Abstract

Contrary to the early evidence, which indicated that the mitochondrial architecture in one of the two major annelida clades, Sedentaria, is relatively conserved, a handful of relatively recent studies found evidence that some species exhibit elevated rates of mitochondrial architecture evolution. We sequenced complete mitogenomes belonging to two congeneric shell-boring Spionidae species that cause considerable economic losses in the commercial marine mollusk aquaculture: Polydora brevipalpa and Polydora websteri. The two mitogenomes exhibited very similar architecture. In comparison to other sedentarians, they exhibited some standard features, including all genes encoded on the same strand, uncommon but not unique duplicated trnM gene, as well as a number of unique features. Their comparatively large size (17,673 bp) can be attributed to four non-coding regions larger than 500 bp. We identified an unusually large (putative) overlap of 14 bases between nad2 and cox1 genes in both species. Importantly, the two species exhibited completely rearranged gene orders in comparison to all other available mitogenomes. Along with Serpulidae and Sabellidae, Polydora is the third identified sedentarian lineage that exhibits disproportionally elevated rates of mitogenomic architecture rearrangements. Selection analyses indicate that these three lineages also exhibited relaxed purifying selection pressures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Metazoan mitochondrial genomes (mitogenomes) usually encode the set of 37 genes, comprising 2 rRNAs, 22 tRNAs, and 13 proteins, encoded on both genomic strands. Mitogenomic gene rearrangements can affect genome replication and transcription mechanisms, and produce disruptions in the gene expression co-regulation, so they should be strongly selected against1. Indeed, mitogenomic architecture is generally highly conserved2, but some unrelated lineages exhibit exponentially accelerated mitochondrial architecture rearrangement rates2,3,4,5,6,7,8.

The phylogeny of the phylum Annelida remains debated, but the latest review of its phylogeny proposed that the phylum is split into two major groups: Pleistoannelida, comprised of the subclasses Errantia and Sedentaria, and six ‘basal’ (early-branching) lineages: Sipuncula, Amphinomida, Chaetopteridae, Magelonidae, Oweniidae and Lobatocerebrum9. Unlike in other lophotrochozoan groups, the mitochondrial gene order (GO) in annelids long appeared to be relatively conserved, with an additional feature of all genes encoded on a single strand10. However, a more complex picture emerged during the last ten years. The early-branching lineages exhibit relatively high rearrangement rates11. Among the Errantia, species from the family Syllidae, several genera from the family Polynoidae, and genus Ophryotrocha exhibit relatively rapidly evolving mitochondrial architecture12,13,14. Among the Sedentaria, Urechis species exhibit somewhat rearranged GOs15, and species from families Sabellidae and Serpulidae exhibit highly rearranged GOs16,17,18.

The sedentarian family Spionidae (order Spionida) is one of the largest and most common polychaete families, whose members occur in a wide variety of benthic habitats. There is only one mitogenome belonging to this family available in the GenBank: Marenzelleria neglecta19. Moreover, this is the only mitogenome available in the GenBank for the entire nominal sedentarian order Spionida (the status of this order remains debated9). To address this dearth of data, and thereby improve our understanding of the dynamics of mitochondrial evolution in Sedentaria, we sequenced and characterised the entire mitogenomes of two congeneric Spionidae species: Polydora brevipalpa and Polydora websteri.

The spionid genus Polydora includes species that inhabit clastic sediments, shale rock, corraline algae, living coral, sponges, and mollusk shells. While most of the shell-boring polydorids do not cause harm to the host, a handful of species can cause considerable harm20. Polydora websteri Hartman in Loosanoff and Engle, 1943 is a highly invasive shell-boring species native to the Asian Pacific that nowadays occurs around the globe, mostly as a result of global trade of commercial oyster species21. It causes distress to the host, reduces their growth rates, makes them susceptible to parasites or diseases, and their presence (so-called ‘mud blisters’) lowers the market value of bivalves20. In this way, P. websteri causes considerable economic losses in commercial marine mollusk aquaculture globally21,22. The congeneric and morphologically similar Polydora brevipalpa Zachs, 1933 is a relatively poorly studied species with an apparently broad range throughout the North Pacific20. It primarily infests scallops (Pectinidae), and there is some evidence that it can also cause economic losses22,23. Therefore, apart from contributing to the understanding of evolutionary dynamics of the mitochondrial genome in Sedentaria, the sequencing of these two mitogenomes will also contribute useful data for future biogeographic and evolutionary studies of these two economically important polychaete species.

Results and discussion

Identity and phylogeny

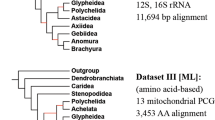

Morphological identification was successfully corroborated using DNA barcoding: P. brevipalpa and P. websteri barcode sequences (cox1 fragment) exhibited a similarity of 99.81% and 100% to the top conspecific barcode matches respectively. Several studies found that mitochondrial data produce artefactual relationships in annelids9,11, so we conducted only orientational phylogenetic analyses. As compositional heterogeneity in mitochondrial data can produce artefactual relationships in phylogenetic reconstruction24,25,26, first we tested the dataset for compositional homogeneity. All sequences included in the analysis failed the composition Chi-Square test (p-value < 5%; df = 3). Phylogenetic inference highly unorthodox relationships, with paraphyletic, Spionidae, Hirudinidae and Erpobdellidae (Supplementary File S1). Spionidae (represented by the two Polydora species and M. neglecta) were paraphyletic due to the unorthodox position of M. neglecta at the base of the Sedentaria. Sabellidae, Spionidae, and Serpulidae formed a clade, which is in disagreement with the accepted relationships of these families9.

Mitochondrial architecture

The mitogenomes of P. websteri and P. brevipalpa exhibited very similar architecture and identical sizes of 17,673 bp (Table 1). This is somewhat larger than common in sedentarians, which on average have mitogenomes of around 15 Kbp (Supplementary File S2: sheet A). Only 5 sedentarian mitogenomes were larger: Spirobranchus giganteus16, Siboglinium fiordicum29 and three Decemunciger sp. mitogenomes30 . Both Polydora species possess the standard set of 37 genes, plus a duplicated trnM gene copy between trnL1 and nad1 (Fig. 1). Duplicated trnM genes have been observed in a handful of annelid species before11,31. The two Polydora aside, six more species in our sedentarian dataset exhibited a duplicated trnM gene (as well as some species from the early-branching lineages) (Fig. 1). However, aside from the two Polydora species and S. giganteus, in all other species the two copies were adjacent (or very near each other). As common in annelids, all genes are encoded on the same strand. Palaeoannelida, Magelona mirabilis (Magelonidae), and S. spallanzanii (Sabellida) are the only annelids described so far with genes transcribed on both strands of the mitochondrial genome11,17. In terms of base composition, the two Polydora species (AT bias of 65–66%) are average among the Sedentaria (55–78%) (Supplementary File S2: sheet A).

Mitochondrial architecture in the studied annelid dataset. GenBank numbers of sequences are shown next to species' names. The two newly sequenced Polydora species are highlighted by the yellow background. Taxonomic identity is shown to the right at the family level. The colour legend for mitogenomic architecture is shown in the figure.

The two Polydora species exhibited more large noncoding regions (NCRs, four were larger than 150 bp) than most other species included in the analysis (Fig. 1). This was reflected in the relatively large noncoding/coding ratio of 17.2% in their mitogenomes (Supplementary File S2: sheet A). Only S. giganteus and three Decemunciger species exhibited comparable numbers of large NCRs. NCR-1, located between trnQ and trnA was the largest with over 1000 bp, but the remaining three were also very large: 535 to 661 bp (Table 1). This is the underlying reason for the comparatively large size of these two mitogenomes. Tandem-duplication-random-loss (TDRL) events were proposed as the most likely mechanism underlying the expansion of NCRs in S. giganteus16. Given the highly rearranged architecture of these two genomes, this may also be a likely explanation for their unusually high number of large NCRs, but this remains hypothetical due to absence of evidence. We attempted to align all four large NCRs against the entire mitogenome, but none of them exhibited a similarity to the nearby coding regions. This was expected, as non-coding mitochondrial sequences tend to evolve very rapidly due to strong mutation pressures32, and this architecture was shared by both species, which indicates that the four NCRs appeared in the common ancestor of these two species, or even the entire genus. We also examined all 4 NCRs for open-reading-frames (ORFs). NCR1 had 5 ORFs > 50 AAs, with one large ORF spanning most of the length of the NCR (349 AAs); NCR2 had 2 ORFs > 50 AAs (57 and 58); NCR3 had only 1 ORF > 50 AAs (145); and NCR4 had 2 ORFs > 50 AAs (187 and 182). However, BLASTp analysis did not find any similarity to known proteins for any of these putative protein products, so it is unlikely that these ORFs are functional proteins.

Mitochondrial genes of Annelids exhibit a rather large variability in size16. Most protein-coding genes (PCGs) of the two Polydora species were within the range observed in other Sedentaria (Supplementary File S2: sheet B), and the two species exhibited genes of very similar size (Table 1). A few outliers in terms of gene sizes among closely related species exhibited matching insertions/deletions in both Polydora species, which makes it very unlikely that these were sequencing or annotation artefacts. Cox2 was longer in these two species than in any other sedentarian mitogenome due to two insertions in the middle of the gene, and cytb was longer than in most other species due to an insertion at the 3’ end. The two species exhibited relatively similar start/stop codon usage (Table 1), comparable to other studied sedentarian species (Supplementary File S2: sheet B). Both species exhibited matching deletions at the 5’ end of cox1, which also explains the use of a different start codon (ATA) than in most other species (ATG).

On average, the most highly conserved sequences between the two genomes were exhibited by tRNA genes, only one of which (trnV) exhibited an identity value below 80% (Table 1). As common in mitochondrial genomes33, the most highly conserved PCGs were cox family genes, with identity values of 80–85%. Somewhat surprisingly, the nad gene family was the least conserved one, with identity values mostly between 74 and 76% (nad1 was an exception: 80%). Commonly, atp8 is the least conserved mitochondrial PCG2,33, but between these two species, it exhibited an identity of 75.84%, higher than most nad family genes. As expected, the fastest-evolving regions were NCRs, with identity values ranging from 53 to 70%.

Several genes exhibited overlaps in the two newly-sequenced mitogenomes. Genes overlapping by 1 or 2 bases have been observed in annelid mitogenomes34, but several overlaps in the two Polydora species were larger than 2 bp (Table 1). The relatively large overlap between atp8 and trnG (P. brevipalpa = 5 bp, P. websteri = 6 bp) can be explained by a 3’ end elongation of the atp8 gene of almost 20 bases. As the 5’ end of trnG is relatively conserved, this suggests that the overlap arose via a mutation that affected the stop codon of the atp8, and caused elongation to the nearest available stop codon (T–). As atp8 often evolves under relaxed selection constraints, it appears that this elongation did not significantly affect the fitness of the mutant phenotype. This is evidenced by both species exhibiting very similar features, which indicates that the event occurred in the common ancestor of these two species, or even the entire genus. For nad5 in P. websteri, we opted for an abbreviated T– stop codon, as this produces no overlap with the adjacent trnF (leaves 1 bp intergenic space between the two genes). An alternative option would be to elongate the gene by 11 bases, thus creating an overlap of 10 bases with trnF, and use the standard TAG stop codon. The codon alignment of the shorter gene (T– stop codon) with the P. brevipalpa orthologue does not indicate that the gene is truncated, so we chose this as a more likely option than a large overlap. The large overlap (14 bases) between nad2 and cox1 putatively identified in both species is highly unusual. Usually, overlaps in metazoan mitogenomes involve tRNA genes, which is considered to be a consequence of lesser evolutionary constraints on tRNA sequences35. The only common overlaps between two PCGs comprise atp6/atp8 and nad4/nad4L5,34,36,37,38,39,40, perhaps due to their translation from a bicistronic mRNA34,40. We checked DNA sequencing chromatograms for these (and all other large) overlaps and found no evidence of sequencing artefacts. An alternative option is that nad2 uses an abbreviated stop codon T–, which would produce a 1 bp intergenic region between the two genes in P. websteri, and 9 bp in P. brevipalpa. However, abbreviated codons are usually associated with overlaps with tRNAs41,42,43, and not conserved between the two species. Given these problems, we deem the overlap to be a more likely option, but transcriptome analyses are needed to confirm this prediction.

Gene order rearrangements

The two newly sequenced Polydora species exhibited completely rearranged GOs in comparison to all other available mitogenomes (Fig. 1, Table 2). Generally, GO rearrangements involving the relatively volatile tRNA genes are much more common than relatively rare PCG rearrangements2, but the order of PCGs was also highly rearranged in these two mitogenomes. Aside from the conserved sedentarian gene order exhibited by a majority of species (Common GO), there were 23 unique GOs in the dataset (among 97 mitogenomes). Three lineages exhibit by far the most highly rearranged GOs in comparison to the common GO: Serpulidae (represented by S. giganteus and Hydroides norvegica), S. spallanzanii (Sabellidae), and the two Polydora species. The common intervals similarity measure (where the value 1326 indicates an identical GO, and 0 indicates no shared common intervals) indicates that S. giganteus had the most rearranged GO (0), followed by S. spallanzanii (4), H. norvegica (6), and the two Polydora species (12) (Table 2). All other species exhibited much higher similarity values (≥ 90). The only other available Spionidae species, M. neglecta, also exhibited a unique GO, but much less rearranged than the two Polydora species (320). CREx analysis indicates that at least five TDRL events were necessary to explain the evolution from the common GO to the one observed in the two newly sequenced Polydora species (Supplementary File S3: Figure S1). The same number of TDRL events was inferred for S. giganteus and H. norvegica, but S. spallanzanii required a much more complex scenario (Supplementary File S3: Figures S2–S4).

If mitogenomic architecture rearrangements are strongly selected against1, it would be expected that elevated rearrangement rate would be associated with relaxed purifying selection pressure, which in turn should be reflected on the molecular evolution rate. To test this hypothesis, we used RELAX tool and concatenated 13 PCGs (nucleotide sequences). With all sedentarian species (and Polydora node) in the dataset selected as test branches (exploratory mode), the Polydora branch (representing the common ancestor of the two sequenced Polydora species) exhibited somewhat relaxed purifying selection (but not exceptional in the sedentarian dataset): k = 0.63 (where k > 1 intensified, k < 1 relaxed selection). However, the two Polydora species themselves exhibited highly intensified selection (k ≈ 15–17). Following this, we conducted the analysis with most species set as the reference dataset, and only the species exhibiting elevated rates of architecture rearrangements as test branches: the two Polydora species, Polydora branch, S. spallanzanii, H. norvegica and S. giganteus. This test for selection relaxation was significant (p = 0.00). The Polydora branch exhibited a highly relaxed purifying selection within the dataset (0.33), but the two Polydora species still exhibited intensified selection pressures (P. websteri k = 19.60, P. brevipalpa k = 18.77). The remaining three species exhibited relaxed selection pressures: S. spallanzanii k = 0.44, H. norvegica = 0.45 and S. giganteus k = 0.45. This corroborates that there is an association between the mitochondrial architecture rearrangement rate and purifying selection pressure in sedentarians, but the signal from Polydora species is rather puzzling and requires further studies.

Conclusions

Among the Sedentaria, three lineages exhibit disproportionally highly elevated rates of mitogenomic architecture rearrangements: Serpulidae (represented by S. giganteus16 and H. norvegica18), S. spallanzanii (Sabellidae)17, and the two newly sequenced Polydora mitogenomes. Whereas all available Serpulidae and Sabellidae species exhibit a highly elevated mitochondrial architecture evolution rate, among the Spionidae this is limited to the genus Polydora. The other available species, M. neglecta, exhibits only a moderate gene order rearrangement rate. Intriguingly, species from these lineages formed a paraphyletic clade in phylogenetic analysis, which is most likely to be a classical example of a long-branch attraction artefact28. Indeed, it was previously observed that S. giganteus s exhibits a highly elevated evolutionary rate16, and proposed that this may be causing artefactual relationships in phylogenetic analyses27. Due to scarcity of data, the exact phylogenetic scope, and the underlying reason for, these elevated evolutionary rates remains unknown. This further supports previous observations that mitochondrial architecture is not fully conserved among the Sedentaria16,17,18, and indirectly corroborates the proposal that the evolution of mitogenomic architecture is highly discontinuous: long periods of stasis are interspersed with periods of exponentially accelerated evolutionary rate of mitogenomic rearrangements5. The previous observation that S. spallanzanii has genes encoded on both mitochondrial strands raises intriguing questions about the evolution of mitochondrial transcription mechanism in Annelida11, as Boore proposed a ‘ratchet’ effect that would constitute a barrier to further strand switches once the replication mechanism has been lost on one strand40. As introns were described in mitochondrial genes of three separate annelid lineages so far30,44,45, this implies that mitochondrial evolution in Sedentaria deserves more scientific attention than it is currently receiving and that further annelid mitogenomes should be sequenced in order to further elucidate the intriguing patterns of mitogenomic evolution in this class.

Methods

Sample, sequencing, assembly and annotation

Samples used for sequencing were procured at two different locations (Table 3). Samples were identified morphologically according to20 and more recent redescriptions23,46, as well as via cox1 barcoding using the BOLD database47. As the animal handling included only unprotected invertebrates, no special permits were required to retrieve and process the samples.

DNA extraction, amplification, sequencing and mitogenome assembly were conducted closely following the methodology described before6,48. Briefly, DNA was extracted from the complete specimens using AidLab DNA extraction kit (AidLab Biotechnologies, Beijing, China). The mitogenomes were amplified and sequenced using 14 and 12 primer pairs, respectively (Supplementary File S3: Tables S1 and S2). The primers were designed to produce amplicons that overlap by approximately 100 bp. PCR reaction mixture of 50 µL comprised 5 U/µL of TaKaRa LA Taq polymerase (TaKaRa, Japan), 10 × LATaq Buffer II, 2.5 µM of dNTP mixture, 0.2–1.0 µM of each primer, and 60 ng of DNA template. PCR conditions were: initial denaturation at 98 °C for 2 min, and 40 cycles of 98 °C for 10 s, 50 °C for 15 s, and 68 °C for 1 min/kb. PCR products were sequenced using the same set of primers and Sanger method. Electropherograms were visually inspected, and amplicon identity was confirmed using BLAST49. The mitogenomes were assembled using DNAstar v7.150, making sure that overlaps were identical and mitogenomes circular. Protein-coding genes were approximately located using DNAstar and then manually checked against the orthologous sequences using BLAST and BLASTx. tRNAs were identified using tRNAscan51 and ARWEN52 tools. The two ribosomal RNAs were manually annotated via a comparison with orthologues. The mitogenome of Marenzelleria neglecta19, the only available Spionidae representative, was used as the template for assembly and annotation. The annotation recorded in a Word (Microsoft Office) document was parsed and extracted using PhyloSuite53. The same program was used to generate the file for submission to GenBank.

Dataset, comparative mitogenomic, phylogenetic, sequence and selection analyses

We used PhyloSuite53 to retrieve, standardize, and extract features of mitogenomes available in the GenBank; as well as standardise the annotation (gene names), semi-automatically re-annotate ambiguously annotated tRNA genes with the help of the ARWEN output, extract mitogenomic features, generate comparative tables, concatenate alignments and prepare input files for its plug-in programs. We conducted analyses on all Sedentaria (sensu9) mitogenomes available in the GenBank. We included two Errantia (Nereididae) species as outgroups: Platynereis dumerilii54 and Neanthes glandicincta55. A study has shown that mitochondrial data produce phylogenetic artefacts when incomplete mitogenomes are included in analysis11, so we removed seven mitogenomes that exhibited missing PCGs (small genes, like atp8, were ignored in this case). All phylogenetic analysis steps were conducted using PhyloSuite and its plug-in programs. Amino acid sequences of 13 PCGs were aligned in batches using the accurate 'G-INS-i strategy implemented in MAFFT56. Maximum likelihood phylogeny was inferred using IQ-TREE57, with 20,000 ultrafast bootstraps58. This program uses ModelFinder59 for the optimal model selection, and phylogenetic terrace aware data structure for the efficient analysis under partition models60. Phylograms and gene orders were visualized and annotated (using files generated by PhyloSuite) in iTOL61. MEGA-X62 was used to attempt to align NCR sequences to the rest of the mitogenomes, and ORFfinder63 was used to search for ORFs in the NCRs. CREX was used to infer the GO distances64. RELAX, available from the Datamonkey server65, was used to test whether the strength of natural selection has been statistically significantly relaxed or intensified along a specified set of test branches66. We used concatenated nucleotide sequences of 13 PCGs for this analysis.

Ethics declaration

As the animal handling included only unprotected invertebrates, no special permits were required to retrieve and process the samples.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article, its supplementary information files, and the NCBI’s GenBank repository under the accession numbers MW316633 (P. websteri) and MW316635 (P. brevipalpa).

Abbreviations

- NCR:

-

Non-coding region

- PCG:

-

Protein-coding gene

References

Boore, J. L. The Duplication/Random Loss Model for Gene Rearrangement Exemplified by Mitochondrial Genomes of Deuterostome Animals 133–147 (Springer, Berlin, 2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-4309-7_13.

Gissi, C., Iannelli, F. & Pesole, G. Evolution of the mitochondrial genome of Metazoa as exemplified by comparison of congeneric species. Heredity 101, 301–320 (2008).

Moritz, C. & Brown, W. M. Tandem duplications in animal mitochondrial DNAs: Variation in incidence and gene content among lizards. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84, 7183–7187 (1987).

Gissi, C. et al. Hypervariability of ascidian mitochondrial gene order: Exposing the myth of deuterostome organelle genome stability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 27, 211–215 (2010).

Zou, H. et al. The complete mitochondrial genome of parasitic nematode Camallanus cotti: Extreme discontinuity in the rate of mitogenomic architecture evolution within the Chromadorea class. BMC Genom. 18, 840 (2017).

Zou, H. et al. Architectural instability, inverted skews and mitochondrial phylogenomics of Isopoda: outgroup choice affects the long-branch attraction artefacts. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 191887 (2020).

Fujita, M. K., Boore, J. L. & Moritz, C. Multiple origins and rapid evolution of duplicated mitochondrial genes in parthenogenetic geckos (Heteronotia binoei; Squamata, Gekkonidae). Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 2775–2786 (2007).

Bernt, M. et al. A comprehensive analysis of bilaterian mitochondrial genomes and phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 352–364 (2013).

Weigert, A. & Bleidorn, C. Current status of annelid phylogeny. Org. Divers. Evol. 16, 345–362 (2016).

Jennings, R. M. & Halanych, K. M. Mitochondrial genomes of Clymenella torquata (Maldanidae) and Riftia pachyptila (Siboglinidae): Evidence for conserved gene order in Annelida. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 210–222 (2005).

Weigert, A. et al. Evolution of mitochondrial gene order in Annelida. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 94, 196–206 (2016).

Aguado, M. T. et al. Syllidae mitochondrial gene order is unusually variable for Annelida. Gene 594, 89–96 (2016).

Tempestini, A. et al. Extensive gene rearrangements in the mitogenomes of congeneric annelid species and insights on the evolutionary history of the genus Ophryotrocha. BMC Genom. 21, 815 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Phylogeny, evolution and mitochondrial gene order rearrangement in scale worms (Aphroditiformia, Annelida). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 125, 220–231 (2018).

Golombek, A., Tobergte, S., Nesnidal, M. P., Purschke, G. & Struck, T. H. Mitochondrial genomes to the rescue: Diurodrilidae in the myzostomid trap. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 68, 312–326 (2013).

Seixas, V. C., Russo, C. A. D. M. & Paiva, P. C. Mitochondrial genome of the Christmas tree worm Spirobranchus giganteus (Annelida: Serpulidae) reveals a high substitution rate among annelids. Gene 605, 43–53 (2017).

Daffe, G., Sun, Y., Ahyong, S. T. & Kupriyanova, E. K. Mitochondrial genome of Sabella spallanzanii (Gmelin, 1791) (Sabellida: Sabellidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 6, 499–501 (2021).

Sun, Y. et al. Another blow to the conserved gene order in Annelida: Evidence from mitochondrial genomes of the calcareous tubeworm genus Hydroides. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 160, 107124 (2021).

Gastineau, R., Wawrzyniak-Wydrowska, B., Lemieux, C., Turmel, M. & Witkowski, A. Complete mitogenome of a Baltic Sea specimen of the non-indigenous polychaete Marenzelleria neglecta. Mitochondrial DNA Part B 4, 581–582 (2019).

Blake, J. A. Family Spionidae Grube, 1850. In Taxonomic Atlas of the Benthic Fauna of the Santa Maria Basin and Western Santa Barbara Channel, Vol. 6 The Annelida Part 3-Poly vol. 6 81–224 (Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, 1996).

Waser, A. M. et al. Spread of the invasive shell-boring annelid Polydora websteri (Polychaeta, Spionidae) into naturalised oyster reefs in the European Wadden Sea. Mar. Biodivers. 50, 63 (2020).

Sato-Okoshi, W., Okoshi, K., Abe, H. & Li, J.-Y. Polydorid species (Polychaeta, Spionidae) associated with commercially important mollusk shells from eastern China. Aquaculture 406–407, 153–159 (2013).

Ye, L., Yao, T., Wu, L., Lu, J. & Wang, J. Morphological and molecular diagnoses of Polydora brevipalpa Zachs, 1933 (Annelida: Spionidae) from the shellfish along the coast of China. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 37, 713–723 (2019).

Zhang, D. et al. Mitochondrial architecture rearrangements produce asymmetrical nonadaptive mutational pressures that subvert the phylogenetic reconstruction in isopoda. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 1797–1812 (2019).

Rubinoff, D., Holland, B. S. & Savolainen, V. Between two extremes: Mitochondrial DNA is neither the panacea nor the nemesis of phylogenetic and taxonomic inference. Syst. Biol. 54, 952–961 (2005).

Yang, H., Li, T., Dang, K. & Bu, W. Compositional and mutational rate heterogeneity in mitochondrial genomes and its effect on the phylogenetic inferences of Cimicomorpha (Hemiptera: Heteroptera). BMC Genomics 19, 264 (2018).

Tilic, E., Atkinson, S. D. & Rouse, G. W. Mitochondrial genome of the freshwater annelid Manayunkia occidentalis (Sabellida: Fabriciidae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 5, 3313–3315 (2020).

Lartillot, N., Brinkmann, H. & Philippe, H. Suppression of long-branch attraction artefacts in the animal phylogeny using a site-heterogeneous model. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, S4 (2007).

Li, Y. et al. Mitogenomics reveals phylogeny and repeated motifs in control regions of the deep-sea family Siboglinidae (Annelida). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 85, 221–229 (2015).

Bernardino, A. F., Li, Y., Smith, C. R. & Halanych, K. M. Multiple introns in a deep-sea Annelid ( Decemunciger: Ampharetidae) mitochondrial genome. Sci. Rep. 7, 4295 (2017).

Zhong, M., Struck, T. H. & Halanych, K. M. Phylogenetic information from three mitochondrial genomes of Terebelliformia (Annelida) worms and duplication of the methionine tRNA. Gene 416, 11–21 (2008).

Reyes, A., Gissi, C., Pesole, G. & Saccone, C. Asymmetrical directional mutation pressure in the mitochondrial genome of mammals. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 957–966 (1998).

Castellana, S., Vicario, S. & Saccone, C. Evolutionary patterns of the mitochondrial genome in Metazoa: Exploring the role of mutation and selection in mitochondrial protein-coding genes. Genome Biol. Evol. 3, 1067–1079 (2011).

Boore, J. L. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the polychaete annelid Platynereis dumerilii. Mol. Biol. Evol. 18, 1413–1416 (2001).

Doublet, V. et al. Large gene overlaps and tRNA processing in the compact mitochondrial genome of the crustacean Armadillidium vulgare. RNA Biol. 12, 1159–1168 (2015).

Wen, H. B. et al. The complete maternally and paternally inherited mitochondrial genomes of a freshwater mussel Potamilus alatus (Bivalvia: Unionidae). PLoS ONE 12, e0169749 (2017).

Wang, J.-G. et al. Sequencing of the complete mitochondrial genomes of eight freshwater snail species exposes pervasive paraphyly within the Viviparidae family (Caenogastropoda). PLoS ONE 12, e0181699 (2017).

Liu, F.-F., Li, Y.-P., Jakovlić, I. & Yuan, X.-Q. Tandem duplication of two tRNA genes in the mitochondrial genome of Tagiades vajuna (Lepidoptera: Hesperiidae). EJE 114, 407–415 (2017).

Zhang, D. et al. Sequencing of the complete mitochondrial genome of a fish-parasitic flatworm Paratetraonchoides inermis (Platyhelminthes: Monogenea): tRNA gene arrangement reshuffling and implications for phylogeny. Parasit. Vectors 10, 462 (2017).

Boore, J. L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 1767–1780 (1999).

Montagna, M. et al. Tick-box for 3′-end formation of mitochondrial transcripts in ixodida, basal chelicerates and drosophila. PLoS ONE 7, e47538 (2012).

Ojala, D., Montoya, J. & Attardi, G. tRNA punctuation model of RNA processing in human mitochondria. Nature 290, 470–474 (1981).

Berthier, F., Renaud, M., Alziari, S. & Durand, R. RNA mapping on Drosophila mitochondrial DNA: Precursors and template strands. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 4519 (1986).

Vallès, Y., Halanych, K. M. & Boore, J. L. Group II introns break new boundaries: Presence in a Bilaterian’s genome. PLoS ONE 3, e1488 (2008).

Richter, S., Schwarz, F., Hering, L., Böggemann, M. & Bleidorn, C. The utility of genome skimming for phylogenomic analyses as demonstrated for glycerid relationships (Annelida, Glyceridae). Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 3443–3462 (2015).

Ye, L. et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of Polydora websteri (Annelida: Spionidae), with remarks on relationship of adult worms and larvae using mitochondrial COI gene as a molecular marker. PJZ 49, 699–710 (2017).

Ratnasingham, S. & Hebert, P. D. N. Bold: The barcode of life data system (http://www.barcodinglife.org). Mol. Ecol. Notes 7, 355–364 (2007).

Zhang, D. et al. Three new Diplozoidae mitogenomes expose unusual compositional biases within the Monogenea class: Implications for phylogenetic studies. BMC Evol. Biol. 18, 133 (2018).

Altschul, S. F. et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402 (1997).

Burland, T. G. DNASTAR’s Lasergene sequence analysis software. In Methods in Molecular BiologyTM Vol. 132 (eds Misener, S. & Krawetz, S. A.) 71–91 (Humana Press, Totowa, 2000).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–W689 (2005).

Laslett, D. & Canbäck, B. ARWEN: A program to detect tRNA genes in metazoan mitochondrial nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 24, 172–175 (2008).

Zhang, D. et al. PhyloSuite: an integrated and scalable desktop platform for streamlined molecular sequence data management and evolutionary phylogenetics studies. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 20, 348–355 (2020).

Boore, J. L. & Brown, W. M. Mitochondrial genomes of galathealinum, helobdella, and platynereis: Sequence and gene arrangement comparisons indicate that pogonophora is not a phylum and annelida and arthropoda are not sister taxa. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 87–106 (2000).

Lin, G.-M., Audira, G. & Hsiao, C.-D. The complete mitogenome of nereid worm, Neanthes glandicincta (Annelida: Nereididae). Mitochondrial DNA Part B 2, 471–472 (2017).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Nguyen, L.-T., Schmidt, H. A., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015).

Minh, B. Q., Nguyen, M. A. T. & von Haeseler, A. Ultrafast approximation for phylogenetic bootstrap. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1188–1195 (2013).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S., Minh, B. Q., Wong, T. K. F., Von Haeseler, A. & Jermiin, L. S. ModelFinder: Fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A. & Minh, B. Q. Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Syst. Biol. 65, 997–1008 (2016).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23, 127–128 (2007).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C. & Tamura, K. MEGA X: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 1547–1549 (2018).

Wheeler, D. L. et al. Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, D5–D12 (2007).

Bernt, M. et al. CREx: Inferring genomic rearrangements based on common intervals. Bioinformatics 23, 2957–2958 (2007).

Weaver, S. et al. Datamonkey 2.0: A modern web application for characterizing selective and other evolutionary processes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 773–777 (2018).

Wertheim, J. O., Murrell, B., Smith, M. D., Kosakovsky Pond, S. L. & Scheffler, K. RELAX: Detecting relaxed selection in a phylogenetic framework. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 820–832 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We want to express our sincere thanks to Professor Zhongming Huo from Dalian Ocean University for his help in polydorid sample collection, and to anonymous reviewers whose comments helped us improve the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFD0900105), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2018A030313349), the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, CAFS (2020TD42, 2021SD05), the Shellfish and Large Algae Industry Innovation Team Project of Guangdong Province (2021KJ146), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, the Professorial and Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Huizhou University, the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (202002030488), and Guangdong Rural Revitalization Strategy Special Funds (Fishery Industry Development) (YueCaiNong[2020]4).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. conceived the study. J.L., T.Y. and C.B. collected samples and conducted data analyses. L.Y., T.Y. and J.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, L., Yao, T., Lu, J. et al. Mitochondrial genomes of two Polydora (Spionidae) species provide further evidence that mitochondrial architecture in the Sedentaria (Annelida) is not conserved. Sci Rep 11, 13552 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92994-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-92994-3

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.