Abstract

The canopy effect describes vertical variation in the isotope ratios of carbon (δ13C), oxygen (δ18O) and partially nitrogen (δ15N) within plants throughout a closed canopy forest, and may facilitate the study of canopy feeding niches in arboreal primates. However, the nuanced relationship between leaf height, sunlight exposure and the resulting variation in isotope ratios and leaf mass per area (LMA) has not been documented for an African rainforest. Here, we present δ13C, δ18O and δ15N values of leaves (n = 321) systematically collected from 58 primate food plants throughout the canopy (0.3 to 42 m) in Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa. Besides leaf sample height and light availability, we measured leaf nitrogen and carbon content (%N, %C), as well as LMA (n = 214) to address the plants’ vertical resource allocations. We found significant variation in δ13C, δ18O and δ15N, as well as LMA in response to height in combination with light availability and tree species, with low canopy leaves depleted in 13C, 18O and 15N and slightly higher in %N compared to higher canopy strata. While this vertical isotopic variation was not well reflected in the δ13C and δ15N of arboreal primates from this forest, it did correspond well to primate δ18O values.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is a remarkable amount of variation in the stable isotope ratios within even one organism. In plants growing in closed canopy forests, leaves measured at varying heights from one individual tree can have markedly different stable isotope ratios of carbon (δ13C), oxygen (δ18O) and to some extent even nitrogen (δ15N). This phenomenon has been widely described1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8 and is commonly referred to as the “canopy effect”9. Isotopic fractionation related to this effect is known to be the result of vertical gradients in sunlight, humidity, availability of atmospheric isotope values, source water and photosynthetic rates. Rather than height from the forest floor, the more ecologically meaningful way of thinking about the canopy effect is probably in terms of depth from the top canopy, as it is the dense structure of intertwining tree crowns that is largely causing these gradients rather than soil-mediated processes permeating upwards into the canopy10. However, by reason of feasibility, canopy effect studies have always considered height from the ground rather than estimating or measuring the depth from the top of the canopy. While most studies focused on δ13C variation within plants, some also included δ18O, δ15N and δ2H7,9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. In this study we investigate plant δ13C, δ18O and δ15N in their relationship to the canopy effect and to stable isotope data of arboreal primate feeding at different canopy heights.

Several processes in the forest canopy cause fractionation and variation in δ13C. In the understory of closed canopy forests, air CO2 is reduced in 13C due to carbon recycling in the form of decomposing leaf litter on the forest floor, which affects the isotope composition of CO2 available for plants growing at different canopy heights2,18,19. Closed canopy forests will also experience significant gradients of photosynthetically available radiation (PAR) as the upper canopy can block between 95 and 99.5% of all light from ever reaching the forest floor20. In the lower canopy where lower light and temperature reduce transpiration rates, leaves can afford maximum stomatal opening. Here, diffusion of CO2 is high and the enzyme rubisco will preferentially fix 12CO2 while discriminating the heavier 13CO2. These leaves will have more negative δ13C values. However, in the upper canopy, where potentially high evaporative flux can lead to stomatal closure to conserve water, rubisco will fix 13CO2 at a higher rate than in the understory. Hence, upper canopy leaves will have higher δ13C values21 (and references therein). The canopy effect is often measured in forests with very large trees, such as in large conifers, which will compensate for hydraulic constraints due to gravity by modifying various traits associated with water transport and photosynthesis22,23,24.

Variation in δ18O within the forest canopy is mainly driven by atmospheric humidity levels. Low relative humidity in the upper canopy tends to lead to higher rates of transpiration7,14. Preferential loss of lighter H216O during evaporation will leave leaf tissue enriched in remaining 18O. Besides rates of evaporation, the δ18O composition of plant water is primarily determined by the isotope composition of source water in the soil, which vary geographically and is affected by local surface air temperature, altitude, amount of precipitation, etc.12,25,26. The canopy effect in δ18O, with δ18O values varying with canopy height, has been reported for tropical forest ecosystems with closed canopy cover7,14, yet not all studies could find a clear difference between understory and canopy leaves δ18O11.

δ15N values in non-leguminous plants are determined by the isotopic composition of the source soil27. δ15N is predicted to fluctuate between ecological zones based on variation in temperature and precipitation as well as mycorrhizal activity27. While epiphytes are seen to experience different rates of δ15N fractionation with canopy height16, fractionation of δ15N within individual leaves has not been seen to be affected by height in trees11. In this study, we explore whether leaf δ15N values vary with canopy height, which has only been documented in a few cases8.

The considerable gradient in light intensity within the canopy does not only affect isotope fractionation, but also the chemical and structural makeup of the leaves, such as leaf mass per area (LMA). Similar to the canopy effect in isotopes, leaf structure varies with canopy height to maximize radiation-use efficiency and photosynthetic rate with varying levels of light intensity within the canopy. Understory leaves experiencing shade conditions will maximize their radiation-use efficiency by compensating with larger, thinner leaves (lower LMA) to increase photon capture7,21,28. In shade leaves, nitrogen is preferentially allocated to components of light-harvesting processes, whereas sun leaves invest nitrogen into rubisco. However, with increasing height, hydraulic limitations due to gravity, and water stress imposed by greater vapor pressure deficit, leaves will increasingly invest in water saving strategies to optimize water use efficiency7,29. These high canopy leaves tend to be smaller than their shade-adapted counterparts, with more numerous and larger cells to increase leaf capacitance, altogether making the leaf thicker (higher LMA) and thus more resilient to water loss21. This variation in LMA within the forest canopy should have consequences for the material properties and nutritional value of leaves as well as herbivore food preference30,31.

The predictability of the canopy effect in the stable isotope ratios of forest plants allows for the study of feeding and foraging behavior in elusive or extinct species of primates and arboreal animals by means of stable isotopes32,33. Isotopic variation in leaves and fruits due to height differences in the canopy can be expected to be reflected in the hair, bones, and teeth of primates which feed on these various plant food items34,35. In tropical forests around the world, arboreal primate species occupy specific spatial niches within the vertical strata of the canopy36(and references therein). Long term field studies have observed primate species of the genera Colobus, Cercopithecus, and Cercocebus displaying habitat preference within the canopy of the rainforest of Taï National Park in Côte d’Ivoire, with different sympatric primates occupying different strata within the rainforest canopy. Body size constraints and dietary niches seem to drive spatial differentiation for Taï’s arboreal primates, and this is most pronounced during inter-specific associations37. Variations in branch size and stability as well as plant material properties and possibly uneven nutrient availability within the canopy are assumed to correlate with a vertical stratification of feeding niches occupied by different sympatric arboreal primate species34. An isotope study carried out in Taï National Park, measured the δ13C and δ18O values in primate bone collagen and apatite to determine the extent to which isotopes reflected this stratification in the canopy34. While variation in δ13C values was in large part a reflection of mixed diets rather than height in the canopy33,38, the study found strong correlation between δ18O values and canopy strata use. This is interesting as while δ13C and δ15N mainly relate to the isotopic characteristics of ingested foods, δ18O in animal bodies can be determined by not only the food, but much more so by drinking water and air39. Arboreal primates are commonly assumed to mainly rely on water deriving directly from plant foods40. This would suggest that leaf δ18O values will considerably affect the δ18O values of these primates, which we will test in this study.

In this study, we explore the canopy effect in plant foods which is underlying the isotopic variation found in these arboreal primates, by reporting bulk organic δ13C, δ18O and δ15N baseline values in 321 leaves of 58 individual plants collected at a range of heights between the understory and emergent trees (0.3 to 42 m) of Taï National Park (Table 1). These consist of 12 plant species for which long-term observation records show that they are particularly relevant for the diet of both chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes versus) and the different arboreal primates of Taï forest37,41 (unpublished data, Boesch & Wittig, personal communications McGraw). We here aim at establishing a multi-isotope baseline for future research on canopy stratigraphy and arboreal feeding niches in this and other rainforest ecosystem, which has the potential to also inform paleoecological reconstructions of forest species communities in the fossil record33,42.

We predicted that the leaves of the tallest trees, exposed to higher proportions of radiation, will modify their structure to accommodate for high rates of photosynthesis and evaporation. As a result of this strategy and other factors summarized under the canopy effect (e.g. increase in humidity, changes in availability of atmospheric vs. respirated CO2), leaf δ13C and δ18O values will strongly correlate with sampling height in interaction with light (PAR), producing the lowest isotope values in the forest understory and the highest values in leaves of emergent trees5,6. We had no such clear predictions for leaf δ15N values, as few studies found any significant variation in δ15N with height in the canopy8,16. Further, we investigated how leaf height and light availability affect leaf structure in an effort to better understand and describe the underlying mechanisms associated with isotopic fractionation. We predicted that LMA measurements (n = 214) will be lowest in understory plants and highest in emergent trees. We further anticipated that nitrogen content (%N) of leaves may be negatively correlate with LMA as smaller more shaded leaves should invest into higher photosynthetic capacity. Finally, we considered how leaf mass and %N may have implications for the material properties of leaves and thus relevance for primate feeding behavior.

Results

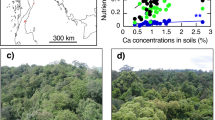

We collected 321 leaves from 58 understory plants, vines, mid canopy trees and emergent trees of 12 species at ~ 1 m intervals ranging from the forest floor up to the highest point in the canopy (42 m) and documented considerable variation in PAR (Fig. 1). In this sample, we recorded considerable variation of δ13C (− 40 to − 26.7‰, mean = − 32.9‰), δ18O (20.5 to 31.4‰, mean = 26.4‰) and δ15N values (− 1.9 to 7.2‰, mean = 4.3‰). LMA values (mean = 90.8 g/m2) varied considerably between samples, ranging from 28.6 to 247.1 g/m2 (Fig. 2a–d, Table S1).

We ran four models to test the effects of height (m) in interaction with PAR (μmol m−2 s−1), tree species, %N and %C and the random effect of plant individual on the response variables δ13C, δ18O, δ15N (‰) and LMA (g/m2). All models were highly significant, suggesting that height and PAR, or the interaction of both, as well as %N, %C and tree species have significant effects on δ13C, δ18O and δ15N values and LMA (Table 2, see Table S2 for detailed model results). The δ13C model was highly significant (χ2 = 417.3, df = 16, p < 0.0001) and showed that while %C was not significantly affecting δ13C values, the effect of height interacting with PAR was significant and tree species was highly significant, with higher and more light exposed leaves revealing significantly higher δ13C values (see Fig. 3a). The δ18O model was also highly significant (χ2 = 108, df = 16, p < 0.0001). Here the main driving effects were again sample height interacting with PAR and also tree species, with increasing height and PAR resulting in significantly higher δ18O values (Fig. 3b). The δ15N model without an interaction between sample height and PAR was significant as well (χ2 = 76, df = 15, p < 0.0001). Here, tree species was highly significant, whereas %N and the effect of PAR were significant, with lower light exposure resulting in lower leaf δ15N values (Fig. 3c). Sampling height had no effect on δ15N values of leaves and neither did %C. Finally, the LMA model was also highly significant (χ2 = 214, df = 14, p < 0.0001). Here the main driving effects were identified to be particularly %N, tree species and the interacting covariates height and PAR. Increasing height and PAR consistently lead to higher LMA and reductions in %N across plant species (Fig. 3d). The variable %C however had no effect on the LMA of leaves in this study (Table 2).

3-D plots illustrating the joint effects of sampling height (m) and PAR (umol) within the forest canopy on the (a) δ13C (VPDB), (b) δ18O (VSMOW), (c) δ15N (AIR), as well as (d) LMA values of leaves in μmol m−2 s−1. Different data point colors relate to different plant types within the plants sampled in this study. The single outlier data point from the vine species Landolphia foretiana (Lan.2.1) was excluded from our statistical data analysis.

Discussion

For plants growing in a competitive regime, strategies which maximize light efficiency or water efficiency will result in very different structural and nutrient partitioning strategies which will likely have consequences for isotopic fractionation within plant parts. This study documents the gradual changes in leaf isotope ratios in response to absolute height and the sunlight available for photosynthesis and responsible for leaf water evaporation, and thus provides further evidence on the so-called canopy effect in δ13C, δ18O and even δ15N.

First, height and evapotranspirative demand are known to impact carbon and oxygen discrimination in leaves along the canopy height gradient. Leaf water potentials decrease with increasing elevation due to longer water transport path lengths, as well as the downward pull of gravity on the water column29,43. Consequently, upper canopy leaves will reduce their stomatal conductance in response to the perceived lower water availability23. Furthermore, leaves will also reduce stomatal conductance under increased vapor pressure deficit, brought about by the lower humidity levels typically experienced in the higher strata of the forest canopy21,44.

Also, light availability shapes the structural and functional trade-offs of leaves growing at the top of the canopy as well as in the understory. The level of radiation able to permeate the dense upper canopy will play an important role in determining understory productivity so it is important to account for heterogeneity in light composition in the understory by measuring PAR at consistent intervals in the canopy45. Solar radiation is a driver of photosynthetic rates, relative humidity levels and evaporation rates in the forest interior. Indeed, δ13C and δ18O values as well as measures of LMA, all of which are highly influenced by photosynthetic rate and evaporation respectively, were highly correlated with PAR (Fig. 3a,b,d). Emergent trees in our dataset consistently received the highest levels of PAR; leaves sampled from these trees also had the highest δ13C values, as well as some of the highest values in δ18O, δ15N and LMA. Similarly, samples obtained from understory plants received some of the lowest levels of PAR and subsequently show the lowest values of δ13C, δ18O, δ15N and LMA (Figs. 2 and 3). These results are consistent with our prediction that the tallest trees, which are able to capture high proportions of radiation incident on a tree canopy, will modify their leaf structure to account for high rates of photosynthesis and evaporation and will be enriched in 13C and 18O respectively13,21.

Our measurements of δ13C values in leaf tissue were highly correlated with the dynamic effect of height interacting with light (Fig. 3a). We found a large variation of δ13C values within the canopy of this forest [− 40 to − 26.7‰] also in accordance to the higher rates of CO2 cycling occurring in leaves lower in the canopy due to lower evaporative stress and higher stomatal conductance46. In general, the δ13C values we report here are more negative than the δ13C variation previously found in rainforest canopies2,7,11,47,48 with the exception of a few understory plants in the Congo Basin49. These particularly low δ13C values in the understory of Taï forest could be explained by unusually low rates of air circulation and high rates of recycling of respiratory CO21,50. Given that high humidity levels should also increase isotopic fractionation in the forest understory13. It should be noted that field sampling took place during the relatively wet rainy season and daily humidity levels were high.

Measurements of bulk leaf material δ18O values were also highly predicted by the interacting effects of height and light in the canopy (Fig. 3b). While some previous work found similar canopy effects in closed canopy forest plant δ18O7, others were not able to reproduce this pattern in smaller and more diverse plant part samples11. The variation in our measurements of δ18O values of these leaves throughout the canopy was considerable [20.5 to 31.4‰] and δ18O values were more negative as compared to past studies (Table S1)7,11, possibly because Taï forest may experience higher average temperatures and evapotranspiration compared to other field sites.

While previous research found no or only an inconsistent positive effect of height in δ 15N values8,11,16,17, we found a significant correlation between PAR and δ15N values, as well as a larger within-canopy variation in δ 15N values than reported so far. However, we did not find a significant relationship between δ 15N values and height directly, suggesting that variation in δ15N values may not be linked to what we call the canopy-effect per se (Figs. 2c, 4b). Our understanding so far is that δ 15N values in plants are highly dependent on the δ15N ratios of the source soil as well as any symbiotic associations rather than height or hydraulic limitations51. Ometto and colleagues8 found slight, but significantly lower understory δ15N values compared to the higher forest layers in two out of four sites measured in the Amazon, suggesting this may be related to different nitrogen sources in the soil, e.g. through the higher uptake of NO3 by understory vegetation. Height also affected δ15N values in epiphytes but was assumed to be associated to fractionation during nitrogen acquisition and mycorrhizal associations and possibly also related to water stress16. As in our study height was not a driving factor in leaf δ15N variation, we assume that PAR related evaporation stress may partly explain the fractionation of δ15N in leaves, and less so nitrogen source.

Whisker plots showing the distribution of (a) δ13C, (c) δ15N, and (b) δ18O values in leaves of different plant types (legends Figs. 1, 2, 3) across the canopy strata occupied by arboreal primate species at Taï forest. Average primate isotope data from bone collagen (a,b) and carbonate (c) are shown by canopy strata use as pink diamonds (± 1σ SD). The low canopy is most used by the taxa Cercocebus atys and Cercopithecus campelli, mid canopy is most relevant for C. petaurista, C. diana and Procolobus verus, whereas high canopy levels are inhabited by Procolobus badius and Colobus polykomos37. Vertical niche differentiation is best reflected by δ18O.

Low levels of light in the understory have profound impacts on light acquisition morphology of “shade leaves”, which tend to have higher levels of chlorophyll, and larger, thinner leaves to improve light capturing efficiency21,52. We found a significant correlation between leaf LMA and height (Fig. 3d), as well as significant variation in LMA between plant species (Fig. 2d). Leaves of vines and understory plants had consistently lower LMA measures compared to emergent and midcanopy trees. Emergent and midcanopy trees will experience higher degrees of water stress due to gravity and evaporation, especially in the upper canopy, and will adjust their leaf physiology to conserve water loss. However, vines and understory plants experience less water stress and may be less likely to grow leaves suited for water conservation21. The relationship between leaf toughness and height has implications for primate food preference as primates can be assumed to select for high energy yields which involve the least handling and masticatory investment53. Thus, primates may prefer leaves with low LMA in the lower canopy, which are thinner, presumably less tough and hence require less mastication energy over high canopy leaves30. High canopy leaves or “sun leaves” are expected to have higher toughness and require higher energy usage to consume30,54. In their 2008 study, Onoda and colleagues measured leaf toughness as a product of LMA and “punch strength” or maximum force/area and found that the toughness of sun leaves was mainly determined by their high LMA. The correlation we found between height, PAR and LMA in leaves from Taï forest makes LMA an interesting parameter for future work on the canopy effect and primate isotope ecology.

We also found a highly significant negative correlation between LMA and %N (Table 2) in our leaf samples. Low light leaves invest more nitrogen into light harvesting pigments, such as chlorophyll, for greater light capturing efficiency28. Alternatively, leaves in the upper canopy experience light-saturated rates of photosynthesis and will invest in enzymes associated with carbon fixation, mainly rubisco, to enhance their photosynthetic capacity21. Hence, our findings also suggest that leaf %N varies indirectly with height, which may affect primate feeding behavior. Primates are thought to prefer leaves with high protein content55. Since fruits are low in protein, primates not obtaining protein from invertebrate or vertebrate foods, will rely on leaves for a large portion of the protein in their diet and may preferentially select foliage high in nitrogen56,57. While this variation in %N is minimal, ranging from ~ 1 to 3.5 weight%, it might be of relevance to folivorous primates in combination with LMA and leaf toughness (see below).

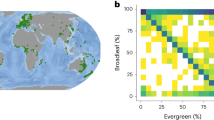

Primates living in Taï National Park, grossly group into the feeding niches low (> 10 m, Cercocebus atys and Cercopithecus campelli), mid (10–20 m, C. petaurista, C. diana and Procolobus verus) and high (< 20, Procolobus badius and Colobus polykomos) canopy, which differ clearly in the stable isotope ratios of leaves (Fig. 4). Our leaf isotope data would suggest that feeding heights should be most clearly detectable in primate δ13C and δ18O values and could even have a slight effect on δ15N. However, Fig. 4 shows that the isotope signatures of Taï primates feeding at different height categories do not match well with those in leaves in δ13C or δ15N, but they do correspond well to the leaf δ18O values. The δ13C canopy effect is barely reflected in the collagen and apatite δ13C values of seven different arboreal primate species within Taï forest34. This notion, that feeding behaviors will substantially shift the δ13C values from what we would expect from mammals living in a closed canopy rainforest, is now well described for African and Amazonian rainforest58. Primates feeding in the understory and shrub layer up to 10 m heights have δ13C values similar to primates feeding in the highest canopy although understory leaves are on average ~ 5‰ lower in δ13C. In fact, all primates measured by Krigbaum and colleagues34 have bone collagen δ13C values much higher than the foliage in their canopy strata would predict (Fig. 4a). This can be explained by the systematic differences in δ13C between photosynthetic (leaves) and heterotrophic (flowers, fruits, seeds, bark, stem) plant parts, with leaves always being several ‰ lower in δ13C compared to other plant organs17,59. We can expect that fruit and seed eating primates will always have higher δ13C values than their folivorous counterparts, even if they forage in the forest understory such as sooty mangabeys (Cercocebus atys). And indeed, the most folivorous primate at Taï, the olive colobus monkey (Procolobus verus) had the lowest δ13C values among all taxa34. In sum, the degree of folivory versus frugivory should be accounted for when using δ13C in reconstructing canopy strata use60.

Our study suggests that δ18O has the potential to be a much more reliable tool in reconstructing canopy feeding niche than δ13C because δ18O values in plant foods will vary significantly with height7,14 (Fig. 4b) without the systematic isotopic offsets between leaves and heterotrophic plant parts we see in δ13C11. This suggests that the δ18O data should correspond well to the δ18O values of primate consumers. Indeed, the best predictor for feeding height in primate skeletal remains was previously shown to be δ18O, irrespective of the degree of folivory or frugivory34,60. We can confirm this here when we compare our results with the carbonate δ18O values of arboreal primates feeding at different heights in the same forest (Fig. 4c). This makes this isotope system particularly interesting for canopy feeding niche reconstructions in primates38,61. It is possible that atmospheric O2 and water vapor, other important sources of body water39, may also vary throughout the different strata of the forest canopy and contribute to this observed pattern. This will remain to be tested. Rainwater accumulations in tree holes may be an additional source of water undergoing different rates of evaporation in the forest canopy, though their use has not been described for the primates mentioned in this study40.

Our data suggest that δ15N has the potential to gain relevance in the study of canopy niches as well. When we group the δ15N values into three categories low (0–10 m), mid (10–20 m), and high (20–42 m) as shown in Fig. 4b, it becomes clear that mid and high canopy leaves are indistinguishable in δ15N, but low canopy leaves are on average ~ 1‰ lower in δ15N (mean 3.6 ± 1.4‰ 1σ) than leaves higher than 10 m (4.7 ± 1.2 δ15N‰ 1σ). However, this effect is barely visible, e.g. in the δ15N values of low canopy foraging primates at Taï (see Fig. 4b), such as the sooty mangabeys and diana monkeys (Cercopithecus diana)34. Nevertheless, that canopy height may affect δ15N values of plant foods may find some consideration in future isotopic research as an effect which may interfere with interpretations of faunivory and trophic level62.

This isotope study on the canopy effect in primate foods is limited to mature leaves out of logistical reasons as the timing of flowering, fruiting and young leaf flushing can be unpredictable and stretch over many months. Canopy research however, is extremely risky and should involve the presence of experienced certified arborists, which rarely are available for fieldwork months on end. Nevertheless, we are confident that similar isotopic effects we describe for leaves will also likely be found in other forest plant foods. Non-photosynthetically active plant parts such as fruits, flowers and seeds can be expected to source their water and energy from proximate sources within the plant, e.g. from adjacent leaves via phloem translocation63. A previous study on the canopy effect suggested that young and mature leaves do not substantially differ in δ13C or δ18O and mature foliage and fruits did not differ in δ18O11. On the other hand, isotopic fractionation between specific plant organs are well described for δ13C and allows us to correct plant δ13C data for plant part17,59. In sum, it is important to understand that both plant part and canopy height can be expected to significantly affect the δ13C ratios of plant foods, whereas canopy height and water source will be the stronger predictor for δ18O. This suggests that sampling of various primate plant food species remains crucial for research in primate isotope ecology when focusing on nuanced effects of canopy niche and dietary adaptations.

Methods

This study was conducted in compliance with all relevant institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation. None of the plant species selected for this study are listed by the IUCN as endangered species. Voucher specimens (for IDs see Table S1) identified by F. G. Gnimion, are stored and publically available at the Primate Ecology and Molecular Anthropology Laboratory at the University of California Santa Cruz. Field work was conducted under research authorization permit 067/MESRS/DGRI/DR issued by the Ministre de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche scientifique, Côte d’Ivoire. We collected mature leaves at ~ 1 m increments for 58 individuals of 12 different plant species (total n = 321) consumed by primates in the research area of the Taï Chimpanzee Project, located in the primary rainforest of Taï National Park, Côte d’Ivoire, West Africa (Table 1, also see Supplementary Materials). Sampling was mostly accomplished by using rope access tree climbing techniques64 under the support of arborist James Luce. For each leaf sample we identified and recorded species, plant ID, date, time of day and %cloud cover. During sampling we measured exact height (m) with a measuring tape lowered to the forest floor and PAR with a handheld quantum light sensor (see Table S1 for the full dataset and SI for detailed sampling description). All samples were imported to the USA in compliance with national guidelines under USDA APHIS import permits PCIP-17-00383 and PCIP-20-00092. Samples were dried down, homogenized and weighed for stable isotope analysis at the Stable Isotope Laboratory of the University of California, Santa Cruz. Nitrogen (%N) and carbon content (%C) were measured alongside δ13C and δ15N via a Dumas combustion using a 1108 elemental analyzer (Carlo Erba, Chaussée du Vexin, France) coupled to a Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass-spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan, Bremen, Germany). For the analysis of bulk leaf material δ18O we used a Thermo-Chemical Elemental Analyzer (Thermo-Finnigan, Bremen, Germany) also coupled to a Delta Plus XP isotope ratio mass-spectrometer. The resulting isotope data is reported here in ‰ (or mUr). Analytical precision was better than 0.2‰ for δ13C and δ15N, and better than 0.3‰ for δ18O.

We measured LMA in initially dried intact leaves, which were later rehydrated at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Dry leaves were weighed prior to rehydration and leaf area was measured using a LI-3100 Area Meter (cm2; LI-COR inc. Lincoln, Nebraska USA).

Using four linear mixed effects models we statistically analyzed the effects of height in interaction with PAR, tree species, %N and %C and the random effect of plant individual on the response variables δ13C, δ18O, δ15N and LMA (please see the Supplementary Materials for detailed material and method descriptions).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article as Supplementary Information file.

References

Vogel, J. Recyling of carbon in a forest environment. Oecol. Plant. 13, 89–94 (1978).

Medina, E. & Minchin, P. Stratification of δ 13C values of leaves in Amazonian rain forests. Oecologia 45, 377–378 (1980).

Ehleringer, J. R., Field, C. B., Lin, Z. & Kuo, C. Leaf carbon isotope and mineral composition in subtropical plants along an irradiance cline. Oecologia 70, 520–526 (1986).

Medina, E., Sternberg, L. & Cuevas, E. Vertical stratification of δ13C values in closed natural and plantation forests in the Luquillo mountains, Puerto Rico. Oecologia 87, 369–372 (1991).

Graham, H. V. et al. Isotopic characteristics of canopies in simulated leaf assemblages. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 144, 82–95 (2014).

Buchmann, N., Kao, W.-Y. & Ehleringer, J. Influence of stand structure on carbon-13 of vegetation, soils, and canopy air within deciduous and evergreen forests in Utah, United States. Oecologia 110, 109–119 (1997).

Sternberg, L. D. S. L., Mulkey, S. S. & Wright, S. J. Oxygen isotope ratio stratification in a tropical moist forest. Oecologia 81, 51–56 (1989).

Ometto, J. P. H. B. et al. The stable carbon and nitrogen isotopic composition of vegetation in tropical forests of the Amazon Basin, Brazil. Biogeochemistry 79, 251–274 (2006).

van der Merwe, N. J. & Medina, E. The canopy effect, carbon isotope ratios and foodwebs in Amazonia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 18, 249–259 (1991).

Houle, A. & Wrangham, R. W. Contest competition for fruit and space among wild chimpanzees in relation to the vertical stratification of metabolizable energy. Anim. Behav. 175, 231–246 (2021).

Roberts, P., Blumenthal, S. A., Dittus, W., Wedage, O. & Lee-Thorp, J. A. Stable carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen, isotope analysis of plants from a South Asian tropical forest: Implications for primatology. Am. J. Primatol. 79, e22656 (2017).

Barbour, M. M. Stable oxygen isotope composition of plant tissue: A review. Funct. Plant Biol. 34, 83–94 (2007).

Cernusak, L. A. et al. Stable isotopes in leaf water of terrestrial plants. Plant Cell Environ. 39, 1087–1102 (2016).

Ometto, J. P. H., Flanagan, L. B., Martinelli, L. A. & Ehleringer, J. R. Oxygen isotope ratios of waters and respired CO2 in Amazonian forest and pasture ecosystems. Ecol. Appl. 15, 58–70 (2005).

Yakir, D. Variations in the natural abundance of oxygen-18 and deuterium in plant carbohydrates. Plant Cell Environ. 15, 1005–1020 (1992).

Wania, R., Hietz, P. & Wanek, W. Natural 15N abundance of epiphytes depends on the position within the forest canopy: Source signals and isotope fractionation. Plant Cell Environ. 25, 581–589 (2002).

Blumenthal, S. A., Rothman, J. M., Chritz, K. L. & Cerling, T. E. Stable isotopic variation in tropical forest plants for applications in primatology. Am. J. Primatol. 78, 1041–1054 (2016).

Schleser, G. H. & Jayasekera, R. 13C-variations of leaves in forests as an indication of reassimilated CO2 from the soil. Oecologia 65, 536–542 (1985).

van der Merwe, N. J. & Medina, E. Photosynthesis and 13C12C ratios in Amazonian rain forests. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 1091–1094 (1989).

Chazdon, R. L. & Pearcy, R. W. The importance of sunflecks for forest understory plants. Bioscience 41, 760–766 (1991).

Lambers, H., Chapin, F. S. & Pons, T. L. Plant Physiological Ecology (Springer New York, 2008) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-78341-3.

Hellkvist, J., Richards, G. P. & Jarvis, P. G. Vertical gradients of water potential and tissue water relations in sitka spruce trees measured with the pressure chamber. J. Appl. Ecol. 11, 637–667 (1974).

Ambrose, A. R., Sillett, S. C. & Dawson, T. E. Effects of tree height on branch hydraulics, leaf structure and gas exchange in California redwoods. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 743–757 (2009).

Peltoniemi, M. S., Duursma, R. A. & Medlyn, B. E. Co-optimal distribution of leaf nitrogen and hydraulic conductance in plant canopies. Tree Physiol. 32, 510–519 (2012).

Araguás-Araguás, L., Froehlich, K. & Rozanski, K. Deuterium and oxygen-18 isotope composition of precipitation and atmospheric moisture. Hydrol. Process. 14, 1341–1355 (2000).

Gonfiantini, R., Roche, M.-A., Olivry, J.-C., Fontes, J.-C. & Zuppi, G. M. The altitude effect on the isotopic composition of tropical rains. Chem. Geol. 181, 147–167 (2001).

Craine, J. M. et al. Global patterns of foliar nitrogen isotopes and their relationships with climate, mycorrhizal fungi, foliar nutrient concentrations, and nitrogen availability. New Phytol. 183, 980–992 (2009).

Guenni, O., Romero, E., Guédez, Y., Bravo de Guenni, L. & Pittermann, J. Influence of low light intensity on growth and biomass allocation, leaf photosynthesis and canopy radiation interception and use in two forage species of Centrosema (DC.) Benth. Grass Forage Sci. 73, 967–978 (2018).

Ryan, M. G. & Yoder, B. J. Hydraulic limits to tree height and tree growth. Bioscience 47, 235–242 (1997).

Dunham, N. T. & Lambert, A. L. The role of leaf toughness on foraging efficiency in Angola black and white colobus monkeys (Colobus angolensis palliatus). Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 161, 343–354 (2016).

Poorter, L., van de Plassche, M., Willems, S. & Boot, R. G. A. Leaf traits and herbivory rates of tropical tree species differing in successional status. Plant Biol. 6, 746–754 (2004).

Sponheimer, M. et al. Using carbon isotopes to track dietary change in modern, historical, and ancient primates. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 140, 661–670 (2009).

Nelson, S. V. Chimpanzee fauna isotopes provide new interpretations of fossil ape and hominin ecologies. Proc. R. Soc. B 280, 20132324 (2013).

Krigbaum, J., Berger, M. H., Daegling, D. J. & McGraw, W. S. Stable isotope canopy effects for sympatric monkeys at Taï Forest, Côte d’Ivoire. Biol. Lett. 9, 20130466 (2013).

Oelze, V. M., Head, J. S., Robbins, M. M., Richards, M. & Boesch, C. Niche differentiation and dietary seasonality among sympatric gorillas and chimpanzees in Loango National Park (Gabon) revealed by stable isotope analysis. J. Hum. Evol. 66, 95–106 (2014).

McGraw, W. S. Positional behavior of Cercopithecus petaurista. Int. J. Primatol. 21, 157–182 (2000).

McGraw, W. S. Comparative locomotion and habitat use of six monkeys in the Tai Forest, Ivory Coast. Am. J. Primatol. 105, 493–510 (1998).

Carter, M. L. & Bradbury, M. W. Oxygen isotope ratios in primate bone carbonate reflect amount of leaves and vertical stratification in the diet. Am. J. Primatol. 78, 1086–1097 (2016).

Bryant, J. D. & Froelich, P. N. A model of oxygen isotope fractionation in body water of large mammals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 59, 4523–4537 (1995).

Sharma, N. et al. Watering holes: The use of arboreal sources of drinking water by Old World monkeys and apes. Behav. Proc. 129, 18–26 (2016).

Wittig, R. M. Taï chimpanzees. In Encyclopedia of Animal Cognition and Behavior (eds Vonk, J. & Shackelford, T.) 1–7 (Springer International Publishing, 2017) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47829-6_1564-1.

Nelson, S. V. & Rook, L. Isotopic reconstructions of habitat change surrounding the extinction of Oreopithecus, the last European ape. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 160, 254–271 (2016).

Ryan, M. G., Phillips, N. & Bond, B. J. The hydraulic limitation hypothesis revisited. Plant Cell Environ. 29, 367–381 (2006).

Bachofen, C., D’Odorico, P. & Buchmann, N. Light and VPD gradients drive foliar nitrogen partitioning and photosynthesis in the canopy of European beech and silver fir. Oecologia 192, 323–339 (2020).

Chazdon, R. L., Williams, K. & Field, C. B. Interactions between crown structure and light environment in five rain forest piper species. Am. J. Bot. 75, 1459–1471 (1988).

Ambrose, A. R. et al. Hydraulic constraints modify optimal photosynthetic profiles in giant sequoia trees. Oecologia 182, 713–730 (2016).

Voigt, C. C. Insights into strata use of forest animals using the ‘canopy effect’. Biotropica 42, 634–637 (2010).

Ometto, J. P. H. B. et al. Carbon isotope discrimination in forest and pasture ecosystems of the Amazon Basin. Brazil. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 16, 56-1-56–10 (2002).

Loudon, J. E. et al. Stable isotope data from bonobo (Pan paniscus) faecal samples from the Lomako Forest Reserve, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Afr. J. Ecol. 57, 437–442 (2019).

Medina, E., Klinge, H., Jordan, C. & Herrera, R. Soil respiration in Amazonian rain forests in the Rio Negro Basin. Flora 170, 240–250 (1980).

Craine, J. M. et al. Ecological interpretations of nitrogen isotope ratios of terrestrial plants and soils. Plant Soil 396, 1–26 (2015).

Niinemets, Ü. & Tenhunen, J. D. A model separating leaf structural and physiological effects on carbon gain along light gradients for the shade-tolerant species Acer saccharum. Plant Cell Environ. 20, 845–866 (1997).

Schoener, T. W. Theory of feeding strategies. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2, 369–404 (1971).

Onoda, Y., Schieving, F. & Anten, N. P. R. Effects of light and nutrient availability on leaf mechanical properties of plantago major: A conceptual approach. Ann. Bot. 101, 727–736 (2008).

Dasilva, G. L. Diet of Colobus polykomos on Tiwai Island: Selection of food in relation to its seasonal abundance and nutritional quality. Int. J. Primatol. 15, 655–680 (1994).

Rothman, J. M., Chapman, C. A. & Pell, A. N. Fiber-bound nitrogen in gorilla diets: Implications for estimating dietary protein intake of primates. Am. J. Primatol. 70, 690–694 (2008).

Ganzhorn, J. U. et al. The importance of protein in leaf selection of folivorous primates. Am. J. Primatol. 79, e22550 (2017).

Tejada, J. V. et al. Comparative isotope ecology of western Amazonian rainforest mammals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 117, 26263–26272 (2020).

Cernusak, L. A. et al. Why are non-photosynthetic tissues generally 13C enriched compared with leaves in C3 plants? Review and synthesis of current hypotheses. Funct. Plant Biol. 36, 199–213 (2009).

Fannin, L. D. & McGraw, W. S. Does oxygen stable isotope composition in primates vary as a function of vertical stratification or folivorous behaviour?. Folia Primatol. 91, 219–227 (2020).

Crowley, B. E., Melin, A. D., Yeakel, J. D. & Dominy, N. J. Do oxygen isotope values in collagen reflect the ecology and physiology of neotropical mammals?. Front. Ecol. Evol. 3, 127 (2015).

DeNiro, M. J. & Epstein, S. Influence of diet on the distribution of nitrogen isotopes in animals. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 45, 341–351 (1981).

Lemoine, R. et al. Source-to-sink transport of sugar and regulation by environmental factors. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 272 (2013).

Anderson, D. L., Koomjian, W., French, B., Altenhoff, S. R. & Luce, J. Review of rope-based access methods for the forest canopy: Safe and unsafe practices in published information sources and a summary of current methods. Methods Ecol. Evol. 6, 865–872 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this article to the late James Luce (*1953- †2020), outstanding arborist, adventurer, tree climbing mentor and friend, without whom this study would not have been possible. Our local plant expert and field assistant Florent Gnonsian Gnimion helped with plant identification. Virgile Manin helped with fieldwork logistics. We are grateful to Colin Carney and Dyke Andreasen from the UCSC Stable Isotope Laboratory for their invaluable assistance with sample measurement. Gaëlle Bocksberger helped with the graphics. Alain Houle provided valuable feedback on this manuscript. Sylvain Lemoine extracted TCP long term feeding data to help with the identification of the most important leaf species for the Taï chimpanzees and Scott McGraw commented on the selection of tree species relevant for the arboreal primates of Taï. We are grateful to the two reviewers who helped improve this manuscript. We thank the Ministère de l'Enseignement supérieur et de la Recherche scientifique and the Ministère des Eaux et Forêts of Côte d'Ivoire, and the Office Ivoirien des Parcs et Réserves for permission to conduct this study. This project was funded by the University of California Santa Cruz and field work was supported by the Centre Suisse de Recherches Scientifiques en Côte d'Ivoire and its director Inza Koné.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Sample and data collection were conducted by V.M.O. and B.E.L., with logistical support of R.M.W. and J.P. Data analysis was performed by V.M.O. The manuscript was written by B.L. and V.M.O. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lowry, B.E., Wittig, R.M., Pittermann, J. et al. Stratigraphy of stable isotope ratios and leaf structure within an African rainforest canopy with implications for primate isotope ecology. Sci Rep 11, 14222 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93589-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-93589-8

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.