Abstract

Thienamycin, the first representative of carbapenem antibiotics was discovered in the mid-1970s from soil microorganism, Streptomyces cattleya, during the race to discover inhibitors of bacterial peptidoglycan synthesis. Chemically modified into imipenem (N-formimidoyl thienamycin), now one of the most clinically important antibiotics, thienamycin is encoded by a thienamycin gene cluster composed of 22 genes (thnA to thnV) from S. cattleya NRRL 8057 genome. Interestingly, the role of all thn-genes has been experimentally demonstrated in the thienamycin biosynthesis, except thnS, despite its annotation as putative β-lactamase. Here, we expressed thnS gene and investigated its activities against various substrates. Our analyses revealed that ThnS belonged to the superfamily of metallo-β-lactamase fold proteins. Compared to known β-lactamases such as OXA-48 and NDM-1, ThnS exhibited a lower affinity and less efficiency toward penicillin G and cefotaxime, while imipenem is more actively hydrolysed. Moreover, like most MBL fold enzymes, additional enzymatic activities of ThnS were detected such as hydrolysis of ascorbic acid, single strand DNA, and ribosomal RNA. ThnS appears as a MBL enzyme with multiple activities including a specialised β-lactamase activity toward imipenem. Thus, like toxin/antitoxin systems, the role of thnS gene within the thienamycin gene cluster appears as an antidote against the produced thienamycin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bioactive compounds such as secondary metabolites are biosynthesised by non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and polyketide synthases (PKS), enzymes that have been identified in the different domains of life with an extraordinary diversity and more than 3,300 NRPS/PKS have been reported from 991 different organisms1. These bioactive compounds exhibiting a wide range of biological activities can include siderophores, pigments, cytostatics, immunosuppressants, toxins, and antibiotics2,3. Toxins or natural antibiotics are expressed by some microorganisms (e.g. fungus and/or bacteria) to master their ecosystems4. According to the mode of action, antibiotics can be classified into several groups including synthesis inhibitors of cell walls, proteins, DNA, RNA, and others5. Most antibiotic classes including aminoglycosides, macrolides, tetracyclines, chloramphenicol, and β-lactams have been synthesised by biosynthesis gene clusters identified in Actinobacteria such as Nocardia, Saccharopolyspora, Kitasatospora, or Streptomyces5. Furthermore, some β-lactams, especially carbapenem antibiotics, can be synthesised by more common bacteria such as Enterobacterial phytopathogens, including Serratia sp. or Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica (now renamed Pectobacterium carotovora subsp. atroseptica), or Photorhabdus luminescens6,7. Like toxin-antitoxin systems, these microorganisms develop self-resistance mechanisms to protect themselves against attacks from their own biosynthetic bioactive compounds5,8. These self-resistance mechanisms such as antibiotic efflux pumps, antibiotic-modifying enzymes, or antibiotic-hydrolysing enzymes are often encoded by genes located within the biosynthesis gene clusters5. Among these antibiotics, thienamycin, the first to be discovered and characterised as a carbapenem and one of the most clinically important antibiotic classes, is encoded by a thienamycin gene cluster (TGC) composed of 22 genes (thnA to thnV) from Streptomyces cattleya NRRL 8057 genome9,10. In addition to thienamycin, another antibiotic. cephamycin (cephalosporin sub-class) encoded by a cephamycin gene cluster (CGC) (composed of 16 genes), has been also identified within the same S. cattleya NRRL 8057 genome10. However, while the role of almost all genes of the TGC have been experimentally well characterised in thienamycin biosynthesis11,12, the role and function of the thnS gene, despite its annotation as putative β-lactamase, remain unreported and it was suggested this should be clarified12. Here, we investigate the phylogenetic relationship of the ThnS enzyme with bacterial β-lactamase enzymes and explore its enzymatic activity against different substrates including antibiotic drugs, ascorbic acid, DNA, and RNA substrates.

Results

Origins of ThnS enzyme

The thnS gene is part of the thienamycin gene cluster (TGC) located on the linear megaplasmid (pSCAT, 1′809′491-bp, 73.21%CG) of the S. cattleya NRRL 8057 genome. As shown in Fig. 1, the TGC, with size of 28.25-Kb and %GC content of 73.61%, is composed of 22 genes in which thnI and thnU encode for the transcriptional activators of expression of the thnH, J, K, L, M, N, O, P, and Q genes, while the expression of the remaining genes (thnA-G, thnR-V) are thnIU-independent12. BlastP analysis of the ThnS sequence against the NCBI database reveals the best homologous sequences (coverage ≥ 50% and similarity ≥ 84%) with metallo-β-lactamase (MBL), fold metallo-hydrolase and the L-ascorbate metabolism protein UlaG, all identified from the Pseudonocardiaceae family. Its best homologous sequences within more common bacteria, especially Enterobacteriaceae species, are also all annotated as MBL fold metallo-hydrolase with homologies ranging from 27% coverage and 34% identity with Serratia ficaria and 79% coverage and 24.15% identity with Escherichia coli (Suppl. Table S1).

Phylogenetic relationship of the ThnS enzyme with bacterial β-lactamases

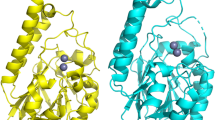

The inferred phylogenetic tree of the ThnS sequence with the four bacterial classes of β-lactamases (A, B, C, and D) shows that the ThnS enzyme is closely related to the bacterial class B β-lactamases (Fig. 2A). This membership is confirmed by sequence alignment with the three sub-classes (B1, B2, B3) highlighting the conserved “HxHxDH” motif and H196, H263 residues, that are specific to this metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) superfamily group (Fig. 2B). Moreover, three-dimensional (3D) structural analysis of the ThnS protein model from the Phyre2 investigator database confirms with 100% confidence and more than 81% coverage that ThnS was similar to the crystal structure of an uncharacterised metallo protein from Vibrio cholerae with β-lactamase-like fold (Phyre2 ID: c3bv6D; Uniprot ID: Q9KMS2).

Phylogenetic relationship of ThnS with bacterial β-lactamases. (A) phylogenetic tree analysis of the ThnS protein with described bacterial β-lactamase sequences; (B) protein alignment of ThnS with class B β-lactamase sequences exhibiting the conserved motif and residues of this class. The phylogenetic tree was inferred using the maximum-likelihood method in FastTree then displayed using the FigTree software v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

β-lactam-hydrolysing activity

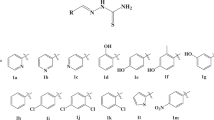

To evaluate the enzymatic activity of ThnS, this latter and two bacterial β-lactamases including class D OXA-48 and class B NDM-1 carbapenemases were expressed and tested against different antibiotic substrates including nitrocefin, penicillin G, cefotaxime, and imipenem. Interestingly, ThnS was unable to hydrolyze the nitrocefin substrate while both bacterial β-lactamases (OXA-48 and NDM-1) significantly hydrolyse this substrate (data not shown). However, as presented in Fig. 3A,B, the ThnS enzyme degrades penicillin G, as observed for OXA-48 and NDM-1 enzymes, but more slowly during the 24 h test, suggesting a lower affinity toward penicillin G. Regarding imipenem hydrolysis, the ThnS activity was comparable with both OXA-48 and NDM-1 carbapenemases (Fig. 3C). ThnS here appears to be more active against this drug since the measured amount of imipenem metabolite (imipenemoic acid) after 24 h of incubation was higher for ThnS compared to the two enzyme controls (Fig. 3D). Compared to both bacterial β-lactamases, the hydrolysis of cefotaxime by ThnS was detected only after 24 h and appears then less active against this cephalosporin compared to the enzyme controls, also suggestive of a lower affinity toward cephalosporin antibiotic (Fig. 3E).

Monitoring the degradation of β-lactam drugs by the expressed ThnS enzyme compared to known bacterial β-lactamases (OXA-48 and NDM-1). (A) detection of Penicillin G over 24 h in presence or absence of the tested enzymes; (B) detection of the penicillin G metabolite (benzyl penilloic acid) when Penicillin G is incubated with the tested enzymes over 24 h; (C) monitoring the amount of imipenem when incubated with the tested enzymes over 24 h; (D) monitoring the amount of imipenem metabolite (imipenemoic acid) when imipenem is incubated with the tested enzymes over 24 h; (E) monitoring the amount of cefotaxime when incubated with the tested enzymes over 24 h.

Degradation activity on ascorbic acid

Based on BlastP analyses (presented above), the ThnS enzyme exhibited significant homology with UlaG, a manganese-dependent metallo-β-lactamase enzyme involved in L-ascorbate metabolism through the degradation of ascorbic acid13. Interestingly, it has been suggested that the UlaG precursor shared the RNA metabolising function with the last common ancestor enzyme and its descendants have a wide functional activities and phylogenetic distribution13. Figure 4A, ThnS enzyme shows 3D structure similarity with UlaG protein from E. coli and the same amino acid residues in their catalytic site (Fig. 4B). Thus, based on similarity of protein sequence and 3D structure with UlaG enzymes, ThnS activity against ascorbic acid was tested and monitored by LC–MS. As expected, compared to the control enzyme (OXA-48), ThnS significantly degrades ascorbic acid substrate after two hours of incubation, and after four hours the substrate was no longer detected (Fig. 4C).

3D model of the ThnS enzyme and monitoring ascorbic acid degradation by ThnS. (A) 3D structure comparison of the ThnS Phyre2 model and the UlaG structure (PDB: 2WYM); (B) 3D model of ThnS showing common residues in the catalytic site with the UlaG enzyme; structure alignment and visualisation were performed using the PyMOL 1.8.6.0 software (https://github.com/schrodinger/pymol-open-source). (C) monitoring ascorbic acid degradation by ThnS using LC–MS. OXA-48 carbapenemase enzyme is used here as a negative enzyme control.

Nuclease and ribonuclease activity

Previously reported in the literature, MBL fold proteins can exhibit different promiscuous enzymatic activities such as nuclease and/or ribonuclease activity14,15. Here, in addition to the detected β-lactam-hydrolysing and ascorbic acid degradation activities of this enzyme, its nuclease and ribonuclease activities were investigated. Interestingly, after two hours incubating ThnS with extracted E. coli RNA, the extracted E. coli RNA was specifically and completely hydrolysed in the presence or absence of a metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor (i.e., chelating EDTA agent) while using negative control enzyme (Glycine oxidase) did not (Fig. 5A). Moreover, synthetic single and double-stranded DNA was incubated with ThnS to evaluate its DNAse activity. Interestingly, while the double-stranded DNA was not affected by the ThnS enzyme (Fig. 5B) as observed for the positive control enzyme used (bacterial DNAse), both forward single DNA (ssDNA Fwd)(Fig. 5C) and reversed single DNA (ssDNA Rev)(Fig. 5D) were degraded by ThnS and the tested metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor did not affect its nuclease activity. As expected, the negative control enzyme (GO) showed no DNAse activity.

Nuclease and ribonuclease activities of the purified ThnS enzyme. (A) Degradation of bacterial total RNAs by the ThnS enzyme in the presence and absence of metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor (EDTA). GO (Glycine Oxidase) is used here as negative control enzyme; (B) Nuclease activity of ThnS on dsDNA; (C) Nuclease activity of ThnS on forward ssDNA ; (D) Nuclease activity of ThnS on reverse ssDNA. The ThnS activity was tested in the presence and absence of a metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor (EDTA). Glycine Oxidase (GO) and DNAse enzymes were used here as negative and positive controls, respectively. “Blank” refers to the empty vector eluted under the same conditions as that of the expressed ThnS enzyme.

Discussion

Natural β-lactam antibiotics such as penicillin, cephalosporin C, or thienamycin6,16 are expressed as poisons in the ancestral battle of microorganisms to colonise and master their ecosystems. In this context, β-lactamase enzymes appeared as antidotes to β-lactams produced by bacteria for their self-protection against these bioactive compounds. This suggest that like toxin/antitoxin systems, genes encoding for β-lactams and β-lactamases have always co-evolved within the NRPS/PKS clusters in microorganisms and we can speculate that the human massive use and misuse of antibiotics such as β-lactams during the last century has changed this co-evolution, leading to need for bacteria to acquired β-lactamases. Resistance to carbapenems, especially to imipenem, the N-formimidoyl derivative of thienamycin, now represents one of the biggest concerns in treating infections caused by multidrug resistant bacteria17. In this study, we showed that the thnS gene, part of the thienamycin gene cluster responsible for the biosynthesis and expression of the thienamycin drug by the S. cattleya NRRL8057 isolate11, is closely related to bacterial class B MBL enzymes. We demonstrated a β-lactam-hydrolysing activity of the ThnS enzyme and, interestingly, a specific and more efficient activity against imipenem. So, the presence of the thnS gene in this thienamycin gene cluster, demonstrates its antidote role toward the produced thienamycin poison. According to this finding, it is predictable to find that bacteria producing antibiotics from the NRPS/PKS clusters, may harbour within these clusters an antidote protein co-expressed with the bioactive poison. In fact, in addition to this poison/antidote system (i.e., thienamycin/ThnS β-lactamase) within the S. cattleya NRRL8057 genome, another biosynthesis gene cluster, the cephamycin gene cluster (CGC), responsible for the synthesis of isopenicillin N and cephamycin antibiotics, has been described in this bacterium10 and near the CGC, a Class A-like β-lactamase gene (cphB), phylogenetically related to extended-spectrum-β-lactamase (ESBL) can be identified (Suppl. fig. S1). In other bacterial pathogens such as Erwinia carotovora, a producer of carbapenem antibiotic from a “Car” antibiotic biosynthesis gene cluster in its genome, a same poison/antidote system has been identified in which the antidote proteins correspond to an operon carFG encoding for an efflux pump, conferring an intrinsic resistance mechanism12. The same CarFG-like efflux pump has also been identified in two Serratia, located within the antibiotic biosynthesis gene cluster12. In conclusion, the ThnS enzyme appears as a class B metallo-β-lactamase enzyme with an essential antidote role for S. cattleya bacterium toward its biosynthesised thienamycin poison.

Materials and methods

Phylogeny of the ThnS protein

To investigate the phylogenetic relationship of the ThnS protein from the Streptomyces cattleya NRRL8057 genome with known bacterial β-lactamases, representative protein sequences of the four described β-lactamase classes (i.e. A, B, C, and D) were retrieved from the ARG-ANNOT database18 and pooled together to infer a phylogenetic tree. Moreover, some DD-peptidase sequences, more related to class C β-lactamase were retrieved from the NCBI database and included in the phylogenetic tree analysis. All protein sequences were aligned using Mafft19; gaps within alignment were removed using Trimal20 and the phylogenetic tree was inferred using the maximum-likelihood method in FastTree21, then displayed using the FigTree software v1.4.4 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/).

Recombinant protein expression and purification

The whole tested protein including peptide signals of ThnS, NDM-1 (Ac. n° HQ328085), and OXA-48 (Ac. n° QSS32949.1) were designed to include a Strep-tag at the N-terminus and the corresponding nucleic acid sequence were optimised for expression in Escherichia coli. Its corresponding genes were synthetised by GenScript (Piscataway, NJ, USA) and ligated between the NdeI and NotI restriction sites of a pET24a( +) plasmid. E. coli BL21(DE3)-pGro7/GroEL (Takara, Kyoto, Japan), grown in ZYP-5052 media were used for the expression of the recombinant protein. When the culture reached an OD600 nm = 0.6 at 37 °C, the temperature was decreased to 20 °C and L-arabinose (0.2% m/v) was added in order to induce the expression of chaperones. As we previously reported, after 20 h, cells were harvested by centrifugation (5,000 g, 30 min, 4 °C) and the pellet was resuspended in washing buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl) then stored at -80 °C overnight22. Frozen E. coli were thawed and incubated on ice for one hour after the addition of lysozyme, DNAse I and PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) to final concentrations of 0.25 mg/mL, 10 µg/mL and 0.1 mM, respectively22. Partially lysed cells were then disrupted by three consecutive cycles of sonication (30 s, amplitude 45) performed on a Q700 sonicator system (QSonica). Cellular debris were discarded following centrifugation (10,000 g, 20 min, 4 °C)22. The ThnS protein was purified with an ÄKTA avant system (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA) using Strep-tag affinity chromatography (wash buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, and Elution buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM desthiobiotin) on a 5 mL StrepTrap HP column (GE Healthcare). Fractions containing the protein of interest were pooled. Protein purity was assessed using 12.5% SDS-PAGE analysis (Coomassie staining)22. Protein expression was confirmed by performing MALDI-TOF MS analysis on gel bands previously obtained by SDS-PAGE. Protein concentrations were measured using a Nanodrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Madison, WI, USA)22.

Monitoring imipenem, penicillin G, cefotaxime and ascorbic acid degradation using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC–MS)

A stock solution of 10 mg/ml of Imipenem and Cilastatin was freshly prepared in water from the perfusion mixture of both compounds (500 mg/500 mg; Panpharma, Luitre, France). Stock solutions of Penicillin G, Cefotaxime and ascorbic acid were prepared at 1 mg/mL in water from pure standards (Sigma Aldrich, Lyon, France). 100 μL of ThnS enzyme aliquots at 1 mg/mL were spiked with Imipenem/Cilastatin or Penicillin G or Cefotaxime or ascorbic acid at final concentrations of 10 μg/ml, then incubated at room temperature. Negative controls consisted of PBS 1 × spiked with the antibiotics or ascorbic acid alone. Triplicate samples were prepared and for each replicate, 30 μL of solution was collected at 0, 4 and 24 h. 70 μL of acetonitrile was then added to each sample, and tubes were vortexed for 10 min at 16,000 g in order to precipitate proteins. The clear supernatant was collected for analysis using an Acquity I-Class UPLC chromatography system connected to a Vion IMS Qtof ion mobility-quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometer as described previously22,23. To summarise, samples were injected into a reverse phase column (Acquity BEH C18 1.7 μm 2.1 × 50 mm, Waters), and compounds were ionised in the positive mode using a Zspray electrospray ion source. Ions were monitored using a high-definition MS (E) data independent acquisition method. 4D peaks, corresponding to chromatographic retention time, ion mobility drift time and parents/fragments masses, were then collected from raw data using UNIFI software (version 1.9.3, Waters). The lactam rings of Imipenem and Penicillin G can be hydrolysed respectively to Imipenemoic acid and benzyl penilloic acid; these structures were targeted by m/z ratio, retention time and drift time. The hydrolysed forms of Cefotaxime and ascorbic acid were not monitored.

Structural prediction and alignment of ThnS

The protein sequence of ThnS was submitted to the Phyre2 web portal (http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index) for protein modelling, prediction and analysis. The resulting pdb model was visualised and structurally aligned with the published structure of UlaG from Escherichia coli (PDB : 2WYM)24 using the PyMOL 1.8.6.0 software (https://github.com/schrodinger/pymol-open-source).

Nuclease and ribonuclease activity testing

Enzymatic reactions were performed by incubating each polynucleotide or polyribonucleotide (1 µg) with 10 µg of purified ThnS enzyme alone or in the presence of a metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor (10 mM of EthyleneDiamineTetraacetic Acid, EDTA) and using a final volume of 15 µl at 37 °C for two hours. Single-stranded DNAs were synthetic polynucleotides (Suppl. Table S2); double-stranded DNA (130-bp) was obtained by annealing positive and negative single-stranded DNAs (130-bp) in a thermocycler at temperatures decreasing from 95 °C to 25 °C over the course of two hours. The enzymatic reactions were conducted in CutSmart Buffer (New England Biolabs, 50 mM Potassium Acetate, 20 mM Tris–acetate, 10 mM Magnesium Acetate, 100 µg/ml BSA pH 7.9) and using a final volume of 15 µl at 37 °C for two hours. After incubation, the material was loaded onto denaturing PolyAcrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (dPAGE) at 12%. A negative enzyme control, Bacillus subtilis Glycine Oxidase (GO), was expressed and purified under the same conditions as ThnS and tested. A Turbo DNAse enzyme was also used as positive control enzyme at concentration of 1 U. To evaluate ribonuclease activity, the Escherichia coli RNA was purified using the RNeasy columns (Invitrogen, USA). The integrity of the RNA preparations was tested on a Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent), using Agilent RNA 6000 Pico LabChip and shown a high integrity with RNA Integrity Number (RIN) = 10. The enzymatic reactions were performed by incubating RNA (1 µg) with 10 µg of purified ThnS enzyme alone and in the presence of a metallo-β-lactamase inhibitor, in CutSmart Buffer and using a final volume of 15 µl at 37 °C for two hours. After incubation, RNA-hydrolysing activity was visualised on the RNA 6000 Pico LabChip (Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer). The B. subtilis Glycine oxidase was also used as negative control enzyme.

References

Wang, H., Fewer, D. P., Holm, L., Rouhiainen, L. & Sivonen, K. Atlas of nonribosomal peptide and polyketide biosynthetic pathways reveals common occurrence of nonmodular enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 9259–9264 (2014).

Finking, R. & Marahiel, M. A. Biosynthesis of nonribosomal peptides. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58, 453–488 (2004).

Weissman, K. J. & Leadlay, P. F. Combinatorial biosynthesis of reduced polyketides. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 925–936 (2005).

Fechtner, J. L. Fungi and bacteria antibiotics: a review. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 31, 1217–1225 (1944).

Ogawara, H. Comparison of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in antibiotic-producing and pathogenic bacteria. Molecules 24, 1–55 (2019).

Parker, W. L. et al. SQ 27,860, A simple carbapenem produced by species of Serratia and Erwinia. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 35, 653–660 (1982).

Derzelle, S., Duchaud, E., Kunst, F., Danchin, A. & Bertin, P. Identification, characterization, and regulation of a cluster of genes involved in carbapenem biosynthesis in Photorhabdus luminescens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68, 3780–3789 (2002).

Hayes, F. & Van Melderen, L. Toxins-antitoxins: diversity, evolution and function. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 46, 386–408 (2011).

Baker, F. et al. Thienamycin, imipenem and new members of the carbapenem class of β-lactam antibiotics. In: IUPHAR 9th International Congress of Pharmacology London 1984 105–109 (1984). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-17613-7_11.

Barbe, V. et al. Complete genome sequence of Streptomyces cattleya NRRL 8057, a producer of antibiotics and fluorometabolites. J. Bacteriol. 193, 5055–5056 (2011).

Rodríguez, M., Núñez, L. E., Braña, A. F. & Carmen Méndez, J. A. S. Identification of transcriptional activators for thienamycin and cephamycin C biosynthetic genes within the thienamycin gene cluster from Streptomyces cattleya. Mol. Microbiol. 69, 633–645 (2008).

Coulthurst, S. J., Barnard, A. M. L. & Salmond, G. P. C. Regulation and biosynthesis of carbapenem antibiotics in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 295–306 (2005).

Fernandez, F. J. et al. The UlaG protein family defines novel structural and functional motifs grafted on an ancient RNase fold. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 273 (2011).

Keshri, V. et al. Promiscuous enzyme activity as a driver of allo and iso convergent evolution, lessons from the β-lactamases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6260 (2020).

Kato, Y., Takahashi, M., Seki, M., Nashimoto, M. & Shimizu-Ibuka, A. RNA-hydrolyzing activity of metallo-β lactamase IMP-1. PLoS ONE 15, e0241557 (2020).

Okuhara, H. A. Natural beta-lactam antibiotics. Ann. Rev. Microbiol. 34, 159–181 (1980).

Karakonstantis, S., Kritsotakis, E. I. & Gikas, A. Treatment options for Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Acinetobacter baumannii co-resistant to carbapenems, aminoglycosides, polymyxins and tigecycline: an approach based on the mechanisms of resistance to carbapenems. Infection https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01520-6 (2020).

Gupta, S. K. et al. ARG-ANNOT, a new bioinformatic tool to discover antibiotic resistance genes in bacterial genomes. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 58, 212–220 (2014).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-gutiérrez, S., Silla-martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl : a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2-approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Diene, S. M. et al. Human metallo-β-lactamase enzymes degrade penicillin. Sci. Rep. 9, 12173 (2019).

Diene, S. M. et al. Dual rnase and β-lactamase activity of a single enzyme encoded in archaea. Life 10, 1–12 (2020).

Garces, F. et al. Molecular architecture of the Mn2+-dependent lactonase UlaG reveals an RNase-like metallo-β-lactamase fold and a novel quaternary structure. J. Mol. Biol. 398, 715–729 (2010).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the IHU Méditerranée Infection, Marseille France and CookieTrad for English proof reading of the manuscript are gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

This work was supported by the French Government under the “Investments for the Future” programme managed by the French National Research Agency (ANR), Méditerranée-Infection (10-IAHU-03) and was also supported by the Région Provence Alpes Côte d’Azur and European ERDF PRIMMI funding (European Regional Development Fund—Plateformes de Recherche et d'Innovation Mutualisées Méditerranée Infection).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.R.: conceived and designed the study. S.M.D., L.P., N.A, S.A.B., S.A., L.H. P.P.: performed analyses and interpreted data. S.M.D., L.P., N.A, S.A.B, S.A., P.P. and D.R.: drafted the manuscript. S.M.D, J.-M.R., E.C., P.P., and D.R.: made corrections and critical revisions. All of the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Diene, S.M., Pinault, L., Baron, S.A. et al. A metallo-β-lactamase enzyme for internal detoxification of the antibiotic thienamycin. Sci Rep 11, 10062 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89600-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-89600-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.