RNA circ_0008450 predicts dismal prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma and regulates cell proliferation, apoptosis, and invasion via sponging miR-548p. J. Cell. Biochem. 120, 9487–9494. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.28224 (2019).

Pan, H. et al. Enhanced expression of circ_0000267 in hepatocellular carcinoma indicates poor prognosis and facilitates cell progression by sponging miR-646. J. Cell. Biochem. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcb.28411 (2019).

Cao, S., Wang, G., Wang, J., Li, C. & Zhang, L. Hsa_circ_101280 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating miR-375/JAK2. Immunol. Cell. Biol. 97, 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/imcb.12213 (2019).

Hu, Z. Q. et al. Circular RNA sequencing identifies CircASAP1 as a key regulator in hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. Hepatology https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31068 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. CircSLC3A2 functions as an oncogenic factor in hepatocellular carcinoma by sponging miR-490-3p and regulating PPM1F expression. Mol. Cancer 17, 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-018-0909-7 (2018).

Yu, J. et al. Circular RNA cSMARCA5 inhibits growth and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 68, 1214–1227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.01.012 (2018).

Fu, L. et al. Hsa_circ_0005986 inhibits carcinogenesis by acting as a miR-129-5p sponge and is used as a novel biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 8, 43878–43888. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.16709 (2017).

Jin, G., Xu, M., Zou, M. & Duan, S. The processing, gene regulation, biological functions, and clinical relevance of N4-acetylcytidine on RNA: a systematic review. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 20, 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omtn.2020.01.037 (2020).

Zheng, S. et al. Immunodeficiency promotes adaptive alterations of host gut microbiome: an observational metagenomic study in mice. Front. Microbiol. 10, 2415. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02415 (2019).

Zhang, F. et al. Causal influences of neuroticism on mental health and cardiovascular disease. Hum. Genet. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00439-021-02288-x (2021).

Zhang, F. et al. Genetic evidence suggests posttraumatic stress disorder as a subtype of major depressive disorder. J. Clin. Invest. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI145942 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Genetic support of a causal relationship between iron status and type 2 diabetes: a Mendelian randomization study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgab454 (2021).

Funding

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grants funded by the Korean government [grant numbers 2017M3A9G8083382, 2019R1A2C1083892, 2021R1A5A2021614, and 2019R1F1A1060878 (Ministry of Science and ICT)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Data curation, G.K., Y.R.L., J.G.P., and M.K.K.; Formal analysis, W.K.L.; Bioinformatics analysis, D.H.K.; Funding acquisition, S.Y.J. and K.H.; Investigation, H.W.L.; Resources, S.Y.P., W.Y.T., Y.O.K., J.R.H., and Y.S.H.; Supervision, S.Y.P. and K.H.; Writing—original draft, G.K., S.Y.J., J.R.H.; Writing—review and editing, S.Y.J. and K.H.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, G., Han, J.R., Park, S.Y. et al. Circular noncoding RNA hsa_circ_0005986 as a prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Rep 11, 14930 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94074-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-94074-y

This article is cited by

-

CircMCTP2 enhances the progression of bladder cancer by regulating the miR-99a-5p/FZD8 axis

Journal of the Egyptian National Cancer Institute (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.