Abstract

Soil erosion (SE) and climate change are closely related to environmental challenges that influence human wellbeing. However, the potential impacts of both processes in semi-arid areas are difficult to be predicted because of atmospheric variations and non-sustainable land use management. Thus, models can be employed to estimate the potential effects of different climatic scenarios on environmental and human interactions. In this research, we present a novel study where changes in soil erosion by water in the central part of Iran under current and future climate scenarios are analyzed using the Climate Model Intercomparison Project-5 (CMIP5) under three Representative Concentration Pathway-RCP 2.6, 4.5 and 8.5 scenarios. Results showed that the estimated annual rate of SE in the study area in 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019 averaged approximately 12.8 t ha−1 y−1. The rangeland areas registered the highest soil erosion values, especially in RCP2.6 and RCP8.5 for 2070 with overall values of 4.25 t ha−1 y−1 and 4.1 t ha−1 y−1, respectively. They were followed by agriculture fields with 1.31 t ha−1 y−1 and 1.33 t ha−1 y−1. The lowest results were located in the residential areas with 0.61 t ha−1 y−1 and 0.63 t ha−1 y−1 in RCP2.6 and RCP8.5 for 2070, respectively. In contrast, RCP4.5 showed that the total soil erosion could experience a decrease in rangelands by − 0.24 t ha−1 y−1 (2050), and − 0.18 t ha−1 y−1 (2070) or a slight increase in the other land uses. We conclude that this study provides new insights for policymakers and stakeholders to develop appropriate strategies to achieve sustainable land resources planning in semi-arid areas that could be affected by future and unforeseen climate change scenarios.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Changes in land uses have consistently been described because of rapid population growth and the expansion of human settlement around the world1,2,3,4,5,6,7. These changes play important roles in shaping the landscape and altering land resources, sometimes with negative impacts8. Numerous scholars have concluded that unregulated land-use changes lead to environmental degradation that poses a major threat to the socioeconomic and ecological sustainability of soil as a vital resource9,10,11. Increasing pressure on land resources because of unsustainable cultivation, overgrazing, deforestation, climate change and drought, urbanization and poor land management practices are worsening land degradation on a global scale12,13,14,15. Among them, soil erosion (SE) is one of the common forms of land degradation that is related to unsustainable environmental management. Soil erosion is particularly severe in arid and semi-arid regions15,16,17,18,19,20.

SE is a complex process resulting from the impacts of wind, precipitation, human activities and associated runoff processes that are influenced by parent material, soil properties, relief and vegetation cover21,22. Although SE may occur naturally, anthropogenic activities such as land-use change, agriculture, livestock grazing or deforestation are known to exacerbate erosion and soil degradation23,24,25. Therefore, SE is considered a natural and human-induced challenge9,13,22, that leads to severe adverse socioeconomic and environmental damage in many societies26,27. Despite the important implications of SE on sustainable use of soil; however, there is limited information on current and future scenarios. The dearth of this information is linked to the complexity of erosion processes which makes SE estimation expensive, time-consuming and difficult28,29. This difficulty has resulted in the development of various models and tools that seek to simplify SE modelling and improve our understanding of the pattern and processes of SE.

The Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE)30,31 model is widely used for estimating SE because it integrates many of the components of the SE process13,26,29,32,33. Apart from the anthropogenic factors driving SE, recent studies show that other factors influencing land degradation are climate-related32,34,35. On the other hand, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has launched the four future scenarios for earth greenhouse gases (GHGs) emission, which is known as Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) 2.6, 4.5, 6, and 8.536. These scenarios simulate different GHGs emission, the RCP2.6 refer to low GHGs emission, the RCP4.5, and RCP6 express as stabilization scenarios, while RCP8.5 denote high GHGs emission37. Studies have been carried out to predict the impact of future climate on soil erosion by using different CMIP5-RCP scenarios (i.e. Tibetan Plateau38; Lancang–Mekong River39; Minab Dam Watershed35; Burkina Faso40; mid-Yarlung Tsangpo River region41).

SE is a natural geomorphological process (erosion, transport and sedimentation) but after human disturbances can be considered as a land degradation one, which has been a recurring challenge for decades over the world for stakeholders, and especially, in countries such as Iran. Recently, scientists have examined land degradation indicators including desertification42, deforestation43, salinization44, alkalization of soils45, overgrazing46, intensive land-use changes47, and especially, water and wind erosion48,49. Many of these studies integrated remote sensing, Geographic Information System (GIS) and the RUSLE approach for the estimation of SE50,51,52,53,54,55. Other recent techniques such as Artificial Neural Networks or Machine Learning techniques are also becoming popular for erosion simulation and modelling in Iran29,56,57. However, despite the numerous studies on SE estimation, there is limited information on SE estimation based on future climate change (CC) scenarios in Iran and other arid and semi-arid countries. Thus, the main goals of this research are to 1) estimate the current SE in the central part of Iran, and 2) predict SE changes under future climate scenarios using Climate Model Intercomparison Project-5 (CMIP5). We hypothesize that this will provide important information for policymakers and stakeholders to develop appropriate strategies to achieve sustainable land resource planning, utilization and management.

Material and methods

Study area

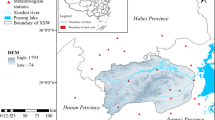

This study was conducted in an area covering 5833 km2 in Alborz Province located in central Iran. The area lies between the latitude 35° 31′–36° 21′ N and longitude 50° 10′–51° 30′ E (Fig. 1). The climate of this area is classified as semi-arid bordering to arid58. Mean annual rainfall reaches 251 mm and the mean monthly temperature 14.1 °C. During the year, the temperature typically varies from − 2 to 35.2 °C and the precipitation ranges from 1 or 2 mm to 78 mm in the rainy month (https://weatherspark.com). The study area is characterized by a range of land use and land cover categories including rangeland, agricultural land, saline and bare lands.

Study area with soil sampling sites shown on the Digital Elevation Model (DEM), values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Data collection and pre-processing

The soil database was elaborated for several years by the Soil Science Department of the University of Tehran. To predict the spatial distribution of soil texture and soil organic carbon of the study area; Decision Tree (DT) and Artificial Neural Network (ANN) models were generated using 70% of data obtained from laboratory analysis of soil samples. Model testing was based on 15% of the data while 15% was used for model validation. As the performance of the DT is better than ANN (Appendix 1 and 2), the output of the DT model was adopted as the main input for calculating the K factor59.

Digital elevation models (DEM) and cloud-free Landsat images of the study area were obtained from the United State Geological Survey (USGS) website at (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov). The images obtained include Landsat 7 Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM +) Level-1 of 27 October 2005, 10 November 2010, 24 November 2015 and 18 October 2019. SCL-off error in the images was corrected using Landsat Toolbox extension in ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview) (ESRI, USA).

Downscaled CMIP5 monthly precipitation parameter was acquired from the WorldClim Data Portal at 1 km resolution (https://www.worldclim.org/). The CMIP5 data from Global Climate Models (GCMs) are available for four representative concentration pathways (RCPs) as released by the twenty-first century in its 5th Assessment Report (IPCC, 2014). The GCM outputs have been downscaled and calibrated, (i.e. bias-corrected using WorldClim v.1.4 as current baseline climate)60,61. Previous research has shown that different CC scenarios produced different result in assessments of GCMs performance in Iranian territory62,63. In this research, the HadGEM2-ES model was used for the calculation of rainfall erosivity R-factor. For an investigation of the impacts of future CC on SE by water, the output layers of the current climate and projected CC according to the HadGEM2-ES model and several RCP (RCP2.6, 4.5, and 8.5) were used in our calculation of the R factor.

Soil erosion estimation

In this study, RUSLE31,64 was used for estimating and predict SE. This is one of the universal pioneer methods for SE estimation and modelling65. It is recognized as an empirical model limited to calculating rill and inter-rill erosion, without considering gully erosion21. SE estimation using RUSLE is based on the following Eq. (1):

where \(\vartheta\) represents the annual soil loss (metric tons per hectare per year); R is the rainfall erosivity (megajoule millimeters per hectare per hour per year); K means soil erodibility (metric ton hours per megajoules per millimeter); LS corresponds to the topographic factor (length and steepness- unitless); C is the land cover/ land use factor (unitless); and, P characterizes support/conservation practice (unitless).

Rainfall erosivity R

R factor refers to the kinetic energy of raindrops which could significantly affect the stability of soil aggregates and enhance soil loss66,67,68,69,70. In this study, the R factor was calculated using a monthly database approach as following31,71,72,73,74 in Eq. (2):

where R is a rainfall erosivity factor (MJ mm ha−1 h−1 per year); \(p_{i}\) represents monthly rainfall (mm); and, \(P\) corresponds to the annual rainfall (mm).

The R factor was calculated for two different periods to account for the past, current and future values. The initial value of the R factor was obtained by computing the average values from 1990–2019 (Raverage (1990–2019)) and was considered as a representative average result for the past and current time interval. For future climate projection, two different average values were selected for the R factor. The first one was from 2040–2060 (Raverage (2040–2060)) and the second one from 2060–2080 (Raverage (2060–2080)).

Soil erodibility K

K factor reflects the susceptibility of soil aggregates to detachment by raindrops and its transportation by runoff75,76,77. The K values were calculated using soil data derived from the DT model simulation78 based on Eq. (3):

where SAN: sand%, SIL: silt%, CLA: clay%, OM: organic matter%, SN1 = 1 − SAN/100.

Afterwards, each pixel was assigned a K value in the GIS environment.

Topographic factor LS

The Slope length (L) and steepness (S) play vital roles in SE and reflect the potential contribution of topography in runoff and SE65. The LS factor was computed using the following equation79,80 (Eq. 4):

where FlAc is the flow accumulation (contributing to the upslope area to a given cell) with a cell size of 30 m. Flow accumulation map was derived from DEM in the ArcHydro extension of the spatial analyst tool.

Cover management factor (C)

The C factor plays a vital role against SE by protecting the soil surface from the direct effect of raindrops, where erosion is significantly correlated with vegetation coverage72,81,82. In this study, the C value was generated by applying Eq. 5, which is based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) as follows83:

where \(\forall\) = 2 and \(\gamma\) = 1. Although there are other three approaches for determining the C factor, the remote sensing approach based on NDVI has been widely used13,84,85. The average C factor (Cx) of C2005; C2010; C2015 and C2019 was calculated and used as a constant input for addressing the impact of climate projection on SE. It is worth to mention here that satellite images were collected in November and April for each target year, then the average NDVI was calculated for both images to get a representative image for each target year. This approach was undertaken to overcome the fact that NDVI varies widely throughout the year because it is affected by vegetation growth dynamics.

Support practice factor P

The P factor refers to soil loss from up and downslope tillage under specific supporting practices. For instance, contouring agriculture, strip-cropping and terracing affect the direction of surface runoff and modify flow pattern86,87. In this study, the P-factor map was derived from DEM and the appropriate value was assigned to each category of the slope following Morgan88 (Table 1).

The spatial pattern of SE was derived by multiplying all the factor together (pixel-by-pixel) to generate a current and future SE map of the study area. In terms of future SE, LS, K, P factors were considered as constant (similar to the current situation), C factor was calculated as an average of (C2005, C2010, C2015, C2019), while R factor was estimated as an average for two different periods the 2050s and 2070s. Hence, the future erosion model could be express ass follow:

The methodology was represented in a flowchart in Fig. 2, and Table 2 shows a summary of the data sources used in this study.

Statistical analysis

We estimated mean values, standard deviations and mean errors for SE factors and total erosion rates using the Extract Values by Points’ tool of ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview ). Finally, the correlation between total SE and each respective factor was determined using a correlation matrix.

Results

Factors influencing soil erosion

In this study, the soil erodibility (K) factor widely varied. It ranges from 0.2 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1 to 0.4 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1 with a mean value of 0.25 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1. This variation appears to be influenced by land use and soil type. For instance, the K factor values range from 0.11 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1 (less resistant to SE) in the northern, eastern and southern parts of the study area, to 0.45 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1 (most resistant to SE) the central, northwest and western parts. Erodibility is particularly high in the cultivated area (0.3–0.44 t ha h ha−1 MJ−1 mm−1) but lower in areas with high relief (0.25–0.01 t ha h ha−1 MJ−1 mm−1) (Fig. 3a).

Spatial pattern of (a) K factor, (b) LS factor, (c) P factor, (d) R factors in Central Iran, values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Figure 3b shows that the mean value of the slope length (LS) factor is 4. In the study area, the LS factor ranges from 0.5 to 8.6. The LS value is higher in the high and dissected escarpments in northern, northwest, and northeastern parts of the study area than in the south and southwest ones that are characterized by gentle slopes and low runoff potential. Although the average P factor value is 2.5, more than 60% of the study area registered a low P factor (Fig. 3c). The high values of the P factor coincide with the physiography and severity of slopes in the study area.

Rainfall erosivity factor ranged between 84 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 per year in lower-lying terrain areas but increased rapidly to 164 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 per year at higher terrain (Fig. 3d). The annual mean of R-value in the study area was 112 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 per year.

Figure 4 shows the normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI) and the land cover management factor in the study area. Variation in NDVI values (Fig. 4a) during the period of this study were low in marked contrasts to the values of cover management distribution factor. Figure 4b shows C factor values in 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019. There was a remarkable difference in the C factor during the period of this study. This is particularly significant in 2005 and 2019 and 2010 and 2015. Consequently, the land covers during 2010 and 2015 are the most vulnerable to increasing trend of erosion.

(a) NDVI; and (b) Cover management (C-factor) distribution (2005; 2010; 2015; 2019), values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

The spatial pattern of soil erosion

Figure 5 shows that the estimated annual rate of SE in the study area during 2005, 2010, 2015 and 2019 reaches approximately 12.8 t ha−1 y−1. The northern region of the study is more prone to soil erosion as this part of the study area accounts for more than 20 t ha−1 y−1 of erosion in contrast to the southern parts > (1 t ha−1 y−1).

Spatial pattern of soil erosion in the study area, values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Table 3 indicates the area affected per SE categories (%) under both the current and projected climate change scenarios. The annual soil loss in most parts of the region range between 0.1 and 5 t ha−1 y−1.

Table 4 shows the matrix of statistical correlation between RUSLE criteria and the values of SE in the study area. The table indicates that although slope length and management practices are correlated with SE in the study area, slope length has a greater influence on SE than management practices. This is in marked contrast with R, K and C factors that seem to be more fragile in relation to semi-dry physiographic features in the study area.

Projected soil erosion

Three scenarios of projected R factor for 2040–2060 and 2060–2080 were determined from the fifth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5) models. A comparison of the baseline projected R factor values calculated from monthly rainfall rates of 40 years (i.e. 1960–2000) with the future values of projected R factor derived from three Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) is shown in Fig. 6. The highest values of the R factor (< 150 MJ mm ha−1 h−1) are mainly concentrated in the west (a) and northwestern (b and c) part of the study area. A similar pattern is observed in the projected values (Fig. 6d–f). Figure 7 shows the changes between baseline and projected SE in the study area under three CC scenarios of RCPs. This confirms that the regions with higher values of the R factor are located in the eastern and northeastern regions.

Projected changes in R factor values based on the HadGEM2-ES model and RCP for different time series, values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Projected future changes of R factor compared with the baseline (1970- 2000), values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Projected future SE values indicate that there will be a high soil loss (> 5 t ha−1 y−1) in the north, northwest, and far southern parts of the study area in three scenarios of RCPs (Fig. 8). These future changes show that the spatial distribution of SE is similar to the baseline values (Fig. 5). This future simulation indicates that those same areas would be subject to accelerate SE if adequate soil conservation strategies are not developed and implemented. Notably, areas of high erosion values (> 5 t ha−1 y−1) reach up to 19.7% in the RCP2.6 (2060–2080) and 19.1% in the RCP8.5 (2060–2080) (Table 3 and Figs. 8 and 9). Spatial differences between RUSLE under different RCPs scenarios and RUSLE-2019 show an accelerated erosion trend in most areas of the study area. The highest values of SE were mainly located in the northwestern parts for the three RCPs (re-coloured), and especially under the RCP8.5 scenario.

Projected future SE changes under three climate scenarios of RCPs (SE: Soil Erosion), values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Spatial differences between RUSLE under different RCPs scenarios and RUSLE-2019, values of pixels were mapped by ArcGIS 10.5 (https://www.esri.com/en-us/about/about-esri/overview).

Detecting the land uses prone to SE

Table 5 shows the results of baseline and future SE quantities according to the land cover types in the study area. There is an upward trend in the quantities of SE. Rangeland areas accounted for the highest amount of SE especially in RCP2.6 (2070) and RCP8.5 (2070) with an overall amount of 4.25 t ha−1 y−1 and 4.1 t ha−1 y−1, respectively. Then, they are followed by agricultural areas with 1.31 t ha−1 y−1 (RCP2.6 in 2070) and 1.33 t ha−1 y−1 (RCP8.5 in 2070). Also, bare land areas were predicted to register up to 0.34 t ha−1 y−1 and 0.35 t ha−1 y−1 in RCP2.6 (2070) and RCP8.5 (2070), respectively. The lowest amount of SE was estimated in the residential areas reaching 0.61 t ha−1 y−1 and 0.63 t ha−1 y−1 in RCP2.6 (2070) and RCP8.5 (2070), respectively.

Table 6 summarizes the changes in statistical parameters from the baseline for each land cover. SE was projected to increase in the 2070s under both RCP2.6 and RCP8.5. In contrast, predicted SE in RCP 4.5 is expected to decline in rangelands by − 0.24 t ha−1 y−1 (the 2050s), and − 0.18 t ha−1 y−1 (the 2070s) but it would slightly increase for the other land-use types.

Discussion

In the semi-arid regions of Iran, SE by water is one of the most complex environmental problems threatening agricultural fields and, subsequently, human well-being. SE in these areas has been evaluated by several studies dealing with water erosion. However, there is a limited number of investigations that have rarely approached the topic of SE rates prediction according to climate covariates across remote areas89. In the current study, the impact of future CC on SE was investigated in the semi-arid central part of Iran featured by fragile and motivating properties for land and biodiversity degradation. We did not consider wind erosion in this study, but it is relevant to highlight that future approaches, should combine both water and wind types90. The five RUSLE factors (R, K, C, LS, and P) were extracted utilizing information from field survey and remote sensing sources. Then, these thematic raster layers were modelled and merged in the GIS environment to calculate the annual rates of SE and considers the spatial–temporal dimensions of SE in the Central Part of Iran. In this regard, given the integration of improved methods in effectively calculating erosion with recent data sources, the provided SE values by water could indicate an elevated accuracy and objectivity considering others obtained from prior studies (Table 7).

The baseline and downscaled R factor in this study was computed and mapped based on monthly precipitation data obtained by WorldClim v.1.4 and v2.1data Portal at 1 km. resolution. Accurate mapping of baseline R factor values led to improved results in estimating SE, especially in an area with low annual precipitation rates and highly governed by climatic conditions. These results could give new insights, for example, to foresee especially the occurrence of rills and gullies among other SE processes because they are very sensitive to changes in rainfall patterns and human impacts99,100.

Based on the validated modelling process (DT and ANN) fed by the analysis results of 362 soil samples, the spatial distribution of the K factor was mapped. Moreover, K factor values are improved because of testing two reliable models in calculating soil properties based on data derived from remote sensing and extended field survey. In this context of statistical calibration, the DT model provided strong correlations in calculating the soil characteristic with regression of R2 above 70% in all measurements. However, there is still a further way to improve this model if we consider recent investigations. For example, in China, Wang et al.101 confirmed that based on the nonlinear best fitting techniques, K factor prediction by combining Geometric Mean Diameter based and soil organic matter (SOM). Another recent study conducted in Uruguay by Beretta-Blanco and Carrasco-Lettelier102 demonstrated that the implementation of soil taxonomy, chemical composition, and parent materials could increase the accuracy in linear estimations of this factor. These ideas agree with recent reviews published about soil mapping techniques which remark the importance of not obviating key properties since the soils are results of multiple and complex interactions103,104,105. In our study, the average K value was 0.25 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1, whereas the average OM was 1.9% and clay 27.43%, which contribute markedly to rising the K value in the study area. However, the K value in the study area in line with other studies in the Middle East and other semiarid regions. For instance, in southern Syria K value was ranged from 0.22 to 0.36 t ha h ha−1 MJ−1 mm−168, in western Iran, was between 0.20 and 0.59 0.22 to 0.36 t ha h ha−1 MJ−1 mm−1106, while the average K value was 0.13 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1 in northern Turkey107.

The intense spatial–temporal variation of NDVI values has greatly affected the annual C factor values108. In this sense, C factor values in 2005, 2019 remarkably different from those in 2010, 2015, which could mainly attribute to megadrought events that hit the central part of Iran in that years109. However, C Factor, as the R factor, is largely sensitive to the areas characterized by a semi-arid environment and human impacts110. Consequently, these two factors led to the complicated and accelerated dimensions of SE as the current study showed. Observing our results, also non-agricultural must be considered when this factor changes such as residential areas or bare lands. Karpilo et al.111 stated that there is little consensus in the erosion-science community about the correct values of the C factor for the effects of various slope-protection materials. Therefore, we recommend that policymakers and stakeholders pay attention to that areas especially where both factors show drastically changes from nowadays to the simulated scenario to avoid irreparable loss of fertility (bare soils) or floods and extreme sediment discharges (urban areas).

LS and P factors were mapped based on the reclassification of the slope raster layer. These two were found to be the most influencing factors for erosion acceleration. These results agree with Panagos et al.112 who highlighted that this factor is quite obviated. They estimated that the P factor could reduce the risk of SE by 3%, with vegetation cover and stone walls obtaining the largest positive impact. However, these results can vary at different scales. Paying attention to research conducted at the hillslope scale, Rodrigo-Comino et al.113 estimated in a Mediterranean old clementine plantation for the LS factor using two pre-established algorithms and ISUM (Improved Stock Unearthing Method) that the micro-topographical changes can show frequent irregularities in SE results. The authors observed high differences among the areas predicted at the moment of furrow construction and the moment of data survey with soil mobilization rates of about 56.9 m3 (8.3 mm yr−1) in 19 years for 360 m2. Comparing LS and P factor maps with the final map of the RUSLE model explained that with rising length and percentage of the slope of the area, intensity and rate of soil erosion also is increased which is along with the result of Mohammadi and et al.54.

Multi-digital SE mapping enables calculation of the annual rate of SE which was reached to more than 20 t ha−1 y−1. The spatiotemporal variation of the resulting SE indicates that there is a spatial concentration of erosion in the northern, northeast, and northwestern regions. The given results indicate that the northern, northeastern and northwestern regions were the most affected in 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2019, respectively. These areas are characterized by mountainous terrain and steep slopes. Our results visibly confirmed that soil erosion could be easily affected by a different kind of land cover. The land use map (Appendix 3) showed that rangelands are dominated in the northern, northeastern and northwestern regions which has the highest soil erosion values, where LS factor ranges from 4–85 (Fig. 3b). On the contrary, bare land dominates in the gentle slope area (LS factor = 0.5–1), which minimize erosion processes. In this regard, Table 4 showed that the highest correlation (r = 0.77, p < 0.05) between topography (LS) and soil erosion, which confirm the eminent role of topography in developing the soil erosion process in the study area. In light of this rangeland and following agricultural regions showing the highest value of SE explosibility, demanded higher protection and management. Thus, that area should be considered in any future land conservation plan as a high priority considering topographical changes as key drivers of weather changes and SE intensity114,115,116. This finding completely confirmed the result of the research for Borrelli et al.117, in which they discussed in the high slope areas with rare vegetation the risk of SE is high. However, bare land has shown the least values of SE in the current situation, which located on a gentle slope (central part) in compression with other land use.

To assess the effect of future CC on SE susceptibility, data derived from CMIP5 by three scenarios of CMIP5-RCP were used in calculating future values of the projected R factor. However, the utilized approaches in the present study are consistent with those presented by Yigini and Panagos118 which assumed that future changes in precipitation values will inevitably lead to a change in SE rates globally. Future values of SE were predicted in the study area according to the regional CC concerning three scenarios of RCPs. These future values indicate that the northern, northwest and northeastern regions are the most sensitive and vulnerable to CC, especially under RCP8.5 which consistent with the pathway that involves huge amounts of greenhouse gas emissions119. High SE rates are located mainly along mountainous terrain; hence, it will be the most affected by changes in precipitation patterns for climatic characteristics in semi-arid areas120. Changes include an increase in extreme precipitation events across the study area, thus a greater precipitation intensity with increase SE potentials by runoff in the steep slope regions. Within this context, prediction of future SE is highly important to provide policymakers with appropriate tools for developing action plans against different possible soil erosion scenarios. Alewell et al.121, stressed the importance of modeling SE on a different scale for soil conservation planning and policy governance. Meanwhile, Borrelli et al.117 emphasized the importance of adaptation of conservation strategies based on RCP2.6 and RCP8.5 scenarios.

Future projections of CC in this study provide a spatial interpretation of the future SE in light of different scenarios. Despite the accuracy and quality of available results and the possibility of using them in the management of soil erosion, some inputs lead to uncertainty in present simulation outcomes. For example, the R factor values were calculated based on the monthly and yearly averages of precipitation (Eq. 3), based on 3 scenarios of RCPs, are still not certain, which could explain the low correlation between projected future R factor and SE in Table 4. However, the adopted calculation method is a suitable alternative in light of the scarcity of data required to calculate the values of the R factor according to the kinetic raindrop energy approach (basically, rainfall records at 15–30 min time interval). Besides this, there is a great difficulty in predicting future C factor with complete accuracy, because the C factor is complex and highly sensitive to environmental changes as was above-discussed. The current spatial outputs are of sufficient reliability for the K, LS and P factors. Consequently, this study presented serious and reliable spatial scenarios about the future of SE in the study area.

Considering all the factors, it is obvious that SE in the northern and northeastern parts which are dominated by rangeland, higher precipitation, and mountains (high relief topography) is suffering from severe erosion and also have the highest potential for SE. After the assessment of the research results and justifying them according to the geological factors in the study area, we concluded that geology also plays an important role in soil erosion activation at large scales but is mainly reflected in the form of the susceptibility of soil erosion (K-factor). Igneous formations that cover the north part of the study area are correlated with the minimum susceptibility of K-factor while basaltic and tuff formations, due to the lightweight and high porosity, can contribute more to soil formation processes and therefore to the soil erosion factor. In the foothill which sedimentation is the main characteristic, soil erosion has experienced a low rate too. Two parts of the study area revealed a high susceptibility, one is in the Taleghan area that the signs of massive erosion are obvious, and another one located at the Eshtehard with the evidence of gully erosion and dissolution erosion types.

Remarkably, this investigation verified the findings of other researchers in this part of Iran as well as many other regions of Iran94,122. The output of this research can be used to take measures of sustainable agriculture in an arid study area environment and to work on identifying priorities for spatial conservation. Also, SE could be mitigated by maintaining vegetation cover, using cover crops, reducing soil disturbance by tillage among other measures123,124,125,126.

Conclusions

Soil erosion is one of the most pressing environmental issues in light of the accelerating impacts of global climate change. Multisource GIS provides an objective and advanced platform in soil erosion modeling with accurate and reliable results. Spatial correlation between climate change, soil erosion and land cover change using global models, such as RUSLE, can effectively assist in the spatial management process, especially in arid environments. In the present study, the spatial–temporal distribution of potential soil erosion in the central part of Iran was determined based on future climate change scenarios. The experimental RUSLE model was chosen based on the data specificity of the study area. This model provides the possibility to investigate the current and future spatial distributions of soil erosion rate relying on predictive data. The key findings are summarized, as follows:

-

1.

The average R factor was 112 MJ mm ha−1 h−1 per year, P factor was 2.5, and the K value was 0.25 t·ha·h·ha−1·MJ−1·mm−1. The C factor was ranged between 0 and 1, while LS was 0.5–8.6.

-

2.

The estimated annual rate of SE is approximately 12.8 t ha−1 y−1 in Central Iran.

-

3.

Projected future SE values indicate that there will be a high soil loss (> 5 t ha−1 y−1) in the north, northwest, and far southern parts of the study area in three scenarios of RCPs

-

4.

Rangeland areas registered the highest amount of SE especially in RCP2.6 (2070) and RCP8.5 (2070), followed by agricultural areas. Also, bare land areas were predicted to considerable SE rates

-

5.

The lowest amounts of SE were estimated for the residential areas in RCP2.6 (2070) and RCP8.5 (2070).

-

6.

SE will be increased in the 2070s under both RCP2.6 and RCP8.5. On the contrary, RCP 4.5 showed that the total SE was predicted to be decreased in rangelands and increased slightly under other land use.

The output of this research will help decision-makers and local authorities for developing a local plan for land conservation against SE by different climate change scenarios.

References

Ayoubi, S., Mokhtari Karchegani, P., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Honarjoo, N. Soil aggregation and organic carbon as affected by topography and land use change in western Iran. Soil Tillage Res. 121, 18–26 (2002).

Kelishadi, H., Mosaddeghi, M. R., Hajabbasi, M. A. & Ayoubi, S. Near-saturated soil hydraulic properties as influenced by land use management systems in Koohrang region of central Zagros, Iran. Geoderma 213, 426–434 (2014).

Havaee, S., Ayoubi, S., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Keller, T. Impacts of land use on soil organic matter and degree of compactness in calcareous soils of central Iran. Soil Use Manag. 30(1), 2–9 (2014).

Mohammed, S. et al. Impacts of rainstorms on soil erosion and organic matter for different cover crop systems in the western coast agricultural region of Syria. Soil Use Manag. https://doi.org/10.1111/sum.12683 (2020).

de Jesús Guevara Macías, M., Carbajal, N. & Vargas, J. T. Soil deterioration in the southern Chihuahuan Desert caused by agricultural practices and meteorological events. J. Arid Environ. 176, 104097 (2020).

Enaruvbe, G. O. & Atafo, O. P. Land cover transition and fragmentation of River Ogba catchment in Benin City, Nigeria. Sustain. Urban Areas 45, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.11.022 (2019).

Saleh, B. & Rawashdeh, S. A. Study of urban expansion in Jordanian city using GIS and remote sensing. Int. J. Appl. Sci. Eng. 5(1), 41–52 (2007).

Kharazmi, R. et al. Monitoring and assessment of seasonal land cover changes using remote sensing: a 30-year (1987–2016) case study of Hamoun Wetland, Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190(6), 356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-018-6726-z (2018).

Ahukaemere, C. M., Ndukwu, B. N. & Agim, L. C. Soil quality and soil degradation as influenced by agricultural land use types in the humid environment. Int. J. For. Soil Eros. 2(4), 175–179 (2012).

Visser, S., Keesstra, S., Maas, G. & De Cleen, M. Soil as a basis to create enabling conditions for transitions towards sustainable land management as a key to achieve the SDGs by 2030. Sustainability 11(23), 6792 (2019).

Baranian Kabir, E., Bashari, H., Bassiri, M. & Mosaddeghi, M. R. Effects of land-use/cover change on soil hydraulic properties and pore characteristics in a semi-arid region of central Iran. Soil Tillage Res. 197, 104478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.still.2019.104478 (2020).

Mohammed, S., Kbibo, I., Alshihabi, O. & Mahfoud, E. Studying rainfall changes and water erosion of soil by using the WEPP model in Lattakia, Syria. J. Agric. Sci. Belgrade 61(4), 375–386 (2016).

Asadi, H., Honarmand, M., Vazifedoust, M. & Mousavi, A. Assessment of changes in soil erosion risk using RUSLE in Navrood Watershed, Iran. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 19, 231–244 (2017).

Hosseinalizadeh, M. et al. A Review on the Gully Erosion and Land Degradation in Iran in Gully Erosion Studies from India and Surrounding Regions (eds. Shit, P., Pourghasemi, H., & Bhunia, G.) 393–403 (Cham, 2020).

Jiang, L. et al. Assessing land degradation and quantifying its drivers in the Amudarya River delta. Ecol. Ind. 107, 105595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105595 (2019).

Mohammed, S. et al. Predicting soil erosion hazard in Lattakia governorate (W Syria). Int. J. Sedim. Res. 36(2), 207–220 (2020).

Mohammed, S. et al. Soil management effects on soil water erosion and runoff in central syria—a comparative evaluation of general linear model and random forest regression. Water 12(9), 2529 (2020).

Mohammed, S. et al. Estimating human impacts on soil erosion considering different hillslope inclinations and land uses in the coastal region of Syria. Water 12(10), 2786 (2020).

Katra, I. Soil erosion by wind and dust emission in semi-arid soils due to agricultural activities. Agronomy 10(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy10010089 (2020).

Mahala, A. Land Degradation Processes of Silabati River Basin, West Bengal, India: A Physical Perspective in Gully Erosion Studies from India and Surrounding Regions (eds. Shit, P. K., Pourghasemi, H. R. & Bhunia, G. S.) 265–278 (Cham, 2020).

Benavidez, R., Jackson, B., Maxwell, D. & Norton, K. A review of the (Revised) Universal Soil Loss Equation ((R)USLE): with a view to increasing its global applicability and improving soil loss estimates. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 22(11), 6059–6086 (2018).

Falcão, C. J. L. M., Duarte, S. M. D. A. & da SilvaVeloso, A. Estimating potential soil sheet Erosion in a Brazilian semiarid county using USLE, GIS, and remote sensing data. Environ. Monit. Assess. 192(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-019-7955-5 (2020).

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Keesstra, S. & Cerdà, A. Soil erosion as an environmental concern in vineyards: the case study of Celler del Roure, Eastern Spain, by means of rainfall simulation experiments. Beverages 4, 31 (2018).

López-Vicente, M., Calvo-Seas, E., Álvarez, S. & Cerdà, A. Effectiveness of cover crops to reduce loss of soil organic matter in a rainfed vineyard. Land 9, 230 (2020).

Abdo, H. G. Impacts of war in Syria on vegetation dynamics and erosion risks in Safita area, Tartous, Syria. Reg. Environ. Change 18(6), 1707–1719 (2018).

Gayen, A., Saha, S. & Pourghasemi, H. R. Soil erosion assessment using RUSLE model and its validation by FR probability model. Geocarto Int. 35(15), 1750–1768. https://doi.org/10.1080/10106049.2019.1581272 (2019).

Tsegaye, K., Addis, H. K. & Hassen, E. E. Soil erosion impact assessment using USLE/GIS approaches to identify high erosion risk areas in the lowland agricultural watershed of Blue Nile Basin, Ethiopia. Int. Ann. Sci. 8(1), 120–129. https://doi.org/10.21467/ias.8.1.120-129 (2019).

Panagos, P. et al. Towards estimates of future rainfall erosivity in Europe based on REDES and WorldClim datasets. J. Hydrol. 548, 251–262 (2017).

Gholami, V., Booij, M. J., Nikzad Tehrani, E. & Hadian, M. A. Spatial soil erosion estimation using an artificial neural network (ANN) and field plot data. CATENA 163, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2017.12.027 (2018).

Wischmeier, W.H., & Smith, D. D. Predicting rainfall erosion losses from cropland east of the Rocky Mountains: guide for selection for practices for soil and water conservation no. 282, 1–47 (Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 1965).

Wischmeier, W. H., & Smith, D. D. Predicting Rainfall Erosion Losses. A Guide to Conservation Planning. Agricultural Handbook no. 537, 285–291 (US Department of Agriculture, Washington, DC, 1978).

Stefanidis, S. & Stathis, D. Effect of climate change on soil erosion in a mountainous mediterranean catchment (Central Pindus, Greece). Water 10(10), 1469. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10101469 (2018).

Phinzi, K. & Ngetar, N. S. The assessment of water-borne erosion at catchment level using GIS-based RUSLE and remote sensing: a review. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 7(1), 27–46 (2019).

Aslan, Z., Erdemir, G., Feoli, E., Giorgi, F. & Okcu, D. Effects of climate change on soil erosion risk assessed by clustering and artificial neural network. Pure Appl. Geophys. 176(2), 937–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-018-2010-y (2019).

Azimi Sardari, M. R., Bazrafshan, O., Panagopoulos, T. & Sardooi, E. R. Modeling the impact of climate change and land use change scenarios on soil erosion at the Minab Dam Watershed. Sustainability 11(12), 3353. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11123353 (2019).

Tan, M. L., Yusop, Z., Chua, V. P. & Chan, N. W. Climate change impacts under CMIP5 RCP scenarios on water resources of the Kelantan River Basin, Malaysia. Atmos. Res. 189, 1–10 (2017).

Nilawar, A. P. & Waikar, M. L. Impacts of climate change on streamflow and sediment concentration under RCP 4.5 and 8.5: a case study in Purna river basin, India. Sci. Total Environ. 650, 2685–2696 (2019).

Teng, H. et al. Current and future assessments of soil erosion by water on the Tibetan Plateau based on RUSLE and CMIP5 climate models. Sci. Total Environ. 635, 673–686 (2018).

Chuenchum, P., Xu, M. & Tang, W. Predicted trends of soil erosion and sediment yield from future land use and climate change scenarios in the Lancang-Mekong River by using the modified RUSLE model. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 8(3), 213–227 (2020).

de Hipt, F. O. et al. Modeling the impact of climate change on water resources and soil erosion in a tropical catchment in Burkina Faso, West Africa. CATENA 163, 63–77 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Assessment of soil erosion risk and its response to climate change in the mid-Yarlung Tsangpo River region. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27(1), 607–621 (2020).

Jafari, R. & Bakhshandehmehr, L. Quantitative mapping and assessment of environmentally sensitive areas to desertification in central Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 27(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.2227 (2016).

Bahrami, A., Emadodin, I., Ranjbar Atashi, M. & Rudolf Bork, H. Land-use change and soil degradation: a case study, North of Iran. Agric. Biol. J. N. Am. 1(4), 600–605 (2010).

Emadi, M. & Baghernejad, M. Comparison of spatial interpolation techniques for mapping soil pH and salinity in agricultural coastal areas, northern Iran. Arch. Agron. Soil Sci. 60(9), 1315–1327 (2014).

Nabiollahi, K., Taghizadeh-Mehrjardi, R., Kerry, R. & Moradian, S. Assessment of soil quality indices for salt-affected agricultural land in Kurdistan Province, Iran. Ecol. Ind. 83, 482–494 (2017).

Nael, M., Khademi, H. & Hajabbasi, M. A. Response of soil quality indicators and their spatial variability to land degradation in central Iran. Appl. Soil. Ecol. 27(3), 221–232 (2004).

Emadodin, I. & Bork, H. R. Degradation of soils as a result of long-term human-induced transformation of the environment in Iran: an overview. J. Land Use Sci. 7(2), 203–219 (2012).

Gholami, H., Telfer, M. W., Blake, W. H. & Fathabadi, A. Aeolian sediment fingerprinting using a Bayesian mixing model: aeolian sediment fingerprinting using a Bayesian mixing model. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 42(14), 2365–2376. https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4189 (2017).

Javidan, N., Kavian, A., Pourghasemi, H. R., Conoscenti, C. & Jafarian, Z. Gully erosion susceptibility mapping using multivariate adaptive regression splines—replications and sample size scenarios. Water 11(11), 2319. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11112319 (2019).

Kenneth, G. R., George, R. F., Glenn, A. W. & Jeffrey, P. P. RUSLE: Revised universal soil loss equation. J. Soil Water Conserv. 46, 30–33 (1991).

Arekhi, S., Darvishi, A., Shabani, A., Fathizad, H. & Ahmadai Abchin, S. Mapping soil erosion and sediment yield susceptibility using RUSLE, remote sensing and GIS (Case study: Cham Gardalan Watershed, Iran). J. Adv. Environ. Biol 6(1), 109–124 (2012).

Kavian, A. et al. Effectiveness of vegetative buffer strips at reducing runoff, soil erosion, and nitrate transport during degraded hillslope restoration in northern Iran. Land Degrad. Dev. 29(9), 3194–3203. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3051 (2018).

Kavian, A. et al. Effectiveness of native wood strand mulches for land rehabilitation in Iran under experimental conditions. Land Degrad. Dev. 31(5), 581–590. https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.3473 (2020).

Mohammadi, M., Fallah, M., Kavian, A., Gholami, L. & Omidvar, E. The Application of RUSLE model in spatial distribution determination of soil loss hazard. Iran. J. EcoHydrol. 3(4), 645–658 (2017).

Ostovari, Y., Ghorbani-Dashtaki, S., Bahrami, H.-A., Naderi, M. & Dematte, J. A. M. Soil loss estimation using RUSLE model, GIS and remote sensing techniques: a case study from the Dembecha Watershed, Northwestern Ethiopia. Geoderma Reg. 11, 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geodrs.2017.06.003 (2017).

Arabameri, A., Lee, S., Tiefenbacher, J. P. & Ngo, P. T. T. Novel ensemble of MCDM-artificial intelligence techniques for groundwater-potential mapping in arid and semi-arid regions (Iran). Remote Sens. 12(3), 490 (2020).

Pourghasemi, H. R., Sadhasivam, N., Kariminejad, N. & Collins, A. Gully erosion spatial modelling: role of machine learning algorithms in selection of the best controlling factors and modelling process. Geosci. Front. 11(6), 2207–2219 (2020).

Emadodin, I., Taravat, A. & Rajaei, M. Effects of urban sprawl on local climate: a case study, north central Iran. Urban Clim. 17, 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.uclim.2016.08.008 (2016).

Hateffard, F., Dolati, P., Heidari, A. & Zolfaghari, A. A. Assessing the performance of decision tree and neural network models in mapping soil properties. J. Mt. Sci. 16(8), 1833–1847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11629-019-5409-8 (2019).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 37(12), 4302–4315. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Hijmans, R. J., Cameron, S. E., Parra, J. L., Jones, P. G. & Jarvis, A. Very high-resolution interpolated climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 25(15), 1965–1978. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.1276 (2005).

Doulabian, S., Golian, S., Toosi, A. S. & Murphy, C. Evaluating the effects of climate change on precipitation and temperature for Iran using RCP scenarios. J. Water Clim. Change https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2020.114 (2020).

Ostad-Ali-Askari, K., Ghorbanizadeh Kharazi, H., Shayannejad, M. & Zareian, M. J. Effect of climate change on precipitation patterns in an arid region using GCM models: case study of Isfahan-Borkhar Plain. Nat. Hazard. Rev. 21(2), 04020006. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)NH.1527-6996.0000367 (2020).

Renard, K. G. Predicting soil erosion by water: a guide to conservation planning with the Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE). United States Government Printing (1997).

Ghosal, K. & Das Bhattacharya, S. A review of RUSLE model. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 48, 689–707. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12524-019-01097-0 (2020).

Abdo, H. & Salloum, J. Mapping the soil loss in Marqya basin: Syria using RUSLE model in GIS and RS techniques. Environmental Earth Sciences 76(3), 114 (2017).

Abdo, H. & Salloum, J. Spatial assessment of soil erosion in Alqerdaha basin (Syria). Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 3(1), 26 (2017).

Mohammed, S. et al. Estimation of soil erosion risk in southern part of Syria by using RUSLE integrating geo informatics approach. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 20, 100375 (2020).

Duulatov, E. et al. Projected rainfall erosivity over Central Asia based on CMIP5 climate models. Water 11(5), 897. https://doi.org/10.3390/w11050897 (2019).

Abdo, H. G. Evolving a total-evaluation map of flash flood hazard for hydro-prioritization based on geohydromorphometric parameters and GIS–RS manner in Al-Hussain river basin, Tartous. Syria. Nat. Hazards 104(1), 681–703 (2020).

Arnoldus, H. M. J. An approximation of the rainfall factor in the Universal Soil Loss Equation in Assessment of erosion (eds. De Boodt, M. & Gabriels, D.) 127–132 (Chichester, 1980).

Fu, B. et al. Assessing the soil erosion control service of ecosystems change in the Loess Plateau of China. Ecol. Complex 8(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecocom.2011.07.003 (2011).

Prasannakumar, V., Vijith, H., Abinod, S. & Geetha, N. Estimation of soil erosion risk within a small mountainous sub-watershed in Kerala, India, using Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) and geo-information technology. Geosci. Front. 3(2), 209–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gsf.2011.11.003 (2012).

Shit, P. K., Nandi, A. S. & Bhunia, G. S. Soil erosion risk mapping using RUSLE model on jhargram sub-division at West Bengal in India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 1(3), 28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40808-015-0032-3 (2015).

Atoma, H., Suryabhagavan, K. V. & Balakrishnan, M. Soil erosion assessment using RUSLE model and GIS in Huluka watershed, Central Ethiopia. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 6(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-020-00365-z (2020).

Zhu, M. et al. Spatial and temporal characteristics of soil conservation service in the area of the upper and middle of the Yellow River, China. Heliyon 5(12), e02985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02985 (2019).

Abdo, H. G. Geo-modeling approach to predicting of erosion risks utilizing RS and GIS data: a case study of Al-Hussain Basin, Tartous, Syria. J. Environ. Geol. 1(1), 1–4 (2017).

Sharpley, A. N., & Williams, J. R. EPIC-Erosion/Productivity Impact Calculator. I: Model documentation. II: User manual. EPIC-Erosion/Productivity Impact Calculator. I: Model Documentation. II: User Manual, 1768 (1990).

Moore, I. D. & Burch, G. J. Modelling erosion and deposition: topographic effects. Trans. ASAE 29(6), 1624–1630. https://doi.org/10.13031/2013.30363 (1986).

Moore, I. D. & Burch, G. J. Physical basis of the length-slope factor in the universal soil loss equation. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 50(5), 1294–1298. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj1986.03615995005000050042x (1986).

Hou, X., Shao, J., Chen, X., Li, J. & Lu, J. Changes in the soil erosion status in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River basin from 2001 to 2014 and the impacts of erosion on the water quality of lakes and reservoirs. Int. J. Remote Sens. 41(8), 3175–3196. https://doi.org/10.1080/01431161.2019.1699974 (2020).

Li, G. et al. Temperature dependence of basalt weathering. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 443, 59–69 (2016).

Van der Knijff, J., Jones, R. & Montanarella, L. Soil erosion risk: assessment in Europe (Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 2000).

Mirakhorlo, M. S. & Rahimzadegan, M. Evaluating estimated sediment delivery by Revised Universal Soil Loss Equation (RUSLE) and Sediment Delivery Distributed (SEDD) in the Talar Watershed, Iran. Front. Earth Sci. 14(50–62), 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11707-019-0774-8 (2020).

Zare, M., Panagopoulos, T. & Loures, L. Simulating the impacts of future land use change on soil erosion in the Kasilian watershed, Iran. Land Use Policy 67, 558–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2017.06.028 (2017).

Nyesheja, E. M. et al. Soil erosion assessment using RUSLE model in the Congo Nile Ridge region of Rwanda. Phys. Geogr. 40(4), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723646.2018.1541706 (2019).

Pham, T. G., Nguyen, H. T. & Kappas, M. Assessment of soil quality indicators under different agricultural land uses and topographic aspects in Central Vietnam. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 6(4), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2018.08.001 (2018).

Morgan, R. P. C. Soil erosion and conservation (Wiley, 2009).

Moges, D. M., Kmoch, A., Bhat, H. G. & Uuemaa, E. Future soil loss in highland Ethiopia under changing climate and land use. Reg. Environ. Change 20(1), 1–14 (2020).

Ekhtesasi, M. R. & Sepehr, A. Investigation of wind erosion process for estimation, prevention, and control of DSS in Yazd-Ardakan plain. Environ. Monit. Assess. 159(1–4), 267 (2009).

Amiri, F. estimate of erosion and sedimentation in semi-arid Basin using empirical Models of erosion potential within a Geographic Information system. Air Soil Water Res. 3(1), 37–44 (2020).

Melo, J. A. Soil loss prediction by an integrated system using RUSLE, GIS and remote sensing in semi-arid region. Geoderma Reg. 11, 28–36 (2017).

Vaezi, A. R., Bahrami, H. A., Sadeghi, S. H. & Mahdian, M. H. Spatial variability of soil erodibility factor (K) of the USLE in North West of Iran. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 12, 241–252 (2010).

Behzadfar, M., Curovic, M., Simunic, I., Tanaskovik, V., & Spalevic, V. Calculation of soil erosion intensity in the S5-2 Watershed of the Shirindareh River Basin, Iran. In International Conference on Soil, Tirana, 5. (2015).

Khajavi, E., ArabKhedri, M., Mahdian, M. H. & Shadfar, S. Investigation of water erosion and soil loss values with using the measured data from Cs-137 method and experimental plots in Iran. J. Watershed Manag. Res. 6(11), 137–151 (2015) ((in Persian)).

Zakerinejad, R. & Maerker, M. An integrated assessment of soil erosion dynamics with special emphasis on gully erosion in the Mazayjan basin, southwestern Iran. Nat. Hazards 79(1), 25–50 (2015).

Rahimi, M. R., Ayoubi, S. & Abdi, M. R. Magnetic susceptibility and Cs-137 inventory variability as influenced by land use change and slope positions in a hilly, semiarid region of west-central Iran. J. Appl. Geophys. 89, 68–75 (2013).

Abbaszadeh Afshar, F., Ayoubi, S. & Jalalian, A. Soil redistribution rate and its relationship with soil organic carbon and total nitrogen using 137Cs technique in a cultivated complex hillslope in western Iran. J. Environ. Radioact. 101(8), 606–614 (2010).

Gericke, A., Kiesel, J., Deumlich, D. & Venohr, M. Recent and future changes in rainfall erosivity and implications for the soil erosion risk in brandenburg, ne germany. Water 11(5), 904 (2019).

Nearing, M. A., Pruski, F. F. & Oneal, M. R. Expected climate change impacts on soil erosion rates: a review. J. Soil Water Conserv. 59(1), 43–50 (2004).

Wang, B., Zheng, F. & Guan, Y. Improved USLE-K factor prediction: a case study on water erosion areas in China. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 4(3), 168–176 (2016).

Beretta-Blanco, A. & Carrasco-Letelier, L. USLE/RUSLE K-factors allocated through a linear mixed model for Uruguayan soils. Int. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 44(1), 100–112 (2017).

Cooper, T. H. Principles and applications of soil geography. Geoderma 33, 346–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7061(84)90035-1 (1984).

Ibáñez, J. J., Zinck, J. A. & Dazzi, C. Soil geography and diversity of the European biogeographical regions. Geoderma 192, 142–153 (2013).

Rodrigo-Comino, J. et al. Soil science challenges in a New Era: a transdisciplinary overview of relevant topics. Air Soil Water Res. 13, 1178622120977491 (2020).

Fathizad, H., Karimi, H. & Alibakhshi, S. M. The estimation of erosion and sediment by using the RUSLE model and RS and GIS techniques (Case study: Arid and semi-arid regions of Doviraj, Ilam province, Iran). Int. J. Agric. Crop Sci. 7(6), 303 (2014).

Yavuz, M. & Tufekcioglu, M. Estimating surface soil losses in the mountainous semi-arid watershed using RUSLE and geospatial technologies. Fresenius Environ. Bull. 28(4), 2589–2598 (2019).

de Carvalho Junior, W. et al. A regional-scale assessment of digital mapping of soil attributes in a tropical hillslope environment. Geoderma 232, 479–486 (2014).

Emadodin, I., Reinsch, T. & Taube, F. Drought and desertification in Iran. Hydrology 6(3), 66 (2019).

Almagro, A. et al. Improving cover and management factor (C-factor) estimation using remote sensing approaches for tropical regions. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 7, 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iswcr.2019.08.005 (2019).

Karpilo Jr, R. D., & Toy, T. J. Rusle C-factors for slope protection applications. In Proceedings America Society of Mining and Reclamation, 995–1013 (2004).

Panagos, P. et al. Modelling the effect of support practices (P-factor) on the reduction of soil erosion by water at European scale. Environ. Sci. Policy 51, 23–34 (2015).

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Silva, A. M. D., Moradi, E., Terol, E. & Cerdà, A. Improved Stock Unearthing Method (ISUM) as a tool to determine the value of alternative topographic factors in estimating inter-row soil mobilisation in citrus orchards. Span. J. Soil Sci 10(1), 65–80 (2020).

Cammeraat, E., van Beek, R. & Kooijman, A. Vegetation succession and its consequences for slope stability in SE Spain. Plant Soil 278, 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-005-5893-1 (2005).

Sadoddin, S. H. R. A., & Najafinejad, A. Progressive Watershed Management Approaches in Iran in Proceedings of 19th International Conference on Natural Resources Management and Ecosystems, 2–3 (2017).

Sadeghi, S. H., Abdollahi, Z. & Darvishan, A. K. Experimental comparison of some techniques for estimating natural raindrop size distribution on the south coast of the Caspian Sea, Iran. Hydrol. Sci. J. 58(6), 1374–1382 (2013).

Borrelli, P. et al. Land use and climate change impacts on global soil erosion by water (2015–2070). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 117(36), 21994–22001 (2020).

Yigini, Y. & Panagos, P. Assessment of soil organic carbon stocks under future climate and land cover changes in Europe. Sci. Total Environ. 557, 838–850 (2016).

Yu, O. T. et al. Precipitation events and management practices affect greenhouse gas emissions from vineyards in a Mediterranean climate. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 81, 138–152. https://doi.org/10.2136/sssaj2016.04.0098 (2017).

Nadal-Romero, E., Cortesi, N. & González-Hidalgo, J. C. Weather types, runoff and sediment yield in a Mediterranean mountain landscape. Earth Surf. Proc. Land. 39(4), 427–437 (2014).

Alewell, C., Borrelli, P., Meusburger, K. & Panagos, P. Using the USLE: Chances, challenges and limitations of soil erosion modelling. Int. Soil Water Conserv. Res. 7(3), 203–225 (2019).

Ayoubi, S., Mokhtari, J., Mosaddeghi, M. R. & Zeraatpisheh, M. Erodibility of calcareous soils as influenced by land use and intrinsic soil properties in a semiarid region of central Iran. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190(4), 192 (2018).

Bagarello, V. Effective practices in mitigating soil erosion from fields. Oxf. Res. Encycl. Environ. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.242 (2017).

Marques, M., Ruiz-Colmenero, M., Bienes, R., García-Díaz, A. & Sastre, B. Effects of a permanent soil cover on water dynamics and wine characteristics in a steep vineyard in the Central Spain. Air Soil Water Res. 13, 1178622120948069. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178622120948069 (2020).

Rodrigo-Comino, J., Terol, E., Mora, G., Gimenez-Morera, A. & Cerdà, A. Vicia sativa Roth. can reduce soil and water losses in recently planted vineyards (Vitis vinifera L.). Earth Syst. Environ., https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-020-00191-5 (2020).

Mohammed, S. et al. Impacts of rainstorms on soil erosion and organic matter for different cover crop systems in the western coast agricultural region of Syria. Soil Use Manag. 37, 196–213 (2021).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.; Data curation and collection, A.H., F.H. and K.A.; Visualization (mapping), K.A., and F.H; Writing—original draft, S.M., and H.G.A.; Writing—review and editing, G.E, A.H., K.A, J.C., F.H. H.G.A., and S.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hateffard, F., Mohammed, S., Alsafadi, K. et al. CMIP5 climate projections and RUSLE-based soil erosion assessment in the central part of Iran. Sci Rep 11, 7273 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86618-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86618-z

This article is cited by

-

Challenges of rainfall erosivity prediction: A Novel GIS-Based Optimization algorithm to reduce uncertainty in large country modeling

Earth Science Informatics (2024)

-

Implementation of random forest, adaptive boosting, and gradient boosting decision trees algorithms for gully erosion susceptibility mapping using remote sensing and GIS

Environmental Earth Sciences (2024)

-

Modeling the impacts of projected climate change on wheat crop suitability in semi-arid regions using the AHP-based weighted climatic suitability index and CMIP6

Geoscience Letters (2023)

-

Predicting soil erosion potential under CMIP6 climate change scenarios in the Chini Lake Basin, Malaysia

Geoscience Letters (2023)

-

Relation of land surface temperature with different vegetation indices using multi-temporal remote sensing data in Sahiwal region, Pakistan

Geoscience Letters (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.