Abstract

Mussels, which occupy important positions in marine ecosystems, attach tightly to underwater substrates using a proteinaceous holdfast known as the byssus, which is tough, durable, and resistant to enzymatic degradation. Although various byssal proteins have been identified, the mechanisms by which it achieves such durability are unknown. Here we report comprehensive identification of genes involved in byssus formation through whole-genome and foot-specific transcriptomic analyses of the green mussel, Perna viridis. Interestingly, proteins encoded by highly expressed genes include proteinase inhibitors and defense proteins, including lysozyme and lectins, in addition to structural proteins and protein modification enzymes that probably catalyze polymerization and insolubilization. This assemblage of structural and protective molecules constitutes a multi-pronged strategy to render the byssus highly resistant to environmental insults.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

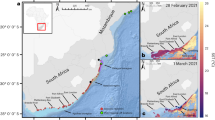

Mussels of the bivalve family Mytilidae occur in a variety of environments from freshwater to deep-sea. The family incudes ecologically important taxa such as coastal species of the genera Mytilus and Perna, the freshwater mussel, Limnoperna fortuneri, and deep-sea species of the genus Bathymodiolus, which constitute keystone species in their respective ecosystems1. One of the most important characteristics of mussels is their capacity to attach to underwater substrates using a structure known as the byssus, a proteinous holdfast consisting of threads and adhesive plaques (Fig. 1)2. Using the byssus, mussels often form dense clusters called “mussel beds.” The piled-up structure of mussel beds enables mussels to support large biomass per unit area, and also creates habitat for other species in these communities3,4. The capacity of the byssus to attach to a wide variety of surfaces also enables mussels to expand their habitats by utilizing less competitive surfaces, including artificial underwater constructs such as piers, quay walls, and aquaculture nets5. Thus, the byssus is essential to the unique lifestyle of mussels and their roles in marine and freshwater ecosystems.

Components of the byssus have been studied for more than 40 years, and major components, including several collagens, and structural and cuticle proteins, designated as foot proteins (fps), have been discovered mainly in Mytilus spp.2,6. Gradient distribution of different types of collagens with silk-like (Col-D) and elastic (Col-P) domains as well as a connecting collagen (Col-NG) have been discovered7. Six major types of fps (fp-1 to -6) have been discovered and each contains post-translationally modified amino acid residues such as Dopa (3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine), hydroxyproline, hydroxyarginine, and phosphoserine2,6. Although such amino acid modifications, especially the crosslinking of Dopa residues, are thought to be involved in polymerization and insolubilization of fps, detailed functions have yet to be confirmed2. Moreover, expansion of these analyses to other mussel species suggest that byssus formation mechanisms are unexpectedly diverse among species. For example, fp-1 from the green mussel, Perna viridis (Pvfp-1), less dependent on Dopa-related crosslinking8,9, although the corresponding protein of Myilus edulis (Mefp-1) contains many Dopa residues2.

In this study, we performed whole genome sequencing of the green mussel, P. viridis (Fig. 1) to understand physiological systems comprehensively, including byssus formation. The green mussel is a dominant species in Asian tropical and subtropical coastal areas10,11,12, but is also expanding its distribution as an invasive species, even in North and South America13,14,15,16,17. The green mussel is a keystone species of coastal ecosystems, forming mussel beds of large biomass and actively ingesting suspended materials and plankton in the water by filter-feeding. In so doing, it transfers the constituents of ingested organisms and their metabolites to organisms higher in the food chain16,18. The green mussel is also a major food resource for humans, and is actively cultured in many countries10,11. In addition, the green mussel is relatively tolerant of anthropogenic chemical pollutants, concentrating them in the body11. It has been proposed as an effective vehicle to monitor environmental pollution19,20,21,22. Thus, whole genome sequencing of this species is expected to contribute to understanding of its ecology, physiology, and the ecosystems it inhabits.

In this study, we report the high-quality assembly and annotation of whole genome sequences of the green mussel. We also collected transcriptomic data from six major tissues, including the foot, and selected genes expressed at significantly higher levels in the foot than in five other tissues, based on Z-scores. Using genome sequence information with the transcriptomic data, we identified genes involved in byssus formation. Although transcriptomic and proteomic studies have been reported in this species previously23,24, the combination of genomic and foot-specific transcriptomic analyses were expected to yield information specific to characteristics of the byssus. After confirming that our data contained genes encoding known fps and collagens, we listed genes exclusively expressed in the foot, the site of byssus production, to find more components involved in byssus formation. As the list included various proteinase inhibitors, defense proteins, and lectins, in addition to structural proteins, such as fps and collagens and their processing enzymes, we propose that byssus formation includes not only construction of resilient structures, but also genes for protection of the byssus.

Results and discussion

Results of the sequencing and assembly

A wild green mussel collected in Enoshima, Kanagawa, Japan was used for genome sequencing. By sequencing one paired-end library and 4 mate-paired libraries using an Illumina HiSeq2500 platform, trimmed sequences were obtained (Supplementary Table S1). Analyses of Illumina data with Genome Scope25 estimated the genome size at 726 Mb (Supplementary Fig. S1), which is less than half the size of genomes from other mussel species, Mytilus galloprovincialis (1.28 Gb), Mytilus coruscus (1.90 Gb), Bathymodiolus platifrons (1.66 Gb), Modiolus philippinarum (2.63 Gb), and L. fortunei (1.67 Gb)26,27,28,29. Genome Scope also estimated heterozygosity at 0.63%, and repetitive portions of the genome at 19.57% (Supplementary Fig. S1). The low heterozygosity may represent a founder effect, since the sampling site, Enoshima, was first colonized by this species only in 198830, and the population may have developed from a limited number of individuals. Sequences were assembled into 15,933 scaffolds (Table 1), of which the longest was 25,893,196 bp. The N50 size was 4,106,945 bp. These statistics suggest that the contiguity of this genome surpasses those of other mussel species (Table 1). From the assembled genome sequences, 24,293 genes were predicted. This predicted gene number was lower than those of other mussel species (Table 2). We think that this is mainly because many predicted genes are disrupted in these species due to fragmented genomes. In fact, the total exon length was comparable to those of B. platifrons and M. philippinarum (Table 2) and the predicted gene number (24,293) is comparable to those of scallops and oysters (24,521 and 29,738, respectively)31,32. The total intron length was shorter than those of the two foregoing species, which may reflect the smaller genome size. Evaluation of genome assembly and gene prediction completeness with Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO)33 using 978 metazoan genes, scored 99.4%, indicating high completeness of the assembly and annotation (Table 3).

Domains amplified in the green mussel genome

According to the method reported in a previous study27, Pfam domains whose numbers are increased in the green mussel genome were searched. As a result, numbers of six domains, lectin C-type domain, WAP (Whey Acidic Protein)-type 'four-disulfide core', extracellular link domain, dual specificity phosphatase catalytic domain, KR domain, and tyrosine phosphatase family domain were found increased (Supplementary Table S2). The significance of the domains with increased number will be discussed below.

Phylogenetic analyses using orthogroups

Annotated genomes are available for 11 mollusk species (Supplementary Table S3), and a relatively high number of genes are predicted from them. Using those 11 genomes, with genomes of two insects (Tribolium castaneum and Drosophila melanogaster) as outgroups, orthologous group (OG) clustering was performed using OrthoFinder and resulted in 21,139 orthogroups (OGs) from the 13 genomes. Within the 21,139 OGs, 845 single-copy OGs were selected for phylogenomic analysis. Among them, using 805 OGs in which 30 or more amino acids were successfully aligned, phylogenetic analysis was performed (Fig. 2a). As a result, a maximum likelihood (ML) tree with high bootstrap support was constructed. The tree indicates that bivalves are more closely related to gastropods than to cephalopods. Among the hypotheses regarding mollusk phylogeny, our results support the Aculifera-Conchifera hypothesis34,35,36. The phylogeny of Mytilids is also of interest. A phylogenetic tree, including recently published data of Mytilus galloprovincialis and M. coruscus, was constructed using an alignment of 153 single-copy OGs (Fig. 2b). The result clearly indicated that position Perna is phylogenetically closer to Mytilus than to other genera, including Bathymodiolus, Modiolus, and Limnoperna. The present result is consistent with phylogeny based on mitochondrial and ribosomal DNA, and transcriptome sequences reported previously27,37,38, although the position of Limnoperna is inconsistent with a transcriptomic tree reported previously27.

Maximum likelihood (ML) trees of mollusks and bivalves constructed using orthogroups developed from whole-genome sequences. (a) phylogenetic tree of mollusks, constructed using 805 genes selected from genome sequences. Tribolium castaneum and Drosophila melanogaster were used as outgroups. (b) phylogenetic tree of bivalves constructed using 153 genes selected from genome sequences. Lottia gigantea and Haliotis discus hannai were used as an outgroup. All nodes have 100% bootstrap support after 100 replications.

Search for byssal collagen genes

Three major pre-collagen genes reported by Zhang et al.23 were discovered among the genome scaffolds. Col-D and Col-NG genes were identified close together on the same scaffold (pvir_s00637g8 and pvir_s00637g10), suggesting generation of the two genes through tandem duplication (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3). Interestingly, pvir_s00637g9, the gene between the two collagen genes encodes a highly glycine-rich protein, but it is not a collagen because the glycine residues are not arranged in a characteristic G-X-Y repeat. Col-P23 corresponded to pvir_s00107g4, although there are some differences in predicted N- and C-terminal sequences (Supplementary Fig. S4).

Search for genes of known major fps

Genes encoding major fps reported in the green mussel, i.e., those for Pvfp-1 through -6 were searched in the green mussel genome scaffolds using previously reported sequences23,24 as queries (Table 4). Known sequences of Pvfp-1 were aligned to different parts of the protein encoded by a single gene, s00107g6, identified in this study (Supplementary Fig. S5). Fp-2 sequences previously identified (AGZ84282) corresponded to the carboxyl terminal part of the protein encoded by pvir_s01028g36 (Supplementary Fig. S6). The whole coding region of Pvfp-2 predicted in this study encoded 23 EGF-like repeats (Supplementary Fig. S7a). A fp-3 sequence, AGZ84284, previously reported, was completely matched to part of the protein encoded by pvir_s136476g25 (Supplementary Fig. S8). Other known fp-3 sequences, AGZ84285, and GGRR01022672, also corresponded to the protein encoded by pvir_s136476g26. The neighboring gene, pvir_s136476g24 also encodes a similar protein (Supplementary Fig. S8). Thus, Pvfp-3 is likely to exist as a multiple copy gene, as suggested in M. galloprovincialis fp-339, and the copies were generated through tandem duplications. Pvfp-4, reported by Zhang et al.23 (GGRR01022802) almost matched the protein encoded by pvir_s00068g44 (Supplementary Fig. S9). Three genes, pvir_s001219b108, pvir_s001219g109, and s001219g110, arranged in tandem on the same scaffold, encode previously reported Pvfp-5 sequences (Table 4 and Supplementary Fig. S10). Thus, Pvfp-5 is a multicopy gene family generated by tandem duplications. Pvfp-6 reported in previous studies, GGRR01025060 and AGZ84283, matched pvir_s00010g6, except for two amino acid substitutions (Supplementary Fig. S11).

Dominant genes exclusively expressed in the foot.

The bivalve foot is a multifunctional organ that functions as a sensor and a locomotor organ. However, for mussels, byssus synthesis is its primary role, and much of the foot is occupied by glands that secrete byssal components and the ventral groove, which is a template for the byssus40. In addition, in Mytilus, genes for some byssal components are expressed exclusively in the foot41,42,43. Therefore, we compiled transcripts exclusively detected in the foot (Z-score > 1.96), which is the point of the present study, compared with previous foot-transcriptome studies in P. viridis and M. californianus23,24,44 and foot transcriptomic and proteomic studies in M. coruscus45. A list of foot-specifically expressed genes was arranged in descending order of Transcripts Per Million (TPM) (Supplementary Table S4). The top 81 genes were dominated by possible byssus-related genes, so we denominated them Highly Expressed genes in the Foot (HEFs). Most peptides encoded by HEFs are predicted to have signal peptides (Supplementary Table S4). Annotations of listed genes were searched against the Swiss-Prot database (Supplementary Table S4), and 39 HEFs were successfully annotated. HEFs with no hits were subjected to global BLAST and motif searches, and possible functions were predicted for an additional 20 genes. The remaining 22 genes could not be annotated. We categorized the 59 HEFs with annotations or probable functions into 6 groups: known and potential fps (23 genes), collagens and related proteins (7 genes), protein-processing proteins (2 gene), lectin-like proteins (9 genes), proteinase inhibitors (10 genes), biological defense-related proteins (5 genes), and others (3 genes) (Fig. 3). Details of each group are described below.

Known and potential fps: All known fp-genes described above (Table 4), except fp-4 with low TPM, were found among 90 HEFs. Many are annotated as Notch or (Proto)Cadherin or no hit by Swiss-Prot searches, because of the lack of mussel-specific genes in the database. Therefore, 10 other genes that are annotated as Notch- or Cadherin-like are categorized as potentially novel fp genes. Among them, two genes, pvir_s01028g37 and pvir_s00819g17 encode proteins consisting mainly of long EGF-like repeats with terminal peptides containing tyrosine residues (Supplementary Fig. S7b,c). Such characteristics are common in fp-2 of Mytilus41. Especially, the former is tandemly localized with pvir_s01028g36 encoding P. viridis fp-2 (Supplementary Fig. S7a); thus, it is likely to be an additional copy of fp-2 generated through tandem duplication, although the number of EGF-like repeats is different. As the other gene, pvir_s00819g17, encodes highly conserved repeats, it should be considered a different class from fp-2. Another 9 genes have structural characteristics similar to fp-5 s, i.e., they contain 1–7 EGF-like repeats (Supplementary Fig. S12). Phylogenetic analysis of these proteins with known fp-5 s (Supplementary Fig. S13) indicated that pvir_s01219g106 and pvir_s01219g107 are additional tandem copies of fp-5 genes. Other Pvfp-5-like proteins, encoded by scaffolds other than pvir_s01219, formed two separate clades: one includes two genes on pir_s00079 and the other comprises those on pvir_s00296, pvir_s02522, and pvir_s136446. Proteins encoded by these genes may be functionally independent from known Pvfp-5 s.

Collagens and related proteins: 7 genes were annotated as collagens using Swiss-Prot searches. Among the three major known collagens, Col-D and Col-NG exhibited the highest TPM values. However, pvir_s00107g4, encoding a known Col-P had low TPM. Its neighboring gene, pvir_s00107g5, also contained relatively short G-X-Y repeats and was identified as a proximal thread matrix protein (PTMP)23. Three tandem genes, pvir_s00096.g4, pvir_s00096.g5, and pvir_s00096.g6 were novel collagen genes, and they may be important for byssus formation, considering their high expression levels. One remaining gene was actually not a typical collagen because it encoded a protein without G-X-Y repeats. It was annotated as a collagen because it is similar to the non-G-X-Y part of a mammalian collagen; thus, it may interact with collagens.

Protein processing proteins: One gene was annotated as a peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, which constructs specific helical structures of collagens46,47. Protein transport protein (Sec61)-like genes were also included among HEFs.

Lectin-like proteins: 9 genes were annotated as C-type lectins or lectin domain-containing proteins. They may participate in biological defense mechanisms48, and they may also be involved in specific conformation of fps or collagens by regulating glycosylation, in cooperation with enzymes involved in sugar chain regulation. The sets of genes, pvir_s00346g40/pvir_s00346g41 and pvir_s00466g48/pvir_s00466g49, of which the latter accompanies one similar gene pvir_s00466g47 with lower TPM, were found in tandem, suggesting amplification by tandem duplication. Such amplification of lectin-like genes may be related to the amplification of C-type lectin domains (Supplementary Table S2).

Proteinase inhibitors: It is surprising that 10 proteinase inhibitors, including serine protease inhibitors and metalloprotease inhibitors, are included among HEFs, although transcripts for a serine protease inhibitor have been reported previously24. If these proteinase inhibitors are deposited in the byssus, they may protect it from attack by proteinases produced by bacteria and other organisms. The resistance of the byssus to various proteinases has been attributed to crosslinking and polymerization40. However, inclusion of proteinase inhibitors may be an additional reason. It is also possible that they protect byssal proteins until crosslinking and polymerization are complete, although it is still possible that these proteinase inhibitors may be protecting the foot tissue. Two HEFs, pvir_s00544g11 and pvir_s00884g60 were found to have WAP-type, four-disulfide core domains, which are amplified in the genome (Supplementary Table S2), but without significant annotation against SwissProt. These genes may encode novel important proteins.

Biological defense-related proteins: Five HEFs likely function in self-defense. The protein encoded by pvir_s00401g98 is similar to a Mytilus antimicrobial protein. Genes encoding lysozyme and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein are also supposed to be involved in anti-bacterial defense. A CD109-like molecule may also function in self-defense. pvir_s01169g96 encodes a protein containing CUB and sushi domains, which are involved in the complement cascade. Considering their specific expression in the foot, these molecules may be specialized for protection of the byssus.

Others: High levels of expression of ornithine decarboxylase antizyme, tubulin, and protein transport protein genes are of interest, but the degree of specificity of expression in the foot is not high. Expression of proteins similar to thrombospondin type-1 domain-containing protein in the foot is interesting, but it is difficult to speculate on their functions in the foot and further study is needed. In addition, 21 HEFs that could not be annotated are expected to be important for byssus formation and maintenance.

Genes expressed exclusively in the foot, but at lower levels.

Other genes in the same 6 categories, but less highly expressed than HEFs, were also identified (Supplementary Table S4). Among them, proteinase inhibitor-like genes were strongly detected, suggesting involvement of many genes to protect the byssus from proteolysis. Some such genes, for example, 11 genes on scaffold pvir_s00124, 4 genes on pvir_s00028, and 2 genes each on pvir_s00161 and pvir_s00234, were found clustered in tandem on the same scaffold, suggesting expansion via tandem duplications, perhaps to achieve bulk production. Eight copies of CD109 antigen-like genes, one of which is included among HEFs, were arranged in tandem on scaffold pvir_s00037.

Many potential enzyme genes are also present. Notably, 11 tyrosinase-like genes were identified. Four of them are on scaffold pvir00137, two are on pvir00219, and two are on pvir_00667, suggesting that tyrosinase genes have been tandemly duplicated. Tyrosinases are involved in Dopa formation and crosslinking processes; thus, they play central roles in byssus formation2, and their expansion is quite reasonable. Existence of multiple tyrosinase genes was also detected in the foot of M. coruscus in a proteomic analysis45.

In addition, a number of genes that are likely involved in byssal protein modification were identified. For example, prolyl 4-hydroxylase-like, protein disulfide-isomerase-like genes, and peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase-like genes, which promote collagen helix formation46,47, were included. Genes annotated as other enzymes, such as serine/threonine protein kinase, phenylalanine-4-hydroxylase, protein phosphatase, bifunctional arginine demethylase and lysyl-hydroxylase, and protein arginine N-methyltransferase are also potentially involved in metabolism and processing of byssal proteins. Moreover, numerous genes were annotated as sugar chain-modification enzymes, many of which act upon mannosyl residues. These genes are also likely involved in byssus formation or function, as the importance of glycosylation has been reported in green mussel fp-19,49, quagga mussel, Dreissena bugensis fp-150, and PTMP of M. galloprovincialis51. In addition, the importance of sugar-mediated binding has been reported in the byssus of the fan shell, Atrina pectinate52. Some potential sugar modification enzyme genes are also found duplicated in tandem. For example, pvir_s00101g48 and pvir_s00101g50, pvir_s00101g97 and pvir_s00101g99, and pvir_s00130g47 and pvir_s00130g48 are annotated as beta-1,3-galactosyltransferase, glycoprotein_3-alpha-L-fucosyltransferase, and glycosyltransferase-25-like genes, respectively (Supplementary Table S4). Such genes may have been amplified for bulk production. Notably, some peptide motifs in the green mussel genome (Supplementary Table S2) are probably related to protein processing.

Two genes annotated as superoxide dismutases (SOD) (pvir_s00007g27 and pvir_s00007g29), which are tandemly located in the genome, were also expressed exclusively in the foot (Supplementary Table S4). While 12 SOD-like genes were detected in the green mussel genome (Supplementary Table S5), 10 other genes were not foot-specific. Antioxidant activity is reportedly important for byssus formation, and fp-6 has antioxidant activity53. These two foot-specific SOD genes may contribute to formation of the byssus as antioxidants.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of foot-specific RNA-seq analysis suggest that two mechanisms are involved in creating a tough, durable byssus (Fig. 4). One is to employ resilient materials, including structural proteins such as collagens, fps, and TMPs, and modifying components, such as enzymes and lectins, to construct specific structures. The other mechanism is to protect byssal proteins against proteases and bacteria, in which defense proteins including lysozyme, proteinase inhibitors, and possibly lectins are involved. Previous studies on byssus formation mechanisms have focused mainly on the former. However, the number of genes involved in defense mechanisms identified in this study indicate that mussels devote considerable energy to the latter, which is likely the key to byssus durability. In addition, we propose that identification of genes expressed exclusively in the foot is a useful approach to study the complicated process of byssus formation and maintenance.

Strategy of the green mussel to form a tough, durable byssus, suggested by whole-genome and transcriptome analyses. Major genes expressed exclusively in the foot were classified into two major categories: genes encoding structural proteins (collagens, TMPs, and foot proteins) and processing proteins, including modification and polymerization enzymes and transport proteins, and those encoding proteins that protect the byssus from attack by bacteria and proteinases.

Methods

Mussels

Specimens of Perna viridis were collected at Enoshima, Fujisawa, Japan, on August 27, 2018, and maintained in a plastic tank at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, The University of Tokyo, using natural seawater, until use. Foot, gill, mantle, adductor muscle, and testes were dissected from a male specimen with a shell length of approximately 4 cm. Dissected tissues were kept at -80°C until DNA or RNA extraction.

Genomic DNA extraction, sequencing, and de novo assembly

Genomic DNA was extracted from the testis using a Mag attract HMW DNA kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA, USA). Paired-end (250 bp) and mate-pair libraries (3, 6, 10, and 15 kb) were constructed using a TruSeq DNA PCR-Free LT Sample Prep Kit and a Nextera Mate Pair Sample Prep Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Sequencing employed an Illumina HiSeq2500. We generated 731,873,830 bp of raw sequence data for de novo genome assembly. Genome assembly into scaffolds was performed using the Platanus v1.2.4 assembler54 after removal of adapter sequences (Platanus_trim and Platanus_internal_trim). Contig assembly was performed using only the PE library, and then scaffolding and gap closure were performed using all libraries. Genome Scope25 was used for genome size and heterozygosity analyses. Generated scaffolds were named in order of length as pvir_s00001, starting with the longest.

Gene annotation

Genes on genome scaffolds were predicted by combining RNA-seq-based prediction results, homology-based prediction results for related species, and ab initio prediction results. RNA-seq based prediction utilized both the assembly-first method and the mapping-first method. For the assembly-first method, RNA-seq data were assembled using Trinity55 and Oases56. Then, assembled contigs were splice-mapped with GMAP57. For the mapping-first method, RNA-seq data were mapped to genome scaffolds using HISAT258. Then gene sets were predicted with StringTie59 from mapped results. Details of RNA-seq data are described below. In terms of homology-based prediction, amino acid sequences of Patinopecten yessoensis, Lottia gigantea, Crassostrea giga, Modiolus philippinarum, Bathymodiolus platifrons, and Mytilus galloprovincialis26,31,32,60,61, were spliced-mapped to genome scaffolds using Spaln62, and gene sets were predicted. For ab initio prediction, first, training sets were selected from RNA-seq based prediction results. Then AUGUSTUS63 was trained using this set. SNAP64 was also used. Finally, all predicted genes were combined using an in-house merging tool. Predicted genes were functionally annotated with NCBI Swiss-Prot (October, 2019) using BLAST65 with an e-value cutoff of 1e−5. Each gene was named ‘g’ plus a number from one end of each scaffold, e.g., pvir_s00001.g1 is the first gene of scaffold pvir_s00001. Transcriptomic and proteomic completeness for each longest transcript were evaluated using BUSCO v3.0.233 with the metazoan dataset. Search for Pfam domains whose numbers are expanded in the green mussel genome were conducted as described previsouly27.

RNA extraction, sequencing, and expression level detection

Total RNA was extracted from seven tissues (adductor muscle, foot, gill, testis, intestine, kidney, and mantle) using TRIzol reagent, and each library was prepared using a TruSeq Standed mRNA prep kit (Illumina) and sequenced on a Nova Seq 6000 platform (Illumina) with 100-bp paired-ends by Macrogen Corporation, Japan. Low-quality reads (Q<20 and length <25 bp) were trimmed with CUTADAPT v1.1866. Then, cleaned reads were mapped to Perna gene models with SALMON v0.14.167 using default settings. Expression levels were expressed as transcripts per million (TPM).

Phylogenetic analysis

For comparison of orthologs, we used genomes of several metazoan species (Supplementary Table S3). Gene models of mussels (B. platifrons and M. philippinarum) were downloaded from DRYAD (https://datadryad.org)27. The genome of the pearl oyster (Pinctada fucata) was downloaded from the Genome browser of the Marine Genomics Unit at OIST (Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology) (https://marinegenomics.oist.jp/). Genomes of other taxa were downloaded from NCBI Reference Sequence (RefSeq). Gene models for genomes downloaded from GenBank assembly and RefSeq were generated with Gffread68 and were translated to amino acids using TransDecoder v5.5.069. Then, the longest transcript variant for each gene model was retained. Ortholog groups (OGs) with no gaps were identified from translated longest sequences using OrthoFinder v2.3.370 with default settings. Identified OGs were annotated with the human proteome, downloaded from Uni-Prot (October, 2019) or NCBI Swiss-Prot (October, 2019) using BLAST65 with e-value cutoff of 1e−5. All sequences were aligned using MAFFT v7.42971,72, and gaps in alignments were removed using trimAL v1.273. Then aligned amino acid sequences of each OG were concatenated. Maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were performed using RAxML v8.2.1174 with the PROTGAMMAAUTO option.

For comparison of orthologs from bivalves, we used protein sequences of 9 bivalves (P. viridis, P. yessoensis, C. gigas, P. fucata, L. fortunei, M. philippinarum, B. platifrons, M. galloprovincialis and M. coruscus) and 2 snails (Haliotis discus hannai, L. gigantea). Protein sequences of L. fortunei and H. discus hannai were downloaded from GigaDB (http://gigadb.org/). Identification of orthologous groups of proteins was performed as follows. First, protein sequences from all species were grouped into gene families and 153 ortholog groups were extracted with a one-to-one relationship across all species, using Proteinortho 75. For each group, multiple alignments were performed with MAFFT71 and sites containing gaps (“−”) or ambiguous characters (“X”) were excluded. All alignments were concatenated, and 34,223 amino acid sites were used for phylogenetic analysis. A phylogenetic tree was constructed with RAxML (version 8.2.12)74. Here, we applied the JTT substitution matrix with a gamma model of rate heterogeneity (-m PROTGAMMAJTT). The ML tree of fp-5-like sequences was also constructed using MAFFT71 and RAxML v8.2.1174 with the PROTGAMMAAUTO option.

Exploring putative byssal proteins

Putative foot protein genes in the genome assembly were searched with BLAST using previously reported Perna foot proteins23,24 and mussel foot proteins downloaded from NCBI.

Searching for genes exclusively expressed in the foot

TPMs of all genes were standardized using Z-scores across TPM over all organs. Predicted genes for which TPM counts in the foot were significantly higher than those of the other six organs were listed (Z-score > 1.96; Supplementary Table S4). From the listed genes, those with TPM counts higher than 550 were selected as HEFs. HEF genes with no hit against SwissProt were subjected to TBLASTN searches in the DNA Data Bank of Japan and Prosite (https://prosite.expasy.org/), using default settings. Signal peptides and motifs in fp-like proteins were identified using SignalP-5.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) and Prosite, respectively. SOD genes were picked up according to BLAST annotation against SwissProt.

Data availability

The Perna viridis genome sequence can be accessed at DDBJ and Bioproject (NCBI) as PRJDB10567, which links to the Sequence Read Archive for all genome raw and assembled scaffold (nucleotide) data under BioSamples SAMD00247165.

References

Lee, Y. et al. A mitochondrial genome phylogeny of Mytilidae (Bivalvia: Mytilida). Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 139, 106533 (2019).

Waite, J. H. Mussel adhesion—Essential footwork. J. Exp. Biol. 220, 517–530 (2017).

Engel, F. G. et al. Mussel beds are biological power stations on intertidal flats. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 191, 21–27 (2017).

Ricklefs, K., Buettger, H. & Asmus, H. Occurrence, stability, and associated species of subtidal mussel beds in the North Frisian Wadden Sea (German North Sea Coast). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 233, 106549 (2020).

Gilg, M. R. et al. Recruitment preferences of non-native mussels: Interaction between marine invasions and land-use changes. J. Mollusc. Stud. 76, 333–339 (2010).

Bandara, N., Zeng, H. & Wu, J. Marine mussel adhesion: Biochemistry, mechanisms, and biomimetics. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 27, 2139–2162 (2013).

Qin, X. & Waite, J. H. A potential mediator of collagenous block copolymer gradients in mussel byssal threads. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 10517–10522 (1998).

Hwang, D. S. et al. Adhesion mechanism in a DOPA-deficient foot protein from green mussels. Soft Matter 8, 5640 (2012).

Zhao, H., Sagert, J., Hwang, D. S. & Waite, J. H. Glycosylated hydroxytryptophan in a mussel adhesive protein from Perna viridis. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 23344–23352 (2009).

Siddall, S. E. A clarification of the genus Perna (Mytilidae). Bull. Mar. Sci. 30, 858–870 (1980).

Gosling, E. M. Bivalve Molluscs: Biology, Ecology and Culture (Blackwell, 2003).

Rajagopal, S., Venugopalan, V. P., Van der Velde, G. & Jenner, H. A. Greening of the coasts: A review of the Perna viridis success story. Aquat. Ecol. 40, 273–297 (2006).

Power, A. J., Walker, R. L., Payne, K. & Hurley, D. First occurrence of the nonindigenous green mussel, Perna viridis in coastal Georgia, United States. J. Shellfish Res. 23, 741–744 (2004).

Baker, P. et al. Range and dispersal of a tropical marine invader, the Asian green mussel, Perna viridis, in subtropical waters of the southeastern United States. J. Shellfish Res. 26, 345–355 (2007).

Dias, P. J. et al. Genetic diversity of a hitchhiker and prized food source in the Anthropocene: The Asian green mussel Perna viridis (Mollusca, Mytilidae). Biol. Invas. 20, 1749–1770 (2018).

Galimany, E., Lunt, J., Domingos, A. & Paul, V. J. Feeding behavior of the native mussel Ischadium recurvum and the invasive mussels Mytella charruana and Perna viridis in FL, USA, across a salinity gradient. Estuar. Coast. 41, 2378–2388 (2018).

de Messano, L. V. R., Goncalves, J. E. A, Messano, H. F., Campos, S. H. C. & Coutinho, R. First report of the Asian green mussel Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: A new record for the southern Atlantic Ocean. Bioinv. Rec. 8, 653–660 (2019).

Hawkins, A. J. S., Smith, R. F. M., Tan, S. H. & Yasin, Z. B. uspension-feeding behaviour in tropical bivalve molluscs: Perna viridis, Crassostrea belcheri, Crassostrea iradelei, Saccostrea cucculata and Pinctada margarifera. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 166, 173–185 (1998).

Monirith, I. et al. Asia-Pacific mussel watch: Monitoring contamination of persistent organochlorine compounds in coastal waters of Asian countries. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 46, 281–300 (2003).

Ramu, K. et al. Asian mussel watch program: Contamination status of polyhrominated diphenyl ethers and organochlorines in coastal waters of Asian countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 41, 4580–4586 (2007).

Qu, X. Y., Su, L., Li, H. X., Liang, M. Z. & Shi, H. H. Assessing the relationship between the abundance and properties of microplastics in water and in mussels. Sci. Total Environ. 621, 679–686 (2018).

Naidu, S. A. Preliminary study and first evidence of presence of microplastics and colorants in green mussel, Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758), from southeast coast of India. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 140, 416–422 (2019).

Zhang, X. et al. High-throughput identification of heavy metal binding proteins from the byssus of Chinese green mussel (Perna viridis) by combination of transcriptome and proteome sequencing. PLoS ONE 14, e0216605 (2019).

Guerette, P. A. et al. Accelerating the design of biomimetic materials by integrating RNA-seq with proteomics and materials science. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 908–915 (2013).

Vurture, G. W. et al. GenomeScope: Fast reference-free genome profiling from short reads. Bioinformatics 33, 2202–2204 (2017).

Gerdol, M. et al. Massive gene presence-absence variation shapes an open pan-genome in the Mediterranean mussel. Genome Biol. 21, 275 (2020).

Sun, J. et al. Adaptation to deep-sea chemosynthetic environments as revealed by mussel genomes. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0121 (2017).

Uliano-Silva, M. et al. A hybrid-hierarchical genome assembly strategy to sequence the invasive golden mussel Limnoperna fortunei. Gigascience 7, 1–10 (2018).

Li, R. et al. The whole-genome sequencing and hybrid assembly of Mytilus coruscus. Front. Genet. 11, 440 (2020).

Yoshiyasu, H., Ueda, I. & Asahina, K. Annual reproductive cycle of the green mussel Perna viridis (L.) at Enoshima Island, Sagami Bay, Japan. Sessile Organisms 21, 19–26 (2004) (in Japanese with English abstract).

Wang, S. et al. Scallop genome provides insights into evolution of bilaterian karyotype and development. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0120 (2017).

Zhang, G. et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature 490, 49–54 (2012).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: Assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

Vinther, J. The origin of molluscs. Palaeontology 58, 19–34 (2015).

Allcock, A. L., Lindgren, A. & Strugnell, J. M. The contribution of molecular data to our understanding of cephalopod evolution and systematics: A review. J. Nat. Hist. 49, 1373–1421 (2015).

Wanninger, A. & Wollesen, T. The evolution of molluscs. Biol. Rev. 94, 102–115 (2019).

Wood, A. R., Apte, S., MacAvoy, E. S. & Gardner, J. P. A. A molecular phylogeny of the marine mussel genus Perna (Bivalvia: Mytilidae) based on nuclear (ITS1&2) and mitochondrial (COI) DNA sequences. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 44, 685–698 (2007).

Guo, Z., Han, L., Liang, Z. & Hou, X. Comparative analysis of the ribosomal DNA repeat unit (rDNA) of Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) and Perna canaliculus (Gmelin, 1791). Peer J., e7644 (2019).

Inoue, K. et al. Cloning, sequencing and sites of expression of genes for the hydroxyarginine-containing adhesive-plaque protein of the mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. Eur. J. Biochem. 239, 172–176 (1996).

Waite, J. H. Formation of the mussel byssus: Anatomy of a natural manufacturing process. In Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation, vol. 19, Biopolymers (ed. S.T. Case), pp. 27–54. Springer (1992).

Inoue, K., Takeuchi, Y., Miki, D. & Odo, S. Mussel adhesive plaque matrixprotein gene is a novel member of epidermal growth factor-like gene family. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 6698–6701 (1995).

Miki, D., Takeuchi, Y., Inoue, K. & Odo, S. Expression sites of two byssal protein genes of Mytilus galloprovincialis. Biol. Bull. 190, 213–217 (1996).

Qin, X. X., Coyne, K. J. & Waite, J. H. Tough tendons—Mussel byssus has collagen with silk-like domains. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 32623–32627 (1997).

DeMartini, D. G. et al. A cohort of new adhesive proteins identified from transcriptomic analysis of mussel foot glands. J. R. Soc. Interface 14, 20170151 (2017).

Qin, C. et al. In-depth proteomic analysis of the byssus from marine mussel Mytilus coruscus. J. Proteomics 144, 87–98 (2016).

Koide, T. & Nagata, K. Collagen biosynthesis. Top. Curr. Chem. 247, 85–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/b103820 (2005).

Gorres, K. L. & Raines, R. T. Prolyl 4-hydroxylase. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 45, 106–124 (2010).

Vasta, G. R. et al. Biochemical characterization of oyster and clam galectins: Selective recognition of carbohydrate ligands on host hemocytes and Perkinsus parasites. Front. Chem. 8, 98 (2020).

Ohkawa, K., Nishida, A., Yamamoto, H. & Waite, J. H. A glycosylated byssal precursor protein from the green mussel Perna viridis with modified Dopa side-chains. Biofouling 20, 101–115 (2004).

Anderson, K. E. & Waite, J. H. Biochemical characterization of a byssal protein from Dreissena bugensis (Andrusov). Biofouling 18, 37–45 (2002).

Suhre, M., Gertz, M., Steegborn, C. & Scheibel, T. Structural and functional features of a collagen-binding matrix protein from the mussel byssus. Nat. Commun. 5, 3392 (2014).

Yoo, H. et al. Sugary interfaces mitigate contact damage where stiff meets soft. Nat. Commun. 7, 11923 (2016).

Yu, J. et al. Mussel protein adhesion depends on interprotein thiol-mediated redox modulation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 7, 588–590 (2011).

Kajitani, R. et al. Efficient de novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes from whole-genome shotgun short reads. Genome Res. 24, 1384–1395 (2014).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Schulz, M. H., Zerbino, D. R., Vingron, M. & Birney, E. Oases: Robust de novo RNA-seq assembly across the dynamic range of expression levels. Bioinformatics 28, 1086–1092 (2012).

Wu, T. D. & Watanabe, C. K. GMAP: A genomic mapping and alignment program for mRNA and EST sequences. Bioinformatics 21, 1859–1875 (2005).

Kim, D., Paggi, J. M., Park, C., Bennett, C. & Salzberg, S. L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 907–915 (2019).

Pertea, M., Kim, D., Pertea, G. M., Leek, J. T. & Salzberg, S. L. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1650–1667 (2016).

Simakov, O. et al. Insights into bilaterian evolution from three spiralian genomes. Nature 493, 526–531 (2013).

Murgarella, M. et al. A first insight into the genome of the filter-feeder mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis. PLoS ONE 11, e0151561 (2016).

Gotoh, O. Direct mapping and alignment of protein sequences onto genomic sequence. Bioinformatics 24, 2438–2444 (2008).

Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics Suppl 2, ii215–225 (2003).

Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinform. 5, 59 (2004).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 10, 421 (2009).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12 (2011).

Patro, R., Duggal, G., Love, M. I., Irizarry, R. A. & Kingsford, C. Salmon provides fast and bias-aware quantification of transcript expression. Nat. Methods 14, 417–419 (2017).

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 511–515 (2010).

Haas, B. J. et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 8, 1494 (2013).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: Solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 16, 157 (2015).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. I. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: A novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nuc. Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014).

Lechner, M. et al. Proteinortho: Detection of (Co-)orthologs in large-scale analysis. BMC Bioinform. 12, 124 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H06279 (PAGS) and 18H02261, and by ‘The University of Tokyo FSI – Nippon Foundation Research Project on Marine Plastics’.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This study was conceived by K.I. Mussel samples were collected by I.U., M.S., A.K., and Y.Y. DNA and RNA were purified by M.S., A.K., and Y.Y. Genome sequencing was performed by A.T., assembled and analyzed by T.I. and H.T., and annotated by Y.Y. and C.S. Molecular phylogenetic analyses were carried out by H.T. and Y.Y. The manuscript was prepared by K.I. with input from other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Inoue, K., Yoshioka, Y., Tanaka, H. et al. Genomics and transcriptomics of the green mussel explain the durability of its byssus. Sci Rep 11, 5992 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84948-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-84948-6

This article is cited by

-

Divalent metal transporter-related protein restricts animals to marine habitats

Communications Biology (2021)

-

Mussel biology: from the byssus to ecology and physiology, including microplastic ingestion and deep-sea adaptations

Fisheries Science (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.